By Victor Kamenir

Driven and energetic in his youth, by the late 1860s French Emperor Napoleon III was a shadow of his former self. The ruler of France’s Second Empire was overweight, melancholic, and in poor health. Born Charles-Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, he had lived his whole life in the shadow of his illustrious uncle, Emperor Napoleon I.

After Napoleon I’s defeat in 1815, Louis-Napoleon was exiled as a child with the rest of the Bonapartes. He eventually returned to France, winning his way into politics. The French elected him to serve as the president of the Second Republic in 1848. Three years later, Louis-Napoleon proclaimed himself Emperor Napoleon III. But Napoleon III met his match in Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.

Prussia’s defeat of Denmark in the Second Schleswig War of 1864 resulted in Prussia’s annexation of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. Afterwards, Bismarck secured an alliance with Italy in order to wage a two-front war against Austria. When Austria declared war on Prussia in June 1866, the Prussians invaded Austria and smashed the poorly led Austrian army at Konnigratz on July 3. Austrian emperor Franz Joseph I sued for peace three weeks later.

Following the victory over Austria, Bismarck drove the unification of German states with an iron hand. He stitched together the smaller German states of northern Germany into the North German Confederation in July 1867, and also exerted his influence over the substantially larger states of southern Germany, including Bavaria, Baden, Saxony, and Wurttemberg. Thus, the previously disparate German states came under the guidance and protection of Prussia. Bismarck’s efforts laid the ground work for eventual German unification.

Bismarck’s drive for German unification was at odds with Napoleon III’s quest to limit Prussian expansion. Bismarck intended to furnish Emperor Napoleon III with a reason to declare war on Germany. It was all part of a well-choreographed scheme by Bismarck to defeat France and complete the unification of Germany.

After the Spanish Queen Isabella II was deposed in 1868, the new Spanish government began the search for a suitable monarch. Both France and Prussia advocated for their respective candidates for the Spanish throne. Spain offered the throne to German Prince Leopold von Hohenzollern, a cousin of Prussian King Wilhelm I in June 1870. Prompted by Bismarck, the prince reluctantly accepted the offer.

Napoleon III found the situation entirely unacceptable for it would mean that France was bordered on all sides by Prussian allies. Bringing all of his political clout to bear, Napoleon III pressured Leopold, who withdrew his candidacy on July 12. Moreover, the French emperor demanded that Prussian King Wilhelm I also acknowledge in writing Prussia assurances not to cause future affront to France.

In what became known as the “Ems Dispatch,” Bismarck insultingly gave a negative reply designed to infuriate the French people. The actual dispatch was a Prussian internal memorandum reporting the demands made by the French ambassador. Bismarck released a statement to the press that stirred up emotions in both France and Germany. Bismarck made it seem as if the French government had insulted the Prussians. The French government, angered by the Prussians, declared war on Prussia on July 19, 1870, despite Napoleon III’s misgivings on the matter.

The French were confident of victory. “So ready are we, that if the war lasts two years, not a gaiter button would be found wanting,” wrote French Marshal Edmond Leboeuf, who served as France’s minster of war from August 21, 1869, to July 19, 1870. Despite some improvements that Napoleon III had instituted after the army’s poor showing in both the Crimean War of 1853-1856 and the Italian War of 1859, the French army was in poor shape. Specifically, its logistics, administration, and training all were in shambles. France’s standing army of 600,000 soldiers was backed up by an additional 400,000 poorly trained reservists. The core of the reserve was long-serving veterans who were well past their prime.

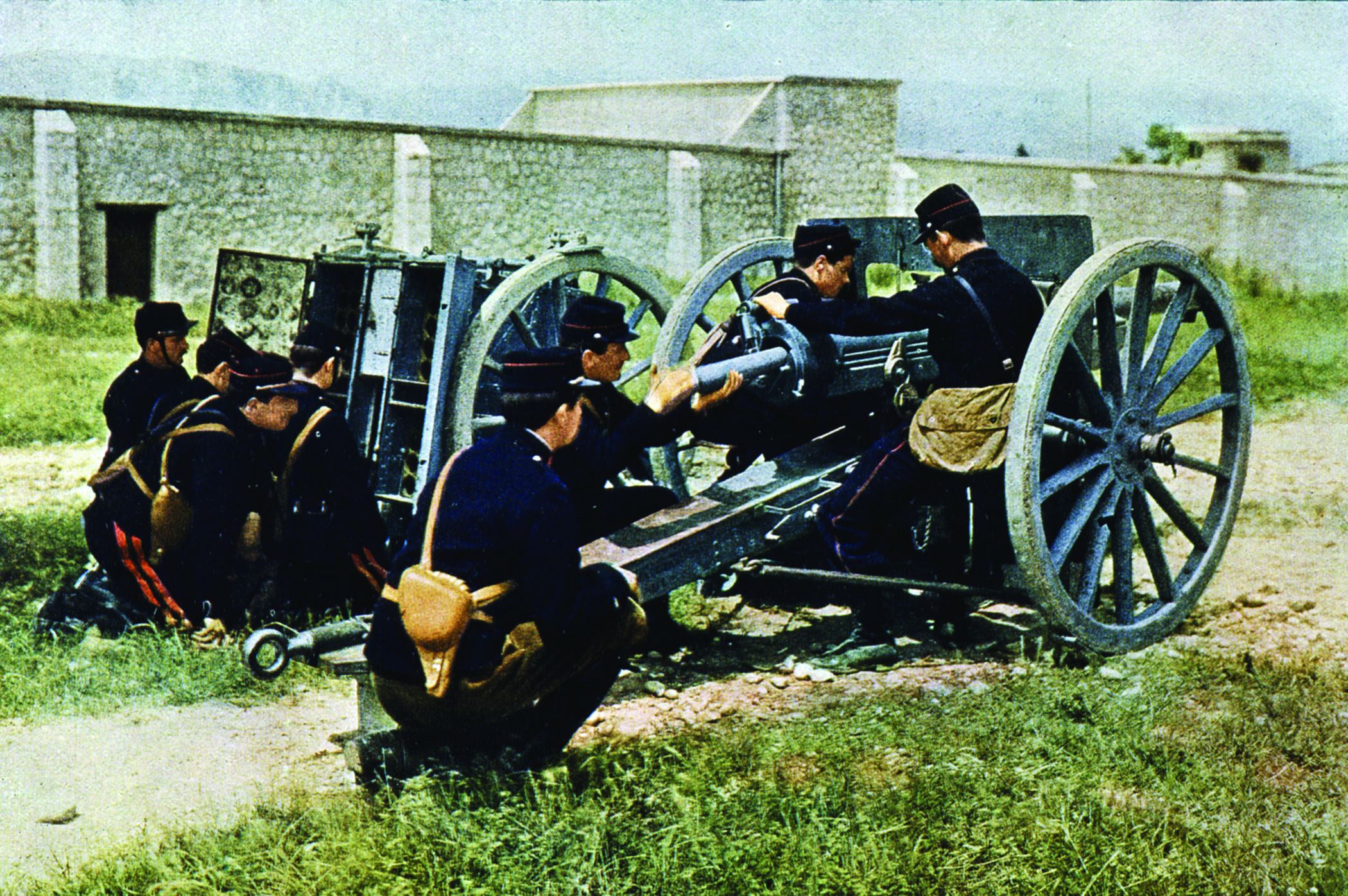

The French armed their soldiers with the superb Chassepot needle gun, which was superior to the Prussian Dreyse needle gun in range, accuracy, and stopping power. The French army’s La Hitte muzzle-loading cannons made of bronze, however, were substantially inferior to the Prussian army’s Krupp breech-loading guns made of steel. The Prussian Krupp guns outshone the French guns in terms of accuracy, range, and rate of fire. Even though its field artillery was inferior, the French army possessed 25-barreled Mitrailleuse volley guns, which could easily shatter an enemy infantry charge.

With the exception of the French Guards, the French army did not have a permanent corps and division structure and their formation immediately before the war was to have a negative effect on army cohesion. Furthermore, the French army lacked detailed war plans, which its staff officers had to create from scratch once war was declared.

In contrast, Prussia was ready for war. Under the leadership of Generalfeldmarschall Helmuth von Moltke, the excellent Prussian General Staff had been working on detailed plans for war with France since 1866. Reforms begun in 1858 had continued under Prussian Minister of War Albrecht von Roon. These reforms transformed the Prussian army into a well-oiled war machine that performed impressively in the conflicts with Denmark and Austria.

The Prussians also excelled in training and martial discipline. The Prussian army conducted regular training by which it instilled discipline in its officers and soldiers. Under compulsory military service, each 20-year-old male served three years on active duty, then four years in the reserves, and lastly five years in the Landwehr militia. Territorial expansion further increased the army and military reforms were extended to the armies of the North German Confederation as well. The Prussian-led confederation could field 1.2 million men.

The Franco-Prussian War began on July 19, 1870. From the outset, the war went badly for France. In the so-called frontier battles, the Prussian forces enjoyed numerical superiority and qualitative advantage in artillery. Even though the French lost a string of battles on the frontier, their infantrymen inflicted heavy casualties on the Prussians with their Chassepot rifles.

After the defeat at the pitched battle at Gravelotte-St. Privat on August 18, Marshal Francois Bazaine’s Army of the Rhine became trapped in Metz by elements of the Prussian First and Prussian Second armies. Two other Prussian armies, the Third Army under Prussian Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, and the Fourth Army under Saxon Crown Prince Albert, began advancing on Paris from the west. The two armies were made up of units not only from Prussia, but also from Bavaria, Saxony, and Wurttemberg.

Napoleon III, who initially accompanied Bazaine, departed for Chalons where Marshal Patrice de MacMahon was organizing a relief army of 120,000 men. MacMahon’s initial intentions were to withdraw his army to defend Paris. Napoleon III had taken no steps to lead the army, and therefore MacMahon assumed the duties of commander-in-chief. Charles Cousin-Montauban, who succeeded Leboeuf as France’s minister of war, pressured him into marching to the relief of Bazaine. MacMahon decided on a flanking maneuver to reach Bazaine that would take his Army of Chalons along the Belgian border.

When he learned of the French maneuver, Moltke turned the Third and Fourth armies north to intercept MacMahon. With the Germans in hot pursuit, MacMahon halted his army at Sedan on August 30. He vacillated over whether to withdraw west, to Mezieres, or to push on to Metz via Carignan. Napoleon III joined MacMahon at Sedan the following day with his 70-man retinue that included 40 servants.

Regardless of which direction he chose, MacMahon did not intend to remain at Sedan for long. When General Felix Douay, the commander of the French 7th Corps, suggested the troops dig trenches, MacMahon told him he did not want to hold a stationary position as Bazaine had in Metz; instead, he wanted to be able to maneuver. “I had no intention of giving battle [at Sedan], but I wanted to rally the army and replenish it with food and ammunition,” wrote MacMahon after the war.

At the time, MacMahon believed he was facing no more than 70,000 German troops. It would turn out that he had greatly underestimated the German strength—for the two German armies converging on Sedan totaled 200,000 men and 800 guns. MacMahon also felt a false sense of security in the notion that the Meuse River protected the rear of his army. This was not the case, though, because his troops had failed to blow up the bridge over the Meuse at Donchery as instructed.

The antiquated frontier fortress of Sedan was state-of-the-art in the 17th century, but by the time of the battle it was outdated as a result of improvements in the range and effectiveness of artillery. Situated on a bend in the Meuse River, it offered no real protection from Prussian long-range guns.

Upon his arrival at the frontlines, Moltke found the French army packed into a narrow space between the Meuse River and the Belgian border northeast of the fortress. He considered the possibility that the French, caught in the pincers from east and west, might attempt to escape to the north into Belgium. So he informed Bismarck of the situation in hopes that he could rectify it.

Bismarck took prompt action to deal with this predicament. He informed the Belgian government by telegraph that it must immediately disarm and confine any French troops that crossed into its territory. If the Belgians failed to do this, Bismarck threatened that Prussia would invade Belgium. The Belgians promptly complied.

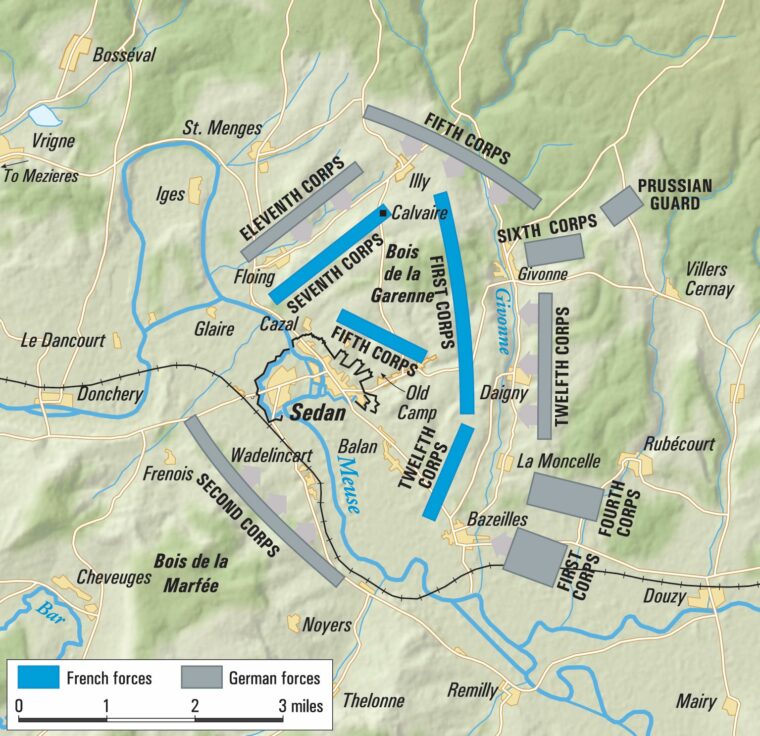

On the evening of August 31, MacMahon arrayed his Army of Chalons in a tight triangle. The French commander deployed his best troops, the XII Corps under General Barthelemy Lebrun, at Bazeilles, about three miles southeast of Sedan. In compliance with the orders, Lebrun deployed his troops on the heights to the north on the western side of the Givonne valley.

General Auguste-Alexandre Ducrot’s I Corps formed the line from the town of Givonne north to Illy, the apex of the French position, where it linked with Douay’s VII Corps, which extended down to the village of Cazal on the bank of the Meuse. The French I and VII Corps were positioned back-to-back northeast of Sedan with the woods of Bois de la Garenne between them. As for General Pierre Louis Charles de Failly’s V Corps, which the Germans had battered the previous day at Beaumont, MacMahon placed it in reserve north of Sedan at a location known as the Old Camp.

Observing the French dispositions, General Ducrot gloomily described the situation to his friend Dr. Charles Sarazin, a surgeon assigned to the French I Corps. “We are in a chamber pot and about to be shit upon,” Ducrot said using the language of a commoner. Douay agreed with the assessment. “I think we are lost,” he told his chief engineer. “It only remains for us to do our best before going under.”

General Emmanuel Felix de Wimpffen arrived from Paris on August 31. MacMahon decided to replace de Failly, the disgraced commander of the V Corps, with Wimpffen. Wimpffen carried a letter of authorization with him from Montauban that authorized him to take charge of the army in case MacMahon became incapacitated. Because of tension between the two high-ranking officers, Wimpffen chose to keep the letter from Montauban secret.

Interpreting French redeployments as a sign that they were intending to withdraw northwest to Mezieres, Moltke put his forces in motion shortly after midnight. The Prussian Third Army under Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia was on the move by 3 a.m. on September 1. By 7 a.m. it had crossed to the north bank of the Meuse River.

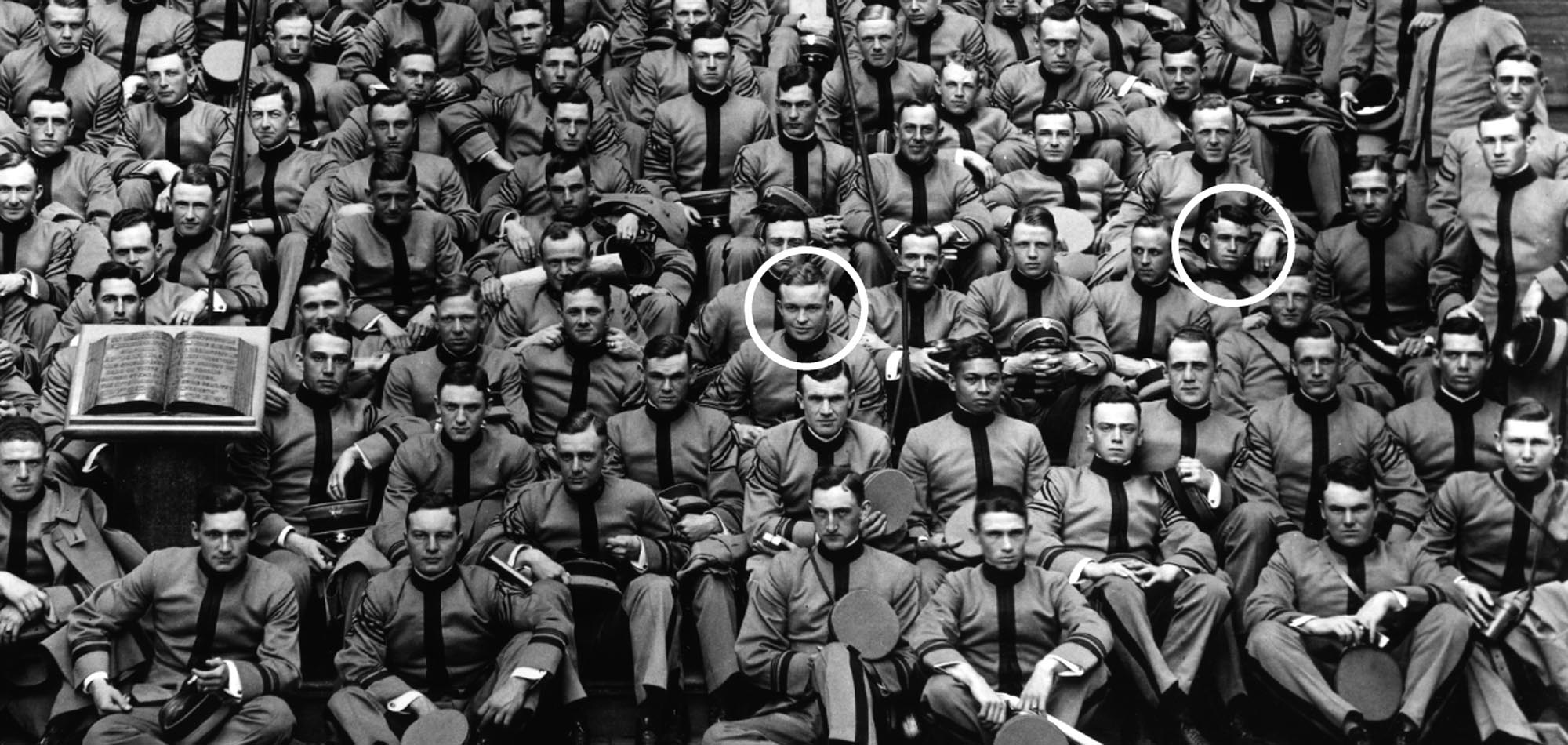

Prussian King Wilhelm was on hand, and he was accompanied by Moltke, Bismarck, and various foreign observers. One of those observers was U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Phillip Sheridan, who had asked U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant to send him to report on the events in the Franco-Prussian War.

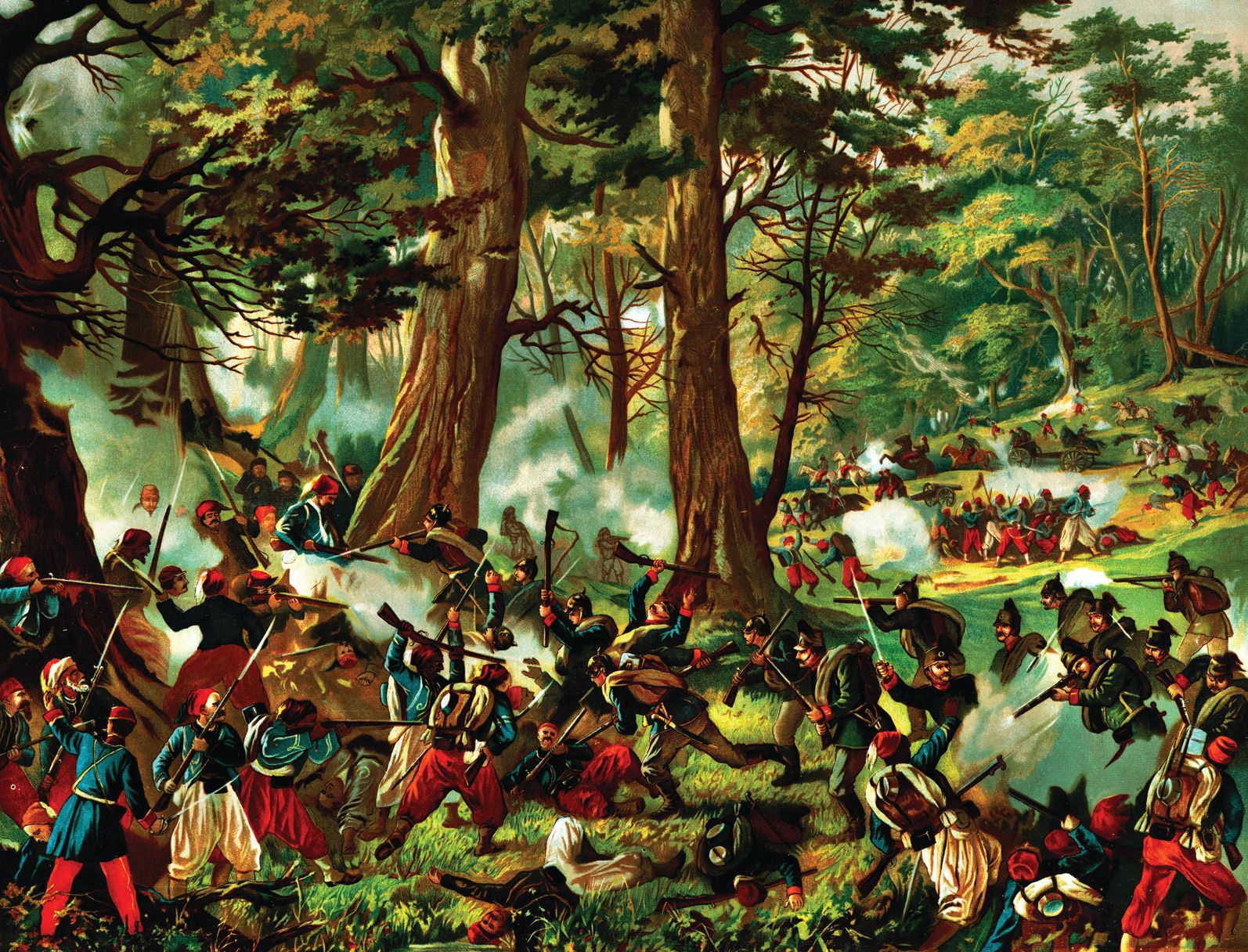

The vanguard of General von der Tann’s I Bavarian Corps of the Third Army, cloaked in the dark of night and fog, crept toward Bazeilles at 4 a.m. Von der Tann hoped to capture the village by surprise. The French 3rd Marine Regiment defended the village. Its veteran troops had transformed the village into a fortress by barricading the streets and creating firing positions in the houses by making loopholes in the walls.

The leading Bavarian companies reached the main street of Bazeilles before French pickets opened fire. As the firefight heated up, commanders on both sides fed more troops into Bazeilles. The Bavarians established a foothold in the northern edge of the village but their attack temporarily stalled when they encountered the French Marines in a strong position in the two-story, elongated structure known as the Villa Beurmann.

Elsewhere in the village, a fresh French Marine regiment drove back the Bavarians until they found themselves in a small enclave on the southern side of the village. “The enemy was pursued in yards, in gardens, in outbuilding and in the houses right up to the attics,” wrote Louis Rocheron, a French marine. “It was hand-to-hand fighting: men butchered and killed each other without pity and with equal fury.”

Von der Tann committed two more brigades to the fighting in Bazeilles as flames licked skyward from the burning village. By that time, the fighting had spread north to the village of La Moncelle. At first light of morning, the artillery of the Saxon XII Corps of the Fourth Army went into action on the heights above La Moncelle. French sharpshooters initially forced several of the Saxon artillery batteries to pull back, but advancing Saxon infantry forced the sharpshooters to retire.

The fighting soon extended north toward the village of Daigny, which was defended by elements of Ducrot’s I Corps. As the fog burned off, more German batteries came on line. The Prussian batteries succeeded in silencing the inferior French artillery batteries which could not compete with the greater accuracy and range of the Krupp guns. Without French guns to protect them, the French infantry units deployed around Bazeilles suffered badly from their exposure to the deadly Prussian artillery. As the Prussian infantry pressed its attack, it suffered greatly from the deadly fire of the French infantry armed with the Chassepot rifles. Because of this, the Prussian casualties began to mount.

MacMahon rode forward at first light to observe the fighting at La Moncelle, suffered a serious wound in his left leg that temporarily rendered him unconscious. When MacMahon came around, he turned over command of the Army of Chalons to Ducrot, even though the latter was junior in rank to both Wimpffen and Douay.

As more German units began arriving on the battlefield, Ducrot became increasingly convinced that the French position at Sedan was untenable. He issued orders for the French army to pull back to Plateau d’Illy in preparation for a general withdrawal 10 miles to Mezieres. He began moving back those brigades that were not already engaged.

Ducrot’s elevation to army commander, however, did not last long. Apprised of Ducrot’s promotion, Wimpffen presented to Ducrot his letter from Montauban. Ducrot immediately submitted to Wimpffen’s authority. Wimpffen’s first act was to override Ducrot’s order to withdraw. Wimpffen believed that the situation at Bazeilles was stable and that there still was an opportunity to punch a hole in the Prussian line that would enable the French army to reach Carignan in order to join forces with Bazaine at Metz.

The real situation was far from stable. Despite determined French counterattacks, Daigny fell to the Prussians at 10 a.m. The Saxons, who were now being reinforced by the IV Corps of Crown Prince Albert’s Fourth Army, put heavy pressure on the French at La Moncelle. The Bavarians succeeded in capturing Bazeilles an hour later following a hard fight for the Villa Beurmann. The Prussians mopped up in the village by firing their artillery at point-blank range against pockets of resistance by the stubborn French marines.

Enraged by heavy casualties in fighting for Bazeilles, some of the Bavarian infantry massacred several groups of French Marines who tried to surrender. Bavarian officers quickly intervened to prevent any further atrocities. Some of the French citizens in Bazeilles who had fought to protect their homes also were executed. The vengeful Bavarians torched a number of French houses in Bazeilles. The Bavarians essentially destroyed the village. Only a handful of homes escaped the conflagration. Although Wimpffen ordered Lebrun to retake Bazeilles, German artillery shattered the French counterattacks.

Prince August of Wurttemberg’s Guards Corps of the Prussian Fourth Army hurried into action following the sound of the cannon. While one of the Guard troops assisted in the fighting at Givonne, the Second Guard Division pushed west to link up with the Third Army. Meanwhile, the artillery of the Prussian Guard Corps exchanged fire with the artillery of Ducrot’s I Corps. It was an unfair fight, though. Outgunned by the superior range and accuracy of the Prussian guns, the French withdrew any guns that had not been knocked out.

In a desperate bid to keep the Prussian artillery at bay, the French committed a large number of skirmishers to cover the deployment of 10 guns at Givonne, but the Prussians captured the guns before the French artillerymen were able to unlimber them. At that point, the Prussians began shelling in the Bois de la Garenne.

The Prussians captured Givonne at 10 a.m. The majority of the French I Corps remained on the western slope of the Givonne valley where it suffered under the punishing enemy artillery fire. After being pounded for two hours by the Prussians guns, more French troops entered the Bois de la Garenne in the hope of escaping the German storm of iron.

The Bavarians and Saxons, with the continued support of the Prussian Fourth Corps, advanced from Bazeilles and Moncelle. Despite some strong resistance from the French, these German forces succeeded in dislodging the French from their positions east of Balan back to the Givonne ravine. Next, the Bavarians launched an assault on the village of Balan. They quickly captured the lightly held village, although a bloody fight occurred at a chateau situated on the west end of the village.

Shortly after noon the lead battalion of the Bavarians came to within a rifle shot of the old fortress of Sedan. At that point, a firefight erupted in the Givonne ravine between the Bavarians and the French. Reinforced by artillery and mitrailleuses, the French launched a spirited counterattack at 1 p.m. in which they succeeded in forcing back a Bavarian brigade, however, another Bavarian brigade quickly came up in support to recover the lost ground. The desperate fighting in that sector continued unabated for another hour.

Two French divisions advanced at 3 p.m. from the Givonne ravine against the 23rd Saxon Division. Assisted by the left wing of the Guard corps and Guard artillery, however, the Saxons halted the attack. “The energy of the French appeared to be by this time exhausted, for they allowed themselves to be taken prisoners by hundreds,” wrote Moltke. Repulsing the French attack, the Germans brought up more batteries. By mid-afternoon the Prussians had 21 batteries in action on a line that stretched from Bazeilles to Haybes.

On the west side of the battlefield, the Prussian V and XI corps of Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm’s Third Army, together with the Wurttemberg Division of the Wurttemberg-Baden Corps, crossed the Meuse at Donchery, as well as by several pontoon bridges downstream. In the meantime, Prussian cavalry patrols penetrated as far as the road leading to Mezieres, but they reported no sign of the French withdrawing in that direction.

Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm ordered the Prussian units that already reached the Mezieres Road to turn east and strike Douay’s VII Corps on the morning of September 2. By mid-morning, the Prussians had captured the village of Saint-Menges. At the same time, two Prussian infantry companies secured a foothold in the village of Floing.

The Prussians unlimbered three artillery batteries at Saint-Menges. The French had eight batteries at Floing with which to engage the enemy batteries at Saint-Menges. To even the artillery contest, the Prussians sent additional batteries to reinforce those already engaged at that location.

The Prussians soon had six batteries, totaling 72 guns, in action. With their greater range and accuracy, the Krupp guns turned the tide. The Prussian gunners systematically silenced all of the French guns. But when the Prussians began to advance their batteries, they came under devastating fire from French mitrailleuse gunners who mowed down the crews of the forward-most Prussian guns.

Wimpffen initially believed the Prussian advance from the northwest was a mere demonstration. By midday, though, he realized that the Prussians were conducting a major assault, so he dispatched two divisions from the I Corps to support Douay. Wimpffen also parceled out brigades from De Failly’s V Corps to support sectors that appeared weak or in danger of being overrun by the Prussians.

In the early afternoon, under the cover of the Krupp guns, a brigade from Prussian XI Corps used the cover of a ravine to strike Douay’s left flank between Floing and the Meuse River. This well-conceived tactic enabled the Prussians to seize the high ground overlooking Floing.

General Jean Margueritte’s French First Reserve Cavalry Division, composed of light cavalry, occupied a position behind Douay’s VII Corps at Calvaire d’Illy. As the Prussians continued their advance northeast toward the apex of the French defensive positions, Ducrot ordered Margueritte to attack the units of the Prussian left wing that were approaching Illy, as well as charge the Prussian guns at Saint-Menges.

As Margueritte rode forward to observe the ground over which his squadrons were about to charge, a bullet tore through both of his cheeks. Badly wounded, Margueritte turned over command of his division to General Gaston Gallifet.

The Light Cavalry Division was composed of three regiments of Chasseurs d’Afrique, one of French Chasseurs, and one of hussars. Gallifet deployed his horsemen in three lines. They advanced at a trot towards the enemy.

“The advance was over very treacherous ground, and even before the actual charge was delivered the cohesion of the ranks was broken by the heavy flanking fire of the Prussian batteries,” wrote Moltke of Gallifet’s charge. “With thinned ranks but with unflinching resolution, the individual squadrons charged the troops of the 43rd Infantry Brigade, partly lying in cover, partly standing out on the bare slope in swarms and groups, [as well as] the reinforcements hurrying from Fleigneux.”

Moltke noted that the first line of the former was pierced at several points, and that a band of the intrepid troopers dashed from Casal through the intervals with eight artillery pieces blazing at them with case-shot, but the companies beyond stopped their further progress. Other detachments cut their way through the infantry as far as the narrow pass of St. Albert where they were met by the battalions debouching from the pass, he said.

“These attacks were repeated by the French again and again in the shape of detached fights, and the murderous turmoil lasted for half an hour with steadily diminishing fortune for the French,” continued Moltke. “The volleys of the German infantry delivered steadily at a short range strewed the whole field with dead and wounded horsemen.”

Many of the French horsemen fell into the quarries or down the steep declivities, while others escaped by swimming the Meuse. Slightly more than half of these brave troops returned to the protection of the forest. Of the 2,408 men in Margueritte’s division on the morning of September 1, just 1,327 remained in ranks the next day.

Douay’s soldiers followed up with an attack to clear the Prussians from Floing, but after an hour of intense fighting Prussian reinforcements arrived to check their attack. But on the rest of the battlefield, French soldiers firing the deadly Chassepot rifle stopped the Prussians cold. When the soldiers of the Prussian XI Corps arrived at Fleigneuz, they were able to shake hands with members of the Prussian Guard at Olly. The meeting of the two units completed the Prussian encirclement of the French.

For two hours beginning at Noon, the French continued to fight in the vicinity of Calvaire d’Illy. As Ducrot’s I Corps pulled back, it exposed the right flank of Douay’s VII Corps. The Third Division of the French V Corps was sent to plug the gap, but it dissolved when it encountered devastating enemy fire. So many of its soldiers quit the ranks to seek the shelter of the woods that only one brigade remained in action. Prussian guns silenced any French battery that went into action. The French troops holding the Calvaire d’Illy, relinquished control of it to the Prussians at 2 p.m. and withdrew to the Bois de la Garenne.

At that point, the road leading to the Belgian border became a jumble of fleeing French soldiers, civilians, and wagons. Sarazin observed civilians fleeing together with the soldiers, “These poor folk were dragging their weeping children along with them and were carrying off, on carts or wheelbarrows, everything they had been able to throw together in haste,” he wrote.

Moltke cataloged the Prussian successes. “The 87th Regiment seized eight guns which were in action, and captured 30 baggage wagons with their teams, as well as hundreds of cavalry horses wandering riderless,” wrote Moltke. “The cavalry of the advanced guard of the Vth Corps also made prisoners of General Jean Auguste Brahaut [the commander of the cavalry division of the V Corps] and his staff, besides a great number of dispersed infantrymen and 150 draught-horses, together with 40 ammunition and baggage wagons.”

By that point in time, the Prussian artillery had been fully deployed. Von Moltke began tightening the ring of steel around the French from east and west. Prussian artillery hammered the French I and VII corps from front and rear. French soldiers tried to seek shelter from the relentless bombardment in the Bois de la Givonne, but the artillery pummeled them even in the woods.

With disordered French divisions milling around in the Bois de la Garenne, Prince Kraft of Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen, the commander of the Prussian Guard artillery, directed his gunners to shell the woods at 2 p.m. “Our superiority over the enemy was so overwhelming that we [the artillery] suffered no loss at all,” he wrote. “The batteries fired as if at practice.”

Under the relentless pounding of the Prussian artillery, what little order and morale remained in the French units in the woods evaporated. “Cannon boomed everywhere,” wrote French Lieutenant Louis de Narcy. “The earth was ploughed up, trees splintered. From clearings in the woods we could make out clouds of fire and smoke in an arc all around us.” He estimated that the Prussians had arrayed 600 cannon against the French.

At midafternoon the Prussian XI Corps entered the Bois de la Garenne. Despite knots of French soldiers still resisting, the Prussians scooped up thousands of prisoners. The woods were a charnel of slaughtered men and animals. “The picture of destruction I beheld [in] the Bois de la Garenne surpassed all the horrors that had ever met my gaze, even on the battlefield,” wrote young Lieutenant Paul von Hindenburg, the future German field marshal and statesman.

The Germans were within reach of Sedan by late afternoon, but were kept at bay by French guns firing from the old fortress. But there was no further need for the German infantry to advance. As the French positions continued to shrink, the tempo of German artillery escalated. Disordered masses of men, horses and wagons rushed from the woods to the deceptive shelter of Sedan where French officers attempted to rally their men inside the fortress to no avail.

King Wilhelm watched the events with Moltke, Bismarck, and a number of minor German princes. The group observed the battle from the heights at La Marfee south of the river. Rumors that Napoleon III was in Sedan had reached Wilhelm and his staff, but they initially disregarded the rumors. “The old fox is too cunning to be caught in such a trap,” said Bismarck to Sheridan. “He has doubtless slipped off to Paris.”

Napoleon III, a passive observer in the Sedan fortress throughout the afternoon, had received a message from Wimpffen at 2 p.m. stating his intent to break out to the southeast and imploring Napoleon to capitulate. “Let Your Majesty come and place himself amid his troops, who will consider it an honour to open a passage for him,” wrote Wimpffen. Realizing that the battle was lost, Napoleon III began to seriously contemplate surrendering to the Prussians.

But Wimpffen still had a lot of fight in him. Believing that the breakout to Carignan was still possible, he sent orders to Douay to act as the rear guard. Douay replied that his own line was barely holding. Receiving no further help, Wimpffen organized some troops around the old camp near Sedan, composed of several Marine units and one brigade from the V Corps and sent them against the Bavarians at Balan. The French counterattack pushed the Bavarians to the southern edge of the village where some French civilians joined in the fighting.

While Wimpffen was fighting for Balan, at midafternoon Napoleon III ordered a white flag to be raised above Sedan, and he instructed Ducrot to prepare a general order for ceasefire to be issued to the French units. Ducrot demurred on the matter, insisting that such an order was Wimpffen’s responsibility. But Wimpffen was at Balan, and therefore was unavailable to consult on the matter. The stubborn commandant of the Sedan fortress tore down the first white flag, claiming that he only took orders from Wimpffen.

The Prussians eventually checked Wimpffen’s advance and then steadily drove back his troops. As Wimpffen rode to Sedan to look for reinforcements in the late afternoon, he encountered the emperor’s emissary to the Prussians. The emissary instructed Wimpffen to cease fire because negotiations with the Prussians were about to begin. Wimpffen refused and continued looking for any unit still intact. He cobbled together 2,000 men still under arms. He hurled them at Balan again, but the Bavarians shredded their attack. After the attack was repulsed, Wimpffen gave up all hope of breaking through the Prussian encirclement and returned to Sedan.

The majority of the Prussian artillery batteries had directed their fire in the late afternoon on the fortress of Sedan. The deadly shells killed soldiers and civilians alike. The civilians sought shelter in cellars as burning buildings collapsed around them. Another French white flag went up in the area of the southwest Torcy suburb, and the German fire gradually died down when it became evident the French were beaten.

King Wilhelm’s staff officer, Lieutenant Paul von Schellendorff rode to Sedan with a demand for the French surrender. To his surprise, French staff officers took him to their emperor. Napoleon III, looking tired and dejected, had one of his officers, General Honore Charles Reille, accompany Von Schellendorff with a letter to King Wilhelm.

At 6:30 p.m. the two officers reached the king. Reille presented him with a note from Napoleon III. “Having been unable to die amidst my troops, it only remains for me to place my sword in your Majesty’s hands,” wrote the French emperor.

“Regretting the circumstances in which we meet, I accept Your Majesty’s sword, and invite you to nominate one of your officers invested with full powers to negotiate the capitulation of your army, which has fought so bravely under your orders,” replied King Wilhelm. “For my part, I have designated General Moltke for this purpose.”

The two sides subsequently held surrender negotiations that night at Donchery with Wimpffen representing the French and Moltke and Bismarck for the Germans. Wimpffen requested the French army to be allowed to march out with their arms and flags, under oath to sit out the rest of the war. Moltke and Bismarck categorically refused stating that they would accept nothing short of an unconditional surrender from the French. Wimpffen broke off negotiations, declaring that the French will continue to fight. He was given until 9 a.m. on September 2 before the Germans would open fire again.

Wimpffen returned to Sedan to debrief the emperor on the progress of the surrender negotiations. At that point, Napoleon III decided to make an appeal in person. He met with Bismarck in Donchery at 6 a.m. where the chancellor politely yet firmly rejected his entreaty for an honorable surrender. Given that the French army was in no state to continue the struggle, the emperor directed Wimpffen to agree to the Prussian terms. A crestfallen Wimpffen signed a document containing an unconditional surrender five hours later.

The Prussians inflicted a catastrophic defeat on the French at Sedan. The French lost 3,000 dead and 14,000 wounded and 104,000 captured. Another 8,000 French soldiers had fled across the border into Belgium where the Belgians, in keeping with their agreement with the Prussians, confined the French soldiers for the duration of the war.

The Germans lost 2,320 killed, 5,980 wounded, and 700 missing. The Bavarians bore the brunt of the Prussian losses. While Prussian artillery inflicted the majority of the losses incurred by the French, French soldiers armed with the deadly Chassepot rifle inflicted the bulk of the casualties suffered by the Germans.

Although the French soldiers marched off to prisoner-of-war camps under heavy guard, the Prussians bundled off Napoleon III to comfortable captivity at the Wilhelmshohe Castle in Hesse. Seven months later they allowed him to depart for England where he remained in exile for the rest of his days. The deposed French emperor subsequently passed away at the age of 64 on January 9, 1873, in a surburb of London. Napoleon III had the dubious distinction of being the first French president and the last French emperor.

Following the collapse of Napoleon III’s government, members of the National Assembly formed a provisional Government of National Defense. With MacMahon’s army taken off the board, the Prussian Third and Fourth armies rushed to Paris, closing the ring around the French capital on September 15. With Paris besieged and no possibility of relief, Bazaine surrendered his army at Metz on October 29, 1870. After a valiant, but futile resistance, Paris also surrendered on January 28, 1871.

Even before Paris surrendered, Wilhelm I was proclaimed the German emperor. The Prussians combined the North German Confederation and Bavaria, Baden, Saxony, and Wurttemberg into the newly established German Empire. Bismarck had finally achieved his dream of a unified Germany.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments