By Lawrence Weber

During the Civil War, the strategic importance of Vicksburg, Mississippi, was readily apparent to both the Union and the Confederacy. Abraham Lincoln considered Vicksburg the key to the war in the West and a necessary target for the Union if they hoped to achieve overall victory. “Vicksburg is the key,” wrote Lincoln. “The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket. I am acquainted with that region and know what I am talking about, and as valuable as New Orleans will be to us, Vicksburg will be more so.”

Vicksburg, situated on a high bluff, was the last Confederate military stronghold on the Mississippi River. The location of the city allowed the Confederacy significant mobility along the strategic river, not only regarding troops, but also supply and communications. Southern President Jefferson Davis understood as well as Lincoln the importance of Vicksburg. In a letter dated May 8, 1863, Davis wrote: “If [Lt. Gen. John] Pemberton is able to repulse the enemy in his land attack and to maintain possession of both Vicksburg and Port Hudson, the enemy’s fleet cannot long remain in the River between those points from their inability to get coal and other necessary supplies.”

A Move to Cut Union Communications

On the morning of May 14, Pemberton was en route to Edward’s Depot just east of Vicksburg, where he was preparing to establish defensive positions, when he received a message from General Joseph Johnston, who had just evacuated Jackson. Johnston informed Pemberton that Union Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman had moved between them with four detached divisions at Clinton. If Pemberton could advance on Sherman from the rear while Johnston advanced from the front, together they could defeat Sherman’s detached divisions. It was a bold idea, but it did not sit well with Pemberton. Advancing on four enemy divisions to the east meant moving the majority of Confederate forces farther away from Vicksburg, leaving the city even more vulnerable to an attack by the Union forces of Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

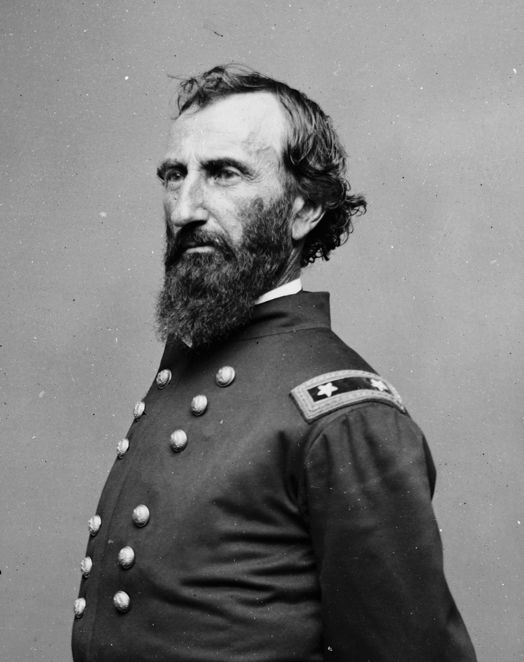

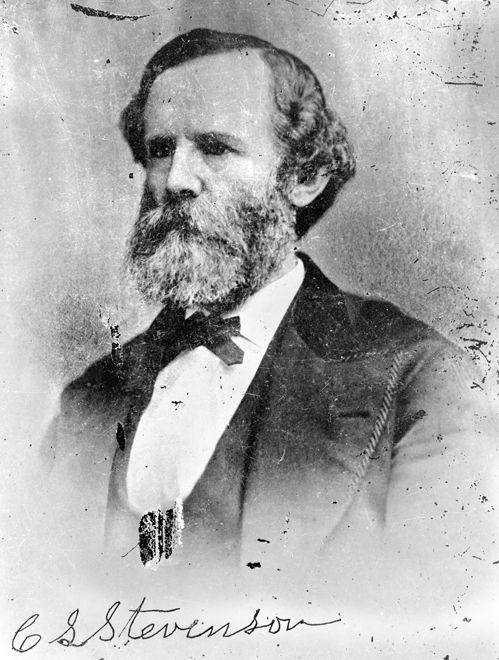

Pemberton convened a council of war with his generals. The opinions in the council were mixed, but a majority of the generals favored the advance that Johnston had proposed. Pemberton, however, felt that moving on Clinton would be suicidal, and instead sided with his two senior divisional commanders, Maj. Gens. William W. Loring and Carter L. Stevenson. They proposed that Pemberton move toward Grant’s rear and cut off his communication and supply lines in the hope of forcing him to retreat. Pemberton agreed and ordered his army to move the next day toward Dillon’s Plantation, located on the main road leading from Raymond to Port Gibson.

Pemberton was unaware that Johnston had evacuated Jackson without a fight. In a letter to his new commander, Pemberton wrote: “I shall move as early tomorrow morning as practicable with a column of 17,000 men to Dillon’s, situated on the main road leading from Raymond to Port Gibson, 7½ miles below Raymond and 9½ miles from Edward’s Depot. The object is to cut the enemy’s communications and to force him to attack me, as I do not consider my force sufficient to justify an attack on the enemy in position or to attempt to cut my way to Jackson.”

At 1 in the afternoon of May 15, Pemberton put his men into motion. Moving his army across Baker’s Creek during the afternoon proved impossible as the creek had swelled tremendously due to a hard-driving rainstorm that had washed away the bridge. Pemberton halted for several hours before eventually moving his army across the creek using the Clinton Road Bridge, 1½ miles to the north. He continued marching toward Raymond Road and eventually gave orders to bivouac for the night near the Elliston plantation, home of Mrs. Sara Elliston, where Pemberton established his headquarters. Upon settling in, Pemberton detailed Colonel Wirt Adams’s 1st Mississippi Cavalry to patrol the vicinity during the night and scout for enemy positions. The night passed uneventfully.

The next morning, around 6:30, Adams encountered the lead Union forces of Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand’s XIII Corps on the Raymond Road and began to skirmish with them. Around the same time that Adams sent word to Pemberton of his encounter, Pemberton received a troubling dispatch from Johnston. “Our being compelled to leave Jackson makes your plan impracticable,” wrote Johnston. “The only mode by which we can unite is by your moving directly to Clinton, informing me, that we may move to that point with about 6,000 troops. I have no means of estimating enemy’s force at Jackson. The principal officers here differ very widely, and I fear he will fortify if time is left him. Let me hear from you immediately.”

Pemberton Takes Champion’s Hill

Pemberton, thinking that Adams was simply skirmishing with a small band of Union forces on the Raymond Road and sensing the urgency in Johnston’s dispatch, ordered his men to begin a retrograde march toward Clinton in the hope of reuniting with Johnston’s forces. As Pemberton and his men began their countermarch, Union forces commenced to attack the head of his column with long-range artillery fire. Pemberton fell back to strategic Champion’s Hill, a 75-foot-high prominence located on the grounds of the Champion plantation.

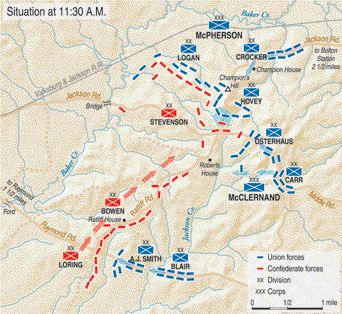

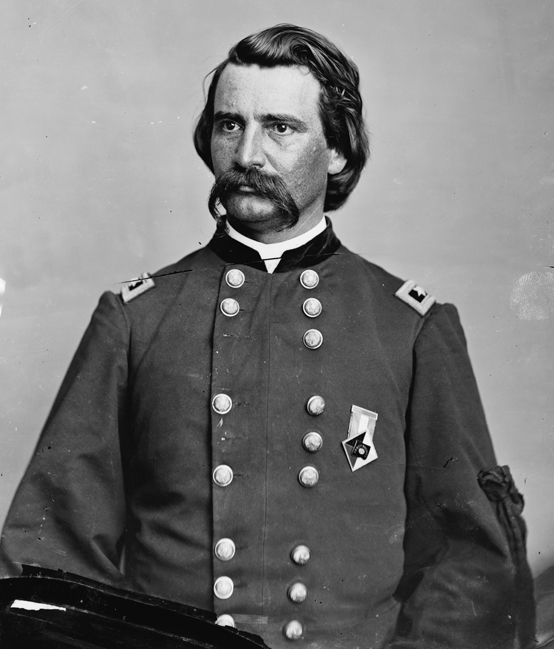

As the early-morning clash grew more intense, Pemberton quickly deployed all three of his divisions into battle lines stretching roughly three miles in length, with Loring on the right, Bowen in the center, and Stevenson on the left. The line of battle was quickly formed, without any interference on the part of the enemy. The position selected was a naturally strong one, and all approaches from the front well covered. Even Grant later commended Pemberton’s position, writing in his memoirs: “Champion’s Hill, where Pemberton had chosen his position to receive us, whether taken by accident or design, was well selected. It is one of the highest points in that section, and commanded all the ground in range.”

The Crossroads: Pemberton’s Weak Spot

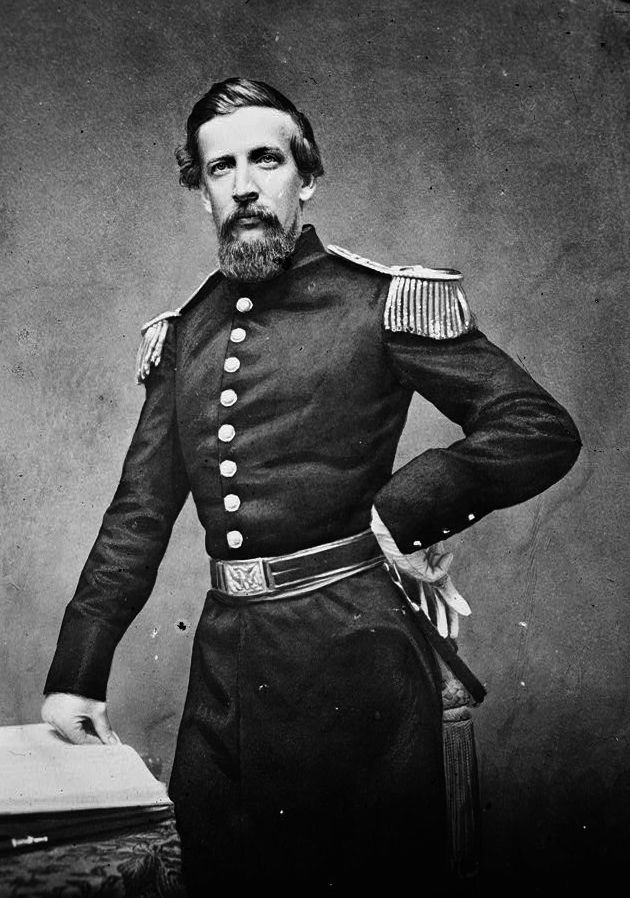

There was one weakness in Pemberton’s battle line, however. The left flank was vulnerable to an attack from the north via the Jackson Road, which crossed at the crest of the hill. This key intersection, known as the Crossroads, became one of the most hotly contested parts of the battlefield. During the early morning of May 16, Pemberton was unaware that a Union force commanded by Maj. Gen. John A. Logan (3rd Division, XVII Corps) was attempting to move from Bolton, down the Jackson Road to the Crossroads, in an attempt to cut the Confederates off from Vicksburg. If the Union forces could surprise Pemberton’s men at the Crossroads and overlap their left flank, Pemberton’s army would be trapped and all would be lost for the Confederates.

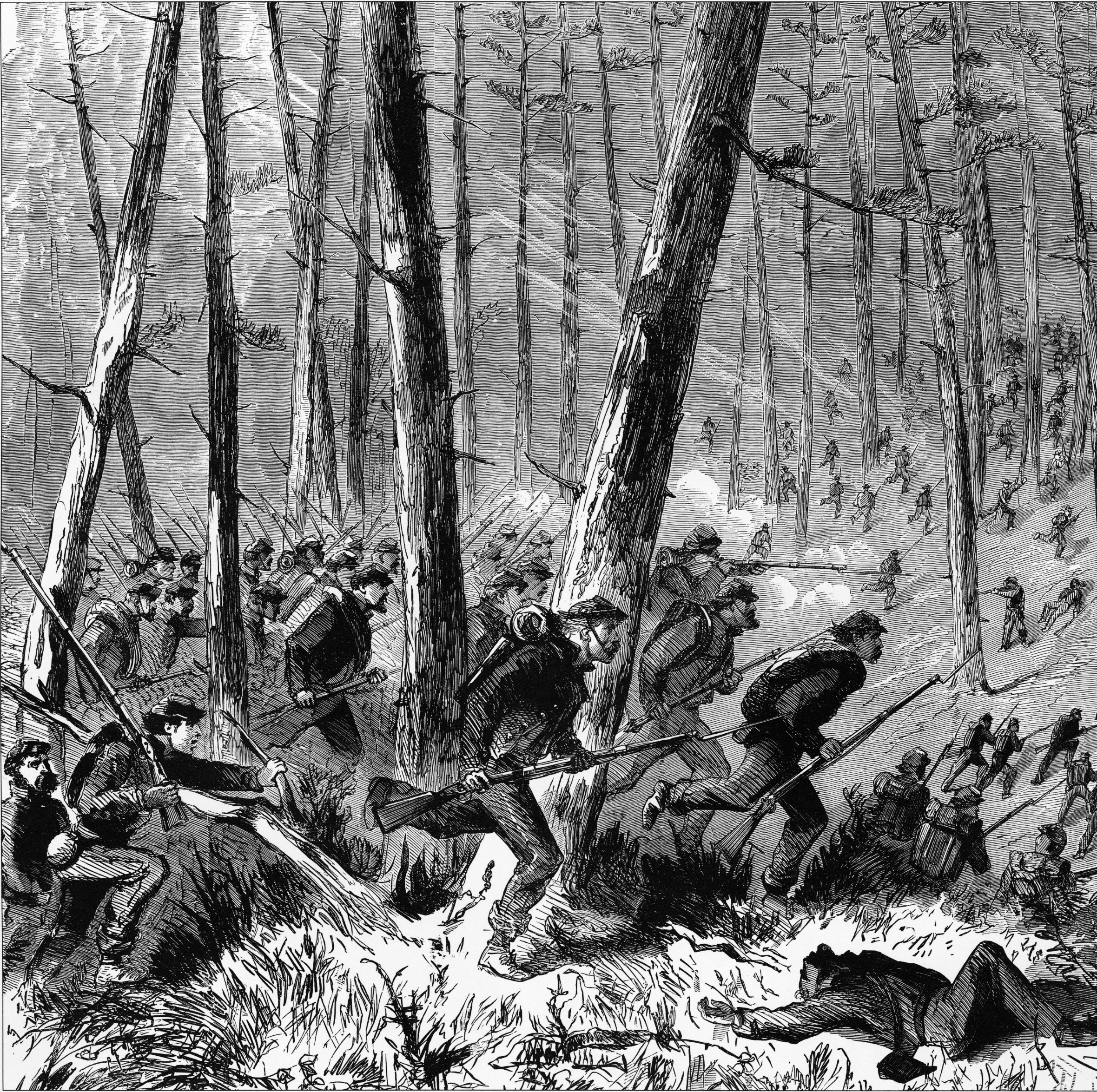

Good scouting on the part of the Confederacy foiled the Union trap before it could be implemented. Around 9 am, a Confederate messenger brought word to Pemberton that Union forces were moving along the Jackson Road toward the Crossroads on their left flank. This information allowed Pemberton to adjust his lines in the defense of the Crossroads, and he ordered Stevenson and his men to establish lines at the crest of Champion’s Hill. If the Confederates were to have any hope for success, the left flank had to hold their positions. One of the most critical and bloody parts of the battle was about to begin.

The Battle for the Crossroads

At about 10 o’clock, the battle began in earnest along Stevenson’s entire front. Stevenson described the fighting in his official report: “At about 10:30 am a division of the enemy, in column of brigades, attacked [Brig. Gen. Stephen D.] Lee and [Brig. Gen. Alfred] Cumming. They were handsomely met and forced back some distance, when they were reinforced, apparently by about three divisions, two of which moved forward to the attack and the third continued its march toward the left, with the view of forcing it. The enemy now made a vigorous attack in three lines upon the whole front. They were bravely met, and for a long time the unequal conflict was maintained with stubborn resolution. But this could not last. Six thousand five hundred men could not hold permanently in check four divisions, numbering, from their own statements, about 25,000 men; and finally, crushed by overwhelming numbers, my right gave way and was pressed back upon the two regiments covering the Clinton and Raymond roads, where they were in part rallied. Encouraged by this success, the enemy redoubled his efforts and pressed with the utmost vigor along my line, forcing it back.”

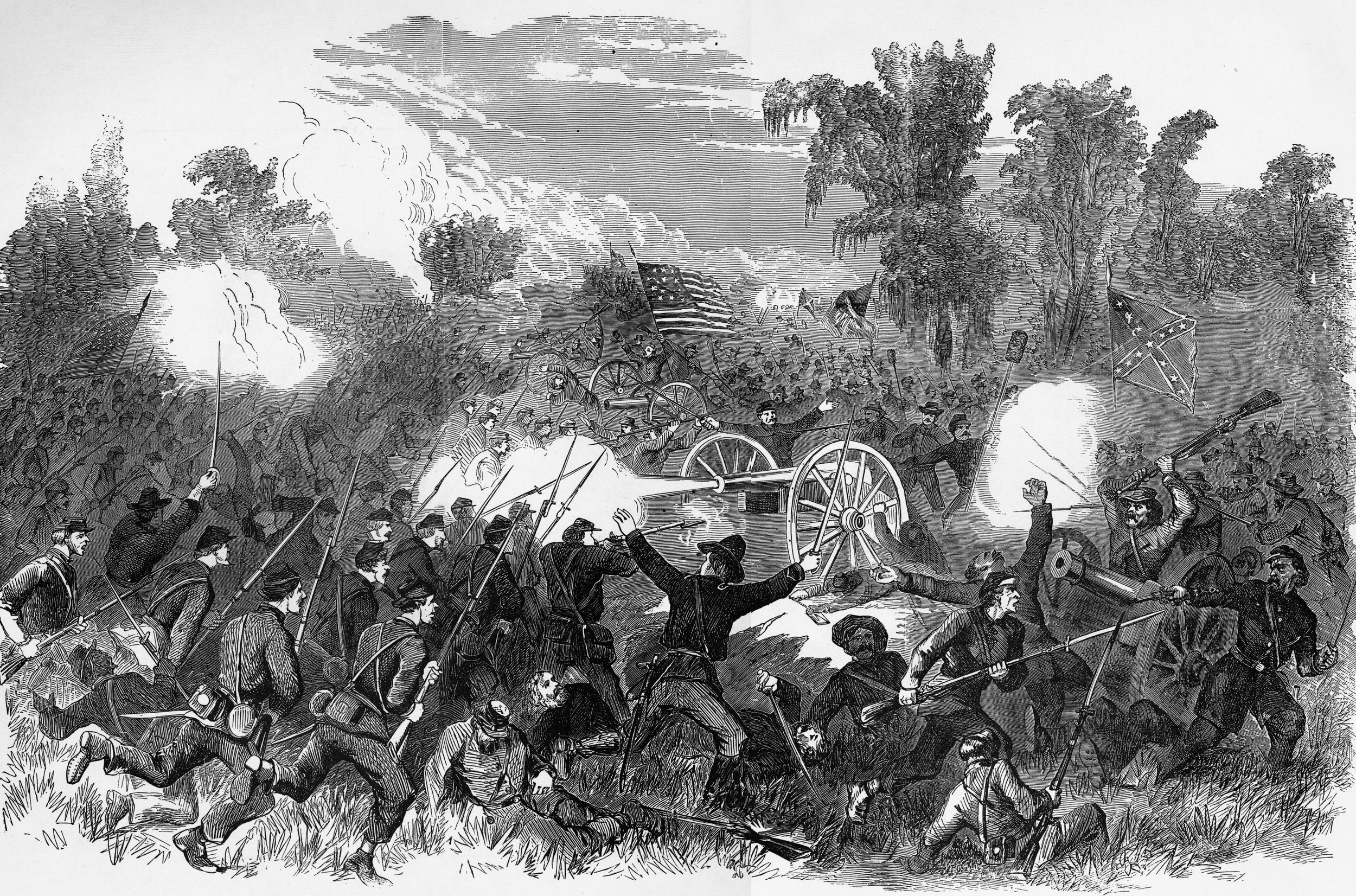

While the Confederate left was surging back and forth against Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s XVII Corps around the Crossroads, other Union forces began focusing their crosshairs on the Confederate center and right. Brig. Gen. Alvin P. Hovey’s 12th Division, XIII Corps, battled along the center of the Confederate position with great success. Hovey ordered Brig. Gen. George F. McGinnis and Colonel James R. Slack to press their skirmishers forward up the hill and follow with their respective brigades. In a few minutes the fire opened briskly along the entire line, continuing for an hour. The Union troops drove forward 600 yards up Champion’s Hill, capturing 11 guns and more than 300 prisoners.

“One Unbroken Deafening Roar of Musketry”

The Confederates would not surrender the ground easily, however, and soon countercharged Hovey’s men in fierce and lethal waves. Leading the countercharge was Brig. Gen. John S. Bowen’s crack 3rd Division, considered by many “undoubtedly the best combat troops in either army.” Bowen’s men received minimal, if any, support from Loring’s division. According to Pemberton’s official report, Bowen’s men, who took the brunt of the assault, performed courageously: “Just at this time a column of the enemy were seen moving in front of our center toward the right. [John C.] Landis’ battery, of Bowen’s division, opened upon and soon broke this column, and compelled it to retire. I then directed Major General Loring to move forward and crush the enemy in his front, and directed General Bowen to cooperate with him in the movement. Immediately on the receipt of my message, General Bowen rode up and announced his readiness to execute his part of the movement as soon as Major General Loring should advance. No movement was made by Major General Loring, he informing me that the enemy was too strongly posted to be attacked, but that he would seize the first opportunity to assault, if one should offer.”

Pemberton grew tired of waiting for Loring to move. Galloping up the plantation road, he found Colonel Francis Marion Cockrell’s 1st Missouri Brigade double-quicking toward him and directed them to support Bowen at Champion’s Hill. Cockrell’s forces crashed into Slack’s Federals with an ear-splitting Rebel yell. Cockrell, a Missouri lawyer who had enlisted in the army as a private and quickly rose through the ranks to brigade command, rode up and down the line, clutching a large magnolia blossom in one hand and a saber in the other. His men reached the hilltop and delivered what one participant termed “one unbroken deafening roar of musketry.”

“An Incessant Show of Shot and Shell”

Eventually, Bowen’s division pushed Hovey’s men back to the crest of Champion’s Hill, where the fight for the center of the line proved extremely hot. Hovey’s division stubbornly fell back, contesting to the death every inch of the field they had won. Colonel George Boomer brought up his 3rd Brigade, which was almost bowled over by McGinnis’s fleeing men. Stragglers shouted that they had left behind 1,200 bodies on the hilltop. Hovey massed 16 cannons from the 1st Missouri, 16th Ohio, and 6th Wisconsin batteries in an open field southeast of the Champion house and ordered them to open fire on the Confederates.

The sound of artillery thundered through Confederate center with lethal force. “Through the rebel ranks these batteries hurled an incessant shower of shot and shell, entirely enfilading the rebel columns,” Hovey reported later. Meanwhile, Colonel Samuel Holmes’s fresh 2nd Brigade arrived on the scene and began pouring shots through the heavy smoke that enveloped the battlefield. As the Confederates fell back again, shouts of joy could be heard from the men in Hovey’s division. By 3 pm, Champion’s Hill, which some of the men had renamed the “hill of death,” was firmly in Union hands. Yet the battle was still not finished.

Counterattack on the Crossroads

By mid-afternoon, the overwhelming numerical strength of the Union forces had broken the Confederate center. In what seemed like perfect timing for the Union, the Confederate left also found itself in disarray. Stevenson’s division had been broken by Union forces around 4 pm and was falling back in unorganized masses. Pemberton did his best to rally the troops one last time on the left flank, but it was of no use. “Observing that large numbers of men were abandoningthe field on Stevenson’s left, deserting their comrades, who in this moment of greatest trial stood manfully at their posts,” reported Pemberton, “I rode up to General Stevenson, and informing him that I had repeatedly ordered two brigades of General Loring’s division to his assistance, and that I was momentarily expecting them, asked him whether he could hold his position; he replied that he could not; that he was fighting from 60,000 to 80,000 men.”

Loring’s division, which was finally on its way to reinforce Stevenson’s men, had taken an ill-planned route and arrived just as Stevenson’s divisions had been broken—too late to make any difference. The order was given to fall back to positions around the Big Black Bridge. As he had done with Cockrell, Pemberton grabbed Brig. Gen. Abraham Buford’s brigade, of Loring’s division, and sent it racing to the front, but not before the enemy had taken possession of the Raymond Road. The 12th Louisiana and 35th Alabama Regiments rushed to Cockrell’s support but were showered by fire from two captured batteries. Pemberton ordered a general retreat.

The Confederates, while retreating, did not know that earlier in the day Union forces had cut off their escape route on the Jackson and Ratliff Roads. In a last-ditch effort to escape from the Union forces, Pemberton ordered a final counterattack against the Crossroads to free up an escape route. Once again, the Crossroads became the center of a lethal storm. Some 4,500 Confederates commanded by Bowen threw themselves into the hazardous final counterattack. Charging with bayonets glistening, the Confederates pushed the Union back almost three-quarters of a mile, briefly regaining control of Champion’s Hill. Sheer numbers were against them, however, and Grant, headquartered in the Champion plantation, ordered his own countercharge, which shattered the Confederates and sent them reeling back in the direction of Vicksburg, via the Raymond Road.

Champion’s Hill: “The Hill of Death”

With the Raymond Road serving as the Confederates’ only avenue of escape, it became imperative to protect it at all cost. Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman’s brigade was selected as the rear guard for the Confederacy. While defending the Raymond Road against heavy artillery fire, Tilghman climbed down from his horse to give directions to one of his men. Just as his instructions were being relayed, an artillery blast thundered in his direction. Tilghman was struck in the chest by a fragment of a Union shell, fired from a position between the Raymond Road and the Coker House, and killed instantly. Rearguard command fell to Loring and his division. Eventually all of the Confederates retreated back to positions near the Big Black River Bridge and areas around Vicksburg. The Battle of Champion’s Hill was over.

While Pemberton and his forces lumbered west toward the Big Black River, the victorious Union forces camped for the night on the bloodied slopes of Champion’s Hill. Sleep did not come easily for the victors; hospital teams prowled the hillside for wounded and dying comrades. General Alvin Hovey, whose division had fought back and forth with the Confederates all day, was almost in shock as he surveyed the remains of the battlefield. “Champion Hill was, after the battle, literally the hill of death,” he wrote. “Men, horses, cannon, and the debris of an army lay scattered in wild confusion. Hundreds of the gallant Twelfth Division were cold in death or writhing in pain, and lay dead, dying, or wounded, intermixed with our fallen foe.”

Grant’s Frustration With McClernand

Grant, too, was reflective. “While a battle is raging one can see his enemy mowed down by the thousand, or the ten thousand, with great composure,” he wrote, “but after the battle these scenes are distressing, and one is naturally disposed to do as much to alleviate the suffering of an enemy as a friend.” For Grant, the victory, while spectacular, was not perfect. Commands given to McClernand to move against the Confederate right flank could have been executed with more speed and order, Grant felt, and he found McClernand to have been deficient in executing his own orders. Had McClernand followed through on orders with reasonable speed, thought Grant, Pemberton’s army could have been trapped and forced to surrender completely.

Grant explained his frustrations with McClernand in his personal memoirs: “McClernand, with two divisions, was within a few miles of the battle-field long before noon and in easy hearing. I sent him repeated orders by staff officers fully competent to explain to him the situation. These traversed the wood separating us, without escort, and directed him to push forward; but he did not come. It is true, in front of McClernand there was a small force of the enemy and posted in a good position behind a ravine obstructing his advance; but if he had moved to the right by the road my staff officers had followed the enemy must either have fallen back or been cut off. Instead of this he sent orders to Hovey, who belonged to his corps, to join on to his right flank. Hovey was bearing the brunt of the battle at the time. To obey the order he would have had to pull out from the front of the enemy and march back as far as McClernand had to advance to get into battle and substantially over the same ground. Of course I did not permit Hovey to obey the order of his intermediate superior. Had McClernand come up with reasonable promptness, or had I known the ground as I did afterwards, I cannot see how Pemberton could have escaped with any organized force.”

This was scathing criticism from the Union commander and strong allegations of serious misconduct against McClernand. In McClernand’s official report, he did not seem to recognize the opportunity that had slipped through his fingers that day. “To say that the Thirteenth Army Corps has done its whole duty manfully and nobly throughout this arduous and eventful campaign is only to say what historical facts abundantly establish,” McClernand wrote blandly.

McClernand had multiple divisions that seemed to have been engaged in a very limited, if any, way during the battle. While Hovey’s division, which was with Grant for the majority of the battle, lost 619 soldiers killed, wounded, or missing, Brig. Gen. Andrew J. Smith’s 10th Division, which was with McClernand, suffered only six wounded soldiers. Brig. Gen. Eugene A. Carr’s 14th Division had only three casualties. Blair’s 2nd Division, XV Corps, which was under the command of McClernand during the battle, reported zero casualties. These were units that could have been used to prevent Pemberton’s forces from retreating. By comparison, McPherson’s 3rd Division lost over 400 men, and the 7th Division lost over 650 men. According to McPherson’s official report: “This, by far the hardest fought battle of all since crossing at Bruinsburg, and the most decided victory for us, was not won without the loss of many brave men, who heroically periled their lives for their country’s honor. Their determined spirit still animates their living comrades, who feel that the blood poured out on Champion’s Hill was not spilt in vain. Every man of Logan’s and [Brig. Gen. Marcellus] Crocker’s divisions was engaged in the battle.”

A Decisive Union Victory

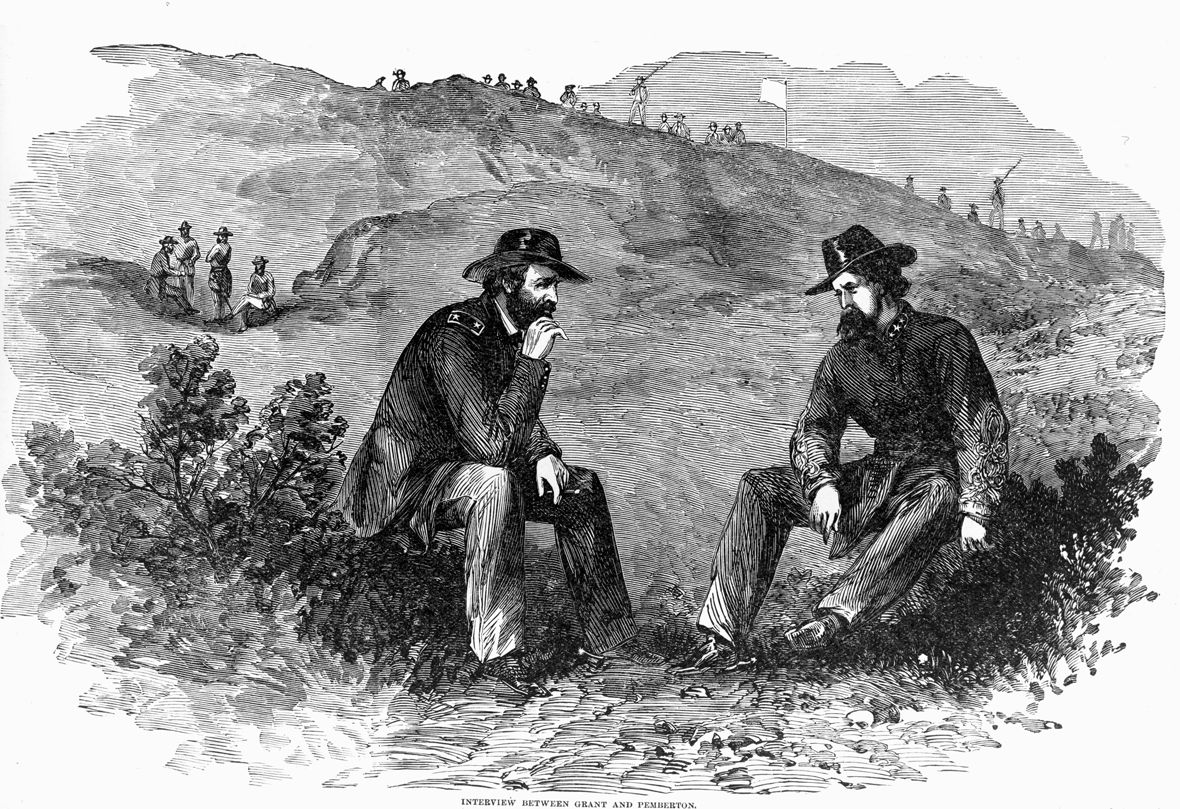

In spite of McClernand’s poor performance, Grant seemed pleased, overall, with the results of the day. He recognized immediately that the Battle of Champion’s Hill had secured the Union’s position between Confederates Johnston and Pemberton. Pemberton was now left with two unpalatable options: either fall back into Vicksburg without Johnston and prepare for a siege, or circle around the Union position at Champion’s Hill and reunite with Johnston to the east, abandoning Vicksburg altogether. Pemberton eventually chose to withdraw into Vicksburg after another Union victory at the Battle of the Big Black River Bridge, which took place the day after Champion’s Hill. Pemberton hoped that Johnston’s army would eventually come to the defense of Vicksburg. It never did. In fact, Johnston ordered Pemberton to

abandon Vicksburg and reunite with his forces, but, under strict orders from Davis to stay in Vicksburg, Pemberton chose to obey the president. He spent the next six weeks besieged inside the city before surrendering to Grant on July 4. The key to the West had been transferred from the pocket of the Confederacy to the pocket of the Union.

Although decisive, the Battle of Champion’s Hill was costly for Grant and the Union. Some 410 soldiers were killed, 1,844 soldiers were wounded, and 187 men went missing. His total engaged forces at Champion’s Hill numbered 32,000 men. Pemberton lost 381 killed, 1,018 wounded, 2,441 missing, and 27 artillery pieces. Included among the dead was General Tilghman. General Bowen, who had fought so hard to retake the hill, would die of dysentery a few weeks later at Vicksburg.

Abraham Lincoln, who recognized early the importance of the key city, wrote to Grant that summer: “My Dear General, I do not remember that you and I ever met personally. I write this now as a grateful acknowledgment for the almost inestimable service you have done for the country. I wish to say a word further. When you first reached the vicinity of Vicksburg, I thought you should do what you finally did—march the troops across the neck, run the batteries with the transports, and thus go below; and I never had any faith, except a general hope that you knew better than I, that the Yazoo Pass expedition and the like could succeed. When you got below and took Port Gibson, Grand Gulf, and vicinity, I thought you should go down the river and join General Banks, and when you turned northward, east of the Big Black, I feared it was a mistake. I now wish to make the personal acknowledgement that you were right and I was wrong.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments