By Blaine Taylor

During the October 1813 Battle of Nations at Leipzig between the French, under Emperor Napoleon I, and the German-Swedish-Russian-English coalition, French troops were astonished to see whooshing smoking rockets flying at them from enemy lines. Some Americans had already been on the receiving end of the swift erratic projectiles, and would be again as the British shifted their wrath to the recalcitrant cousins in the New World.

The British, under Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn, had already led a fiery raid on the Maryland town of Havre de Grace in May 1813, using rockets to help drive the land defenses inward as his sailors and Royal Marines struck from the water by barge. A year later the British used rockets again in the twin June 1814 Battles of St. Leonard’s Creek in southern Maryland—in which a sailor was killed in the Chesapeake flotilla of Commodore Joshua Barney. He, and a man named Webster at Havre de Grace, are the only known casualties ever inflicted by the famous Congreve rockets.

[text_ad]

The exotic weapons were used to great effect, however, in routing an American militia army at Bladensburg, Md., on August 24, 1814, as well as to burn the U.S. Capitol, Treasury Building, Navy Yard and White House in Washington during the 24th and 25th.

On September 12, 1814, however, some of the same troops who had fought at Bladensburg stood their ground better against the rockets at North Point, Md., in defense of Baltimore, although the rockets did succeed in setting fire to some haystacks and farm buildings. By the time of the Battle of New Orleans, on January 8, 1815, however, the word was out about the fearsome weapons, namely that they constituted more bark than bite.

Sir William Congreve’s Rocket Artillery

Highly mobile on land—far more so than artillery—their mean range was about two thousand yards. They were not particularly accurate but were best suited to setting buildings afire and startling defenders.

Although rockets had been developed and used in warfare by the Chinese as early as the 13th century, these British rockets were the brainchild of Maj. Gen. Sir William Congreve (1772-1828), a most inventive officer.

Sir William was the son of a general in the Royal Artillery and was schooled at the Royal Academy at Woolwich. Later, working at the Royal Laboratory at Woolwich, where his father was Comptroller, the younger Congreve developed his kind of rocket in 1808. The British first tried them in action against the French fleet in Basque Roads in 1809. Its success was not so great as had been expected, but its value was perceived, and the inventor was allowed to build two rocket companies in connection with the Corps of Royal Artillery.

This done, one of Congreve’s rocket companies served at the Battle of Leipzig. The rockets did not do much effective damage, but their shrieking, flame, smoke and explosions aided the Allied cause by frightening and confusing the French, who ultimately retreated in disarray.

Writing in his 1814 book Details of the Rocket System, Congreve explained, “The rocket is a species of fixed ammunition which does not require ordnance to project it, and which, where apparatus is required, admits of that apparatus being of the most simple and portable kind. In battle, rockets [may] be merely laid in the ground in the direction required, and, if an enemy be advancing toward him, he may choose his volley from 50 to 500—a fire which, if judiciously laid in, must nearly annihilate his enemy. This practice also requires the exposure of only one or two men.”

In another work on rocketry, Congreve even anticipates the German rockets of 1944. “From experiments I have lately made, I have reason to believe that rockets much larger than those mentioned may be formed. Rockets from half a ton to a ton weight, which being driven in very strong and massive cast iron cases, may possess such strength and force that, being fired, even against the revetment of any fortress, pierce the same; and having pierced it, shall with one explosion of several barrels of powder, blow such portion of the masonry into the ditch, as shall with very few rounds, complete a practicable breach.” Hitler’s V-1 and V-2 rockets blasted a good deal of London and Antwerp masonry.

The Royal Navy’s Rockets

Congreve theorized that boats firing rockets could be used to board other naval vessels at sea: “The moment of coming alongside, the fuses are lighted: and the whole number of rockets immediately launched by hand through the ports into the ship; where, being left to their own impulse, they will scour round and round the deck until they explode, so as very shortly to clear the way for the boarders, both by actual destruction, and by the equally powerful operation of terror against the crew; the boat lying quietly alongside for a few seconds, until, by the explosion of the rockets, the boarders know that the desired effect has been produced, and that no mischief can happen to themselves where they enter the vessel.”

Congreve rockets were used in this way from boats when Cockburn took the land batteries at Havre de Grace in 1813, but the British were unable the following year either to sink or take Commodore Joshua Barney’s Chesapeake flotilla at St. Leonard’s Creek on two separate occasions. At the battle of Craney Island, Va., in June 1813, the British were unable to loose rockets to board the U.S. Frigate Constellation because the foolish Royal Navy frontal attack by barges and gunboats was easily broken up and beaten back by the guns of the Constellation as well as from shore batteries. Even when Barney’s 17-boat flotilla was finally trapped at Pig Point, Md., by both British barges and ground troops on land, the British were unable to board them after a rocket barrage, because the wily American seadog Barney had scuttled the boats with explosives just as the British riverine force arrived, his men long since departed overland for Bladensburg, where their cannon and muskets would clash again with Congreve rockets.

Congreve’s Rocket Ammunition

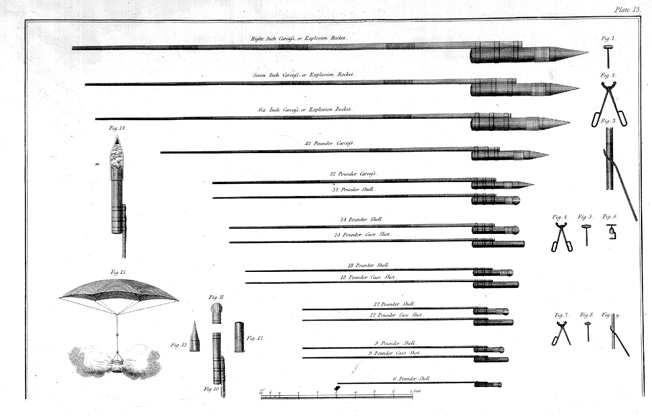

Congreve developed three kinds of rockets, which he called heavy, medium and light. In a chapter entitled “Rocket Ammunition” from one of his several treatises he wrote, “The heavy natures are those denominated by the number of inches in their diameter; the medium from the 42-pounder to the 24-pounder inclusive; and the light natures from the 18-pounder to the six-pounder inclusive.”

He continued: “The range of the eight-inch, seven-inch and six-inch rockets are from 2,000 to 2,500 yards, and the quantities of combustible matter, or bursting powder, from 25 pounds and upwards to 50 pounds. The 42-and 32-pounders are those which have hitherto been principally used in bombardment. These convey from 10 to seven pounds of combustible matter each and have a range of upwards of 3,000 yards.

“The 42-and 32-pounder rockets may also be used as explosion rockets and the 32-pounder armed with shot or shells; thus a 32-pounder will range at least 1,000 yards, laid on the ground and armed with a 5 1/2-inch howitzer shell, or an 18-or even a 24-pounder solid shot.

“From the 24-pounder to the nine-pounder rocket inclusive, a description of case shot is formed of each nature, armed with a quantity of musket or carbine balls, put into the top of the cylinder of the rocket, and from these discharged by a quantity of powder contained in a chamber, by which the velocity of these balls, when in flight, is increased beyond that of the rocket’s motion.

“All rockets intended for explosion, whether the powder be contained in a wrought iron head or cone, as used in bombardment, or in the shell mentioned above, for field service, or in the case shot, are fitted with an external fuse of paper, which is ignited from the vent at the moment when the rocket is fired. These fuses may be instantaneously cut to any desired length, from 25 seconds downwards, by a pair of common scissors or nippers, and communicate to the bursting charge.

“All the rocket sticks for land service are made in parts of convenient length for carriage, and jointed by iron ferules. For sea service, they are made in the whole length,” concluded Sir William.

The Burning of Washington and Baltimore

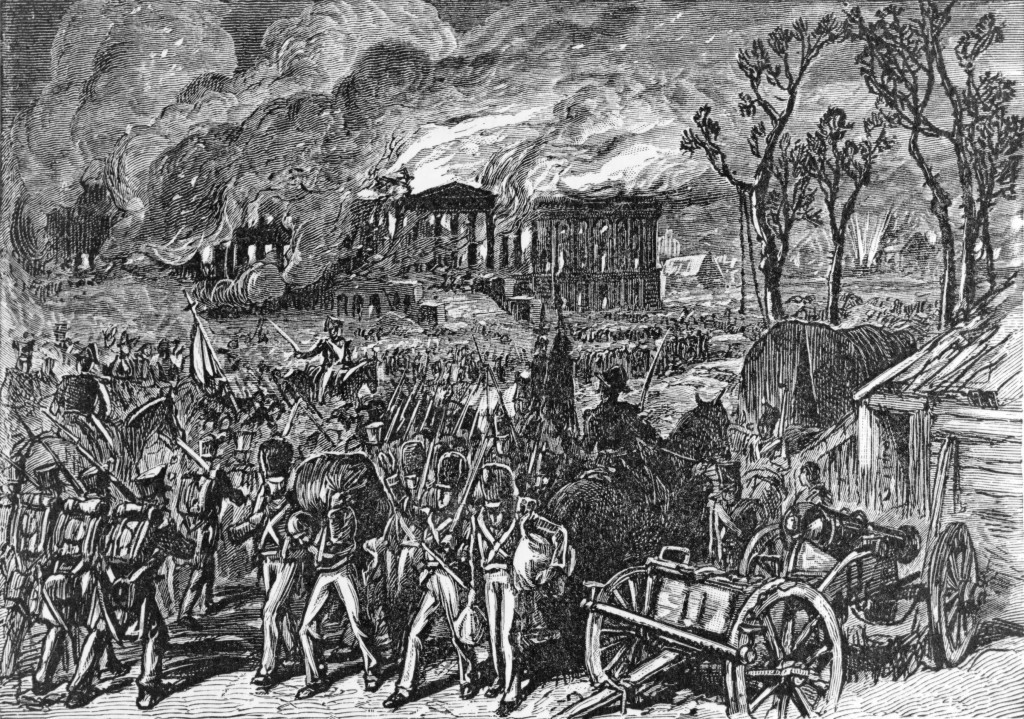

Thus were the British armed when they began their raid of retribution and destruction up the Chesapeake Bay in 1814. Against the American line defending the U.S. capital at the Battle of Bladensburg, the British used the Congreve rockets mainly for terror. According to Francis Beirne in his 1949 work The War of 1812, “To men in the trenches or under cover, [the barrage of rockets] gave little concern, but to the troops of [militia commanders] Sterett, Schultz and Ragan who stood open to view, thanks to Col. (later President James) Monroe’s dispositions, they proved a very definite menace. The first volleys flew high, but those that followed were lower and grazed the heads of militiamen.

“What with the rockets and the confusion caused by the retirement of Pinkney’s riflemen, [Lt. Col. John] Ragan’s and [Lt. Col. Jonathan] Schutz’s men next were seized by the surrounding panic and with a few marked exceptions turned and raced for the rear.”

With the collapse of the defense of Washington, the British land army under Maj. Gen. Robert Ross marched into the capital of the young republic and set fire to its major buildings, likely in retaliation for the American torching of York and Newark in Canada.

The British soldiers used rockets to begin the arson. At first in the Capitol’s House of Representatives they fired rockets into the ceiling, but to scant effect—it was covered in sheet iron. So they piled the mahogany tables, chairs and desks in the center of the room, sprinkled them with rocket powder and fired some rockets into the pile. The fire was spectacular and the ignition method was thus repeated in the Senate, Treasury Building and White House.

Then began the raid to burn Baltimore, comprising for the main the land action called the Battle of North Point, and the bombardment to reduce Fort McHenry defending Baltimore’s seaside. At North Point, the British duplicated the tactic that had worked at Bladensburg—firing at the Americans with rockets to terrorize and confuse them. According to Beirne, “The shriek of the rockets was more than the men of the [militia] 51st could stand. They hesitated, then broke. Ignoring the pleas of their officers, they fled the field, every man for himself.”

Baltimore author Neil Swanson described the rockets used at North Point this way in his 1945 The Perilous Fight: “A streak of something leaps across the river. It spits fire backwards. It looks a great deal like a comet. It rises, arches, clears the willows. It’s curving down toward the field, it’s beginning to wobble. You can see the stick swishing behind it. It hits the ground a good way in front of the guns. It lies there, not long, only a second; a man can see it quiver. As if it had taken a good, deep breath, it whooshes again. It acts like a crazy thing.”

The Battle of Fort McHenry and the End of the Congreve Rocket

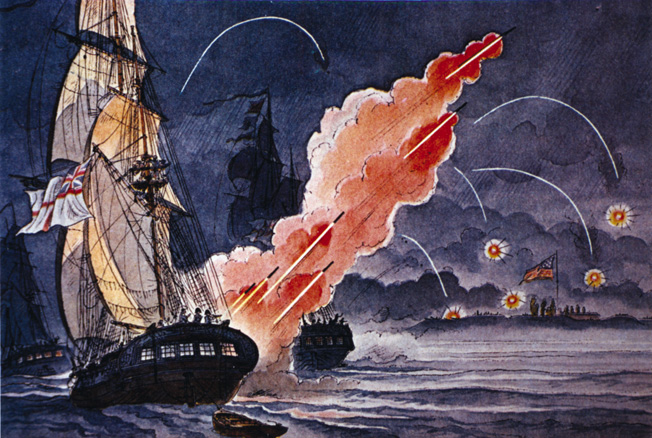

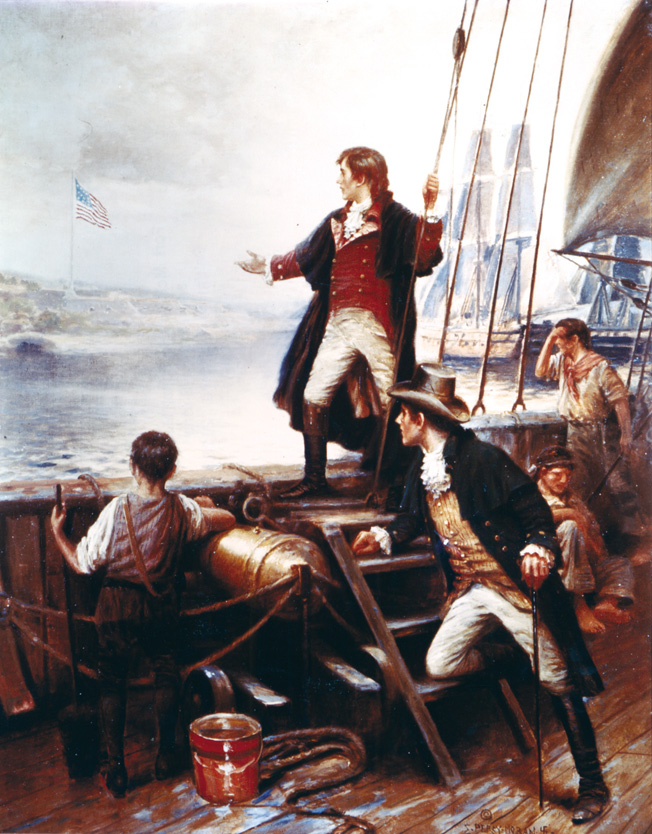

In the assault on Fort McHenry hard on the attack at North Point, the British used the HMS Erebus as a rocket-launching warship. Stocked with Congreve rockets and their launching tubes, it provided many of the “rockets’ red glare” noted by Francis Scott Key, who witnessed the bombardment and was moved by the American resistance in the face of the new weapon.

According to Swanson, “The function of the Erebus was not solely to spread terror.… Her prime mission was destruction. She was firing carcasses—incendiary shells. The hollow warheads of her rockets were packed solid with combustibles, saltpeter, pitch and sulphur and corned powder.”

But the rockets of the Royal Navy were as inaccurate as those of the army. Some landed and stuck in the earth, some fell short into the Patapsco River only to bob up again, harmless, and float like so many dead fish.

The Erebus still had her 20 cannon, but below the gun decks, shipwrights had cut square holes. Leading to each was a boxed frame slanting down to the hold. Inside each frame was a metal discharge tube carrying 32-pound rockets, which were discharged with lanyards. According to Beirne, the frames with their tubes could be raised or lowered so that the rockets could be launched horizontally—in the case of attacking another ship—or up to 85 degrees from horizontal for longer range.

Such rockets could carry 24-pound solid shot, an explosive shell, or inflammatory material. According to Congreve, each shell was at least the equal of a 10-inch spherical carcass and 10 rocket ships like the Erebus could discharge two hundred rockets in a few minutes, not the two hours required by mortar ships discharging a like amount. Again, according to Congreve, one rocket ship hurling 32-pound rockets would be the equivalent of 10 mortar vessels.

But for all of this the bombardment of Fort McHenry was a failure. Although rockets rained down on the place and the powder magazine was hit, the damage was insufficient. The powder magazine did not blow up, and the walls were not breached. Nor was the garrison caused to abandon the fort in panic. Nor were the guns put out of action, and the British vessels faced horrible punishment if they ventured to sail in closer.

Thus the punishment of Baltimore was abandoned and soon, too, the Congreve rockets. Partly, the favor toward the rockets declined owing to the fact that Great Britain did not fight again on the Continent for almost a full century—or in North America at all—and partly to the development of the rifled cannon.

Rockets did not appear again until WWII, where the Russians employed the Katyusha rockets against the Germans on the eastern front and the Americans a variety of rockets both in Europe and the Pacific. The British and Canadians developed rockets also. Those of the Allies were favored on account of their economy, being less expensive than artillery. Ironically, the Germans took the rocket idea to the next level and rained down the V-1s and V-2s on London, whence the modern notion of warfare rocketry originated.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments