By Joseph S. Covais

On September 17, 1944, a massive but hastily planned airborne invasion of the Netherlands was launched. Codenamed Market-Garden, the operation called for three Allied airborne divisions (British 1st and American 82nd and 101st) to land along a narrow corridor reaching from advanced positions along the Dutch-Belgian border to a bridgehead on the northern bank of the Rhine River at Arnhem.

It was a bold move and would yield tremendous results as long as everything unfolded just right. But Arnhem was about 70 miles behind German lines, and that was farther into enemy-occupied territory than any large-scale airborne drop that had been attempted up to that time. Nonetheless, as it was conceived by British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery, the plan could immediately place American and British forces within striking distance of the German industrial heartland.

As the world now knows, things did not go as planned. Unbeknownst to the Allied command, two rehabilitated SS divisions, along with a strong contingent of German paratroopers, were coincidently in the vicinity, refitting close to the Allied drop zones, making resistance was far greater than the operation’s planners were expecting.

Moreover, the British armored column that was tasked with racing through the two American airborne divisions to join the British paratroopers at Arnhem proceeded cautiously, fell far behind schedule, and left its countrymen beleaguered on the north bank of the Rhine.

By the morning of September 25, time had run out for the besieged British 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem. With their armored column lingering miles away in the vicinity of the Nijmegen Bridge, on the northern bank of the Waal River, the British paratroopers had been cut off from the rest of the MarketGarden operation for over a week.

Outnumbered and with their supplies exhausted, the survivors had little choice but to begin surrendering, although small groups attempted to slip through the encircling Germans. Some very few were successful, but the British 1st Airborne Division and the attached Polish Brigade ceased to exist as a fighting force. With their demise went the entire reasoning behind Montgomery’s Market-Garden plan.

From this point forward, all pretense of a sudden movement that would quickly end the war came to a close, and the efforts of the invasion would henceforth be conducted on a broad front.

The 319th Glider Field Artillery

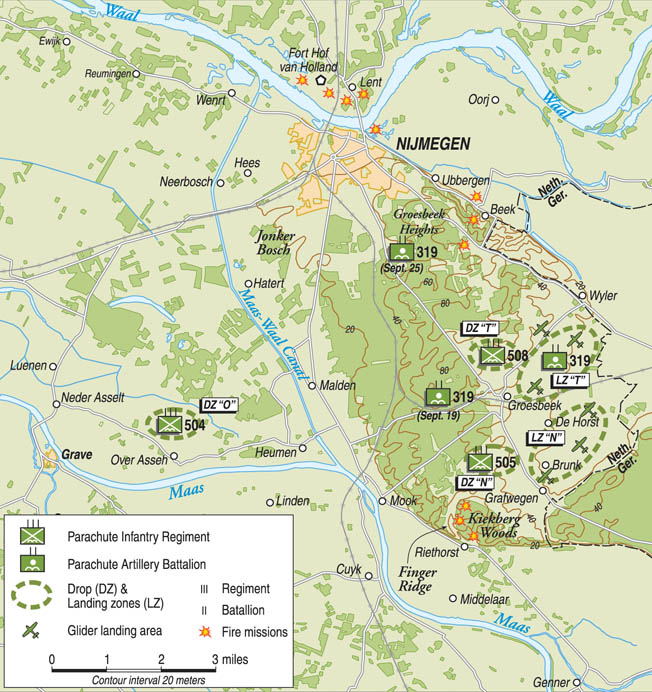

On the afternoon of September 24, the 82nd Airborne Division was redeployed to accommodate its newly arrived 325th Glider Infantry Regiment. Infantry units that had seen the heaviest fighting were placed in reserve but, as any artilleryman knows, those who serve the guns are never really relieved. The 319th Glider Field Artillery was among them. It was ordered to take up new positions farther south, closer to the town of Mook, where it would support the 325th.

The 319th had been part of the 82nd since day one. It was a veteran outfit—arguably the most experienced of all the division’s artillery battalions, having already seen extensive action in Italy and Normandy. On the afternoon of September 18, the unit landed by glider northeast of Groesbeek and within 90 minutes was hammering German positions with its 75mm pack howitzers.

For the first few days it was a touch and go situation. Encircled as the division was, the 319th found itself firing continuously in every direction. “We were firing 3200 mills. That’s a circle!” is how one sergeant in the battalion’s A Battery later put it.

The unit was part of the 508th Regimental Combat Team, with instructions to supply close-in artillery support to that regiment in all its operations. This it did admirably as fighting surged back and forth for the city of Nijmegen, as well as the villages of Beek, Wyler, and the Groesbeek Heights.

Two Captains of the 319th

The 319th was organized as two firing batteries: “A” or Able and “B” or Baker, together with a headquarters battery. Able was under the command of Captain C. Lenton “Charlie” Sartain, a native of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and 1942 graduate of LSU. Having just turned 24 on the day after the battalion landed in Holland, Sartain had risen from an ROTC 2nd lieutenant to command of one of the premier batteries in the division’s field artillery since joining the battalion two years before. He was an energetic and charismatic officer who, despite his gentle southern Louisiana style, did not suffer fools.

Sartain had earned a reputation with his superiors as enterprising, if sometimes unmindful of their authority. Meanwhile, enlisted men in the battalion knew him as an officer who never cut into a chow line or flaunted his rank. With his law school background, Sartain was also recognized as a guardhouse lawyer who had rescued numerous enlisted men from the legal consequences of GI high-jinx.

As the 319th’s batteries set up their new gun positions along the railroad tracks west of Groesbeek, the previous day’s rain eased off but left behind a thick carpet of clouds. The weather was now sharply cooler; everyone felt the first real taste of autumn. Activity overhead was lively despite the gray skies, and the cannoneers were enthusiastic spectators of dogfights between German and British fighters.

Those in the battalion who were veterans of Italy and Normandy remarked that the German air presence was stronger here in Holland than in the previous campaigns, no doubt because they were now closing in on the enemy’s homeland air bases.

While the gun crews finished digging their emplacements and stretching camouflage netting over their 75s, orders were issued confirming new liaison and forward observer assignments with the 325th.

Word was also received at battalion headquarters that the 319th had been awarded a second Presidential Unit Citation; their first PUC was earned while fighting alongside Darby’s Rangers in Italy. This time the decoration was in recognition of the role the unit played in the battle for Normandy. The award of any Presidential Unit Citation was, of course, a real distinction, but to be given this honor twice was exceptional.

Now, on the afternoon of September 25, satisfied that his battery was well established in its new position, Sartain decided to make his customary visit to each of his forward observers while there was still daylight. Just as he told his driver, Corporal Louis Sosa, to get the jeep, the battery telephone rang. It was Captain John R. Manning, the battalion’s assistant S-3 (operations officer) calling Sartain from battalion HQ and asking if he could go along on Sartain’s usual daily rounds of the observation posts. Sartain said fine.

A few years older than Sartain, Manning was another ROTC product. Tall and muscular, the soft-spoken Manning came from New York’s Hudson River Valley and was recognized throughout the battalion by the British Naval duffel coat he had acquired in Italy. By the time of Operation Market-Garden, he was serving as the Assistant S-3 of the 319th.

Sartain and Manning had a long history together in the 319th stretching all the way back to Fort Bragg. In June 1943, when a temporary third “Charlie” Battery was formed from men whom Sartain remembered as “oddballs,” Manning was placed in command, with Sartain as his executive officer. With a working relationship that was a perfect complement to each other’s command style, and with a combination of respect for the men and high expectations, the two molded “C” into the best battery in the battalion.

Afterward, once the battalion was sent to England to prepare for the invasion of France, the 319th reverted to two firing batteries. Able Battery was given to the Manning/Sartain command team. Just as they had done with “C,” the duo polished A Battery into a high-morale, high-efficiency outfit where things got done without busting the men’s chops unnecessarily.

On the night of June 6, 1944, however, Manning had been badly injured in the glider landings. He was evacuated off Utah Beach and command of A Battery went to Sartain. Once the outfit returned to England the arrangement was made permanent. “I really thought Johnny would come back to the battery, but they wanted him up at Battalion Headquarters, so I stayed with the battery,” Sartain later explained.

On September 24, the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, with which the 319th’s forward observers were now placed, had taken over the positions formerly occupied by the 505th PIR. Their line was an irregular semicircle defending the approaches to Mook and Groesbeek. This arc extended from the Maas-Waal Canal, west of Mook, to the Groesbeek Heights, facing due east toward the Reichswald. Between the two flanks was the regiment’s 2nd Battalion, southeast of Mook and squared off against German positions in another thickly forested cluster of hills known as the Kiekberg Woods.

Louis Sosa, Sartain’s driver, was a Tampa Cuban who became Captain Manning’s driver in Italy during the old C Battery days. Now that Manning was up at Battalion HQ, he drove for Sartain. Sosa first took the two captains out to a point near the observation post occupied by Lieutenant Bob McArthur. As was routine, he parked the jeep in a protected spot and stayed with it while Sartain and Manning went the rest of the way on foot.

“Things were quiet, there was nothing going on,” recalled Sartain of that day. “It looked like it was going to be a quiet afternoon.” McArthur’s position was on a promontory south of Mook. From this vantage point, McArthur indicated the known German positions while Sartain looked through his field glasses. At an outpost near those trees was a suspected machine gun in the rubble of a building; Manning marked them on his corresponding map overlay. Everything was in order and, for Sartain especially, it was good to see his old chief of sections now serving as a very competent commissioned officer. When they were finished, Sartain ended the conference saying to him, “You’re doing a great job, tiger. Carry on!”

Back at the jeep, Sosa drove them to the next destination. They were on the road to Mook when he told the captains that he had something that might interest them. Sosa tapped on a German grenade box wedged between the seats and in which he was known to keep valuables. When Manning lifted the lid, his face lit up. There were several hens’ eggs inside, offering a welcome break from Army chow. Sosa pulled off the road and found a discreet place to park the jeep. He heated a Bunson burner he had with him, fried the eggs, and made some coffee for the three of them.

Finger Ridge Under Fire

Refreshed, it was now time to check on the other forward observers (FO) with the 325th’s 2nd Battalion. Part of this battalion’s line included a position known as Finger Ridge. This piece of high ground followed a “U” or horseshoe shape. One arm of the horseshoe protruded some distance toward the German positions within the Kiekberg Woods to the northeast. It ran alongside the main highway leading to Mook from enemy-held territory along the German border and also commanded the large expanse of open ground to its east and south.

This open terrain extended all the way to the Maas River, and at the point opposite Finger Ridge that distance was not great, creating, in effect, a choke point for any movement up or down the highway from Mook. Finger Ridge was consequently of some strategic importance to both the Americans and Germans in any attack or defense in the area.

Though mostly covered in pine forest, and affording an excellent view of any approaching forces, the ridge was still an exposed location, vulnerable to attack from three sides. Lieutenant Fellman’s FO team was located on the ridge with a platoon of E Company of the 325th Glider Infantry, and it was there that Manning and Sartain chose to make their next inspection.

Sosa drove up a dirt lane that led up the eastern side of Finger Ridge. It wouldn’t be safe to proceed farther, as they would be visible to Germans in the Kiekberg. Instead, Sosa parked the jeep out of sight behind some trees and said he’d wait for the officers to return.

Even as they were getting out of the jeep, the sound of machine-gun and artillery fire was erupting from over the ridge. “Just before Manning and I got there we heard all the racket, all this commotion, so we rushed up there,” remembered Sartain. The two captains came running into the position, bent over low to present a smaller target. Twenty-millimeter rounds were blasting through the trees above and machine- gun fire was snipping through the air all around. Interspersed among the trees were foxholes and slit trenches.

The captains jumped into one of the first holes they reached and demanded to know where the officer in charge was. The soldier just shook his head. He was young and very frightened. What about the FO team, did he know where they were? Again, the man couldn’t help them.

They got up and kept going. In another foxhole a man pointed and told them, “I think your people are over there.” Then realizing he was speaking to two officers, added, “Sir, do you know where our CO is?” Sartain and Manning exchanged glances. They noticed that none of these men were returning fire. Instead, they all seemed to be huddled at the bottom of their slit trenches, paralyzed. Manning next got up and bounded to the adjoining foxhole, then repeated the process. Sartain followed.

Farther up they noted a telephone line and guessed that it might at least guide them to their forward observer. It did. Sartain and Manning tumbled into a slit trench on the edge of the tree line. Placed at a bend in the ridge, this hole was a little larger than the others. In it was Lieutenant Fellman with his radio operator. Sartain immediately wanted to know who was in charge of this position; Fellman didn’t know. Besides himself, he said, there hadn’t been an officer up here since he arrived the night before.

Sartain looked his lieutenant square in the face. Fellman still had a nasty, albeit scabbed-over, gash running forehead to chin from the glider landing the week before. “Well, somebody’s running this shooting match; who the hell is it?” was Sartain’s repeated question.

“Captain, nobody seems to be in charge up here,” was all Fellman could tell him. Fellman then started explaining that there had been more and more German presence throughout the day, that the infantry in the foxholes were uneasy, under increasing sniper and machine-gun fire, and for the last hour or so they had heard the sound of tanks.

Pointing skyward to the 20mm rounds passing overhead, Fellman’s radio operator added, “Now these Heinie bastards are throwing this shit at us, too!” When Manning picked up the telephone receiver it was obvious the line had been broken. “God damn it,” he said. “Get Fire Direction on that radio right now!”

Sartain took off to assess the situation and hopefully find someone responsible for this position. Jumping from hole to hole, he found the infantrymen confused and without leadership.

“There was no NCO with them, there was no officer with them, and they were hunkered down in their foxholes,” he recalled. “This surprised the hell out of me. I would say there was probably a full platoon or more. But they didn’t know boot turkey. I mean, this had to have been the first time those kids had ever heard a shot fired over them. Had to be, because they really did not know what to do, there being no NCO or lieutenant, platoon commander, or anybody with them. Wasn’t anybody there! That’s what I never could believe and nobody ever explained it to me.”

The 319th Retaliates With Artillery

When Sartain returned to the observation post, Manning was on the radio in a deep huddle with Fire Direction. He closed out the communication, turned to Sartain, and assessed the situation.

Sartain reported that there were about 50 infantrymen holding this position—a platoon from E Company—but they had no mortars, no light machine guns, no bazookas, or any other weapons heavier than a BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle). There was, moreover, no apparent commanding officer. “Johnny,” Sartain said, “these kids are scared.”

“All right,” Manning answered, “let’s give them a pep talk, get a few of the corporals together, and get them settled down. There’s got to be a few corporals at least that we can talk to.”

Sartain shook his head. “I don’t think so, John. And besides, these boys up here don’t know what they’re doing. They’re pretty shook up, and if hell breaks loose, there’s no telling what they’ll do.”

Manning thought for a moment, then agreed that they couldn’t risk leaving. He told Sartain, “I want you to get a defense going. I’ll get us supporting fire from the battalion.”

In a flash, Sartain was gone. By this time it was clear that an outright attack on the position was on the way. Several enemy light and heavy machine guns continuously peppered the Americans in their foxholes, kicking up dust all over the place. Germans could be seen rising up from the tall grass to spring forward or get a clear shot at the GIs on the hill, then they’d disappear again to crawl closer.

in Western Europe.

Describing what happened, Sartain said, “Manning took over the radio and I took over reorganizing them. All this time I was jumping from one group to another. I kicked a few kids in the butt and then we were ready for them.”

At first the GIs were slow to respond. The absence of their own leadership had left them having to shake off a strange torpor. “They were not seasoned airborne troopers,” said Sartain. “You could just tell. They were frightened, you know? But you keep going among them and give them a little spirit and then they start responding. We started returning small-arms fire and the troops started to act like troopers. But I was lucky that I had been with the infantry enough to really know what to do.”

For the platoon on the ridge, the welcome sound of artillery came screaming overhead. They all knew this was their own supporting fire, and that knowledge raised their spirits immensely. Explosions now erupted all over the plain across which the Germans were advancing. Given the volume of fire, the shells had to be coming from not only the 75s of the 319th Glider Field Artillery, but the 105s of the 320th as well. Licking their wounds, the Germans retreated into the grasslands they had attacked from, probably all the way to the banks of the Maas.

The respite gave Sartain a chance to better consolidate the defense. “First thing I observed,” he said, “there were no outposts. Now that’s basic infantry tactics, basic common sense. You get your outposts out so no one can sneak up on you. So I got two guys to go down the damn hill and set up an outpost so we could figure out what in the hell was going on down there.”

Nor did Manning lose time taking advantage of the lull. It was obvious to him that infantry couldn’t hold The Finger alone. Had it not been for the artillery barrage, the position might have been overrun during that first attack, and there were bound to be more. Of course, accuracy and speed of response would be key.

First he dispatched Fellman’s radio operator and another man to repair the break in the telephone line. With Fellman filling in, Manning next had himself put in direct communication with the 319th’s batteries.

Looking back, Sartain explained why, saying, “Once all the noise and everything else cleared, Manning systematically picked out and zeroed in on various concentration points. He had concentration points throughout the area. All he’d have to do is call Concentration Two, or Concentration Four, Concentration Eleven. Manning took the radio from Fellman and really took over the artillery, and I’m delighted because Manning had a lot more savvy about artillery fire. Fellman was over in the foxhole with Manning, but Fellman was brand new.”

“It All Went Over Our heads”

There hardly had been time to register the battalion’s guns when the fusillade of 20mm cannon fire resumed, this time accompanied by the unmistakable growl of armored vehicles. Looking out across the open plain, Sartain, Manning, Fellman, and all the other GIs on Finger Ridge could see armored tracked vehicles advancing toward them.

At this distance, under the confusion of battle, it was difficult to identify just what variety of German armor they were watching. Enemy soldiers in greater numbers than had attacked before could also be seen riding on and clustered behind the advancing armor.

The GIs readied themselves by placing grenades along the tops of their slit trenches and filling their pockets with clips of ammunition. They started firing, more to feel like they were fighting back, since even well-aimed shots would have to be very lucky to hit a target at that range.

Still, the armored attack pressed closer. One vehicle would stop momentarily to lay down a withering fire from its 20mm cannon, while the other would roll on toward the American position. Sartain went dashing from foxhole to foxhole, heartening the men to hold their ground. At first he scrambled along on all fours, but then realized this was an unnecessary precaution because, oddly, all the heavier 20mm fire was passing overhead.

As Sartain put it, “These 20mm guns just kept shooting up the trees above us. I guess they couldn’t depress their guns enough, but it all went over our heads. Everything they shot at us went over our heads, and there was an awful lot of it. It made a big roar, but once I was satisfied that they could not lower their guns in front of us, then I was safe in running back and forth.”

By now supporting fire from the American artillery batteries was falling. There were air bursts, high explosives, and phosphorous shells going off in quick succession. No direct hits were scored, however, and the German infantry was getting closer.

“The grass was between knee and waist high,” said Sartain. “They would drop down and you couldn’t see them. Sometimes we’d see a German head pop up in the grass and the whole outfit would start firing. Or then they’d give an order and jump up and all come at us. When they were close enough, then our infantry with their rifles could take care of them.”

At one foxhole Sartain came across a soldier paralyzed with fear. The man was holding out his M-1 rifle to the captain. He had a panicked look in his eyes and kept saying, “It’s stuck, it’s stuck. It’s jammed!” Instinctively Sartain knew he had to restore the man’s initiative and belief that he could help himself.

“Well,” he told him, “you know how to break it down. Clean the son of a bitch! Clean it, clean it!” Sartain went onto the next foxhole, but made a mental note that he’d need to check back with this man. “Well, after a while I passed him again. He’d broken it down and cleaned it. He was firing and he was so proud of himself.”

As aggressive as this second reinforced German attack was, Manning’s astute preparation allowed him to pinpoint fire on the approaching armor with unusual speed and accuracy. Armor that had stopped to fire and even moving targets were showered with explosives. There was no time lost since the exact elevation and deflection of the battalion’s guns on so many points had already been registered back at fire direction.

Moreover, Manning ordered that phosphorous shells be used. Sartain later explained why this type of round was most effective. “We had the phosphorus shells to strip the German troops from the tanks,” he said. “When it went off, it scattered that hot phosphorus all over the countryside in itty bitty pieces, and it was just flaming hot. If a speck of that white phosphorous got on you, it’d burn through your clothes and everything else. It burned, man, it really burned!

“Manning had already established the coordinates with single gun registrations, so then the battery would just shoot on them and the battery really came through. When the infantry people took off or were eliminated, those tanks would turn around and leave because they had no protection. No, I don’t think the tanks were knocked out, but once they stripped the infantry support from around the tanks, then they took off and left.”

Flammenwerfer Assault

The German attack was now repulsed, but there was every reason to believe they would be back for another try. Sartain looked out over the open plain. There was a thin haze of smoke from the phosphorous and explosives. Dead and wounded Germans were scattered through the trampled, charred, and ground-up grassland, many of them horribly burned and screaming in pain. After a few minutes, white flags appeared, followed by litter bearers picking up these unfortunate souls and taking them away for medical treatment.

Sartain took the opportunity to make his way back to the OP to commiserate with Manning. He advised him that ammunition would become a problem if these attacks went on much longer. Manning made due note and assured Sartain that he would renew his efforts to establish either radio or telephone contact with the 325th, along with continuing to build up his repertoire of registered concentration points.

By now the telephone line was fixed. That made communication with both the 319th and the 320th more secure, but they needed to get communications going with the 325th, too. It was still a mystery to them why no one from this regiment had appeared at the position, either alone or with reinforcements.

The conference between Manning and Sartain had not gone on long when the rumble of tracked armored vehicles started to rise out of the distance. Someone shouted out, “Hey, here they come again!” When they heard this, the captains hurriedly concluded their meeting. Sartain set off for the infantry’s foxholes, while Manning was already cranking up the artillery support.

The E Company platoon had beaten back two attacks by now. They had confidence that they could face down another, but when they began opening fire, the Germans replied with a weapon that engendered fear in even the bravest of men. It was the flamethrower.

The German Flammenwerfer was, according to an early 1944 U.S. Army intelligence bulletin, a weapon normally used against enclosed fixed positions such as pillboxes, or for its shock value when placed with storming columns. Operated by combat engineers or Pionieren, the Germans were in the habit of assigning pairs of flamethrowers to infantry companies when the situation was appropriate. The apparatus consisted of two concentric rings filled with compressed nitrogen as its burning agent.

Worn on the operator’s back, the containers held about one and a half gallons of fuel. The nitrogen was sent through wire-wrapped tubing to a hand-held nozzle about 18 inches long, fitted with a valve and ignition trigger. Earlier versions of the Flammenwerfer utilized a battery-started hydrogen flame to ignite the nitrogen, but by this point in the war most German flamethrowers used a blank rifle cartridge to set off the nitrogen agent.

When filled with burning agent, the entire weapon weighed 47 pounds and was capable of throwing its flame about 25 yards. This was not, in fact, very far. Consequently, the engineer troops who operated flamethrowers relied on being able to approach their target under cover of supporting machine guns or tanks before letting loose with their flame. In addition, once flame was discharged the exact location of the man operating the apparatus was invariably disclosed, making casualties among flamethrowing engineers inordinately high.

There was, though, another way of employing the Flammenwerfer that did not require that the operator be placed in such close proximity to the enemy. This was the flamethrower as an agent of terror. Even the U.S. Intelligence Bulletin described the effect of the flamethrower as “chiefly psychological.” The prospect of being roasted alive was simply more than most men could endure, and crews of any flame unit depended on this fact to a large extent.

The German armor was still some distance out when the Flammenwerfer crews announced their presence on the field with short bursts of flame, evidently playing on the psychological impact of their weapon.

Indeed, at least one German flamethrower had already been reported by members of E Company around dawn that day when an enemy raiding party stormed through a portion of the Finger Ridge positions. It is possible that some of the men on The Finger with Sartain and Manning could have had a brush with it at that time. At very least it is safe to assume that rumors of flamethrowers had already circulated among them and contributed to their uneasiness.

Whether or not the two men whom Sartain placed in a forward outpost had heard rumors about Germans in the vicinity with this weapon, they came bounding up the hill immediately when the first signs of flamethrowers appeared. “They really hustled their asses up to us,” Sartain remembered. As the two threw themselves into the first foxholes they reached on the ridge, Sartain jumped up to meet them. “Get your asses back down there,” he ordered. “No one told you to abandon your post!”

Sartain understood their fear, but he also knew that fear was a very contagious disease. “I was kind of upset about it because, unless they got personally attacked, they had no business leaving their outpost. I fussed at them and sent them back down the hill.” When Sartain next looked across the field it was clear the panzers were getting rapidly closer, bringing with them infantry spitting jets of flame. Immolation would be a horrible way to die and Sartain thought: “If they ever get close enough, that’s gonna be our ass.”

Meanwhile, back at A Battery’s gun position, a radio call came in directly from Captain Manning. Lieutenant Marvin Ragland was the battery’s executive officer, and he remembered the call: “He called in and said, ‘There’s a counterattack coming. I want you to fire in this area, and I want you to keep firing until we tell you to stop.’ So, I don’t know how long we fired, but we had a lot of ammunition and, man, those guns were getting pretty hot.”

Although the air and ground across which the Germans were advancing was filled with exploding ordnance of all kinds, as well as small-arms fire from E Company, the enemy was determined to take Finger Ridge and kept pressing forward. Aware that they were holding an advanced point, Sartain grew concerned that the Germans would try to encircle the position. Periodically he would scramble up to the crest to take a look behind the ridge for signs this was happening but never did see any attempt at encirclement.

Calling In Close Artillery Support

Now the events on Finger Ridge were generating attention from other artillery battalions, and a Piper Cub from one of them made air observations. Considerable supporting fire beyond the 319th was brought in. “Oh yeah, there could have been a lot of it,” Sartain commented. “They brought in some heavy artillery. I know we had some 155s that were attached to the division. There could have been contributing fire from the 320th because that was a large area out in front of us. Manning would call, ‘Fire for effect,’ and they would just clobber the area, but that was farther out.”

As the Germans closed in, a furious battle boiled up involving artillery, machine guns, armored vehicles, 20mm cannon, flamethrowers, and any number of small arms. Dug in as they were, the GIs were protected and inflicting terrible casualties on the Germans now that they had them well within rifle range. Until that point, artillery took its toll on the enemy the whole way.

“There was only one tank that got anywhere close to us,” said Sartain. “Then the flamethrowers were right behind him and it was only one flamethrower that got within distance to do us any damage. If it’d gotten any closer he could have hit us, but he was about 40 yards away and we were just out of his range.”

Continuing his account, Sartain said, “Manning brought the artillery to within 75 yards of us, but he only registered one gun and only brought one gun in real close. See, he didn’t want to worry about all six of them shooting. We didn’t want the whole battery in on it, no, no. One shot. Then, when the targets were out farther, we used the whole battery. And they would bring in B Battery also. But on real close-in shots, we registered with one gun.”

Calling in concentrations at such a close proximity necessarily required an extraordinary degree of coordination and skill. In a memoir written by Manning about 50 years after the event, he described how he was able to pinpoint artillery fire so that it would land just beyond the foxholes on Finger Ridge. “It got down to me talking directly to Battery B, under Captain Hawkins, and his Section Chief, Sergeant Delos Richardson, who had been my first sergeant in Battery C,” Manning wrote.

“Del and I coordinated things down to the last mil of elevation and the last yard of distance. We were able to drop the artillery rounds on the attackers within 25 or 30 yards of where we sat. We blew up two flamethrowers, a few tanks, and caused a good amount of damage and confusion. Finally got things cooled off. Evidently the Germans were impressed enough to take their attack somewhere else.”

When compared, some inconsistencies emerge between Manning’s written account and Sartain’s memory that deserve to be examined. That Manning would have insisted the closer concentrations be fired by the batteries of the 319th is both plausible and to be expected. After all, the battalion was as accustomed to Manning’s manner of adjusting fire as he was with their response to his directions. The gunners of the 319th would naturally have had his trust more than those of any other unit.

Also, given the gun positions of the 319th and 320th relative to Finger Ridge, Sartain’s statement that, “The shells came over from right to left, not from behind us. That’s why Manning was able to get them in so close,” also supports the idea that it was the 319th that conducted the close fire.

Both agree that one gun was used when the panzers and flamethrowers were at their closest. But Sartain also maintained that when single-gun fire was called for, it came from A Battery, saying, “Manning wanted only one gun, and he wanted that gun from A Battery. It was brought in so close that I’m positive Manning didn’t want anybody else but A Battery shooting those damn shells.”

Battalion records indicate that B Battery fired considerably more rounds than A Battery during the period of the Finger Ridge attacks—627 for B compared with 386 rounds fired by A. Unquestionably, B Battery was more active, but these numbers could be interpreted as supporting the idea that only one gun of A Battery was firing during selected periods of time.

Manning, however, was very specific in his account about personally arranging this fire with Sergeant Delos Richardson. When one considers that Manning’s greatest experience working one on one with any firing battery’s chief of sections took place during the tricky fire missions in Italy at Chiunzi Pass with Sergeant Richardson, then of C Battery, it is understandable that he would have sought this same section chief on that day in Holland.

Whether the Germans were sending tanks in the sense of vehicles with enclosed turrets fitted with a high-velocity cannon against the Finger Ridge position is ambiguous, even though Manning used the term “tanks” in his memoir and 319th Battalion records also describe the vehicles as tanks. Yet, Sartain did not recall, nor Manning mention, any direct cannon fire such as one would expect from attacking panzers.

In this area of Holland the Germans were generously equipped with half-tracks on which 20mm antiaircraft guns were carried, and they were in the habit of using them on both air and ground targets. Given the volume of 20mm fire directed against Finger Ridge and the absence of direct cannon fire, it is most likely that at least some, if not all, of the enemy armor was comprised of half-tracks mounted with these guns.

Low on Ammunition, High on Adrenaline

With all this array of firepower directed against them, it appeared to the men on Finger Ridge that they were fighting alone. In fact, the American command structure in the Mook area was aware that the position was under attack. Possibly Manning was able to get through to the 325th’s 2nd Battalion HQ, or other members of E Company elsewhere on the ridge may have reported what was happening.

However it occurred, beginning at about 6:00 pm, 325th HQ acknowledged that a full-scale assault was under way. The flank of C Company, the next unit to E Company’s west, was described in that unit’s combat journal as “threatened.” Men of E Company who were posted at other points along the extended Finger Ridge also recorded being attacked that day. All this suggests that the attack on Sartain and Manning’s position was not an isolated one, but rather part of a larger offensive operation, and that the Germans were having some success.

At 6:45 pm a notation was made at 325th Regimental Headquarters stating there was a call from E Company that it needed help, followed later that evening by a call for ammunition to that company’s right flank.

“I remember ammunition getting low,” Sartain said. “It was a bad situation. I told them all, be sure you know what you’re shooting at.” Though the need for ammunition remained, 325th Regimental records indicate that at 7:53 pm a jeep loaded with ammunition was to be stopped en route. Presumably this was not because the need for ammunition replenishment had passed but because the road to E Company’s position on Finger Ridge had been cut.

About this time Lieutenant Fellman came bounding into a foxhole where Sartain was reminding one GI to pick his targets carefully. The captain was doing his best to be everywhere at once, but of course that was impossible. Sartain shouted in Fellman’s ear, “Get down to the other side of the OP. Tell those boys over there not to go hog wild shooting off their ammo, and make sure they keep their asses put!” With a slap on the back, Fellman was off. Sartain felt better, knowing he had one of his own officers out there, encouraging the troops with him.

The fighting was now at such an intensity the reports of individual weapons couldn’t be distinguished. Then one German soldier got up and rushed forward. He tossed a stick grenade toward the Americans, even as he was cut down by rifle fire. Another did the same and was killed as quickly as his comrade. It was suicidal of them to do so, but in the intoxication of battle soldiers often take risks that no “sane” man would ever consider.

Ed Ryan, a radioman with the 319th’s Headquarters Battery, wasn’t on Finger Ridge that day, but he’d found himself in the middle of plenty of hammer-and-tongs firefights. Describing the experience of losing one’s sense of danger, he said, “When you get into that kind of combat, different people act different ways. There’d be so much fire you’d get so scared that you couldn’t handle it anymore. You get scared to death, then it seemed like the adrenaline would take over. You’d get this adrenaline rush and it’d stay with you, then you didn’t care anymore.”

Recalling the Battle at Finger ridge

The Germans were never able to breach the Finger Ridge position, though some of them fell only yards from the American foxholes. The enemy pulled back, regrouped, and in the growing twilight hit the GIs again. “They would attack us, then settle down, then attack us again. Eventually the one with the flamethrower quit, but not until well after dark,” remembered Sartain.

Everybody on Finger Ridge felt they’d avoided being overrun by a hair’s breath, and they were right. Though more fighting was expected, ammunition was low and the isolated platoon never did get any reinforcements. Lest they be taken by surprise, Sartain and Manning knew that the men would also have to remain awake and alert, fighting exhaustion now that darkness was upon them.

“All that night we could hear them out there,” Sartain said. “We’d send up some illuminating shells and light up the battlefield. You could see them scurry for cover. In the daylight you didn’t have to worry because you could see what they were doing. But they didn’t attack. The Germans didn’t like to fight at night, they just didn’t. We found that out early.”

Though there were no further assaults, the Americans were nervous and would sporadically let loose with outbursts of fire whenever they heard noises or flares gave them a target to shoot at. But as the hours advanced closer to dawn, these incidents ceased, a gentle rain started falling, and the field became quiet.

Sartain continued his story of Finger Ridge: “They picked up their wounded and dead after dark. They never had a white flag to come pick them up, and I kept wondering why, but once it got to be daylight they withdrew. It was unreal. You’d think nothing had happened; all that commotion going on, all that afternoon and the night before.”

The two captains remained at the Finger Ridge position until late morning, by which time it was clear that the Germans had no intention of renewing their attacks. Moving from foxhole to foxhole, Sartain reviewed the essentials of their defense with the individual infantrymen who had displayed the most leadership. Before parting, he’d tell them, “All right, tiger, you know what to do. Carry on.”

Meanwhile, Captain Manning reviewed things with Lieutenant Fellman, making sure he was familiar with every preregistered concentration point on the map and its corresponding location on the flatlands before them. Content that the situation was stabilized, Manning and Sartain left Finger Ridge.

Back at the jeep, Sosa had a canteen cup of coffee waiting for each of them. They sat down and drank deeply, suddenly aware of how thirsty they were. Then Sartain remembered his pipe. He took it out and slowly prepared to smoke it. Manning pulled off his helmet, placed it beside him, and ran fingers through his matted hair. No one said anything. It was obvious to Sosa that his captains were exhausted. He wouldn’t bother them by asking where they’d been since yesterday afternoon. After all, from the sounds of battle that had drifted over the ridge, Sosa had a pretty good idea.

When Sartain and Manning were finished with their coffee, Sosa started the jeep and drove off toward battalion headquarters. The light rain had cleared off and, as he drove, Sosa noticed both captains had fallen asleep.

As the jeep approached 319th Headquarters, Sosa’s passengers roused themselves. Major Silvey was already waiting outside the command tent and trotted up to the jeep as it rolled to a stop; Colonel Todd, the battalion commander, was following a few yards behind, shouting greetings. Sartain remembered, “They were glad to see Manning and me. I guess both Headquarters and A Battery were kind of concerned about our butts.”

Inside the command tent, Manning and Sartain took seats at a folding table. They hadn’t eaten since the fried eggs Sosa had made the day before, so Todd saw to it that they were brought some hot chow. Even though the food was a strange amalgam of American, British, and German rations, the famished officers scarfed it down with great efficiency, followed by a period of debriefing.

The two captains told of the absence of infantry officers, the repeated frontal assaults, the German armor, the flamethrowers, and the way the batteries had saved the position. All the while Major Silvey took notes. Other officers and enlisted men who were within earshot, or who came by in the course of their duties, couldn’t help but linger and listen in.

Of course, it was only a matter of minutes before details of the Finger Ridge battle were being passed from man to man throughout the battalion. Manning and Sartain were already held in high regard, but now their reputations soared. As Sartain said, “They made a big deal out of it.” The men were also projecting the pride they felt in their own accomplishments onto the two captains. According to Sartain, “It was a high point for the men, particularly in A Battery. I really believe if they had any feelings about me or Manning, it increased their respect, I really do.”

After the debriefing was over, Colonel Todd suggested that the two get a few hours’ sleep. By now it was clear to anyone familiar with the events of September 25 that Manning’s and Sartain’s actions on Finger Ridge were something extraordinary and worthy of recognition. Colonel Todd and Major Silvey certainly thought so, and when Colonel Andy March, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division Artillery, stopped in shortly afterward he thought so, too.

Todd began investigating the idea of nominating them for decorations. Decorations required corroborating written statements that then needed to be reviewed by a board of officers from outside the unit. All this would take some time, and for the present Sartain and Manning still had their jobs to do.

“The German Soldiers—They Were Just Kids”

Sixty-five years later, Sartain was still proud of but also perplexed by what took place on Finger Ridge. “On reflection,” he said, “I’ve never understood why there were no NCOs or officers with this group, or why—once we were under attack—the infantry battalion did not send reinforcements. We got absolutely no reinforcement from their headquarters. We had no contact with the infantry battalion, and that just amazed me. It was like those kids were stuck out there and nobody even knew they were there.

“But those kids on that ridge, they did all right, they really did. Nevertheless, if it hadn’t have been for Manning and the artillery, and the way he conducted the artillery fire, we couldn’t have held on. If it hadn’t been for Manning, we never would have survived.”

As far as the Germans who attacked Finger Ridge are concerned, Sartain remained puzzled by them as well. True, their performance at Finger Ridge displayed determination, doggedness, and even valor. But it plainly lacked ingenuity, and the attacks were poorly executed. For example, there were the simplistic frontal assaults by the Germans in the face of repeated failures. Their methods had a primitive and amateurish quality suggestive of inadequately trained soldiers.

Sartain commented, “I don’t know who it was, but I don’t think it was SS because they continued their frontal assault. And a couple of them that were killed pretty close to us looked like real young kids. That’s the thing I was shocked about in Holland, the German soldiers—they were just kids.”

The inexperience and youth of the Germans was so apparent that, even in the heat of the battle, Sartain and Manning couldn’t help feeling pity for them. Reflecting on this years later, Sartain suddenly remembered one peculiar episode during the fight that illustrated this point.

“Manning was shooting at people out there with the artillery when this kid rose up out of the grass,” he recalled. “He was shooting up at us, but he was just a teenager, less than a teenager. He may have been older than he looked but he wasn’t much taller than the grass he was in. I motioned to Manning, pointed to this kid and Manning realized he was just a teenager, too. We called off the fire on that particular concentration. We held up fire on him, just held up the fire till I felt like he was out of the way. Manning moved the fire off to other concentrations. Then that kid squatted down in the tall grass and he was gone; we never saw any more of him again.”

Why the Germans never employed anything beyond the most archaic of tactics remained a mystery for Sartain. “I couldn’t understand why they didn’t try and make a flanking attack. I couldn’t understand why they kept coming at us straight on. I mean, they never gave up, and when they continued the frontal assault they were just artillery meat.”

The failure of the Germans to depress their 20mm guns enough to bring them to bear effectively on the American position was another indication of their lack of proficiency. When coupled with the youth of some of the enemy casualties that Sartain recalled, it is apparent that the Germans were deploying underage and ill-trained troops as the war dragged on.

Epilogue

September 26 was a chance for the men to clean up and get some rest. Many had not touched razor to face since landing in Holland, and by now the higher brass were complaining to Colonel Todd about their scruffy appearance. Taking advantage of the lull, water was heated up in helmets and the beards disappeared.

Later that afternoon the seaborne element of the 319th arrived from England, having crossed the Channel and driven clear across France. With them was a small convoy of 2½-ton trucks loaded with much-needed supplies, as well as the first mail delivery since the battalion had landed by glider on the 18th. When news spread to A Battery that the mail was in, the mail clerk went up to Battalion HQ to retrieve it. A little while later he was back at the battery, ready to distribute the mail and crying out, “Hey, hey, hey, we’ve got mail today!”

There were several letters for Captain Sartain, including birthday greetings from his parents and fiancée, Peggy Lou. In all the activity of the invasion, it had never occurred to him that his birthday had come and gone.

Nice article, in general, interesting insight into small unit actions and the value of leadership.

It needs correction with regards to the flame thrower. Compressed nitrogen is the propellant not the “burning agent” which was usually some sort of thickened gasoline. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flammenwerfer_35. If you are going to go into that much detail on a weapon at least look it up on line and get it right.

Additionally the 20 mm fire was likely high because the Americans were above the enemy, properly positioned near the military crest of the hill. As the Germans approached they had to shoot at higher angles causing the fire to be high. If the Germans had possessed a few mortars they could have wrinkled out the Americans in short order.

Never found out where there officers were.

I know this story is not about glider pilots but the rank and full names of the Glider Airborne is listed on the photo “Flak Happy” and only the name Marks is listed. I thought it would also be appropriate to list the rank and full name of the Glider Pilot, who got the members of the 319th Communications Section, that were in his glider, down safely. The glider pilot was Flight Officer William Marks with the 37th Troop Carrier Squadron, 316th Troop Carrier Group. In his intelligence report given on his return on 28th of September, he reported that their take-off time was 1135 on 18 Sept. and they were over the LZ at 1440.

They encountered heavy fire during landing and 88mm cannon after landing along with heavy small arms fire. Their landing location was 5 deg. 57 min 30 sec E / 51 deg. 47 min N. In the report he continues to list his actions on the front line and that they were strafed by flights of about 8 ME 109s and FW 190s in morning and afternoon of the 19, 20, 21. His only complaint was that he could have used an airborne bed roll.

Kind Regards

National WWII Glider Pilots

Dear Patricia,

After seeing this article again, I felt it necessary to comment via a reply: Here it is.

RE: 1. SOURCING REQUIRED – – The image of “Flak Happy” is the PROPERTY OF (then) Flight Officer William Marks who served our Nation for 33 years 10 months 15 Days, retiring from USAFR at rank of Major, and NOW MINE. There is another image with the troop NOT aiming his weapon over the head of his fellow Warrior. 3. Private Englander wrote F/O Marks a letter to update him on the progress this unit accomplished and requested COPIES of the photo taken by F/O MARKS that morning.

RE: NAMES of troops: 1. THAT morning before takeoff, F/O Marks scribed the names/addresses/NoK with the promise to write each when he returned to Cottesmore AFB that he’d landed them safely. 2. 1984 I USED that list to trace down four of the seven troops whom F/O Marks flew in on 18 September 1944. 3. There is more to this story than depicted in this article. THE LIST, as written by Marks: “First Sgt. Rosenwasser” & “CPL Ernest W. Osborne” & Johnnie S. Moore” & SGT> Jarret A. Fury” & Pvt. D. Vassill” & Cpl Ed Ryan” & “PFC S. Englander (Seymour)” There is nothing like an original document, written THAT DAY, for accurate information.

RE: “glider pilot Marks” is my FATHER. 1. The original tow pilot communicated to Marks the C-47 was experiencing engine malfunction and would have to pull out. Marks got out of the glider, approached the Flight Line OIC and “demanded” another Tug. 1st Sgt. Rosenwasser instructed Cpl Ed Ryan to ” …follow the pilot and make sure nothign bad happened.” QUOTE from Cpl. Ed Ryan.

RE: Photos – Marks carried his own camera and requested 1st Sgt Rosenwasser to snap photos of the FLIGHT OVER to LZ – T. There was an exchange of conversation between Marks and Rosenwasser that I have in my files; Once Marks “cut off” to land, he and Livingston make a sweeping turn OVER the German border to land; The German Army was dug in at the tree line so unloading took the Troops and Glider Pilots to fight back and then the lull appeared and the gliders were unloaded. There are also images of unloading the gliders and Testimony of those who WERE THERE, including the German Army Ambush on 24 September 1944 of the Glider Pilot’s Evacuation Convoy requiring Marks to go up front with his buddy F/O William Rufus Livingston joining the Brits to fight off the onslaught of the German Army. Marks and Livingston were pressed into Forward Observer Duty to measure the German Army movements; they were moving their self propelled 88’s to do more damage to the convoy, Three Shermans were called in from the 44th RTR, upon arrival they were taken OUT by the 88’s.

QUESTION: How many Officer Pilots, 1. Wore a Steel Pot (combat helmet), or carried a THOMPSON? Marks and Livingston did and they used them.

I’ve a photo of Marks and Livingston and McRae (landed in the next wave a few days later) in FULL BATTLE DRESS, Marks and Livingston with their THOMPSONS and McRae with his M-1 Carbine. BATTLE DIARY: Marks kept a battle diary of his and Livingston’s 10 Days of Ground Infantry Combat Duty before they were evacuated. Marks and Livingston were the LAST Glider Pilots to return to Cottesmore AFB.

SO when the Glider Pilots are NOT given credit for being on the Front Lines, then shame on those who write these kinds of articles.

AN APOLOGY would be a good start.

I’ve STOOD on LZ – T, (Twice with two visits to England and the Continent) with the GPs who landed LZ-T and on LZ-N with ground troops and fought along side those very same troops because General Gavin’s MTOE was at 65 %. I’ve 36 years of Interviews, both written by me and on film, with these great guys, The Greatest Generation and WARRIORS themselves.

Later, in Operation Varsity (aka Burp Gun Corner), based on the requirement that Operation Market Garden Glider Pilots were used in Ground Infantry Combat Duty, VARSITY troops were given approximately 30 days of combat training.

I’m also told that Combat Photographers were not deployed on Market Garden because it was deemed too dangerous. I believe that to be true.

Greg Marks – Son of William Marks, WW II Veteran and Officer Pilot and member of World War II Glider Pilot Association (now Committee).

LAPD Policeman 3 + 1 Senior Lead Officer (retired) “There is no such thing as a ROUTINE radio call or Traffic Stop”: member American Legion (Mine Honor and Life both grow in One, THEREFORE Death Before Dishonor is not an option.)