By Chris Miskimon

Russia was imploding in October 1917. The war combined with the numerous internal stresses of the nation, culminating in a civil war and Russia’s withdrawal from the greater war. This created both opportunities and challenges for the German and Austro-Hungarian powers in the East. Although the defeat of Czarist Russia was a boon to the Central Powers, the East contained vast swaths of territory that would have to be secured by them to take full advantage of the Russian capitulation. Because of that, the German Army undertook a number of operations designed to place it in an advantageous position.

Operation Albion was the German land and naval operation in 1917 to occupy the West Estonian Archipelago. The operation aimed at the capture of three islands off the coast of Estonia: Hiiumaa, Muhu, and Saaremaa. Holding these islands would open a maritime invasion route to Petrograd and perhaps even all of Estonia from the sea. A fleet of 20 battleships and cruisers along with support vessels sailed into the area to prepare for a landing by General Ludwig von Estoff’s 42nd Infantry Division. The Russian 107th Infantry Division held the islands. Its troops had entrenched themselves admirably; however, desertions took their toll on the division.

The Germans sent zeppelins to pelt the Russian coastal batteries in advance of an invasion. One successful zeppelin attack destroyed a magazine and killed 107 Russians. Before the Germans could make an amphibious assault, the German Navy had to clear the waters around the islands of mines. Weather interfered significantly with this process. But the Germans launched their attack anyway because they feared that any protracted delay would doom the operation.

On October 12, 1917, German battleships approached Saaremaa, the largest of the three islands, to support a landing at Tagga Bay. A pair of battleships struck mines, but the fleet successfully silenced the shore batteries. German troops waded ashore against light resistance. The Germans pushed deep inland. The Russians on the island fought a delaying action and waited anxiously for reinforcements.

A brigade of German bicycle troops soon captured the causeway leading to Muhu Island. This cut off the Russians on Saaremaa. Russian destroyers tried to harry the German fleet and deploy additional mines but were largely unsuccessful in their efforts. Retreating Russian troops, many with their families, tried to leave the island, but the German bicycle troops drove them back. The Germans eventually ran low on ammunition and withdrew. At that point, some of the Russians made it over the causeway to safety. The Russians who escaped ran into the reinforcements and infected them with their panic. Many of the reinforcements fled as well.

The operation continued until October 20. By that point, Russian resistance had crumbled. The Russians simply could not stand up to the more disciplined and confident Germans. Although the fighting continued, it was clear to both sides that the Germans would emerge victorious. The Germans suffered approximately 400 casualties. Although it is difficult to precisely estimate the Russian casualties, their losses were staggering because the initial garrison had numbered 24,000. Most of the garrison troops on the archipelago were either killed, captured, or missing, although a small number escaped to the mainland.

The operation continued until October 20. By that point, Russian resistance had crumbled. The Russians simply could not stand up to the more disciplined and confident Germans. Although the fighting continued, it was clear to both sides that the Germans would emerge victorious. The Germans suffered approximately 400 casualties. Although it is difficult to precisely estimate the Russian casualties, their losses were staggering because the initial garrison had numbered 24,000. Most of the garrison troops on the archipelago were either killed, captured, or missing, although a small number escaped to the mainland.

The end of World War I in the East was a chaotic jumble of competing interests, independence movements, and desperate gambles. Nations tried to retain what they had and perhaps take useful territory from their opponents.

While the war in the West ground to a halt in late 1918, the fighting in the East continued for several years even though for Russia the Great War officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918. Fighting continued off and on for several more years. Territorial disputes existed that helped set the stage for World War II.

Many of these events are not well known in the West, but they are brought to light in The Splintered Empires: The Eastern Front 1917-21 (Prit Buttar, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2017, 480 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $30.00, hardcover).

This is the final work in the author’s four-volume history of World War I in Eastern Europe. The author ends on a high note, concluding the saga in an admirable fashion. Like the previous volumes, this book is chock full of the compelling stories that, when taken on the whole, give a comprehensive picture of the fighting. The author is an established authority on the Eastern Front in both world wars, and his depth of knowledge and ability to weave a coherent and interesting narrative shine through in the conclusion of this series.

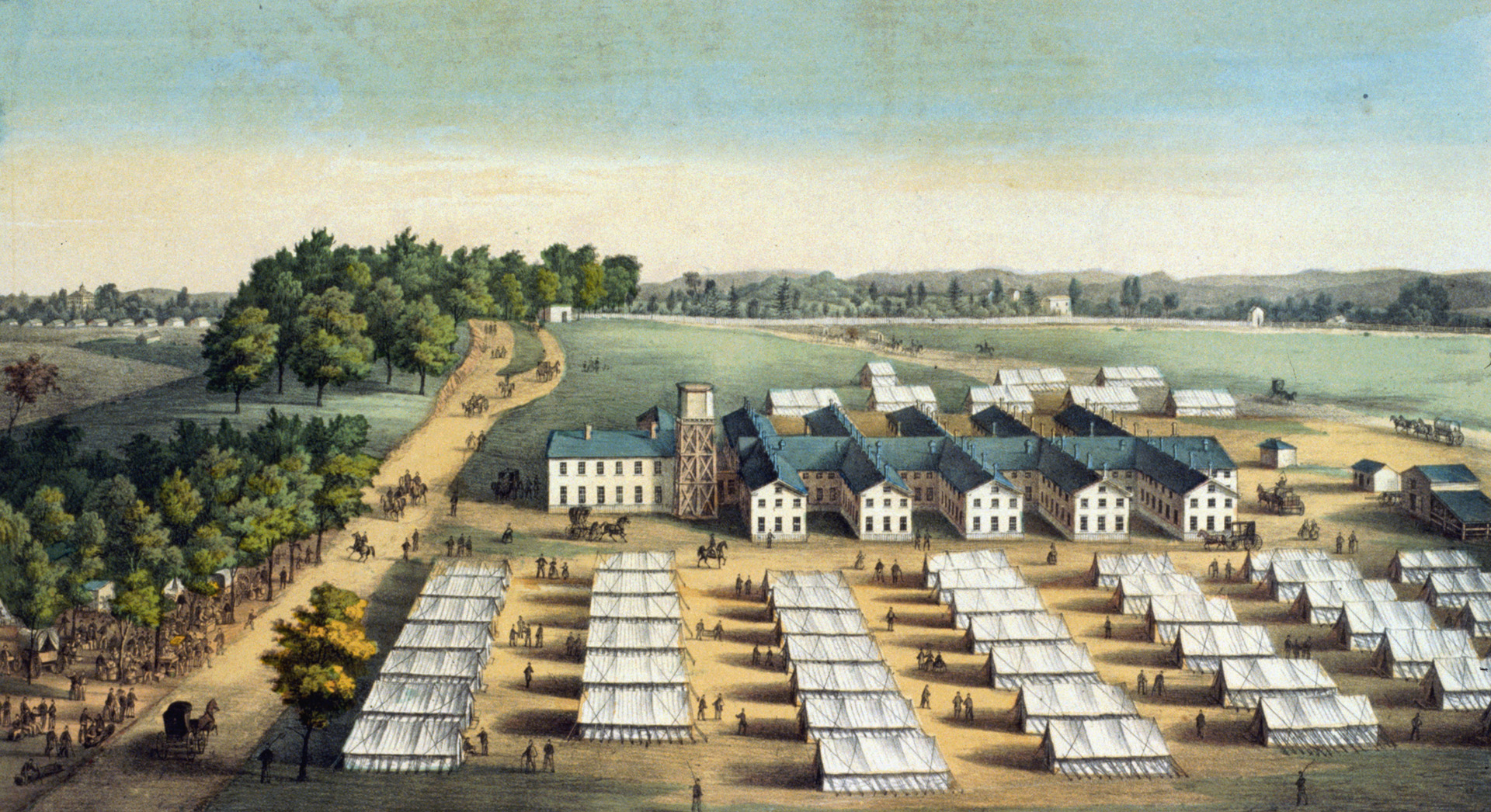

Grant (Ron Chernow, Penguin Press, New York, 2017, 1036 pp., maps, photo-graphs, notes, bibliography, index, $40.00, hardcover)

Grant (Ron Chernow, Penguin Press, New York, 2017, 1036 pp., maps, photo-graphs, notes, bibliography, index, $40.00, hardcover)

At the end of his life, Ulysses S. Grant, the great Union general and former president of the United States, sat pained by cancer, dictating his memoirs in a desperate bid to complete them before he died so that his family would not be left penniless.

It was a sad end for a great man who was hero to so many Americans, but his life had been plagued by such highs and lows. Since his death many have focused on those peaks and valleys. On the downside, he was a failed businessman, drunkard, and an inept politician. On the upside, he was the general most directly responsible for the Union victory over the Confederacy.

All things considered, his magnificent accomplishments seem undervalued. During the American Civil War he realized his potential. Grant was often derided as a butcher, but this seems deeply unfair. The Union suffered heavy casualties throughout the four years of the war, not just when Grant was in charge. He was the commander who recognized that victory would come at a high cost in lives, and he had the courage stay the course to achieve victory.

His two-term presidency was plagued with scandal, but he was not corrupt. Afterward, he was ruined financially by a swindler, but he dug his way out of penury by creating a memoir of more than 275,000 words in less than a year. What is more, he wrote his epic memoir while fighting cancer.

The author is a noted biographer with several prize-winning books to his credit. This work continues that tradition. He uses clear prose to make his subject come to life for the reader. The book is a well researched and engaging look at one of America’s greatest heroes.

The Bar Kokhba War ad 132-136: The Last Jewish Revolt Against Imperial Rome (Lindsay Powell, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2017, 96 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $24.00, index, softcover)

The Bar Kokhba War ad 132-136: The Last Jewish Revolt Against Imperial Rome (Lindsay Powell, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2017, 96 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $24.00, index, softcover)

In ad 132, a Jewish rebel leader named Shim’on ben Koseba assumed leadership of a restive Judean populace and led it into open revolt against the might of Imperial Rome. He assumed the name Shim’on bar Kokhba, which means “Son of a Star” and aimed to liberate Jerusalem and create an independent Jewish state. Ambushing Roman patrols from rooftops and hiding in caves scattered about the countryside, the Jewish fighters managed to resist the best Roman soldiers that Emperor Hadrian could muster for nearly four years. Eventually Roman determination and harshness overcame the resistance and the short-lived Jewish state was again brought under the Roman heel. The Jewish people suffered greatly during the war, enduring staggering casualties and seeing many of their towns and villages destroyed. The Romans even banned Jews from entering Jerusalem.

The Bar Kokhba War, which occurred six decades after the more famous Jewish revolt of ad 66-74, suffers from a lack of contemporary popular histories on the subject. This concise new edition fills that gap nicely. One of its strengths is its excellent visual aids for which the publisher is renowned. The author is an expert on ancient warfare, and he has succeeded marvelously in writing a book that brings to life the actions, participants, and effects of this ancient conflict.

Prisoners and Escape: Those Who Were There (Rachel Bilton, Pen and Sword, South Yorkshire, UK, 2017, 177 pp., photographs, index, $19.95, softcover)

Prisoners and Escape: Those Who Were There (Rachel Bilton, Pen and Sword, South Yorkshire, UK, 2017, 177 pp., photographs, index, $19.95, softcover)

On August 24, 1914, Harry Beaumont was near Mons, Belgium, when an artillery shell exploded nearby. It shattered a brick wall next to him. He slumped to the ground with a concussion and a slight wound. He lay where he fell for a full day before Belgian civilians found him and took him to a hospital. When Beaumont recovered from the concussion a week later, he learned that he was trapped behind enemy lines. The Germans had taken possession of the hospital.

Each day a German officer would check the prisoners and send those who were fit to Germany. Warned by Belgians as to when the officer planned to visit, Beaumont deftly avoided being in his bed each day. He eventually escaped. He and another wounded man moved from house to house with the assistance of sympathetic Belgians. In May 1915 he crossed the border into Holland and returned to England.

Beaumont’s story is one of 11 in the book. Each chapter contains one gripping tale and is recounted in the subject’s own words. Some of the tales do not have happy endings, though. The book includes photos and background information on each subject and also tells what happened to them afterward.

Hannibal’s Oath: The Life and Wars of Rome’s Greatest Enemy (John Prevas, Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2017, 336 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover)

Hannibal’s Oath: The Life and Wars of Rome’s Greatest Enemy (John Prevas, Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2017, 336 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover)

The spring flowers had barely bloomed when the great Carthaginian leader Hannibal set his army of more than 100,000 men and 37 elephants to march against the Roman Republic. From their starting point in Spain they would cross the Alps before they could descend upon the Italian peninsula and gain the vengeance they felt justified in taking. It was an arduous task that would cost thousands of lives, but it would secure Hannibal’s place as one of history’s greatest generals. Hannibal would defy Roman attempts to bring him low for years, despite the disadvantages of being on Rome’s home soil. Even today his skill, sense of strategy, and leadership abilities are studied and admired by soldier and scholar alike.

This latest biography of Carthage’s famed commander covers Hannibal’s life from his childhood, when legend says his father dipped his hand in blood and made him swear to be an enemy of Rome forever, to his death as an exile, when he chose to die rather than suffer the ignominy of captivity. The author combines information taken from the traditional sources with personal observations made as he visited many of the important places in Hannibal’s journey through life. Although Hannibal ultimately failed to conquer Rome, his story is worthy of retelling because of his astounding military victories.

Autumn of the Black Snake: The Creation of the U.S. Army and the Invasion That Opened the West (William Hogeland, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2017, 448 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover)

Autumn of the Black Snake: The Creation of the U.S. Army and the Invasion That Opened the West (William Hogeland, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2017, 448 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover)

The guns of the American Revolution had barely gone cold when the fledgling United States needed them again. Settlers were moving into the lands west of the Ohio River, an act they felt they had an absolute right to do. The Native American tribes in the area resisted these moves into what they believed was their territory and the stage for conflict was set. This led to an American rout at the Battle of the Wabash on November 4, 1791. A thousand American casualties were sustained in that engagement, the most ever suffered at the hands of Native American warriors. This compelled President George Washington to create a standing U.S. Army that would continue the campaign against the native tribes. The Northwest Indian War ended with the Battle of Fallen Timbers fought on August 20, 1794.

This new work sheds light on an important event in American history that has faded from popular memory. This was the closest a Native American force ever came to stopping the westward expansion of the United States. The author employs clear and engaging prose to pull the reader into a gripping period of American history. He identifies the errors and complexities both sides made. His work is a balanced one in that it describes the motivation of each side without making either side into a villain. Instead, he presents the story as one of competing peoples caught in an inevitable clash for control of a vast resource-rich land.

Airpower Applied: U.S., NATO and Israeli Combat Experience (Edited by John Andreas Olsen, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2017, 432 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $49.95, hardcover)

Airpower Applied: U.S., NATO and Israeli Combat Experience (Edited by John Andreas Olsen, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2017, 432 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $49.95, hardcover)

The U.S. Air Force delivered 9,500 troops to Panama in less than 36 hours during Operation Just Cause in December 1989. The refueling tankers that supported the aerial bridge came from 23 squadrons that transferred 860,000 gallons of fuel per day. Cargo planes carried more than 20,650 tons of supplies. C-130s dropped Rangers on Rio Hato airfield while F-117 fighters supported them. While there was a friendly fire incident at Rio Hato, the support from the stealth fighters helped them seize the airfield by demoralizing the Panamanian defenders. AC-130 gunships fired on Panamanian positions alongside Army attack helicopters.

When Manuel Noriega finally surrendered, U.S. troops put him into a Special Forces MC-130 to be returned to the United States for trial. The invasion succeeded in large part due to this complex weave of air support, transport, and cargo operations.

The history of airpower is full of examples, not all of them success stories. This new work analyzes a number of separate air campaigns from World War II to the present. For each campaign, the author gives a concise summary of the event and the factors that contributed to it. He also analyzes the effectiveness of each air campaign in achieving its desired goals. Last but not least, the work examines how airpower can be used in a way that is consistent with political objectives.

Curse on This Country: The Rebellious Army of Imperial Japan (Danny Orbach, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 2017, 384 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover)

Curse on This Country: The Rebellious Army of Imperial Japan (Danny Orbach, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 2017, 384 pp., notes, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover)

The soldiers of the Japanese Empire went into World War II with a reputation for being automatons who were blindly obedient to orders and slavishly loyal to the emperor. While this may have some truth for the common soldier who was inculcated with obedience as a cultural and military imperative, the leadership was more inclined to disobey the Japanese government. There were numerous instances of military officers staging coup d’états, including one against the emperor when he tried to end World War II. Japanese officers often initiated military operations in spite of orders to the contrary, such as in China in the 1930s. Assassinations also occurred. The result was a decades-long journey for Japan as it slowly succumbed to fascism and suffered defeat in a global war.

Japan’s descent into military madness is closely chronicled in this detailed study. It begins with Japan’s chaotic rise into the contemporary modern world during the late 1800s and follows its imperialistic rise, which extended into the 20th century. It uses primary source material from five languages. The author weaves a compelling narrative of Japan’s road to both victory and defeat in World War II.

Marked for Death: The First War in the Air (James Hamilton-Paterson, Pegasus Books, New York, 2016, 384 pp., photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $$27.95, hardcover)

Marked for Death: The First War in the Air (James Hamilton-Paterson, Pegasus Books, New York, 2016, 384 pp., photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $$27.95, hardcover)

The first war fought in the air was almost a death sentence for those who battled in it. World War I pilots had a 70 percent casualty rate, the equal of even the hard-pressed infantrymen of the time. Despite these odds, there was never a shortage of men willing to go aloft and take on their counterparts in aerial duels.

Aircraft were a new invention, only a decade old and far from a mature technology. Aircrews died in accidents and through malfunctioning equipment as much as by enemy bullets. The risk was worth it to them. They were doing things no one had done before, creating a legacy that would endure through to the 21st century. It was dangerous, thrilling, brutal, and glorious to flyers of the era. Those who survived came home as heroes of a new age, and those who died in aerial combat received top honors.

A quote from aircraft designer and pilot Anthony Fokker serves as the title of this new work. It referenced the peril every pilot voluntarily put himself in when he went aloft. The author does a superb job of bringing to life both the thrill and the terror of being a World War I combat pilot. The author includes many journal entries and other writings from pilots of the period. The firsthand accounts enable the reader to know the thoughts and fears of these brave airmen. The work charts the progression of air power from the start of the war to the final armistice.

Short Bursts

WRNS: The Women’s Royal Naval Service (Neil R. Storey, Shire Books, 2017, $14.00, softcover) This concise history of the Wrens, as they were known, shows both their origin in World War I and their expansion during World War II.

WRNS: The Women’s Royal Naval Service (Neil R. Storey, Shire Books, 2017, $14.00, softcover) This concise history of the Wrens, as they were known, shows both their origin in World War I and their expansion during World War II.

The Sharpshooters: A History of the Ninth New Jersey Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War (Edward G. Longacre, Potomac Books, 2017, $34.95, hardcover) This regiment took part in 42 battles in three states. After its initial enlistment expired, the entire unit re-enlisted for the duration of the war.

Shoot Like a Girl: One Woman’s Dramatic Fight in Afghanistan and on the Home Front (Mary Jennings Hegar, New American Library, 2017, $26.00, hardcover) Hegar was an Air National Guard helicopter pilot. She was shot down on her third tour there and later fought to enable women to serve in combat units.

The Ambulance Drivers: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and a Friendship Made and Lost in War (James McGrath Morris, Da Capo Press, 2017, $27.00, hardcover) Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos both drove ambulancess during the Great War. Each would go on to write novels about the war from his own perspective.

American Journalists in the Great War: Rewriting the Rules of Reporting (Chris Dubbs, University of Nebraska Press, 2017, $34.95, hardcover) This is the story of how American reporters covered World War I in Europe. Their articles, reports, and personal anecdotes are all included.

Going Deep: John Philip Holland and the Invention of the Attack Submarine (Lawrence Goldstone, Pegasus Books, 2017, $27.95, hardcover) Holland was a brilliant, self-taught inventor. After decades of effort, he succeeded in creating an effective submarine design.

Going Deep: John Philip Holland and the Invention of the Attack Submarine (Lawrence Goldstone, Pegasus Books, 2017, $27.95, hardcover) Holland was a brilliant, self-taught inventor. After decades of effort, he succeeded in creating an effective submarine design.

Viking Warrior versus Anglo-Saxon Warrior: England 865-1066 (Gareth Williams, Osprey Publishing, 2017, $20.00, softcover) These two warrior groups clashed for centuries, fighting for control of England. This book summarizes their tactics, weapons, and battles.

The Leader’s Bookshelf (Adm. James Stavridis, USN (Ret.) and R. Manning Ancell, Naval Institute Press, 2017, $29.95, hardcover) This book reveals the reading libraries of more than 200 four-star generals and admirals. They are presented as works used to learn the art of leadership in war.

Democracy and the American Civil War (Edited by Kevin Adams and Leonne Hudson, Kent State University Press, 2016, $24.95, softcover) This book contains five essays discussing race, equality, and democracy during the war and in its aftermath.

The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End (Robert Gerwarth, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017, $28.00, hardcover) The author maintains that November 11, 1918, was a meaningless date because for many around the world fighting continued without pause.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments