By David H. Lippman

Another invasion also began on June 6, 1944. By virtue of the International Date Line, the two invasions sailed on different days, but both sortied within the same 24-hour period. One invasion involved 127,000 U.S. soldiers and Marines and 535 ships and landing craft. The second invasion had 10 times that number: the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. (Read more about the events that shaped both European and Pacific Theaters inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

Instead of heading for Normandy in France, this “other” invasion was headed farther, along a 10-day voyage from Hawaii and other bases to Saipan, an island 1,200 nautical miles from Tokyo, 12 miles long and 46.5 square miles in area. Once taken, it would provide the U.S. Army Air Forces with a base for the huge Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers to pound Tokyo. Also up for invasion in the same attack were Saipan’s neighbors, Tinian, and a small piece of American soil that had been violated since Pearl Harbor, the island of Guam, under Japanese occupation for three long years.

Seizing the Northern Marianas would thus redeem American honor. It would also signal to Japan that the Empire’s main defense line had been breached and force the Combined Fleet to emerge from two years of hibernation and training to fight the decisive battle against the Americans to save that Empire—the biggest carrier battle yet fought and one of the most decisive naval battles in history.

A New Generation of Ships and Planes

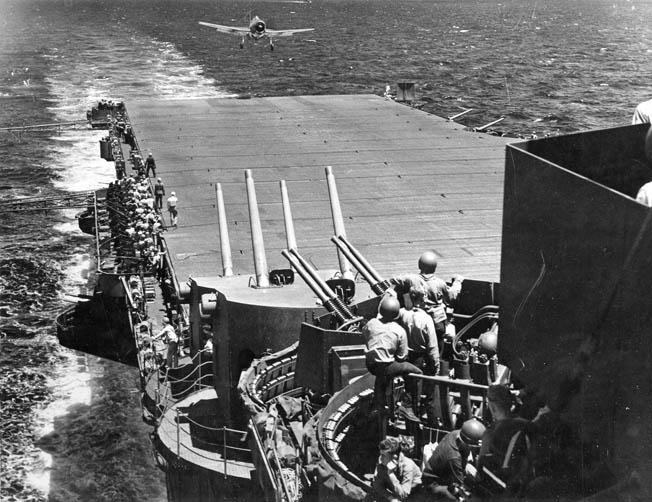

By 1944, the American counterattack against Japan’s aggression was in full flood. The losses at Pearl Harbor and thereafter had been made good with what was virtually a new navy and air force, and a series of invasions had taken the Gilbert and Marshall Islands from the Japanese.

Indeed it was a new navy. Of the 15 carriers lined up at Majuro Atoll under Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, only one predated Pearl Harbor—the venerable USS Enterprise, with a battle record unmatched in nearly any navy. The battleships, cruisers, and destroyers that escorted “Murderers’ Row” were also relatively new, fast ships that bristled with antiaircraft guns and electronics unheard of before the war.

The aircraft were from a new generation as well, powerful Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers and massive Grumman F6F Hellcat and Vought F4U Corsair fighters, which could run rings around Japan’s Zeros with their powerful engines. The ships’ very names showed America’s resilience. Four of the aircraft carriers, Lexington, Hornet, Wasp, and Yorktown, all bore the names of American carriers sunk in 1942.

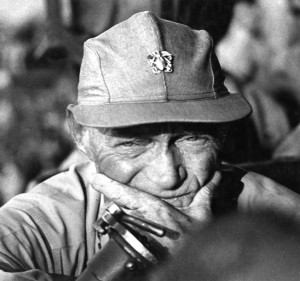

Yet the old ships were still there—one of them, the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis, known to her crew as the “Indy Maru,” doubled as Spruance’s flagship. The battleships that endured bombing at Hawaii were back as well, too slow to form the primary battle line but loaded with high explosive shells for shore bombardment. Spruance’s 5th Fleet was a huge organization, but at its core was Task Force 58, under Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher, flying his flag on the Lexington. Mitscher commanded 15 fleet and light carriers, seven fast battleships, 12 escort carriers, 11 cruisers, and 91 destroyer escorts. Covering this force were nearly 900 aircraft.

Spruance, the boss of the entire 5th Fleet, was no aviator, but he had already won the greatest air-naval battle of them all, America’s incredible victory at Midway. Cool, quiet, described as a “patient fox,” he used caution to plot the deadly Midway ambush. Now he was leading a huge fleet on a massive offensive on Saipan, Tinian, and Guam.

Ozawa’s Powerful Naval Force

He may have known it from radio intercepts and codebreaking, but Spruance gave no inkling that he was interested in the fact that the commander of the Japanese garrison on Saipan was an old enemy, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who had led the attack on Pearl Harbor and been defeated at Midway.

But Nagumo was not leading Japan’s naval riposte to the American invasion, now steaming down on Saipan. That job was in the hands of Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, regarded as the Empire’s best carrier admiral. Commanding the Mobile Fleet, his situation was becoming increasingly critical. While the U.S. Navy grew in strength, his navy was slowly being whittled away. Japanese dockyards and training schools could not keep up with American industry and technical skill. American submarines, having overcome torpedo deficiencies, were cleaning the seas of Japanese tankers, strangling the homeland and denying the Imperial Navy vital fuel.

To fight the battle, the Imperial Navy had moved the carrier force to Singapore, close to its oil stocks in Java and Borneo. The Borneo crude oil was of such high quality that it could be pumped straight into the Imperial Navy’s bunkers without refining. However, the unrefined sulfur-ridden Borneo crude could damage the Navy’s pipes, and more importantly, was even more flammable than the refined variety.

None of this mattered to Ozawa. His brief was to defeat the Americans, and even if that meant his ships would all have to get major engine repairs after the battle, he would fight hard with what he had. The plan was called Operation A-Go, and it was activated shortly after the U.S. Fleet arrived off Saipan on June 8, to start softening up the island.

Operation A-Go called for the Japanese to hit the Americans with everything they had as soon as the American objective had been determined and destroy the enemy with one blow. To do so, the Japanese had some high cards to play. First were Ozawa’s eight carriers, which included his flagship, the powerful new Taiho, a 34,000-ton behemoth, the largest carrier afloat and Japan’s first with an armored flight deck. She carried 60 aircraft.

Behind her were the last two veterans of Pearl Harbor, Shokaku and Zuikaku, sisters at 29,800 tons each, carrying 80 aircraft apiece. Behind these three tough warriors were two smaller carriers, the Hiyo and Junyo, both converted liners weighing 26,949 tons, carrying 53 aircraft each. With four more light carriers, Chitose, Chiyoda, Zuiho, and Ryuho, Ozawa could sortie 450 aircraft—much fewer than his American counterpart, but still the largest carrier-based air force Japan would ever deploy.

Ozawa also had 540 land-based aircraft scattered on airfields across the Pacific with orders to concentrate on Saipan and the Marianas. He also had something new for Japan, giman-shi, or deceiving paper, better known to the British as “window” and the Americans as “chaff,” metallic paper that would jam American radar screens.

The planes were also tough, if outdated. The main fighter was still the Mitsubishi A6M5 Zero, while the primary torpedo bombers were the older B5N Kate from the Pearl Harbor glory days and the newer B6N Jill, both from Nakajima. The dive-bomber of choice was the modern Yokosuka D4Y1 Judy, which sported retractable landing gear and a Daimler-Benz engine, backed up by the venerable Aichi D3A1 Val. One fatal weakness was evident. While American aviators had up to 400 hours flying time, some Japanese pilots had as little as 20 in their logbooks.

Behind the Japanese carriers came a powerful force: the two of the largest battleships ever built, Yamato and Musashi, equipped with nine 18-inch guns each; the slower Nagato, with 15-inch guns; and the powerful and fast battleships Haruna and Kongo. Seven heavy cruisers and one light cruiser backed up the dreadnoughts, along with 19 destroyers.

Smashing Saipan, Tinian, and Guam

The key to the Japanese plan was the 500-odd aircraft on its ground bases, which would attack the Americans initially and whittle down their air umbrella, enabling the surface ships and carriers to punch out the American carriers and battleships, leaving the American transport fleet open to attack.

The American invasion of the Marianas would require their fleets to sail as far as 1,017 miles from their anchorage at Eniwetok, and as far as 3,500 from Hawaii. More than 535 ships loaded with 127,571 troops sortied from a variety of ports, with the assault set for June 15. The invasion was code-named Forager.

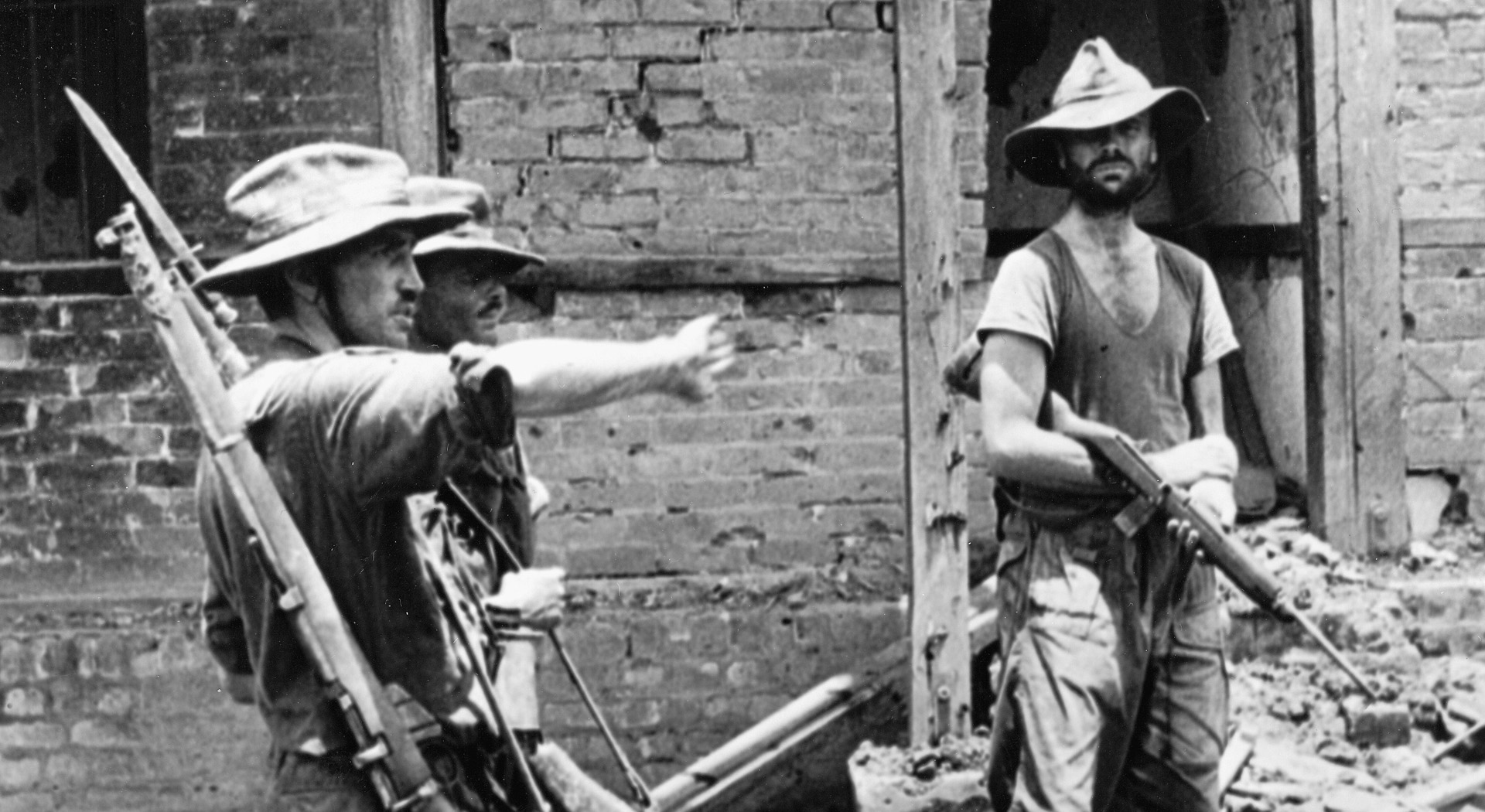

Nagumo’s defenses were formidable. The 21st Army, under Lt. Gen. Yoshitsugu Saito, fielded about 31,629 men which included 6,690 Navy men, including a tough 800-man Special Naval Landing Force regiment and naval guard force of 400 men. They were equipped with eight Whitworth-Armstrong 6-inch guns, nine 140mm guns, eight 120mm guns, four 200mm mortars, and a collection of bunkers, pillboxes, and machine guns.

Task Force 58 sailed from Majuro at Eniwetok in early June amid a steady drizzle. Under the gray skies, 96,618 men crewing 111 U.S. warships painted in dazzle camouflage steamed from the anchorage at two-minute intervals. It took the whole task force five hours to sortie and shuffle into antisubmarine formation. Behind them came the bombardment forces and transports.

On June 11, the 15 American carriers got to work pulverizing the Japanese defenses, hurling more than 200 fighters and torpedo bombers against Saipan and Tinian. The senior American carrier air unit was CVG-10, based on USS Enterprise. Under its ebullient boss, Commander William R. “Killer” Kane, CVG-10 was a well-trained veteran outfit, which included a night-fighting group of F4U Corsairs. That day Kane led 58 Hellcats against Saipan.

Kane nailed one of two Zeros and Lieutenant (j.g.) Alfred Taddeo got the other one. Killer spotted another Zero above and shot that one down, too, with a single well-sighted burst. Taddeo spotted a big Japanese four-engine Kawanishi reconnaissance plane and filled it full of .50-caliber bullets. Some 36 Japanese planes fell on or over Saipan.

Over Guam, the Hornet’s VF-2 had good hunting too, getting into a dogfight with an estimated 30 Zeros. Two F6Fs and two Zeros closed on each other at a combined 500 mph, but VF-2’s skipper, Commander William A. Dean and Lieutenant (j.g.) David R. Park each flamed their enemy. Then Dean spotted another Japanese fighter, closed in and shot the Zero down in flames. He pulled back on his throttle and shot down another Zero, becoming VF-2’s first ace.

Also entering battle over Guam was VF-15, the “Fabled Fifteen,” part of CVG-15 from USS Essex, led by Commander David McCampbell, famed for his flying ability and movie-star looks. In its first dogfight, VF-15 splashed nine Japanese planes. The Americans claimed nearly 100 kills for 11 losses, but three of the Americans were pulled from the drink. Actual kills over Guam amounted to 98 (American sources) or 22 (Japanese sources). The following day, the Americans resumed pounding the islands, splashing 22 more Japanese planes over Guam. Enterprise launched 169 sorties that dropped 52 tons of bombs.

American planes spotted a convoy of 12 merchant ships loaded with reinforcements for Saipan 160 miles away. The Americans hit it twice on the 12th and again on the 13th. In two days, the Americans disposed of a torpedo boat, three sub-chasers, and 10 of the merchant ships for a total of more than 30,000 tons.

Meanwhile, the Americans continued their attacks on Saipan, Tinian, and Guam, hammering the Japanese airfields. By D-day on the 15th, the Japanese air force on the three islands was reduced to nothing.

Tracking Fleet Movements

On the 11th, Ozawa ordered his ships to sea from Singapore, to fuel at Tawi Tawi, and then to engage the Americans. The Japanese were spotted on the 13th by the submarine USS Redfin.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy’s old battleships and cruisers took on Saipan’s gun emplacements. Their first bombardment, on June 13, was accomplished by the seven fast battleships, which had not trained on shore bombardment, and was a failure. On June 14, the more skilled slow battle wagons steamed in, having trained at the Kahoolawe gunnery range under Admiral Jesse Oldendorf. The battleships Maryland, Pennsylvania, California, and Tennessee represented the victims of Pearl Harbor, and the Colorado, New Mexico, Mississippi, and Idaho made up the rest of the force. Six heavy cruisers, five light cruisers, and 26 destroyers added to the din.

Nagumo peered through a telescope on shore to watch with chagrin as the ships he had bombed and damaged at Pearl Harbor exacted revenge, blasting open his defenses. Later he would commit hara-kiri in despair.

The Japanese shot back. “The nerve of them!” said a bluejacket on the cruiser Honolulu. They scored hits from a single 4.7-inch field battery in a cave mouth on California, one killed, nine wounded; the destroyer Braine, three killed, 15 wounded; and Tennessee, eight killed and 26 wounded. All three ships stayed in battle.

On June 15, the huge landing force faced heavy opposition on Saipan. Thirteen Japanese planes were downed, seven to the light carrier San Jacinto’s air group alone. After dark, Japanese planes were spotted, but the night squadron VF (N)-76, operating from Enterprise, chased them off.

Ozawa’s force steadily advanced, watched by American submarines. Late that afternoon, the USS Flying Fish caught the Japanese exiting San Bernardino Strait. Seahorse saw them off the Surigao Strait. The Americans ordered more submarines to intercept, among them the brand new USS Albacore on her first patrol.

On June 16, some 54 American planes hammered Iwo Jima’s defenses, bombing and strafing 60 aircraft on the field. On Saipan, Marines fought hard to drive inland against ferocious defenses. Japanese snoopers kept an eye on Task Force 58.

Two Reconnaissance Phases

American submarines continued to dog Ozawa’s moves. Commander Herman Kossler’s USS Cavalla spotted Ozawa’s tankers that night on radar and tried to attack, but the Japanese escorts chased him away. Kossler headed back in and found a group of 15 ships. June 17 came, and Kossler closed the range on his radar targets.

On Taiho, Ozawa planned his battle. He would hit the Americans with the aircraft from his light carriers first, holding his heavy carriers back for the second wave. Ozawa was confident that because of Spruance’s conservative nature the Americans would stay within 100 miles of the invasion beaches. Both sides were squaring to outflank each other but did not know it.

After church services ended on Sunday, June 18, Task Force 58 began launching scouts to find Ozawa. Simultaneously, Ozawa launched his scout planes. The fleets were 420 miles apart, beyond the American search radius, but within Japanese range. All day long the scouts prowled the Pacific.

Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet stayed undetected, but the Japanese were able to locate the Americans when Scout Number 17 found three carrier groups 180 miles west-northwest of Guam. On June 19, both sides would launch carrier strikes, and Ozawa would use his superior aircraft range to keep his force out of the American torpedo bombers’ sights. He changed course from northeast to southwest to open the range.

Meanwhile, ground-based Japanese divebombers hit American Task Group 50.17, a group of oilers. They damaged three, losing three raiders to flak. American fighters shot down 23 of the 31 Japanese planes in this opening skirmish.

Studying the situation, Spruance realized that his massive force could not close the range to sink the Japanese carriers, so he would fight a defensive battle. His ships would absorb the Japanese attack and whittle down the enemy airpower with fighters and flak. Then, once the Japanese had lost their air umbrella, Spruance would counterattack—if possible.

The Origin of the Term “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot”

Before dawn on June 19, both sides’ carriers signaled “Flight Quarters,” and scout planes departed on their missions. The Japanese had learned the lessons of Midway and would send out a two-phased search system. The first wave of Japanese scouts did poorly: only six of 15 returned. At 5:15, 14 more reconnaissance planes leaped off Ozawa’s decks and catapults—to find nothing. An irritated Ozawa launched 43 more reconnaissance planes.

On the other side, the Americans headed east, into the morning wind as the sun rose at 4:30 am. At 5:15, the Americans picked out their first bogies, and the carriers scrambled their F6F combat air patrols. The first kill of the air massacre that came to be known as the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot went to Lieutenant (j.g.) Walter T. Fitzpatrick and his USS Monterey division, which shot down two Judy scout bombers 30 miles west of their ship.

The American plan for the day, assuming there was no carrier battle, was to hit Guam, and they did so while their scouts went to work. By 7 am, the American combat air patrol (CAP) had splashed 10 Japanese scouts from Ozawa’s first-phase search.

Ozawa’s second-phase team did better, finding some of Vice Admiral Willis A. “Ching” Lee’s destroyer screen, but at 7:30 a Jake floatplane, heading back from the limit of its range, spotted an American carrier group and Ching Lee’s fast battleships and fired off an accurate report.

Combat Information Center: Spotting the Japanese Air Attack

Ozawa planned to take advantage of his long range. His planes would strike the Americans and then either return to his carriers or to the bases on Guam or Saipan to refuel. From there, they could attack the Americans again and return to his carriers. Between 8:30 am and 11:30, Ozawa’s carriers launched 326 aircraft in three groups at Mitscher’s carriers. Then Ozawa turned south.

The lead Japanese group, “Raid I” to the American radar plotters, was 69 planes from the three light carriers Chitose, Chiyoda, and Zuiho: 45 Zero fighter bombers, 16 Zero fighter escorts, and eight Jill torpedo planes. Organized as Air Group 653, the planes headed east with orders to attack the Americans and then return home or to Guam, depending on their fuel situation.

Another American advantage in battle was about to be manifested for the first time: the Combat Information Center, a dark room that glowed with light from radar tubes and crayoned letters on glass plotting boards—one of the few compartments on a warship that had air conditioning because of its lack of portholes and other ventilation. The CIC enabled radar plotters, air defense directors, gunnery officers, and admirals to plot battles in a swift, organized, comprehensive manner. As the Japanese planes advanced toward their targets, they were picked up by American radar, and plotters wrote in the information on the Plexiglas screens (writing backwards and in reverse) so that the brass hats could make the right decisions.

The first Japanese raid showed up on those boards at about 10 am, 150 miles away. On the carrier flight decks, signal flags snapped the diamond-design “Fox” flag, which meant “Commence flight operations.”

By 10:23, the carriers had turned into the wind and were launching planes. While the F6Fs formed up into four-plane divisions, the rest of the fleet went to general quarters. When the Japanese were 60 miles out, they tidied up their formation and regrouped stragglers. At that point, the American fighters attacked, with half an hour to go before the Japanese were in range of the American ships—more than enough time.

Eight Hellcats from USS Essex’s VF-15, under Commander Charles W. Brewer, slammed into the Japanese first. Brewer and his wingman, Ensign Richard E. Fowler, quickly downed four planes apiece. Lieutenant (j.g.) George R. Carr, a Floridian with Royal Canadian Air Force experience, shot down two Jills before a Zero came after him. Carr shoved his stick full forward into a headlong dive, then pulled out at nearly 500 mph, turned to the right, losing the slower-moving Zero. Carr saw another Zero heading right for him. Both sides fired, but only Carr scored hits, setting the Zero on fire. As it flamed, Carr saw yet another Zero and opened fire, tearing off the Zero’s wing. Then Carr split-essed to line up a finishing shot, and the Zero exploded. Carr recorded five kills during his first U.S. mission.

In a few minutes, VF-15 had claimed 20 kills.

Six more squadrons charged in, ripping holes in the Japanese formation. Commander Ronald W. Hoel of VF-8 from Bunker Hill was saved when his wingman shot down an attacker. Next came VF-2 from Hornet, whose eight Hellcats claimed nine Zeros and three Jills. Then came Princeton’s shark-mouthed Hellcats storming up at the Japanese from below. Lieutenant Fred Bardshar gunned down a bomber, then a second.

The Japanese scored only a single hit against Lee’s battleships, a solo shot on USS South Dakota, which had a reputation as an unlucky ship. The 500-pound bomb hit her first superstructure deck and killed 27 of the crew, blasting a large hole in the ship. Wiring and piping were damaged, a 40mm gun knocked out, and the captain’s and admiral’s quarters damaged. But South Dakota maintained course and speed, shooting down two enemy planes within minutes of the hit.

The Japanese lost 42 of their 60-odd planes for the loss of three Hellcats. Not one Japanese plane reached the American carriers. It was a textbook example of fleet air defense.

The Japanese claimed hits on a large aircraft carrier and a large cruiser. Ozawa’s second wave, Air Group 601, launched at 9 am with 128 planes—53 Judy dive-bombers, 27 Jill torpedo bombers, and 48 Zero escorts—from the big carriers. This group included planes armed with giman-shi.

After forming up over Taiho, Shokaku, and Zuikaku, they flew toward the Americans and took antiaircraft fire from their own ships. Friendly fire knocked down two Japanese planes and forced eight to abort. As the survivors hurtled on, Ozawa ordered his last two carriers, Hiyo and Junyo, to launch Air Group 652, some 47 additional planes, in the third raid.

Explosion on the Japanese Flagship

While the carriers secured from flight quarters, the Americans began their counterattack, starting with their smallest weapon, USS Albacore, the brand new attack submarine. Commander Blanchard had kept his submarine fixed on the Japanese fleet and finally got a dream attack. A Japanese carrier group appeared right before his periscope and target data computer (TDC). He let one carrier pass, then set up his shot two miles from the next carrier. Just as Blanchard was ready to fire, the TDC broke down. Blanchard stayed on his periscope and set up a visual solution. Six torpedoes raced toward the carrier.

As Blanchard took his submarine deep, he told his men to brace for depth charges. They heard and felt plenty—two dozen rattled Albacore but did not damage her. The last torpedo scored a hit.

The unlucky carrier was the new Taiho, and she was nearly saved. Warrant Officer Sakio Komatsu had just been launched on the second raid. He saw a torpedo heading toward his flagship and dived right on it, killing himself, his observer, and the American fish. But one of the other five struck home, flooding the forward elevator well. Water gushed in, drooping the bow down four feet, knocking the elevator down six feet, and putting the flight deck temporarily out of commission.

Work crews broke out two-by-fours and laid planks over the elevator hole, patching it up within half an hour. Reassured his flagship was operational, Ozawa stayed aboard. Nobody noticed that the torpedo had sliced open an aviation fuel storage tank, which leaked into the flooded elevator well.

Worried about accumulated gasoline vapors, a damage control officer on Taiho ordered the carrier’s ventilation system opened to dissipate the fumes. Instead, the unstable Borneo crude oil vapors spread throughout the carrier.

It only took four hours for the inevitable to happen. At about 3:30 pm, Japan’s newest carrier exploded. An interior blast sent the flight deck buckling upward, and the huge carrier blazed, slowly sinking by the head. Ozawa, on the bridge, stared down at the wreckage and said he would die with the flagship. However, he was later convinced not to go down with the carrier and shifted his colors and command to the destroyer Wakatsuki.

Sinking the Shokaku

Three hours after Albacore’s torpedoes hit Taiho, Herman Kossler aboard Cavalla spotted a carrier group. Not knowing where Mitscher was, Kossler needed to positively identify the contact. He and his executive officer and torpedo officer pored over recognition charts.

Kossler looked through his scope again and finally got what he needed. He saw the Japanese flag flying from the carrier’s signal block. “There was the rising sun, big as hell,” he said later. It was Shokaku.

Kossler slammed down his scope and used radar to plot a course to fire six torpedoes at the carrier. Cavalla’s TDC worked perfectly, and all six tubes fired from 1,200 yards at eight-second intervals. Torpedoes raced toward Shokaku. After the fifth fish launched, Cavalla began diving. Shokaku went hard to starboard, seeking to comb the spread of torpedoes so that they would pass on her sides, but it was too late. Four torpedoes slammed home. They blasted holes forward to amidships near the aviation fuel tanks, which were in use refueling aircraft.

An aviation gas main and its unstable Borneo crude exploded, showering burning gasoline onto the flight deck, which also blew the forward elevator nearly three feet up. Then the elevator collapsed into its well, killing men below. The carrier began listing to starboard.

Captain Hiroshi Matsubara ordered counterflooding to port, but the damage control men overdid it. Soon Shokaku was listing to port. For four hours, the great carrier burned. At 3 pm a bomb exploded, setting off fuel vapors trapped on the hangar deck. A terrific explosion resulted, and the carrier began to sink, water flooding her forward elevator well. In minutes, the big ship stood vertically on her bows, and then Shokaku disappeared, taking with her 1,263 men, including 376 from Air Group 609.

Thirty Miles of Air Combat

The second raid was now approaching the Americans. Some 53 dive-bombers and 27 torpedo bombers swarmed in behind the giman-shi. USS Lexington’s radar picked up the Japanese at 11:07 am. Once again, the Japanese regrouped before heading in, giving the Americans time to scramble their fighters. McCampbell’s Essex aviators got there first, 72 miles out, at 11:39 am, an hour after the first raid had ended.

This battle was fought over a 30-mile space for several minutes. The Essex fighters jumped on the Japanese with four Hellcats tying up the Zero top cover and McCampbell taking his other six planes into the Judys, shredding five almost immediately. The rest of VF-15 charged in, bagging nine more bombers and five Zeros. American pilots watched as Japanese planes spiraled into the ocean, but the Japanese regrouped and kept flying in. The Americans sent in 43 more F6Fs from Lexington.

Meanwhile, Lexington’s fighters went to work, with Lieutenant (j.g.) Alex Vraciu, an ace with 12 kills, seeing a “once-in-a-lifetime fighter pilot’s dream.” Vraciu swooped in and flamed a Japanese bomber. Then he spotted two more and blasted them both. Three kills. Another Judy broke formation, and Vraciu fired .50-caliber rounds “right into the sweet spot at the root of his wing tanks.” The plane fell, burning, into the ocean.

As the Japanese entered the American flak zone, Vraciu chased three more Judys. He lined one up, opened fire, and the nearest Judy exploded—then another one. The third one, trying to flee, flew into American flak and exploded. Vraciu had six kills in eight minutes, giving him a total of 18. He headed back to Lexington, where he smiled for photographers, holding up six fingers for his wild eight minutes. He finished the war with 19 kills.

The Japanese Lock Onto the American Carriers

Meanwhile, the battle raged on. Next up was Yorktown’s VF-1, which piled in with 13 F6Fs, claiming eight kills. Ensign Cyrus R. Garman was shot down, and Lieutenant William C. Moseley could not make it back to the Yorktown in his damaged Hellcat, so he landed on the Hornet. After Moseley exited gratefully, the maintenance men studied his battered airplane, decided it was finished, and hurled the wreck over the side.

The Bataan air group was next in the parade, and her F6Fs had the longest trip to the battle area, answering the fighter director’s message: “Your signal: Buster.” That meant Bataan’s aviators had to go full throttle, and they charged in, among the last aircraft on the scene.

Despite appalling losses, the Japanese flew on with samurai bravery, nearing the American battleships by 11:45 am. The Japanese bombers began swooping down on the battleships—two Jills went for South Dakota and were shot down by Alabama. Another turned kamikaze and splattered into the hull of USS Indiana, but to no avail—its torpedo was not armed. Another dive-bomber missed Alabama.

Only six Japanese bombers passed up the battle wagons in favor of the carriers, and they pressed in on Task Group 58.2 and USS Wasp, arriving at high noon. Wasp spotted the Japanese 10 miles off the starboard bow. When the Japanese passed by, Wasp’s gunners thought the planes were American, but suddenly one peeled off and dived. The Americans opened up, but the Japanese plane dropped a phosphorous bomb, which went off over the flight deck, killing one sailor and injuring 12. Then the Japanese plane exploded.

Meanwhile, other Japanese planes slipped through the defense. Two Judys headed for Bunker Hill and managed to drop bombs that killed 76 Americans and damaged the carrier’s portside elevator. Even so, Bunker Hill’s damage control team kept the ship in action.

Fighting 10 from Enterprise took on the Japanese over Task Group 58.3 amid shell fragments and blazing aircraft. Six more Judys headed for Enterprise and Princeton, and the American carriers maneuvered to avoid bombs and torpedoes. A Judy swooped in on Enterprise’s starboard quarter at 3,000 feet, dropped its bomb at 1,500 feet, pulled up, and was blasted apart. The bomb missed.

At 12:03, Japanese torpedo planes finally were able to release their deadly loads. Enterprise was the primary target, which annoyed her veteran crew. The torpedoes missed, and when a second group of Jills flew in, hammering antiaircraft guns shredded the attackers. Only one torpedo headed for Enterprise, exploding in the carrier’s wake, causing no damage. Enterprise’s 40mm guns had splashed two Jills and her 5-inchers a third.

Princeton was last to be attacked, facing three torpedo planes, and her Captain William Buracker relied on maneuvering and antiaircraft fire to avoid his enemies.

80 Raiders killed

Last up, oddly enough, was the Taiho’s giman-shi plane, which released its chaff and pulled 14 Cowpens fighters from the inbound strike to attack the tinfoil. They found the flying metal paper and the plane dropping it, but the D4Y Judy escaped its attackers.

And then it was all over, after six minutes of heavy antiaircraft fire, with the radar operators reporting the survivors fleeing. Monterey’s fighters were sent to attack the retreating bandits, and Lt. Cmdr. Roger Mehle, a decorated veteran of Midway, led his fighters in. They tagged six Jills and a Zero. Two went to Mehle.

Then the fighters all headed home, pilots eager to tell their stories of victories. Task Force 58 had sent 162 fighters to cope with 119 raiders. The Americans claimed 80 kills. Of the 119 raiders, a bare 31 returned to Guam or the surviving Japanese carriers. Twenty-three of the 27 Jills were shot down (85 percent), 42 of 53 Judys (79 percent), and 32 of 48 Zeros (66 percent).

The 20 Japanese planes that returned to their carriers reported damage to three American carriers and 25 kills. In actuality, they had done moderate damage to Bunker Hill, slight damage to Wasp, and the armor belt impact to Indiana. American air losses were a mere four planes and three pilots.

The victory was crushing, but the battle was far from over. The third raid was hurtling in with 47 planes—just seven torpedo planes, 15 Zero fighters, and the rest Zero fighter bombers—coming from the light carriers. They were to hit the American carriers but got lost. American radar operators and fighter directors watched their screens with amazement as the Japanese wandered around, finally coming into range of Task Group 58.1.

USS Hornet shot off eight F6Fs and Yorktown four more, joining 12 from Langley. They found the Japanese 50 miles away and jumped straight in. It took the Americans only minutes to splash nine Japanese planes. At 1:20, a gaggle of Zero bombers pushed through the fighter cordon and attacked Essex. Only one pilot reached attack distance, but his bomb fell 600 yards away from the carrier. Two American pilots, Lieutenant (j.g.) Jerome D. Keyser and his wingman, both from Langley, bracketed the Japanese pilot, and Keyser flamed him.

Raid three was yet another failure, but the Japanese were not done yet. Carrier Division Two hurled 27 Val dive-bombers, nine Judys, 10 Zero bombers, and 18 escorts. They hooked up with 14 Zero fighters from Zuikaku and six Jill orphans from Taiho. Eighty-four planes would make up the second largest Japanese strike of the day. Orders were to attack the Americans, then land on Guam. However, with U.S. troops invading that island the orders meant they should make kamikaze attacks on the Americans on shore.

Zenji Abe’s Attack Run

The Japanese planes thundered down the flight decks, seamen standing by, waving their white caps, as they had at Pearl Harbor. Leading the bombers from Junyo was a Pearl Harbor and Midway veteran, Lieutenant Zenji Abe. He had not flown for 40 days and felt rusty. As his planes flew on, two element leaders had to return home when their landing gear would not fold up. A Zero developed engine trouble. A dive-bomber and three fighters disappeared. Abe recalled that he “wondered whether they retired … due to mechanical trouble or dove into the sea from mental confusion.”

Abe reached the intercept point and found only ocean. He swooped low beneath the clouds and realized that his briefing information was faulty. He played a hunch and headed northeast. Sure enough, Task Force 58 turned up at 10 o’clock low, all turning to starboard with huge wakes. Abe ordered his men to attack.

As Abe’s pilots swooped in, Monterey’s radar picked them out, but the fighter director could not contact his own pilots. He called Wasp. For once, the American response was not rapid. Abe’s planes closed to within 50 miles of the carrier group. An hour after the Japanese were spotted, American interceptors from Monterey and Wasp finally plunged into battle. Wasp’s Fighting 14 punched out two Zeke bombers and a Jill, but it was too late—a Japanese attack was actually going to hit its target in strength.

Abe swung in on Bunker Hill and came under heavy antiaircraft fire. “That was dreadful for me,” he remembered. The flak did not knock down too many planes, but it did spoil their aim. Abe dropped his bomb, pulled out, and headed away.

The bombing accuracy was not good. Three bombs splashed into the ocean near Bunker Hill, but the carrier’s maneuvering sent one of her F6Fs and its plane captain (or chief mechanic) over the side and into the drink. The plane captain was rescued.

Finally, the antiaircraft gunners got the range and splashed one Judy, then ripped the tail off another, then caught a Judy just after dropping its bomb and both fell into the sea. A Japanese plane crashed so close to Wasp that four men of a 20mm gun were knocked off their feet.

Near-misses cascaded water all over Wasp, drenching her crewmen on weather decks. A phosphorous bomb went off 300 yards above the carrier’s deck but only wounded one sailor—the ship’s sole casualty. Then the Japanese pulled out, with Abe hitting the firewall on his engine, gulping fuel. There was not enough to head for Guam or his carrier, Junyo, so he steered back to nearby Rota.

The Pacific War’s Largest Air Battle Concludes

Ozawa now knew that regardless of the battle’s outcome he was out of planes and running short of flight decks. At 5 pm, he shifted his flag to the heavy cruiser Haguro, which at least offered an operations room and flag space, and tried to figure out what was going on. As he reached the cruiser’s bridge, everyone heard a low, rumbling sound. Taiho’s battered hull was giving up the ghost at last and going to the bottom 2,500 fathoms below with 660 of her men, 13 planes, and the only coding machine that could handle Ozawa’s high-priority traffic. He would have to use the low-level coding machines on Haguro, which the Americans could read, for the rest of the day.

The Carrier Division Two squadrons that got lost from Abe’s group were told to head for Guam but to get rid of their ammunition before doing so. Cowpens’ radar picked out about 50 Japanese planes circling Orote Field on Guam, preparing to land. Cowpens hurled 41 Hellcats into attack, and they shot down 30 of the Japanese planes and damaged another 19 beyond repair, some as they landed on the cratered runway.

Suddenly, the greatest air battle of the Pacific War was over. All the American radar screens went clear, and the American planes, gulping gas, ammo trays empty, began circling their carriers to land. It was time to start counting casualties and planning new moves.

314 Japanese Planes Lost

The first portion was a staggeringly one-sided assessment. The U.S. forces had lost a mere 31 planes, 21 of them Hellcats, and sustained minor damage to Bunker Hill, Wasp, South Dakota, Indiana, and the heavy cruiser Minneapolis. Some 30 Americans had been killed.

The Japanese had lost two carriers to submarines. Out of 373 planes hurled into battle, a bare 130 had returned to the remaining Japanese carrier decks or islands. By day’s end, Ozawa had only 102 operational planes of the 450 he had sailed with. And 50 more shore-based planes had been destroyed. It was one of the most one-sided air battles in the history of warfare—314 Japanese planes and most of their pilots lost.

But the Philippine Sea battle was not yet over. While American airmen and antiaircraft gunners celebrated victory with secret liquor stashes and debriefings, their bosses planned the continued destruction of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

On the Japanese side, Ozawa had to figure out what to do. The Americans were still heading east, being sure to stay far away from his battleships and cruisers. Tokyo ordered Ozawa to keep attacking, working with land-based air units. Ozawa, however, was more realistic. He ordered his ships to take a northwest course, away from the Americans and toward his refueling tankers. Battleship boss Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita recommended complete withdrawal. Ozawa, knowing Kurita’s tendency toward timidity, ignored the suggestion.

Mitscher’s Task Force 58 turned west, ready to attack as long as the ground battle on Saipan was not jeopardized, but the Americans were still not used to night flying, so they held off launching scouts until the 20th at 5:30 am.

The Japanese were observing strict radio silence, so there were no transmissions to home in on. It would take the Americans until 4 pm to find their enemies. Once again, the Japanese had the weather gauge, and Mitscher had to steam east to launch his aircraft.

Finding the Japanese Fleet

As the day and the search planes droned along on both sides, Japanese Jake reconnaissance planes hooked up in battle with F6Fs on the same mission, which led to three splashed Jakes, and the Americans believing that a damaged Japanese carrier was near the search planes. On Lexington, Commander Gus Widhelm suggested to Spruance that 12 Hellcats, lugging 500-pound bombs, could fly to the limit of their 475-mile range, and sink the reported cripple. Mitscher mulled the idea over and suggested they take along an Avenger torpedo bomber to handle navigation and provide radar support. Commander Ernest Snowden, who led Lexington’s fighters, called for volunteers, telling his aviators, “Chances are less than 50-50 you’ll get back.” He wrote down 12 numbers for slots on the big blackboard and put himself down in the top spot. Thirty minutes later, all 12 slots had been taken.

Snowden and his teammates, escorted by eight F6Fs from San Jacinto, headed out on the longest carrier-based search of the war to date.

The Japanese had been busy, too, regrouping their battered fleet. With two carriers lost, Ozawa switched to the Zuikaku around 1 pm and started learning just how horrific was the previous day’s casualty bill, but an optimistic message from Guam led Ozawa to believe he still had land-based planes and the battle could still be won.

Meanwhile, the rest of Task Force 58’s search planes ranged on. Enterprise sent out four search teams, and at 3:30 pm. Lieutenant (j.g.) Robert R. Jones’s team spotted what the U.S. carriers had been seeking for the past two years, Japan’s carriers at sea, their wakes frothing. The scouts reported the location, and on the American carriers pilots and navigators pulled out their navigation boards and wrote down the courses to answer the message: “Enemy fleet sighted. Latitude 15-00, longitude 135-24. Course 270, speed 20.”

“We Can Make it, But it’s Going to be Tight”

Japanese radio monitors picked up the American transmissions, and Ozawa cranked up his speed to 24 knots to get away from the Americans.

On Lexington, Widhelm and Mitscher stared down at their maps and plotting tables. Time was short before dusk. At length, Widhelm said, “We can make it, but it’s going to be tight.” Mitscher merely said, “Launch ‘em.”

A late afternoon full-deck load air strike was a hefty thing to launch, and the distance to target was 230 miles and increasing. Pilots manned their planes at 4:10 pm, and within minutes 240 aircraft were warmed up and ready to fly, all bearing 115 tons of ordnance, either bombs or torpedoes.

Launch commenced at 4:24. Of the 240 planes launched, 14 aborted, but 95 Hellcats, 54 Avengers, and 77 dive-bombers, 26 of them Douglas SBD Dauntlesses, were en route to pummel the Japanese. The big carriers provided most of the bombers while the light carriers provided the fighters. The airmen averaged 24 years of age with extremes of 19 to 43. Lexington’s 57 aviators alone represented 25 of the Union’s 48 states.

Once the planes were up, Mitscher began to worry that his planes and pilots might not get home by dark. He ordered his brilliant chief of staff, Rear Admiral Arleigh Burke, to work out a plan for illuminating the task force to assist homing pilots in the dark.

The planes roared along into the sun, working to conserve fuel, on course 290. Fighter escorts flew in lazy S-turns to avoid outrunning their bombers. At 260 miles, they spotted the first enemy ships, three of Ozawa’s oilers. The Wasp’s air group pounced on them and sank two right away, Seiyo Maru and Genyo Maru. The carriers were 35 miles beyond the oilers, partially hidden beneath scudding clouds.

The Americans knew they had to attack immediately, and so did the Japanese. Ozawa had scrambled 40 Zero fighters for combat air patrol, and 28 fighter bombers, along with six Vals. It was a good number of aircraft, but not enough against the Americans.

Helldivers Against the Zuikaku

First to feel the teeth of American dive bombing was the weakened Carrier Division One, down to Zuikaku. Bugles blared on the Japanese ships, and antiaircraft guns opened up as bombers from Hornet, Yorktown, and Bataan plunged down on the Japanese carrier.

Lieutenant Harold E. Buell of Hornet swooped down to 6,000 feet, then placed the dive-brake selector back to “open,” and the wing brakes did just that, even though the manufacturing specifications on his Helldiver said they could not. No matter, at the point-blank range of 2,000 feet Buell dropped his payload and simultaneously took a heavy-caliber round that set his starboard wing afire and put a shell splinter in his back. Buell punched the fire extinguisher button, pulled his plane out of the dive, and began heading for home.

Dive-bombers and torpedo bombers pounded Zuikaku. The big carrier gushed smoke, and the next wave figured Zuikaku was doomed and left the blazing carrier alone, seeking other prey. Eight Zuikaku Zero pilots found themselves without a home and had to ditch in the water.

On Zuikaku’s flag bridge, Ozawa studied the Americans with professional interest. He was impressed by their valor but unnerved when strafing fighters wounded a staff officer with a .50-caliber round.

Zuikaku was luckier than her sisters. She dodged two torpedoes and took a lot of near-misses, but one hit split open her aviation fuel system and covered the hangar deck with 80-octane aviation fuel, which promptly cooked off. Zuikaku had recently installed a foam firefighting system like the American carriers, but it did not work. Captain Takeo Kaizuka ordered his men to abandon ship, but nobody below got the word. Instead they reported back upstairs that they were getting the fire under control. Kaizuka belayed his original order, and Zuikaku was saved.

Not saved were most of her remaining airmen, who had few places to go. One pilot had flown off Hiyo the day before, landed on Taiho, high-lined to a destroyer, then to Zuikaku, and now had to recover his plane aboard the light carrier Ryuho.

Assault on Carrier Division Two

Carrier Division Two, with Hiyo, Junyo, and Ryuho, also took it in the teeth, with Enterprise, Lexington, and San Jacinto air groups pounding them. Lieutenant Charles W. Nelson led his torpedo bombers against Ryuho, dropping his fish at 1,000 yards. The Japanese antiaircraft guns riddled his Avenger with automatic fire, and Nelson and his crew crashed fatally. Ryuho evaded all five torpedoes flung at her.

Another group was led by Lexington’s Lt. Cmdr. Ralph Weymouth, a Guadalcanal veteran who had flown off the Saratoga. At age 27, he was an old timer. Assessing the targets, he attacked the Hiyo, escorted by Alex Vraciu’s Hellcats. Japanese fighters charged through clouds to take Vraciu’s planes by surprise, knocking down Lieutenant (j.g.) Warren E. McLellan’s TBF before Vraciu realized he was under attack.

Three Hellcats faced eight Zero fighters, but Vraciu was an ace and immediately shot down a Zero that in turn was shooting down his wingman, Ensign Homer W. Brockmeyer. The wingman’s plane spiraled toward the sea, and Vraciu tried to follow him. But two Zeros came in, and Vraciu had to shoot down one of them and lost track of Brockmeyer.

Meanwhile, the Avengers fought off the angry Zeros. McLellan himself was lucky—he and his crew bailed out of their cripple and were able to splash into the drink safely, where they inflated their raft and Mae West jackets. The young Arkansan pondered the great distance between his location and home as the sun began to set.

Torpedo 16 from Lexington fought back against their attackers. AMM1c Jack W. Webb in Lieutenant Norman A. Sterrie’s Avenger shot down a Zero that got too close, earning Webb a Distinguished Flying Cross for his accurate gunnery. The Japanese were determined, but not too effective—three SBDs were hit by Japanese gunfire but not damaged severely.

At 7:04 pm, VB-16, the Minutemen, plunged in on Hiyo, dropping 1,000- and 500-pound bombs on the converted liner. Weymouth had scored a near-miss on Hiyo’s sister, Junyo, two years ago at the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. Weymouth plunged down to 1,500 feet and hit the red button atop his stick. He and his crew looked back as they pulled out to see a smoke puff erupt beside the carrier’s island.

Other Lexington pilots roared down on the two carriers, finding Hiyo obscured by clouds but Junyo easy to see. Lieutenant Cook Cleland, a cheery Ohioan with three Air Medals and a Purple Heart, flew his SBD Dauntless through heavy flak, taking shell hits, and scored a hit on Junyo just forward of the carrier’s stern. As he pulled out, a Zero leaped at them. Gunner William J. Hisler opened fire with his .30-caliber Browning and put 60 rounds into the Zero’s bottom. The Japanese plane spun off, trailing smoke, dropped a wheel, and ditched near a destroyer.

Lexington’s airmen claimed seven half-ton hits on both carriers, but Hiyo took one bomb hit and Junyo two from all the attackers. Fading light, noise, youthful excitement, and high speed, as usual, counted for exaggerated claims.

Next up was Enterprise’s group, and they poured into the three carriers with determination and near-vertical attacks. Commander Jim Ramage led his planes in on Ryuho’s bow, but his bomb missed, dropping in the ship’s wake. As it exploded, shaking Ramage’s plane, a Zero stormed in. Ramage pulled out. Three of Ramage’s other five pilots dropped close aboard; one claimed a minor hit.

Four VT-10 Avengers also went after Ryuho with fighters covering the approach. Heavy flak from the veteran battleship Nagato and Ryuho herself filled the air, but the TBFs from the Buzzard Brigade dropped their torpedoes anyway. They claimed eight hits. The Japanese reported slight damage from near misses.

San Jacinto had bad luck, too. Lt. Cmdr. Donald J. Melvin could not release his torpedoes. He pulled up from his target, Hiyo, and tried again, this time on a destroyer, and claimed a hit. He was wrong.

Three Carriers Lost

Belleau Wood’s group showed ample determination, with Lieutenant George Brown splitting his torpedo bombing division into an anvil attack on Hiyo, which worked perfectly. The Japanese carrier had nowhere to go to avoid incoming torpedo bombers, but Brown himself paid for the attack. His plane was hit, and while his two crewmen were able to escape, Brown was trapped in the burning aircraft, last seen struggling to bring his crippled plane back home.

Two torpedoes hit Hiyo’s starboard quarter, and the carrier was torn open and began flooding, her steering gear wrecked. Hiyo was fatally damaged.

Carrier Division Three, Chitose, Chiyoda, and Zuiho, faced Bunker Hill, Cabot, and Monterey. Bunker Hill’s Bombing 8 took on Chiyoda and claimed six hits on the carrier and three more on two escorts. In actuality, the carrier took two hits, which killed 20 men and wrecked two planes, but Chiyoda stayed in business.

VT-31 from Cabot went after the legendary battleship Haruna. One bomb hit the battleship’s aft turret, killing 15 men and threatening a magazine. Captain Shigenaga Katazuke flooded the magazine, and the battle wagon kept station.

Torpedo 8 came in next, to hit Chiyoda, and Captain Eiichiro Joh went hard to starboard, putting his stern to the attackers, and escaped the torpedoes.

Eight minutes after the attack began, it was over. The Americans, having expended their ordnance loads and ammo, began pulling out. Incredibly, the Japanese thought they had been attacked by 140 to 150 aircraft, when the Americans had sent in twice that number.

All eyes were on the blazing Hiyo, where explosions were tearing her apart steadily. It took her only six minutes to go to the bottom. Destroyers rescued 1,000 men, and 250 went down with the ship.

The other carriers were not in much better shape. Zuikaku was damaged by a bomb hit, Junyo by two near the smokestack, which utterly crushed it. Chiyoda had taken a hit on her after flight deck, and Haruna took two hits that left her hull warped and a magazine flooded. Junyo would survive, but her battle damage took her out of the war. She would be found relatively intact at Sasebo on V-J Day. Two oilers had been sunk, and 19 more planes had been lost.

Ozawa was stunned. He had now lost three carriers, three more were damaged, and most of his planes were gone. The decisive battle for the Empire was turning into a decisive disaster.

Recovering the Returning Aviators

But now, as the sun set, the 209 planes of the American strike force had to find their way home in the dark, to blacked-out carriers. And the Americans were at the edge of their range, short on fuel. As they headed back on course 090, they began splashing into the sea. To make flying worse, it was the first night of a new moon, with no moonlight.

By 8:15, the radar operators on the American carriers had their planes, mostly gaggling to the west. At 8:30, Mitscher’s carriers turned into the easterly wind to prepare to recover planes.

There was little controversy on Mitscher’s flag bridge. The planes had to be recovered. At 8:30, Mitscher gave the order, “Turn on the lights!” As Burke had planned, the fleet went on full illumination: powerful searchlights from the carriers, starshells rocketing high from cruisers, destroyers aiming their searchlights at the flattops. The pilots were amazed, delighted—and confused. They did not need to see every ship in the task force, just their carriers.

Discipline broke down as the gulping planes returned. Pilots slapped their fuel-exhausted machines on the first decks they could find. Sometimes two or three planes tried to land at once. Even so, some 70 carrier planes went into the drink, most of them from Wasp.

The pilots who ditched faced grim ordeals. Wasp bomber leader Commander Jack Blitch ditched 25 miles from the nearest searchlight, passing out during the crash. He regained consciousness underwater in a closed cockpit. He did not remember getting out, but found himself standing on the plane’s sinking wing, searching for his absent gunner. He was just able to haul his life raft out of the plane. Blitch spent the next 40 hours waiting for pickup, hauled in by a floatplane from the cruiser USS Canberra, named for the Australian capital and cruiser lost at Savo Island.

One of Blitch’s subordinates made his landing on Enterprise. It was his first night “trap.” Other pilots who splashed in the water near the carriers rejoiced at the fact that the American radars watched them go down, and destroyers raced over to rescue them, lights blazing.

Enterprise’s night-fighter detachment of Chance-Vought F4U Corsairs helped out, too, with the radar-equipped planes searching through the sky for loose and lost aircraft and guiding them home. Pilots did not bother with standard call-signs or jargon. Wearied from long flights, they left gun switches on and tried to land in twos and threes.

Torpedo 24’s Lieutenant (j.g.) Warren Omark landed on the carrier Lexington instead of his own Belleau Wood. He and his crewmen bent down and kissed the flight deck anyway. They were down to two gallons in their tanks. For two hours recovery operations continued.

A plane crashed on Enterprise’s deck, forcing her lost planes to land on other carriers. An F6F ignored a wave-off signal and slammed onto Yorktown’s deck anyway, wrecking another F6F on the deck and killing the pilot, Lieutenant (j.g.) M.M. Thomme, Jr. Yorktown had to douse its lights and stop recovery operations while the flight deck crews cleared the wreckage.

Three Monterey planes had landed when Ensign R.W. “Pappy” Burnett’s Avenger swooped in, damaged by Chiyoda’s flak. After three failed attempts to find a clear deck, Burnett’s engine quit, out of fuel, and the plane ditched. The crew escaped onto the wing, pushing their three-man raft out, and just got into it as the plane sank into the ocean. Fortunately, the destroyer Owen had its searchlight on them the whole time.

The Navy’s Lead Ace Touches Down

Alex Vraciu, who had scored so many kills that day, also landed on the wrong carrier, Enterprise, with only drops of fuel to spare.

Eventually the sun rose, and the Americans counted the cost: out of 226 planes launched, 146 had been recovered. Some 172 pilots and aircrew were missing. Immediately the fleet went on search-and-rescue missions, finding numerous exhausted pilots. Some 90 were hauled in during the night. Orbiting aircraft hunted for the mirror flashes, yellow dye, and rubber rafts that denoted missing pilots, but it was tough. A Hellcat’s one-man raft was difficult to spot on that slate gray sea.

Even so, Task Force 58 claimed 67 kills. Vraciu himself was up to 19, which would make him the leading Navy ace for another three months. The Japanese pilots would not come back—their planes lacked self-sealing fuel tanks and armor, and their air-rescue system was rudimentary compared to the comprehensive American plans.

Three Japanese Carriers Lost

Meanwhile, the Japanese coped with yet another round of disaster. Hiyo was going down. The crew found time to remove the Emperor’s portrait from the bridge and the battle flag, and survivors mustered on the flight deck in an orderly manner to abandon ship and sing the usual battle songs. Captain Toshiyuki Yokoi made sure his men went over the side, saluting each in turn. Then he sat down on an empty ammo box and waited to die, 126 days after taking command.

At 7:26 pm, the inevitable combination of lethal gasoline vapors from the unstable Borneo crude and 80-octane aviation fuel ignited within the carrier’s hull, and Hiyo’s bulkheads began to collapse, sending Yokoi and Hiyo’s 20,000 tons to the bottom of the Pacific. The Mobile Fleet had lost three fleet carriers in less than 30 hours. The Japanese were whipped. They headed for home.

Task Force 58 was whipped, too, but with the fatigue of victory and a very hard day and night. Crewmen cut loose from flight and general quarters collapsed in their bunks, in corners, passageways, wherever they could find a little sleep. Those who could or had to stay awake worked to get the lost and stray pilots back to their home ships or toss damaged aircraft over the side.

Some of the aviators wanted to make one more strike on the Japanese, but Spruance vetoed that. He saw the Japanese had lost all their planes and were retreating. At the same time, he had no idea of what the actual Japanese casualty bill was. As far as he knew, all three carriers actually sunk were still afloat.

Spruance always made his decisions on the side of caution. His job was to protect the invasion of Saipan, and the Marines needed air cover. At 8:30 that evening, Spruance called off any pursuit. Except for picking up the missing aviators, the Battle of the Philippine Sea was over.

“Utterly Awakened From the Dream of Victory”

The Japanese reported for a certainty that they had sunk or damaged four or five carriers and a battleship or large cruiser, and made 160 kills. In actuality, the Americans lost no ships and 42 aircraft. American dead: 14 pilots killed in combat, 13 over Guam and on searches, 31 sailors killed on the ships in the airstrikes. With the difficult recovery operations on the 20th, it added up to 76 American fliers dead.

The defeat was catastrophic for the Empire: three carriers, 476 planes, and 445 pilots and airmen killed. Total sailors might never be figured out: between 2,000 and 3,000 went down with their sunken carriers, on top of the 445 dead airmen.

The American reaction was also harsh. Spruance was blamed by his superiors for not finishing off the crippled Japanese fleet, noting that headlines such as “375 Jap Planes Killed” did not play as well back home as headlines that said “Jap Fleet Sunk.” Aviators complained that the more aggressive Halsey would have pursued the Japanese and sunk all their ships.

Just as important, the U.S. Navy had demonstrated for the first time its absolute mastery of aero-naval warfare. Spruance’s fleet took very little damage at the hands of the Japanese and showed the ability to coordinate massive forces to achieve crushing victory for little loss. Even the planes lost to mishaps and the night landings were easily replaced, and few of the pilots and airmen were lost. The U.S. Navy had demonstrated how to wage modern naval war. Every other navy in the world, including the vaunted Royal Navy, would follow the American lead.

Lastly, the defeat of the Imperial Navy broke the back of the Japanese strategy to defend the homeland. A month after the Marianas disaster, Japan’s Prime Minister, Hideki Tojo—the architect for and scapegoat of Japan’s failed policies—was forced to resign. For the first time, the Japanese general staff recognized that its nation was losing the war, and the Empire faced two choices: destruction or surrender.

The coda was left to a defeated Japanese admiral, Matome Ugaki, who commanded Japan’s battleships at Philippine Sea. He wrote some poetry in his diary on June 21:

“Utterly awakened from the dream of victory,

Found the sky rainy and gloomy.

Rainy clouds will not clear up,

My heart is the same

When the time for the battle’s up.”

While this articles recognize that 535 ships of all types were involved in Operation Forager, I have yet to read a commentary that recognizes and compares the commitment of all US combat ships over 1,000 tons with that made by the IJN. The disparity was even more massive than usually depicted: The US navy fielded seven fleet carriers, eight light fleet carriers, sixteen escort carriers (including four transporting aircraft replacements, or destined for captured airfields), fourteen battleships, twelve 8″ cruisers, eighteen 6″ cruisers, one hundred and ten destroyers, nineteen destroyer escorts and about 1,500 aircraft, transported on all 31 carriers. In comparison the IJN fielded five fleet carriers, four light fleet carriers, five battleships, thirteen 8″ cruisers, four 6″ cruisers, twenty seven destroyers, plus about 750 aircraft, including 450 carrier based and 300 land based.