By Arnold Blumberg

As the badly routed Union army raced in confusion for the safety of Washington, D.C., after its defeat at the First Battle of Manassas on July 21, 1861, Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell ordered his chief of artillery, Major William F. Barry, to post as much artillery as he could gather on the heights near Centreville as a deterrent to any Confederate pursuit. The major scraped together 20 cannons from five separate artillery batteries and placed them as directed. By doing so, he created the war’s first artillery reserve, a tactical formation of massed cannons designed to provide concentrated and sustained firepower in support of infantry and cavalry forces. It would not be the last.

Soon after First Manassas, the Lincoln administration tapped Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan to be commander-in-chief of the Union Army. McClellan, who modeled himself after French leader Napoleon Bonaparte, agreed with Napoleon’s maxims that war should be fought primarily with artillery and that “the better the infantry, the more one must husband and support it with good [artillery] batteries.” Before he initiated a decisive attack, Napoleon always used his reserve artillery to pulverize the enemy with an intense bombardment. By the end of 1861, McClellan had come around to the same view, seeing the war as “a duel of artillery” and refusing to move, said one critic, until he had 600 guns on hand to support him. Like Napoleon, “Little Mac” considered big batteries and massed firepower the secret to victory on the battlefield.

The Artillery Reserve

When organizing the Artillery Reserve for the Army of the Potomac, McClellan did not have to rely on the Napoleonic model alone. General George Washington in 1776 had carefully apportioned his artillery assets, attaching two guns to each infantry brigade with the remaining pieces stationed near army headquarters under the eye of a colonel, who oversaw the employment of the army’s artillery branch. During the Revolutionary War, Washington maintained the bulk of his cannons in the Army’s reserve artillery pool. The reserve was not expected to contribute to a battle by throwing its considerable weight of shot and shell at the enemy, but instead to act as a supply, maintenance, and replacement source for the artillery already attached to the different infantry formations.

In the War of 1812, inexperienced artillery officers and the lack of assistance from the War Department thwarted efforts to create an effective artillery reserve for the United States Army. During the Mexican War, General Zachary Taylor’s force in northern Mexico was too small to support an artillery reserve. Furthermore, the excellent work done by the light flying batteries, working in small increments, negated the need for reserve artillery in Taylor’s command. General Winfield Scott’s cross-country invasion force contained a number of heavy ordnance pieces, mostly siege guns, which could have properly been designated a reserve. Nevertheless, due to the nature of the terrain in the approach to Mexico City and the small number of guns, Scott decided against grouping the pieces into a formal artillery reserve.

Henry Hunt: Commander of McClellan’s Artillery Reserve

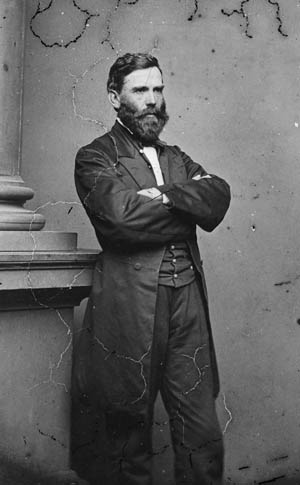

When McClellan began his 1862 campaign, his field army could draw on 92 batteries, including 520 cannons, 11,000 artillery horses, and 12,500 gunners. Of the 299 pieces of ordnance accompanying the Army of the Potomac down to the Virginia Peninsula, 100 of them, with calibers ranging from 3-inch to 20-pounder rifles, were allotted to the artillery reserve numbering 22 companies—eight regular and four volunteer units. The first brigade of horse artillery (four companies strong) was also created, forming part of the reserve. The whole came under the able command of Colonel Henry Hunt.

Hunt, a native of Detroit and the son of a career infantry officer in the U.S. Army, was an 1839 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point. Upon graduation, he was assigned to the artillery branch of the Army. During the Mexican War, Hunt participated in Scott’s campaign, where he was wounded twice and brevetted captain and major. Subsequently, he joined a three-man board along with Colonel William H. French and Major William Barry and helped write the Army’s authoritative manual of artillery use, in which he first propounded his theory of a mobile artillery reserve.

Promoted to the regular rank of major in May 1861, Hunt helped protect the defeated Union army’s left wing at Blackburn’s Ford in the retreat from Manassas. As part of McClellan’s reorganization of the Army of the Potomac, the 42-year-old Hunt was promoted to colonel and chosen to command McClellan’s Artillery Reserve. Hunt had shown at Manassas that he had the abilities of a combat officer as well as an administrator who could handle what was the largest artillery line command in the history of the United States Army up to that time.

A Proactive Artillery Reserve

At the end of July 1861, the artillery reserve was the first complete organization of the Army of the Potomac. It was destined to be the one that lasted through much of the war with the fewest changes. It consisted of 100 guns, including 18 of the 52 batteries with the army. Of these, 14 were regular units and four were volunteer units. Each was equipped with six guns, half 12-pounder smoothbore Napoleon Model 1857 guns and the remainder 3-inch rifles. Three of the volunteer units were armed with 20-pounder Parrots, while the fourth handled six 32-pounder bronze howitzers. The whole was organized into five brigades: one consisting of the four horse artillery batteries and a second of four volunteer batteries, while the other 10 batteries made up three additional brigades. The armament of the reserve was intentionally comprised of different gun types for the purpose of meeting any probable combat contingencies in the field.

As Hunt visualized it, the artillery reserve would be a separate auxiliary from the cannons attached to the main army, but its functions would not be limited to the replacement and reinforcement of frontline batteries. He explained: “It is often desirable to occupy positions with guns for special purposes: to command fords, to cover the throwing and taking up bridges, and for many other purposes for which it would be inconvenient and unadvisable to withdraw their batteries from the troops. Hence it is necessary for reserve artillery.” By 1864, Hunt’s ideas had evolved concerning the needed independence of an artillery reserve. According to Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, an aide to Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, Hunt insisted that “the artillery of an army [i.e., the reserve] be as a corps command, and the batteries detailed to corps commanders, as detached brigades under the corps’ chief of artillery and subject to the like governance with any other like detached brigade.”

As commander of the artillery reserve, Hunt was assisted in its administration by a staff consisting of an adjutant, a quartermaster, an ordnance officer, a chief medical officer, and a commissary. The quartermaster had charge of a 100-wagon train that hauled extra ammunition for the guns. As a mere colonel and staff officer, Hunt was not supposed to have a personal staff. The size of his military family was duly constrained by that fact.

Hunt and his staff had to manage and maintain 18 separate artillery batteries. Each battery had two or three forage wagons, a rations wagon, baggage wagon, battery wagon (holding spare parts and tools), as well as one traveling forge carrying blacksmith tools, horseshoes, nails, spare hardware, and iron. The guns, caissons, limbers, and wagons were pulled by teams of six horses or mules. At full strength, most batteries held six guns crewed by nine men (11 if horse artillery) plus five officers, two staff sergeants, five artificers, two buglers, and one guidon bearer—up to 150 men per battery.

The War Department’s Strict Rank Structure For Artillerists

The rank structure of the artillery branch of the Army of the Potomac presented a chronic dilemma that impeded the reserve artillery from performing to its full potential. During the conflict, the Army’s artillery service never had its required share of field-grade officers (majors, lieutenant colonels and colonels). It was no easy task training men to lead multiple field artillery units whose effective employment on the battlefield demanded sound knowledge of the basic principles of chemistry, physics, geometry, and mathematics. Compounding the problem was the fact that most of the Army’s prewar artillery field-grade officers had no practical experience in the tactical handling of field artillery. These men had spent the years before the Civil War as paper-pushing administrators while much of the active artillery assets were posted in penny packet-sized units at frontier stations, performing duties unrelated to basic artillery service. Furthermore, the Army had never used artillery in massed formations. In the eyes of the War Department, the current bunch of ranking artillery officers was disqualified from field command through lack of practical experience.

In addition to a dislike for field-rank artillerists, the War Department cared little for artillery generals (during the Mexican War the highest ranking artillerist was only a colonel). In 1861, federal law allowed for only one brigadier general per 40 infantry or cavalry companies. Since the basic artillery administrative unit was the battery (referred to more commonly as a company), and the Army of the Potomac under McClellan’s early projections was to contain 60 batteries, under the governing statute the artillery service was entitled to only one general.

This interpretation of the law prevented McClellan from making Hunt a brigadier general since he had already promoted Barry in August 1861. The restriction on the creation of general officers for the artillery would be a sore point throughout the war as deserving officers saw little chance of advancement in rank. Hunt lost two of his most trusted and experienced subordinates as a result of the War Department’s rules. William Hays and George W. Getty, both graduates of the United States Military Academy, had been made lieutenant colonels on McClellan’s staff in 1861, in order to retain their services. In late 1861, they were each given command of one of the artillery reserve’s brigades. In that capacity Getty performed well on the Peninsula and at Antietam, while Hays did equally good service during those campaigns and at Fredericksburg. But by the end of 1862, both had left the reserve to take command of infantry brigades and the general’s star that came with it.

“This Doubled My Labors and Responsibilities”

The laws restricting rank in the artillery service forced Hunt to employ lesser field-grade officers to important commands. Majors Albert Arndt and Edward R. Petherbridge were volunteer soldiers who were assigned brigades in Hunt’s reserve. To fill the top command of his fifth artillery brigade, Hunt had to choose a mere captain, J. Howard Carlisle. Although all three proved their competence in the field, their low rank made it hard for them to exercise control when dealing with officers of higher rank from other branches of the Army. Commenting after the war on the War Department’s bias against promoting artillerists, Hunt declared: “This doubled my labors and responsibilities, it took from me all hope of making the service [the artillery of the Army of the Potomac] what it should be.” Hunt himself was offered a chance to leave the artillery reserve in March 1862, when Irvin McDowell demanded that Hunt be transferred from his post and promoted to brigadier general of volunteer infantry. McClellan denied McDowell’s demand.

A more severe problem facing the artillery reserve was directly related to the junior rank its members held vis-à-vis their infantry and cavalry comrades. During the first years of the war, a number of batteries, normally commanded by an artillery captain, would be assigned to each infantry brigade or division. This practice left the decision as to employing the guns to the division commander, who was usually not well versed in the proper use of cannons. The results were that the infantry division leader would overrule his artillery commander. Consequently, on many occasions cooperation between the separate branches would be impaired, and the guns would not be employed effectively in combat.

A Slow and Steady Fire Doctrine

In the area of artillery doctrine, Hunt’s artillery reserve led the way during the war. Hunt strove to employ his artillery mainly to supplement friendly infantry fire in repulsing enemy attacks by concentrating his artillery firepower and then using that power primarily against the opponent’s foot soldiers. Drawing from a ready mass of fresh batteries held in the artillery reserve allowed for just such support. An important tenet of Hunt’s was the slow and steady firing of his cannons—never more than one round per minute. Any faster rate of fire, Hunt felt, suggested panic on the part of the gunners that might be imparted to the very infantry they were attempting to bolster. “Young man,” Hunt said to one of his cannoneers, “are you aware that every round you fire costs $2.67?” He wanted to make every penny count.

The Reserve Artillery’s Victory at Malvern Hill

The reserve first experienced the rigors of war during the Peninsula Campaign in the summer of 1862. Faced by Confederate fortifications fronting Yorktown, Virginia, McClellan deemed it necessary to conduct a siege to reduce the place. For two weeks the artillery reserve assisted the army’s siege train, commanded by Colonel Robert O. Tyler, using its men and animals to move supplies from Fortress Monroe and furnishing officers to assist army engineers in constructing battery positions.

During the subsequent Seven Day’s Battles (June 25-July 1, 1862), the artillery reserve played a key role. On July 27, at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, six batteries of the reserve, 32 guns under Getty, were rushed to the north side of the Chickahominy River. On arrival they helped the beleaguered Union V Corps, isolated from the rest of the Federal army, during its fighting withdrawal, and were “hotly engaged with the enemies’ batteries.” In the end, nine cannons were lost to the onrushing Confederates. At Glendale, on June 30, guns from the reserve again put in a solid performance in that bitter fight.

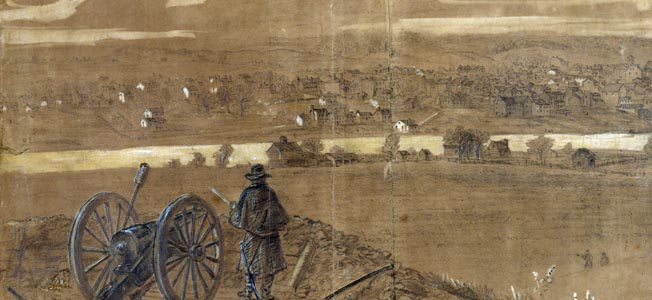

June 30 found McClellan’s army stationed on Malvern Hill. That afternoon, a Confederate column composed of infantry and artillery approached the southwestern flank of the Union position. Thirty-six pieces from the artillery reserve went into action, smashing Confederate soldiers and guns and forcing the intruders to retreat. The following day, July 1, the Army of Northern Virginia threw itself against Malvern Hill proper. Its frontal attack was crushed by a mile-long line of 100 guns topping the hill. Hunt, going against doctrine, had placed the Artillery Reserve in close support of the frontline batteries near the Crew House, as well as a battery of giant 32-pounder howitzers on the right. Farther back, on the crest of the hill, Union siege guns— 4½-inch Rodman rifles, 8-inch howitzers, 30-pounder Parrot guns, and long-rage Whitworth 10-pounders—added their firepower. Under their rectangular headquarters flag, sporting one white star on a red background, the unit’s cannons were positioned during the fight on the western and southern slopes of Malvern Hill, guarding those approaches to the Union position.

That afternoon, the Confederates made a concerted effort to take Malvern Hill, but the weight of Hunt’s artillery stunned them. Against the deadliest cannon fire of the war, the Confederates pushed within pistol range before being driven back. “The battle frequently trembled in the balance,” Hunt wrote. “The last attack was very nearly successful and we won from the fact that we kept our reserves in hand for just such an attack.” At the climax of the battle, Hunt fired his long-range 32-pounder howitzers at close range to devastating effect.

Defeat at Fredericksburg

On September 5, as a reward for his critical role at Malvern Hill, Hunt was elevated to chief of all the artillery of the Army of the Potomac and promoted to brigadier general. Replacing Hunt as commander of the artillery reserve was Lt. Col. Hays. The 43-year-old Hays had graduated from West Point in 1840, fought in the Mexican War, and spent most of the interwar years on routine garrison duty. He inherited a command sorely in need of horses, battery vehicles, cannons, and replacement crews. His force consisted of about 100 cannons.

During the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, the Artillery Reserve, reduced to seven batteries (42 guns) of the army’s total of 62 and manned by 950 personnel, covered the deployment of the Federal army along Antietam Creek. Four of its horse artillery batteries under Captain John C. Tidball provided valuable and steady support in the center of the Union line. Other than that, the artillery reserve proved less effective than expected in the horrific battle.

By the end of the year, the Artillery Reserve comprised nine of the army’s 69 batteries. The unit saw action at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 11. That day it participated in a two-hour cross-river bombardment of the town, followed by eight more hours of firing, to clear a path for engineers to lay pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River in the face of vicious Confederate sniper fire. After heavy and devastating artillery attacks on the city involving over 100 artillery pieces, which ruined many parts of the town but utterly failed to dislodge the dug-in enemy, the reserve remained on Stafford Heights, too far out of range to do any harm to the enemy south of the river and posted behind Fredericksburg. As a result, it played little part in the infantry fight on the 13th.

Even before the fiasco at Fredericksburg, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, commander of the Army of the Potomac, wanted to break up the Artillery Reserve and distribute its assets to the infantry divisions. He reasoned that if a mass of artillery was required for infantry support it could be accomplished by withdrawing the needed batteries from the infantry corps and divisions. That specious argument was disproved at Fredericksburg. When asked to relinquish their artillery even for a short time to blast the enemy from the Rappahannock shore, the infantry commanders strongly demurred before grudgingly relenting.

Hunt Removed From Command in the Chancellorsville Campaign

During the Chancellorsville Campaign (April 29-May 6, 1863), the Artillery Reserve, now comprised of six field batteries and six siege batteries out of 71 batteries in the army, came under the command of Captain William M. Graham. For most of the operation the Artillery Reserve was placed near Falmouth to aid the Union crossing of the Rappahannock River north of Fredericksburg. Its only real contribution to the campaign was long-range fire support at the Battle of Salem Church on May 4, and then covering fire as the Union VI Corps recrossed to the north side of the Rappahannock after the fight.

The relative impotence of the reserve during the Chancellorsville campaign was directly attributed to Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, then commanding the Army of the Potomac. Hooker felt that local commanders should control the operation of the artillery and that centralization at the division or even brigade level was unneeded. After Hunt heatedly argued against that doctrine, Hooker effectively removed Hunt from command. “He showed so much ill feeling,” Hooker later wrote, “that I was unwilling to place my artillery in his charge.” It would prove to be a disastrous mistake. The result was a wide dispersion of the Union Army’s artillery assets that prevented it from countering Confederate attacks. As I Corps artillerist Charles Wainwright noted in his diary, “No one appeared to know anything, and there was a good deal of confusion.” Following the devastating defeat, Hooker quietly restored Hunt to command before being removed himself.

Repulsing Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg

For the Gettysburg Campaign (June 3-July 14, 1863), the Artillery Reserve, was 130 guns strong and made up 22 of the army’s 67 batteries grouped in five brigades. Brig. Gen. Robert O. Tyler commanded. Thirty-two years old at the time, Tyler was a graduate of west Point Class of 1853. During the Peninsula Campaign, he had led the army’s siege train. Leading the individual artillery brigades were one lieutenant colonel and four captains. During the fight of July 2, batteries of the reserve did much to blunt Confederate attacks on the Union left flank at the Wheat Field and further north near Cemetery Ridge.

On July 3, under the supervision of Hunt and Tyler, batteries of the Artillery Reserve, along with other artillery units from unengaged infantry corps, filed onto Cemetery Ridge during the day. By ordering his own gunners to cease fire during the massive Confederate bombardment preceding Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s famous charge, Hunt helped convince Confederate General Robert E. Lee that the Union artillery had been destroyed. It had not, as Hunt’s gunners soon demonstrated, unleashing a whirlwind of fire into the onrushing Confederate ranks and helping to smash Pickett’s valiant but doomed charge. During the battle, the supply train attached to the Artillery Reserve also helped turn the tide, issuing some 70 wagon loads, or 19,000 rounds, of ammunition from its artillery park located just behind the main defensive line of the Army of the Potomac. Like the Confederate infantry attack on the hot afternoon of July 3, the Battle of Gettysburg would be the high-water mark of the war for the Artillery Reserve as well.

Modifying the Artillery Reserve For the Overland Campaign

During the Overland Campaign of 1864, the Artillery Reserve, now under Colonel Henry S. Burton, a West Point classmate of Hunt’s, contained four artillery brigades (24 batteries totaling 62 guns) made up of field artillery, siege guns, and the heavier field pieces of the army. During the Battle of the Wilderness, most of the reserve was not engaged but sent to the rear because, as one cannoneer wrote: “We could do nothing because no horses could have pulled a gun through the brush in which the infantry were fighting.”

During mid-May 1864, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, newly selected commander of the entire U.S. Army, was in the midst of his march through the Virginia wilderness and river country toward Richmond. Grant remarked, “This arm [the Artillery Reserve] was in such abundance that a fourth of it could not be used to advantage in such country.” In other words, the Artillery Reserve was to be disbanded and replaced by high angle firing mortars and howitzers more suitable for the rough terrain and later siege work required at Petersburg. Upon hearing this, Hunt got Grant to modify his order of May 17 to that effect. Only one 20-pounder Parrot battery would be dispensed with; each artillery battery in the army would be reduced from six to four pieces, with the remaining batteries distributed among the infantry corps of the Army of the Potomac. This plan allowed the Artillery Reserve units, although attached to the different infantry formations, to remain intact and available for possible use as a mobile reserve in the future if such was warranted.

The End of the Artillery Reserve

The remainder of the war was an anticlimax for Hunt and the Artillery Reserve. After the war, Hunt reverted to his regular army rank of colonel and served as president of the Army’s peacetime artillery board before becoming governor of the Soldiers’ Home in Washington in 1883. He died at his post six years later.

The fate of the Artillery Reserve was a result of changing battlefield conditions. A throwback to the Napoleonic model, it was a mechanism for the offensive and defensive use of artillery for “special purposes,” as Hunt’s words described it. But the concept was eventually rendered obsolete by the development of the rifled musket and increased reliance on trench warfare. It survived as long as it did because it was able to efficiently act as a replacement pool for weapons, equipment, maintenance, and ammunition. Then, like the enormous shakos and hussar helmets worn by the soldiers in Napoleon’s Grande Armee, it too faded into history, never to return.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments