By John E. Spindler

Denis de Morbecque, an exiled French knight in the service of the English crown, thought the fighting in the hawthorn hedgerows near Poitiers would never end. Prince Edward, the leader of the Anglo-Gascon army, had instilled the courage in his soldiers to overcome a mounted charge by French men-at-arms and survive the grueling two-hour melee with French knights that followed it. When the English succeeded in repulsing the first division led by Dauphin Charles, victory seemed near. Yet French King John II attacked with a second division of soldiers, and Edward’s weary men fought on in a grim struggle for survival.

Having spent the last five years in English service, the past one under Prince Edward’s banner, Morbecque knew his commander had a plan. At a critical moment during the French assault on September 19, 1356, the prince counterattacked. Unexpectedly, the French army broke. Only small groups of resistance remained. Like every man in the Anglo-Gascon army, whether an English lord or a Gascon spearman, Morbecque searched for the French king in the hope of capturing him.

The capture of King John would not only end the battle, but bring fortune upon that individual. As Morbecque fought on, he observed a French knight who was still gallantly fighting. He had already seen a handful of French knights dressed identically; however, this knight wielded a battle-axe with an exceptional amount of skill. Sensing it might be the French king, Morbecque made his way over to his position just about the time the knight’s helmet came off. The knight was indeed the king of France.

King John wished to surrender directly to his cousin, Prince Edward, and he inquired as to the location of the prince. Morbecque informed him that although Prince Edward was not nearby, he could take the French king to his cousin once he surrendered. King John inquired as to his captor’s name and background. “I surrender myself to you,” the king said, handing Morbecque his righthand glove. He had the unfortunate distinction of being the first and only French king captured by England.

By the time of the clash at Poitiers, England and France had been fighting in what would be known as the Hundred Years’ War for two decades. The seeds for this conflict can be traced back to the Norman conquest of England in 1066. William I ruled both England and Normandy. English King Henry II became king of England, Duke of Normandy, and Count of Anjou in 1154. Through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II also acquired the Duchy of Aquitaine, which included the province of Gascony. Yet by the first part of the 14th century, English holdings on the Continent had been drastically reduced and all that remained was the Duchy of Aquitaine, which included the prosperous province of Gascony with the bustling port of Bourdeaux.

England possessed a steady monarch in Edward III who ascended to the throne in 1327. France, however, experienced considerable disorder. The situation was exacerbated when French King Charles IV died in 1328 without a male heir. Through the intricacies of intermarriage among Europe’s royalty, the closest male relative of Charles was Edward. This prospect disturbed the French nobility, spurring them to change the rules in inheriting the throne. The French crowned Philip VI as their king later that year. As the Duke of Aquitaine, Edward was a vassal of the king of France.

Philip resolved in 1337, however, that the Duchy of Aquitaine, must revert back to France on the grounds that Edward had not fulfilled certain obligations as a vassal. The English king responded by challenging Philip’s right to the throne, which ignited the Hundred Years’ War. An English fleet routed a larger French fleet in the Battle of Sluys fought in June 1340. For the next several years, fiscal challenges prevented Edward III from invading France.

Edward launched his first major invasion six years later. Landing in Normandy on July 12, 1346, his expeditionary force quickly captured Caen. While Edward marched east towards Flanders, Philip issued a call to his nobility to assemble an army. In late August, the two armies clashed near Crecy.

One of Edward III’s subordinate commanders at Crecy was his eldest son, Prince Edward, better known to history as the Black Prince. The Black Prince, assisted by the earls of Warwick and Northampton, led the English vanguard. The English force that Philip eagerly sought to engage in battle differed in both tactics and composition.

In lieu of the conventional clash of mounted men-at-arms, which included knights and squires, the king employed tactics honed from fighting the Scots. He ordered his armored cavalry to fight dismounted. In addition to men-at-arms, a significant portion of England’s army consisted of archers who were skilled in the use of the longbow, a weapon unique to England and Wales. Although it took a decade to master the longbow, an experienced longbowmen could fire his weapon faster and farther than a crossbow. As if that were not enough, the longbow had greater penetration power than the crossbow.

The English longbowmen at Crecy dug pits in front of their positions and outfought the Genoese crossbowmen employed by the French.

As the battle progressed, Philip grew impatient and ordered his mounted knights to advance before the rest of his army was properly positioned for attack. The English archers shattered numerous uncoordinated charges by the mounted French cavalry. English men-at-arms easily cut down the small number of French who reached the English line. After his decisive victory at Crecy, Edward resumed his march and captured Calais on August 3, 1347.

Both sides signed the Truce of Calais, openly welcomed by both monarchies given that their treasuries were drained from the costs of war.

Although the truce was extended to 1355, small-scale clashes still occurred.

When Philip died in 1350 the throne passed to his son, Duke John of Normandy. Crowned John II that September he was so well regarded among his subjects for his festive nature that he earned the nickname “The Good.” The new king declined a chance to end the war in April 1354 by refusing to ratify a new agreement, known as the Treaty of Guines. As a resumption of the war seemed inevitable, King John established garrisons and built new fortifications at crucial locations in northern France. Yet his attempts to raise a field army failed owing to a chronic lack of funds and disunity among the French nobility.

England was not the only kingdom with which John had political problems. The Kingdom of Navarre, located in the western end of the Pyrenees Mountains, was ruled by Charles II who possessed land in Normandy. A failed peace in 1354 led to Charles forging an alliance with England’s Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster. Another try for peace collapsed when John arrested Charles while the Navarrese king was attending a banquet held by Dauphin Charles. This impetuous move cost the French king considerable support in Normandy.

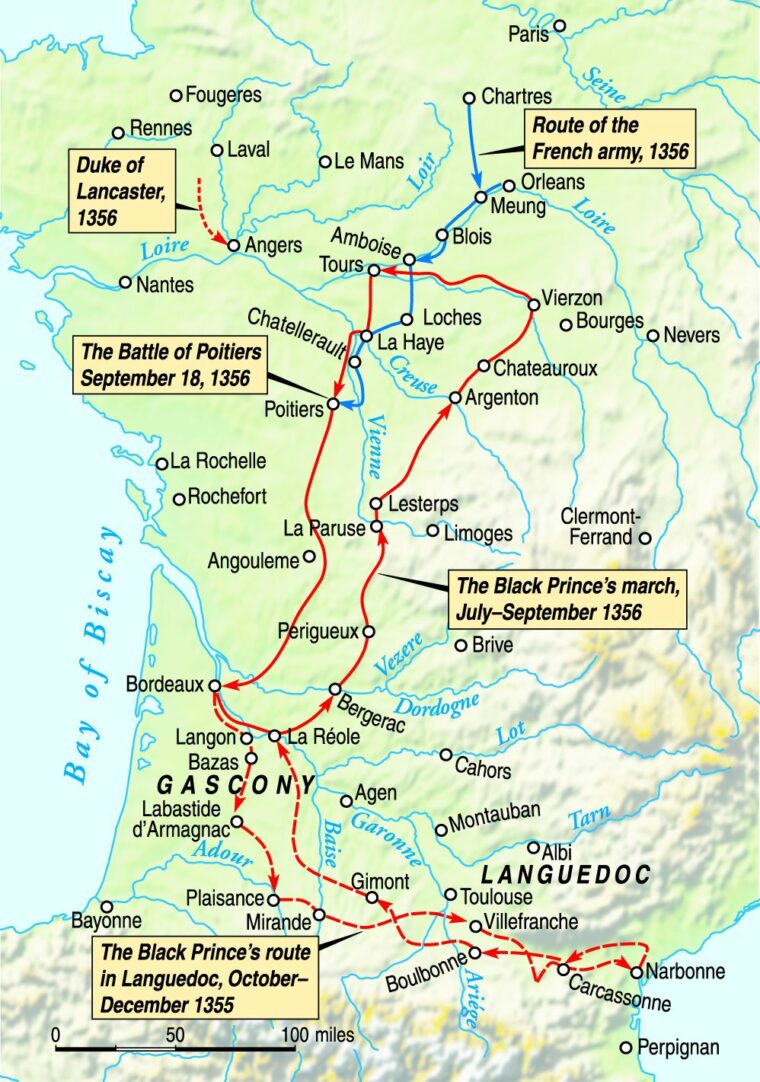

A prominent Gascon nobleman known as Jean III de Grailly journeyed to Edward’s court in January 1355 to request English troops for an offensive against the French in southwestern France. Grailly held the title of Captal de Buch, and as such was the lord of the port of Buch in Gascony. Up to that point, the Gascons had been holding their ground against the French, but de Grailly feared that French raids would increase in scale. Familiar with the Black Prince’s feats at Crecy, de Grailly requested that Edward send the prince to lead the English expeditionary force. Edward III agreed to the proposition, and in April he ordered operations against the French to begin in both Normandy and Gascony. Crossing into France, Edward’s Anglo-Gascon force terrorized the Languedoc region, marching southeast then turning east towards the Mediterranean Sea. The invaders lived off the land, sowing further devastation to a region still recovering from the Black Death. Having encountered little resistance, Edward reached the wealthy city of Narbonne in the Occitanie region on November 8. The fast-moving strike force did not include siege engines, so Edward did not attack the walled city. The French made their first attempt to intercept the English near Toulouse on November 20. In the clash that unfolded, Edward defeated the French. The raid ended with his return to the safety of Gascony on December 2. In the course of his grand chevauchée, the Black Prince had sacked and torched 500 towns and villages.

By early 1356 French forces had retaken 30 towns and castles lost to the English. In spite of being able to retake villages, the French crown was bankrupt. After Prince Edward’s 1355 arrival in Bordeaux, John had suspended debt payments until the following Easter. The Black Prince intended to resume his raiding the next year on the hope of inflicting even greater damage on the French. King Edward provided the funds necessary for chevauchées in Normandy and Gascony, and he sent his son 600 more archers.

As a result of King John’s actions in Normandy, including besieging the city of Breteuil, Norman nobles appealed to Edward III for aid. The French king altered his plan from operations in Brittany to Normandy. In conjunction with Lancaster’s campaign, Edward issued orders for an army to mass in Southampton ready to sail for Calais. From there the English army would drive towards Paris with Lancaster. Any chance of Edward’s participation disappeared when an Aragonese naval force, allied to France, arrived in the English Channel and disrupted operations.

Wanting to help, the Black Prince received orders to conduct another chevauchée into southern France. The French knew Prince Edward planned on conducting another chevauchée, but they did not know where.

Edward’s army arrived near the end of July at Bergerac on the Franco-Gascon border with 4,000 men-at-arms, 3,000 archers, and 2,000 Welsh, Irish, and Gascon foot soldiers. The Black Prince entered into French territory on August 4 with the four earls who had guided him so well the previous year. The Captal de Buch commanded the Gascon troops.

A majority of the army, specifically men-at-arms and archers, rode to allow the force to move at a more rapid pace and inflict more damage. Whereas the English and Gascon knights and squires fought with similar weapons and wore comparable armor as John’s men-at-arms, the missile troops differed significantly. The French king hired Genoese crossbowmen, while the Black Prince relied on the legendary longbowmen. A veteran longbowmen could hit targets at a range of up to 350 yards. Although a crossbow might be able to fire as far, it would not be nearly as accurate. Carrying 60 to 72 arrows, a well-trained longbowmen could fire up to 18 arrows a minute, but dared not waste his arrows so quickly. Even the typical six arrows per minute outperformed a master crossbowman’s four bolts per minute.

The Black Prince deceived the French into believing his intentions would be once more to target Languedoc. For the first couple of days, the Anglo-Gascon force moved in a northeasterly direction before turning north. The raiders proceeded to the Vienne River at Manot. Toward the end of the day on August 14, the English reached Lesterps where they encountered the French defenders for the first time. After defeating them, Prince Edward separated his force into a vanguard, middle guard and rearguard that marched spread out over many miles. To counter the English operations, King John responded by assembling a large royal army. The French king focused throughout the summer on defending northern France.

As Prince Edward’s chevauchée had inflicted considerable destruction on southwestern France, King John knew he had to do something. After working out an arrangement on August 20 to conclude the siege of Breteuil, he appealed to the French nobility for its support. He outlined a plan in which existing forces hold the Loire until he brought an army in early September. Troops were to be sent south of the Loire to observe and harass the enemy. His army south of the Loire slowly began to assemble at Chartres under John de Clermont and Arnoul d’Audrehem, both of whom were Marshals of France.

Prince Edward maintained his northward track. He laid waste to a number of villages over the next 10 days, including Le Dorat, St. Benoit, Argentan, Chateauroux, and Issoudon. The English vanguard ran headlong into a 200-man French detachment on August 28. Instead of shadowing the enemy and reporting on their movements as directed, the leader of the detachment made the poor decision to attack the English. In the aftermath of the one-sided affair, just 30 captured French knights survived. The English held them for ransom. The Black Prince learned that the French king was gathering an army and intended to march on Tours.

The French king assembled his army upon reaching an agreement with the nobles in which they and their men would serve the king for 40 days without pay, after which payments would be disbursed. Placing a premium on mobility in order to catch Edward, John opted to leave behind most of the lower-grade infantry. John’s four sons, Dauphin Charles, Louis, John, and Philip rode alongside their father and his brother Philip, the Duc d’Orleans. King John would rely most heavily on Gautier IV de Brienne, the Constable of France, and marshals Clermont and Audrehem for leadership in the coming clash of arms.

After meeting with his division commanders, Prince Edward struck out for Tours, but ran into delays at Romorantin. The English prince allowed himself to become distracted besieging a castle at that location for four days. Arriving on the southern banks of the Loire a few miles west of Tours on September 7, the Black Prince found all the bridges in the vicinity destroyed. Still believing he might join up with Lancaster, Edward camped along the Loire, enduring rainy weather.

Realizing John’s army was moving to intercept him, the Black Prince decided to return to Gascony. He set out on a march south four days later moving at a moderate pace. The prince still wanted to fight the French, but he wanted to do so on terms favorable to him. While the opposing armies were maneuvering against each other, Pope Innocent VI dispatched Cardinal Talleyrand of Perigord to broker a peace settlement.

News arrived that the French had crossed the Loire near Amboise, which placed the English, suffering from low provisions, in a bad spot. The Cardinal of Perigord met with Prince Edward at Montbazon on September 12. The cardinal told the prince that the dauphin had entered Tours with 1,000 men.

Over the course of the next week Edward and John continued to maneuver, each hoping to gain an advantage. John eventually got around Edward. Having learned that the French were approaching Poitiers faster than expected, Edward moved on September 17 to intercept his cousin.

through Languedoc in autumn 1355 and then

launched another chevauchée into northwestern

France the following summer that culminated in

the clash of arms at Poitiers.

Both sides dispatched scouting parties that collided in a sharp skirmish. King John was present at this skirmish, but he retreated to avoid becoming a casualty. Edward knew he had to take decisive action because his provisions were nearly exhausted and his men were thirsty. Scouts informed him that the Miosson River was nearby and that the ground north of Nouaille-Maupertuis offered a good defensive position.

The next morning the Anglo-Gascon army occupied a hill north of the Nouaille Woods, about five miles south of Poitiers, and the parched men quenched their thirst. Being Sunday, the odds of a battle were low, after all the so-called Truce of God forbade fighting on holy days.

Throughout the day, Cardinal Talleyrand traveled between Edward’s position and the French camp three miles to the north. Edward and John could not agree on peace terms. While the cardinal tried to achieve a peaceful solution, both sides prepared for battle. Edward’s 3,000 men-at-arms, 1,000 foot soldiers, and 2,000 archers took up battle positions. The earls of Warwick and Oxford commanded the first division, Prince Edward led the second division, and the earls of Salisbury and Suffolk commanded the third division.

In front of a wooded tract, Edward deployed his divisions behind a hawthorn hedgerow that ran the length of his line and only had one large gap, which the prince defined as wide enough to fit four knights riding abreast. In front of the hedgerow were thickets and vines on a slope. At the bottom of the slope was open ground that rose up towards the French camp.

The English vanguard deployed near the Miosson River on the left flank. It had access to the Gue de l’Homme ford, a ready escape route should one be needed. Warwick, with subordinate commanders Oxford and Captal de Buch, had 1,000 English and Gascon men-at-arms.

To their left, extending along the marshy banks of the Miosson, were 1,000 Welsh and English archers. Situated on the right flank were the earls of Salisbury and Suffolk with 1,000 men-at-arms and 1,000 archers. The archers dug trenches and overturned wagons to serve as field fortifications. Edward’s division consisted of the Gascon foot soldiers and 1,000 men-at-arms. He took up a position with a reserve force of 400 men-at-arms.

John arrived at Poitiers with 8,000 men-at-arms, 2,000 mounted Genoese crossbowmen, and 1,000 light infantrymen. These men-at-arms, the proverbial flower of the French chivalry, and some allied Germans, would battle alongside 200 Scottish knights under Lord William Douglas and 90 members of the Order of the Star, which was King John’s personal bodyguard.

As with the English, the French took advantage of the truce with men arriving throughout day, ranging from 1,000 to 4,000 stragglers. King John listened to the advice of Lord Douglas who had fought the English. The Scottish lord suggested that the French men-at-arms should fight dismounted like the English.

Agreeing with the idea, the king made one alteration. He formed a mounted shock force composed of two companies each with 200 mounted armored men-at-arms. Led by marshals Clermont and Audrehem, their task was to disrupt the English archers at the start of the battle. Following as close as possible behind these troops would be a large French force led by Constable of France, Lord Douglas, and a number of German men-at-arms and the majority of crossbowmen.

King John organized the rest of the army into three divisions. Shortly after the vanguard struck the enemy’s lines, the dauphin’s first division of 4,000 troops would attack. As it was his first battle, the Duc de Bourbon accompanied the dauphin. The inexperienced Duc d’Orleans led the second division composed of 3,200 men-at-arms. King John took command of the third and last division. Accompanying the king was his son, Phillipe, standard bearer Geoffrey de Charny, 2,000 men-at-arms, and a small number of the Genoese crossbowmen.

The sun rose at 5:40 a.m. on September 19. The English and Gascons woke hungry, having slept in or near their defensive positions. Over the next couple of hours, both armies were active.

Prince Edward had mass performed while Cardinal Tallyrand made one last attempt at peace. John ordered his divisions to form up outside of the longbow’s range. Arming himself with a battle axe, he had 19 knights dress identically to him.

Edward decided that morning to move his baggage train across the Miosson via the Gue de l’Homme ford. The Earl of Warwick provided escort detail. It is unclear whether this was an attempt to move the train to a safer position or whether the prince was trying to withdraw. It might have been neither for the prince may deliberately have been seeking to goad the enemy into making a rash attack. Prince Edward visited the men in all of his divisions, imparting words of courage to each group of soldiers.

King John and his senior commanders began receiving reports that the Black Prince’s banner had disappeared behind the hill. Many of the French commanders assumed that the enemy was retreating and that immediate action had to be taken to prevent their escape. Marshal Clermont and Lord Douglas both advised that the army should maintain its existing position. They believed that Prince Edward was nearly out of provisions and that the French had only to bide their time and the English army would surrender. Audrehem challenged Clermont’s honor. He advised King John to attack the English immediately. He went so far as to say he was going to charge the enemy regardless. At that point, Clermont reluctantly agreed to join the planned attack.

At mid-morning the French vanguard began its attack. Audrehem directed his company against the positions held by the earls of Warwick and Oxford. In his wake marched the dismounted men-at-arms led by the Constable of France and Lord Douglas. Clermont began his assault shortly afterwards. Since Audrehem was farther away from the English than Clermont, the result was that both French mounted companies struck the English position at the same time. As the mounted nobles thundered across the land between the armies, the English archers on both flanks opened fire. To their dismay, the plate armor of both the French knights and their horses rendered their arrows ineffective.

Upon hearing the sounds of battle, Warwick and his men began returning. In his absence, Oxford made the timely decision to have his archers push forward, probably using the marshy terrain as a natural barrier, to get into a position to fire into the unprotected flanks and rear of the war mounts. The tactic succeeded as horses began to falter when the arrows struck home. These horses, with or without riders, caused some disruption among the dismounted French men-at-arms following the mounted charge. Nevertheless, the troops under Lord Douglas and the Constable of France succeeded in reaching the hedgerow.

Although his force was a shorter distance from Salisbury’s line, Clermont was unable to take a direct route; instead, he had to move around more vineyards and thorn bushes than Audrehem’s men. His men were forced to narrow their attack front upon reaching the hedgerow gap. Some attackers penetrated the large gap. At some point, the supporting crossbowmen arrived and tried to put down suppressing fire. Salisbury counterattacked. His troops slaughtered those French men-at-arms inside the English position and hurled back the enemy.

Audrehem’s attack also proved ineffective. The French vanguard had suffered horrific casualties in exchange for creating a few additional gaps in the English line for the next French division. Marshal Clermont and Constable de Brienne lay dead on the battlefield. While a wounded Lord Douglas escaped, the English captured Marshal Audrehem.

As the battered remnants of the French vanguard made their way back, the second division marched forward. Any chance of a concentrated assault evaporated when members of the vanguard collided with part of the dauphin’s division. The scope of the vanguard’s defeat may have been unrealized as some of the first wave’s men still battled at the hedgerow. Instead of targeting the flanks, the dauphin attacked the English defenses just right of center, Prince Edward’s sector. The 4,000 French men-at-arms began to tire after crossing the open field being showered by arrows, with the last stretch uphill through vines and thickets.

The sanguinary clash of arms at Poitiers lasted nearly four hours, which was longer than most battles of the period. The dauphin’s division and its Anglo-Gascon foe slugged it out for two hours with no quarter asked for and none given. As swords clashed or met shields, casualties mounted for both sides. The French men-at-arms made their way through minor gaps or hacked through hedgerows to create new ones. At one point in the battle, the French breached the Anglo-Gascon defense, yet Edward still did not commit his reserve.

The earls of Salisbury and Suffolk moved among their men redirecting the archers and raising the morale of their troops. They drove back the French. It was during this phase of the battle that the Duc de Bourbon was slain. The dauphin’s guardians removed him from the battlefield for his safety. His brothers Louis and John also were escorted off the field in the direction of Chauvigny.

For reasons that are unclear, the Duc d’Orleans, also withdrew to Chauvigny. He claimed that he did so under orders from the king, but few believed the claim. Of his 3,200 men, just short of one-half followed him. A small number carried on, resulting in a feeble attempt easily repulsed. Those who either did not follow the Duc d’Orleans or attack joined the king’s division. Edward’s battle-weary men took advantage of the brief lull to take a moment to rest. During this time they moved their wounded to the rear and scavenged the battlefield for intact French weapons and usable arrows. Edward knew that he had to maintain a reserve to counter the attack of King John’s men, so he reorganized his men into one large group. He also instructed Captal de Buch to pick 60 mounted knights and 100 mounted archers, swing around the French flank, and attack the enemy from the rear.

About midday, King John ordered the division forward. Absorbing survivors from the first two assaults and men from his brother’s division, the force swelled to 4,000 men-at-arms and 300 crossbowmen. John instructed Charny to raise France’s sacred banner, the blood-red Oriflamme.

He also issued orders that the French were not to take prisoners. As the French marched forward behind a wall of shields, the Genoese crossbowmen maintained a steady fire. The English archers had a limited ability to respond given that they were saving their few remaining arrows.

The sight of a fourth French attack force with the unfurled Oriflamme demoralized the exhausted Anglo-Gascon soldiers. Morale dropped further at the sight of the Captal de Buch and his force riding away, as not all had not been informed of the flanking tactic. Seeing his men’s confidence start to waver, Prince Edward issued orders for an advance to meet the French. The strength of the English counterattack was Edward’s reserve of 400 men-at-arms.

The Captal de Buch’s mounted force forded the River Miosson at the Gue de l’Homme and re-crossed at the Gue de Russon ford. Using a hill as a screen, the strike force arrived behind the French king. Once in position, the St. George standard was raised for Edward to see. Captal de Buch spurred his men into action and charged into the unsuspecting French.

At the same time, Prince Edward ordered a forward advance. Salisbury’s troops struck King John’s men head-on, while Warwick’s men crashed into the French right flank. After expending all their arrows, the English archers exchanged their bows for swords, axes, and clubs and joined the melee.

Even though the fourth French division contained most of the best knights in France, the abrupt shock of the unexpected charge into their rear broke their morale and cohesiveness. In contrast to the exhausting slugfest when Dauphin Charles fought, this phase of the battle went quickly. Many Frenchmen fled either trying to escape across the Miosson or by running five miles to Poitiers. The English pursued the retreating French to the gates of the city. Seeing the English approaching behind them, the citizens of the town refused to open the gates. The English proceeded to slaughter the French men-at-arms.

A small pocket of French troops stubbornly fought on. They soon found themselves pushed into a loop of the Miosson that became known as the Champ d’Alexandre. The crack troops of the Order of the Star continued protecting their nobles. Both sides took note when the Oriflamme fell to the ground, its standard bearer slain. Swinging his battle axe, King John outfought those who engaged him in single combat, although these souls were unaware of whom they fought. Not until Denis de Morbecque discerned his identity and negotiated the French king’s surrender was the truth revealed. With the capture of the king, the battle essentially ended. “Never before had there been so disastrous a rout,” wrote chronicler John Froissart of the French defeat.

The Black Prince dined later that evening with the French king in his tent. The Anglo-Gascon army stayed in the vicinity of the battlefield until September 22. Ten days later the Black Prince’s army arrived in Gascony with its prisoners and precious loot.

The French suffered 2,500 killed and 2,600 captured, compared to 1,000 English killed. The French dead included the Duc de Bourbon, the Constable of France, and Marshal Clermont. Among the 42 French nobles taken captive were King John, Prince Phillippe, and Marshal Audrehem. For capturing the French monarch, Morbecque received a lifelong pension from King Edward III.

For a number of months, lack of effective central government brought about a situation close to anarchy in France. Dauphin Charles was proclaimed regent in March 1358 as his father remained a prisoner indefinitely in England. Four years after the battle the two sides signed the Treaty of Bretigny. The terms of the treaty dictated that the French had to cede large swaths of southwestern France to England. Moreover, the French would have to pay the English crown three million gold ecu for King John’s freedom.

King John reigned until his death in 1364 at which time the dauphin took the throne as King Charles V. Expected to follow his father as the next king of England, the Black Prince continued fighting the French in Spain and defending Aquitaine. He died on June 8, 1376, nine months before his father. Edward III was succeeded by Richard of Bourdeaux, the Black Prince’s son, who became King Richard II.

At Poitiers, Edward had been able to force the French to fight on terrain of his choosing, and his army had received their attack in a strong defensive position. Under his capable leadership, the Anglo-Gascon troops marched and fought together for another year. For his part, King John had failed at Poitiers largely because of an inability to foster close cooperation among French units on the battlefield. In all the battles between England and France, the clash at Poitiers is remembered as the one in which the French king became prisoner of England.

Although the English would prevail in several famous battles, most notably at Agincourt in 1415, the tide of war gradually shifted to the French in the aftermath of the successful relief of the besieged city of Orleans on the Loire River in north-central France in 1429. Two French victories, at Formigny in 1450 and Castillon in 1453, capped the French counteroffensive. Although the clash at Castillon is considered the last battle of the Hundred Years’ War, England and France remained at war for another 20 years. The instability of the English throne, though, meant that the English were no longer able to defend their claims in France, and they lost all of their territory except for the port of Calais. France finally retook Calais, the last continental possession of England, on January 7, 1558, in another war between the two crowns.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments