By Ron Gilliam

As he read the decrypt of the radiogram from Admiral Harold Stark, Chief of Naval Operations, several things bothered Admiral Thomas C. Hart, the Commander in Chief of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet based at Manila, Philippines, besides the tortured syntax and curious terminology. The message read:

“President directs that the following be done as soon as possible and within two days if possible after receipt this despatch. Charter three small vessels to form a quote defensive information patrol unquote. Minimum requirements to establish identity as United States men-of-war are command by a naval officer and to mount a small gun and one machine gun would suffice. Filipino crews may be employed with minimum naval ratings to accomplish purpose which is to observe and report by radio Japanese movements in the West China sea and Gulf Of Siam. One vessel to be stationed between hainan and hue one vessel off the indo-china coast between Camranh Bay and Cape St. Jacques and one vessel off pointe de camau. Use of Isabel authorized by president as one of three vessels but not other naval vessels. Report measures taken to carry out presidents views. At same time inform me as to what reconnaissance measures are being regularly performed at sea by both army and navy whether by air surface vessels or submarines and your opinion as to the effectiveness of these latter measures. Top Secret”

For a start, Hart thought that sending out a “defensive information patrol” would “consume effort we could ill spare from more valuable objectives.” Intelligence on the Japanese invasion force massing on Hainan Island and in Vichy-controlled French Indochina (Vietnam) was already available from several sources, having in fact been the principal reason for Washington’s war-warning message to all U.S. Pacific commands on November 27. A key source was his own Navy Patrol Wing 10. On November 25, tipped off by a rumor from Hong Kong, Hart had surreptitiously initiated aerial surveillance of Camranh Bay, on the central Vietnam coast, using a couple of Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats and had personally written and dispatched the first report the same day. Then, on November 30, Admiral Stark, with presidential approval, ordered him to do what he had already been doing on his own authority for five days.

The December 1, 1941, order’s excruciatingly specific detail, extraordinary as it was inappropriate to a fleet commander, also perplexed Hart. Why did the president specify surface reconnaissance? Hart had flatly stated in his November 25 report that the situation most clearly required air observation because high land makes examination from ships both difficult and slow. Also, picket ships would run greater risk than aircraft. As it was, one of his Catalinas had barely escaped from closing Japanese fighters by dodging into cloud.

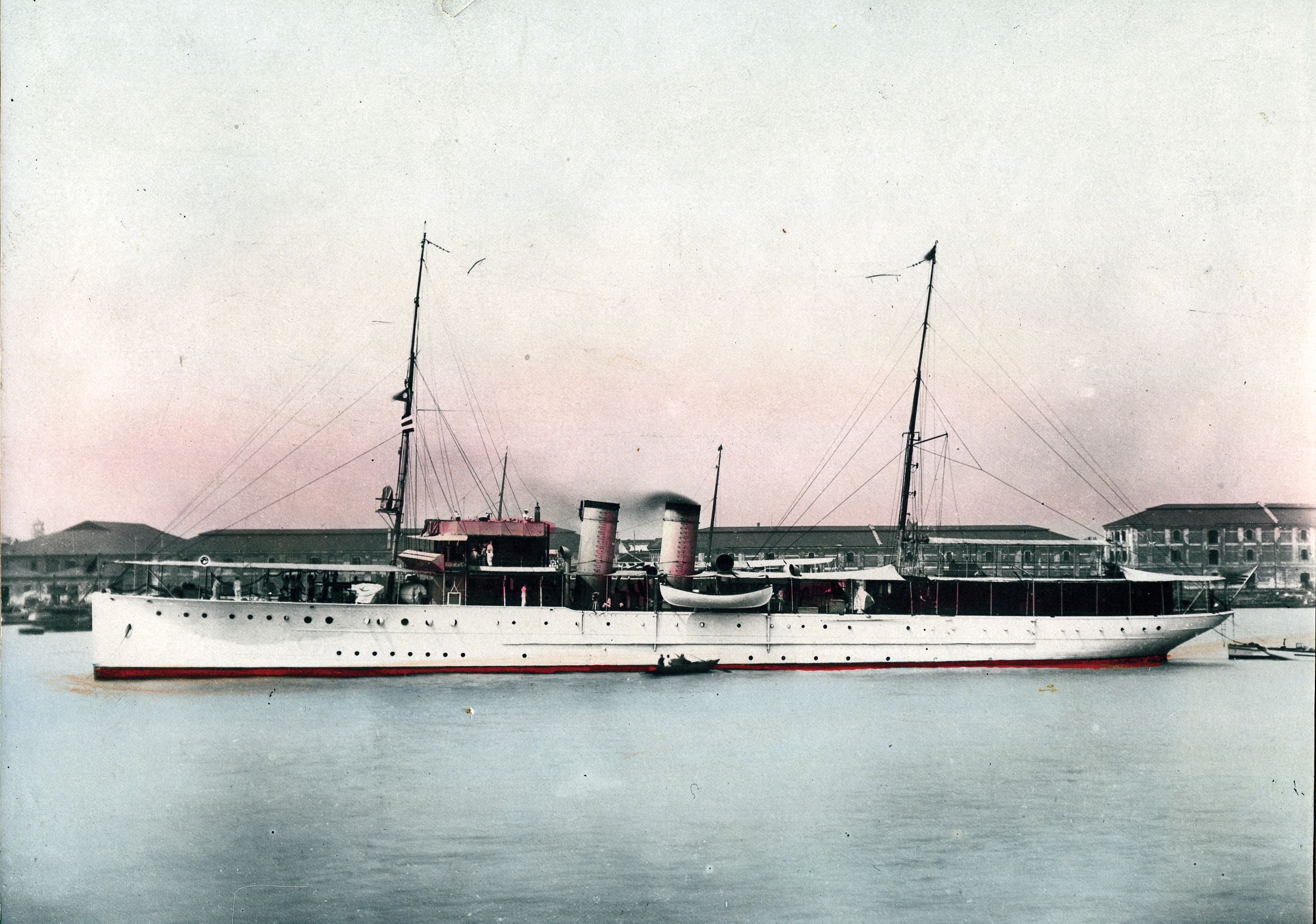

Why did the president specifically forbid using naval vessels, except the Isabel? The Asiatic Fleet—mainly a “show the flag” force of three cruisers, 13 four-stack, World War I-vintage destroyers, and no fighter aircraft—counted 27 submarines, which were fully capable of surface reconnaissance, clandestine at that. Isabel, Hart’s relief or holiday flagship, was a trim 900-ton private yacht converted during World War I for convoy escort. Hart had noted that with her white hull, buff deckhouse, twin stacks, and inconspicuous armament of two 3-inch deck guns and two 3-inch antiaircraft guns, Isabel might pass at a distance for a small Chinese merchantman. He wondered whether Roosevelt had also noticed while viewing the copy of Jane’s Fighting Ships he had always kept handy since his time as assistant secretary of the Navy during World War I.

Anticipating War

By mid-1941, it was no secret that, though opposed to colonialism, Roosevelt was convinced that if Japan cut Britain’s imperial lifeline to the Far East, democracy would be lost in Europe and the Japanese militarist government would control all of Asia. At the Argentia Conference off Newfoundland in early August 1941, Roosevelt had assured British Prime Minister Winston Churchill that Britain could count on American armed support in the event of a Japanese attack on the British and Dutch colonies in the Far East. Although Admiral Hart was not privy to that agreement, he must have guessed the existence of something like it, since after Japanese forces occupied southern French Indochina in mid-1941, he and his staff had been participating in mutual defense coordination conferences at British Far East Fleet headquarters in Singapore.

In late November, the president’s war council had held a series of meetings to discuss the problems posed by the burgeoning Japanese threat. One problem was that in order to provide armed support to the British Roosevelt would have to have a declaration of war from Congress, which reflected an isolationist and pacifist public opinion of less than 20 percent in favor of America’s entering a war.

At the November 25 war council meeting, which had resulted in the Thanksgiving Day war-warning message, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson raised the question of how to maneuver the Japanese into firing the first shot. The council had no solution then, but at the November 28 meeting, called to discuss the president’s sending of a personal message to Emperor Hirohito, someone had brought up the Panay Incident, the accidental sinking by the Japanese of a U.S. Navy gunboat on the Yangtze River in China in December 1937. Although no record remains from the meeting of December 1, which resulted in the “three small vessels” message, historians have conjectured that it must have addressed the problem of how to get the United States into the war if the Japanese attacked only Singapore, Thailand, or the Netherlands East Indies, and not the Philippines or other U.S. territory in the Far East, as well as specifically how to devise an incident in which Japan would commit the first overt act by sinking one or more American warships.

Provoking an “Isabel Incident”?

At first, the requirement for Filipino crews annoyed Admiral Hart. He would have to get them from the Insular Force, a naval auxiliary, and ignore their legal restriction to Philippine waters. According to contemporary news accounts, relations were currently touchy with the Commonwealth of the Philippines, which the United States was grooming for the coming of independence in 1946. President Manuel Quezon had exasperated the Roosevelt administration by openly considering requesting early independence and hinting at a subsequent offer of Philippine neutrality to appease Japan. The Panay Incident four years earlier was still fresh in Hart’s mind. Could the requirement for Filipino crews be to guarantee the loss of Filipino sailors in an “Isabel Incident” and serve to rally Filipino popular opinion behind the United States?

Whatever its real intention, Hart knew the presidential directive was a definite and unequivocal order, so worded as to bear the highest priority, and had to be carried out. He told fleet operations officer Commander Harry Slocum to have Isabel’s captain report to him first thing the next morning and to find two small vessels for charter.

Isabel’s skipper was Lieutenant John Walker Payne, Jr. Owing to the ship’s generally poor condition—age and long tropical service had reduced her 26-knot top speed to about 15—her captaincy had been down-rated to lieutenant. The last lieutenant commander selected to captain the Isabel had, after inspecting the vessel, retired to his cabin and shot himself.

Admiral Hart knew and liked Payne and personally briefed him on the presidential directive, requiring Payne to memorize his verbal orders and recite them back. No one was to know the actual mission of the Isabel except the admiral and Lieutenant Payne until the vessel was at sea. Then the executive officer was to be taken into confidence. They were to proceed to Camranh Bay, approach the coast only under cover of darkness with dimmed running lights to give the appearance of a fishing craft, and report in code all movements of Japanese ships within a few hours of sighting. For a cover story, a fake operational dispatch was transmitted, ostensibly ordering Isabel to search from Manila west to the vicinity of the Indochina coast for a lost Navy PBY plane.

Payne fueled and provisioned at Cavite Navy Yard, and, since his crew was all American, took on five Insular Force Filipinos. Hart had ordered him to fight the ship as necessary and to destroy it rather than let it fall into enemy hands. Accordingly, he ordered all removable topside weights cleared, including motorboats and gangways, and took on board an additional pulling whaleboat and life rafts. All confidential material except one cipher was turned in. Once at sea, Payne related Hart’s orders to his executive officer, Ensign Marion Hugo Buaas, a 1938 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy who had recently come over from the cruiser USSHouston. Payne told Buaas that the admiral suspected that the president, anxious to get into the war against the Axis, thought the voyage of the Isabel into Japanese-controlled waters off Indochina would accomplish this goal.

Isabel left Manila on December 3, 1941 (Manila time). That same day, one of Hart’s Catalinas counted 50 Japanese ships, including transports, cruisers, and destroyers, riding at anchor in Camranh Bay, Isabel’s destination. At 7 am on December 5, a Japanese naval reconnaissance plane appeared. It circled at an altitude of 1,000 feet, range 2,000 yards, and took pictures. The Americans also took photos of the Japanese aircraft, which shadowed them all day. At 7 pm, the coast of central Vietnam was sighted 22 miles distant. Then, just 10 minutes later a CINCAF (Commander in Chief Asiatic Fleet) message ordered them to return to Manila immediately.

“Receipt for One Schooner”

Hart had mentioned his intention to recall Isabel for another mission in his December 4 reply to Admiral Stark’s question about regularly performed reconnaissance measures, claiming “she is too short-radius to accomplish much and since we have few fast ships her loss would be serious.”

That claim, given her executive officer’s assessment of her condition and speed, raises the question of whether Admiral Hart had sent her out in a prompt response to the presidential directive while hoping to have time to substitute a chartered civilian vessel before any action. In the same radiogram, Hart stated, “Though it is improbable that [I] can start any chartered vessels within two days, [I] am searching for vessels for charter that are suitable but cannot yet estimate time required to obtain and equip with radio.”

That same morning, Slocum was inspecting an 83-foot, 67-ton, two-masted auxiliary schooner. Called the Lanikai, she had been built in San Francisco in the early 1900s for Hawaiian inter-island service, used by the Navy in World War I, and featured in a Dorothy Lamour movie in the 1930s. The Lanikai was chartered for a dollar a year, with four or five Filipino crewmen in the bargain. Two days later, another schooner half the size of the Lanikai, the Molly Moore, was chartered. Her commissioning, however, was overshadowed by the December 7 attack on Pearl Harbor.

Later on the morning of December 5, the last two gunboats of the Yangtze Patrol, having slipped out of Shanghai the night of November 29 in a run for the relative safety of the Philippines, steamed into Manila Bay. Aboard the gunboat Oahu, three-year patrol veteran Lieutenant Kemp Tolley received the message, “LT. TOLLEY DETACHED, PROCEED IMMEDIATELY TO COMMAND USS Lanikai…” with instructions to report to fleet headquarters as soon as possible.

Thrilled by the prospect of his first command 12 years after graduating from the Naval Academy, Tolley was puzzled that no one had heard of the Lanikai. At CINCAF headquarters Commander Slocum explained that the ship had just joined the Navy and that Tolley was to arm her with a cannon of some kind and one machine gun, provision her for a two-week cruise, get a crew aboard, and be ready to sail in 24 hours.

Tolley exclaimed that Navy yard procedures would take weeks, perhaps months. “The rules do not apply in this case,” Slocum retorted. “Cavite has been directed to give you the highest priority, on your verbal request, without paperwork of any kind. Of this you can be absolutely assured; the President himself has personally ordered it.”

At Cavite Tolley was told, “Sign this receipt for one schooner and tell me what you want!” Phone calls mobilized yard resources. A 3-pounder quick-firing boat gun of Spanish-American War vintage had already been located and determined to be the biggest gun that could be fired safely from the schooner’s deckhouse. Two .30-caliber Lewis guns left over from World War I completed the armament, apart from Thompson submachine guns and hand grenades. The Insular Force had assigned half a dozen Filipinos to the crew. They spoke no English and were unsure of what was happening. “They amiably accepted the bags of white uniforms,” Tolley noted, “then immediately dug out the little round white sailor hats and proudly put them on.”

At 9 am on December 5, Lanikai became a United States Navy man-of-war, probably the last one under sail. Chief Gunner’s Mate Merle L. Picking, the only other American aboard besides Tolley, hoisted the commission pennant while the Navy yard band played the national anthem and several hundred yard workers looked on. Then Lieutenant Tolley formally accepted the ship from the captain of the yard, the band played “God Bless America,” and the loading of stores and equipment resumed.

American crewmen arrived by ones and twos. Chief Boatswain’s Mate Charlie Kinsey stood on the dock, walked forward, squinted at the ship’s nameplate, then called down in a thick Georgia drawl to Chief Picking, polishing the 3-pounder’s shiny brass pedestal. “I’ve got orders to the Lanikai, but this cain’t be it!” After assuring him this was indeed it, Tolley asked him, “Have you ever been in sail before, Boats?” Tolley was well aware that his own experience in sail was limited to a catboat on the Severn at Annapolis.

“ORANGE WAR PLAN IN EFFECT. RETURN TO CAVITE”

On December 6, in spite of the heroic efforts of all concerned, Lanikai was still in port. The biggest problem was the radio. The yard had installed a good receiver but had no transmitters available. The existing transmitter was “a homemade rig, probably made by a radio shop in Manila or by some ham,” the chief radioman recalled, and it refused to emit a beep. “Evidently, one of the windings on the plate transformer was open, as I could never obtain any high voltage.”

By now, Lieutenant Tolley suspected that the cruise—whatever its mission—would likely be one-way, and he stored most of his possessions, leaving his sword, class ring, will, and a last letter home with a friend. He would never see any of it again. What he brought aboard—typewriter, camera, a few khaki shirts and slacks, sneakers, steaming cap with grommet removed, a set of white shorts and shirt—fit easily into a small locker in the captain’s cabin. “If I managed to survive,” he thought, “it would be by swimming, in which case excess baggage would be no help.”

On December 7 (Manila time), ready or not, USS Lanikai was to put to sea. Tolley got no admiral’s briefing, just a small envelope that Commander Slocum passed him with the instruction to open it only when clear of Manila Bay. “I can tell you that you are headed for the coast of Indochina. If you are queried by a Japanese man-of-war, you are to explain you are looking for a downed U.S. Navy patrol plane.” When Tolley told him his radio was not transmitting, Slocum breezily told him to have his radioman work on it en route.

Tolley’s second concern was fresh water; Lanikai was designed for a crew of five and now carried 19. “You have a set of international signal flags, don’t you?” Slocum responded, adding sardonically, “If you run short of water, ask a passing Jap for some.” Years later, he confessed to Tolley, “I feel sure you realize that by the time you were ready to sail that almost all of us understood that time had run out and that whatever FDR had in mind could in all probability never be realized.”

By 2:10 pm, the last three crewmen, the engineer, pharmacist’s mate, and the long-awaited radioman had reported aboard, and a yard tug towed Lanikai clear of her mooring. By 2:15, she was under way on auxiliary power, shifting to her main propulsion at 2:20 with the hoisting of the jib staysail and forestaysail. There was no hurry crossing Manila Bay; ships were permitted to traverse the minefield at the entrance only in daylight—even though, as Admiral Hart had complained to OPNAV on October 7, the ancient mines were so covered in barnacles as to be useful only for bluff.

The sun was low when Tolley dropped anchor off Corregidor. The cook served out the crew’s first supper at sea, and everyone turned in early. Around 3:30 am, December 8 (9:30 am December 7, Honolulu time), the radioman nudged Tolley awake with a message from fleet headquarters: “ORANGE [i.e., Japan] WAR PLAN IN EFFECT. RETURN TO CAVITE.” Tolley decided to let the crew sleep until dawn and went topside into the cool night air. He noticed that the lights on Corregidor had gone out and guessed they would not be coming on again for a long time.

At 5:35 am, three hours after the first bombs fell on Oahu, Isabel gained entrance to Manila Bay, having been shadowed all the previous day by a Japanese twin-engine reconnaissance bomber. When Payne reported to Hart, the admiral looked surprised: “I didn’t expect to see you again,” he said.

The Japanese had identified Isabel and refrained from attacking her in order not to set off alarms before the Pearl Harbor raid. The day before, however, Japanese fighters chased or fired on three British and Australian patrol planes off the Pointe de Camau, which had been Lanikai’s assigned station. Several hours after Isabel docked, Japanese warplanes hit Clark Field on Luzon. World War II had overtaken the United States.

Thirty years later, over lunch with Rear Admiral Kemp Tolley, retired Admiral Thomas Hart remarked to another guest, “I once had the unpleasant requirement to send this young man on what looked like a one-way mission,” and briefly related Lanikai’s narrow escape. “Would you tell [us],” Tolley asked him, “if you think we were set up to bait an incident, a casus belli?”

“Yes,” Hart replied, “I think you were bait! And I could prove it. But I won’t. And don’t you try it, either!”

As I recall, RADM Tolley wrote an article about this in the US Naval Institute Proceedings, and later he wrote an interesting memoir his life.