By Kelly Bell

On February 3, 1943, Lieutenant Herbert Kuntz of the 100th Bomber Group made the last flight by any German pilot over the Soviet city of Stalingrad. He circled at 6,000 feet in blinding fog and then descended until the ceiling fell away at just 200 feet. His Heinkel He-111 bomber was skimming over a combat-ravaged landscape, seemingly devoid of life.

Suddenly, Kuntz thought he saw men below but could not tell whether they were friend or foe. Nevertheless, he gave the order, “Load away!” The twin-engine bomber was carrying bread. The loaves spilled from the bomb bay doors and into the freezing tempest, almost certainly never to be found. His mission accomplished, Kuntz turned his plane westward. Stalingrad had seen the last of the Luftwaffe.

In millions of minds, “Stalingrad” is synonymous with the turning point of World War II in Europe. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called it “the end of the beginning,” in this case of a global conflagration whose first three years had generally been dominated by the criminal Axis powers. The reasons for the Red Army’s triumph at Stalingrad are numerous, but the air forces of both sides played key, ofter underappreciated roles.

Hitler’s predilection for overwhelming air power was the soul of his success in overrunning western and southern Europe and a gargantuan expanse of Soviet Russia. Air power had emerged as the dominant factor in a new era of warfare in which the heavens had become battlefields and the abode of terrifying machines. By 1942, aerial warfare was having an infinitely greater impact than thought possible a short time before. For the first time in history, entire cities could be devastated by warplanes. Nowhere was the power of air forces more evident than on the Russian front.

The titanic invasion of the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa, had seen his air arm, the Luftwaffe, used mainly as a “fire fighting” instrument. Air units were rushed to various sectors to assist foundering ground forces. Such situations multiplied as 1941 waned and Russian resistance stiffened. Airborne firepower was a major factor in saving the front from collapsing late in the year.

By April 1942, Hitler expected his airmen to support infantry and armored formations, as well as target Russian railways and storage facilities behind the front. Warplanes also would provide a protective umbrella against the steadily swelling formations of the Red Air Force (the Voyenno-vozdushnyye sily, or VVS.)

The Luftwaffe’s senior commander in Russia, General Wolfram von Richthofen, was well qualified to direct aerial operations, but felt stifled by the unavoidable restrictions and responsibilities that came with his fleet’s new dedication to low-altitude close support. To him, the air force seemed totally at the beck and call of the army. Still, von Richthofen, who took over his post in southern Russia in April 1942, performed his new duties brilliantly. In the end, however, it would not be enough.

The Holy Grail for Germany in the spring and summer of 1942 was Soviet oil. The Third Reich had few sources of this lifeblood other than the fields in Romania, and those fields were insufficient to adequately support the rampaging Wehrmacht. The Soviet Union’s heavily industrialized Caucasus region harbored one of the richest sources of crude oil on earth in the state of Azerbaijan. The province’s capital city of Baku alone produced 24 million tons of oil in 1942.

While Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, who erroneously believed the Nazis would attempt to repeat the previous year’s drive on Moscow, was massing the bulk of his forces to oppose an offensive that would never come, Hitler was planning to lunge for the Caucasus far to the south. The industrial city of Stalingrad was in the path of the Wehrmacht’s coming thrust.

Hitler did not initially consider the outright capture of Stalingrad a necessity. He figured his aims could be accomplished simply by razing the city to the point that the Red Army could not use it as a staging point for counterattacks on German forces. Situated on the deep and busy Volga River, Stalingrad would also be an ideal base for supply and reinforcement convoys. Its usefulness as an armament-producing and transportation center made its destruction essential.

Although von Richthofen’s Fliegerkorps IV struck at Stalingrad as early as April, bombing a tractor works and gun factory in three heavy nocturnal raids, most of the Wehrmacht’s efforts in the summer of 1942 were devoted to the bloody conquest of the huge Crimean peninsula. By the time the Germans were able to turn to their Führer’s overall objective, the summer was waning, but there was still plenty of time to commence the most important battle of World War II.

Late in July, the German Sixth and Fourth Panzer Armies were bearing down on Stalingrad. Hitler, however, was worried about Soviet General Rodion Malinovskii’s Southern Front in the central Don River area. To ensure that Malinovskii could not interfere with the drive on Baku, the Führer detached the Fourth Panzer Army southward. He also took most of Sixth Army’s armor and gave it to the First Panzer Army for its assault on Rostov. On July 20, 1942, Hitler ordered the Sixth Army, alone and virtually without armor, to attack and secure Stalingrad. Paulus and his troops were dangerously overconfident. With the bulk of the Red Army still clustered uselessly around distant Moscow, the early stages of the German advance had been deceptively easy, but opposition was already beginning to mount.

The air unit most involved in supporting Paulus at this point was Fliegerkorps VIII, commanded by General Martin Fiebig, whose specialty was close air support. By this time, von Richthofen ordered Fiebig to direct his command’s efforts against the city and the increasingly stubborn defenses along its approaches. Richthofen also transferred General Kurt Pflugbeil’s Fliegerkorps IV from the Caucasus to assist in the investment of Stalingrad and to deliver supplies to German ground forces. On August 19, von Richthofen noted in his diary, “The enemy there is increasingly stronger and fights with more determination.”

On the morning of August 7, the Sixth Army’s 14th and 24th Panzer Corps, beneath massed formations of Pflugbeil’s and Fiebig’s aircraft, had cut from north and south into the base of a salient protruding westward from the town of Kalach, linking up and trapping the Soviet 62nd Army. The 51st Army Corps rushed to help the two Panzer corps crush Russian resistance within the huge pocket, killing a massive number of Red Army soldiers while capturing 50,000 prisoners and 1,100 tanks.

The Red Air Force did its best, but the planes available to it throughout this period were no matches for the Luftwaffe’s. Germany’s Eastern air fleet was still technologically and numerically superior to the Soviet 8th Air Army, which was all that was available in the Stalingrad sector. Although 447 VVS warplanes were delivered between July 20 and August 17, few lasted long. On August 12, a formation of 26 Soviet planes attacked German airfields. Interceptors shot down 25. The following day 45 VVS planes tried to disable the lethal Nazi air bases. The Germans shot down 35 of these. In neither attack did the Luftwaffe lose a single plane. With the threat of the 62nd Army gone and the skies above him dominated by German aircraft, Paulus continued toward Stalingrad.

By August 18, the Sixth Army had bridged the Don River at several points, establishing a bridgehead 35 kilometers long. On August 21, Paulus sent his 51st Army Corps on a surprise attack on Vertyachiy. Astonished by this aggressive assault ordered by a general they had been told was timid and hesitant, the Soviets collapsed and fled eastward in disorder. Throughout their flight, the Soviets were subjected to murderous strafing by Fliegerkorps VIII. Later that afternoon von Richthofen personally flew his Fieseler Storch reconnaissance plane over the bend of the River Don north of Kalach and was stunned by the “extraordinarily many knocked-out tanks and dead.”

Before dusk, Junkers Ju-88 bombers wiped out two Soviet reserve divisions caught on open ground 150 kilometers east of Stalingrad. By 4 pm on that eventful day, the 14th Panzer Corps, following flocks of bombers from Fliegerkorps IV and VIII, rumbled into Stalingrad’s northern suburbs. The day was still not over.

Just after von Richthofen’s observation flight, Fiebig launched a major attack on the city itself. Waves of twin-engine bombers commenced a three-day orgy of destruction, unloading an almost continuous shower of high explosives. Stalingrad was not well prepared for air attackers. Antiaircraft batteries and air raid shelters were few. The 900 tons of bombs dropped by Fieberg’s aircrews killed an estimated 40,000 civilians. Hits on oil storage tanks and tankers docked on the Volga coated the river with a blazing black sheen that temporarily stopped the flow of supplies and reinforcements.

However, this spectacular destruction did little for Nazi ground forces. Lt. Gen. Hans Hube’s 16th Panzer Division entered the northern suburb of Rynok but quickly bogged down before stubborn opposition from the Red Army and armed civilians. Using rubble as defensive emplacements, these resolute, bereaved defenders, virtually all of them mourning the loss of loved ones to German bombs, refused to let the panzers enter the adjacent Spartakovka industrial district.

On August 29, in spite of their differences, the service branches cooperated brilliantly as powerful air units paved the way for General Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army, which charged from the southwest and drove all the way to the Volga to bolster Hube’s bogged down troops. Prudently abandoning their positions before they could be surrounded, the Russian 62nd and 64th Armies fell back into the suburbs and hastily set up defenses.

Believing the city’s fall imminent, von Richthofen ordered a fresh round of intensive bombing raids. Using every airplane at his disposal, Fiebig commenced a 24-hour terror attack on Stalingrad September 3, destroying the rubble from the earlier bombings, obliterating 62nd Army’s command center, and leveling several VVS airfields east of the Volga.

By this point, General Georgi Zhukov, recently promoted to Soviet deputy supreme commander, had taken over Stalingrad’s defense. Eager to dissipate the growing German momentum, he launched a large counteroffensive from north of the city at dawn on September 5. Despite grievous losses inflicted by the swarming Luftwaffe, the Soviet 1st Guards and the 24th and 66th Armies ground forward for five days, heartened by the steadily increasing number of their own aircraft coming to their support. The planes were from the understrength but game 8th and 16th Air Armies and Lt. Gen. Golanov’s long-range bombing group. Still, Hoth’s tanks managed to cut a corridor between the 62nd and 64th Armies on September 10. Three days later, German troops finally managed to leave the suburbs, enter Stalingrad itself, and commence clearing streets of defenders.

By this point, virtually round-the-clock combat activity was significantly cutting into German air strength. By September 20, Luftflotte IV, reduced to just 129 airworthy planes, found itself increasingly on the defensive. At the same time, the strength of the VVS was waxing.

The Soviets had noted the German aversion to night fighting. The Luftwaffe lacked the specialized navigation and bomb-aiming equipment for nocturnal warfare, so the Red Army defenders began to step up night action, when they need not fear interference from enemy aircraft. As General Vasili Chuikov later noted, “The enemy could not fight at night, but we learned to do so out of bitter necessity.”

Russian fighting strength within the city was maintained by a small but steady flow of supplies and reinforcements from the east bank of the Volga despite constant losses to air attacks. Yet even in daylight this lifeline began making increased deliveries because of the attrition of local Luftwaffe units. By month’s end, von Richthofen’s air fleet had fallen to just 396 operational combat planes, a little more than one third of its original strength, and the bulk of these were occupied with ground support, leaving few craft available to assail the Volga supply pipeline. Also, the small size of the ferries and barges carrying men and materiel across the river made them difficult targets, and many bombs and bullets splashed harmlessly into empty water.

The defenders even managed to construct a couple of 300-yard footbridges on floating barrels lashed together with ropes. Because these slender avenues proved virtually impossible for Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers to hit, thousands of Soviet reinforcements used them to cross the river. Furthermore, Red Army antiaircraft units in and around Stalingrad were significantly strengthened in October, providing yet another hazard to von Richthofen’s dwindling air arm. The Luftwaffe was severely overtaxed along the massive length of the Russian front, and few reserves were available.

On September 26, despite growing resistance and diminishing air support, Paulus reported to Berlin that the heart of Stalingrad was firmly in German hands. It was, but his report made the situation sound much more promising than it was in reality. The weather was also getting colder.

Kampfgruppe 55’s meteorologist, Friedrich Wobst, later described how “a fine summer and autumn were behind us, and the Luftwaffe was in control of the region. Hence we viewed with anxiety the inevitable season of bad weather—the Russians’ best ally because it would tie the Luftwaffe’s hands.”

The pilots of the proliferating VVS fighter squadrons fought as fanatically as did their brethren on the ground, hurling themselves with utter abandon into German bomber formations. When their ammunition ran out, Soviet pilots would often ram German planes, sacrificing themselves to eliminate just one more of the hated Stukas. Still, for now, the Luftwaffe remained in general control of the airspace above Stalingrad.

On September 27, Chuikov appealed directly to the region’s political commissar, future Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, for increased air support, noting that the problem with the VVS was not its quality, but its still relatively small numbers. Khrushchev replied that Moscow was already giving the Stalingrad sector all it could but promised to “press for increased air cover for the city.”

On October 1, Luftwaffe planes and 88mm flak guns hurled back a major Soviet offensive north of Stalingrad, destroying 60 tanks and downing 18 VVS planes with no air losses of their own. Heartened by this success, Fiebig launched a heavy raid on oil storage facilities near the Red October factory the following day. Chuikov had thought the immense petroleum tanks were empty, but when hit by bombs they exploded like volcanoes, inundating nearby Soviet positions in blazing oil. Reaching the Volga, the burning crude spread across its surface, immolating barges, ferries, and anything else combustible. Despite such spectacular air assaults, German ground troops continued to advance at a glacial pace.

On October 12 and 13, many of Fiebig’s units returned from temporary assignment in the Caucasus. German ground forces had spent the past week regrouping, fending off minor counterassaults, and absorbing meager reinforcements. On the 14th, the Germans made their last major effort to secure the rest of Stalingrad, hurling the 14th Panzer Division, the 305th and 389th Infantry Divisions, and some assorted smaller units against the remnants of the 62nd Army holding the Dzerzhinski tractor factory and the surrounding industrial district.

Following bombers that unloaded 600 tons of high explosives on the defenders, almost 200 tanks ground into the twisted but easily defended detritus harboring an army of desperate men and women determined to die rather than let the Nazis pass. The Soviets were stunned by what Chuikov later called the attack’s “unprecedented ferocity.” A major factor in motivating the Germans to fight with such reckless abandon was their frantic desire to secure the city before the onset of the dreaded Russian winter.

The determination of the defenders, however, was stronger. After digging deep into the ruins, they emerged following the hellish bombing in numbers that surprised the invaders, closing with the Germans in fighting of surreal violence. Although the besiegers were still gaining ground, they were also running out of steam. By the end of October, the attack had been going on two weeks rather than the two or three days Paulus had envisioned. The Russians were proving themselves superior to the Germans in urban fighting, and as winter closed in the Red Army was coiling to strike back.

During the first week of November, German pilots began reporting an apparent buildup of hostile forces north and south of Stalingrad. On November 19, which dawned with a howling blizzard, more than 3,500 artillery pieces and mortars cut loose on the Romanian 3rd Army. One hour later, waves of screaming Soviet infantrymen clad in ghostly white winter camouflage broke over the shocked, decimated Romanians.

Largely the brainchild of Zhukov, the Soviet autumn counteroffensive had been in the works since early September. The Russian high command had kept feeding Chuikov, who for security’s sake was not privy to the pending operation, just enough reserves to keep him hanging on and convince the Germans that victory was imminent. This kept Paulus distracted from his vulnerable flanks while Zhukov built up his units facing what he called his enemy’s “satellite forces.” He considered these Hungarian, Romanian, and Italian troops less experienced and less motivated than the veteran German forces.

By November 19, the Soviets had delivered and deployed more than a million men, 13,540 mortars and artillery pieces, 894 tanks, and 1,115 priceless, state-of-the-art warplanes. Sweeping from north and south to link up in the German rear, the counteroffensive, code-named Operation Uranus, could not be stopped.

German aerial opposition was negligible during the battle’s crucial first days because of atrocious weather, and on the evening of November 23 two massive Russian pincers joined up outside the appropriately named town of Sovietskii. Virtually the entire German Sixth Army was encircled. More than 250,000 troops, about 100 tanks, nearly 2,000 heavy guns, and 10,000 assorted vehicles were trapped in a pocket just 40 kilometers from north to south and 50 kilometers from west to east.

Luftwaffe Chief of Staff General Hans Jeschonnek wasted no time rushing to Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia to discuss the new situation in the east, arriving that same day. Jeschonnek, possibly sensing his Führer was hoping for good news, rashly assured his chief that the Luftwaffe would keep the Sixth Army supplied until its encirclement could be broken.

Jeschonnek based his promise on the fact that his aircraft had successfully sustained about 100,000 troops temporarily surrounded in and around the city of Demyansk the previous winter. The chief of staff should have realized that this comparison was unrealistic. The soldiers in the Demyansk pocket, the 2nd Army Corps, had been less than half the number now trapped at Stalingrad. Also, there had been virtually no VVS presence over Demyansk to interfere with the delivery of the approximately 300 tons of supplies required daily by the German forces there, enabling the Luftwaffe easily to deliver the required tonnage until 2nd Army Corps could be rescued. Lastly, Germany had many more aircraft available in late 1941 than in late 1942.

The 250,000 Wehrmacht troops in the Stalingrad pocket would require a bare minimum of 750 tons of supplies daily—an impossible amount for the depleted German transport and bomber fleets to deliver. By the time of Zhukov’s huge counterattack, the Red Air Force was out in great numbers over the battlefront, presenting an aerial barrier to the proposed airlift. All this was much more evident to the men at the front than to their faraway Führer, who eagerly placed great faith in Jeschonnek’s foolish assurances. Hitler emphatically forbade Paulus to attempt to break out to the west (an operation for which he lacked sufficient fuel anyway) and instructed him to await his coming manna from heaven.

By the time Göring finally became involved, it was November 27, and the trapped troops of the Sixth Army were fighting for their lives and exhausting their supplies. “Göring,” asked the Führer, “can you keep the Sixth Army supplied by air?” Raising his right hand, the corpulent air chief replied, “Mein Führer, I assure you that the Luftwaffe can keep the Sixth Army supplied.”

General Kurt Zeitzler, chief of the general staff, however, had made detailed calculations on the proposed airlift’s requirements based on the number of men to be supported, the number of suitable aircraft available, their fuel requirements, and allowing for interference from the VVS and immoderate Russian weather. Zeitzler’s figures indicated that in favorable weather aircraft would have to ferry a minimum of 500 tons of supplies daily. “I can do that!” stammered Göring. “Mein Führer,” yelled Zeitzler, “That is a lie!”

For perhaps a minute Hitler silently pondered everything his bickering commanders had just told him. Finally he mildly replied, “The Reichsmarschal has made his report to me, which I have no choice but to believe. I therefore abide by my original decision [to support Sixth Army by air].” This meeting was the last realistic chance to save Paulus and his troops. Had the available aircraft been used solely to fly in fuel and ammunition, the Sixth Army might still have been able to break out of the city with air support and a counterthrust by German forces to the west.

Ordered to stand fast, a quarter million men would soon be too weakened and decimated by the Red Army, hunger, and numbing cold to break out even had they been permitted to try. Göring, meanwhile, did not deign to assist in the coming airlift’s planning and execution. Instead, he boarded his luxurious private train, Asia, and set out for a lengthy shopping spree in Paris.

Because of the demand for transport aircraft to supply Wehrmacht forces in North Africa, the bulk of the aircrews and planes diverted to the Stalingrad sector had to come from the Luftwaffe’s training programs. Trainers and instructors were soon en route to southern Russia, shutting down teaching facilities that provided sorely needed replacements for lost aircrews.

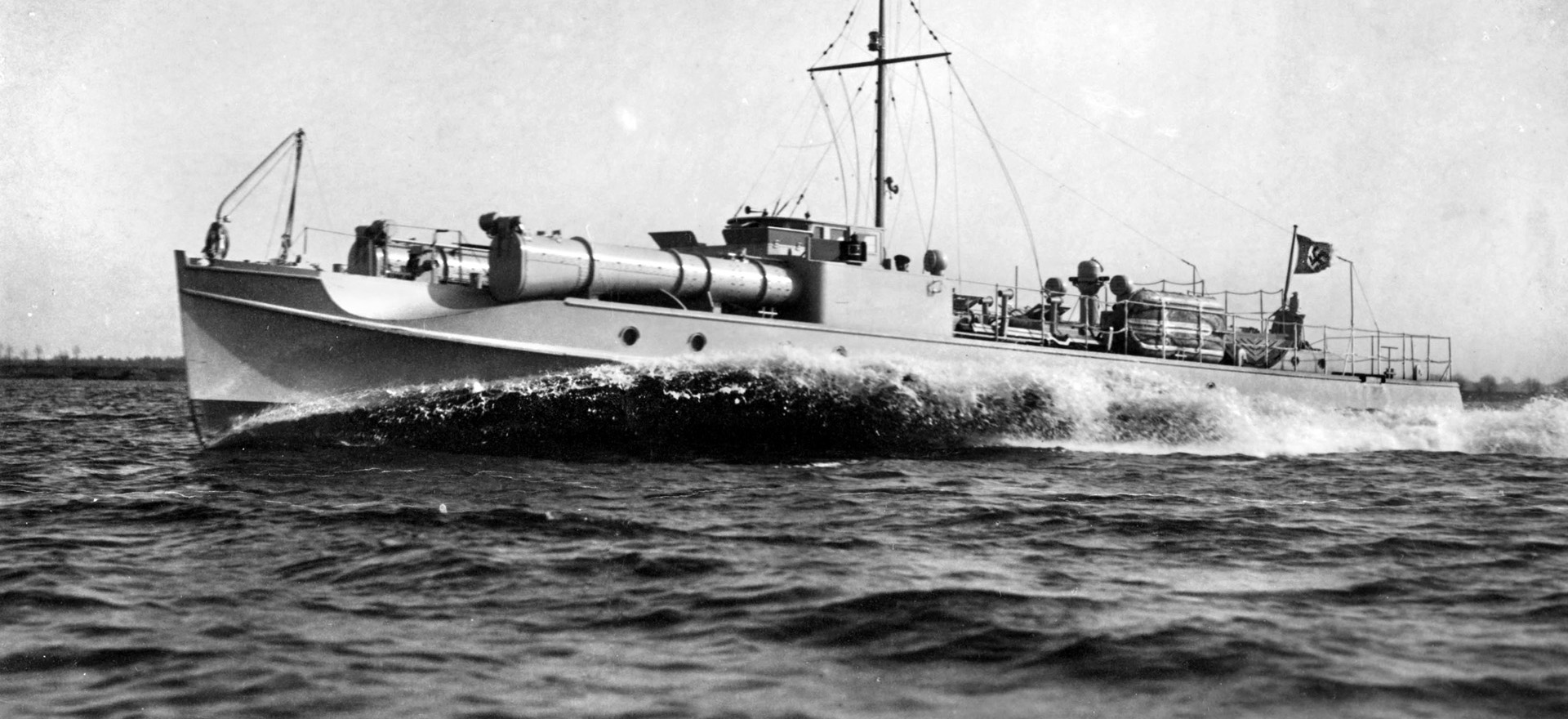

By the first week in December, the aircraft had been delivered. Most were the reliable Junkers Ju-52s, but there were also Heinkel He-111s, Junkers Ju-86s, Heinkel He-177s, Focke-Wulf FW-200s, Junkers Ju-90s, and Junkers Ju-290s. It all amounted to the impressive sounding total of 500 planes, but this was still far too few to ferry the required 300 tons a day. Also, many of these aircraft had not been designed to transport cargo; they were very unwieldy to load and unload as well as being prone to mechanical problems in the brutal winter of the Russian front.

When Luftwaffe squadrons had been forced to evacuate many of their airfields ahead of Zhukov’s November counteroffensive, the Soviet advance had been so swift that the Germans had not had time to adequately pack. They left behind a great number of snowplows and heating devices for thawing cold aircraft engines. As the airlift got underway, Fiebig had just 90 serviceable fighters, far too few to escort the transports, which soon began suffering losses to VVS fighters. Even so, crashes during takeoffs and landings on perpetually blizzard- swept runways would destroy more cargo planes than the Red Air Force. Through the first half of December, the Sixth Army received less than 20 percent of its minimum daily needs.

Finally recognizing the hopelessness of the situation in what he was calling “Fortress Stalingrad,” Hitler authorized Hoth to launch a rescue mission on December 12 with his 6th and 23rd Panzer Divisions from Kotelnikovo, 110 kilometers from Stalingrad. Followed by rifle regiments and antitank units, the expedition’s 230 white-painted tanks made fair initial progress. Soviet units in the path of Hoth’s advance were taken by surprise in the sudden assault.

Recognizing the danger, General Alex-andr Vasilevskii managed to convince Stalin to release the crack 2nd Guards Army from its position on the Don front so that it could block Hoth’s path. With air activity on both sides severely curtailed by weather, Hoth clawed forward through stiffening resistance for a week, reaching the Mishkova River 50 kilometers from the pocket. At this point the would-be rescuers were halted by powerful tank formations from the 2nd Guards.

General Erich von Manstein, now in overall command, radioed Berlin that the only way to save the Sixth Army was for it to break out and link up with Hoth’s stalled divisions. Hitler abruptly decided he was unwilling to abandon Stalingrad after all. Instead, he instructed Paulus to open a corridor to Hoth so that fuel, ammunition, reinforcements, and supplies could be delivered overland to enable the Sixth Army to hold the city. This would require the Luftwaffe to deliver the impossible amount of 4,000 tons of fuel to the trapped troops.

While Fiebig’s airmen tried vainly to meet Hitler’s demands, the Russians assaulted Hoth’s spearhead, driving him back from the Mishkova on Christmas Day. As the rescue offensive lost steam, a sense of hopelessness settled in throughout the pocket as aircraft were only able to fly in a meager 129 tons of supplies daily.

The Red Army had assembled a powerful curtain of flak around the German enclave, with the main concentration clustered under the airlift’s flight paths. Between these antiaircraft batteries, VVS fighters, and hostile weather, Fiebig lost 62 of his precious Junkers Ju-52s from December 28 to January 4.

By mid-January Soviet ground forces had captured Pitomnik, Tatsinskaya, and Morozovskaya airfields, the main landing strips inside the pocket. Their loss essentially ended the airlift as a viable operation. Even before these fields were overrun, Fiebig’s dwindling air fleet had managed to fly in an average of only 145 tons per day.

On January 14, Hitler ordered Field Marshal Erhard Milch, deputy supreme commander of the Luftwaffe and its air inspector general, to take over administration of the airlift. Milch tried hard at his impossible task, but on the morning of the 17th, as he was being driven to inspect Taganrog airstrip, a train appeared out of a thick fog bank at a crossing and broadsided his staff car. Milch’s two bodyguards were killed instantly while he suffered a severe head wound, major back injuries, and several broken ribs. He regained consciousness encased in plaster and gauze. Ignoring his injuries, high fever, and doctor’s orders, Milch immediately left the field hospital where he had been rushed and returned to his duties.

Milch did all he could, even experimenting with using gliders to deliver supplies, but nothing could break the vengeful Red Army’s stranglehold on the shrinking Stalingrad perimeter. On January 24, Paulus sent the high command this despondent message: “Troops without ammunition and food. Collapse inevitable. Army requests immediate permission to surrender in order to save the lives of remaining troops.” Hitler typically refused.

At 6:15 on the morning of January 31, the Sixth Army’s radio operator transmitted from its command post in the cellar of a destroyed department store: “Russians at the door. We are preparing to destroy [the radio equipment].” An hour later, Paulus sent his final message: “We are destroying [the equipment].” Just before noon, Paulus, obeying his Führer’s orders to not surrender his army, surrendered only himself and what was left of his staff. The previous day Hitler had promoted him to field marshal. He was the first German field marshal ever to surrender to an enemy. Over the next three days, the last Nazi holdouts in the city laid down their arms.

From the airlift’s inception on November 24, 1942, until February 2, 1943, German planes delivered only about 8,350 tons of supplies to the encircled troops. They flew out 30,000 sick and wounded soldiers. The VVS and inclement weather accounted for 166 German aircraft lost, 108 missing, and 214 damaged beyond repair. It was the equivalent of more than one full air corps. About 1,000 of the Luftwaffe’s finest pilots, aircrew, and instructors had been killed or captured.

Hitler’s 1942 summer offensive was Germany’s greatest military undertaking of World War II. Mainly through the efforts of his air force, he nearly achieved his quest. Now, though, the Third Reich was mortally wounded.

Hitler’s late July decision to deviate from the original plan to send nearly all available German forces directly for the oilfields of the Caucasus was critical. Encouraged by the crusade’s early successes, Hitler divided his forces and attempted to take the Caucasus and Stalingrad simultaneously, spreading his air and ground forces too thin. The oil metropolis of Baku alone, to which the panzers had come so tantalizingly close, continued to provide 80 percent of all Soviet petroleum production.

Von Richthofen, Milch, Fiebig, and their subordinates were among the most competent German commanders, but they could not overcome the fatal obstacle of inadequate resources. Even before Stalingrad fell, von Richthofen began reorganizing his air fleet for future tasks. These assignments would be almost exclusively defensive as the front commenced an inexorable westward movement.

Kelly Bell has been writing professionally about World War II for 17 years. Working from his home in Tyler, Texas, he has contributed to Command, World War II History, and Strategy & Tactics. He is a former newspaper staff writer.

Join The Conversation

Comments