By Mike Phifer

“Lee’s army is really whipped,” declared Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck on May 26, 1864. “The prisoners we now take show it, and the actions of his army show it unmistakably. A battle with them outside of entrenchments cannot be had.” Thwarted by the Army of Northern Virginia at the North Anna River, Grant was preparing to swing around Robert E. Lee’s right flank again and push southeast. Lee then would have no choice but to leave his entrenchments at North Anna and attempt to stop the Federal forces from reaching Richmond, probably along the Chickahominy River. Believing the fight had gone out of Lee’s army, Grant added, “I feel that our success over Lee’s army is already insured.” He would quickly discover that he had spoken too soon.

Almost a month earlier, Maj. Gen. George Meade, operational commander of the Army of the Potomac, had initiated the Overland Campaign with some 118,000 troops. Then came, in swift succession, the Battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse, and North Anna, which cost the Union Army an appalling 40,000 casualties. Meade needed reinforcements not only to replace his casualties, but also the many valuable veterans whose three-year enlistments were about to expire at the end of June. Grant, as general-in-chief of all Union forces in the East, petitioned Washington for more men. President Abraham Lincoln sent him 33,000 garrison troops belonging mostly to heavy artillery regiments with no combat experience. At the same time, Grant recalled the XVIII Corps under Maj. Gen. William Smith and other troops that could be spared from Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler’s Army of the James, currently bottled up on the Virginia Peninsula at Bermuda Hundred, southeast of Richmond.

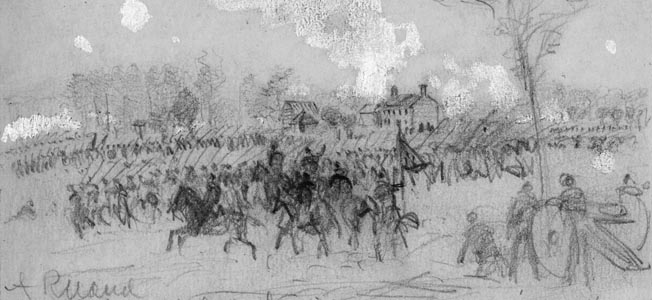

On the evening of May 26, the Federal army started to move. Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan led two of his cavalry divisions southeast to seize a crossing over the Pamunkey River at Hanovertown. Behind them marched Brig. Gen. David Russell’s infantry division from Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright’s VI Corps. Sending out pickets to cover their withdrawal, the four remaining corps of bluecoats slipped across the North Anna River in the rain and darkness on pontoon bridges. The maneuver went without a hitch, although Confederate pickets “made things lively” for Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps as it withdrew.

With the Army of the Potomac safely back across the North Anna, the tired Federals began to tramp southeast behind Sheridan in two columns on muddy roads. Bringing up the rear was a cavalry division under Brig. Gen. James Wilson, which had been creating a diversion on Lee’s left flank. Meanwhile, horse soldiers of Brig. Gen. George Custer’s brigade of Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbert’s division had reached Dabney Ferry, near Hanovertown, in the foggy early morning hours of the 27th. Sheridan, who was riding with Torbert and Custer, wanted both banks of the river immediately secured so that the 50th New York Engineers could throw two pontoon bridges across the fast-moving, murky water.

The engineers’ task suddenly became more difficult when a detachment of the 5th North Carolina Cavalry opened up from the other side of the river. The troopers of 5th Michigan Cavalry quickly returned fire with their repeating carbines, driving off the Tarheels. The engineers heaved two pontoon boats into the water, and a company of cavalrymen climbed into them and quickly rowed to the other side of the river under covering fire to establish a bridgehead, allowing the engineers to get a bridge across the river. Once the first bridge was complete, the rest of Torbert’s division pounded across, riding hard toward Hanovertown while the engineers began work on a second bridge a few yards upriver.

At 6 am, Lee received reports that Federal cavalry had crossed at Dabney Ferry. It was now clear that Grant was again maneuvering around Lee’s right flank. Lee wasted no time in getting his recently reinforced army moving 15 miles southeast to Altee’s Station. In the last month alone, the Army of Northern Virginia had suffered a staggering 25,500 casualties, roughly 40 percent of Lee’s army. Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge had brought his division from the Shenandoah Valley after defeating the Federals at New Market to reinforce Lee, while Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s division arrived after Butler was bottled up at Bermuda Hundred. These new troops plus others Lee managed to scrape together brought his strength back up to 64,000 men.

By that afternoon, lead elements of Lee’s army approached Altee’s Station, where they soon would be joined by the rest of the army. That same day the Army of North Virginia lost Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell, the II Corps commander, who took emergency medical leave due to dysentery that was also affecting Lee. Maj. Gen. Jubal Early took his place. The bulk of the Federal army, meanwhile, went into camp a few miles from Dabney Ferry and Nelson’s Bridge, where the ever industrious engineers would soon be building more pontoon bridges early the next day.

On the morning of the 28th, the Confederates resumed marching toward Totopotomoy Creek, where Lee intended to take up a new defensive position. The bluecoats, meanwhile, began to cross the Pamunkey while two divisions of Sheridan’s cavalry covered their rear and the remaining division under Brig. Gen. David Gregg proceeded to a crossroads named Haw’s Shop to make a reconnaissance. There the Federals bumped headfirst into Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton and 4,500 Confederate cavalrymen around mid-morning. Gregg quickly dismounted his men and dug in west of Haw’s Shop. Hampton also dismounted half his men and quickly constructed breastworks out of fence rails and logs on a ridge a few hundred yards west of the Federals. For the next six hours the two forces blazed away at each other across the fields and woods. At 4 pm, Custer’s brigade arrived on the battlefield and launched a dismounted attack in two lines.

On the northern flank of the battlefield, a Confederate scout mistook dismounted friendly cavalrymen for Federal infantry, which led Hampton to fear that he was being cut off. He ordered a withdrawal that Custer’s men quickly exploited, overrunning the 20th Georgia Battalion. Most of Hampton’s force escaped, having suffered 378 casualties, and retreated toward Totopotomoy Creek with a number of prisoners. The Federal cavalry sustained 365 casualties.

By May 29, Meade’s army was firmly across the Pamunkey. Grant was still not sure where Lee was, but he thought he might be somewhere along Totopotomoy Creek. With Sheridan’s cavalry resting at Old Church after the fight at Haw’s Shop, Union infantry began probing for the enemy. Skirmishing broke out as the Federals pushed southwest toward the Army of Northern Virginia’s dug-in position along the south side of the creek. Early’s II Corps held the right of the Confederate line in the swampy woods near Totopotomoy Creek; Breckinridge held the center with Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill’s III Corps on the left and Lt. Gen. Richard Anderson’s I Corps positioned behind Early in reserve.

While Lee waited to see what the Federals would do, he met with General P.G.T. Beauregard in an attempt to obtain more troops but initially was disappointed. Beauregard could spare none. “If General Grant advances tomorrow,” Lee telegraphed Confederate President Jefferson Davis that evening, “I will engage him with my present force.” It was less a threat than a simple statement of fact.

The next day the Federal army moved toward Lee’s position. Skirmishing and artillery fire broke out as Hancock’s corps overran some of Breckinridge’s advanced rifle pits. Wright’s corps, operating against Hill on the enemy’s left flank, became bogged down in swampy terrain near Crump’s Creek. Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps, pressing against Early, waded Totopotomoy Creek and began probing along Shady Grove Road. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside was ordered to move his IX Corps between Hancock and Warren.

Seeing an opportunity to strike Warren, Lee ordered Early to attack. Early sent Maj. Gens. Robert Rodes’ and Stephen Ramseur’s divisions forward along the Old Church Road, while Maj. Gen. John Gordon’s division was held in reserve. From there, Early’s men followed the road east, crashing into Colonel Martin Hardin’s brigade of Brig. Gen. Samuel Crawford’s division. The rest of the division had taken up position at Bethesda Church. Hardin’s brigade broke and ran hard for Crawford’s position with the Confederates screeching after them. Crawford’s division quickly gave way as well, retreating north to Shady Grove Road. By this time, the Confederate attack had stalled. Rodes attempted to reorganize his men, losing valuable time, while Ramseur moved his division into position to lead the attack. Anderson, whom Early had instructed to attack Warren from the west, unaccountably did nothing.

Warren wasted no time in repositioning his infantry and artillery to deal with Early’s attack from the south. When Ramseur’s men finally charged forward “with reckless daring,” they were met with deadly artillery fire from the 1st New York Light Artillery, ending the attack. Early withdrew, suffering 1,200 casualties and blaming Anderson—with some justification—for failing to help. Warren suffered 750 killed and wounded.

Colonel Thomas Devin’s cavalry brigade from Torbert’s division galloped southwest from Old Church for Cold Harbor, a strategic crossroads 10 miles north of Richmond, in an attempt to cover Warren’s left flank. A brigade of South Carolinians under Brig. Gen. Mathew Butler collided with the Union horsemen along Matadequin Creek. Butler’s men drove in Devin’s pickets, but Custer’s and Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt’s brigades soon arrived. The Federal troopers, aided by horse artillery, managed to flank Butler’s men and drove them back to within 1½ miles of Cold Harbor.

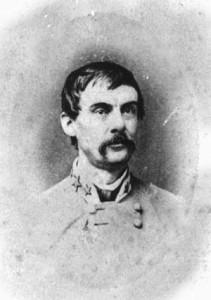

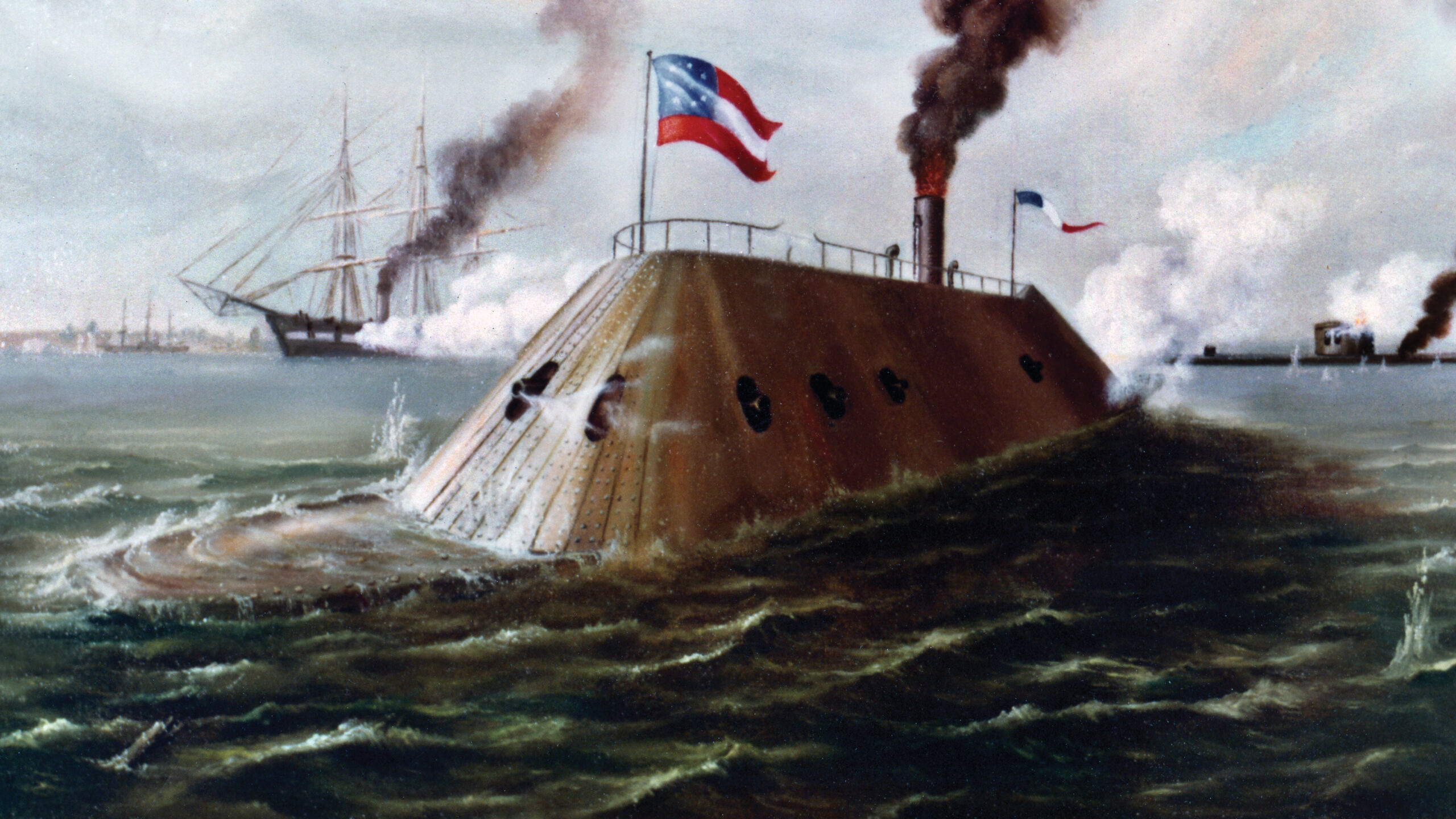

Lee was becoming greatly concerned about his right flank, with the Federal cavalry probing toward the crossroads of Cold Harbor, where one road led north threatening the Army of Northern Virginia’s rear, another led indirectly to Richmond, and three more snaked south to Petersburg and White House Landing. Adding to Lee’s concern were reports that Smith’s XVIII Corps, with 16,000 fresh bluecoats, was on the way to join Grant at Cold Harbor. At 11 pm, Lee finally received some good news when he learned that Maj. Gen. Robert Hoke, with 6,800 much needed reinforcements, had been dispatched from Beauregard “with all possible expedition” to reinforce him. They could not get there a moment too soon.

Brigadier General Thomas Clingman’s brigade, the first element of Hoke’s division to leave Richmond, arrived by train in the early morning of May 31 and was directed to march to Cold Harbor via Mechanicsville and Gaines’s Mill. More trains carrying the rest of Hoke’s division headed out at 9 am. Around noon, Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee rode into Cold Harbor with his cavalry division to relieve Butler and hold the crossroads until Hoke arrived. Meade’s infantry, meanwhile, continued to skirmish with the Confederates at Totopotomoy Creek, but no direct assault was launched at the formidable enemy entrenchments. Concerned that the Confederate cavalry planned a counterattack, Torbert and Custer, with Sheridan’s approval, decided to strike first at Cold Harbor.

In midafternoon the Federal cavalry attacked, and Fitzhugh Lee sent an urgent message to his uncle, Robert E. Lee, telling him that he was going to dispute the Federals’ progress and mentioning that Clingman’s brigade was only a few miles away resting. “Had they not be better ordered on to assist in securing this place?” Fitzhugh Lee wondered. Positioned behind fence rail barricades and log breastworks, his men could use all the help they could get when the Federal cavalry attacked. Clingman finally arrived and took up position on Fitzhugh Lee’s left.

The Confederates continued to hold out until Torbert decided to flank their position. While Custer held the defenders in place, Merritt hit the Confederates’ left flank. Elements of Custer’s command and Devin’s men on Fitzhugh Lee’s right struck as well. The Southern forces gave way and retreated a mile to the west, where they dug in on a low ridge soon to be reinforced with the rest of Hoke’s division. The Federals now held Cold Harbor.

Earlier in the day, Lee had ordered Anderson’s corps to pull out of its position at Totopotomoy Creek and head south to the crossroads. This movement was soon detected by the Federals. At Cold Harbor, Sheridan was becoming concerned with Torbert’s exposed position. “I do not feel able to hold this place,” he reported to Meade. Sheridan ordered Torbert to evacuate Cold Harbor after dark, but orders arrived from Meade to hold on to “Cold Harbor at all hazards.” Wright’s VI Corps, said Meade, was ordered south and should relieve them in the morning. Meanwhile, Smith’s XVIII Corps was ordered to Cold Harbor as well, but a mixup in orders sent Smith marching toward New Castle Ferry instead. The Federal horsemen began strengthening the existing works and throwing up new ones along the road north to Beulah Church.

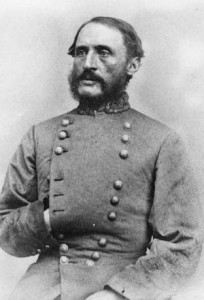

Wright’s corps did not reach the Union troopers first on the morning of June 1. Instead, shortly after sunrise, Maj. Gen. Joseph Kershaw of Anderson’s I Corps advanced toward Beulah Church, intending to attack the Union cavalry. Leading Kershaw’s attack was his old brigade, now commanded by Colonel Lawrence Keitt. South of them, Hoke was expected to attack the enemy with his division, but due to a misunderstanding he never left his entrenchment.

Keitt, mounted on a gray horse, led his brigade across open ground toward Beulah Church Road, where Union troopers waited behind their breastworks. Leading the charge with a Rebel yell was the 20th South Carolina. A point-blank sheet of musket fire erupted from the Federal line; horse artillery blasted the attackers as well. Keitt was shot from the saddle, and the regiment broke. A second charge was abruptly halted by a renewed torrent of fire. Kershaw ordered no more attacks. His division fell back to the left of Hoke, separated by a ravine and a waterway called Bloody Run. The Confederate line near Cold Harbor began taking shape.

Around 9 am, elements of Wright’s corps finally arrived after a grueling march and took over the defense of Cold Harbor. As the rest of the corps arrived throughout the day, the bluecoats extended the works to the north and south. After getting its orders straightened out, Smith’s corps marched under a burning sun to take up position to the right of Wright’s sweltering men. Orders were issued to Hancock to pull his corps out of line after dark and move south. Initially, Grant had moved troops to Cold Harbor to counter Lee’s shifting of troops there, but now with two full corps there or on their way Grant began to think offensively. “The enemy have not long been in position about Cold Harbor,” Meade explained to Smith, “and it is quite important to dislodge, and, if possible rout him before he can entrench himself.” They would have to hurry—the Confederates were quickly digging in.

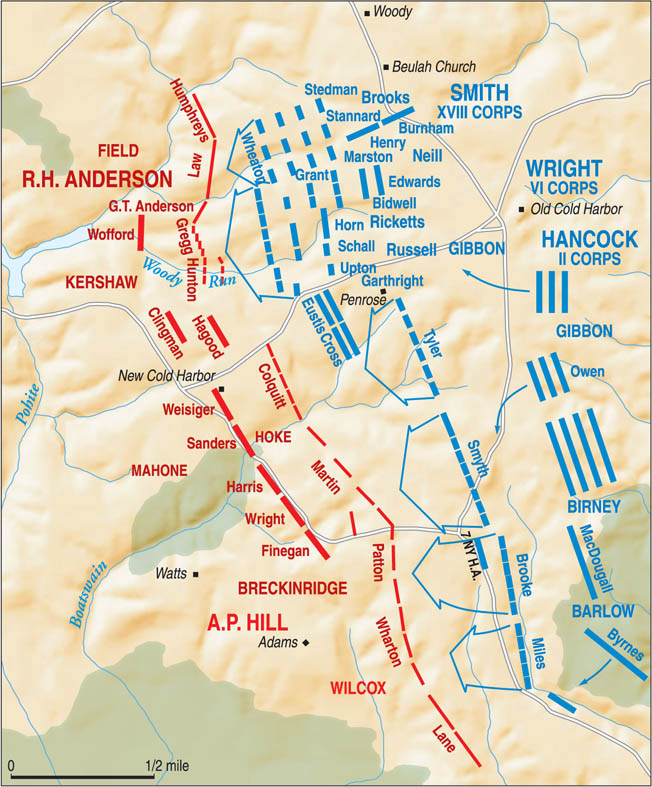

At 6:30 pm, four divisions from Wright’s and Smith’s corps, some 20,000 men in all, advanced toward roughly 10,000 troops of Hoke’s and Kershaw’s divisions sheltered behind earthworks. Two other Union divisions remained behind to protect the flanks. The attacking Federals south of the Cold Harbor Road were raked with canister and musketry well before they could reach the Confederate entrenchments. They stalled.

North of the road, artillery and small arms fire also hammered the advancing Federals, inflicting numerous casualties. Colonel Elisha Kellogg, leading his 1,500-man 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery from Brig. Gen. Emory Upton’s 2nd Brigade, was determined to earn his novice troops a reputation as a fighting regiment. Kellogg’s “Heavies” rushed across the open field and past the abandoned skirmishers’ rifle pits toward the main entrenchment held by Clingman’s men. There they found an impassable abatis of interweaved pine saplings. Kellogg led his men through a narrow channel in the brush, only to be greeted by a sheet of flame bursting from the Confederate breastworks that literally burned the men’s faces. “A sheet of flame, sudden as lightning, red as blood, and so near it seemed to singe the men’s faces, burst along the Rebel breastworks,” recalled Adjutant Theodore Vaill. “The shrieks and howls of almost 250 men rose above the yells of triumphant Rebels and the roar of their musketry.” A watching New Yorker thought, “Had hell been turned up sideways, the sight could not have been more fiery.”

The regiment hit the ground. A second volley was high, but brutal fire from their left inflicted heavy casualties. “About face!” shouted Kellogg, who was hit three or four times by bullets and fell dead across the abatis. The men, blinded by the smoke, staggered in every direction. Some were shot down at the breastworks; others were captured. Upton arrived on the scene and ordered the survivors to lie down. Dismounting from his panicky horse, Upton took shelter behind a tree, firing round after round from muskets loaded and passed up to him from his aides.

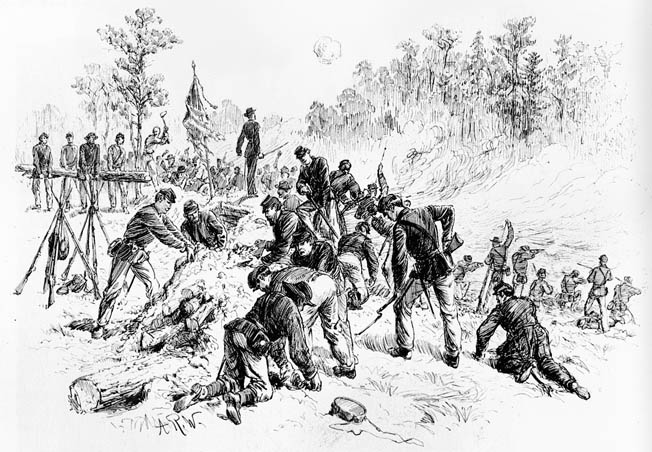

To the right of Upton’s brigade the Federals had a better time of it. Colonel William Truex’s brigade from Brig. Gen. James Ricketts’ division pushed through lightly held works into the ravine between Clingman and Brig. Gen. William Wofford’s brigade of Kershaw’s division. Joining them was Colonel Benjamin Smith’s brigade. Splashing through the mud and knee-deep marsh, the Federals from Truex’s brigade attacked the 8th North Carolina of Clingman’s brigade in the front, flank, and rear. The Confederates broke and ran, causing two of Clingman’s other regiments to collapse and fall back as well.

To the right of Truex and Smith’s brigades, Colonel Jeremiah Drake’s XVIII Corps brigade endured heavy fire from the main Confederate line and was forced to dig in and wait for help. It soon came in the form of Colonel William Barton’s brigade, which moved forward and hit the enemy line held by Wofford’s troops. Drake, waving his sword above his head, cried, “See those devils run!” and led a handful of men into the entrenchments. There he was shot down and the surviving members taken prisoner. Under attack from the flank and rear by Federals advancing from the ravine, Wofford’s brigade broke and fled to the rear at breakneck speed. A half-mile gap now appeared in the Confederate line.

Confederate reinforcements quickly rushed in to reinforce Clingman and retake the section of the works lost by Wofford. Darkness was falling as brutal fighting drove the Federals from the works and pushed them out of the ravine. Overall, the VI and XVIII Corps’ attack had cost them about 2,200 casualties, but the men were now closer to the main Confederate entrenchment. Meade ordered another attack the next day, this time to be reinforced by Hancock’s corps, which was ordered to take up position to the left of Wright and join the attack.

By 8:30 pm, Hancock began pulling his divisions out of line for their march south. The men tramped through the hot, breathless night made worse by suffocating clouds of dust and smoke. The march became a comedy of errors. “By some blunder we got on the wrong road,” remembered John S. Jones of the 4th Ohio. “We became entangled in the woods; the artillery and infantry got mixed up in unutterable confusion; the heat was oppressive; the sand shoe-mouth deep; the air thick with choking dust, and we did not reach Cold Harbor until late on the morning of June 2. We were in a condition of utter physical exhaustion.” Seeing the shape Hancock’s men were in, Meade postponed the morning attack until 5 pm.

When word reached Lee that Hancock was pulling out of line, the Confederate commander ordered Breckinridge to move south as well. By mid-morning of June 2, two divisions from Hill’s corps were marching south to join them. After some delay, Breckinridge arrived and extended the Confederate line south to Turkey Hill, driving off a small Federal force and digging in. The Confederate line was now anchored on Chickahominy Creek to the south and Totopotomoy Creek to the north.

Early acted swiftly on Lee’s orders “to get upon the enemy’s right flank” and drive them, falling on Burnside’s forces around Bethesda Church. “The field was a mass of yelling shrieking demons wild with pain, thirst, anger and excitement,” a Confederate officer remembered years later. Three divisions attacked Burnside’s flanks, enduring heavy artillery fire and bending his corps and part of Warren’s corps back about half a mile from the church.

Grant decided to postpone the next attack until 4:30 am on June 3 to give Hancock’s men more time to rest. The Confederates took advantage of the delay by strengthening their seven miles of entrenchments to provide interlocking fields of fire. Behind the breastworks on the Confederate right were men of Hoke’s division, Breckinridge’s division, and Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s and Maj. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s divisions of Hill’s III Corps. Anderson’s I Corps held the center, while Early’s II Corps and Hill’s remaining division under Maj. Gen. Henry Heth held the left flank. They looked down their muskets across an open killing ground.

Seeing the fortified Confederate position, one Federal officer noted, “It became a recognized fact amongst the men themselves that when the enemy had occupied a position six or eight hours ahead of us, it was useless to attempt to take it.” Nevertheless, Grant was determined to try, believing the Rebels’ morale was low. A successful assault, said Maj. Gen. Andrew Humphreys, Meade’s chief of staff, would give the Federals “the opportunity of inflicting severe loss upon Lee when falling back over the Chickahominy, as that must necessarily be attended to with some disorder of his troops.”

The Union troops, waiting through the day and night, were not so optimistic. Mostly, they were just tired. Drummer Delavan Miller of the 2nd New York Heavy Artillery recalled that “the men were so utterly worn out they would have willingly risked a wound for the sake of the rest it would give them.” Grant’s aide, Lt. Col. Horace Porter, would later claim that while he was carrying orders for the main assault the next morning he noticed that many of the soldiers were writing their names and home addresses on slips of paper and pinning them to the back of their coats in case they were killed. The makeshift name tags would enable them to be recognized and their families back home informed of their fate. It was not a good omen of things to come.

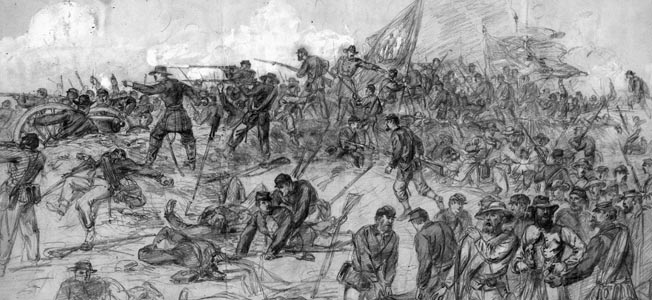

A refreshing rain stopped just before first light. The Federal troops were up and preparing to attack. Just before 4:30 am, skirmishers on the Union left slipped out of the mist, and the sporadic crack of rifle fire soon pierced the early morning air. A signal gun boomed, and bugler George Gracey sounded the advance. Hancock’s men moved forward with Brig. Gen. Francis Barlow’s division on the left and Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s division to their right. Behind them in support was Brig. Gen. David Birney’s division.

Moving out of the wood line and advancing quickly, screaming their typical attack cry, “Huzzah! Huzzah!” the Union troops advanced toward the shoulder-high enemy works, where they were greeted by a hailstorm of bullets and canister. The 7th New York Heavy Artillery of Colonel John Brooke’s brigade, crossing the open field through tall, wet grass, had great gaps blown into its lines. Still the Heavies pushed on, leaving bodies in their wake and taking shelter in a hollow in front of the enemy works. Colonel Lewis Morris, commander of the 7th New York, reformed his men and led them over the enemy works held by the 26th Virginia Battalion of Brig. Gen. John Echols’ brigade.

In the deadly churn of fighting, an officer and two men attempted to grab the 26th Virginia’s colors. The color bearer refused their demand to surrender and ran the flagstaff’s brass point through the Federal officer. The color bearer was promptly shot down, still clinging desperately to the flag. A melee ensued as more Confederates rushed forward to save it, but in the end the Federals captured the colors. Soon the Confederates began retreating or surrendering. One “rose up and fired into our color-guard, dropped his musket, threw up his hands and said ‘I surrender,’” remembered a soldier of the 7th Heavies. “The Color-sergeant thrust the steel lance on the color-staff into his open mouth, and, with a reference to his canine ancestry, said, ‘You spoke too late.’”

During the dash to the enemy works, Colonel Nelson Miles’ brigade was to the left of Brooke’s men. Enduring heavy fire from Brig. Gen. Gabriel Wharton’s brigade of Virginians, Miles’ men sought cover behind a road cut, while Colonel Charles Hagwood ordered his 5th New Hampshire to push on. They performed a half wheel to the right and scrambled over the enemy earthworks alongside the 7th New York Heavies. The New Hampshire boys pushed on to the McGehee House and fired on the enemy reserve line held by the 2nd Maryland Regiment from Breckinridge’s command.

The Marylanders charged forward, as did Brig. Gen. Joseph Finnegan‘s Florida brigade. Survivors of the broken 26th Virginia came rushing past them. Once the Virginians were out of the way, the Floridians and Marylanders slammed into the bluecoats, rooting them out of the McGehee House and the earthworks. Morris regrouped and attempted to retake the breastwork but was stopped cold by a murderous fire. “We fought like hell and got licked like damnation,” wrote Lieutenant Frederick Mather of the 7th New York.

To the right, Gibbon’s division advanced on a two-brigade front, with two more brigades behind it. It quickly came under heavy musketry, grape, and canister fire. No reconnaissance had been done before the attack, and the troops soon encountered a swampy wooded area, the headwaters of Boatswain Creek. Brig. Gen. Robert Tyler’s brigade, including the 1,600 men of the 8th New York Heavy Artillery, was split in two by the murky waters. Two battalions of the 8th New York Heavies were north of the swamp with their flank along the Cold Harbor Road. Brig. Gen. Alfred Colquitt’s brigade of Hoke’s division hammered the attackers as they struggled forward, but some of the Federals managed to get within 20 yards of the enemy breastworks before they were shot down. The rest sought cover. “Our artillery fired double-shotted canister at a distance of a hundred yards,” one Confederate gunner recounted. “At every discharge of our guns, heads, arms, legs, guns were seen flying high in the air. They closed the gaps in their lines as fast as we made them, and on they came, their lines swaying like great waves of the sea.”

On the southern side of the swamp, the remainder of the 8th New York Heavies and the 155th and 182nd New York regiments pushed through thick undergrowth, only to be hit with devastating fire themselves. Unable to advance or retreat in the deadly hailstorm of lead, the Heavies hugged the ground. Some loaded and fired, while others made makeshift cover from fence rails and dug desperately with bayonets, knives, and their bare hands to throw earth onto the rails. “It could not be called a battle. It was simply a butchery, lasting only ten minutes,” recalled a soldier from the 8th New York. The butchery may have lasted only 10 minutes, but the New Yorkers would be pinned down for the next 16 hours.

The other two New York regiments fared little better. Taking heavy casualties, they fell back 150 yards and dug in. “We felt it was murder, not war,” exclaimed one soldier, “or that at best a very serious mistake had been made.” On the left of Tyler’s brigade, the 164th New York dressed in its flashy Zouave uniforms fought its way to the breastworks held by the 17th North Carolina of Brig. Gen. James Martin’s brigade. The New Yorkers were driven back and their commander killed.

To the south of Tyler’s brigade, Colonel Thomas Smyth’s brigade advanced through some woods before reaching a clearing a few hundred yards away from Martin’s brigade. The veteran bluecoats came under murderous fire, and although some managed to struggle close to the enemy breastworks, most were forced to seek shelter and dig in 50 to 100 yards from their objective. Behind Tyler came Colonel Boyd McKeen’s brigade, packed in column formation. Casualties began to mount as it moved quickly across the open ground; McKeen himself was killed in the first rank. Colonel Frank Haskell took over but soon took a bullet in the head while ordering the men to lie down. In the rear and right of Smyth’s brigade was Brig. Gen. Joshua Owen’s brigade. Ordered by Gibbon to advance in column until he reached the Rebel entrenchment, Owen had other ideas. Upon reaching the swampy ground on the right of Smyth’s brigade, Owen swung his men southwest and came out on Smyth’s left flank and the right flank of the 7th New York Heavies. Coming under heavy fire, Owen’s men too dug in. Hancock’s corps would advance no farther.

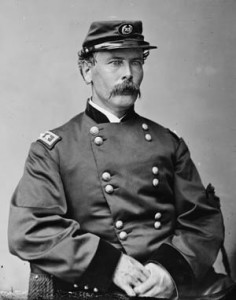

Wright’s corps, to Hancock’s right, was still holding the territory it had bought with blood two days earlier. Wright would make only limited attacks, feeling that it was suicidal to attempt any large-scale attack on the Rebel works. “It is simply an order to slaughter my best troops,” he said. Truex’s brigade, now commanded by Colonel John Schall, accompanied Smyth’s brigade in pushing into the swampy ground of Bloody Run before enemy fire forced it to dig in. Meanwhile, to its right, Brig. Gen. Thomas Neil’s division attacked in stacked brigades. Leading the way was Colonel Frank Wheaton’s brigade, which took a fearful hammering of small arms fire from the brigades of Brig. Gens. Tige Anderson and John Gregg. An artillery crossfire added to the Federals’ misery. To William Derby of the 27th Massachusetts, “The surface of the field seemed like a boiling cauldron from the incessant pattering of shot which raised the dirt in geysers and spitting sands.” Wheaton’s men fell back. The next brigade did not go any farther, and Neill’s attacked petered out.

The troops of Kershaw’s division and three brigades of Maj. Gen. Charles Fields’ division, both of Anderson’s corps, had a bloody surprise waiting for Smith’s men. Obscured by some woods, the Confederates had constructed a horseshoe-shaped work that could catch the Federals from three directions. At 4:30 am, Brig. Gen. William Brooks’ division on the left and Brig. Gen. John Martindale’s division on the right set off as ordered in a column of massed brigades. Smith hoped to use them as a battering ram.

Brook’s column, led by Brig. Gen. Gilman Marston’s brigade, advanced south of a wooded ravine, driving the Confederate pickets from their rifle pits and pushing heedlessly into the horseshoe, which immediately erupted in murderous fire. Marston would later report, “The ground was swept with canister and rifle-bullets until it was literally covered with the slain.” Smith, seeing the massacre, ordered Brooks to stop his men and have them seek shelter until the crossfire was over. Marston pulled back his men, and they began to construct entrenchments.

Meanwhile, Martindale’s division attacked on the north side of the ravine with bayonets fixed and rifles uncapped. Smith decided to split Martindale’s division by sending Brig. Gen. George Stannard’s brigade south into the ravine with orders to stay close to the southern edge, while Colonel Griffin Stedman pushed along the north side of the ravine. Alabamians of Brig. Gen. Evander Law’s brigade, standing two deep behind their works, hammered Stedman’s men, who “bent down as they went forward, as if trying, as they were, to breast a tempest,” remembered a bluecoat of the 12th New Hampshire. The tempest of lead killed or wounded files of men and brought the attack to a jarring halt. “To those exposed to the full force and fury of the dreadful storm of lead and iron that met the charging columns, it seemed more like a volcanic blast than a battle,” wrote Captain Asa Bartlett of the 12th New Hampshire.

To its south, Stannard’s brigade fared little better; Confederate artillery blew gaps in its line, and volleys of musketry swept away the remaining bluecoats. The Confederates behind the packed breastworks had to jostle for firing position, passing forward loaded muskets to those in front of them. “It was not war, it was murder,” said Law. The Union attack quickly ground to a halt, and the survivors limped back and dug in. In 10 minutes’ time more men had fallen than at any comparable time during the entire war. The XVIII Corps advance was over.

So, it soon became obvious, was the entire Union assault. “Men lay in places like hogs in a pen,” observed a Confederate soldier examining the carnage before him, “some side by side, across each other, some two deep, while others with their legs lying across the head and body of their dead comrades.” In less than an hour, about 3,500 bluecoats had become casualties. The rest had become less an army than a badly rattled group of disaster victims. “There was a helpless mob, a swarming multitude of confused men,” wrote a Confederate artillerist who witnessed the final assault. “They were falling by scores, hundreds. The mass was simply melting away under the fury of our fire.”

Despite a premature report from Hancock that the enemy works had been pierced by Barlow’s brigade, the II Corps commander reported to Meade at 5:30 am that Barlow had pulled back. Half an hour later, Hancock was reporting that his men were “close to the enemy” but unable to take their works. He added his opinion “that if the first dash in an assault fails other attempts are not apt to succeed better.” Meade ordered Hancock to attack again, but he dug in instead. Any new attack would be futile.

At 7 am, Meade wrote to Grant asking his view “as to the continuance of these attacks, if unsuccessful.” Grant told him that “the moment it becomes certain an assault cannot succeed, suspend the offensive.” Forty minutes after writing to Grant, Meade reminded Hancock of his original orders to attack. Hancock, however, did not attack. Neither did the other corps commanders. Smith called such a move “a wanton waste of life.” The VI Corps partially obeyed the order, according to Wright’s aide, Lt. Col. Martin McMahon, “by renewing the fire from the men as they lay in position.” Griffin Stedman did not even consent to that. “I will not take my regiment in another charge if Jesus Christ himself should order it,” he said with disgust.

At around 11 am, Grant arrived to talk with Meade and then visited the corps commanders. He told Meade in a masterpiece of dry understatement, “The opinion of corps commanders not being sanguine of success in case an assault is ordered, you may direct a suspension of further advance for the present.” The Union attack at Cold Harbor was over.

For the next three days, both sides hunkered down in their entrenchments as sharpshooters made any movement outside of cover a deadly venture. Stubbornly, neither Lee nor Grant asked for a flag of truce to remove the wounded or dead. One Confederate officer summed up the post-battle ordeal: “Thousands of men were cramped up in a narrow trench, unable to go out, or to get up, or to stretch or to stand, without danger to life and limb; unable to lie down, or to sleep, for lack of room and pressure of peril; night alarms, day attacks, hunger, thirst, supreme weariness, squalor, vermin, filth, disgusting odors everywhere.” It was a virtual précis on the Western Front in World War I, still a half century in the future.

Bottled up in their lines, the two sides could only sit and wait, trying as best they could to ignore the screams and moans of the wounded trapped in the sun-baked no-man’s-land between the trenches. “Worse even than the dreadful charge itself,” thought Asa Bartlett of the 12th New Hampshire, “was the sight of comrades lying helpless in their suffering within plain sight, with no means or power to aid or even comfort them.” Bartlett saw one mangled soldier end his suffering by cutting his own throat. Another wounded Federal lay trapped for two days, weakly raising his arm from time to time for help. Pitiless snipers peppered the arm with bullet after bullet.

On June 7, the commanding generals finally agreed to a truce, but by then there were few men left to save. Maggot-riddled corpses were shoveled into shallow graves. In the pocket of one dead bluecoat a diary was found with the chilling last entry: “June 3. Cold Harbor. I was killed.” He was not alone. The battle had cost the Federals more than 6,000 casualties, while the Confederates suffered about 1,500. Union gunner Lewis Bissell spoke for many when he prefaced his letter home, “Cold Harbor and Hell.”

Nine days after the battle, Grant shifted around Lee’s left again, crossing the James River and heading to Petersburg, where the two armies would be locked in siege for the next nine months. Earlier in the campaign Lee had warned Early that they must destroy Grant before he reached the James River, adding, “If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.” He was right. Cold Harbor was Lee’s last major success and, in the words of Lee’s aide, Lt. Col. Charles Venable, “perhaps the easiest victory ever granted to the Confederate arms by the folly of the Federal commanders.” Grant had underestimated Lee and paid dearly for it. He would not make the same mistake again.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments