By John Walker

It was just after 3 am on Saturday, July 30, 1864. A month of relative quiet along a two-mile stretch of Union and Confederate trench lines immediately east of Petersburg, Virginia, was about to come to an explosive end. In the aftermath of several earlier Federal attacks on the strategically vital city in mid-June, a portion of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps picket line lay only 400 feet from Elliot’s Salient, a highly fortified position on high ground that formed an angle protruding out from the main Confederate line, commanded by Maj. Gen. Bushrod Rust Johnson.

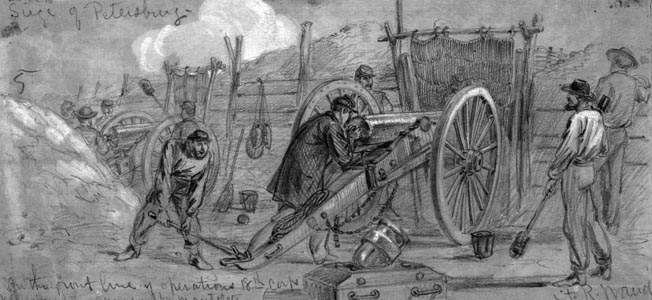

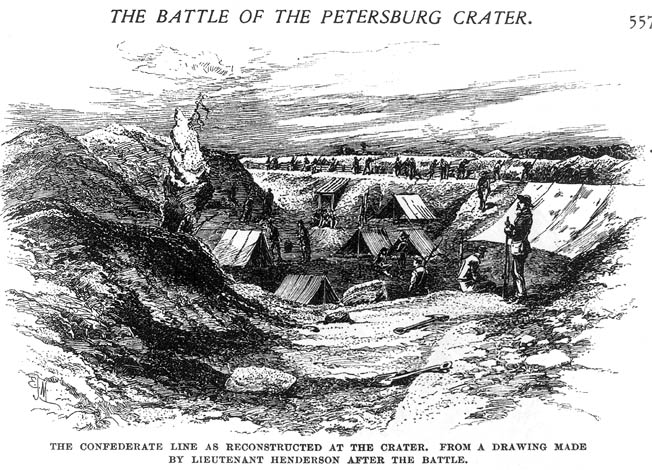

To support the defenders’ artillery and mortars, a second line, or “cavalier trench,” had been dug close behind the main redoubt. Elliot’s Salient boasted four smoothbores of Lt. Col. William Pegram’s battery and was backed by two regiments of veteran infantrymen of Brig. Gen. Stephen Elliot’s South Carolina Brigade. Across a north-south ravine from Elliot’s Salient were trenches occupied by the troops of Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants’ 48th Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment, many of them coal miners in civilian life.

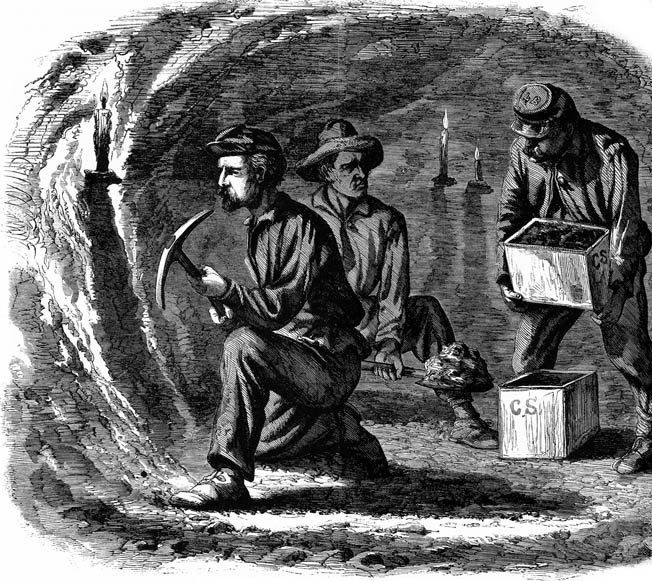

In an unprecedented feat of excavation, and after coming up with the idea on their own, the men of Pleasants’ regiment dug a 511-foot-long tunnel right up to the Rebel works, 20 feet underground, and packed it with 8,000 pounds of highly explosive black gunpowder. After the mine was exploded at 3:30 am and a concentrated Union artillery barrage hit the two-mile stretch of Rebel works, a massive assault by 14,000 Union troops was planned to exploit the expected breach blown in the enemy’s line. If the Federals could swarm past the ruptured strongpoint and take the high ground 500 yards behind it, where Blandford Church’s cemetery was located, the city of Petersburg, terminus of four railroads and Richmond’s crucial lifeline to the Deep South, could be captured before the day was done. With Petersburg in Union hands, the Confederate capital of Richmond would surely soon fall as well. After a series of Union thrusts against Petersburg—flanking movements rather than costly frontal assaults—from June 9 to June 24 had failed and General Robert E. Lee had reinforced the Confederate defenders, a month-long lull fell over the trench lines. After the carnage at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse, North Anna, and Cold Harbor, Union commander in chief Ulysses S. Grant had continued trying to maneuver Lee into position for an open-field battle to destroy the Army of Northern Virginia, but Lee responded by fighting behind an elaborate trench system, hoping to hold out long enough to discourage the Northern people into forcing their leaders to make peace with the South. Lee had remarked to Maj. Gen. Jubal Early, “We must destroy this army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River. If he gets there, it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.”

Neither Grant nor the commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George Meade, was especially optimistic about the mine’s potential usefulness—Meade termed it “clap-trap and nonsense”—but they allowed it to proceed as a way to keep the bored soldiers busy. In late July, after problems in the Shenandoah Valley and a Union setback at the First Battle of Deep Bottom put pressure on Grant to break the stalemate at Petersburg, the mine’s potential took on a whole new significance to the Union high command. On July 26 Grant sent Maj. Gens. Winfield Hancock and Phil Sheridan on a diversionary attack against Richmond in an effort to get Lee to fatally strip his Petersburg defenses. Hancock’s II Corps and Sheridan’s two cavalry divisions failed to crack the Confederate fortifications, but they achieved their objective. After Lee ordered 20,000 men north of the James River, General P.G.T. Beauregard, commander of the Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia, was left with just three divisions at Petersburg, some 18,000 effectives in all.

Meanwhile, Pleasants’ men had come up with a viable alternative to costly frontal assaults and flanking maneuvers: they would go under the ground rather than over it. The 48th got almost no support from Meade or his chief engineer, Major James C. Duane, largely because the mine would have to be longer than 400 feet, a distance that would pose serious ventilation problems. Meade neglected to officially sanction the operation, allowing Duane to refuse the 48th the materials they needed to do the job: tools, timber, wheelbarrows, and sandbags. Left to their own devices, Pleasants’ men went to work anyway using improvised equipment, putting shovel to dirt on June 25.

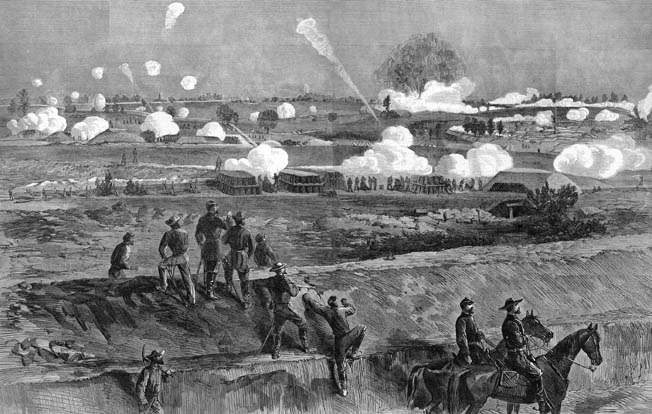

Pleasants and his 400 men completed the 511-foot shaft on July 17 in just three weeks—a mining miracle. Pleasants then devised an ingenious system to pump fresh air into the entire expanse when ventilation issues arose. Some 320 kegs of gunpowder—8,000 pounds—were placed in twin galleries below Elliot’s Salient, while enemy countermining efforts, belated and uncoordinated, came to naught. Orders were circulated that the mine would be ignited at 3:30 am on the 30th and that a massive infantry attack would commence immediately thereafter. During the night of the 29th, the Federals moved up 164 guns, including heavy mortars, siege guns, and Parrott guns. Also that night almost the entire IV Corps assembled behind the entrance of the mine, assuring the Federals overwhelming numerical superiority at the point of attack.

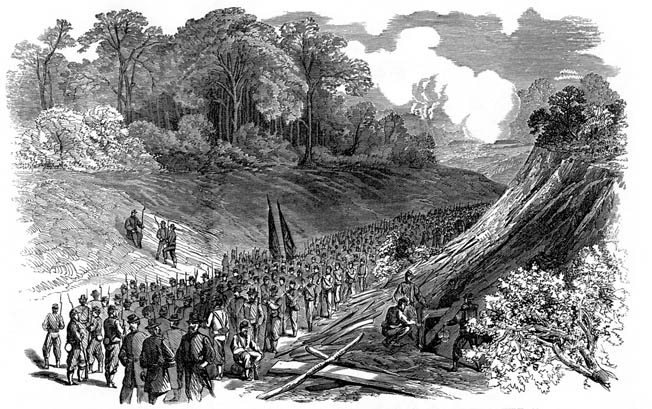

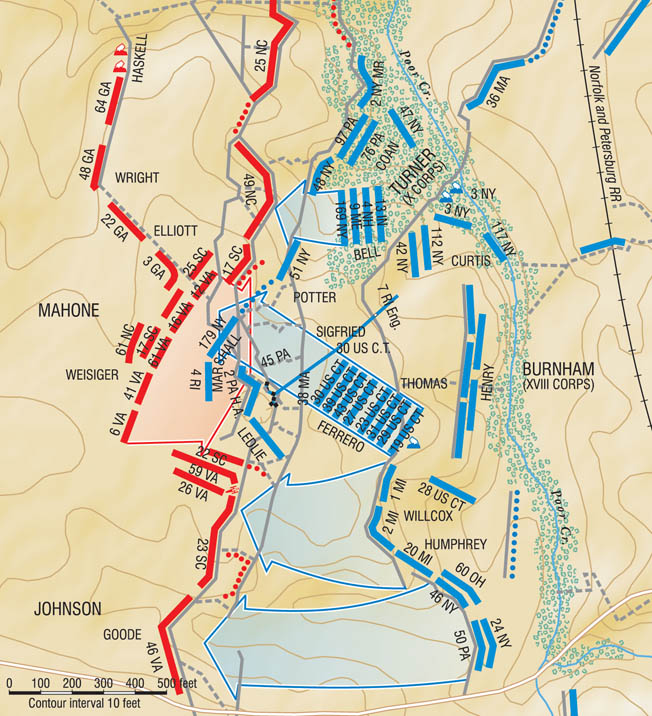

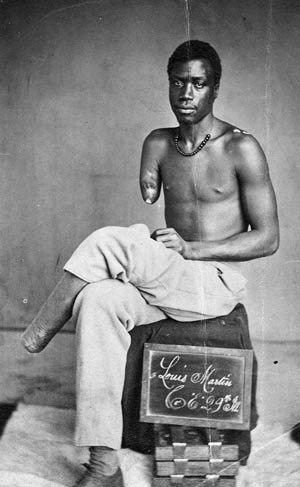

Three of Burnside’s four divisions, commanded by Brig. Gens. Orlando Willcox, Robert Potter, and James Ledlie, had been on line for 36 days, suffering at least 30 casualties a day from vicious sniping, and were exhausted from life in the trenches—drought, intense heat, bursting mortar shells, and sharpshooters’ bullets. Burnside’s fourth division consisted of two large brigades, nine regiments in all, of United States Colored Troops (USCT) under a white commander, Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero. They had yet to see combat, but they constituted Burnside’s freshest and largest division and had actually been drilled in preparation for the attack. Burnside had devised an exceptional plan: he would send the USCT division, 4,300 strong, through the gap created by the explosion in standard Civil War deployment—one brigade in front, the second in the rear in support. One regiment from each brigade would leave the attack column and extend the breach by rushing perpendicular to the crater, north and south, while the remaining regiments would advance through and push west toward the Jerusalem Plank Road and Cemetery Hill.

Burnside’s three remaining divisions, their flanks protected, would follow and drive west almost unopposed to help take Cemetery Hill, from which they had a clear shot at Petersburg. A possible rapid end to the war could be envisioned. The attack would mark the first deployment of African American troops into major combat in the Eastern Theater. Beyond the tactical problems of leading so large an assault, though, black soldiers and their white officers had to prepare for combat in which they could expect no mercy if they were captured or left wounded on the field. Colonel John Bross, commander of the 29th USCT, told the press, “When I lead these men into battle, we shall expect no quarter, and shall not ask for quarter.” Burnside was in high spirits; not only did he have units from two other corps standing by to help exploit the breakthrough if necessary—Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s XVIII Corps and Maj. Gen. Edward Ord’s X Corps—but he would have 144 field guns in support and all or part of another corps, Hancock’s, which might return from north of the James River in time for the battle.

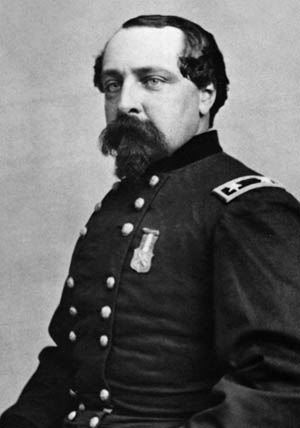

The day before the attack, Meade, after consulting with Grant, stunned Burnside by ordering him to spearhead the attack with a white, battle-tested division, a radical change that would have catastrophic repercussions. Grant and Meade feared political controversy if the black division was annihilated, with Grant fretting that they would be accused of “shoving these people ahead to get killed because we did not care anything about them.” Rather than choosing the best of his three other divisions to lead the attack, Burnside went into a funk after he was unable to get the order rescinded. When none of his three remaining division commanders volunteered to lead the assault, Burnside had them draw straws. Ledlie, a political general with no military training, and an alcoholic and coward to boot, won the honors—such as they were. Burnside’s willingness to allow possibly the worst general in the Union Army to spearhead the attack rather than one of his more experienced division commanders was a disastrous decision. With his ranks filled with inexperienced reinforcements and artillery units whose gunners were serving as infantrymen, Ledlie’s two-brigade division was the weakest in Burnside’s corps. Apparently, everyone in IX Corps knew of Ledlie’s shortcomings except Burnside. With less than 12 hours remaining before the attack, new plans had to be made. Rather than give Ledlie specific instructions, however, Burnside merely parroted Grant’s order to press forward and take Cemetery Hill at any cost. He then ordered Potter and Willcox to follow Ledlie, one veering to the left and one to the right, to be followed by the black division. He left all other tactical decisions to his subordinates. Ultimately, Burnside and Pleasants would spend the day 400 yards behind the Crater, protected by a 14-gun battery. Meade too remained safely back, another half-mile behind Burnside and Pleasants.

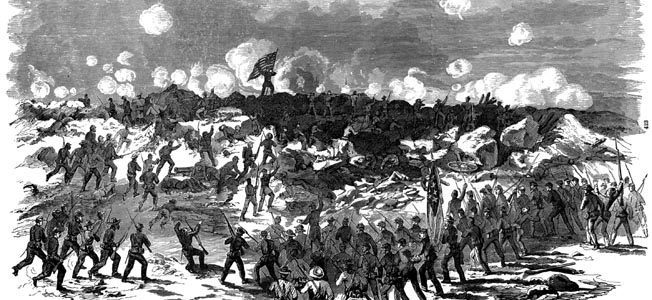

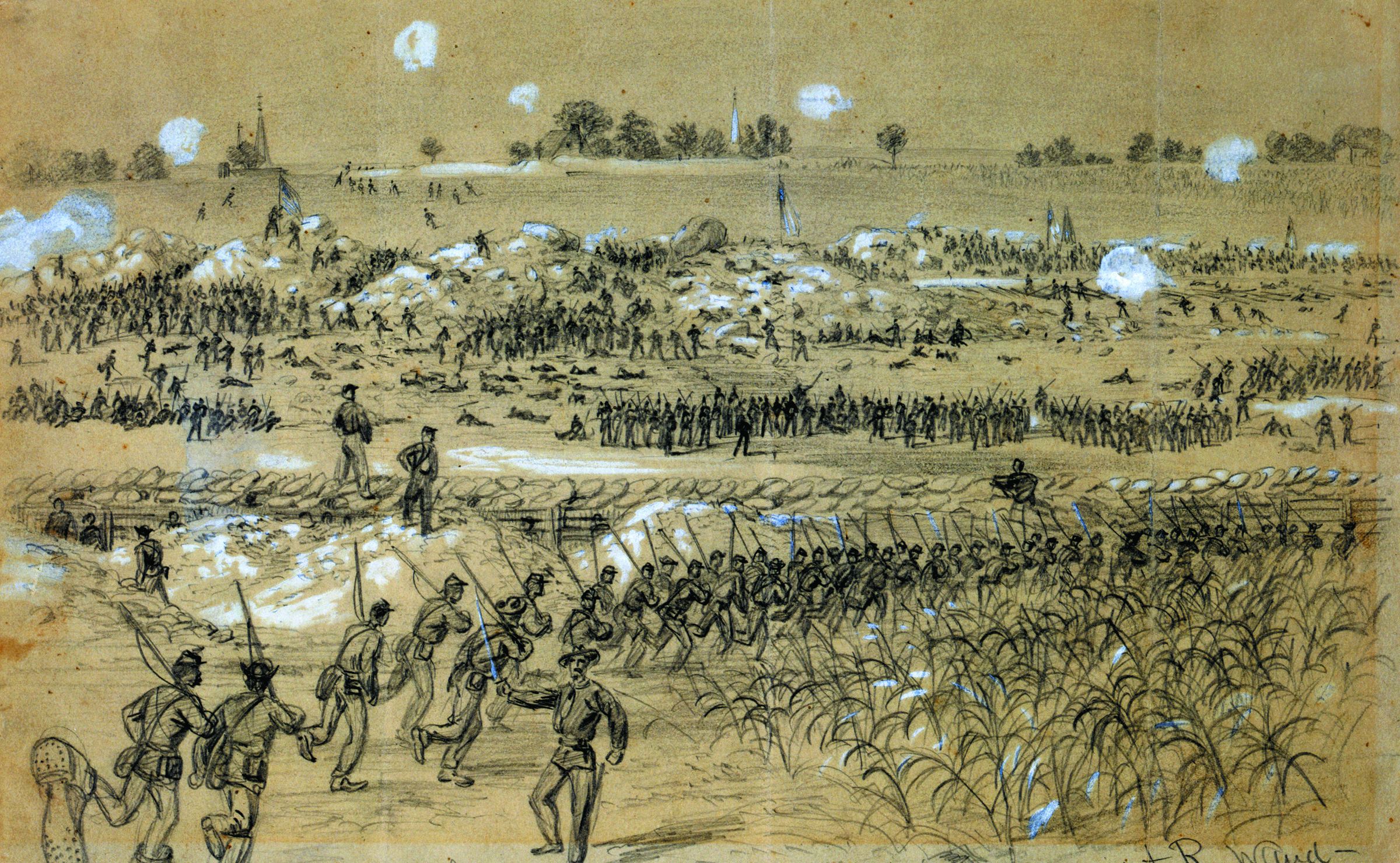

Slowly the men of IX Corps moved up on the night of the 29th into their assigned positions. Ledlie’s division was out front, just behind the ridge where Union pickets were dug in and just to the rear of the mine entrance. Potter’s and Willcox’s divisions were deployed along the slope of a railroad cut—the Norfolk & Petersburg Railroad bisected the Union line at that point—while Ferrero’s men waited in the bottom of the cut, chagrined at being shunted to the rear. Elsewhere along the Union line, the other corps waited as well, including Hancock’s, which now had returned, as hoped, from its movement beyond the James. A bad fuse delayed the detonation, but after it was relit the explosion came at 4:44 am. In a sudden, fiery blast, Elliot’s Salient ceased to exist. “Then came a monstrous tongue of flame shot fully two hundred feet into the air, followed by a vast column of white smoke,” recalled an onlooker from the 20th Michigan. “A great spout or fountain of red earth rose to a great height, mingled with men and guns, timbers and planks, and every other kind of debris, ascending, spreading, whirling, scattering and falling with great concussion to the earth once more.” Another Union onlooker, prefiguring a larger, more ominous blast 81 years later at Hiroshima, Japan, saw the smoke rising toward the sky “with a detonation of thunder spread out like an immense mushroom whose stem seemed to be of fire and its head of smoke.”

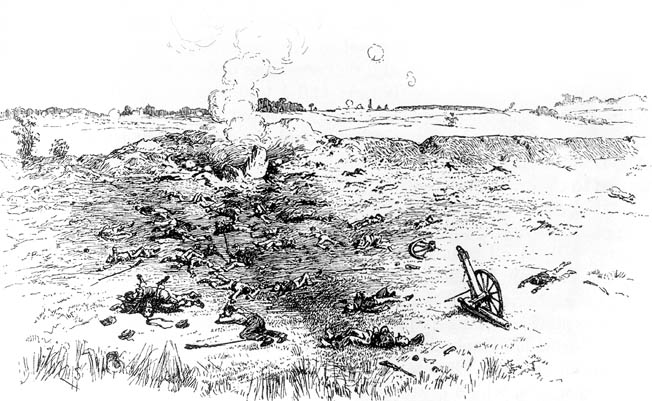

The fresh Crater, which would soon become a horrendous death trap for thousands of Union soldiers, first entombed half of Pegram’s guns and crews and entire companies of Elliot’s command, as well as damaging part of the cavalier trench. A total of 278 Confederates were sent to their graves by the huge blast. Great clods of dirt, some as large as houses, littered the floor of the Crater along with the torn bodies of its erstwhile defenders. Some defenders were seen running from the trenches, but most of the South Carolinians remained at their posts in the smoky haze. It would take a full half-hour for the stunned defenders to reorganize and put up any type of effective defense. “The way was completely open to the summit of the hill,” recalled a Union observer, “which was protected by no other line of works.”

After recovering from the shock of the blast, North Carolina and Virginia regiments positioned on either side of Elliot’s Salient shifted men to support the survivors of Elliot’s five South Carolina regiments. “When we arrived at our position,” a North Carolinian recalled, “we counted twelve United States flags in the works, and the whole field in front of the crater was filled with Yankees.” Confederate defenders on both sides of the Crater began pouring a deadly fire from both flanks into Ledlie’s men while well-placed artillery raked the ground on all sides of the pit. An indecipherable labyrinth of trenches, bombproofs, and covered ways also helped freeze the first wave of Federals in place. Stunned by the explosion and the deafening roar that followed when all the Union batteries opened as one, the front line of bluecoats scrambled for the rear through a massive wave of detritus from the blast and an accompanying cloud of dust. Ledlie ordered his two brigade commanders, Brig. Gen. Frank Bartlett and Colonel Elisha Marshall, to open the attack, after which Ledlie himself retired to a nearby bombproof to sit out the battle, swigging rum from a bottle he had cadged from his staff physician.

The Federals were wasting precious time; it took 15 minutes for Marshall and Bartlett to coax their hesitant troops back to their original positions and send them over the top. Almost immediately the attack went awry. In dismay over the last-minute change in plans, the flustered Burnside had neglected to have the defensive obstacles cleared from in front of the Union trenches to allow easier passage for the attacking columns. Nor had anything been done to help the attackers scale their own six-foot-high trench walls—ladders that were to help Union soldiers traverse their trenches never appeared. Improvising quickly by jabbing their bayonets into the logs above them, Union attackers climbed their makeshift stepladders out of the trenches. Creeping forward in small groups rather than advancing on a broad front, Ledlie’s men struggled to scale the trenches and lurched across the debris-strewn no-man’s-land toward the Confederate works. Navigating their own trenches had literally destroyed the Federal dispositions. Three regiments of Ledlie’s men, after being ushered through a hastily improvised 10-foot passageway, finally arrived at the explosion site.

There they were stunned to see the crown of the salient’s ridge had been replaced by a high wall of fresh earth, beyond which yawned a fresh crater 170 feet long, 60 feet wide, and 30 feet deep. To many Union soldiers, inured to searching for protection when under fire, the Crater looked like the biggest and safest foxhole they had ever seen—except that it wasn’t safe at all. Its steep 30-foot walls and slippery, sandy white clay made it nearly impossible to escape once the men had entered the pit. Instead of moving around the hole and heading for the high ground—Cemetery Hill lay just 500 yards away—Federal soldiers stumbled instead into the smoking abyss, using it as a vast rifle pit. A choking pall of dust and smoke blanketed the area.

Paralyzed by conflicting orders and lack of leadership, Ledlie’s attackers failed to either widen the breach, as Ferrero’s troops had been drilled to do, or push up the slope toward Cemetery Hill. “Our orders were to charge immediately after the explosion,” recalled Union Major Charles F. Houghton of the 14th New York Heavy Artillery, “but the effect produced by the falling earth and the fragments sent heavenward that appeared to be coming right down upon us, caused the first line to waver and fall back.”

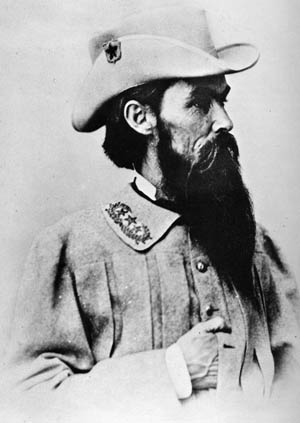

At his headquarters north of the Appomattox River, General Lee was notified of the attempted breakthrough at 6:15 am. He rushed orders for Brig. Gen. William Mahone, whose division was camped about three miles west of the Crater constituted Lee’s closest reinforcements, to send two brigades to the scene of the crisis. Mahone, nicknamed “Little Billy” for his diminutive size and shrill, piping voice, chose a Georgia unit and his own Virginia Brigade, also known as the Old Dominion Brigade and including many men from Petersburg eager to defend their homes, to make the march. Using streambeds, back roads, and covered ways, Mahone and his men arrived a little after 8 am. Lee rode to the front, arriving at Maj. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s command post not far from Cemetery Hill, from which vantage point Lee could clearly see the Crater and the Union units massed in and around it. He, Johnson and Beauregard rode to the Gee house at the juncture of the Baxter and Jerusalem Plank roads, 500 yards west of the Crater, where they climbed to the second floor to monitor the action.

As Confederate musket fire picked up, Bartlett pushed some of his troops into trenches south of the Crater while Marshall directed his soldiers to the north and west. Only a relative few men in the Union advance got as far as the maze of works beyond the Crater, where they began exchanging fire with a small group of Southern defenders. Unit leaders of the main body were ignored as they shouted and pointed their swords toward Cemetery Hill, and there wasn’t anyone of superior authority to salvage the situation. Burnside, at least, should have been in close communication with the front. He was not.

Troops of one of the heavy artillery units fighting as infantry found a working gun and began utilizing it against the defenders to their west. Union reinforcements continued pouring into the breach as Burnside ordered his next two divisions forward, those of Potter and Willcox, but most of the attackers, rather than going forward toward Cemetery Hill, either joined their comrades in the Crater or branched out to the immediate right and left along the lines. As the Federals continued wasting precious time, 8- and 10-inch mortars in the Confederate rear, along with well-placed artillery batteries, began pouring a deadly storm of shell and canister into the crowded masses milling in and around the base of the Crater. Finally, fairly large groups of Union soldiers formed near the Crater’s western edge and began filtering into the captured Rebel trench system.

Two light Confederate artillery batteries under Major John Haskell hurried up the Jerusalem Plank Road and unlimbered near Cemetery Hill. Exposed to Union sharpshooters and artillery fire, Haskell nonetheless opened fire on his own and began the most effective effort of the day by either side. Haskell entered the covered way, which led 500 yards from the Jerusalem Plank Road directly to the Confederate works north of the Crater, and asked Elliot for infantry to support his exposed guns. Responding to Haskell’s request, Elliot was severely wounded when he tried, with a brave handful of fellow South Carolinians, to comply. Colonel Fitz McMaster assumed command and led 200 survivors of the 26th South Carolina into a creek depression west of the Crater, within the defensive works, where comrades from Elliot’s other regiments rallied upon them. They were, for the moment, the only Confederate forces standing between the Crater and Cemetery Hill.

Several North Carolina brigades commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom moved south to link up with the left flank of the 26th South Carolina and Virginians from Brig. Gen. Henry Wise’s brigade to repair the line and support McMaster. A number of disorganized Union thrusts were repulsed. By 8:30 am, after Potter’s and Willcox’s divisions entered the fray, a large part of the Union IX Corps, about 10,000 men, had reached the destroyed enemy salient, most of them milling around the Crater. When Willcox led his division into action, he ordered a brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. John Hartranft to expand the breakthrough south of the Crater. Its lead regiments, however, were once again drawn inexorably toward the massive hole, where they became entangled with Ledlie’s troops. Two other regiments simply halted on the rising slope. Stunned by this development, Willcox strongly cautioned Burnside against advancing any more troops.

Meade, exploding in anger when informed of the bottleneck at the Crater, summarily ordered Burnside to have all Union troops push forward to the crest of Cemetery Hill, regardless of their current dispositions. Willcox tried hard to comply, ordering the 27th Michigan straight into the teeth of Wise’s Virginians, who halted the advance in minutes. Meanwhile, Willcox’s second brigade, under Colonel William Humphrey, moved up, only to find its front partially blocked by Hartranft’s stalled column. Under fire and eager to advance, Humphrey sent his entire command surging across the abatis-strewn field, where they crashed into the Confederate works, capturing prisoners and relieving, for a while, the pressure on the south flank of the Crater. Humphrey’s success was fleeting, however; the Virginians rallied, and South Carolinians firing at the Crater turned their attention to the new threat. Humphrey’s left flank quickly crumbled and three Michigan regiments found themselves isolated within the Confederate lines, taking fire from three directions.

Burnside’s ambitious plan to seize Petersburg and bring a quick end to the war was disintegrating in a jumble of Union command failures and unexpectedly stiff Confederate resistance. Meade continued to insist that all Union units rise up en masse and take Cemetery Hill. Burnside opted to take the word of his commanders on the scene, who informed him that there was literally no more room for added units to deploy and that any reinforcements would be a waste of manpower. Nevertheless, sometime after 7 am, Meade ordered Burnside to commit his fourth and last division, Ferrero’s USCT troops. As his units advanced into the teeth of enemy fire, Ferrero clambered into Ledlie’s bomb shelter, where he huddled, sharing a bottle of rum with Ledlie, for the remainder of the battle.

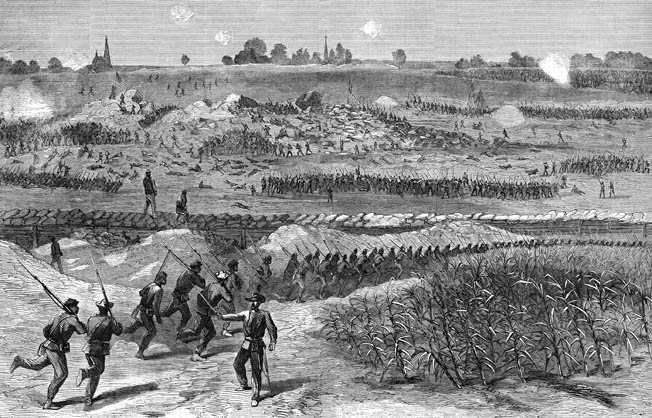

The USCT advance was blocked by a steady flow of returning wounded, panicked comrades, and Confederate prisoners coming from the front. After Lt. Col. Joshua Sigfried ordered his brigade forward, the black troops stolidly negotiated the obstacles leading to the front only to come under galling fire all along their column. Parts of the two leading regiments forced their way through the congested mass inside the Crater. while others skirted the abyss north of it, all disappearing into the honeycomb of enemy trenches and bombproofs. In the turmoil, the 30th USCT fired on the 9th New Hampshire and rendered it hors de combat. Despite the blunder, the black troops moved into the Rebel entrenchments and confronted the 17th South Carolina, inflicting and suffering heavy casualties as they pressed ahead.

More of Sigfried’s brigade followed and helped launch the fiercest Union attack of the day as the African American fighters captured the damaged cavalier trench held by Elliot’s survivors, all the while screaming, “No quarter, remember Fort Pillow!” in reference to the recent notorious slaying of several dozen black troops during or after the battle for the West Tennessee fortification. They rounded up hundreds of prisoners, killing any who showed the slightest resistance, and after hours of stalemate it seemed that the breach might begin to expand.

Ferrero’s second brigade commander, Colonel Henry Thomas, however, trying to follow up on the success of Sigfried’s men, lost control of his regiments when they descended into the maze north of the Crater or moved into the pit itself. Thomas managed to get some of his men formed on Sigfried’s left flank west of the cavalier trench, but a barrage of shells and bullets blasted them back into the trench. McMaster’s Confederates, still sheltering inside the creek depression 200 yards to the west, massed their fire into the van of Sigfried’s advance, wrecking it. Ferrero’s depleted ranks fell back into the cavalier trench.

Burnside, who would be instructed by Meade to order a withdrawal in less than an hour, still believed his men had another charge in them. He ordered Sigfried and Thomas to again attack Cemetery Hill, reinforced by Marsh and Bartlett, Ledlie’s two brigade commanders. Waving a regimental flag, Bross of the 29th USCT climbed out of the cavalier trench and exhorted his men to follow him. The courageous remnants of the division moved up and formed a ragged line on the colors. With Cemetery Hill 500 yards away in plain sight, the USCT troops once again moved forward into the fiery summer morning.

Shortly after arriving at the front, Mahone saw the confusion in the Federal ranks but, concerned about the enemy’s numbers, he called for his third brigade—Willcox’s Alabama troops under the command of Colonel John Sanders—to come up as well. Colonel David Weisiger’s five Virginia regiments had led Mahone’s initial march, moving through the covered way into the creek depression where McMasters’ South Carolinians had made their heroic stand. Mahone sent the Georgians to support Weisiger’s right flank, and as the Rebels moved into place, word spread that black units had taken part in the last attacks and that no quarter had been asked or given. By 9 am Mahone’s units were in place, locked and loaded, with bayonets fixed.

About 200 black troops had answered Bross’s call and begun advancing west from the cavalier trench, their cheers catching the attention of Weisiger’s men. In a line 200 yards wide and three lines deep, Weisiger’s Virginians, backed by two North Carolina regiments, McMaster’s survivors, and parts of two Georgia regiments, leaped out of the creek depression and charged the isolated and outnumbered USCT column, which floundered and fell back. Mahone’s gray wave approached the cavalier trench, where it was met with a sweeping Union volley. The fire tore gaps in the Confederate line but couldn’t slow it down, the attackers sweeping over the last few yards and crashing into the trench.

Fierce fighting exploded along the entire front, bayonets flashing and gun butts flailing. With the cavalier trench cleared, the Confederate defenders worked their way toward the crowded blue maze north of the Crater, killing with abandon and taking few prisoners, white or black. Again panic struck the Union ranks, and mobs of men turned and headed back for the Crater only to find the intervening ground a cauldron of lethal crossfire. With Mahone’s attackers in hot pursuit, most of the fleeing bluecoats tumbled into the perceived safety of the Crater. There, in a ghastly turn of events, some panicky Union troops bayoneted incoming black troops, fearing enemy reprisals if they were captured fighting alongside the black troops.

Approaching Confederates deployed movable Coehorn mortars 50 feet from the Crater and began sending a steady stream of shells into the churning morass. “We got closer and closer to the enemy,” recalled a Confederate battery commander, “until we were throwing shells with such light charges of powder that they would rise so slowly as to look as if they could not get to the enemy, who were so close that we could hear them cry out when the shells would fall among them, and repeatedly they would dash out and beg to surrender.” Mahone, whose Virginians by now had captured most of the line north of the Crater, ordered a line of sharpshooters to target the western edge of the Crater while sending the rest of his Georgia brigade against its southern flank. The Georgians made two bloody attacks and extended Weisiger’s line to the south but failed to take the trenches south of the Crater. The Union mass in the smoldering rubble stubbornly held on, resisting all efforts to push them out of their man-made hole.

Mahone’s attack had taken about an hour. Before it began, Burnside had begged Meade to allow fresh V Corps units to join the fray, but at 9:30 am Meade sent orders instead for Burnside to begin conducting a withdrawal. The angry Burnside sought out Meade and in “language extremely insubordinate” demanded the operation continue with the aid of V Corps. After Grant arrived and backed Meade, a disconsolate Burnside returned to his headquarters and prepared to pull his commands back to safety. He would, however, be in no particular hurry to do so. Scores of additional Union troops would die because of his tardiness.

As the merciless summer sun baked the horrid pit, Union soldiers used the bloated bodies of dead comrades as makeshift parapets. Some Federals braved the hell of no-man’s-land in a heroic effort to bring water and ammunition back to their comrades. Despite the dreadful conditions and abject confusion, the Federals continued somehow to keep the defenders at bay, throwing back a series of limited Confederate thrusts. More and more survivors crawled out of the Crater and headed back toward their own lines, enduring a galling crossfire that killed and wounded hundreds more. In the pit’s southern recesses, Chippewa Indian riflemen from the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters covered their heads and sang their death songs amid the deafening roar of battle. At 12:30 pm, word arrived that Burnside had given up and ordered a withdrawal; Union officers at the front were told to use their discretion as to the timing and method of withdrawal.

With the fighting now spread over a square mile centered on the Crater, the battle was about to turn in the defenders’ favor for good. A few hundred yards to the west, Mahone prepared to apply the coup de grace. He sent Sanders’ five Alabama regiments down the covered way into the creekside depression, telling Sanders to march his brigade around the friendly troops to his front (Wright’s Georgians) and come in against the Crater from the southwest. Their orders were simple: clear the Yankees, black and white, from the line. The method was simple as well: one shot, then the bayonet. They would advance just before 1 pm under an artillery barrage while Lee and other commanders watched from the Gee House.

Supported by North and South Carolina units, the Alabama troops stepped off smartly. Once they passed the cavalier trench, however, they came under heavy fire from the Crater. The last few yards proved the toughest. On level ground, the Confederates were momentarily exposed to Union artillery that blew great gaps in the gray lines. The attackers doggedly closed ranks and came on, reaching the edge of the Crater before they had suffered more harm.

In these last minutes, Union resistance centered at the Crater’s western edge crumbled in vicious fighting. Federal muskets with their bayonets still attached lay scattered about everywhere, and opportunistic Confederates picked them up and launched them like javelins into the teeming blue crowd. Confederate soldiers surged over the Crater’s rim and into the pit, slashing their way forward. Bayonets, knives, and muskets used as clubs were the weapons of choice as the dense mass of humanity left little room for maneuver. The Rebels again refused to accept the surrender of black troops, dispatching them with brutality. Once more, fearing Rebel reprisals, many white Federals killed their black comrades in a craven attempt to ensure their own survival.

With Confederates pouring over the top, Griffin and Hartranft yelled for any Northerners within range of their voices to retreat. The Union perimeter disappeared as a flood of survivors crawled out of the pit and headed back through no-man’s-land. With Rebel mortars and artillery bracketing the area, more Federals were killed and wounded in the retreat than in Ledlie’s morning attack. Those at the back of the pack turned and faced their pursuing tormenters, the fighting as savage as any witnessed in the entire war. “Our fellows seized the muskets abandoned by the retreating enemy,” wrote one Confederate soldier, “and threw them like pitchforks into the huddled troops over the ramparts. Screams, groans and explosions throwing up human limbs made it a scene of awful carnage.”

By 1:30 pm the battle was over with the exultant Confederates taking full possession of the Crater and the field works surrounding it. Pioneers and engineers worked all night to incorporate the Crater into the Confederate defenses. Meanwhile, within the Union lines, Burnside sat stunned as casualty figures came in. At 3 pm, Potter reported that his division was annihilated. Full regiments had been captured whole, and the majority of his field officers had been killed or wounded. Other division commanders reported similar heavy losses, and stories of the heartless treatment of USCT soldiers—by Rebels and Yankees alike—shocked Burnside, who struggled to make sense of the tragedy. He had committed 14,000 men from his corps and within six hours had lost nearly 35 percent of them. Despite numerous requests, Burnside waited until the next evening to report to Meade, finally admitting to a loss of almost 4,000 men, which he blamed on the lack of support from adjoining corps that were not committed.

The battle was over, but the repercussions were still to come. During a battle that reeked of command malfeasance on a scale that equaled that of Cold Harbor—two drunken Union division commanders sitting out the battle behind the lines—the Union Army suffered 3,798 casualties, including 504 killed and 1,881 wounded. Fully one third of the casualties were suffered by black troops, including 219 killed in action and almost 1,000 wounded, the worst day for USCT troops in the entire war. A large number of Union casualties occurred after Meade and Grant had ordered a withdrawal, but both commanders were too far from the lines to realize Burnside had delayed sounding the recall. Meade had now suffered almost 6,000 casualties for the month with almost nothing to show for it (Lee could take a little comfort that Confederate casualties were less than half of Meade’s). Most of the Confederate dead at the Crater were killed in the explosion that opened the battle; the defenders lost 361 men killed, 727 wounded, and 403 missing or captured for the day. The Confederate victory didn’t change the strategic situation, which meant that the siege of Petersburg would drag on for another eight bloody months.

There was plenty of blame to go around on the Union side. Meade and his chief engineer had failed utterly to support Pleasants’ mining efforts, and Meade and Grant had changed Burnside’s attack plans at the last minute for political reasons. Burnside had failed to issue new and specific attack orders to Ledlie and delayed sending orders for his corps to retreat. Ledlie (but not Ferrero, who amazingly was overlooked in the aftermath) was soon sent packing, condemned by a court of inquiry along with Burnside, Willcox, and Colonel Zenas Bliss, for his part in the mismanagement of what Grant called “the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war.” Burnside left on the heels of a violent argument with Meade, who wanted his corps commander court-martialed for incompetence. Grant, preferring a quieter procedure (and with the memory of his own misguided attack at Cold Harbor still fresh in his mind), sent Burnside home on leave, summing up the battle as “a stupendous failure, all due to inefficiency on the part of the corps commander and the incompetency of the division commander who was sent to lead the assault.”

Resigning from the service, Burnside returned to Rhode Island, where he slowly recovered the geniality he had lost in the course of a calamitous Civil War career that had required him to occupy positions he himself had warned he was unqualified to fill. He found a large measure of solace in early 1865, when the Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War exonerated him and condemned Meade for changing the plan of attack at the last minute.

The Petersburg campaign—it wasn’t a siege in the true sense—encompassed 292 days of combat, maneuver, and trench warfare between June 15, 1864, and April 3, 1865. After the fiasco at the Crater, Grant spent the next eight months focusing on severing Petersburg’s many road and rail connections to the south and west. He launched a total of nine offensives—the Battle of the Crater taking place during the third—in the campaign, striking both north and south of the James River. After six weeks of vicious fighting, the combat subsided into a prolonged stalemate in the trenches before Petersburg and Richmond that anticipated the gruesome conditions on the Western Front during World War I.

Pleasants had remained with Burnside on the parapet of a 14-gun Union battery during the battle and watched in horror as his men’s incredible excavation effort—a legitimate mining marvel—went for naught. When things finally went horribly wrong, he angrily told Burnside that he had “nothing but a damned set of cowards in your brigade commanders.” Many of Pleasants’ surviving troops would have agreed with the colonel’s assessment. For thousands of others, of course, it was then too late to say.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments