By Kevin Hymel

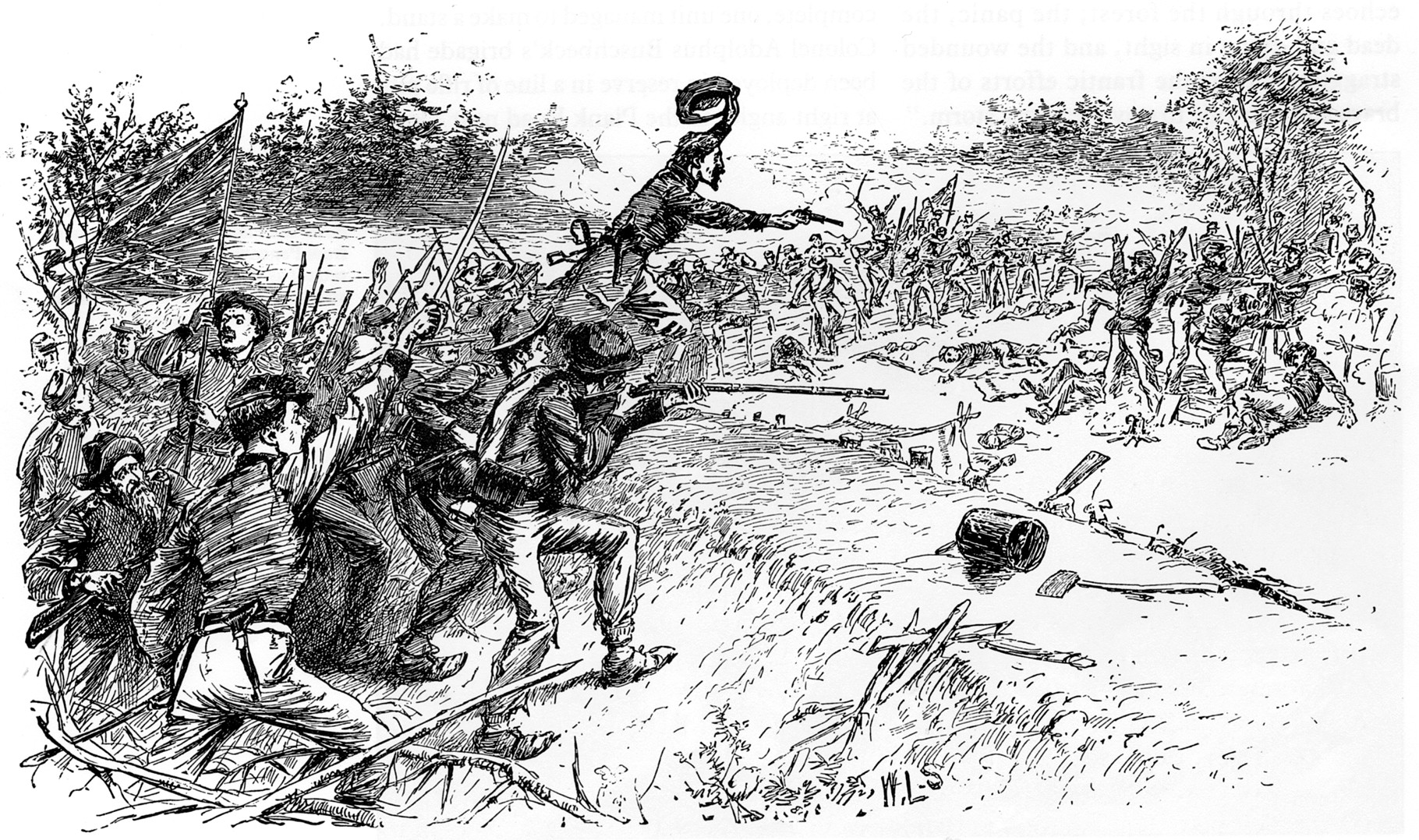

Two brigades of Confederate soldiers crested a slight hill above a wheat field and looked down on the blue clad soldiers waiting for them in the brickyard below. The Union lines fired a swift volley, dropping a number of the Rebels where they stood. The Confederates raised their rifles and fired back.

It was the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, and the Confederates were trying to force the issue before the Union army could gather its strength. The men of the 154th New York Infantry, flanked by the 27th Pennsylvania on their left and the 134th New York on their right, held their ground just north of town between Harrisburg Road and York Pike. Facing eight enemy regiments, the Federals fought desperately, but they were outnumbered three to one.

The 134th was flanked first. Devastating fire poured into it as the unit began to flee the battlefield. The 154th was now exposed. Realizing his unit’s precarious position and not wanting to get captured, the regiment’s commander, Major Daniel B. Allen, ordered a retreat to the left. But not everyone fled—Company C held its ground as Lieutenant Jack Mitchell shouted, “Boys, let’s stay right here!” The few men who were beginning to back away returned to the firing line, a slight fence in front of a brickyard. When Mitchell saw that the rest of the unit was retreating, he changed his mind. “Boys, we must get out of here!” he shouted. Company C broke and ran along with the others.

One of the company’s soldiers, Sergeant Amos Humiston, joined the headlong rush to the rear, where he saw that some of his fellow New Yorkers had already been captured by the Confederates. All around him soldiers were surrendering or being cut down, either by musket fire or saber thrusts from mounted officers. Humiston took off as fast as he could down Stratton Street and across a railroad track. That was the last time anyone saw Amos Humiston alive.

The remnants of the 154th made it to Cemetery Hill, where they spent the next two days under heavy Confederate artillery fire, observing the enemy’s final assault on the Union line on July 3. The 154th went into the Battle of Gettysburg with 265 men. It came out with 58, a unit loss of 78 percent.

A few days after the two armies left Gettysburg, someone found Humiston’s body sprawled in a vacant lot on the corner of York and Stratton streets. He had been shot once in the chest, just above the heart. Realizing that his wound was mortal, Humiston had staggered into the lot between the railroad tracks and the white clapboard home owned by Judge S.R. Russell. Exactly who found him, or when, has never been definitively determined. David Wills, the Gettysburg lawyer who led the efforts to establish a new national cemetery on the outskirts of town (and later invited President Abraham Lincoln to give what became known as the Gettysburg Address), separately named 31-year-old granite cutter Peter Beitler or one of his three sisters-in-law as the person who discovered Humiston’s body. Beitler and his pregnant wife, Emma, were living in the vicinity of Kuhn’s brickyard, where the 154th New York made its forlorn stand. At least one of Emma’s stepsisters—Jane, Anna, or Louisa Schriver—was staying with the Beitlers when the battle began.

At first it was impossible to identify Humiston’s body. Days of rain had drenched the corpse, and there were no identifying letters, numbers, or badges on his uniform, no private papers or primitive dog tags. The only personal item found with the dead soldier was an object clutched tightly in his hand. His eyes were still open, staring at it. The object was an ambrotype, a picture on a piece of glass, of three young children—two boys and a girl. From his death pose, it was obvious that the man had spent the last moments of his life gazing at the photograph. The unknown soldier, still unidentified, was buried in an unmarked grave on Judge Russell’s property.

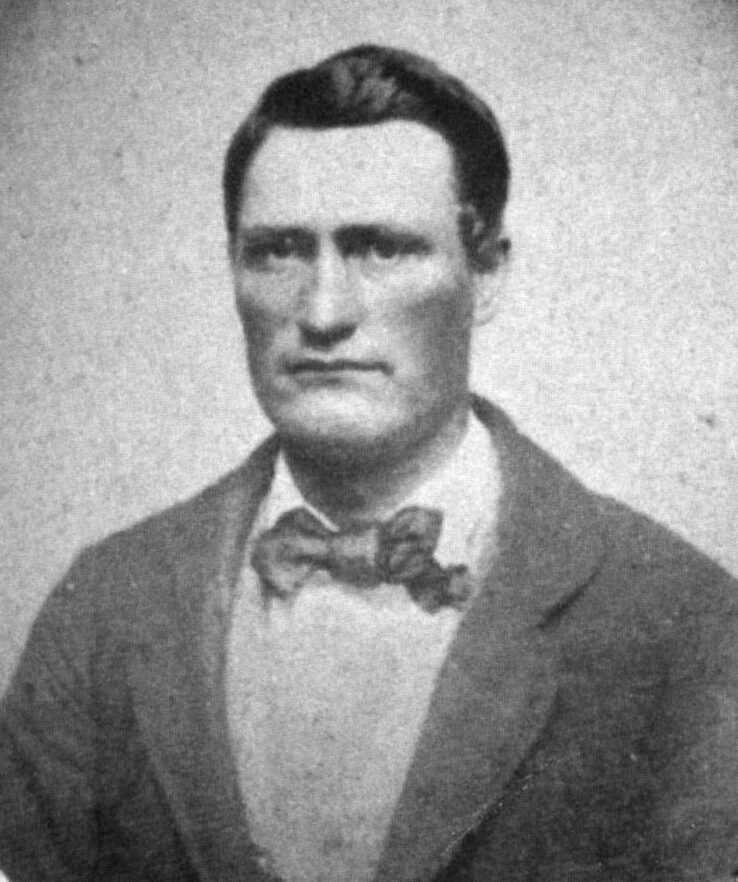

While thousands of men fell in and around Gettysburg during the three-day battle, and many of them were never identified, Amos Humiston would come to symbolize all of them with his final loving gesture. In death, he would have a prominence he never enjoyed in life. By all accounts, Humiston was a typical soldier. Born and raised in Owego, N.Y., on the Susquehanna River near the Pennsylvania border, Humiston was apprenticed to a harness-maker in Tioga County. After five years of study, he abruptly left to become a crewman on the whaling ship Harrison, out of New Bedford, Mass. For the next three years, Humiston braved icy seas, giant mammals, and high winds from Hawaii to the Bering Sea off the northeast coast of Russia. For his troubles, the young man earned a grand total of $200—less than 18 cents a day.

Returning to Tioga County, Humiston settled in Candor, where his older brother Morris had opened a harness and saddle shop. There he met his future wife, a young widow named Philinda Betsy Ensworth Smith, whose first cousin was married to Morris Humiston. Resettling in Portville, N.Y., in Cattaraugus County, Humiston opened his own harness shop with his boyhood neighbor, George Lillie. He and Philinda soon started a family; their three children—Franklin, Alice, and Frederick—were born four years apart.

When the Civil War broke out, Humiston thought it was wrong to stay home. The local pastor, I.G. Ogden, counseled him on the importance of the Union cause and promised to keep an eye on his family while he was gone. Despite his wife’s pleas to stay (she even made him look at their children while they lay sleeping), Humiston joined the 154th New York Regiment.

His unit traveled to Virginia in mid-October 1862 and settled into drab and monotonous camp life. There, the 154th earned the nickname “the Hardtack Regiment” from the men’s practice of trading used coffee beans for hardtack. Promoted to sergeant in January, Humiston participated in Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s ill-fated “Mud March,” an attempt to lure the Confederates into the open by marching up the east bank of the Rappahannock River. Rain and snow turned the roads into a quagmire. Humiston put the best face on the embarrassing misadventure, writing his wife that “we started to attact the rebs but the mud was so deep that we got stuck so we had to give it up and wait till the weather is better.”

Humiston’s next action would be at the Battle of Chancellorsville. The Union Army’s new commander, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, sent the Hardtackers across the Rapidan River, where they flushed out skirmishers and bivouacked for the night, awaiting orders for their next action. Those orders would never come. On May 2, Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson flanked the Union line and smashed into its right. Humiston and the men of the 154th were relaxing around 5 pm when they heard shots fired from the west. The unit immediately formed up just in time to see the first Union stragglers run through the line. More followed, including riderless horses and caissons. As the enemy made their way through the woods, Humiston and his comrades stunned them with devastating fire, but it was not enough. Humiston took a spent bullet to the chest, which fortunately only glanced off his short ribs. “If it had not I should not be writing to you now,” he informed his wife matter-of-factly.

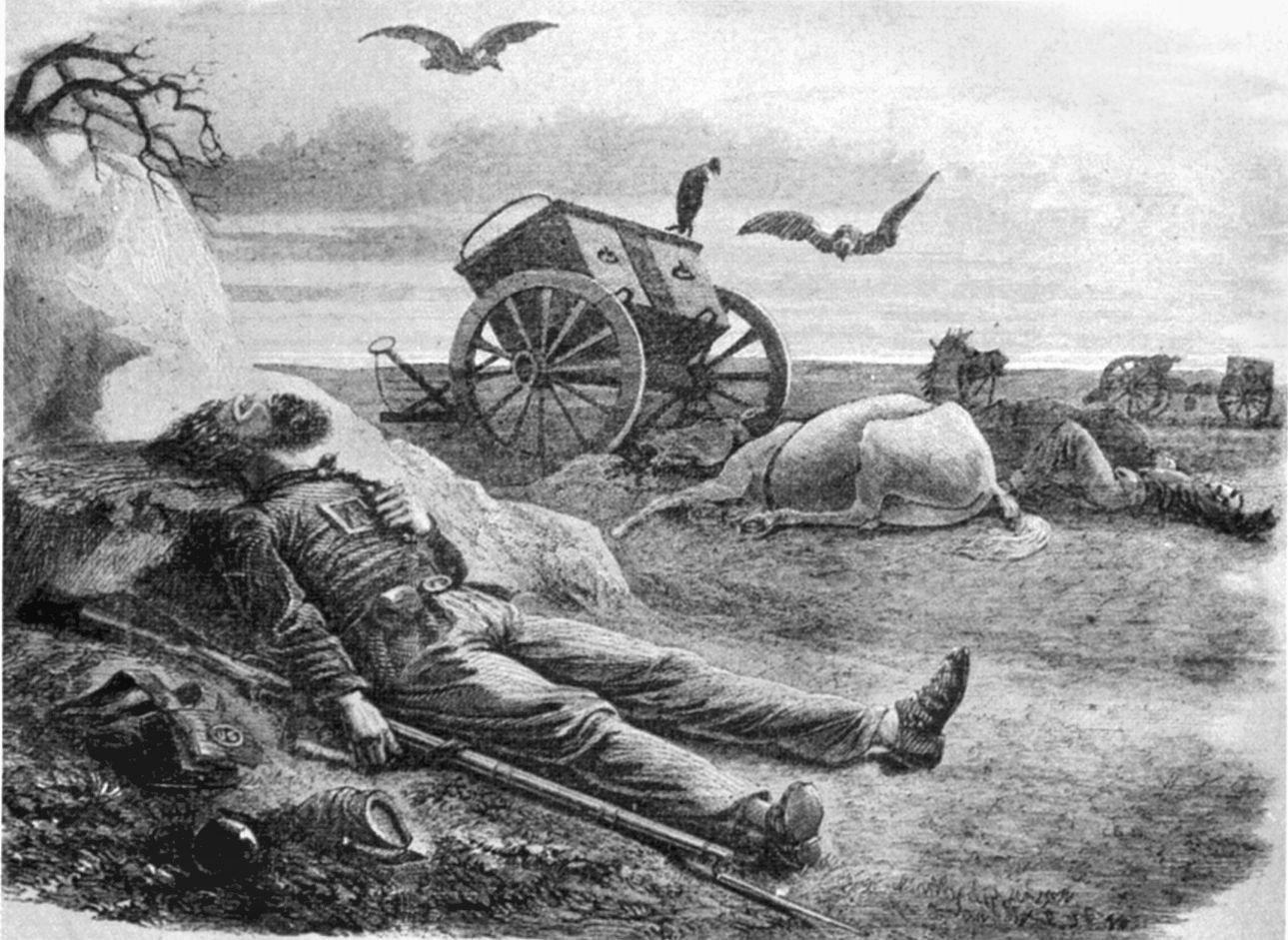

Soon the Confederates overwhelmed the Union troops, who broke and ran. Men in blue fell to the ground under the murderous fire. Twenty bullets tore through the national flag; three struck the flag’s pole. Humiston retreated with the survivors as the sun set. What was left of the regiment would see no more of the battlefield.

Humiston received an unexpected gift when he made it back to camp after the campaign—his wife sent him an ambrotype of his children. “I got the likeness of the children and it pleased me more than eney [sic] that you could have sent me,” he wrote back. “How I want to se [sic] them and their mother is more than I can tell. I hope that we may all live to see each other again if this war dose [sic] not last to [sic] long.” The picture would take on an importance neither he nor his wife could ever imagine.

After Humiston’s anonymous burial, Graeffenburg saloonkeeper Benjamin Schriver somehow came into possession of the ambrotype of the dead soldier’s children. Schriver was a local character, a former sheriff of Adams County who was renowned as a political brawler and all-around scourge of local Democrats. Graeffenburg was 13 miles west of Gettysburg on the Chambersburg Pike, but Schriver presumably had come into town after the battle to check on his daughters, one of whom no doubt gave him the Humiston ambrotype. Schriver took the keepsake home with him and displayed it in his tavern, where it might have faded into obscurity but for a simple twist of fate in the form of a broken wagon axle.

The wagon in question was transporting Philadelphia doctor John Francis Bourns and three colleagues to Gettysburg in the wake of the battle. It broke down in front of Schriver’s inn, and the innkeeper showed the ambrotype to the visitors. Bourns offered to find the family of the fallen soldier if the innkeeper would give him the picture. Schriver agreed.

After helping treat some of the 21,000 Union and Confederate wounded, Bourns returned home to Philadelphia, but not before arranging for the unknown soldier’s grave to be marked more carefully, on the off-chance that he eventually would be identified.

On October 19, 1863, a story was published in the Philadelphia Press, asking, “Whose father was he?” and detailing the final hours of Gettysburg’s unknown soldier. No picture was included with the story—newspapers were unable to print photographic reproductions. Instead, the newspaper provided Bourns’s address in case anyone wanted to contact him. Soon other papers across the North picked up the story, including the American Presbyterian, a religious journal that ran the story along with a description of the picture and the original photo studio’s inscription: “Holmes, Booth & Hydens. Superfine.”

While waiting for a reply, Bourns had the ambrotype made into a carte-de-visite, a hard-backed paper photograph. He sent copies to anyone who contacted him, mostly wives with missing husbands or soldiers with missing comrades. Cartes-de-visite of the children went on sale in Philadelphia, with the profits earmarked for the soldier’s family, if it could be found. If not, the money would go to “some benevolent institution for the benefit of our soldiers.”

In Portville, N.Y., a local townswoman passed the story along to Philinda Humiston, who immediately realized that the description exactly matched the ambrotype she sent Amos. She had the town’s doctor write to Bourns, who received the letter in November. He sent Philinda a carte-de-visite. When it arrived, she found herself looking at a copy of the picture she had sent her husband. She knew then that she was a widow and that her children were fatherless. A month after the article first appeared, the American Presbyterian reported to readers that Philinda had been found and explained somewhat fulsomely that while the widow was saddened by her discovery, “the severity of the blow was tempered by the dying affection of the father, by the tender romance of mystery which enveloped the facts and by the widespread interest the case had awakened in patriotic minds.”

In January 1864, Bourns journeyed to Portville, where he met with town officials and clergymen before being introduced to Philinda and her children and handing her the ambrotype she had sent her husband nine months earlier. Her hands trembled as she received the picture, stained with her husband’s blood. At Bourns’s suggestion, the party dropped to their knees and gave thanks for their good fortune and the divine providence that helped connect a faceless soldier to his family. Privately, Bourns gave Philinda the proceeds from earlier sales of the children’s photograph, stressing that the money was not charity, but rather “an expression of a felt obligation from many warm hearts that sympathized with her in her sorrow.”

The dramatic story of the soldier who died looking at a photo of his children and the subsequent identification of his family spread like wildfire through the North, reaching a pinnacle with the publication in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of a rather fanciful woodcut of Humiston in his death pose. Humiston’s story even made it into a book, Christian Memorials of the War, which came out in 1864. The picture was also used to raise money for the Sanitary Commission. Sales of the picture were brisk and continued long after the war, as Northerners who identified with the story wanted a carte-de-visite for their scrap books. The story was told in innumerable poems and songs, including “The Unknown Soldier” and “The Children of the Battle Field.” The latter work, written by popular balladeer James G. Clark, won a special contest sponsored by the American Presbyterian. Clark’s piece, set to music, sold thousands of copies throughout the North.

After the war, the money collected from sales of cartes-de-visite and the song was used to build a home for orphans of the war at Gettysburg. Spearheaded by the American Presbyterian and Bourns, the money went to purchase a house on Baltimore Pike in Gettysburg that ironically had been Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s headquarters during the battle. (Howard commanded the XI Corps, in which Humiston served with the 154th New York.) Philinda and her three children arrived on October 25, 1866, soon accompanied by other orphans from Pennsylvania, and moved in with much fanfare. Within a year, there were about three dozen orphans living in the house. The Humiston family lived there for three years, with Philinda serving as wardrobe mistress for the home. In October 1869, Philindia married Asa Barnes, a Methodist preacher from Becket, Mass., whom she had met when he visited the orphanage. She and the children relocated to New England, and the home closed down in 1878 amid charges of fraud, misconduct, and mistreatment of children by staff members.

Today, Amos Humiston and his family are remembered in three places in Gettysburg. Amos is buried in the Gettysburg Soldiers’ National Cemetery in grave number 14, section B, in the New York State area. The orphanage, now named Charley Weaver’s American Museum of the Civil War, is located just up the street from the National Park Service’s Gettysburg Visitors Center.

On July 3, 1993, a permanent memorial was dedicated to Amos Humiston on Stratton Street, at the traditional site of his death. The ceremony included a brass band, readings of Humiston-inspired poems, and a rendition of “Children of the Battle Field.” The event was highlighted by the introduction of Humiston’s descendants. The memorial, featuring a likeness of Humiston and his children on a bronze plaque affixed to a five-foot-high granite block, is the only one dedicated to an individual enlisted man at Gettysburg. In that, it is somehow appropriate, since the poignant story of Amos Humiston put a human face to one of the Civil War’s greatest battles.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments