By Sam McGowan

Of all the better-known Allied aircraft of World War II, the most controversial was Martin’s B-26 Marauder, a twin-engine cigar-shaped medium bomber that was loved by some and hated by many. Among those who hated the airplane were the crews of the Air Transport Command’s Ferrying Division who picked the Marauders up at the factory and delivered them to combat units. Those who loved it included Lt. Gen. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, who used a B-26 as his personal airplane, and most of the pilots and crew members who flew the airplane in combat. On three different occasions, efforts were made to cancel future B-26 production, but in each case proponents of the airplane managed to prevail, thanks in no small measure to the efforts of a diminutive former airshow pilot from Lynchburg, Va., named Vincent “Squeek” Burnett.

After gaining a terrible reputation due to the loss of dozens of crewmembers in training accidents, the Martin B-26 finished the war with the lowest combat loss ratio of any of the American bombers.

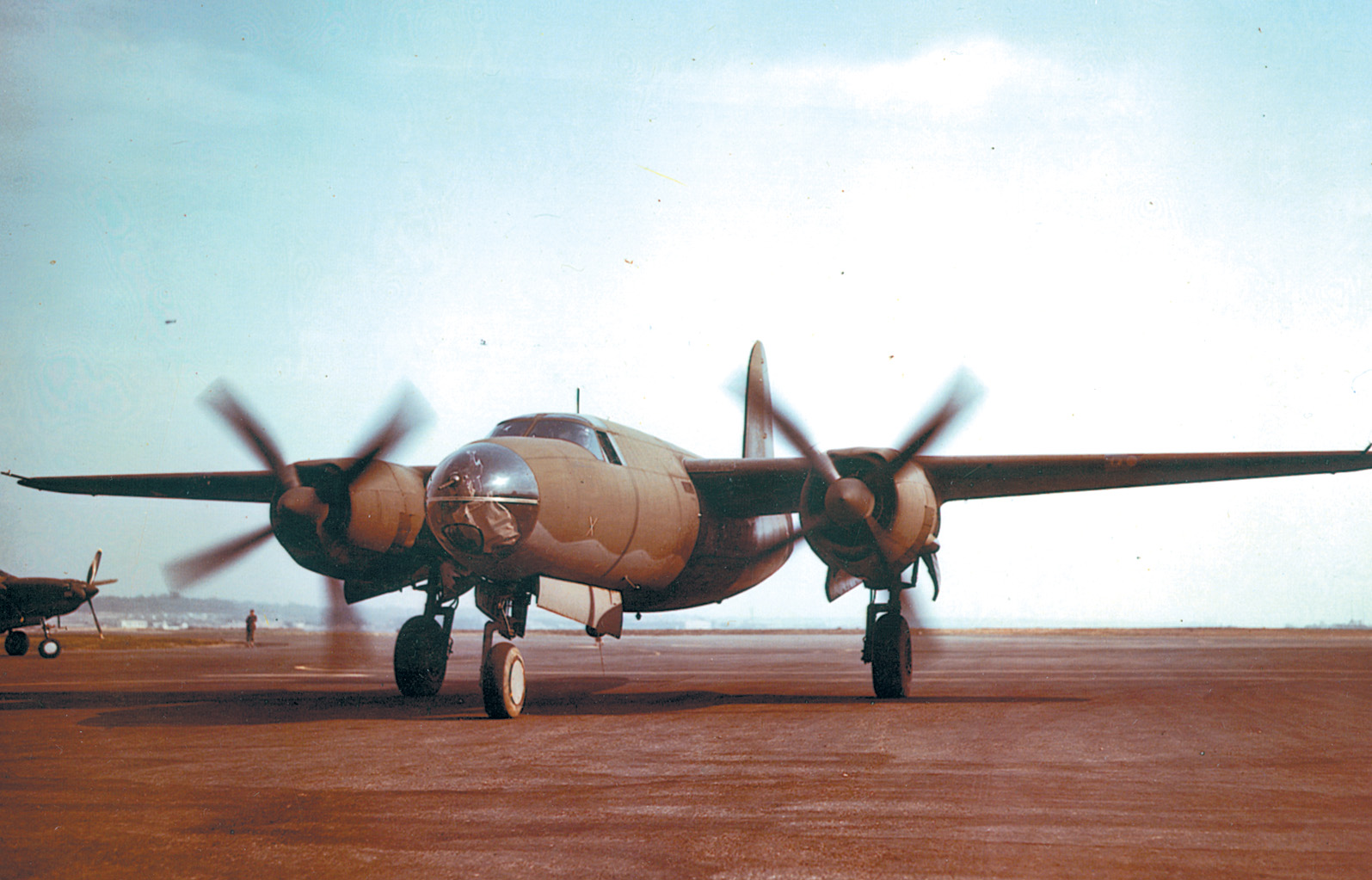

The B-26 came about as a result of an Army Air Corps requirement set forth in January 1939 for a twin-engine, high-speed medium bomber. The Glenn L. Martin Company submitted a design that had been drafted by Peyton Magruder, a young aeronautical engineer who had come to the Martin Company by way of the U.S. Naval Academy and the University of Alabama.

Only 26 years old when he drafted the design, Magruder was well ahead of his time when he designed an airplane that would utilize a high wing loading to reduce drag and allow higher cruise speeds. Of four designs submitted, Martin’s received the highest score from the Army and was awarded the contract. The concept did not come without a price. The thinner wing required much faster than normal takeoff and landing speeds. It also had a consequently high “minimum control speed,” the speed at which a multiengine airplane can lose the “critical” engine without becoming uncontrollable. The advanced design would be largely responsible for the problems that plagued the airplane after it entered service.

It took nearly two years from the date of the Army specification for the first B-26 to take flight, but orders for production aircraft had already been awarded. An accelerated production program spawned enough of the twin-engine bombers to equip one full group by December 1, 1941. The 22nd Bombardment Group (Medium) had received its full complement of airplanes and had enough trained crews that it became the first U.S. Army bombardment group to deploy to its assigned combat zone more or less under its own power after the Pearl Harbor attacks.

The group’s airplanes were shipped to Hickam Field, Hi., by ship, then were reassembled and flown across the South Pacific Route to Brisbane, Australia, where they began arriving in mid-March. After their arrival in Australia, the 22nd moved to the northern coastal hamlet of Townsville and began combat operations against the Japanese in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

A second group, the 38th Bombardment Group, was also partially equipped with B-26s. Two of its squadrons flew the Marauder while two others flew North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers. The 38th was slated to move to Australia, and while the ground units made the move, the aircrews remained in the United States for training. The group’s two B-26 squadrons, the 69th and 70th, got to Hawaii, but never made it to the Pacific Theater.

When the 22nd began operations from Townsville, they followed the same pattern used by the B-25 and Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress-equipped bomber squadrons in the theater. They loaded up with ammunition and bombs at Townsville then flew north to Port Moresby in New Guinea. There the crews were briefed for their missions while the airplanes were refueled. They were then sent out to attack the Japanese. After a raid, they returned to Moresby where they rested before returning to Townsville. Living conditions at Moresby, which was a forward airfield in the summer of 1942, were primitive. The crews slept under the wings of their airplanes in mosquito netting they had brought with them.

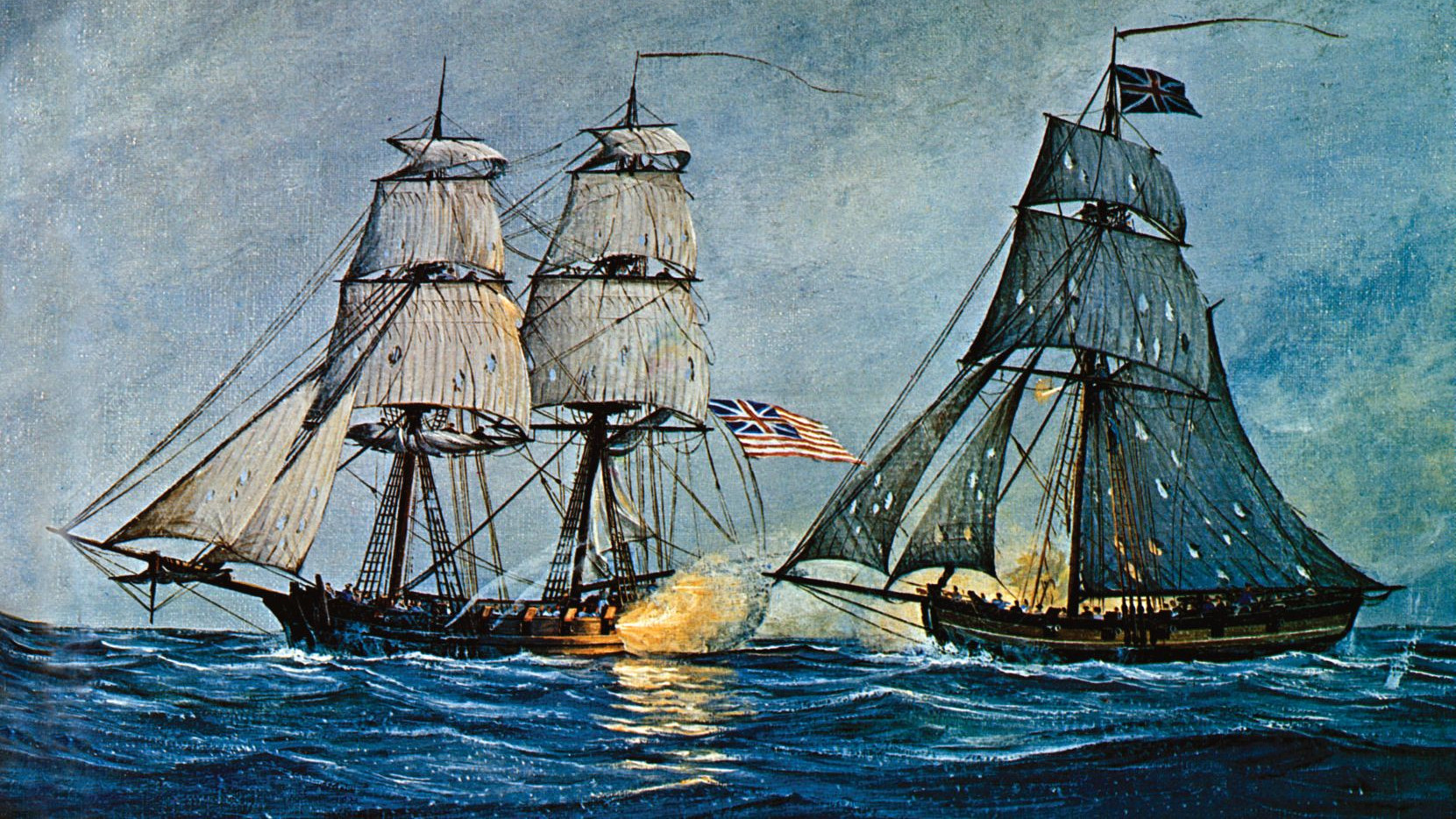

For all of the bomber crews operating in the Southwest Pacific at the time, regardless of the aircraft they flew, missions were small-scale, often with only three airplanes and never more than a dozen in a formation. The bombers often flew unescorted as the few Allied fighters in the theater at the time were needed to defend the forward bases from attacks by the Japanese. The B-26s were sometimes loaded with torpedoes for attacks on ships. On occasion, Marauder crews joined B-17, B-25, and Douglas A-20 Havoc crews in “skip-bombing” Japanese ships at wave-top altitudes.

The high speed of the B-26—it had a top speed of 315 miles per hour—gave the Marauder an advantage lacked by the much slower B-17s. The B-26 featured a dorsal turret, waist and tail guns, and additional guns in the nose. Fixed forward-firing guns were added in pods on the sides of the fuselage. The B-26 crews of the 22nd also used the low-level attack tactics that came to prevail in the Fifth Air Force to which they were assigned, tactics that made the airplanes impossible to attack from below. In more than a year of combat, the 22nd only lost 14 airplanes to enemy fighters, while group gunners put in claims for 94 Japanese aircraft.

Remarkably, few aerial gunners in the Army Air Corps had any formal gunnery training in the early months of the war. Pilots picked gunners from among the ground crews and had them placed on flying status. One of the gunners in the 22nd was John Foley, a young man who had shipped out to Australia as a private with no technical training. When Foley got to Townsville, he began working as an armorer, cleaning the guns and loading ammunition and bombs on a group airplane. Foley impressed the pilot, who chose the young man to fly on his crew as a gunner.

Even though he had no gunnery training, Foley proved to be a natural and his score of enemy planes began to rise. He acquired the nickname “Johnny Zero” and inspired a popular song by that name.

Although they were destined for Australia, the two B-26 squadrons of the 38th Bombardment Group never made it there. Two 69th Bombardment Squadron Marauders and two 22nd Group airplanes that had remained in Hawaii were sent to Midway when Navy codebreakers learned of the Japanese plans to invade the island. The four B-26s had been modified to carry torpedoes. Along with a small force of Navy torpedo bombers, the Marauders were launched from Midway to attack the Japanese fleet. Two of the B-26s were shot down and the torpedoes dropped by the other two were ineffective. The 69th and 70th Squadrons were detached from the 38th Group, which was equipped with B-25s, and were sent to the South Pacific where they operated from Fiji.

Two squadrons of B-26s were active for a time at the top of the world in the 28th Composite Group, a multifunctional combat group that provided the muscle for the Eleventh Air Force in Alaska. The 77th Bombardment Squadron deployed to Alaska from Sacramento, Calif., in January 1942, as part of an Army Air Corps effort to beef up aerial defenses in that desolate region.

The 73rd Bombardment Squadron had been in Alaska for nearly a year, flying obsolete Douglas B-18s. In March 1942, the 73rd turned in its B-18s as they were replaced with brand new B-26s. A third B-26 squadron, the 406th, also moved to Alaska. For a few months the three squadrons flew search and attack missions along the Aleutians chain and, like their peers in the Southwest Pacific, often carried torpedoes. But their stint with B-26s was brief. In September 1942, the Army started replacing the B-26s in Alaska with B-25s.

Even though the B-26s were holding their own against the Japanese, their days in the Pacific were numbered. While the Southwest Pacific air forces commander, Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, was impressed by the Marauder, it was not the medium bomber he wanted in his theater. Fifth Air Force A-20 and B-25 squadrons had mastered the art of low-level attack, and dozens of the light and medium bombers had been modified to become powerful gunships. Kenney believed his command should be limited to one type each of fighter, light bomber, medium bomber, heavy bomber, and transport. His preferences were for the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter, the A-20, B-25, and Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers, and the Douglas C-47 transport.

The B-26s were left out in the cold. B-25s replaced the B-26s in the 22nd Group and the decision was then made to turn the group into a heavy bomber outfit and equip it with B-24s. A few B-26s continued to fly missions with the 22nd until early 1944, but they eventually completely disappeared from the theater. The two former 38th Group squadrons in the South Pacific also transitioned to B-25s.

Even though the B-26s in the Pacific were holding their own in combat, the airplane was gaining a bad reputation at the training bases back in the United States. It started among the ferry pilots who picked the airplanes up at the factories and delivered them to the bases. The problem was that the high wing loading of the first versions of the B-26 made it a “hot” airplane, and it became uncontrollable if a pilot failed to maintain adequate airspeed after an engine loss.

Engine losses on B-26s were frequent. The Pratt and Whitney R2800 engines were prone to failure. When an engine failed, the pilot had to maintain a fairly high airspeed or the airplane would roll upside down and go into the ground. After several ferry crews lost their lives in B-26 accidents, many refused to fly the airplane. An increase in the span of the wing on later models enhanced the Marauder’s performance.

Enter Squeek Burnett. After joining the Ferrying Service right after Pearl Harbor, the veteran air show pilot was assigned to ferry B-26s, among other types of aircraft. Unlike many of the other pilots, Burnett saw no problems with the airplane. When he heard that there was pressure on the Army to cancel the B-26 contract due to the rising accident rate, he began conducting experiments with the airplane on his own. He shut down engines, made low passes with one engine shut down, and turned into the dead engine. Then he began showing the other ferry pilots that the B-26 could be flown safely as long as the pilot had the proper training and maintained sufficient airspeed to keep the airplane from going out of control.

Among the young Army pilots who were to take the B-26 into combat, the bad reputation of the B-26 was increasing. Accident after accident occurred among the crews who were in training, so many that a special committee known as the Truman Committee was appointed to look at the problem. There were several reasons for the accidents. Few of the trainees—or many of their instructors—had acquired any multiengine experience before they were assigned to the Marauder. Furthermore, the Army had made a number of modifications to the production airplanes to prepare them for combat. The basic weight of the airplane had increased and the center of gravity had moved rearward, thus rendering the airplane unstable.

While these were problems that an experienced pilot could handle, the pilots who were filling the ranks of the combat squadrons were severely lacking. Because of the accident rate, the Truman Committee recommended that the B-26s be removed from service. Martin turned to the men who had flown the airplane in combat in the Southwest Pacific for help. The combat pilots took up the cause and saved the airplane from extinction.

After his return to the United States from the raid on Tokyo, former racing pilot Jimmy Doolittle was awarded the Medal of Honor and promoted to brigadier general. He was recommended to General Douglas MacArthur for the position of Chief of Staff for Air in the Southwest Pacific, but MacArthur turned thumbs down on Doolittle and instead chose George Kenney. Doolittle was then chosen to command the Twelfth Air Force in North Africa. Doolittle’s Twelfth Air Force was to include several groups equipped with B-26s. He even ordered one for his personal airplane.

Doolittle had flown the airplane before the war and had considered using B-26s on the Tokyo Raid, but he decided against it because of the airplane’s longer wing span, which afforded little margin of safety on the narrow deck of a carrier. General Henry H. Arnold ordered Doolittle to look into the problems with the B-26s. Doolittle knew of Squeek Burnett’s work with the B-26 and had him transferred to his staff.

Due to the many crashes, the B-26 had been given a number of derogatory nicknames. Among them were “Widow Maker,” “Flying Prostitute,” and “Baltimore Whore.” The many crashes at McDill Field, Fla., led to the ditty “One a Day in Tampa Bay.” The accident rate was just as bad at other B-26 training bases. To show the pilots that the B-26 could be flown, Doolittle went around to the bases to demonstrate the airplanes. Many of those who saw the demos thought they were flown by Doolittle. In reality, the pilot who was putting the airplane through its paces was Captain Vincent “Squeek” Burnett.

In November 1942, the first of three Twelfth Air Force B-26 groups, the 319th Bombardment Group, began operations in North Africa. A new form of warfare had begun for the B-26 crews. While the 22nd Bomb Group crews in the Pacific had functioned primarily within a strategic plan based on the use of air power to weaken and cut off Japanese forces, the Twelfth Air Force B-26s functioned more in the tactical role, supporting ground forces.

The 319th Group was soon joined in Africa by the 320th and 17th Bombardment Groups. The 17th was one of the first medium bomber groups in the Army, and it made an unusual transition. While most of the B-26 groups started out with Marauders then transitioned into B-25s, the 17th had been one of the first

B-25 groups. It had lost its airplanes and crews to Doolittle’s Tokyo mission and was re-equipped with B-26s in mid-1942. Experienced personnel from the 17th formed the initial cadre for the other B-26 groups, including the 319th and 320th.

During their initial operations in North Africa, the B-26 groups functioned essentially the same way as their predecessors had in the Pacific, conducting bombing and strafing attacks against enemy installations, airfields and shipping at low altitude. After less than two months of operations in North Africa, General Doolittle issued orders restricting the B-26s to medium-level bombing, except for attacks on German and Italian shipping in the Mediterranean. The order essentially changed the

B-26s into a medium-level version of the B-17s that made up the heavy bombing component of the Twelfth Air Force.

Instead of coming in low to strafe enemy positions and drop their bombs with accuracy only possible from low altitude, the B-26 crews began using the shotgun tactics of spreading a carpet of bombs over a wide area in hopes that enough of them would hit the target to knock it out. Under the new tactics, which would spread to the heavy bomber and other medium groups as well, only the lead airplane in every element would be equipped with a Norden bombsight for precision bombing. The other three airplanes would toggle their bombs whenever they saw the bombs fall out of the bomb bay of their leader.

Doolittle took advantage of his perks as a numbered air force commander to set up a personal courier service and put Squeek Burnett in charge of it. Burnett went to England with Doolittle and began the courier flights back to Washington from there, piloting a B-26 on the long over-water flights. The flights continued from North Africa. Doolittle also had a B-26 of his own, and some of the crewmembers had flown with him on the Tokyo Mission. Doolittle occasionally accompanied the B-26 crews on missions in his personal airplane.

In mid-May the last German troops in Tunisia surrendered, and North Africa fell into Allied hands. As the ground war declined in intensity, the B-26s began turning their attention toward German and Italian installations on the north shores of the Mediterranean. The Allies were making plans to invade Sicily, and the mediums joined the heavy bombers in attacking targets that would assist the invasion forces.

In addition to shore installations and airfields, the B-26s also concentrated on coastal shipping along the Italian coast. After Allied forces landed on Sicily, the Marauders assisted ground forces by bombing German strongpoints. From that time on, the role of the B-26 in the Mediterranean was oriented toward making life easier for the advancing ground forces. In mid-September, Allied forces landed at Salerno, moving the war farther north toward Rome and, eventually, toward Germany. However, the German troops in Italy put up a tenacious defense, and the Allied advance slowed; German troops continued to control much of northern Italy until the end of the war.

Mediterranean Air Force B-26s played a major role in one of the most controversial events of World War II. The Allied advance northward up the boot of Italy was stalled at the town of Cassino by a steadfast German defense. Outside the town on top of Monte Cassino sat the ancient Benedictine abbey named for the overlooking mountain.

Some of the senior Allied commanders thought the Germans were using the abbey as an observation post. On February 15, 1944, several formations made up of 142 B-17s and 112 B-25s and B-26s bombed the ancient monastery. The bombing ruined the abbey, and the Germans, who had previously respected the building’s religious significance, moved in and occupied the rubble, turning it into a strongpoint while the battle raged on around the city.

After weeks of failing to capture the town, General Mark Clark, the Allied commander in Italy, decided to flatten it. On the morning of March 15, 1944, a formation of B-25s commenced the attack, which lasted until noon. A force of 275 B-17s and B-24s and some 200

B-25s and B-26s dropped more than 1,000 tons of 1,000-pound bombs on the city. The B-26 crews “stole the show at Cassino,” as more than 90 percent of their bombs fell within the designated target area. The town was reduced to rubble. Even though the Air Corps had done its job, the ground battle continued for several more weeks.

In early 1943, the 322nd Bombardment Group moved to England and became operational as part of the Eighth Air Force. General Ira Eaker, the Eighth Air Force commander, was looking for ways to incorporate the newly arrived B-26s into the strategic bombing offensive. Because of the highly effective low-altitude attacks by light and medium bombers in the Pacific, the air staff encouraged Eaker to use the B-26s in low-level attacks on German targets on the coast of Europe.

But Europe was a different kind of war. For more than two years German forces had occupied France and the Low Countries, and they had built up strong defenses against air attack over nearly three years of fighting. On May 14, the 322nd flew its first mission, a low-level attack by 12 B-26s on a power station at Ijmuiden in Holland.

Beginner’s luck held casualties to a minimum. The Marauders encountered heavy antiaircraft fire over the target, but managed to drop their bombs without loss. One airplane broke off the attack after sustaining several hits from cannon fire, and two suffered major damage over the target. Although two of the damaged airplanes made it to safety in England, the third experienced landing gear problems and the pilot ordered the crew to bail out. He lost his own life when the airplane went into a steep spiral and he was unable to get out.

Three days later, on May 17, the 322nd sent out another formation of 11 airplanes against the same target, which had suffered little damage. This time the attackers were not so lucky. One airplane aborted over the English Channel, but all 10 of the others were lost! Five airplanes were shot down by flak, while two more were destroyed in a mid-air collision. Only four airplanes came off the target. They were intercepted by German fighters, and not a single Marauder escaped the air battle that followed. The inauguration of the B-26 into combat in Western Europe had met with disaster.

After the May 17 debacle, the 322nd was taken off of combat operations while new tactics were developed. Future Marauder missions would only be conducted at high altitudes to keep them out of range of the deadly ground fire from automatic weapons that made low-level attacks so costly. No missions would be scheduled to take the bombers beyond the range of fighter escort. In mid-July the B-26s resumed operations with a raid on Abbeville, but instead of going in at treetop level, the Marauders bombed from medium altitudes above 10,000 feet.

The new tactics worked. Over the next two weeks, the B-26s flew 11 more missions and only lost two airplanes. The Eighth Air Force leadership had hoped that the introduction of the medium bomber to the strategic bombing campaign would cause the Germans to move fighters into France and take pressure off the heavy bombers. The Germans, however, continued to concentrate their fighters on the B-17 formations and more or less ignored the B-26s (at this point in the war, all of the Eighth Air Force B-24s had been deployed to Africa). Now the main danger to the Marauders was flak.

After the disaster at Ijmuiden, the B-26s were used solely as medium-range bombers, concentrating their efforts on airfields in France and the occupied countries. In essence, the attacks were wasted. Most of the German fighters had been pulled back into Germany to defend the Nazi homeland or had been sent to the Eastern Front. Eaker’s hope that the B-26 formations would draw fighters off the heavy bombers never materialized. Damage to the German airfields could be quickly repaired, so the attacks were only effective in that they kept the fields from being used while they were under attack.

The Eighth Air Force also came up with a plan to send B-26s along with the B-17s as escorts. Experiments with the YB-40 conversion of B-17s into heavily armed escort gunships had been unsatisfactory. The B-26 plan was equally futile. The airplane was too fast for the B-17s and lacked sufficient range to accompany the heavy bombers into those areas where they were most likely to be attacked. Furthermore, in spite of their speed, the B-26s were as vulnerable to fighter attack as the B-17s.

By the end of August, the 322nd had been joined by three more B-26 groups: the 323rd, 386th, and 387th. All four groups were part of the Eighth Bomber Command, but a reorganization was under way. At the Casablanca Conference in early 1943, the Allies had developed plans for the Combined Bomber Offensive, a sustained strategic bombing effort against German and Italian targets.

When Allied airmen began operations on the African continent, the Ninth Air Force had been organized to control operations from Palestine. For more than a year, Ninth Air Force heavy bombers operated against German and Italian targets along the Mediterranean, including the famous low-level attack on the Ploesti oil fields. In October 1943, the Ninth Air Force was broken up and the group headquarters and the numerical designation moved to England where they were given to the new tactical air force that was being organized to support the Normandy invasion.

The heavy bombers that had been in the Ninth and Twelfth Air Forces were to transfer to the new Fifteenth Air Force, which would operate from Italian bases as part of a massive heavy bomber campaign against Germany.

In England, the headquarters of the Eighth Air Force was elevated to become the United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe which would control a new Eighth Air Force made up of what had been the VIII Bomber Command and the new Fifteenth Air Force. Doolittle went to England to take control of the new Eighth. The medium bomber groups that had been part of the Eighth transferred to the new Ninth Air Force along with the light bomber groups that flew A-20s and certain fighter groups that had been designated for the ground attack role. Twelfth Air Force would also become a tactical air force to support ground operations in the Mediterranean.

When the Ninth Air Force headquarters relocated to England in the fall of 1943, the IX Bomber Command received the 3rd Bomb Wing, consisting of four B-26 groups from the Ninth Air Force. The 3rd Wing commander, Colonel Samuel E. Anderson, assumed command of the IX Bomber Command, changing the unit’s mission from heavy to medium bomber operations. The B-26s of the 322nd, 323rd, 386th, and 387th bombardment groups would be joined by four other B-26 groups and three light bomber groups flying A-20s. Several groups of P-47 and P-51 fighter-bombers made up the remainder of the striking power of the Ninth, while the IX Troop Carrier Command supported the Allied airborne forces.

Ninth Air Force B-26s played a minor role in Operation Crossbow, an Allied air effort against suspected German V-weapon launch sites on the coast of France. In the spring of 1943, a Royal Air Force photo-interpreter had detected the first evidence of German missiles, though it would be nearly a year and a half before the first of the V-bombs exploded on English soil.

In December 1943, the Allies commenced Crossbow, a bombing campaign aimed at disrupting the German plans to implement their new weapons. The vast majority of the effort was carried out by Eighth Air Force heavy bombers, but the Ninth Air Force B-26 groups were credited with 26 “Category A Damage” air strikes against V-1 launch sites by May 1944, when the attacks came to an end.

During the last week of April 1944, the IX Bomber Command received its assignments for the upcoming Normandy invasion. During the weeks preceding the invasion, the Ninth Air Force B-26 and A-20 crews were to train for the invasion while conducting pre-invasion attacks against railroad marshaling yards, airfields, and coastal batteries and continuing attacks against the robot-bomb targets when possible.

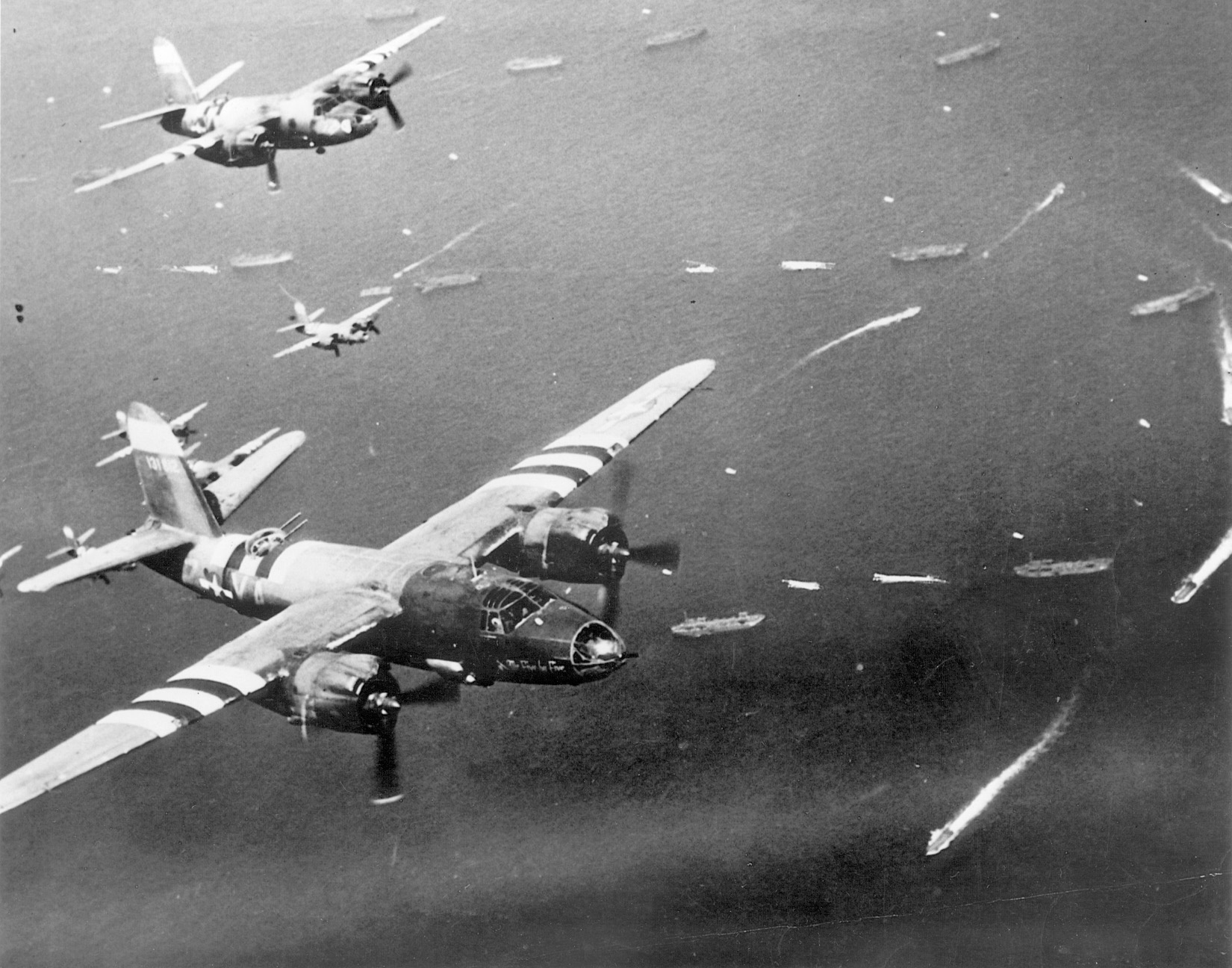

As the preparatory invasion phase continued, the A-20s and B-26s focused their attention on all airfields within 130 miles of the strategically important French village of Caen, along with selected radar stations, with the objective of neutralizing them. The D-day plan called for all 11 groups to attack six German heavy artillery batteries—positioned in the English Channel—that were in range of the invasion fleet, Five minutes before the landings, the B-26s were to bomb seven heavily defended positions inland from Utah Beach.

Prior to the invasion, the B-26s worked in close coordination with IX Fighter Command fighter-bombers. One mission against railroad yards at Hasselt, Belgium, involved 163 B-26s, which dropped 263 tons of bombs from medium altitudes, and 101 dive-bombing P-47s that delivered 120 250-pound bombs. The damage to the target was severe.

The attacks on marshaling yards usually involved four or five groups of 34 airplanes each, all bombing a single rail center. The shotgun tactics that had been developed in the Twelfth Air Force were discontinued. Ninth Air Force commander General Lewis Brereton had the B-26s break up into small sections of four to six airplanes, thus concentrating their bombs into a smaller area and reducing the danger to civilians. Other missions focused on road and railroad bridges, especially after May 24 when restrictions against attacks on the bridges over the Seine River were lifted.

Prior to the invasion, all tactical aircraft, including B-26s, were painted with invasion markings, special patterns of alternating white and black stripes on the wings and fuselage that were designed to make the airplanes easily recognizable to the ground forces. The invasion plans called for the medium bombers to remain at medium altitudes, but after the invasion was postponed for 24-hours, the weather on June 6, 1944, saw a 3,000-foot overcast above the beaches.

Since the B-17s and B-24s were equipped for blind bombing through clouds, consideration was given to canceling the medium mission and diverting the heavies from their planned targets at Caen. General Anderson obtained approval for his medium bombers to drop below the overcast to complete their missions.

While every effort had been focused on the invasion itself, the D-day landings were just the beginning for all of the tactical aircraft assigned to the Ninth Air Force. Once troops were ashore, they had to stay there to be effective, and tactical air power was aimed toward providing every possible form of assistance. The

B-26s were assigned to attack gun batteries and other strongholds so that the Allied forces could break out of the beachhead and advance inland.

In early August the breakout finally materialized, and as the ground forces advanced into France they began capturing Luftwaffe airfields. As airfields were overrun, Ninth Air Force fighter-bomber groups began moving across the English Channel and onto the captured fields. The Army had established a policy that tactical aircraft would operate from airfields as close to the battle lines as possible, and by the second week of August the last of the fighter-bombers were operating from French bases. By the end of the month, four B-26 groups were also operating from fields in France.

While the troops on the Normandy beachhead were working to effect a breakout, Twelfth Air Force B-26s were engaged in softening-up operations in preparation for the invasion of Southern France, scheduled for August 15. Enemy airfields in the Po River Valley were assigned to the B-26s. Just before the invasion, the B-26s were sent to attack submarine pens at Toulon. The Germans elected not to oppose the landings and withdrew northward, away from the beaches.

There was very little resistance from the Luftwaffe, and German ground defenses in Southern France were so weak that the entire region was in Allied hands within a few weeks of the landings. As bases became available, Twelfth Air Force B-26s moved into France to join their peers of the Ninth in supporting the Allied advance into Germany.

Because the B-26s were nearly always escorted and German fighter defenses were concentrated on the defense of Germany itself, the Marauders were rarely subjected to enemy fighter attack. That changed suddenly on December 23 during the Battle of the Bulge, when a large force of German fighters struck

B-26s engaged in attacks on bridges and communications centers. It was the worst day in Marauder history as 35 B-26s were shot down and 182 others suffered battle damage ranging from light to severe.

Initial reports indicated that more than 200 Marauders were missing, though most were later accounted for. The B-26 crews had gotten a taste of the kind of combat the heavy bomber crews had endured for more than two years. The heaviest losses were sustained by the 391st Bomb Group, which lost 16 planes in the morning attack, but still managed to mount a second attack in the afternoon. The group failed to link up with its assigned escort, and the German fighters took advantage of the opportunity. For the day’s activities, the 391st received a Presidential Unit Citation. Unfortunately, one flight of B-26s mistakenly bombed a railroad marshaling yard that was in Allied hands and filled with tank cars loaded with precious gasoline destined for the U.S. Third Army.

Fortunately for the B-26 crews, the heavy losses suffered on December 23 represented a dying effort by the Luftwaffe. Even though the Germans had deployed destructive new weapons, including Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighters, the advancing Soviets had captured the oil fields in the Balkans that had provided the bulk of Germany’s crude oil and Allied bombers had severely crippled the synthetic oil industry.

The Germans had the fighters, but their numbers were not sufficient to change the inevitable outcome. They also lacked fuel, and the Luftwaffe fighter command was suffering dreadful losses among its pilots.

Over the following four months the Allies advanced farther into Germany and the mission of the B-26 was accomplished.

Sam McGowan is a frequent contributor. He resides in Missouri City, Texas, and is the author of The Cave, a novel about the Vietnam War.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments