By Christopher Miskimon

The U.S. Army entered the war in North Africa in November 1942, eager to engage the German and Italian armies and prove itself their equal. In the months to come it would be introduced to combat and would learn hard, expensive lessons along the way.

Many American soldiers would receive rude shocks about the true nature of modern combat, the inadequacies of some of their weapons and equipment, and the raw inexperience of not only themselves but their leaders as well. It was a tough period for the Army, but it was also a tempering one, a forge that would begin to shape and harden men into the weapons they needed to be to carry the fight from Tunisia to Germany itself.

Lt. Col. John Waters and the 1/1

The 1st Battalion, 1st Armored Regiment (1/1) of the 1st Armored Division was one of the units destined to enter this crucible; its initiation into combat included a number of smaller engagements that led to the first tank battle between a regular American armored unit and the panzers of the German Army (a small detachment of American tankers had in fact served with the British earlier in 1942 in order to gain experience). The 1/1 could trace its lineage back to the 1830s and the U.S. Regiment of Dragoons through various cavalry units until it finally became the 1st Armored Regiment in July 1940. In May 1942, the unit shipped to Ireland and began training until its eventual movement to England and the selection of its parent division to take part in Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa.

The 1st Battalion was equipped with the M3 light tank, now commonly known as the Stuart, though during the war American tankers rarely if ever used this British-applied name. The other two battalions of the regiment used the larger M3 medium tank, standard organization for an armored unit at that time. The men of the 1st knew their tanks were smaller than their medium counterparts, but they still tried to undertake the same missions.

The M3 was reliable, quick, and agile. The crews had trained with them for many months and knew them well. They were aware the tank had some shortcomings. Its narrow track made for tough going on soft ground, and it had poor visibility when buttoned up, all hatches closed. The men had taken comfort, however, in the tank’s armor and also in its diminutive 37mm cannon. They would soon discover the extent of their misplaced faith.

The battalion commander was Lt. Col. John Knight Waters, son-in-law of the soon to be famous General George S. Patton, Jr. Serving under him was 29-year-old 2nd Lieutenant Freeland A. Daubin, a platoon leader in A Company. Daubin would bear witness to the battalion’s first fights and later write an extensive firsthand account of the action.

Fighting for Tafaraoui Airfield

In October 1942, more than 70,000 American soldiers boarded transports destined for the shores of North Africa, and the men of the 1/1 were among them. The soldiers loaded their light tanks aboard three oil tankers that had been converted into the first landing ships, tank (LSTs) of the war, under the flag of the Royal Navy. The soldiers were unaware of their destination as the convoy set out for Oran, Algeria, escorted by five armed trawlers.

After 20 days, the ships arrived offshore and the landings began. The battalions equipped with light tanks, including the 1/1, were landed first because the landing craft available could not carry a tank as large as the medium M3 Lee. The medium tanks would wait in the holds of transports until a port had been secured. In the confused fighting that took place against the Vichy French forces, the battalion was ordered to take control of the Tafaraoui airfield, about 10 miles south of Oran itself.

On November 8, Colonel Waters moved his unit there and secured it, preventing interference by the landings of the Vichy air force. B Company, under the command of Captain William Tuck, a Georgian, was the first unit of the battalion to arrive at the airfield. They got to the field without resistance, but the French started shooting at them with antiaircraft guns when they were partially across it. Luckily, the guns could not depress far enough to hit the American tanks.

“The action there only lasted an hour and it was not very intense,” Tuck said. “We considered it intense at the time…. We had a lot to learn.”

The French responded the next day by ordering a column to advance north toward the airfield from the Foreign Legion post at Sidi-bel-Abbes. This force was mechanized and included a number of Renault R35 tanks. Aerial reconnaissance spotted the column as it wound its way north, continuing despite attacks from Allied aircraft. The 1/1 was ordered to intercept the Vichy force, so Colonel Waters deployed his tanks south down the road the enemy column traveled.

The two columns met and engaged near the town of St. Lucien, about seven miles southeast of the airfield. Tuck’s B Company, again in the lead, was deployed with two platoons in front and the third about 500 yards behind, supported by some T30 half-tracks carrying 75mm pack howitzers. The French force had time to take up defensive positions atop a small hill. A sharp but one-sided tank battle ensued, in which the French tankers were badly defeated.

Tuck laid down a base of fire with one platoon while the other two assaulted the Vichy position from the right. The French rounds bounced off the M3s while the American rounds penetrated. At the cost of only one American wounded and one tank damaged, B Company knocked out 14 R35s, many of them set afire. Tuck belatedly realized that, if the French tanks had been equipped with effective cannon, his company would have taken heavy casualties; he resolved to fight more wisely in the future.

“Do Not Slack Off in Anything”

After the fighting against the Vichy French ended, the men were quite pleased with themselves and the performance of the battalion. This quickly developed into what some thought was a careless attitude toward the upcoming showdown with the Germans. This was of great concern to Colonel Waters, who addressed his men on the subject and warned them not to get too cocky. Daubin remembered Waters telling them, “We did very well against the scrub team. Next week we hit German troops. Do not slack off in anything. When we make a showing against them you may congratulate yourselves.”

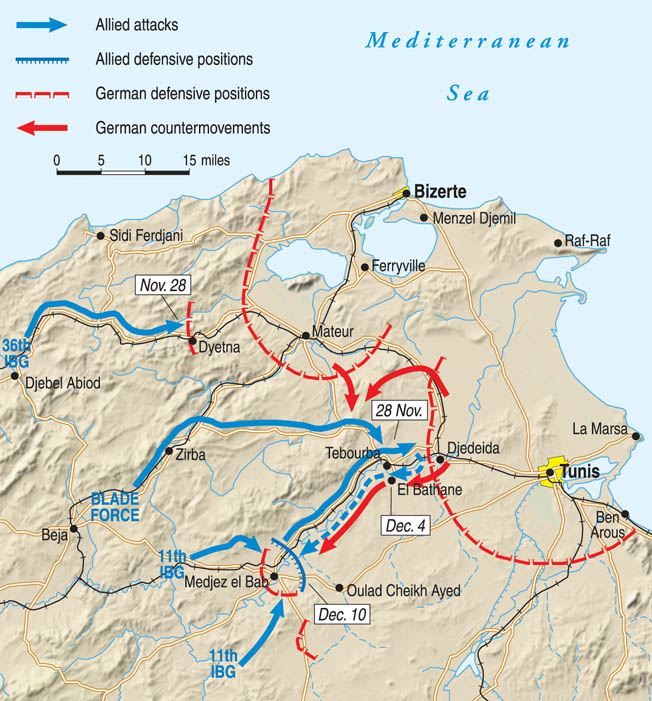

Afterward, the 1/1 loaded its tanks aboard trains and the troops into a truck convoy and began the trip into Tunisia to meet that German foe at last. Offloading at Souk Ahras, the battalion became part of the Allied effort to occupy Tunisia and block the retreat of General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps, thought to be pulling back in preparation to evacuate North Africa. Allied intelligence estimated the Germans were evacuating as many as 10,000 troops a day through Tunis and Bizerte and that the remaining soldiers were poorly equipped and had only obsolete tanks. Instead, Axis reinforcements were pouring in and preparing to fight.

As Daubin later reflected, “The figure 10,000 proved to be correct, except that they were coming in—not leaving.” As the unit made its way east, it came under sporadic air attack. Tuck recalled that the battalion quickly learned to spread out its vehicles to reduce the danger. Along the roads, British engineers had placed signs: “Don’t sit and die—jump and run.”

Assigned as part of the joint British-American battle group nicknamed Blade Force, the battalion bivouacked north of the town of Beja. There it joined with a British armored regiment, the 17/21st Lancers, and prepared for the advance. Morale was still quite high, and many of the men expressed fears that the Germans might escape before the Americans could get a shot at them. Waters reported to Beja, headquarters for the Blade Force, to receive his orders.

Those orders turned out to be some of the vaguest instructions any battalion commander ever received. He was told to create a “tank infested area” around the Chouigui Pass, which connected the Tine River valley of northern central Tunisia to the Plain of Tunis. Just how to “infest” the area with tanks was not explained; there was a sense, however, that the area was perhaps a soft spot in the Axis line. The difficulties were many; air and artillery support were almost nonexistent, save the battalion’s own mortars and howitzer-toting halftracks.

Likewise, there was no infantry support, a severe limitation for an armored unit that depended on infantry to help protect it from enemy antitank guns. Supplies would have to be brought up from Beja, over 30 miles to the southwest. Still, with such orders Waters would have a chance to exercise his own initiative and discretion. His troops were soon to come up against the main team he had warned his men about.

Defending “Chewy Gooey Pass”

The 1/1 moved out the next morning, November 25, 1942, forming the right side of the advance alongside the Lancers as they spread out across the floor of the valley. German aircraft flew overhead but, intent on their assigned targets, ignored the armored force below them. The area was full of rugged hills that were cut by the narrow, three-mile-long Chouigui Pass (quickly renamed by the troops as “Chewy Gooey Pass”); it was a key feature of the area that Waters realized would have to be held in order for the battalion to accomplish its task. A hard-surfaced road wound its way west from the town of Chouigui through the pass before turning north to the town of Mateur.

Waters quickly deployed his three companies, assigning A Company, under Major Carl Siglin, the task of holding the west end of the pass to protect against any German advance southward down the road from Mateur. B Company, under the now Major Tuck (all the company commanders had been promoted after the actions around Oran but as yet remained in command of their companies) would hold the eastern end of the pass facing Chouigui. Major Rudolph Barlow, the C Company commander, would take his tanks on a reconnaissance to the east of the pass.

Assault on a Farmhouse

While the companies carried out their missions, two Italian tanks were spotted coming south down the road from Mateur, apparently trying to scout out the American positions. Lieutenant “Red” Yale, a platoon leader in Headquarters Company, led the tanks of the battalion command section against them and quickly knocked them out. While he was doing that, the battalion reconnaissance platoon discovered an enemy-occupied farmhouse about one and a half miles north of the pass on the Mateur road. Consistent with farmhouses in the area, it was actually a small complex of buildings surrounded by a stout wall. As much a small fortress as a farmstead, it was built to resist the depredations of local raiders and bandits and would now prove just as resistant to American soldiers.

Major Siglin’s A Company was ordered to attack the farmhouse but not to become so heavily engaged they could not carry out their primary mission of defending the western end of the pass. Siglin ordered his first and second platoons forward, and the battle began. The German defenders opened fire with rifles and machine guns, having little effect on the tankers. Unfortunately, the fire from the cannon and machine guns of the Stuarts had little effect on the stout walls of the farm. The tanks then came under fire from several antitank guns concealed in a cactus hedge near the complex’s front gate. The Americans returned fire to suppress the enemy gunners. Soon one of the Stuarts had been knocked out and another disabled.

Lieutenant Daubin took his 1st Platoon command tank through a vineyard on the south side of the farm and right up to the enemy-held wall. In front of that wall was a trench line filled with German defenders, who popped up to fire at Daubin’s tank with rifles and submachine guns. Daubin opened fire in return, killing many of them. Now, at point-blank range from the wall, the tank began to take fire from more German riflemen who were poking the barrels of their Mausers through loopholes in the stone. The experienced German troops quickly knocked out every vision prism on the tank, forcing Daubin to take risky glances out of the hatch.

One loophole obviously contained a machine gun, and Daubin fired several 37mm cannon rounds directly into it, apparently disabling the enemy gun. However, he noticed that with the last shot from his cannon its recoil mechanism froze, leaving the 37mm gun stuck out of battery and now useless. As Daubin tried to reform his platoon to continue the attack, orders came over the radio to fall back and return to the pass. His tank was covered with rifle and machine-gun bullets that had hit the tank, flattened out, and stuck to the hull, causing the Stuart to look like it had a “three day growth of beard.”

With the tank platoons pulled back, the farmhouse was shelled by the assault gun and mortar platoons. As showers of red terra cotta-style tiles were blown from the roof with every hit, there was little other effect and the bombardment was soon ceased. Without infantry or artillery support, the farmhouse would remain in German hands, though under surveillance. A Company resumed its defensive positions at the pass.

The Luftwaffe Strikes

Soon after A Company had returned to its positions, a solitary German Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bomber appeared overhead. Flying low over the position, it dropped a single bomb to no real effect and flew away. Soon after, however, a squadron of enemy planes, a mix of Ju-87s, Ju-88 bombers, and Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters came overhead and attacked the company; apparently the lone plane had been a scout testing the defenses.

Daubin noted with pride that every one of the .30-caliber antiaircraft machine guns in his platoon was quickly manned to repel the German attack. His pride succumbed to dismay when every one of the guns immediately jammed. The boxes holding the belts of .30-caliber ammunition were slightly wider than the length of the rounds; the bouncing and vibrations of the tank during normal movement had caused some of the rounds to work loose from the belts, causing jams. Daubin’s gunner got off about 10 rounds between three jams as a Stuka dived toward them on a strafing run.

Nearby, the company first sergeant, Henry Surowski, climbed atop the command half-track and manned its .50-caliber machine gun, firing bursts at the planes when they swooped down on an attack run. The men in the company maintenance section clustered around their own half-track, firing away with their 1903 Springfield rifles. The air attacks went on for several hours as the enemy planes returned after rearming. Many of the American troops sheltered in a nearby wadi until a lucky hit sent debris and rocks flying into it.

Daubin and his machine gunner reloaded their gun with a fresh belt from inside the tank and let loose on the next plane to fly over them. Leading their target, they watched as their tracer rounds seemed to impact the nose of the enemy plane but it flew off, seemingly unaffected. Unfortunately, the effort seemed to draw the attention of the next plane, an Me-109 that strafed them as they stood exposed atop their M3. Both of them jumped off the tank and took cover with the rest of the platoon.

An errant bomb struck a nearby hillside, landing in the middle of a herd of goats, wounding or killing almost all of them. Their piteous cries were heard by the entire company until one soldier could take no more and went up the slope with his rifle, putting the poor creatures out of their misery. A Stuka pilot flew slowly and defiantly overhead, shaking his fist at the Americans as his machine gunner in the rear cockpit fired.

Saving Smith

Soon after, the raid was over. The troops moved around, checking for casualties and damage to their precious vehicles and equipment. A Company had been relatively lucky; no tanks knocked out, a few light wounds, and only one man dead. While checking, however, they found that a man from the 3rd Platoon was missing, a soldier named Smith who had a brother in the company. Smith had been a crew member of the Stuart tank knocked out earlier at the farmhouse. Because his wounds made him unable to move to safety during the battle, he had threatened to shoot himself if his fellow soldiers had risked themselves to move him. His tank commander, a sergeant named Smarts, had grudgingly agreed to leave him, though the platoon had returned later in their tanks to look for him. As nightfall descended, the search had been called off for fear of crushing the man under the treads of the searching tanks.

Major Siglin, however, refused to give up on the soldier. He asked for a volunteer who knew Smith’s rough location to go with him to get the man. Immediately Sergeant Smarts stepped up, and the two set out in the major’s jeep.

The rest of the company watched as Siglin and Smarts risked their lives to save the wounded Smith. It was not yet completely dark, and a number of nearby haystacks had been set ablaze by the day’s fighting, giving the Germans good visibility of the rescue attempt. Quickly three of their machine guns opened fire on Siglin’s jeep, white tracers flashing about it. The odds seemed heavily against the two men. Then bursts of pink tracers began racing back toward the Germans; Sergeant Smarts was firing back with the jeep’s .30-caliber.

This tiny but ferocious battle went on for a few minutes. The jeep came limping and sputtering back to the American positions, steam escaping from its punctured radiator, three tires flat and flapping. Siglin and Smarts had found Smith and brought him back, and not one of them had been hit in the attempt. It was an inspiring and heroic act on the part of the two men.

Taking the Bridge at Tebourba

While A Company was fighting its battle at the farmhouse and enduring air attacks, C Company was conducting its reconnaissance east of the Chouigui Pass. Its orders included checking the condition of two bridges in the towns of Tebourba and Djedeida. Both bridges crossed the Mejerda River and provided routes to the east and Tunis. In accordance with the mission of “infesting” the area, Major Rudolph Barlow, the company commander, was authorized to engage any enemy formations encountered if practical. These orders were to prove fortuitous and would lead to a number of successful engagements.

The first occurred as the company moved through the pass. Halfway to the eastern end, a small German scout detachment of several cars was encountered. This group was quickly destroyed, and the company continued eastward. The town of Chouigui lay at the eastern end of the pass, and the American tankers moved right in, gaining complete surprise over a company-sized element of German reconnaissance troops in more cars and motorcycles. Caught unaware, these troops were quickly cut down by the cannon and machine guns of the American M3 tanks. Bodies and wrecked vehicles soon littered the town.

With two successful engagements under the unit’s belt, Major Barlow then pointed his company south toward Tebourba. Moving at full speed, they made for the bridge. A small detachment of Germans guarded it, and within minutes they succumbed to the superior fire of the American tanks.

Barlow’s remaining objective, the bridge at Djedeida, was five miles to the east. He reasoned that by now the Germans in the area must be alerted to his presence. He moved his company off the road and into adjacent olive groves, providing some concealment. After just two miles the groves thinned out, but Barlow continued, his advance guard led by a Lieutenant Hooker.

Barlow’s Hard-Charging M3s

Hooker’s platoon moved ahead of the rest, stopping on a ridge to survey what lay beyond. What the Americans saw both astounded and excited them. A German airfield lay spread out before them, dozens of planes parked and vulnerable. Ironically, this was the same mixed force of fighters and bombers that had attacked A Company earlier in the day.

Hooker reported his find to Barlow, who took the initiative and quickly brought his company on line to attack the airfield. The major placed his tank at the center of the line, with Hooker’s platoon on his left and another commanded by Lieutenant Bud Hanes on the right. Lieutenant “Daniel” Webster’s platoon formed a second line and followed the first in. Their hasty plan completed, the company roared off the ridge and attacked the airfield.

C Company’s charge was reminiscent of a horse cavalry charge from a history book or a Western, and the result was utter chaos for the Luftwaffe troops below. Resembling “fat geese on a small pond,” the German planes were destroyed by the U.S. tankers. Cannon and machine-gun fire poured from each tank, riddling enemy planes where they sat. A few tankers took their M3s and crushed the tails of fighters under their treads.

One tank quickly moved to the end of the runway. Some of the German pilots were desperately trying to get their planes airborne before they were destroyed. As each enemy plane tried to take off, the tankers fired a round of 37mm canister into the cockpit area. After such a hit, the plane would careen out of control and crash in a ball of flame. Some of the enemy pilots were so intent upon escape that they crashed their planes into one another. Still others made for an almost comical scene as they tried to taxi away from the field, an M3 chasing each down to destruction. Eleven planes were quickly destroyed, and only two got off the ground.

Major Tuck, dug in on the east end of the pass, could actually observe the fight and had been relaying radio traffic from Barlow back to Waters. “Rudy [Barlow] called me and said, ‘We’re laying down a base of fire now and we’ll be attacking.’” Members of B Company watched the attack unfold, seeing their brethren rampage over the airfield.

On the German end, the attack indeed caused quite a shock. Some Germans had thought the oncoming tanks were friendly at first, and even waved at them. When the attack began, Arndt-Richard Hupfeld, an Me-109 pilot of Jagdgeschwader (fighter squadron) 53 mistook the attackers for a British unit and recalled, “There was a mad scramble when British tanks attacked our base. Messerschmitts took off in every direction. Suddenly I saw a 109 coming straight toward me.—A head-on collision would have been unavoidable had the other aircraft’s cowling not flown off just as it was about to lift off, whereupon the other pilot closed the throttle and did not take off. I just cleared the other aircraft and thus avoided a catastrophe.”

With the airfield personnel driven off or killed, the tankers turned their attention to the nearby hangars with more planes, fuel stocks, repair shops, and other supplies. All of these quickly went up in flames. The final count stood at 36 aircraft of all types destroyed, not including a number of planes still in crates in the hangars. The two planes that had taken off lingered a while to strafe the American tanks; they killed two tank commanders, including Lieutenant Hanes, as they stood vulnerable in the hatches of their M3s.

One other tank disappeared entirely; no one in the company saw it or the crew again. Deciding they had done all they could for the day, Major Barlow pulled his company back to the Chouigui Pass. C Company had dealt a serious blow to the Germans, destroying over a company’s worth of enemy ground troops and dozens of valuable aircraft the Luftwaffe sorely needed to defend against the American advance. The next year Major Barlow received the British Military Cross for the action, although strangely, no publicity was given to this award. The Germans were dismayed by the report of this attack, received at the same time as a false rumor about American tanks nine miles outside Tunis.

“Happy Valley”

With darkness overtaking the area, Waters situated his battalion for the night. He had been informed that the 1/1 would now become the Blade Force reserve. C Company was positioned on the east side of the pass as a guard force. A Company was situated high on a hill, three-quarters of a mile south of the western end of the pass while B Company was placed slightly north of the same entrance.

At dawn Major Tuck placed his company on the reverse slope of a ridge that paralleled the roadway. Carefully, he positioned every tank hull-down so that only the turrets stood above the crest of the ridge, enabling them to sweep the road with cannon fire. The road itself lay only 50 to 100 yards from their position. Headquarters Company was two miles to the west at a complex known as Saint Joseph’s Farm. The tankers of A Company had christened the area “Happy Valley,” after the air attack they had endured earlier. The rest of the battalion quickly took up the ironic name.

Facing the Germans’ Newest Panzers

The day began quietly, the soldiers drinking tea and smoking ersatz cigarettes made from leaves rolled in toilet tissue. A flight of German bombers came overhead but passed by. Major Siglin left A Company to go the battalion command post. Daubin, Lieutenant John Deck, the company maintenance officer, and First Sergeant Surowski were at the command halftrack talking when they saw movement on the road, coming their way. Daubin and Deck had trouble making out what was approaching, equipped as they were with older-model low-magnification binoculars. The first sergeant, however, had liberated a pair of French naval binoculars in Oran, much more powerful than what the officers had. What he saw through them excited him, and he passed them to Daubin.

A cloud of dust had reached the walled farm where they had fought the day before. Dimly visible through the dust were a number of vehicles, each with what appeared to be a long boom extending from it. The three men concluded it had to be a German engineer unit unaware of the American presence ahead. If they continued along the road they could be ambushed easily.

Their hopes were dashed as enemy shells began to land among the company. They had been spotted, and not by a unit of engineers. Instead, the approaching Germans were a unit of Panzer Battalion 190 with 13 Mark IV tanks, equipped with long-barreled 75mm cannon the American tankers had never seen before. The standard Mark IV had a short-barreled 75mm L24 cannon, a relatively low-velocity weapon primarily intended for firing high-explosive rounds in a support role. This new variant, the Mark IV F2, had the much deadlier, longer-barreled L43 weapon and had been in service for only a few months prior to the Operation Torch landings.

Some sources state that the German force was a mixed one of perhaps six Mark IV F2s and a few Mark IIIs, with some Italian armored vehicles in support. While it is more likely the German force was composed of mixed tank types, Daubin’s account mentions only the Mark IVs. In any event, it was a formidable force for the Americans, who were equipped only with light tanks.

Delaying the Enemy

Colonel Waters saw the enemy column from his position at the farm, calling it “a beautiful column, preceded by some pathetic Italian reconnaissance vehicles.” Major Siglin saw the enemy movement as well and quickly commandeered a jeep to get back to the company. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Deck ordered the company to ready for action. The tankers of A Company started their engines, quickly took down camouflage netting, and removed excess gear from their tanks. Now ready to go into action, they sat awaiting their commander’s return.

As they waited, the company had an excellent vantage point for watching an attack on the enemy formation by the battalion’s assault gun platoon. Led by Lieutenant Ray Wacker, this platoon was composed of three 75mm pack howitzers mounted in half-tracks. As the men of A Company looked on, the three vehicles moved across the valley floor in a wedge formation toward the oncoming panzers.

At just under 1,000 yards from the enemy formation, the half-tracks broke out of a small olive grove and set up to fire. Each howitzer’s section chief ran out and set up stakes to aim the weapons. Within moments the center gun was firing ranging shots at the lead German tank. Just as quickly, the range was found and all three cannon opened fire, each firing 10 rounds as fast as it could.

The gun crews had no armor-piercing or antitank ammunition. Nevertheless, they threw high-explosive shells at the closing panzers. The initial 30 rounds all fell close to the first tank, with several direct hits. The tank slowed to a halt, and the American gunners shifted to the second tank, then the third.

The explosions created bursts of smoke and kicked up great clouds of dust. After a few moments, the three lead German tanks moved out of the dust and opened fire on the assault gun platoon. The explosive rounds had proven ineffective against the tanks’ armor. Luckily for the howitzer crews, the Germans were firing armor-piercing rounds that tore into the ground around the half-tracks. If they had fired explosive rounds, the blast and shrapnel would surely have caused loss among the Americans.

Lieutenant Wacker quickly received orders from Waters to withdraw. The assault guns laid a barrage of smoke to cover their retreat and they fell back without loss.

Daubin’s Duel With the Mark IVs

The German armored column had not been stopped, but it had been delayed long enough for Major Siglin to return to his unit and plan his attack against the German right flank, while B Company across the road would fire on the German left flank from its hull-down positions.

Siglin mounted his command tank, Iron Horse, and prepared to lead his company in the attack. Daubin’s 1st Platoon now had only three tanks; none of them had working radio transmitters. He commanded the center tank so he could direct the other two tanks with hand and arm signals. His platoon sergeant, Bud Hall, and another sergeant named Schwartzkopf commanded the other tanks. They smiled encouragingly at their leader.

Daubin later wrote with a sense of pride, “I don’t believe any lieutenant ever commanded a better combat platoon than this one.” His platoon moved out on the right flank of the company.

As they moved through the scattered olive trees, Daubin spotted an Italian light tank a few hundred yards on the flank of the German column. He stopped his M3 long enough to put two rounds of armor-piercing ammunition into it. A third round, this time high-explosive, set the enemy tank afire. Daubin noticed, however, that several of his company’s tanks were now burning as well.

The German tanks had barely had time to move out of their column formation, so quickly had A Company launched its attack. The long barrels of their cannon were pointed at the approaching M3s, and now they replied with their own deadly fire.

Daubin pulled his tank into a small wadi for partial cover from the German fire. He selected an enemy tank, only 140 yards away, as his target and opened fire. Armor-piercing 37mm rounds flew at the Mark IV as quickly as the crew could load and fire. The German crew located Daubin’s tank and turned its tank head-on, putting its thick frontal armor toward the attacker.

Even though the little M3 was well within the Mark IV’s range, the Nazi crew moved forward, closing the range. The M3s gun popped and snapped like an angry cap pistol. The loader jammed rounds into the breech, and Daubin fired them, practically unable to miss at such close range. He watched as the tracers from his armor-piercing rounds flew into the hull of the German tank and then bounced away in a shower of sparks. The now desperate American crew fired 18 rounds at the German. None of them penetrated its hull or turret.

At 50 yards the German tank fired, but, surprisingly, the round fell short, hitting the bank of the wadi and bouncing away. Daubin later mused that the “German gunner must have been addled or the gun not bore-sighted for such short ranges” for the shot to have missed. The German tank now closed to 30 yards, mounting a small rise that robbed the M3 of what little cover it had. Daubin ordered his driver to back out as fast as he could and to zigzag in order to throw off the German aim, but to keep the frontal armor facing the enemy. The driver calmly replied “Yes sir!” and started to back the tank out of the wadi.

Then the Germans fired again. This time, the round struck home, crashing through the front of the M3’s hull. The driver was killed instantly; the bow gunner was stunned and blinded. Daubin was blown out of the commander’s hatch and thrown clear, alive but seriously wounded. The loader scrambled out of the tank as it erupted into flame, only to be cut down by machine-gun fire as he tried to find some cover from the panzer. The Germans turned their machine gun against Daubin next. He scrambled into the wadi. His flaming tank eerily continued to back away as Daubin watched, waiting for the enemy tank to come and finish him.

The Germans were not going to get their chance, however. Turning to face the attack by A Company, the Germans had exposed the thinner rear armor of their tanks to the fire of B Company, sitting in their hull-down positions on the ridge. They pumped cannon fire into the enemy. One of Tuck’s tankers reported a hit on one of the German tanks that quickly started a fire. Tuck asked where the gunner had aimed and was told to aim right behind the tank’s drive sprocket.

Other members of the company did so and began knocking out German tanks. Accounts vary, but between four and nine of the 13 German tanks were knocked out. No matter the number, it was enough. The rest of the German armor fled back in the direction from which it had come. Tuck attributed the amazing precision of the B Company fire to the accuracy of the 37mm gun, weak though it was in penetrating power. Half the A Company tanks were destroyed in the engagement. B Company, springing its ambush, had escaped unscathed.

Evacuating the Wounded

The two companies now combined their tanks and moved toward the enemy-held farm. German infantry had been spotted dismounting from trucks there. The infantry had moved into the vineyards near the farm, where the American tankers hunted them down. All but two of the remaining German tanks had fled, exposing the German troops to the American attack.

The last two German tanks took refuge in the farmyard. It would be to no avail. With momentum, the Americans forced open the gates of the farm and rampaged through the grounds, shooting Germans off the parapets. Tragically, during this fight Major Siglin was killed, an enemy cannon round piercing his turret. Iron Horse’s sergeant, an Apache Indian named Guierro, brought Siglin’s body back to Saint Joseph’s Farm. Without saying a word, tears streaming down his face, he deposited his commander’s body, reloaded his tank with ammunition, and returned to the battle.

As the fight continued, Dr. Benjamin Cohen, the battalion surgeon, cruised the battlefield in his medical half-track searching for the wounded. Accompanying him was the unit’s chaplain, Father Brock. Ignoring the enemy fire, they went from tank to tank, rescuing their wounded crewmen and picking up others wherever they lay. After shooting up the farm complex, the tankers withdrew, lacking the infantry needed to hold it. That night, the remaining Germans withdrew to Mateur, eight miles north. Later, their commanding officer would be court-martialed for withdrawing without orders.

A Company was turned over to Lieutenant Deck, and he was later promoted to captain. Daubin was evacuated by ambulance to a British hospital some 100 miles to the rear. On the litter below his was a captured German lieutenant, a crewman from one of the destroyed Mark IVs. Both the German and a British medic spoke French, and the medic translated so the two officers could speak. The German haughtily told Daubin that America would lose the war because its tanks were so inferior. The American pointed out the German’s status as a prisoner, and the enemy officer cursed and went silent.

Twice during the trip Luftwaffe aircraft strafed the ambulance and its convoy. Each time the German soldier laughed. Daubin asked what he was laughing at; his own air force was trying to shoot him. The German said in response that since Daubin was in the litter above, the American would die first. Daubin conceded that he had a point. Later, he discovered why his unit’s 37mm weapons had performed so poorly even at point-blank range. In the chaos of its first operation, his battalion had been issued training ammunition instead of the newer armor-piercing rounds, which were still sitting in the supply depots of Algiers.

Tankers on the Long Road to Victory

The first major combat between American and German tankers was over. Both sides had sustained losses, and the battle is perhaps best considered a draw. However, one should consider that the relatively inexperienced Americans had repulsed an assault by veteran German tankers in superior machines and still held the pass at the end of the day. In addition, they had ravaged a German airfield, destroying precious aircraft and stocks of supplies.

The 1st Battalion missed the debacle of the Kasserine Pass while refitting in Oran. Although much hard fighting lay ahead, the Americans had started down the long road that would lead to Sicily, Italy, France, and eventually to Germany itself.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments