Interview by John Wukovits

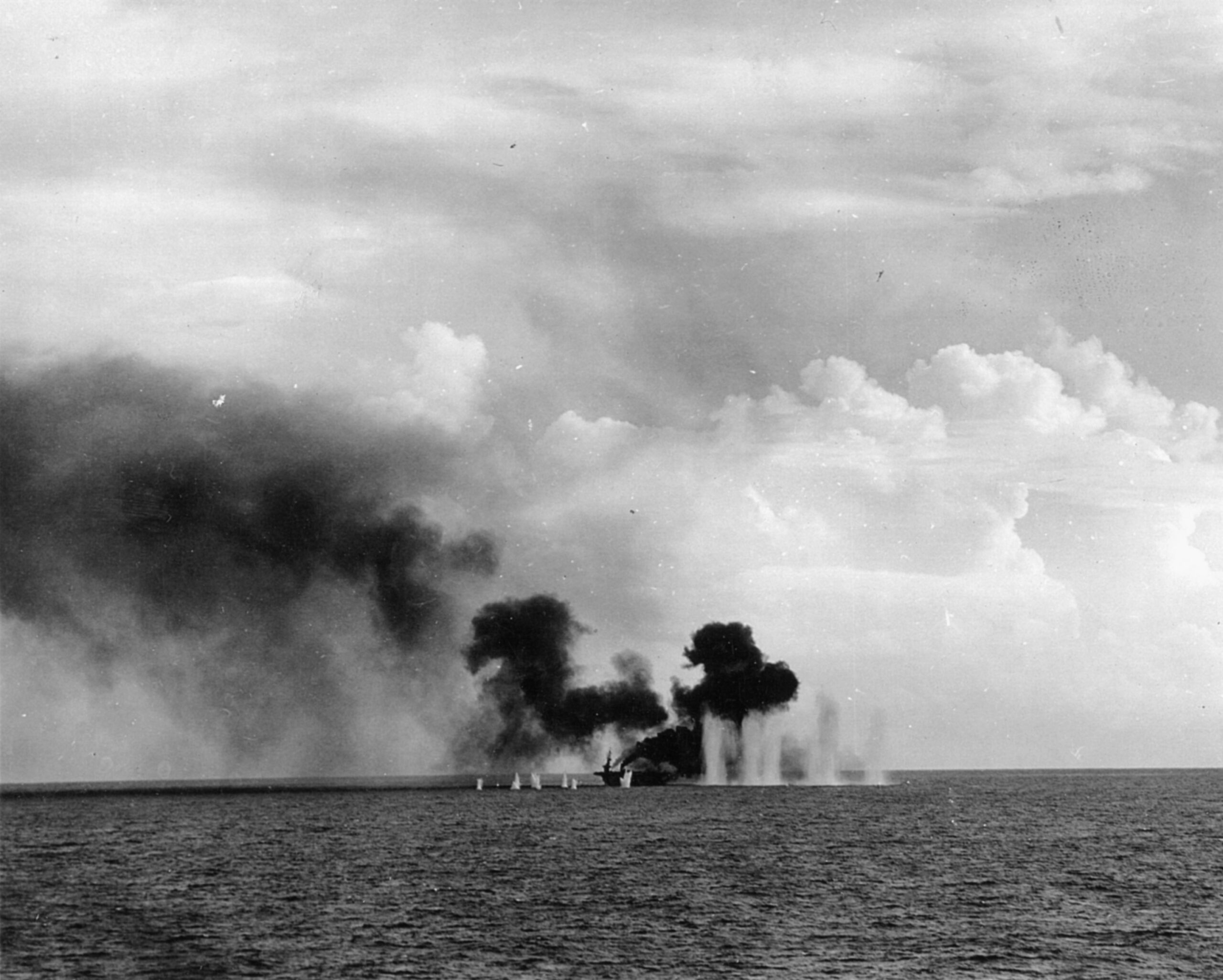

The 18-year-old seamen bobbed in the oily waters off the Philippine coast with other survivors of the October 25, 1944, battle. His ship, the destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts, had been sunk following an heroic charge straight into the huge guns of Japanese battleships and cruisers. The enemy ships had suddenly appeared over the horizon, and the Samuel B. Roberts had been one of several small U.S. Navy warships, that had engaged them in the apparently impossible hope of turning aside the vastly superior enemy force.

The Samuel B. Roberts and other Navy destroyers and destroyer escorts were serving as the screening force for Taffy 3, a task force that consisted of these vessels and several escort aircraft carriers. Taffy 3 was stationed off the American landing beaches on the Philippine island of Leyte, its aircraft providing support to the troops ashore and cover for the supply ships anchored off the island and unloading supplies. Had the Japanese succeeded in reaching the invasion force, they could have wreaked havoc on the defenseless transports and supply ships. On that fateful afternoon, all that stood between the big Japanese guns and the defenseless transports was Taffy 3.

In what became known as the Battle off Samar, one of several naval engagements that are collectively referred to as the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Japanese shells reduced the sleek American ship to a battered mass of twisted steel during 90 minutes of fighting. Officers and crew who had not been immobilized by wounds or killed in the frantic fighting had to abandon what had been their home for six months and enter the warm waters. For the first time since the battle’s opening moments two young seamen, drenched and exhausted, pondered their fate and the fates of their compatriots.

One of these, Seaman 2nd Class Jack Yusen, had avoided injury in the clash that just ended, but his ordeal was far from over. He was about to experience a three-day nightmare before his role in the naval struggle off Samar blissfully ended.

He discussed his experiences with historian John F. Wukovits, the biographer of Yusen’s task group commander, Admiral Clifton A. F. Sprague.

When and why did you enlist?

Jack Yusen: I was 17 when I enlisted. I was born and raised in Elmhurst, Long Island, in 1926. I enlisted because my father had a good friend on the draft board. It was getting close to my draft number, so he went down to speak to his friend. He told my dad that anybody who could breathe would be drafted into the Marine Corps in the next two months. My dad told me if I waited for the draft, that’s what I would get. I didn’t want that. I wanted the Navy, so I went down a few days later and joined the Navy.

What was more appealing about the Navy?

JY: My father’s brother served on the battleship USS Tennessee in World War I. He was not only a good uncle but a good friend of mine. He told me a lot about the Navy and said if I go into the military I should go in the Navy.

Was there any sense of patriotism sweeping through you when you joined?

JY: Oh, yes. With all your friends going, your neighbors, your family. We were very patriotic then.

Going away from home, then, what would it be that you most missed?

JY: I would miss my family. I had a younger brother, 5 years younger, and the neighborhood and the kids. But most of us knew we had to go in one way or another, and that was the right way to do. It was not looked upon as a great inconvenience. We had a job to do and let’s do it. You heard that all over. Let’s get the job over with and free the world and make the world safe again.

Did you have any opposition from your parents?

JY: No. They understood your number was coming up. Like all the families in America, they knew their sons and husbands were going in.

At age 17, did you have any plans for the future that the military interrupted?

JY: No, I really didn’t. All we heard was the war, and between my 14th birthday and 17th that is all we heard — war. You went to school, but everything was war, war, war. When we got in it in 1941 we knew guys like me would go in. I was hoping to graduate from high school and further my education, but I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. That came after the war.

I was a 2nd class seaman. My job was sonar, although it was called a sound man back then.

“What Are You Guys Looking At? Your Ship’s Over Here!”

You joined the Samuel B. Roberts in Boston. What do you recall of your first sight of the ship?

JY: I was stationed at a holding barracks, waiting to be assigned to ships. They were building so many ships in 1944 that they needed firemen for the DE’s. They called my name and about 13 others, and I was told, “You are assigned to the Samuel B. Roberts, a destroyer escort. Get your gear and get down to the dock.”

A truck took us to the Boston Navy Yard, and as we approached there was a huge, huge ship in drydock. It was a British cruiser, but we did not know it. We saw the big guns and thought it was our ship. “My God look at that,” we thought.

The guy that drove us over, a petty officer, said “What are you guys looking at? Your ship’s over here!” We looked at the other drydock to the right, and all you could see was the radar. It was such a small ship. We kept looking at the Samuel B. Roberts, back to the cruiser, back to the Samuel B. Roberts, etc.

Did you go right aboard ship?

JY: We carried our seabags onto the gangway and got on. We saluted the flag, then the officer of the deck, and walked down the gangway. They took us down to the galley to get us squared away. Then we were taken to the wardroom to meet Commander R.W. Copeland. He said, “Have these fellows been paid?” When he heard no, he said, “Let them each draw $10, and give them liberty tonight.” We weren’t even on the ship a couple hours, we didn’t even have our bunkers assigned, and here we had liberty.

Did that endear you to Copeland?

JY: We thought he was great. He told us to work hard, do our job. He was a good skipper.

Your time in Boston, you must have begun to form an opinion of the officers and crew.

JY: Yes. As soon as we started out to sea, that’s when the crew came together. The crew was a great bunch of guys. Copeland was big on drills so that we’d be ready for anything.

How many drills a day might you have?

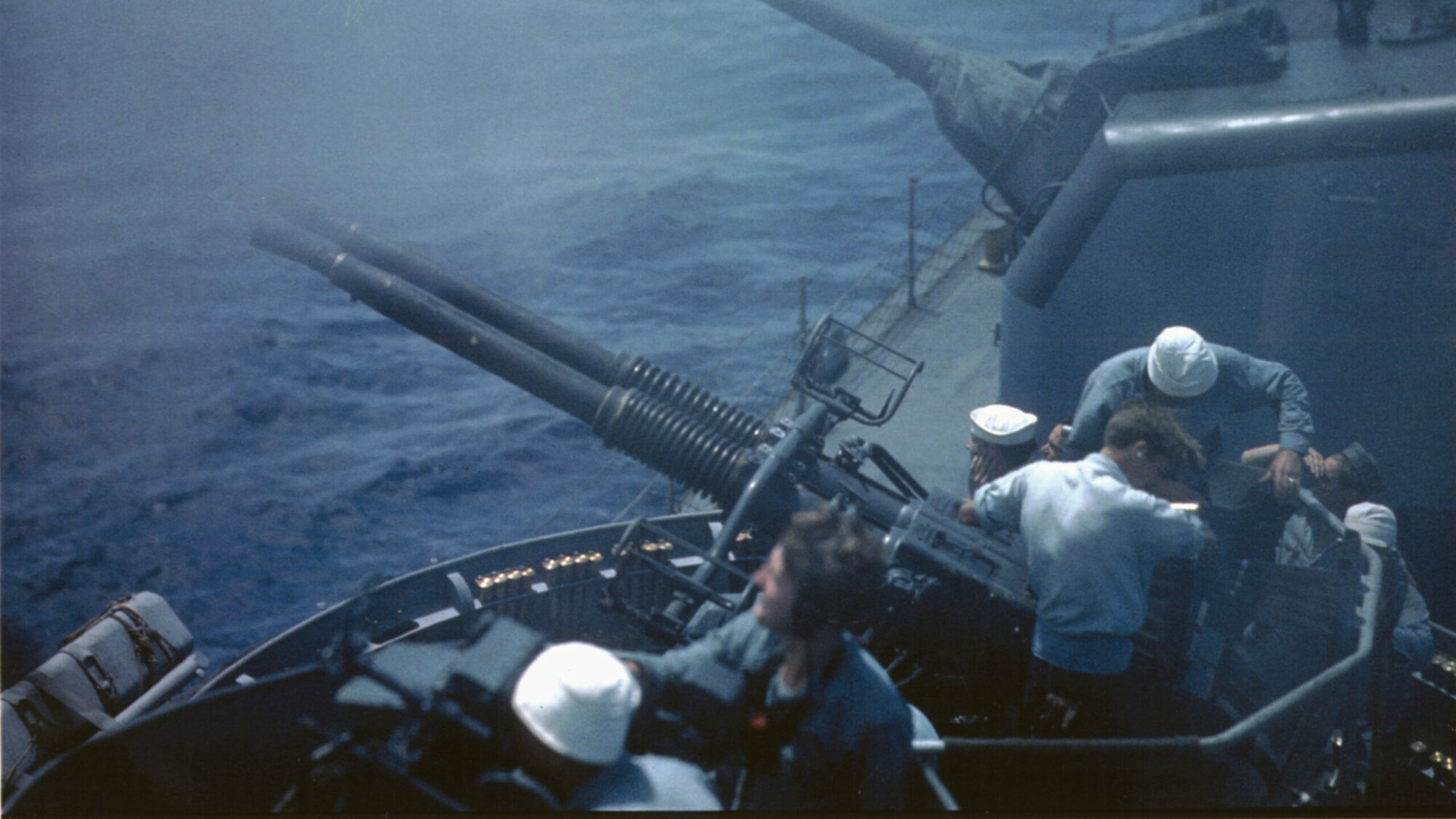

JY: Copeland would have them at any time. You could be on watch—mine was Sky-1, which was the 20mm on starboard side forward—and the officer of the deck would suddenly shout out, “Sky-1, stand by for a drill. Sky-1 load. Pick up dive bomber coming in on starboard quarter.” General Quarters would be for the whole ship—all man your stations. We would shoot at sleeves.

We hit a whale shortly after Boston. We thought we were torpedoed. I was making my bunk, and it shook the whole ship like being hit by a torpedo. The whale hit into us—boom! I ran up on deck with the rest of the guys with our life jackets. You saw blood, pieces of meat on the fantail.

We went into drydock to fix the shaft and propeller. The ship had been painted and prepared for Atlantic duty, but because of the whale we had to return to Boston for repairs. While there they needed more ships in the Pacific, so the ship was repainted camouflage and we were assigned to Pacific. Fate! Then we headed to the Panama Canal.

What specific steps did Copeland take to create good morale?

JY: He was a good skipper who demanded excellence from officers and crew. I thought we had an excellent bunch of officers. I thought every one of them was great. They were stern, and you had to respect them, but that’s part of it. They treated us right.

Was the ship representative of all portions of the nation?

JY: Yes. Most were from the Eastern Seaboard, a few from out West. When you come on your ship — I don’t care what kind it is or how large or small — that’s your ship and you’re proud of it. You go downtown and tell everyone else what ship you’re on. You’re proud to be on it.

Was going through the Panama Canal a unique experience for you?

JY: That was really exciting. I recall two things. One, how the armed forces guarded that place. It was so important. Can you imagine if we had to go around South America or India? The locks are unbelievable. Going through them, everywhere you looked you saw antiaircraft guns and planes flying.

What do you remember about the trip from Boston to Pearl Harbor?

JY: When we reached the Pacific from the Panama Canal, something happened. We kept looking at the water, looking for Japanese. We were really in the war now. Coming down the coast from Boston, nothing happened. I was standing on the deck on my watch looking out over the Pacific Ocean and I’m telling you, I was looking harder than when we were in the Atlantic. That’s where our war began. Now we’re really in it.

Some of us talked about that feeling. It just made you feel different. The minute you left Balboa, boy I had a whole new respect for the service.

Were you anxious to get into the fighting?

JY: Well, I don’t know about that. We knew we had a job to do. Another thing I noticed once we entered the Pacific: our training started harder. More training. We had little time to relax. You were four on, eight off, four on, eight off. Off did not mean off, I had a job to do on the motor whaleboat.

Would you see Copeland every day?

JY: He was up in the bridge and CIC most of the time. However, every once in a while he’d walk the deck. I remember one time we were on deck off watch talking and he walked up. “Hello boys. Take it easy. At ease. How’re you boys doing tonight?” He did not stand on formality when he was doing that.

What are your recollections of Pearl Harbor?

JY: We arrived in the latter part of June. When we first arrived there, of course, all of us were in awe of what took place on December 7, 1941. To just be there on the scene where the war started, everybody on deck was quiet. All you could hear was the water going by as you approached. There wasn’t too much to see at that time as far as the havoc wrought on December 7. I just remember a lot of ships, all kinds of ships there—aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers. Must have been 50 or 60 destroyers. [This] was my first indication of the kind of might we had building up.

Did anyone mention that there was no way the Japanese could defeat us?

JY: We were feeling very good about the war, at least I did. I didn’t think there’d be too many more battles.

Were you eager to get into action?

JY: I don’t think I was eager, but I was ready. The guys on my gun, the 41 gun, were serious about their jobs. We were ready to do whatever we had to do. One month before our ship sank I was transferred to sonar room.

“One Evening, Before You Knew it, They Were Rolling the Cans off the End of the Ship, and the Explosions Came.”

Was the crew anxious to get into the fight?

JY: I think a lot of guys were—some of the fellows who lost family members. I wasn’t anxious for it, but then in my mind I was always wondering what it was going to be like to go through an air attack or a submarine attack. You never even thought of a big surface engagement! That was the farthest thing from everyone’s mind. DE’s [destroyer escorts] were built to protect other ships from submarines and air. We never thought we’d go up against a heavy concentration of Japanese fire.

Was there a strange fascination about what battle would be like?

JY: Oh yeah. I had a bunk on the starboard side up forward of the bow, and I lay there and by putting my ear to the bulkhead I could hear the water going by. I would sometimes wonder what would happen if a torpedo hit us. But most of the time you would be too busy to think like this.

What did you most like about Hawaii?

JY: The water is so beautiful. Also, I was impressed with the amount of firepower. I went on liberty on Waikiki Beach, and that was impressive. It used to be only the rich would be walking that beach.

We weren’t in Pearl Harbor that much. We’d have target practice at a plane pulling a sleeve. We were also operating with an American submarine and going through exercises. We’d go out in the morning and come back late afternoon. The guys on liberty would be heading back to the ship by the time we returned from exercises.

We were ordered to take a convoy with other DE’s, maybe 15-20 ships, to the Marshall Islands, Eniwetok. That was our first convoy. It was about a week trip. That is the time we had a submarine contact. One evening, before you knew it, they were rolling the cans off the end of the ship, and the explosions came. We dropped about 10-12 depth charges, and that ship rocked when they exploded. We never got a confirm on it.

Did you have a feeling of more seriousness, like when you entered the Pacific?

JY: Oh yes. Then we knew we were in the war zone. That contact gave us that feeling. My reaction wasn’t that, uh, oh, we could get hit any moment. It was more that we were going after the enemy and here was our chance and this is great, we’re going to get a shot at them. We’ve got to protect these other ships out here.

Did Copeland conduct drills while in convoy?

JY: Yes. He drilled all the time. We didn’t mind it because we knew how important it was.

We got back to Pearl Harbor for about 5 days. Then we went on other convoys. Finally we were told we were a part of the Seventh Fleet [in the Southwest Pacific]. That took us 10 or 11 days to get there. This was the trip where we had the crossing the line ceremony.

Can you describe the ceremony?

JY: All the guys who were pollywogs became shellbacks. If you’re a mariner, you’re called a pollywog. A piece of nothing. A shellback is a mariner who went across the equator. A lot of initiation, and it’s tough, I mean it is tough! Oh man, they worked us over! We had about 20 guys who were shellbacks, and here we are sailing with the convoy, through enemy waters, having this big program. All the ships were doing the same thing. You always kept a crew on duty, manning some guns, and the guys going through it, once they were through they would relieve them. And oh boy!

We had to endure, all day long, getting orders. They made me and another guy get down on our stomachs and push a potato up to the bow. You would have to get your heavy pea jacket on, go to the bow and blow the horn. You had to meet the royal barber and the royal baby. The royal barber would cut your hair, and while he was doing it someone else would shock you. They paddled you and were always wetting you down with water hoses.

The last thing was a canvas, maybe 50-60 feet long, sewn together. They put the garbage in from the last 4 or 5 days, and you had to get down on your hands and knees and go through the canvas. While you doing it, they were paddling you. Once you made it through, you were a shellback.

Was that the standard procedure on all the ships?

JY: Yeah.

Would there be some instances of where one person had a grudge on another and took it out on him?

JY: Yes. As a matter of fact a couple of guys went to blows, but it was quickly over. It was a lot of fun. The crew paddled Copeland, but they did not bear down hard on him.

We had our division commander aboard ship at the time. One of the shellbacks knocked his hat off and into the water. One guy refused to go through it. He was isolated from then on. He was afraid, I guess. He was sort of a guy who got into trouble a lot.

“We Were Rolling and Pitching and Hanging on for Dear Life Trying to get Inside.”

Did you ever regret not being aboard a larger ship?

JY: No. Once I was on the Samuel B. Roberts I became a tin-can man, a tin-can sailor. We were the greyhounds of the fleet. If the fleet wanted a job done, call on the destroyers. That’s how I feel about it to this day. You know what, John, every guy feels this way.

Do you remember entering Seeadler Harbor?

JY: What a huge harbor! As far as you could see, were ships, not only warships but supply ships, hundreds and hundreds.

What was your reaction when Copeland told everyone to get their personal affairs in order?

JY: I remember him saying something over the loudspeaker about this, to write letters home, etc. We knew we were going somewhere. The word got around that it was the Philippines. Hearing his announcement did not affect me too much. I wrote a letter, but you couldn’t say much.

What about the typhoon on the way to the Philippines?

JY: That was something! I couldn’t believe that thing. I was on watch at noon that second day, and when I got to Sky-1, when the ship was in the trough, it was like looking on both sides a wall of water as high as our radar’s mast. Copeland gave the word for everyone to go inside. We were rolling and pitching and hanging on for dear life trying to get inside. Waves were coming over the bow. I must have had two inches of salt water crusted on my face.

We got inside and latched the doors. By late afternoon and evening we were taking rolls so that no one could stay in the bunks, the galley shut down because they couldn’t cook. If you were standing on the deck, let’s say, and she rolled to the starboard, you would stand on the bulkhead. Then it would come back the other way. All the boys will tell you, we felt the ship was going to turn over. We were all screaming, and it was terrible! That went on for two days, and guys were getting seasick. We were getting banged around. But our little ship came back.

The front 5-inch gun had been turned to the port to protect it, and the mount covering on the starboard side was caved in from the tons of water coming in. We heard some of the airplanes were ripped right off the escort carriers. Up until that time, that was the scariest experience of my life. It amazed me in the group that we were in, spread out over miles, that not one ship collided. How the hell did we avoid that?

Encounter Off Samar

Yusen and his shipmates headed toward history’s largest naval encounter. As part of the escort carrier task group, Yusen’s small ship was designed to provide protection for the escort carriers. No one had a clue that they would soon be involved in a titanic struggle for survival against some of the enemy’s most potent warships. Their ship was neither designed for, nor expected to become involved in, a major surface action.

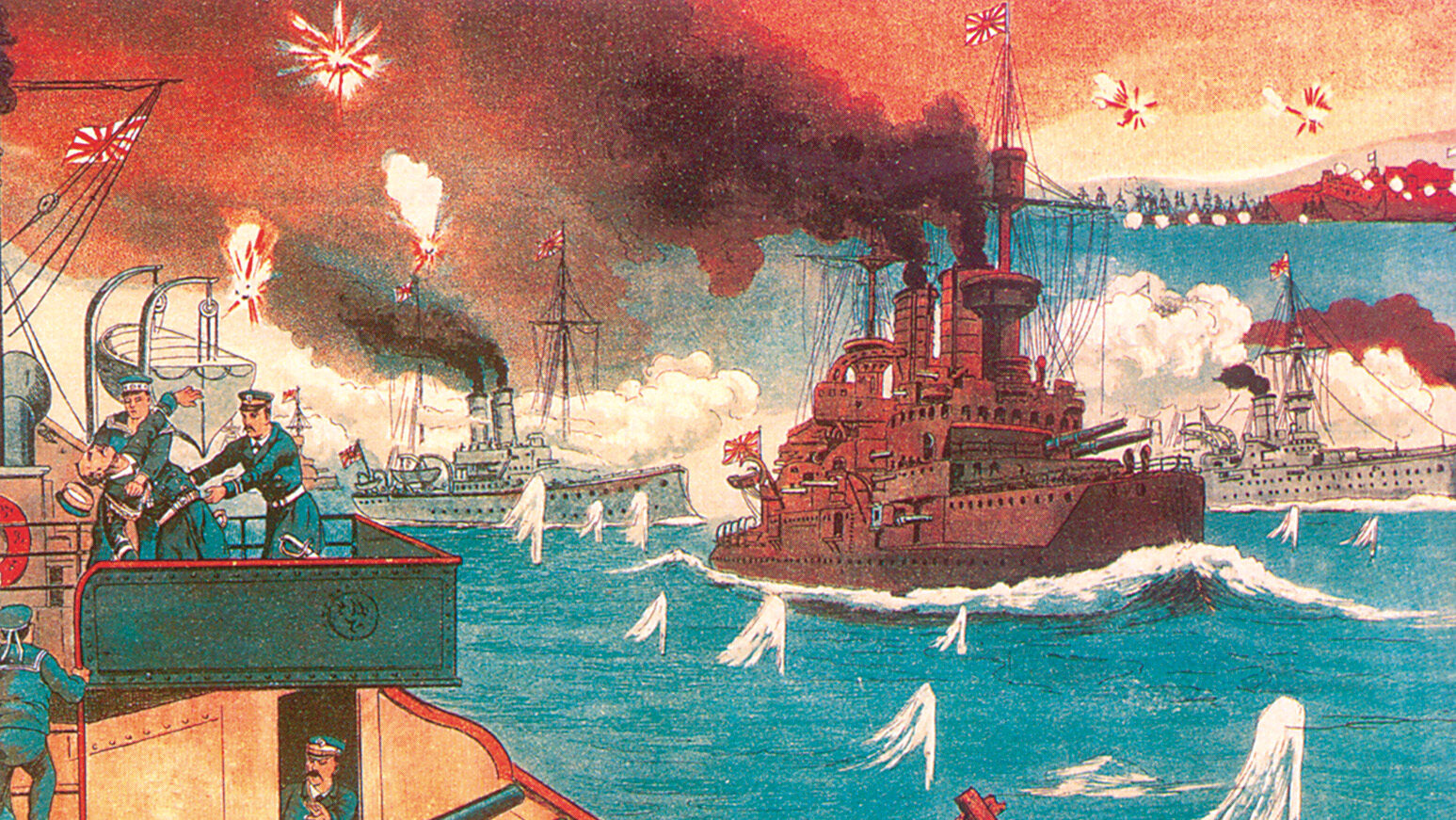

The Japanese had other ideas. In an intricate three-pronged assault, they intended to draw away Admiral William Halsey’s fast carriers to the north while other Japanese forces steamed in and attacked the American landings to the south at Leyte Gulf. Admiral Clifton A.F. Sprague’s 13 ships of Taffy 3 stood between the most powerful Japanese force and Leyte Gulf. If the Japanese were to succeed, they had to get past Taffy 3, steaming off the island of Samar. Yusen faced quite a surprise in the early morning hours of October 25, 1944.

“This was Our First Major Action, and I Thought I Would Survive at First. A Few Minutes Later I Changed My Mind.”

What was the first inkling you had that something was about to happen off Samar?

JY: We knew the night before that something was going on, although we had no idea it would end up coming our way. We could see flashes and hear the sounds from Surigao Strait. We thought at first it was an electrical storm.

I was just being relieved when general quarters sounded. My battle station was at the forward 40mm gun, in front of the bridge. Captain Copeland came on the speaker and said, “Men, a large Japanese force is approaching 18 miles away. We are outnumbered but we will do our duty.”

I was on the 0400 to 0800 watch, and when we went to GQ I thought, “My God, that’s the Japanese fleet approaching.” Boy were we surprised! We couldn’t believe it. We were so young that when we heard they were 18 miles away, we thought we could easily outrun them. Then the salvos straddled us and we realized the seriousness of the situation.

He (Copeland) signed off, and just then we heard the Japanese guns 18 miles away boom. The shells passing overhead sounded like freight trains. Man, did they drench us with water from near misses! I think they were aiming at the [escort carrier] Gambier Bay. Ten minutes later we saw the fist masts coming hard at us.

Admiral Sprague gave the signal for us to lay smoke. We went around the Gambier Bay twice to cover her with smoke. We then formed for a torpedo attack. We were right behind [destroyers] Hoel, Heermann, and the Johnston. Shells hit real close and burst in Technicolor. One shell hit our bow, went right through both sides, and exploded in the water. We closed to within 4,500 yards of a cruiser and let three fish go. I was right behind the bow in an exposed position, so I could see everything. One of the torpedoes blew off the cruiser’s stern, and we cheered like we were at a baseball game, although we were scared.

We dueled cruisers with our 5-inch guns. Copeland did everything he could to evade being hit. He chased salvos, ran into rainsqualls. Our 5-inch gun hit the superstructure of the cruiser, although the guns could do little damage. We then took two big hits. A total of about 26 hits got us altogether. In two and one-half hours we shot about 600 rounds of 5-inch shells. We ran out of regular shells, so we began shooting star shells. A cordite smell was all over and smoke covered everything. The Japanese ships were so close you could see their turrets turning.

Did you expect to survive?

JY: This was our first major action, and I thought I would survive at first. A few minutes later I changed my mind. They got so close to us in the next 45 minutes. When Sprague ordered us to attack straight at those Japanese ships, I knew we were in big trouble. You could hear shipmates saying things like, “We’re outgunned! Those are cruisers, and we’re only destroyer escorts, and we are in bad shape.”

But you push those thoughts out of your mind and get into the combat. You become too busy with the fighting to consciously think of getting hit and killed. Toward the middle of the battle, when those Japanese ships were so close and we took hits toward the back end, we realized this was for real. A Japanese cruiser was lying off about 8,000 yards, and we could see the enemy staring at us and firing. We could see the crew leveling the guns and the turrets turning toward us. They had been shooting over us at the carriers, but when they saw us shooting at them with our 5-inch guns, they slowly turned the turrets toward us! We were a bull’s-eye and felt so vulnerable. I had a grandstand seat in the forward 40mm right in front of the bridge and right behind a 5-inch gun, and I felt very exposed. We took many hits around us.

I recall one hit going through our bow and really shaking the ship. The bow came out of the water and knocked me over. We could feel major hits rocking and rolling the ship, but we could not leave our posts and take a look, of course.

We were getting hit, and we knew guys were getting hammered back there, but we were thinking of our own area and had our jobs to do. You can’t think of other things. It was very noisy. It’s amazing that none of us on the forward gun got hit.

I feel Sprague did a hell of a job in protecting his carriers and sending us against the Japanese. That was our job and what he was supposed to do. We were the expendables, and that’s what it was all about.

Tell about going into the water.

JY: Someone from the bridge yelled, “Abandon ship! Abandon ship! All hands abandon ship! Every man for himself!” I never worried about survival or thought about it until I got the order to abandon ship. Then I knew this was for real.

When the order came, Bud Comet, who was on my 41 gun, told me to go down to the port side and get near the raft. I came down on the main deck port side, but there was nobody there. Almost 99 percent of the crew went off the starboard side, the high side. The port side is where we had that main hit back there that opened us up, and we were listing to port.

While I was standing there, the ship took more hits and things exploded. One guy, the ship’s cook 3rd class, came up and said we got to get out of here. I told him to hang on for a minute because I was waiting for the raft to be cut down by Comet. Then we saw a guy coming from back aft up to the port side toward us. This sailor came by me, and there was nothing where his right shoulder and arm should be—there was a big hole there. Nothing was there. He just walked past the cook and me. To this day I don’t know who that man was.

Finally I looked up and the raft was there. The cook and I jumped in the water, but water that was being sucked in through a big hole in the ship’s side started dragging us in. We were close to fire, and the cook and I mustered all the strength we could and we got around the pool of oil and fire to the back end of the ship. We were the only guys there. The water was covering the ship’s name on the stern. We headed toward the starboard side. I didn’t remove my shoes when I went into the water. They told us to keep them on because sharks can see white feet.

I looked up at the ship and saw guns back there all blown apart, torpedo tubes all gone, nothing but a big hole back there. “My God, half the ship is gone,” I said. We had only our life jackets on, and a few minutes later Bud came by with the raft.

About 20 minutes later Bud came by with the raft and picked us up. The only guys who went off the port side that I know of were the cook, Comet, me, and the two or three men Comet picked up with the raft.

Did you see men go down with the ship?

JY: Yes. As we abandoned ship I looked to my left and saw two men sitting with their backs against a bulkhead with their knees up. I don’t think they were wounded. They were just sitting there. I don’t know if they were stunned from explosions or hurt, but they just sat there and went down with the ship. Other guys who were wounded and couldn’t move also went down.

What was your reaction to seeing the ship disappear?

JY: We watched the ship lying over to the port side, then lift her bow straight up and sink. This is not happening, I thought.

“Our Ship Sank About 15-20 Minutes After I got to the Raft.

What happened then?

JY: We swam to a raft about 100 yards from the ship. About 10 minutes later, Bud Comet, on another raft, joined us. Comet had gone into the huge hole to get some guys out. We had Bud tie his raft onto ours, and we tried to get some discipline. We were on the raft just shy of 60 hours. There were 50-60 men in and around the two rafts. The wounded were put in the rafts. We all thought we’d be picked up in minutes because of all of the other ships, but that didn’t happen.

Our ship sank about 15-20 minutes after I got to the raft. It went straight down—nothing but bubbles left. Guys were either very quiet or sobbing. That ship was our home. There’s something between sailors and their ship. When the Roberts sank I lost some money, about $60-$70, a watch, all my clothes, my seabag filled with winter stuff. All I had left was my identification bracelet. I still have it on my desk, still with some oil on it.

A Japanese cruiser started bearing directly down on us, but swerved about 60 yards away. One Japanese officer, the captain, saluted us as the ship passed by, and another guy was taking movie pictures.

What about during the night?

JY: Each guy in the water would help the guy next to him to stay awake by talking. With the sun down, it got terribly cold, and the wind made it worse. During the day it was just the opposite—very hot. The oil that covered us helped prevent heads from getting too sunburned.

We were getting tired because we had not eaten all day, had been through a battle, and now were in the water. One time I dozed off near dusk and floated away with my life jacket propping up my head. I was about 100 yards out when Comet wondered where I was. He saw me and swam out and woke me up. It was now dark, so the other guys kept shouting, “Over here! Over here!” to get us back to the raft.

What was the second day in the water like?

JY: The second day was terrible. The sharks came along, and we could see their fins. The sharks dove, and when you couldn’t see their fins you knew they were coming at you. It was such a helpless, useless feeling! At least during the battle we could do something. We men in the water would turn around so we faced the sharks, while the men in the raft grabbed onto us, and we would kick our legs to make splashes. The sharks didn’t like it, and it worked a bit. My legs got so tired I almost couldn’t lift them. The sharks would go out a ways then slowly start back in again. They got two guys. One guy’s leg was bitten off, and he was bleeding so much we had to cut him loose because his blood attracted even more sharks. He floated away, and the sharks went after him. He ended up giving his life. He was just about dead when we cut him loose, so we got a much-needed rest from the sharks while they occupied their attention with him.

The sharks were also following our rafts because they could smell the blood of the wounded. Guys would say, “Here comes another one!” when a shark was moving toward us. One shark came right by me. It was at least 12 feet long. I kept still because I did not want to annoy it. Talk about being scared! I thought, “This is it. I’ll never see my family.”

Conditions must have been horrible on the raft. What about food?

JY: All we had was some malted tablets. No food or water. We had to tell guys not to drink the saltwater. You’d hallucinate, and then you can die. Guys didn’t drink much on purpose, but the waves splashed us, or when we’d fall asleep we’d get mouthfuls. Some started to stab people because they were going crazy from drinking saltwater, so one man said let’s throw all the knives away. We did. We took them from the guys who were doing the stabbing. Only one guy who was wounded in our raft died, a guy who was burned very bad. He suffered the whole time.

While we were in the water, we tried to make our way to land. The second day we saw some mountains way off and thought we could get there. We never got there, which was good because Samar was filled with Japanese.

“The Ship Came Closer, and Through a Megaphone We Hear, ‘Who Won the World Series?'”

Did you ever lose hope?

JY: I thought after the second night that I would not survive another twelve hours. It was freezing cold, we had no water, food, or medicine. We were beat and trying to pull the raft. Guys were drinking saltwater and hallucinating. Guys said they were going below to get beans. It was really getting out of hand. Men were getting angrier because we were not being rescued. Some cried, prayed, sang hymns. I prayed that I would be able to see my family again. The last night we were so weak and could feel the strength going. We were all young kids and in good shape, but we weren’t prepared for this. We figured the rescue efforts focused on the carriers, and we were off the beaten track, away from the action, and harder to locate. The other guys, from the Gambier Bay and St. Lo, were more together, but we were on a tangent.

How were you rescued?

JY: I started to lose hope after that horrible second day. On the third morning, I thought that I could not go through another day and night. Someone that morning yelled, “There’s a ship!” Chambless stood on the raft, other guys held him, and signaled the ship with some civvies. The ship approached, and we saw the American flag. What a feeling! The ship came closer, and through a megaphone we hear, “Who won the World Series?” With all the oil we could have been Japs. We all shouted, “St. Louis, goddamn it!”

We got all the wounded guys up to the ship first, then us. We had to go up a long ladder to the hospital ship, and we were so weak I barely made it to the top of the ladder. A nurse and two orderlies grabbed me. Then I passed out. What a feeling of relief to finally get out of the water! They put a blanket around me, gave me some booze, and then I lay down on the deck and I was out.

I opened my eyes six or seven hours later, and we were in Leyte Harbor. While I slept, two Japanese planes attacked. Our fire drove them away, but I slept through all the noise. transferred to an army hospital ship in Leyte Harbor. I got most of the oil off me by showers, but oil came out of my ears for a month afterward.

When we were picked up and realized what had happened, that the Japanese turned back, we were angry. Where in hell were the rescue ships? Where were our own Taffy 3 ships? There were some hard feelings toward Sprague, but not a lot.

When did you know for sure that you had made it?

JY: I guess it was when we saw that ship coming toward us and we saw the flag. That night, when I was put on the hospital ship, I was sure I made it. The boys of the ship that picked us up removed our clothes to remove the oil, then wrapped us in blankets. We got clothes the next day on the hospital ship.

I had salt water poisoning in my legs, and my ears were blocked by the oil. I don’t know how I didn’t get hit by shrapnel, but those were the only things I had.

What happened after you were rescued?

JY: I spent two days on the hospital ship, then I was sent to Hollandia, New Guinea. I was in an army camp there for two days. The former luxury ocean liner, Lurline, took us to Australia. From there, in 14 nonstop days, we got to San Francisco without any escort. By the time I got back to San Francisco on December 1, 1944, I got my weight back to about 152 from the 101 it was. Dehydration and all the activity in the water made us lose so much weight.

Two days before the Lurline arrived in San Francisco, we all met with Copeland. He said he wanted another ship and we all said we wanted to be with him. We got shore duty instead.

Joe Lecci, from Brooklyn, was killed in the battle. He told me if anything happened to him to go see his wife. When I got home on my leave, I saw them—his brothers and wife. She was pregnant but could not come down from the bedroom to see me because she was so distraught. Lecci was sort of my older brother. He was a cook. I was home about a week when I went over and visited. They couldn’t do enough for me with the wine, etc. He had three brothers, and aunts and uncles and cousins came over when I visited. They were all there to see me. His battle station was the port side. He took a shell blast right into his area and did not know what hit him. I told the family that he died instantly. Lecci must have been about 27 years old.

Around 1994, I got a call from Joe’s son, Joe Lecci, Jr. He came to Seattle, and I met him. When I walked into the lobby I thought that Joe came back to life.

What has being part of that battle meant to you?

JY: For 38 years I never said much. My family, friends, etc. knew, but I let it slip my mind. It was over, until I learned that Copeland was having a ship named after him. That started it. All of us survivors found out what Copeland and the ship had done in the battle, and I felt so proud that we didn’t lose the battle and what we had done in it. We decided to get together for the commissioning of the Copeland and that we would honor the guys who didn’t make it. In 1980 we started the Samuel B. Roberts Survivors’ Association. There were 41 guys at the first reunion. We had a story to tell, and we wanted to do it the right way.

The crew was a bunch of great guys. The officers were exceptional, and the captain was very stern but fair, and exceptional. When this action came every man did his job. In meeting these survivors 38 years later, they all had had a wonderful life, nice children, great wives. That’s one of the things we always talk about—we survived, and now we’re going to live right, raise our families, and do it the right way.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments