By Arnold Blumberg

During the early afternoon of July 9, 1864, the 103rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment of Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield’s Army of the Ohio crossed a 300-yard stretch of shallow water on the Chattahoochee River in north-central Georgia. Confederate opposition to the passage consisted of a few dozen state militiamen supported by one outdated 6-pounder cannon. By nightfall, Federal troops had brushed aside the feeble enemy opposition, and the 12th Kentucky Volunteer Infantry Regiment had secured the beachhead the 103rd Ohio had established earlier in the day. With one audacious move, the Confederate position on the formidable Chattahoochee had been fatally compromised. The Federals found themselves only 12 miles from the center of Atlanta, the main objective of the campaign, with no major obstacles left in their path.

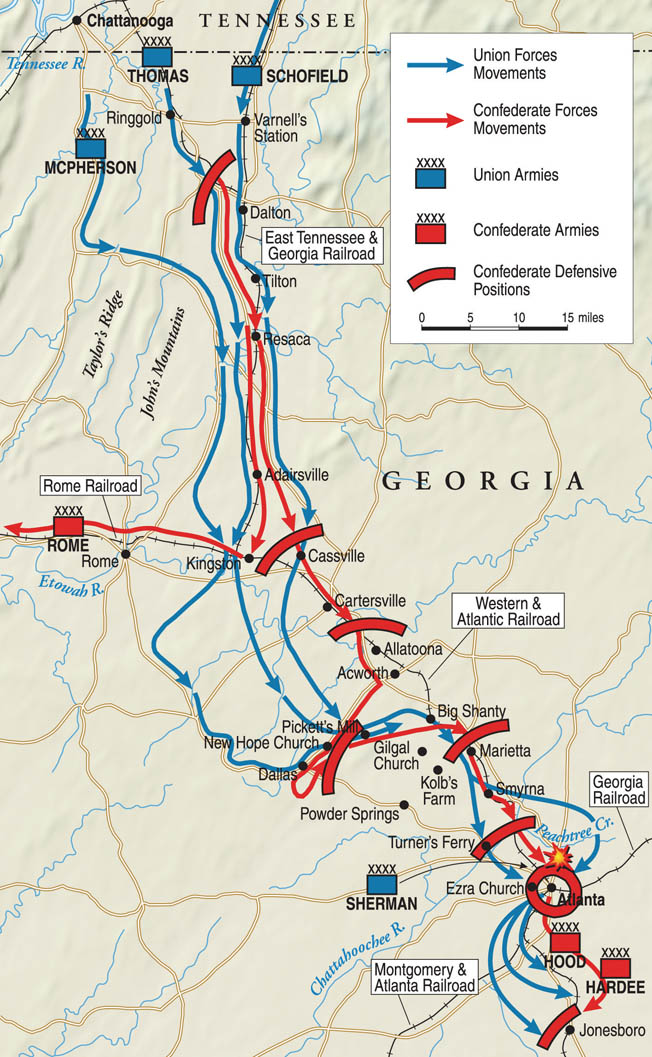

Learning that the enemy had outflanked him and had crossed to the south bank of the Chattahoochee, General Joseph E. Johnston, commander of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, ordered a retreat to the outer fortifications of Atlanta. This latest retrograde movement was the most recent, but scarcely the first, for the southern army since Federal forces under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman had initiated the Atlanta campaign in early May. The relentless advance of Sherman’s blue host had started in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and had carried them 100 miles to the outskirts of Atlanta. Along the way, the Federal juggernaut had clashed with Confederate forces at Resaca, Cassville, New Hope Church, Marietta, and Kennesaw Mountain. The result was always the same: Union turning movements, made possible by superior numbers and maneuverability, forced the graycoats to withdraw from one successive line to the next.

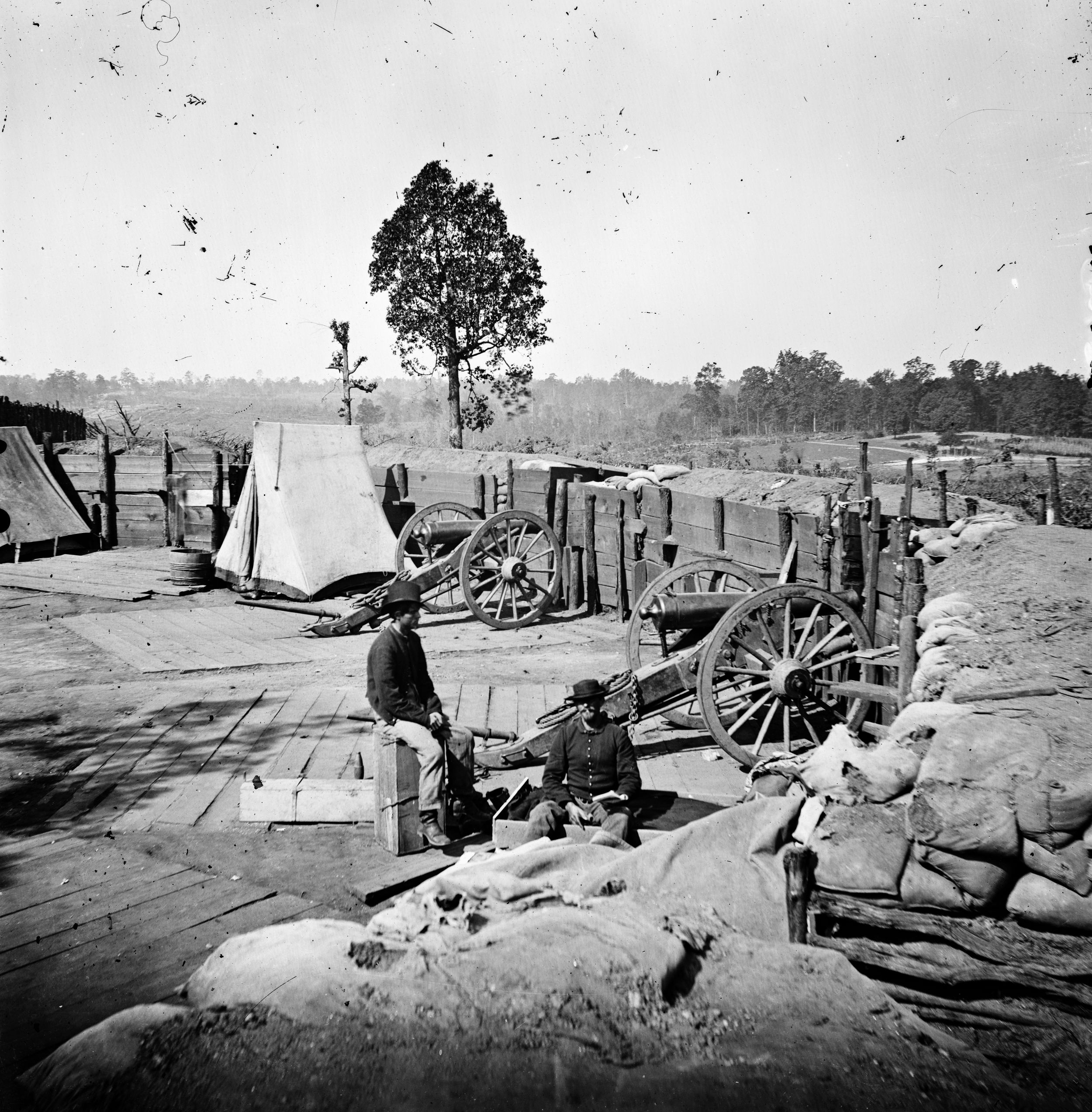

The fortifications surrounding Atlanta, begun the previous year under the supervision of chief engineer Captain Lemuel P. Grant, featured five large redoubts on the high ground around the city, all connected by a line of rifle pits. To create a good field of fire for the artillery, woods up to 1,000 yards in front of the batteries had been cut down. By the time of its completion, the defensive perimeter surrounding the city was 10 miles long and contained 19 gun positions holding 77 artillery pieces. The Confederate defenses also featured rows of sharp wooden palisades planted along the foot of the exterior slope of the infantry parapets at a height of 12 to 14 feet. A small force of determined defenders could easily hold off large numbers of attackers.

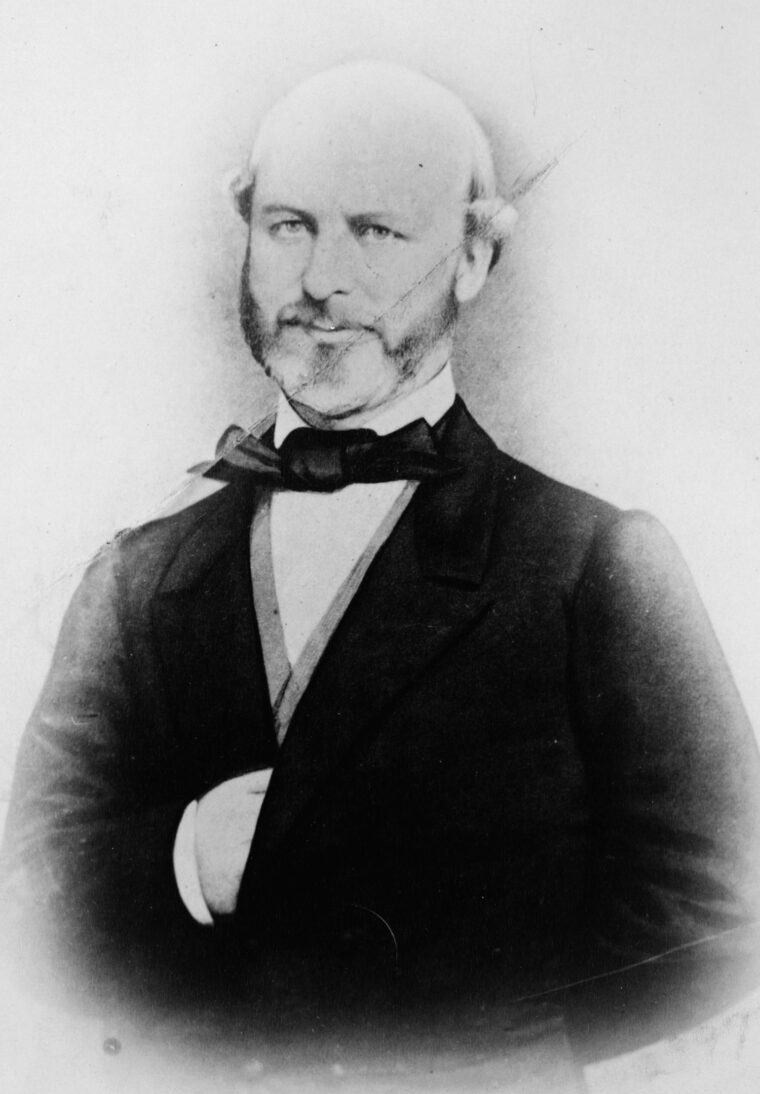

After retiring from the line of the Chattahoochee, Johnston placed his men in hastily dug works on high ground one mile south of Peachtree Creek, a main tributary of the river. The summer rains had filled the 40-foot-wide watercourse with about three feet of water, which in conjunction with its rock-strewn bottom made passage difficult and time-consuming. At this point, Johnston’s plan to hang onto the city hinged on his hope that the defensive strength of the town would deter a direct Federal attack. Johnston repeatedly warned that the numerical disparity between his army and his opponent was so great that it precluded any serious offensive move on his part. Appealing directly to Confederate President Jefferson Davis—no particular admirer—Johnston urged that cavalry units from Alabama or Mississippi be sent to disrupt the Federal rail line supplying Sherman’s men in northern Georgia. Davis thought the mounted force in Johnston’s own army, which was already on the scene, should carry out the raid. The general replied that he was so short of men that he could not possibly detach any riders for such a mission.

While Johnston hesitated, Davis fumed. The president had never believed the general’s assertion that he was hugely outnumbered by the Federals, and this suspicion was reinforced by reports he was receiving regularly from officers within Johnston’s army. Behind the general’s back, corps commanders William J. Hardee and John Bell Hood wrote to Davis’s chief military adviser and close friend, Braxton Bragg, complaining that Johnston had missed a number of opportunities to strike the enemy. “We should not, under any circumstances, allow the enemy to gain possession of Atlanta,” Hood told Bragg, adding with a typical flourish of self-promotion: “I have, General, so often urged that we should force the enemy to give us battle as to almost be regarded reckless by the officers high in rank in this army, since their views have been so directly opposite. I regard it as a great misfortune that we failed to give battle to the enemy many miles north of our present position. Please say to the President that I shall continue to do my duty cheerfully and faithfully.”

A particularly damaging statement came from the head of the army’s cavalry, Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, who insisted that he had suggested conducting the very type of mounted strike favored by Davis, but had been denied the opportunity by his commander. Georgia Senator Benjamin H. Hill also fumed over Johnston’s reluctance to attack. After returning to Atlanta from a visit with Davis in Richmond, the senator telegraphed the general that he must give battle immediately. “For God’s sake do it,” Hill implored. Johnston ignored him, informing Davis instead that he was waiting for an opportunity “to fight to advantage.” Somehow, such an opportunity never seemed to come.

Johnston Falls out of Favor

As the Federal troops under Sherman drew ever nearer to Atlanta, Davis wrestled with the idea of sacking Johnston. He hesitated only because he did not know who a proper replacement would be. To answer that question, he sent Bragg (the failed former commander of the western army) to Atlanta. Arriving on July 13, Bragg met with Johnston and the army’s senior officers. In a confidential telegram to Davis, Bragg complained that he had found “but little encouraging,” and could not puzzle out what Johnston intended to do to defend Atlanta. In a follow-up communication, Bragg suggested that John Bell Hood might be a good replacement for Johnston, adding that although Hood was an unknown quantity, he was still “far better in the present emergency than anyone we have available.” It was hardly a glowing endorsement.

Bemused by Bragg’s left-handed recommendation, Davis still hesitated to remove Johnston from command. He understood that Johnston was popular with his men for the way he looked after their daily welfare and refused to hazard their lives in risky frontal assaults. As a result, Johnston’s removal might plunge the army’s morale to an even lower depth than it already was in owing to its continuous retreats over the last 21/2 months. Furthermore, Davis feared that replacing Johnston in the midst of an ongoing campaign might throw the army’s command structure into dangerous disarray. Davis dithered over the issue for the next three days.

On July 16, Davis received a communication from Johnston outlining his plan of operation at Atlanta, as requested by Davis a few days earlier. The president was shocked and upset. Johnston’s message stated flatly that, because of the disparity in numbers between the opposing forces, the Confederates would have to continue their defensive strategy. To Davis, that meant the certain fall of Atlanta. As the site of one of the South’s few remaining manufacturing centers, the city was a vital transportation hub and the home of 22,000 loyal residents. Its loss would be incalculable to the Confederate war effort. Spurred by this somber thought, Davis removed Johnston the next day and placed Hood at the helm of the Army of Tennessee. On July 18, Hood was made a temporary full general in keeping with his new responsibilities.

The Untested John Bell Hood

A graduate of the United State Military Academy, Class of 1853, the 33-year-old Hood had made an impressive record with Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia as an audacious and gritty combat commander. He had been severely wounded in the arm at Gettysburg and had lost a leg while on detached duty at the Battle of Chickamauga. Promoted to lieutenant general in early 1864, Hood was assigned as a corps commander in the Army of Tennessee. Yet for all his valor on the battlefield, many in the army doubted Hood’s capacity for command beyond the division level. This opinion was shared by Lee. When Davis asked him if Hood should succeed Johnston, Lee replied honestly: “Hood is a bold fighter. I am doubtful as to the other qualities necessary.”

Lee went on to point out that his former subordinate, although gallant, zealous, and earnest, had never been tested with the complex responsibilities of army command. Lee concluded by suggesting that Hardee, the senior corps commander in the Army of Tennessee, be chosen as Johnston’s replacement instead. Davis, having already offered the post to Hardee after Bragg’s disastrous defeat at Missionary Ridge the previous November, had no intention of renewing his offer. He cared nothing for Hardee, either personally or politically. Hood, a personal friend and protégé of the president, was a better choice, Davis believed.

Others were not so sure. The reaction of the common soldiers upon hearing of Hood’s elevation was predictable—most were not pleased with the change. Maj. Gen. Arthur M. Manigault noted that “the army received the announcement with very bad grace, and with no little murmuring.” Others complained that Hood was a “dandy” from the privileged Army of Northern Virginia who did not fully understand the brutal fighting conditions in the western theater. The word “butcher” was used by many of the troops in describing the new leader’s preferred method of combat operations.

If the reaction within the Confederate army was one of consternation and doubt, the news of his assignment was met with rejoicing by the Federal officers gathered north of Atlanta. First becoming aware of the change from reading Atlanta newspapers, many officers on Sherman’s staff, who knew Hood from the Old Army, were pleased. Their overall opinion of their former comrade’s ability was low. Maj. Gen. George Thomas, one of Hood’s instructors at West Point, was not convinced. He warned Sherman that the rash Confederate would “hit you like hell before you know it.” Oliver O. Howard, a corps commander, chimed in that Hood was “a stupid fellow, but a hard fighter.” Sherman, far from being alarmed, welcomed the prospect. If Hood attacked the Union forces, which outnumbered him by more than two-to-one, it would give Sherman a chance to crush the Confederates in the open, away from their formidable fortifications outside Atlanta. In a letter to his wife, Ellen, Sherman mused on his good fortune, telling her that “at this critical moment the Confederate Government rendered us a most valuable service. I confess I was pleased with the change.”

The Opposing Forces

After crossing the Chattahoochee, Sherman moved his armies southeastward in a huge arc toward Decatur, where he planned to cut the railroad east of Atlanta. By July 17, Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland had moved to the north bank of the Chattahoochee; Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s 20,000-man Army of the Tennessee was 12 miles farther up the watercourse; and Schofield’s Army of the Ohio was on the eastern shore, halfway between the other two armies. By the 18th, Thomas had reached Peachtree Creek and driven off the enemy cavalry and infantry guarding its south bank. McPherson and Schofield arrived just north of Peachtree Creek later that day.

Farther to the east, Federal cavalry under Brig. Gen. Kenner Garrard, aided by an infantry brigade from the Army of the Tennessee, cut the Georgia Railroad 13 miles east of Atlanta. The city was slowly being isolated from the rest of the Confederacy. Sherman’s long-held strategy for taking the town was on course. After crossing the Chattahoochee, he would cut the railroad between Atlanta and Montgomery and then move on Atlanta from the left. Sherman’s armies fielded a total of 106,070 men, including 88,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry, and 6,000 artillery. He ordered Thomas to head toward Atlanta at dawn the next day. “With McPherson, Howard, and Schofield, I would have ample to fight the whole of Hood’s army,” Sherman told Thomas, “leaving you to walk into Atlanta, capturing guns and everything.” Thomas, although naturally cautious, obeyed as ordered.

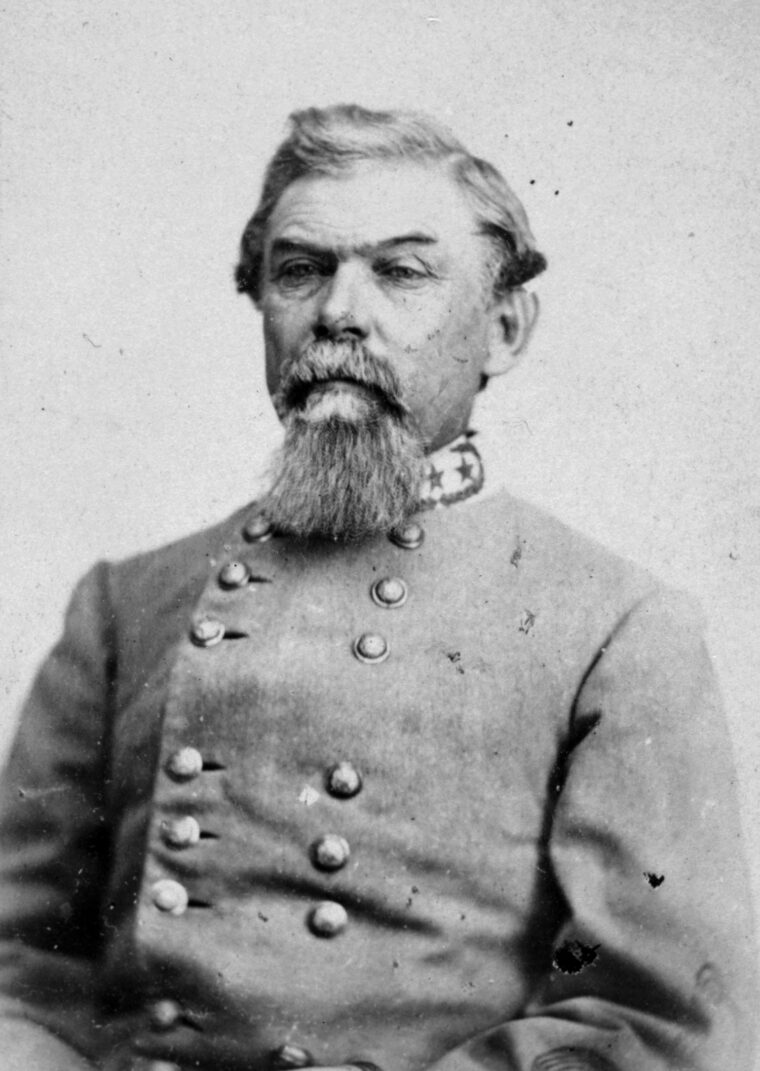

While the Federals neared Atlanta, the Confederates remained in their defensive works. A mile below Peachtree Creek, the infantry corps of Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart was posted on the Confederate left, anchoring the line near the Chattahoochee. Next came Hardee’s corps, holding the center. On the right was Hood’s old corps, now commanded by Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham, whose right brushed against the railroad. Wheeler’s cavalry guarded the eastern approaches to Atlanta. Manning the defensive perimeter immediately surrounding the city were the men of the Georgia Militia under Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith. All told, Hood had 33,750 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, 3,500 artillery, and 1,500 state militia.

A Bold Confederate Plan

Hood viewed himself as a soldier cast from the same mold as Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, a soldier who defied the odds and placed his faith on daring surprise moves against the enemy. As far as he was concerned, the situation at Atlanta called for nothing less. Hood planned to counter Sherman’s overwhelming numerical strength by assaulting a portion of the Federal forces closing in. His immediate target would be Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland as it passed over Peachtree Creek north of the city. If carried out properly, the attack could catch the Federals straddling the wide, deep stream. They would be helpless—or as helpless as the battle-hardened Union soldiers ever got.

In the late evening of July 19, Hood assembled his chief subordinates to go over his offensive plan. He told Hardee and Stewart to be ready to strike Thomas by 1 pm, with the attack starting on the Confederate right wing in echelon by divisions at intervals of 200 yards. Hood admonished his listeners that everything south of Peachtree Creek must be taken at all hazards. Stationed on Hardee’s right, Maj. Gen. William B. Bate’s division would lead the attack, followed by Maj. Gen. William H.T. Walker and Brig. Gen. George E. Maney’s divisions. Hardee was to keep Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne’s infantry division in reserve. The divisions of Maj. Gens. William W. Loring, Edward C. Walthall, and Samuel G. French, all of Stewart’s corps, were to follow Maney’s men. Hood hoped his plan would result in driving the enemy west to the Chattahoochee River, where they would have their backs to the water. On his right flank, Hood was depending on Wheeler’s cavalry and Cheatham’s infantry to keep Schofield and McPherson from coming to Thomas’s aid. A swift, hard blow against the Army of the Cumberland might eliminate half of Sherman’s force before help could arrive. With a little luck, Hood might just succeed where Johnston had failed.

Advancing on Atlanta

Unfortunately for the new Confederate army commander, luck deserted him in the earlier hours of Wednesday, July 20. While Hood was wrapping up his instructions to his generals, Sherman was issuing his own directions to the heads of his armies. They were to start a concentrated move on Atlanta no later than 5 am and be prepared to accept battle as they advanced. McPherson’s troops commenced their move west from Decatur, and within a few hours, advance parties of his XV Corps under Maj. Gen. John A. Logan were within 21/2 miles of the city. At noon, two 20-pounder Parrott shells exploded near the corner of Ellis and Ivy streets in the center of Atlanta, killing a young girl who was walking through the intersection with her parents. The long-feared Yankee assault on Atlanta seemed to have gotten under way.

Responding to the threat from the east, Hood felt compelled to shift Cheatham’s division farther east to halt the oncoming Logan. Cheatham moved as ordered, but proceeded two miles farther than he should have, creating a wide gap between him and the rest of the army and delaying the general attack for two hours while Stewart and Hardee realigned themselves on Cheatham’s left. Meanwhile, Thomas’s men crossed Peachtree Creek and began digging in on the high ground a half mile south of the stream.

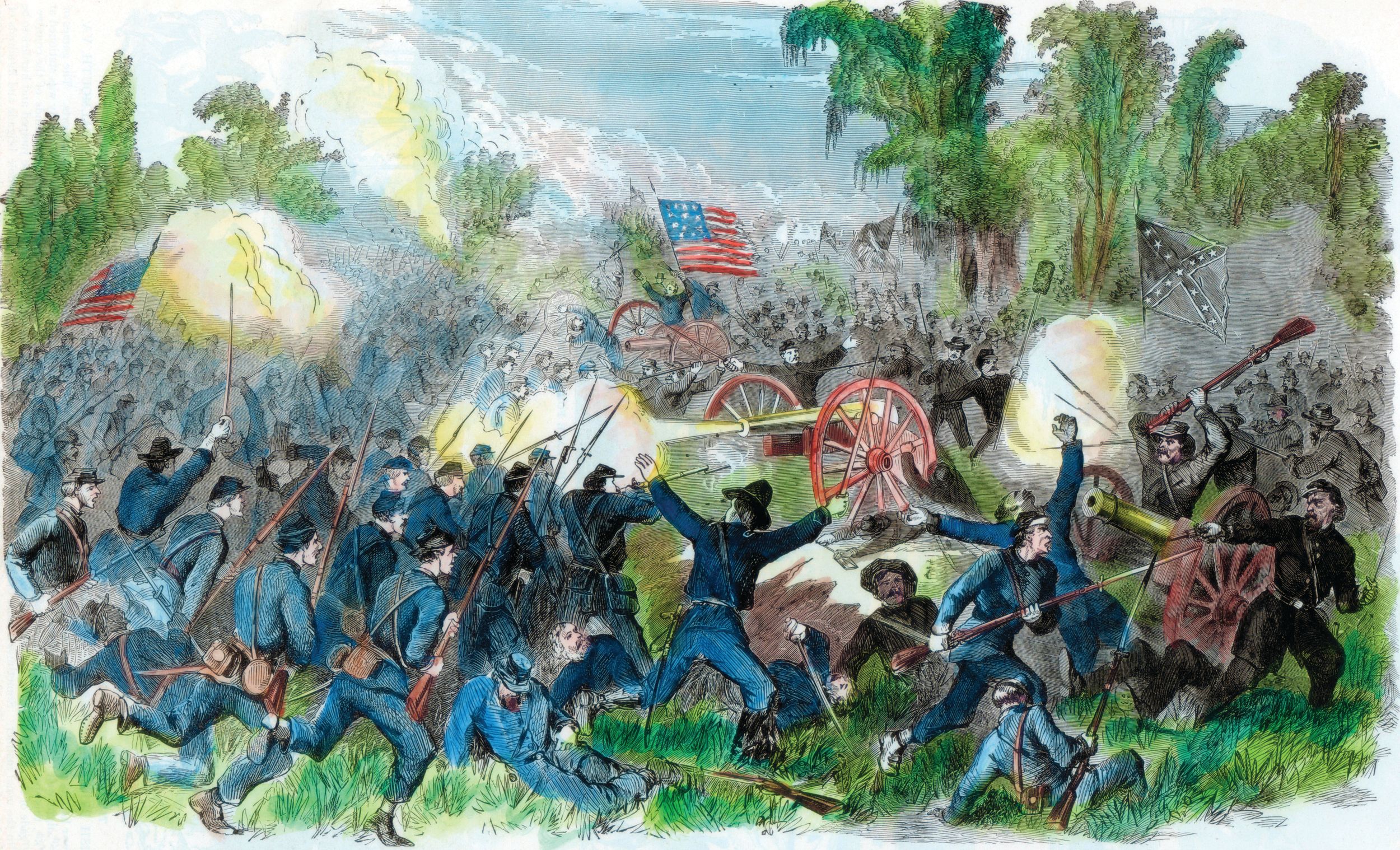

At 2 pm, Hardee at last sent word to Stewart that he was ready to attack. “We must carry everything, allowing no obstacle to stop us,” Stewart told his men, adding perhaps unnecessarily that the fate of Atlanta depended on the outcome of the battle. Maney’s division moved off into the woods in front of them. Noticing this activity on his right, Loring assumed the attack had begun. He then started his own columns forward, running into enemy troops a half hour later in the center of the Rebel front. This was not part of Hood’s original plan. On the contrary, Bate was to have started the battle on the Confederate right by hitting Brig. Gen. John Newton’s division of Howard’s IV Corps. Hardee finally told Bate to move out at about 3:15, but the latter, after marching nearly a mile through thick underbrush, made no contact with the enemy. The reason was simple: Bate had unknowingly entered the gap between the Union Army of the Cumberland and the Army of the Ohio. Blissfully unaware, he continued moving to the west in search of the enemy. Soon he heard the rattle of muskets and the roar of cannons.

What Bate heard was the initial contact made between Walker’s and Newton’s troops. The Confederates were formed in two battle lines and had stumbled on the positions of some of Newton’s brigades supported by Captain Wilbur Goodspeed’s battery of four 12-pounders. Moving swiftly, the Georgians under Brig. Gen. Clement Stevens captured a part of the Union earthworks situated to the right of Peachtree Road. The Georgians had little time to enjoy their success, however. A fierce flanking fire forced them back and mortally wounded Stevens. Repeated attacks failed to carry the Union position, and by 6 pm the fighting on this part of the battlefield was reduced to scattered exchanges of musket fire.

The Confederates Halted

By late afternoon, Bate’s wandering column came upon the left rear of the main Union line defended by Newton’s reserve brigade under Colonel Luther Bradley. Aided by two of Goodspeed’s pieces and other cannons from the 1st Illinois Light Artillery Battery, the Federals threw back several Confederate assaults. Because of the heavily wooded terrain, Bate was unable to assemble all his men for a full-strength attack.

On Newton’s right, Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball’s infantry brigade came face to face with Maney’s Tennesseans, who struck the Federal right flank. Kimball was separated from the next Union division in line, Brig. Gen. William T. Ward’s, which was a few hundred yards to Kimball’s right. Fighting raged until 6 o’clock, with Kimball’s men holding firm and inflicting heavy losses on Walker’s and Maney’s forces.

Well before Maney made contact with Kimball’s troops, Loring had been engaged on his left. A spirited charge gained some ground, but a Union counterattack drove the Confederates back to their starting line. On Loring’s right, the brigade under Brig. Gen. Winfield Scott Featherston faced two Federal regiments that had taken positions behind rail fences on high ground known as Collier Ridge. Rushing to attack in three lines, Featherston’s men carried the ridge but could not budge Ward’s main line assembled 50 yards beyond the high ground just captured by the Confederates. A countercharge by Ward drove the Confederates back over Collier Ridge, and repeated tries by the Confederate infantry came to naught. According to Ward, the southerners “were now in the wildest confusion, firing in all directions, some endeavoring to get away, some undecided what to do other, others rushing into our lines.” Men on both sides staggered light-headed in the sultry heat.

“To Stand Longer was Madness”

On Featherston’s left, Brig. Gen. Thomas M. Scott took up the advance. His five Alabama regiments, along with the 12th Louisiana, smashed into the 33rd New Jersey Regiment of Brig. Gen. John W. Geary’s division. The 33rd had been posted on a small hill 500 yards in front of the main Union line. Confederate prisoners had assured Geary—presumably with straight faces—that “there were no large bodies of their troops within two miles.” Geary believed them. “Not a man of theirs,” he said, “was to be seen or heard in any direction.” Suddenly, Scott’s brigade burst from the woods, firing at a range of less than 75 yards. Giving a Rebel yell and blasting away steadily, they rushed the flabbergasted New Jersey regiment. “The fire was terrific,” Lt. Col. Enos Fourat reported. “The air was literally full of deadly missiles; men dropped upon all sides; none expected to escape.” The surging Confederates demanded the surrender of the regiment’s New Jersey state flag; when it was not forthcoming, they simply shot down the color-bearer and carried off the prize. After the Confederates rushed to the top of the hill, Fourat ordered a full retreat. “To stand longer was madness,” he reasoned.

Emboldened by their success, the Confederates continued their advance over Collier Ridge. Veering to their right, they came up against the Ohioans and Pennsylvanians of Colonel Charles Candy’s 1st Brigade, as well as Colonel Ireland’s New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians, supported by two artillery batteries. The Union musket fire was directed by Colonel Benjamin Harrison, a future United States president. Seeing the Confederates disordered by the storm of lead directed at them, Harrison launched a counterattack across Tanyard Branch Creek, crashing into the enemy and sending them reeling backward in disarray.

As Scott’s right wing was being routed, his left continued the assault with some success. After ascending Collier Ridge, the Confederate attackers ran into solid lines of infantry formed by Geary’s other units, supported by eight pieces of artillery. Corps commander Joseph Hooker, a victim of the precipitate Union retreat at Chancellorsville, Virginia, 14 months earlier, rode up to his hard-pressed troops and helped reform their lines. “Boys,” he said calmly, “I guess we’ll stop here.”

As Scott’s men struggled with their opponents, Colonel Edward A. O’Neal led his Alabama and Mississippi regiments in Scott’s wake. The men of O’Neal’s brigade were in good spirits and ready for a fight. As Scott’s command moved out of view, O’Neal’s men swept out of the woods and slammed into the right of Geary’s line. That portion of the Union front was held by Colonel Patrick Henry Jones’s 2nd Brigade, part of Geary’s “White Star” division. Native Irishman Jones had his brigade in good position to receive an enemy assault. Having moved 800 yards in advance of the corps line, Geary intended to hold Collier Ridge’s high ground. He was assured that Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams’s division would move into line to guard his left. That was never done, and Geary was forced to fend for himself.

Not expecting an attack and having recently arrived at their new position, Jones’s soldiers had no time to prepare fieldworks. At 4 pm, O’Neal’s men came into view deployed in some places five deep. Hindered by dense and tangled underbrush, they nevertheless climbed the ridge and overran Geary’s right, causing three enemy regiments to skedaddle to the rear. Jones’s men were forced back to the area they had held earlier in the day.

“Yelling like Demons”

As the Union regiments withdrew in panic, Geary strove to save his command and stop the Confederate breakthrough. Bending his line at right angles, he was able to deliver a withering fire on his pursuers. The appearance of Williams’s division on his right added to the enemy’s discomfort. In the face of such heavy fire, O’Neal ordered his men to retreat. He later complained that he would have carried the Federal position if he had been properly supported on the right.

As O’Neal led his men out of a potential death trap, the fighting at Peachtree Creek morphed into a long-range musketry duel, with neither side attempting to advance or retreat. At one point, the Confederates managed to overrun a section of Captain Henry Bundy’s 13th New York Independent Battery. The firing was so heavy that one of the gunners was struck by nine rounds, another by seven. “So hot was the rebel infantry fire,” said one New Jersey adjutant, “that many of the spokes of the wheels of [my] pieces were almost cut in two.”

In the Union rear, soldiers of the 123rd New York were napping, playing cards, and discussing rumors that the enemy was in full retreat. They expected to march into Atlanta the next day. Corporal Rice Bull and his companions were congratulating themselves “on this unexpected good luck when suddenly there was a rifle shot on our front.” Then came the familiar Rebel yell. “A look of surprise and almost consternation came to every face,” Bull recalled. The New Yorkers quickly formed a defensive line and managed to drive back the Confederates, who were “yelling like demons” as they pressed the attack. Among the slain attackers was Major William L. Preston, the brother of Hood’s erstwhile fiancée, Richmond socialite Sally “Buck” Preston.

Disappointing Subordinates

By 6 pm, the firing had ended. Bitterly disappointed by the result and furious that all of his command had not entered the fight, Hood raged at his subordinates. It was too late. With the Battle of Peachtree Creek concluded, the two sides assessed their losses. On the Confederate side, Stewart’s corps had lost about 1,450 killed, wounded, or missing, while Hardee suffered 1,500 casualties. Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland incurred about 1,750 killed, wounded, and missing.

Thomas hoped the victory at Peachtree Creek would satisfy Sherman, but quite the opposite was the case. Having spent the day with McPherson’s troops east of Atlanta, Sherman did not even hear about the battle until after it was over. Instead of being satisfied with the result, Sherman complained about lack of coordination between his armies. With Hood engaged against Thomas, he said, Schofield and McPherson should have pushed through the weakened enemy lines and taken Atlanta. He neglected to explain why he had never given such a follow-up order.

Hood, for his part, was equally disappointed in Hardee’s performance. Had Hardee attacked with as much vigor as Loring and Walthall, he said, the Confederates would have carried the day. Hood had a point—Hardee had committed a relatively small portion of his troops, and even these were put into battle piecemeal. Not only did he fail to commit Maney’s entire division at the critical point of the battle, but Hardee also held back Cleburne’s much-feared division, which doubtless would have added ferocity and numbers to the attack. As it was, the brunt of the Confederate attack had fallen to a mere half-dozen brigades.

Peachtree Creek was the opening act in the final struggle for Atlanta. The battles of Atlanta, Ezra Church, Utoy Creek, Jonesboro, and Lovejoy’s Station remained to be fought before the town fell to the Federals. What made Peachtree Creek unique in the series of fights for the city was that it represented the last best opportunity for the Confederates to avoid its fall. Because they were not yet physically and spiritually ruined by Hood’s wasteful battles against far superior odds, the fight at Peachtree Creek was the Confederates’ only realistic hope of preventing the capture of their most important western city.

Davis, realizing belatedly that his appointment of Hood had been a disaster, told an audience in Macon that he had put “a man in command who I knew would strike an honest and manly blow for the city, and many a Yankee’s blood was made to nourish the soil before the prize was won.” One listener, at least, was not impressed. Joseph Johnston, Hood’s luckless predecessor, began referring to Hood derisively as “the Striker of Manly Blows.” At this point in the war, such blows—however manly—were not enough to save Atlanta, or ultimately the Confederacy as a whole.

Joseph Wheeler served as both a general in the Confederate Army, then some years later, served as a general in the US Army during the Spanish-American War. He retired as a major general, US Army.