By Joshua Shepherd

For the men of the 28th Marine Regiment, the morning of February 19, 1945, brought a sobering moment of truth. Attached to the 5th Marine Division, the regiment was scheduled to hit the beaches of Iwo Jima, an obscure volcanic island in the northern Pacific. As they neared the Island, the Marines, crowded aboard landing craft, had grown uncharacteristically subdued. Private Jim Naughton of the Third Battalion, 28th Marines, Fifth Marine Division, recalled the somber mood as the men prepared to approach the heavily defended Japanese shoreline. “Nobody talked,” he said, “God only knew what was ahead of us.”

When the ramps of their landing craft lowered, the men were greeted with surreal horrors that survivors would never forget. The beach was little more than a chaotic charnel house. The deafening roar of Japanese artillery fire rocked the entire shoreline, and the terrifying rattle of enemy machine-gun fire made movement nearly impossible. Officers shouted to bring order to their commands. The wounded cried out in terror.

The entire length of the beach was crowded with the wreckage of American vehicles shattered by Japanese fire. Worse yet, the mangled bodies of dead and wounded Marines were strewn indiscriminately in every direction. It was a stark introduction to the island of Iwo Jima. In little more than an hour, the deceptively placid shoreline had been transformed into an appalling killing field. “It was a terrible- looking sight,” recalled Corporal Charles Johnson, also of 3/28 Marines. “I looked at the beach, and it was like hell on earth.”

For the warriors who would do battle for the rocky wasteland, Iwo Jima would, indeed, become a hell on earth. But the struggle for the seemingly insignificant island had become an unavoidable strategic objective in the American drive toward the Japanese homeland.

By the end of 1944, the Japanese Empire, once the undisputed scourge of the Far East, was on its heels in a wide arc across the Pacific. U.S. Army forces under the command of General Douglas MacArthur had pressed into the Philippines by that autumn. At the same time, the 1st Marine Division secured the island of Peleliu after a bloody two-month struggle.

For the Americans, perhaps the greatest prize of 1944 was the Mariana Islands, where the Marines captured Guam, Saipan, and Tinian. Captured during a hard-fought series of engagements beginning in June, the Marianas constituted a key stepping stone for Army Air Forces tasked with the reduction of Japan. Situated just 1,500 miles from Tokyo, the Marianas were soon home to airfields that could accommodate the B-29 Superfortress, the most fearsome bomber in the American air fleet.

Under the aegis of the 20th Air Force, B-29 crews operating out of the Marianas would soon bring the realities of total war to the Japanese homeland. Flying under cover of darkness and at low levels, the B-29s unleashed a fire-bombing campaign that wrecked Japan’s industrial capacity. Large portions of Japan’s major cities were reduced to ashes as the 20th Air Force delivered its own form of grim retribution.

The air campaign, though, was not without its risks. Any B-29 unlucky enough to be crippled over Japan faced a virtual death sentence in the waters of the Pacific. Worse yet, one particular island, which was situated 750 miles north of the Mariana Islands, was proving to be a nettlesome obstacle for the American air campaign. Although on some American maps the land mass appeared as Sulfur Island, it was destined to be remembered by the Japanese name of Iwo Jima.

At first glance, Iwo Jima was seemingly unimportant. The island was a rocky, arid, and inhospitable island that, due to a lack of fresh water, was barely habitable. But the island sat astride the most direct route from the Marianas to Japan. Japanese forces had transformed Iwo Jima into a forward defensive base, constructing radar installations that could detect incoming American bombers and give advanced warning to the mainland.

Additionally, the island boasted two airfields, with a third under construction. Incoming American bombers, which were forced to fly without their own fighter escorts, were attacked with impunity by fighters based on the island.

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff had decided by October 3, 1944, that the reduction of Iwo Jima was imperative and ordered the seizure of the island. As plans were developed, the top brass opted to throw overwhelming force against the island, eventually mustering the largest amphibious force assembled during World War II. Approximately 80,000 Marines drawn from the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Marine Divisions would conduct a direct assault against the Japanese forces on the island. Backing up the Marines would be an immense armada of eight hundred vessels. The ships would include scores of troop transports as well as aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, all of which could bring enormous heavy firepower to bear against Japanese positions before the infantry landings.

Operation Detachment, as the invasion was designated, would be led by some of the most experienced senior officers in the Pacific Theater. Overall command of the nearly 250,000 men who would carry out the operation was assigned to Admiral Raymond Spruance, a gifted naval officer and key fleet commander since the American victory at Midway in June 1942.

Overall command of landing forces was assigned to Lt. Gen. Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith. But direct field command of the three divisions that would do battle for Iwo Jima, known collectively as the V Amphibious Corps, fell to Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt, an unassuming career officer known to combine a keen intellect with aggressive Marine spirit.

Such Marine grit would be sorely needed, as the terrain of Iwo Jima itself constituted an infantryman’s nightmare. Just eight square miles in size, the island was eight hundred yards wide across its southern neck but flared out to two and half miles wide in the north. Allied planners famously observed that the island resembled an inverted pork chop.

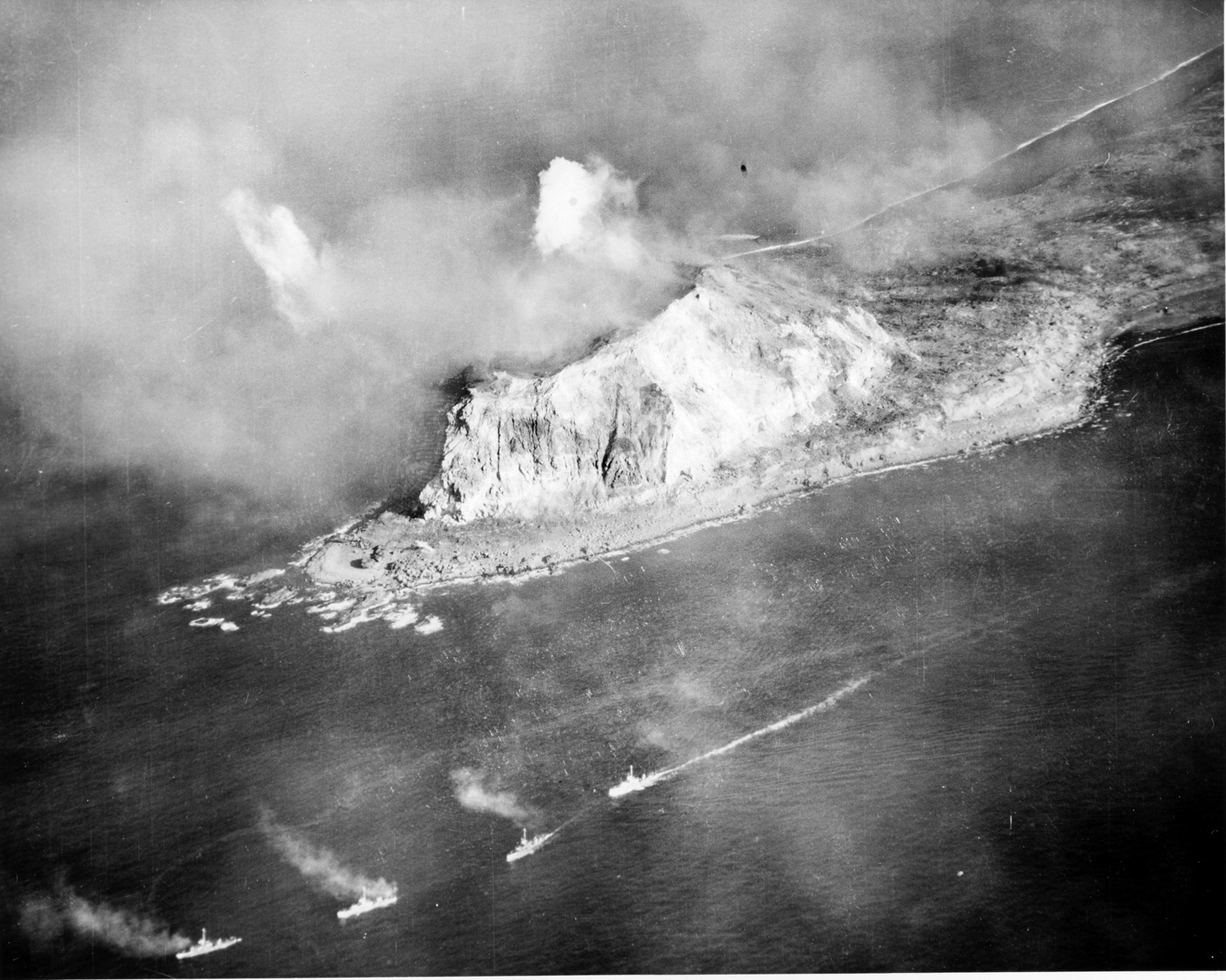

At the extreme southern tip of the island towered Mount Suribachi, a 500-foot-tall dormant volcano that was honeycombed with concealed artillery positions. The center of the island contained some stretches of flat terrain, dotted with two airfields and a handful of small villages. The northern reaches of the island were characterized by steep gullies and plunging ravines that were ready-made for defense. To secure lumber, Japanese engineers had stripped the island of trees, rendering much of Iwo Jima a rocky wasteland void of vegetation. The island’s water supply consisted entirely of a few wells augmented by cisterns built to capture rainwater.

Awaiting the American assault force was an impressive network of fortifications manned by some of the most fanatically determined troops in the Japanese Empire. Although possessing a decided defender’s tactical advantage, the Japanese would be badly outnumbered. The island’s garrison numbered 21,000 men, most of whom were infantry, augmented by artillery and anti-aircraft units. A token armor contingent, the 13 vehicles of the 26th Tank Regiment, also was stationed on the island, as were naval support troops that included engineering and supply outfits.

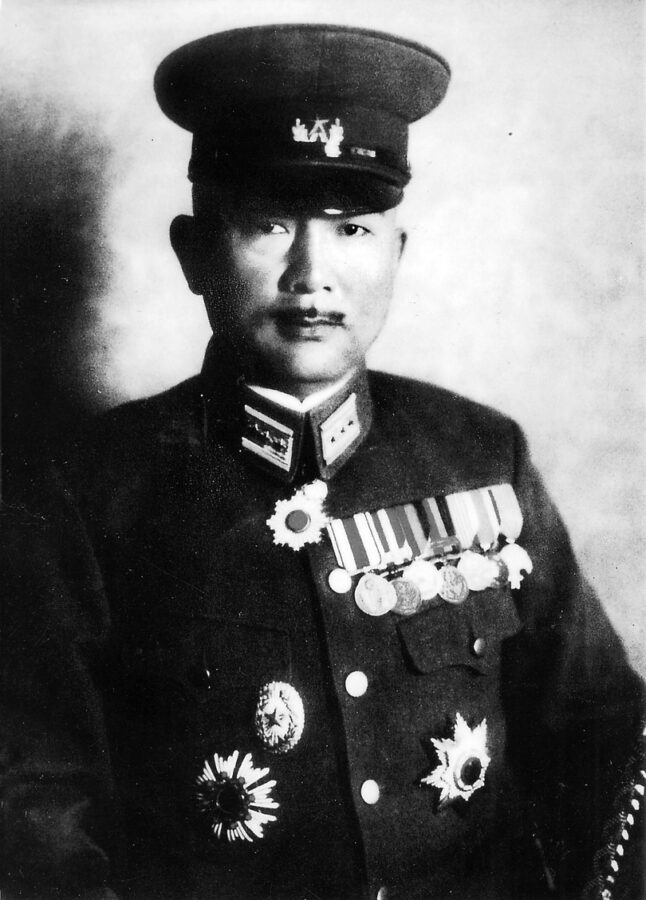

In addition to dedicated foot soldiers, Japanese defenses on Iwo Jima benefited from the presence of Lt. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi, widely regarded as one of the best field commanders in the empire. A seasoned veteran with three decades of experience, Kuribayashi descended from Samurai stock and possessed a steely resolve to serve his emperor.

Given command of the island defenses in May 1944, Kuribayashi used the remainder of the year to good advantage. Under his direction, skilled Japanese engineers worked feverishly to carve an impressive warren of underground bunkers, artillery emplacements, pillboxes, barracks, and command posts. Much of the island was connected by a dizzying labyrinth of underground tunnels, ensuring that Japanese fighting positions were mutually supporting, heavily fortified, and well concealed.

With prescient strategic thinking, Kuribayashi decided to jettison long-standing Japanese defensive doctrine in confronting amphibious landings. At Tarawa, Peleliu, and Guadalcanal, Japanese forces had opposed enemy landings by confronting the Americans directly at the beachheads, mounting a rigorous defense at the shoreline in a desperate attempt to forestall an invasion before it could proceed inland. Kuribayashi realized that such an approach had been both costly and futile in the face of superior American manpower and materiel.

Despite heated opposition from his subordinate officers, Kuribayashi decided on a novel approach. He would allow the Americans to land unmolested, wait until the beaches were crowded with men and vehicles, and then unleash coordinated and pre-sighted artillery fire that would tear the Marines apart.

America’s ability to project military power was starkly evident when the U.S. Navy’s big ships began marshalling off of Iwo Jima. To soften up Japanese positions before the landings, the Americans planned a massive bombardment. Working out the details, however, occasioned no small amount of head-butting between Navy and Marine officers. For their part, generals Smith and Schmidt requested 10 days of naval gunfire before the invasion. Told that they would receive only three days of bombardment, both men sharply protested but were turned down by Spruance.

Ultimately, the Iwo Jima defenses were subjected to a brutal pounding from sea and air. Army B-24 Liberators operating out of the Marianas had bombed Iwo Jima every day beginning in December, and Rear Adm. William Blandy targeted the island for three days beginning on February 16. Blandy wielded impressive firepower from the Navy’s older battleships, including the Arkansas, Texas, Nevada, New York, Idaho, and Tennessee, which collectively mounted seventy-four big guns.

Blandy’s “Old Ladies,” as these battleships were known, mercilessly shelled Iwo Jima for three days, but when the smoke cleared, the results were disheartening. It was apparent that the intense bombardment had barely put a dent in enemy defenses, and Japanese counter-fire revealed that the island was defended by many more concealed artillery positions than initially thought.

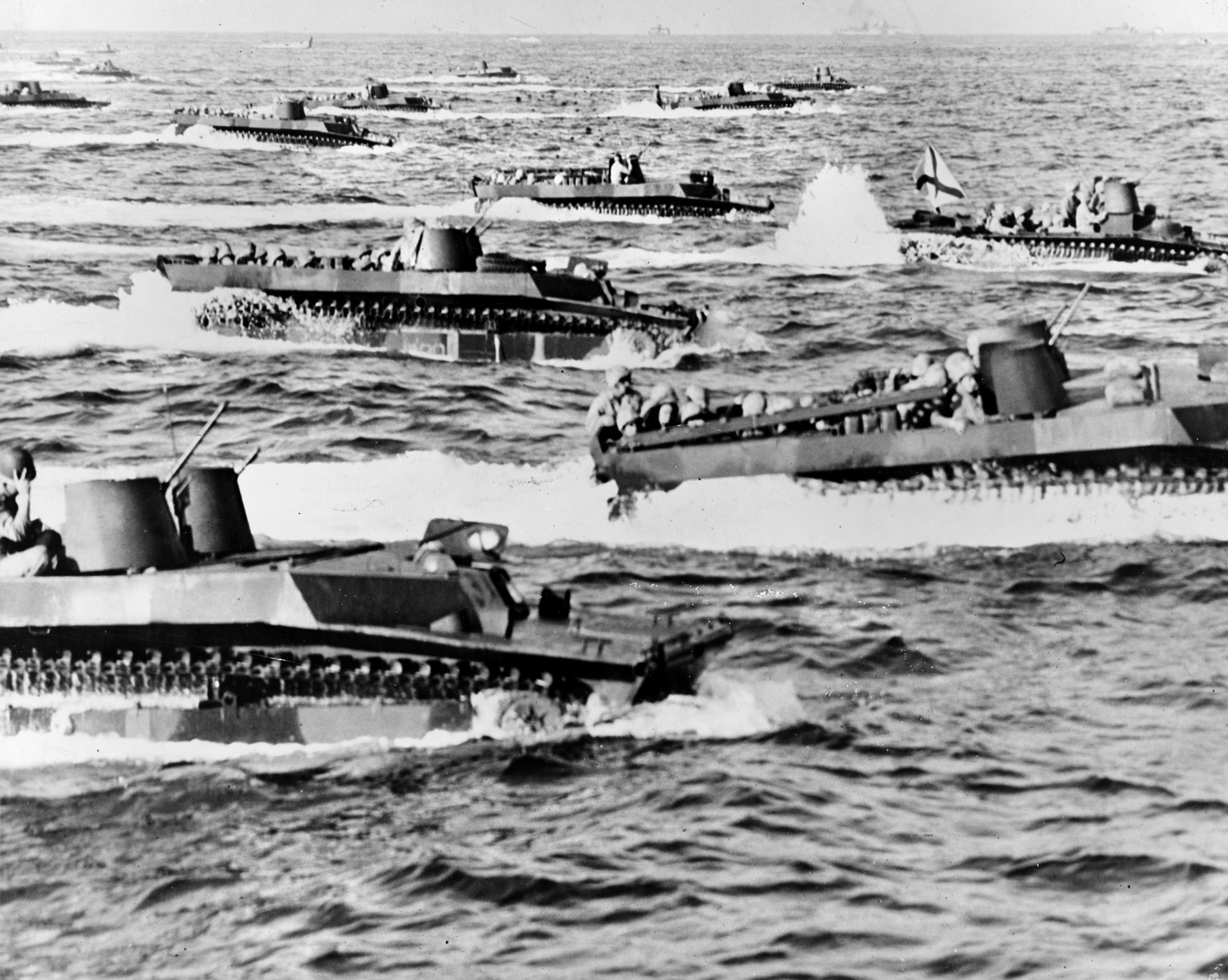

Despite the results of the disappointing naval bombardment, the amphibious landings would be carried out as planned. Following another shelling of the island, the invasion would be spearheaded by 68 LVT Amtracs—amphibious vehicles mounting 75mm guns and three machine guns. The vehicles were intended to push inland about 50 yards, providing covering fire for the infantry and tanks that would constitute the primary landings.

Stretching north from Mount Suribachi were expansive beaches which, at least from aerial reconnaissance, appeared ideal for infantry landings. The beach was divided into seven landing zones, and the initial infantry landings would consist of eight battalions of Marines. Individual waves of landing craft were scheduled to make landfall every five minutes. If all went according to plan, it was hoped that the entire job of securing Iwo Jima could be wrapped up in 10 days.

Months of preparation finally came to fruition early on the morning of February 19, 1945, which was designated as D-Day. While the Marines assigned to the initial assault waves nervously boarded their landing craft, the Navy’s big guns opened up yet again, battering suspected Japanese positions from Mount Suribachi north to the airfields. It was the largest bombardment ever seen in the Pacific, raising immense clouds of smoke and dust high in the air. The naval gunners held their fire just long enough for 120 carrier-based aircraft to strafe the beaches, at which point they opened up again.

Under cover of the bombardment, the first assault waves were ordered forward. The first armored LVT(A)s hit the beach at 8:59 a.m., but their attempts quickly degenerated into a fiasco. Contrary to intelligence reports that described the landing zones as ideal, the beaches were actually made up of coarse, black, volcanic crystals that were nearly impassable to both men and vehicles. Failing to get traction, some of the vehicles bogged down; others backed up into the surf and opened fire from the water.

As Marine infantry began pouring onto the beaches in five-minute intervals, their progress was no better. Moving forward on the loose volcanic ash was difficult enough, but running across it was impossible. And there were more unpleasant discoveries. Rather than finding a level exit to the mainland, the assault troops found their path blocked by a formidable 15-foot-high terrace of volcanic ash. The beaches quickly became packed with men as the troops frantically scrambled their way forward, with little success.

Curiously enough for the Americans, opposition to the landings was light. For about 30 minutes, the Japanese response was negligible— confined to sporadic small-arms and mortar fire. Naval officers entertained hopes that the pre-invasion bombardment had indeed shattered Japanese defenses. New recruits thought that perhaps Iwo Jima would be a pushover after all. Veteran Marines who had already fought their way across the Pacific knew better and braced for the worst.

As units struggled their way up the berm and got organized, officers prepared to lead their men over the top. The initial plan to expand the beachhead called for cutting the island in half and seizing Airfield No. 1. On the right, the 25th Marines would swing north toward a locale known as the Quarry and anchor the right flank. To their left, the 23rd Marines would push straight ahead toward the airfield, while the 27th Marines would attack toward the left and swing around behind the airfield. On the left, the 28th Marines would drive straight ahead, reach the opposite coast, and isolate the Japanese garrison on Mount Suribachi.

The Japanese had other plans. After waiting for the beaches to become clogged with men and vehicles, Kuribayashi finally gave the order for his men to open up. A terrific storm of artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire suddenly fell onto the crowded beach. With so many men bunched up and barely able to move forward, Japanese gunners exploited a rich target. The Japanese had pre-sighted their guns and possessed precise ranges along the beachhead.

The shoreline quickly became a charnel house as the terrifying roar of artillery fire swept across the landing site, littering the ground with dead and dying Marines and dozens of wrecked vehicles. Pressing forward was the only alternative to annihilation, and officers and non-commissioned officers acted quickly to get the men moving. “Okay, you bastards, let’s get the hell off this beach!” shouted Lt. Col. Chandler Johnson, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, to his men, who were deployed on the left. As the Marines finally succeeded in trudging over the top of the terrace, officers organized their outfits and charged forward.

Rushing ahead through a steady rattle of Japanese machine-gun fire, the men of the 28th Marines executed a wild attack across the island in order to cut Japanese defenses in two. It was a chaotic fight, carried out by the grit and determination of isolated knots of men. Marines assaulted and overran dozens of pillboxes, tossing grenades through the embrasures and killing anyone who survived the blast.

After coming to grips with the enemy, the Marines were worked into a killing frenzy. Private Lee Zuck of the 1st Battalion, 28th Marines, mounted the top of a 20mm gun position, and as the Japanese fled for the rear, he coolly gunned down the entire eight-man crew. Captain Dwayne Mears fought with nothing more than his .45-caliber sidearm, repeatedly attacking pillboxes and killing the defenders at close range.

The Marines suffered 2,500 casualties on the first day.

Despite such heroics, the Marines were paying a fearful price in casualties as they ran the gauntlet of enemy fire. Men fell by the score, dying and suffering alone, while overwhelmed Navy corpsmen struggled to help those they could. After an hour and a half of determined fighting, breathless Marines began reaching the west coast, but their hold on the ground was tenuous at best.

Lieutenant Frank Wright of the 1/28, who had started the attack at the head of 60 men, found that only two men had come through with him; the rest of his command was either dead, wounded, or lost. Lieutenant Wesley Bates had fared little better, reaching the west coast with less than a half dozen men from his platoon. Marine officers, who led by example, suffered badly. In the 1/28th Marines, only one company commander was still on his feet.

Farther to the right, the men of the 27th Marines ran into stiff opposition as they struggled to exit the beach. Facing certain death as Japanese artillery continued to rake the shoreline, Marines fought their way up the berm and pushed inland. As elements of the 27th Marines skirted across the southern end of the airfield, they fought a bitter battle with Japanese troops.

Conditions on the landing beaches steadily deteriorated as tanks and vehicles continued to land but had nowhere to go. Wreckage clogged the shoreline until Navy beachmasters, working closely with Seabees, began clearing crippled vehicles and cutting exits through the beach terrace that could accommodate American armor.

But even with armor finally joining the fight, every inch of ground was hotly contested. Well-placed Japanese anti-tank guns ensured that American tank crews could only move forward at an agonizingly slow pace. On the Fourth Division landing beaches on the right, enemy resistance was particularly fierce. The Marines ran into a Japanese minefield, and engineers carefully probed their way through.

One of the prime objectives of the day was the Quarry, a forbidding swath of high ground that commanded the American right. The assault was assigned to Lt. Col. “Jumpin’ Joe” Chambers of the 3rd Battalion, 25th Regiment. Chambers led a spirited attack into the crags of the ridge and slowly drove out the Japanese. By late afternoon, his Marines sat astride the ridge but had paid a fearful price. The 3rd Battalion was down to a skeleton force of 150 men. Company L of the battalion, which had started the fight with 240 men, could muster no more than 18 Marines.

Such dogged Japanese resistance bogged down the Americans, and as darkness approached, orders went out to halt the attack and sit tight for the night. Marines who were exhausted and numb from the day’s fighting dug in as best they could and faced a tense night under the constant threat of a Japanese counterattack.

Although the first day’s fighting had not advanced as far as initially planned, the Americans had secured a respectable lodgment on Iwo Jima. From the west coast near the base of Mount Suribachi, the Marines occupied a ragged line that stretched northeast across the island toward the vital ground at the Quarry. Airfield No. 1, another one of the prime objectives of the day, remained in no-man’s-land.

The landings had succeeded in placing 30,000 men, bolstered by armor and artillery, squarely ashore the island, but the beaches remained dangerously crowded with men and tangled with immobilized vehicles.

The first day’s battle for Iwo Jima had come at a fearful cost in blood. In the midst of the hotly contested battlefield, it was simply impossible to extract all the wounded. Although 1,000 men were evacuated during the day, the beach was littered with terrified, broken, and helpless men who desperately needed medical attention. Japanese mortar fire continued to fall indiscriminately, twice hitting aid stations. The sights and sounds of the first night on Iwo Jima was a “nightmare in hell,” observed Time-Life correspondent Robert Sherrod.

The nightmarish struggle for Iwo Jima was only beginning. At dawn on the following day, naval aircraft hit the slopes of Mount Suribachi, dropping bombs and napalm in a merciless effort to soften up Japanese defenses. The 28th Marines, though, could make little progress toward the mountain, gaining no more than 200 yards of ground after a day of heavy fighting. With little vegetation or natural cover in front of them, the Marines simply could not make swift progress up the mountain. Second Lieutenant G. Greeley Wells of the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment lamented the exposed approaches toward the mountain. “My men would be open targets all the way,” he said.

Farther north, the Marines had just a bit more luck. Naval guns once again shelled Japanese positions, pummeling a wide swath across the Marines’ front before the infantry push. While troops held fast at the Quarry, the attack was pressed hard on the left. At Airfield No. 1, the men of the 23rd Marines advanced into the teeth of heavy Japanese machine-gun fire, made a mad dash across the tarmac, and succeeded in holding the airfield. By the end of the second day, a cohesive American line stretched from coast to coast.

Over the next two days, Japanese determination and foul weather combined to frustrate further gains. In the north, General Schmidt continued to straighten his lines and push his men forward, but gains were negligible. In the forbidding terrain of the Quarry, Marines encountered a mystifying maze of enemy defensive positions and suffered heavy casualties. On D+2, the Americans gained just 50 yards.

At the base of Mount Suribachi, the 28th Marines experienced better progress. The mountain was initially defended by nearly 1,000 Japanese troops under the command of Colonel Kenehiko Atsuchi. Although Atsuchi’s troops were resolute fighters, they were entirely cut off from Kuribayashi’s main body in the north. The mountain defenses likewise took a steady pounding from Navy vessels, Marine artillery, and aircraft.

Marine tanks found it impossible, though, to operate at the foot of the mountain, leaving a tough fight for the infantry. On February 22, the 28th succeeded in making good, if costly, progress against Suribachi. After a series of vicious close-quarter fights with small arms and flamethrowers, the Americans slowly began working their way up the lower slope. After several days of incessant combat, Atsuchi had lost hundreds of his men, and it was clear that Suribachi was ripe for the taking.

Early on the morning of February 23, a four-man patrol nervously scouted up the north face of the mountain. Although expecting to receive enemy fire at any moment, the men reached the summit of the mountain. Convinced that enemy defenses on Suribachi had nearly collapsed, Johnson ordered 40 men up Mount Suribachi to seize the crest. As the commander of the attack, Lieutenant Harold Schrier of 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment, turned to head up the mountain, Johnson handed him an American flag carried by his battalion. “Put this up on the hill,” the colonel said.

Schrier’s party fought their way through light opposition from isolated Japanese and reached the summit a little after 10:00 a.m. Using an old pipe as an improvised staff, the Marines raised their flag above Suribachi in plain view of nearly the entire island. Standing off the coast, Navy vessels blared horns and whistles. Marines on the beaches shouted and cheered; others wept.

At the base of Mount Suribachi, Johnson realized something big was afoot and snapped at a nearby lieutenant. Someone up the chain of command was going to want the battalion flag, but he is not going to get it, warned Johnson. “That’s our flag, “he said. “Better find another one and get it up there.” A larger flag was located, measuring roughly four by eight feet, and carried to the summit. With little fanfare, six Marines raised the new flag above Suribachi. Fortunately for history, Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal captured the moment on film, preserving the most iconic moment in the history of the Marine Corps.

Despite the inspiring flag-raisings above Mount Suribachi, the bloody fight for Iwo Jima was far from over. The 28th stayed on the mountain to mop up Japanese survivors, who remained hidden in the underground tunnel system. But with Mount Suribachi in American hands and Japanese guns on the mountain silenced, General Schmidt was able to concentrate all of his efforts into the drive against primary Japanese positions in the north.

Ultimately, the entire V Amphibious Corps would be committed to the fight. On the American left, Maj. Gen. Keller Rockey’s 5th Division advanced along the west coast. Maj. Gen. Graves Erskine’s 3rd Division was assigned the drive up the center of the island. On the American right, Maj. Gen. Clifton Cates’ 4th Division faced a tough fight in the heavily defended and forbidding terrain that hugged the eastern coast.

On February 24, five days after the initial landings, the drive north began in earnest. Naval and air bombardment continued unabated against Japanese positions, and the ground attack was aimed at Airfield No. 2, which was defended by an impressive complex of as many as 800 pillboxes. While enemy artillery and machine-gun fire raked the runways, the Marines of the 21st Regiment prepared to move forward. Lt. Col. Wendell Duplantis of the 3rd Battalion, 21st Regiment, Third Marine Division, issued simple orders. “We have to get that airfield today,” he said.

The Marines made a bold push for the airfield and, predictably, paid a heavy price. Leading their men forward at the run, officers fell quickly. Captain Rodney Heinze of Company K of 3/21 fell wounded from a grenade blast; Captain Clayton Rockmore of Company I of 3/21, lunging for a series of enemy pillboxes, was shot through the throat and killed instantly. Three lieutenants dropped in a storm of enemy fire, and command of the two companies devolved to sergeants.

Relief was on the way, in the form of First Lieutenant Raoul Archambault of 3/21, who had already earned Bronze and Silver Stars for heroism on Guam and Bougainville. He rallied the men and led them in a wild charge across the airfield. Although the two companies were badly shot up in the dash across the runways, they miraculously succeeded in reaching the far side and coming to grips with the Japanese on the northern perimeter of the airfield.

The enemy was well-positioned on high ground on the northern end of the field, and Archambault’s men pitched into them in a vicious hand-to-hand fight that ultimately cleared the trenches and pillboxes of Japanese. The breathless Marines regrouped and prepared for a counterattack; in a mere hour and a half, they had gained 800 yards of ground and seized Airfield No. 2.

As the battle for the northern reaches of the island commenced, such impressive gains in ground would be hard to come by. Schmidt’s plan called for his Marines to progressively drive north and, reaching the northern coast of the island, split Japanese defenses in two in the hope that remaining Japanese troops could be destroyed in detail.

Yet troops across the island faced increasingly forbidding terrain, and Marines would fall just to gain a few yards of rocky wasteland. One of the primary objectives was a Japanese defensive complex that lay in front of the 4th Division. Built around strongpoints that included high ground at Hill 382 and Turkey Knob, the ruins of Minami village, and a dangerous depression known as the Amphitheatre, the area would come to be known, and for good reason, as the “Meat Grinder.”

The first day of fighting at that location, on February 25, was indicative of what would follow. Determined to take the area with overwhelming strength, General Cates ordered both the 23rd and 24th Marine Regiments, numbering 3,800 men, to attack at midmorning. They ran into fierce opposition from Maj. Gen. Sadasues Senda’s 2nd Mixed Brigade, which would fiercely contest ownership of the Meat Grinder. A platoon of Marines succeeded in reaching the top of Hill 382 but was battered off the hill by a Japanese counterattack. After a full day of fighting, only one hundred yards had been gained by the two regiments.

Along the rest of the American line, progress was equally slow. The 5th Division on the west coast succeeded in overrunning the last two wells available to the Japanese. Desperate to regain access to the water, the Japanese launched an ill-coordinated frontal assault. Marines who were accustomed to rarely seeing the enemy in the open were delighted to watch as the Japanese attack was shattered by artillery fire.

Remarkably, another horrifying month of carnage awaited the men of both armies. Just 12 days after the initial landing, Japanese forces, initially numbering about 21,000 men, were down to approximately 7,000 men. By the first week of March, Kuribayashi moved his headquarters underground in remote terrain in the northwest corner of the island. As the Japanese were slowly pushed into an ever-tightening perimeter, they sold their lives dearly for every inch of ground gained by the Marines.

Despite heavy American casualties, General Schmidt slowly succeeded in tightening the noose around the island’s remaining defenders. Steady pressure on the defenses of the Meat Grinder, which was bolstered by armored support, finally succeeded in seizing the area after a week of bloody fighting. In that time, the Fourth Division had suffered 4,800 casualties but succeeded in capturing vital Japanese defenses at the Amphitheater, Turkey Knob, and Hill 382.

Exasperated by the heavy losses, General Erskine, to his credit, endeavored to exercise original thinking. Rather than continue to launch daytime attacks, which the Japanese had learned to expect, Erskine planned a nighttime assault on D+16 which, he hoped, would seize vital ground atop Hill 362C and break the impasse on the 3rd Division’s front.

The 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines, under the command of Lt. Col. Harold Boehm, succeeded at 5:00 a.m. in infiltrating Japanese lines, pushing 300 yards ahead in the darkness. A brief fight that caught the Japanese unprepared left Boehm in possession of a hilltop, which turned out to be Hill 331. A frustrated Boehm called in artillery support, and after several hours of further fighting, he succeeded in capturing Hill 362C.

For the Third Division, the hill was the last major obstacle in their drive toward the sea and splitting Japanese forces in half. On D+18, a patrol of 28 Marines led by Lieutenant Paul Connelly of the 1st Battalion, 21st Marines succeeded in breaking through to the coast. The remaining Japanese defenders, numbering just 1,500 men, were reduced to two isolated pockets on the northern and eastern corners of the island. Kuribayashi, hiding underground with what remained of his command, settled in for a final fight in the crags of a forbidding rocky gorge that the Marines nicknamed Death Valley.

There would be no final epic clash in the battle for Iwo Jima. To the very last, the Marines were forced to flush individual Japanese from their fighting positions with rifles, grenades, and flamethrowers. True to Kuribayashi’s initial plan, the bulk of Japanese troops fought to the death, extracting the highest price possible from the U.S. Marines sent to force them out. By the third week of March, the fighting was nearing a conclusion. A final message from the Japanese garrison went out over radio to a nearby Japanese naval base on March 23. “[To] all officers and men of Chichi Jima, goodbye from Iwo,” stated the announcement.

More senseless killing, though, would erupt in the early morning hours of March 26. Exhausted and hungry Japanese troops, far from disillusioned in their cause, were determined to die in the open rather than face death in the caves. Over the evening, upwards of three hundred Japanese infiltrated through American lines and then regrouped near Airfield No. 2. Before dawn, they launched a final, desperate banzai charge against an encampment of rear-echelon troops.

The surprise was total. In the darkness, a bloody melee erupted as Japanese troops stormed through the encampment, shooting and bayoneting confused Americans as they stumbled out of their beds. Nearby units rallied to halt the attack and pitched into the disorganized Japanese. By dawn the fighting was over. More than 50 Americans had been killed, as well as 262 of the enemy. Just 18 Japanese were captured.

The struggle for the island incurred a loss of life that was simply staggering, and Iwo Jima would remain the bloodiest battle in the history of the Marine Corps. All told, the V Amphibious Corps suffered 6,800 killed and 19,000 wounded. In the aftermath of the battle, 22 Marines and five sailors were awarded the Medal of Honor for gallantry at Iwo Jima. Of that number, 14 received their medals posthumously.

For the unfortunate Japanese troops stationed to Iwo Jima, the battle was a virtual death sentence. Kuribayashi’s forces had been annihilated. More than 18,000 Japanese troops are thought to have lost their lives. The Americans captured just 216 Japanese alive during the savage fighting.

Forever associated with the Marines, the struggle for Iwo Jima was recognized by observers as an epic moment in American history. “Among the Americans who served on Iwo Jima, uncommon valor was a common virtue,” said Admiral Chester Nimitz. Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, who had accompanied the American fleet off the island, recognized that the performance of common riflemen at Iwo Jima would ensure the longevity of a vital branch of the armed forces. “The raising of that flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next five hundred years,” said Forrestal.

Such lofty sentiments were likely lost on the Marines, who’d experienced the grinding horror of Iwo Jima. Jack Frazer, a corporal in the 2nd Battalion, 24th Marines, offered perhaps the most accurate assessment of the fighting on the island. The battle for control of the island lasted for five weeks, from February 19 to March 26. Scribbling in his diary on March 18, which was eight days before the mopping up ended, Frazer penned a brief but profound description of his own personal experience. “Iwo Jima is secured,” he wrote. “Twenty-seven days of hell.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments