By Keith Milton

With muffled oars, the longboat sent by Admiral Horatio Nelson glided silently through the darkness of the enemy’s anchorage—at one point its sailors were close enough to the Danish ships to overhear the conversations of the sentinels. As the men in the boat made their way along the row of anchored vessels, they sounded the channel’s depth with long poles, rather than the usual lead weights that might make a splash.

As Nelson’s men determined the depths, they placed a string of buoys to mark the channel, replacing those recently removed by the Danes. Then they returned to their own waiting warships, to the impatiently waiting one-armed and one-eyed admiral, hero of the Battle of Aboukir Bay. Coming three years later, this battle—the fight he would later call his “severest”—would begin in the morning and become known as the Battle of Copenhagen.

In a way, the Danes and the English who were to fight in the morning were reluctant adversaries. Their confrontation was dictated by attempts at neutrality that had fallen victim to the shifting alliances of the European powers as Napoleon bullied and blazed his way through European history.

The role of neutrals in wartime had supposedly been subject to custom and international law for centuries; in actual practice, however, these customs and laws are shaded, bent, even blatantly ignored as circumstance dictates. A neutral whose sympathies were known to be with one of the belligerents was not likely to be treated kindly by the other, no matter what the accepted rules. Denmark found herself in this position in 1800 during the First Napoleonic War between England and France.

The little Scandinavian country had managed to profit from trade with both sides, and was in essence a true neutral, until Napoleon suffered the loss of most of his fleet to Nelson at the Battle of the Nile (also called Aboukir Bay). Bonaparte realized that even though he was all-powerful on the Continent, he could not hope to invade the British Isles until he rebuilt or replaced his fleet. He therefore brought pressure on Denmark, which at that time included the Province of Norway, and her sister-state Sweden to restrict their trade with Britain. Such restriction of trade was bad enough, but Denmark also guarded the entrance to the Baltic. If Britain were shut out of the Baltic she would lose a great deal of the timber, canvas, hemp, pitch, and iron she needed for shipbuilding.

The Danish Prince Royal, acting as Regent for his aged and ailing father, Christian V, realized that Napoleon could invade and take over his country almost at will. He had little choice but to comply with the French leader’s demands.

This was a blow to Britain, though not insurmountable. She knew that she must keep up her Baltic Sea trade because it was the main source of the naval stores necessary to maintain her fleet. She engaged other carriers, and did much of the carriage herself, but with changed attitude toward the Scandinavians.

Then, on August 8, 1800, a British blockading squadron encountered a Danish convoy off Ostend, consisting of six merchantmen escorted by the 40-gun frigate Freija. The convoy was halted by shots across the bows, but the Danish commander signaled his refusal to allow a search for contraband. He soon backed this up by firing on a British longboat sent to conduct the search. A sharp action followed, and the outgunned Freija was forced to strike her colors. The convoy was taken as prize into Southampton for adjudication.

The event proved an embarrassment to the Admiralty, which had been instructed to prevent any further deterioration in relations with the neutrals, so the British allowed Freija to rehoist her flag while an envoy was dispatched to Copenhagen to treat the matter. The upshot was a British apology, the repair and reprovisioning of Freija at Admiralty expense, and the release of the entire convoy. British acquiescence could scarcely go further, and it seemed for a time that the matter had ended.

But now, another player entered the scene, one whose actions set at naught all the British efforts to placate the neutrals. Paul I, Czar of all the Russias, son and successor to Catherine the Great, had newly come to power and was anxious to flex his muscles. He was, moreover, a great admirer of Napoleon, due mostly to the long string of military victories racked up on the Continent by the First Consul of France.

Bonaparte, for his part, was more than a military genius; he was also an astute politician and a good judge of human nature. He conceived a plan whereby he might play upon Czar Paul’s vanity and thus gain the Russian and Scandinavian fleets for his use against Britain. On paper, at least, 64 sail of the line would be twice what he could build in a year and would more than replace his Nile losses.

Bonaparte’s original grand design for the conquest of the Mediterranean—and eventually India—had been thwarted by Nelson at the Battle of the Nile, but all was not lost yet. The first step in this plan had been the capture of Malta, which Napoleon had accomplished rather easily. Without his fleet, however, he was wise enough to know he would be unable to hold the island. It was, in fact, already under siege by the British Mediterranean fleet and its fall seemed imminent. Napoleon thereupon ceded the island to Russia, and so informed the Czar. Paul, by dint of his office, was titular head of the Grand Knights of Malta, and so when the island fell to the British siege several weeks later, the Czar demanded possession. The British refused his demand, and in retaliation Paul seized all British shipping then lying in Russian ports. This in itself would have been cause for a declaration of war, but Britain, hard-pressed with her far-flung blockade of Continental ports and the need to protect her own shores, decided on forbearance.

Not content, Paul then pressured Denmark and Sweden to unite with him in an Armed Neutrality Pact which would, in effect, deny the Baltic Sea to British ships and pierce at will the Continental blockade being maintained at such high cost by the British fleet. Britain was left with no selection—the Admiralty was instructed to mount an operation in the Baltic with all possible speed, and to destroy the three fleets—Danish, Swedish, and Russian—piecemeal, before they could unite and become the engine of Britain’s destruction.

Their Lordships assembled the largest fleet that could be spared without completely denuding the Home and Channel fleets. It consisted of 26 sail of the line; 12 bomb vessels; 7 fast frigates; and 11 sloops, brigs, and other auxiliaries. They were gathered at Great Yarmouth to be resupplied and made ready for sea.

The wide expectation was that command of the expedition would be given to Admiral of the Blue, Sir Horatio Nelson, Hero of the Nile, and well known as one of Britain’s finest sea commanders. But it fell instead to Admiral Sir Hyde Parker, several years senior to Nelson, a wealthy nobleman in his maturity with an undistinguished record. Nelson was disappointed at being named second in command. He, too, thought his spectacular victory in Egypt would entitle him to lead. He had served under Parker before and was not impressed.

Nelson had just returned from Naples and felt the cold of the northern latitudes keenly. He had complained of ague and his old wounds were bothering him. In truth, he might have been excused from the mission entirely had not their Lordships felt it necessary to get him away from Britain in order to quash the scandal surrounding him and Lady Emma Hamilton. She and the elderly Lord Hamilton had accompanied Nelson on his return to England from Naples, and their liaison was the talk of Britain. The scandal had caused the failure of Nelson’s marriage, and had he not been a national hero, he would probably have been cashiered.

While laying out the operation, it was decided to bypass Sweden, since her fleet was the smallest of the three “neutrals,” and it was known that she was only a half-hearted participant in the alliance. Russia was the main enemy, but to sail up past Riga to Reval and engage the ice-bound half of Paul’s fleet would leave the rather considerable Danish Navy in the rear and run the risk of being bottled up in the Baltic. Clearly, the place to start was with the Danes at their main base and capital at Copenhagen.

By now the fleet was ready, but Parker found excuses for delay while Nelson chafed and urged haste. Finally, in exasperation, Nelson wrote privately to his friend, the Earl of St. Vincent, recently created First Lord of the Admiralty, and St. Vincent in turn ordered Parker to weigh anchor and proceed on the next tide. The fleet got underway and came to anchor just outside the Sound on March 20, 1801, to await word of a last-ditch diplomatic effort to reach accommodation. When word was received on the 22nd that the Danes would not agree to British terms and were, in fact, preparing the defense of their capital, the die was cast. Parker found fresh excuses for delay while Nelson chafed and fumed again under his commander’s indecision. He even took the almost unprecedented step of advising his commander-in-chief.

“The more I have reflected, the more I am confirmed in opinion that not a moment should be lost in attacking the enemy; they will every day and hour be stronger; we shall never be so good a match for them as at this moment.” Even this breach of naval etiquette failed to goad Parker into action. It was plain that he still had hope of settling the matter without bloodshed. When his efforts to negotiate with the Danish commander of the batteries at Elsinor Castle failed, however, Parker at last decided to act. He moved the fleet toward the strait and, as he approached, the batteries on the Danish side opened fire just as promised. Parker then signaled his fleet to move out of range and hug the Swedish side. The Swedes stood to their guns, but held fire, and just at dusk the British fleet came to anchor south of the island of Hveen, north of Copenhagen.

Nelson had no illusions about the fighting qualities of the Danes. Their seafaring heritage stretched back to Viking days, when they had overrun England herself, and had for 50 years been able to keep Danish kings on the British throne.

The reconnaissance ordered by Parker in the fast frigate Amazon confirmed the opinion that the Danes were ready—Parker’s stalling had precluded any surprise. The northern approach to the harbor of Copenhagen was guarded by a formidable twin-battery fortress built upon pilings and known as the Trekroner (Three Crowns). It mounted 66 heavy guns. In the harbor mouth itself, the Amazon found a half-dozen warships of various sizes with yards crossed and ready to move where needed at a moment’s notice.

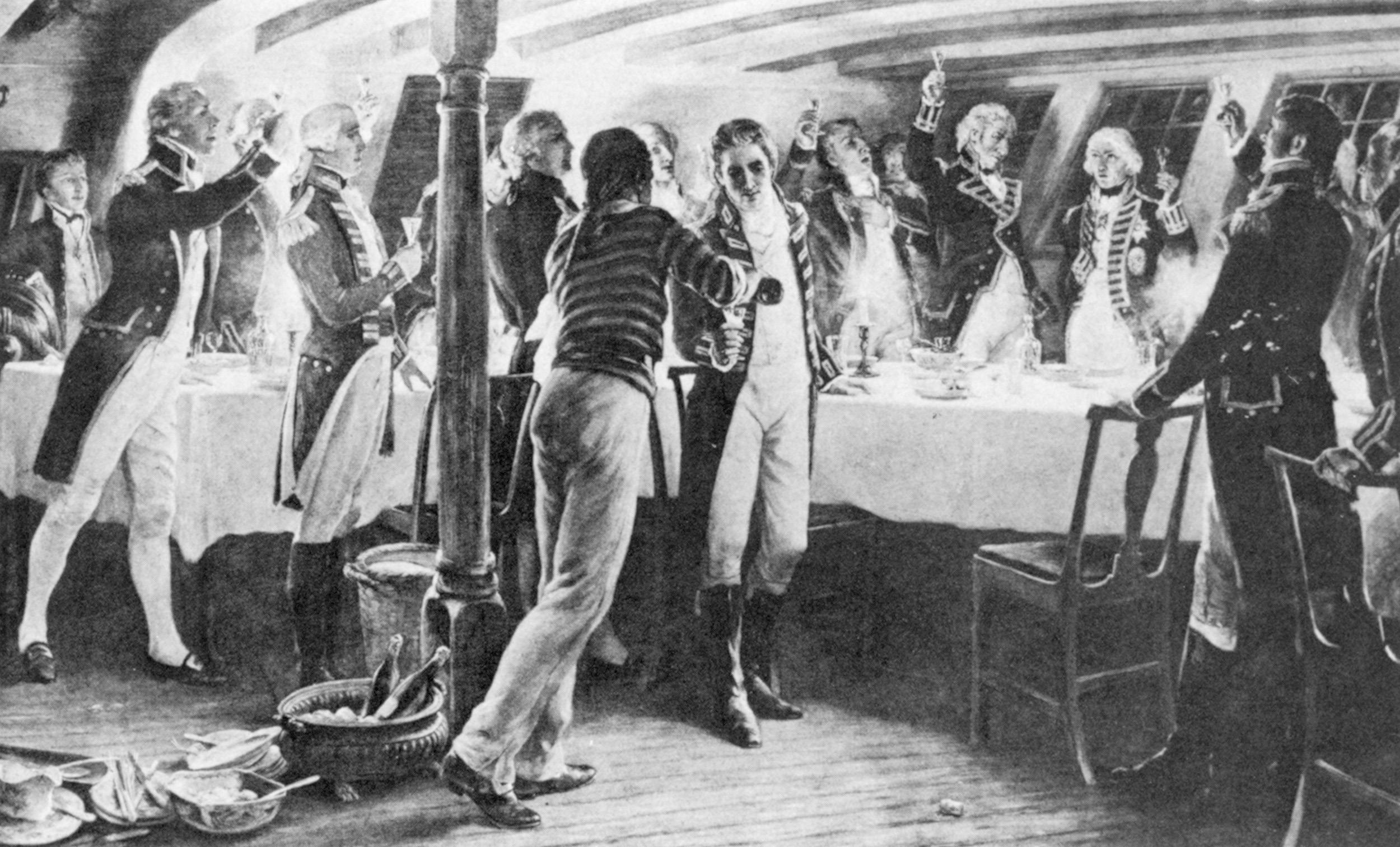

The southern approach was protected by 18 Danish ships anchored in line. Most were merely hulks, and many did not even have masts, but they were all armed and manned. All were double-anchored with springs and were close enough to each other and to the Amager Shoal so that their line could neither be pierced nor flanked—the tactics that Nelson had used to defeat the French at the Battle of the Nile would be of no use here. During the council of war that Parker now called, Nelson offered to take on the Danish line with 10 sail of the line, while Parker held the northern approach with his heavier ships. Parker agreed to the plan and added two more to Nelson’s division, giving him 12 of the line, plus six frigates and five gun brigs.

On the afternoon of April 1, Nelson’s division weighed anchor and sailed south down the outer channel, coming to rest just off the tip of the Middle Shoal about three miles south of the end of the Danish line.

After dark, Captain Thomas M. Hardy, who was acting as Nelson’s chief of staff, took his longboat with muffled oars and rowed the length of the enemy line. He surveyed and sounded the area, and as he went, he set out buoys to replace those so recently removed by the Danes.

Then began the further preparations for battle. A young midshipman named Millard recalled the early-morning scene: “The hammocks were piped up at six, but having had the middle watch, I indulged myself with another nap, from which I was roused by the drum beating to quarters. I bustled on deck, examined the guns under my direction, saw them provided with handspikes, spare breechings, tackles, etc, and reported accordingly.”

Millard heard about the longboat’s mission during the night. “As the gunner’s cabin where I usually messed was all cleared away, I went into the starboard cockpit berth, where I found one of the pilots that had been sounding the night before. He told us that they had pulled so near the enemy as to hear the sentinels conversing, but returned without being discovered.”

And now there would be breakfast aboard the fighting ship. “Our repast, it may fairly be supposed under the circumstances, was a slight one. When we left the berth, we had to pass all the dreadful preparations of the surgeons. One table was covered with instruments of all shapes and sizes, another of more than usual strength was placed in the center of the cockpit. As I had never seen this produced before, I could not help asking the use of it, and received the answer, ‘that it was to cut off legs and wings upon.’ One of the surgeon’s men was spreading yards and yards of bandages about six inches wide.”

Nelson had been up all night dictating orders and having personal meetings with his captains. Each ship had an assigned task and a position to fill. The line would sail north up the King’s Channel abreast of the Danish line and anchor in station, there to slug it out at fairly close range. Nelson had decided to have the line move on the unengaged side of each of the British ships as they took up their assigned berths, and thus afford some protection to his vessels that were to run the entire gauntlet of the Danish line.

At first light, Nelson was convinced of divine intervention when it was found that the wind had veered 180 degrees during the night and now stood fair for his purpose. When the wind freshened around 9:30 am, the signal to weigh and proceed was put out. The men in his fleet said of Nelson, “He never trifled with a fair wind.”

Captain George Murray’s Edgar was first in line. She anchored by the stern in her assigned berth with guns blazing. Next came Thomas Bertie’s Ardent and then William Bligh’s Glatton, each following directions precisely. (This was the same Captain Bligh who was involved in the mutiny aboard Bounty 12 years earlier.) Captain James Walker’s Isis was next. And then the trouble started. Captain Robert Fancourt’s Agamemnon failed to weather the tip of the Middle Shoal and was forced to anchor to avoid grounding. He spent the entire day trying to warp to windward against the current, but that was an almost-impossible task.

Nelson immediately changed assignment: Isis and Captain John Lawford’s Polyphemus would fill the gap, but he was now one ship short. Next to proceed in line was Bellona under Captain Thomas Thompson, but as he passed Isis, he kept too far to starboard and ran aground. Just barely in range, he would be of little help. Nelson himself ordered his flag captain, Thomas Foley, to fill the gap left by Thompson’s Bellona with his flagship Elephant, and she anchored opposite the Danish flagship Dannebrog, a three-decker. Then James Fremantle in Ganges took station ahead of Elephant, followed by Captain James Mosse in Monarch and Captain Richard Retalick in Defiance. Last in line was Russell, under Captain William Cumming, who became confused by heavy smoke, lost sight of his lead ship, and ran aground just astern of Bellona.

Nelson was now three ships short, and the battle had only just begun. His shortened line was by now engaged in a very stiff action with the Danes, and as he paced the deck among the gunsmoke and splinter clouds, he remarked to Colonel C. Stewart of the Marine detachment, “It is warm work, and this day may well be the last for many of us, but mark you, I would not be elsewhere for thousands.”

Captain Edward Riou had charge of five frigates—Alcmene, Arrow, Amazon, Dart, and Blanche—and took up position at the head of the line, where he took the Trekroner battery under fire. This would have been a hard task for ships of the line, and it was an almost impossible one for frigates.

Nelson had counted on subduing the southern end of the line first, so that those engaged there could slip their cables and move to the northern end, where they could help reduce the Trekroner. He had a force of 600 Marines to land and take the fortress as soon as its guns were silenced. But noon came, and then 1 o’clock, as the withering fire continued on both sides, and no Dane had yet struck.

One reason was the constant shuttle from shore by Danish boats bringing replacements to the guns for their comrades who had fallen. Townsmen who had never even been aboard a warship before came on as they were needed and kept the guns going. The carnage on both sides was appalling. Midshipman Millard in Monarch, the most heavily damaged ship in the British line, wrote later that after coming on deck on an errand, he found “not a single man standing the whole way from the mainmast forward, a district containing eight guns to a side, some of which were run out ready for firing, others lay dismounted, and yet others remained as they were after recoiling. I hastened down the fore ladder and felt really relieved to find somebody alive.”

Admiral Thomas Graves in Defiance later wrote, “ I am told that the Nile was nothing to this. I am happy that my flag was not a month hoisted before I got into action—and into the hottest one that has happened the whole of the war.”

The slow-moving Admiral Parker in London, who with his heavier ships was holding the northern approach, became nervous and agitated. He thought Nelson might be in trouble. In his glass he could see the Agememnon, Bellona, and Russell were not in action and were flying distress signals. He could detect no slackening of fire from the Danes, and several of the British line had rigging down. At around 1:30 pm, against the advice of his staff, he put out the signal: “Discontinue the engagement.”

It appears that Nelson had half-expected such an action from his commander-in-chief, for he had instructed his signal lieutenant to keep his eyes on the Danish flagship and inform him the moment she struck. After a few minutes, everyone on the Elephant’s quarterdeck was aware of the signal being flown by Parker. Colonel Stewart of the Marine Detachment later recalled that Nelson continued his walk and did not appear to take notice of the signal. “The Lieutenant meeting His Lordship at the next turn, asked if he should repeat it. [To repeat a signal means ‘I see, I understand, and will obey.’] Lord Nelson answered, ‘No, acknowledge it.’ On the officer returning to the poop, Lord Nelson called after him, ‘Is number sixteen [the signal for close action] still hoist?’ The Lieutenant answering in the affirmative, Lord Nelson said, ‘Mind you keep it so!’”

Nelson continued to walk the deck, “considerably agitated which was always known by him moving the stump of his right arm.” Stewart related the rest of the historic conversation: “After a turn or two he said to me: ‘Do you know what is shown on board of the Commander-in-Chief?’—Number 39!’ On asking what that meant, he answered, ‘Why, to leave off action!’

“‘Leave off action!’ he repeated and added with a shrug. ‘Now damn me if I do.’ He then observed, I believe to Captain Foley, ‘You know, Foley, I have only one eye. I have a right to be blind sometimes.’ And then with an archness peculiar to his character, putting the glass to his blind eye he exclaimed, ‘I really do not see the signal.’”

British accuracy and rate of fire finally began to tell around 2 o’clock as three of the Danish line cut their cables and beached in a sinking condition. Two more made good their escape along the Amager Shoal when they could no longer be fought, and the Danish flagship caught fire. This forced the Danish commander-in-chief, Admiral Johann Fischer, to quit the ship and shift his broad pennant. One after another, the others in the Danish line struck or stopped firing so that, by 2:30 pm, nearly all resistance had stopped.

As the British longboats approached to take possession of the prizes and remove prisoners, shore batteries fired on them through ignorance or confusion. Nelson ordered the boats recalled and fire resumed while he prepared a note to be sent onshore under a flag of truce. It was addressed, “To the brothers of the Englishmen—The Danes.” It read: “Vice Admiral Lord Nelson has been commanded to spare Denmark when she no longer resists. The line of defence which covered her shores has struck to the British flag, but if firing is continued on the part of Denmark, he must set fire to the prizes, without having the power of saving the men who have so nobly defended them. The brave Danes are the brothers, and should never be the enemies of the English.”

Nelson was careful to use deliberate language and to have the message copied by his purser. He then had it sealed with his own arms so that no sign of haste would be apparent. About an hour later a Danish envoy approached under a flag of truce and boarded the flagship Elephant to meet with the victorious and resolute Nelson. By now all firing had ceased, even from Trekroner battery, after nearly four hours of hotly contested action.

The reply from the Danish Prince Royal Frederick asked for clarification of the terms of the cease-fire, and Nelson replied, “Lord Nelson’s object in sending the flag of truce was humanity; he therefor consents that hostilities shall cease, and that the wounded Danes may be taken on shore. And Lord Nelson will take his prisoners out of the vessels and burn or carry off his prizes as he shall think fit.”

Captain Fremantle of Ganges was ordered aboard Elephant while Nelson and the envoy went to confirm the truce with Admiral Parker as British commander-in-chief aboard London. The next day, Fremantle wrote that the truce “produced a cessation to the very severe battle which was certainly as convenient for us as the enemy, as we had several ships on shore and most of the ships crippled so completely that it was with difficulty they could sail out.”

Although the British line was badly damaged, the Danish line was all but annihilated. The prize crews found that only one of the remaining ships in the Danish line was worthy of salvage—the 60-gun Holsteen. Eleven had to be burned, two had escaped when they could no longer be fought, and three had sunk while attempting escape. Dannnebrog was still afire at the end of action, and at about 3:30 pm, she blew up when the flames reached her magazines.

The Danes suffered 794 killed and nearly 900 wounded. More than 2,000 became prisoners of war. The British suffered 256 killed and 686 wounded. Only Monarch of the British line was judged too badly damaged for field repair—she was jury-rigged and dispatched to England. Horatio Nelson’s victory could hardly have been more complete.

Nelson set his crews to work moving out of range of the remaining shore batteries and making repairs, because a formal armistice had yet to be worked out. Parker left these negotiations entirely in Nelson’s hands, just as he had left the fighting to his subordinate. As the talks dragged on for several days, Nelson became convinced that the Prince Royal was stalling because of fear of retribution from the Czar. The British squadron was by now ready for sea, and Nelson was anxious to proceed to Reval, where he hoped to catch at least part of the Russian fleet still fast in the ice.

On April 9, Nelson had decided to ask Parker’s permission to bombard the dockyard and perhaps even the city itself in order to force an agreement from the Prince. But just then word was received from St. Petersburg that Czar Paul had been murdered by his staff officers. His son, Alexander, was now Czar and he had made known his intention to revoke the Armed Neutrality Pact, in effect to side with Britain against Napoleon. The whole question was now moot.

When the Admiralty learned the full details of the action, they ordered the relief, recall, and retirement of Admiral Sir Hyde Parker, and left Admiral Nelson in command of the Baltic squadron.

The assassination of Czar Paul had taken place on March 24, nine days before the battle. Had better communication been available, it is more than likely that the Battle of Copenhagen would not have been fought at all.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments