By John Mancini

In the fall of 1755, England and France were again at war for control of North America. The French believed that New France extended from Canada to Louisiana. The British and American Colonists disagreed.

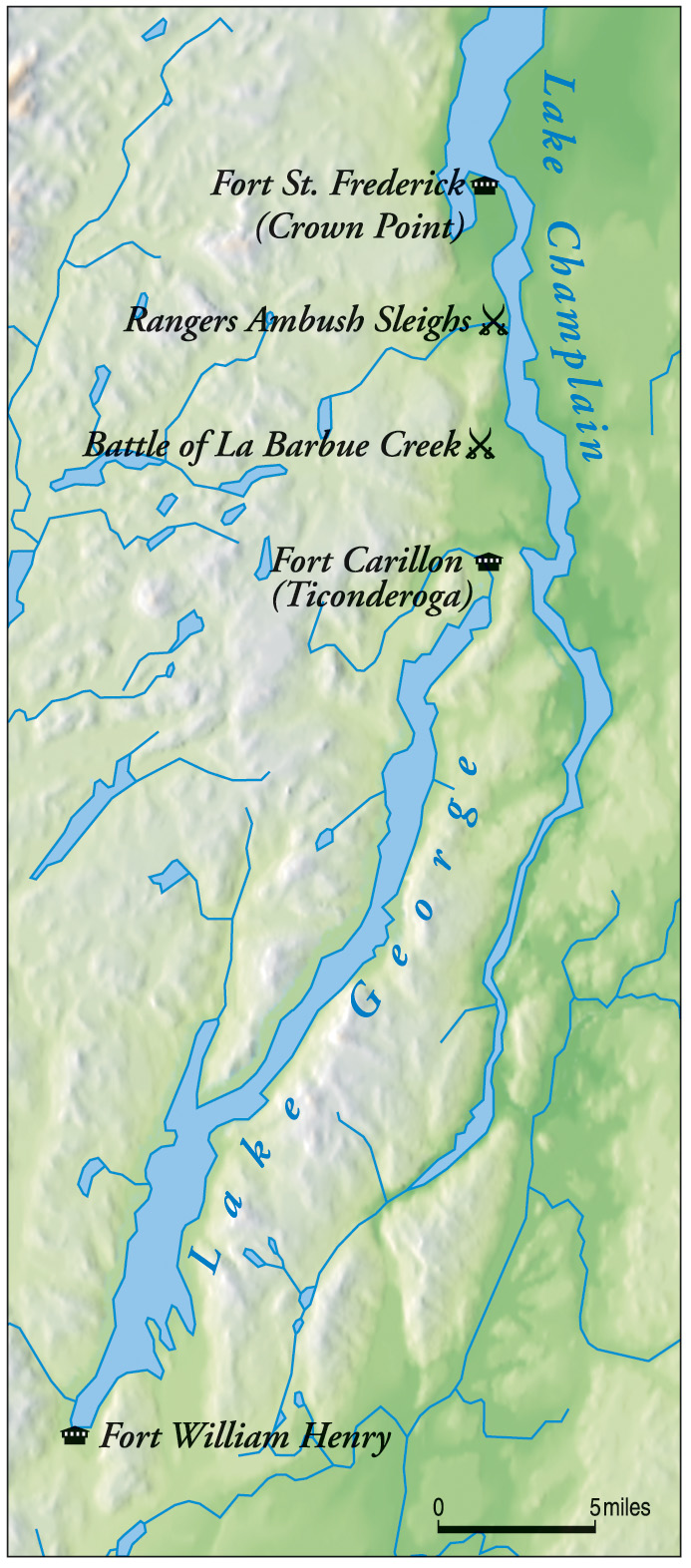

At his headquarters near Lake George, NY, British General William Johnson needed scouts to discover what the French and Indian allies were up to. The enemy was easily able to move unobserved from staging areas at Fort St. Frederick (later called Crown Point by the British) and Fort Carillon (later called Fort Ticonderoga by the British) on Lake Champlain then down Lake George to threaten the New York and New England frontier. If not stopped they could take control of the Hudson River and threaten all of the British colonies along the Atlantic coast.

But General Johnson was unable to get much intelligence as far north as the two French forts. The dark forests were controlled by the coureurs de bois, the French Canadian bushrangers and their Indian comrades. These men had the experience and the instincts for wilderness combat and survival, skills that the British Regular did not have.

The coureurs de bois traveled swiftly and lightly, with hardly more than a musket, tomahawk, scalping knife, and a small pack with dried meat and corn. They moved at will through the northern forests during both summer and winter.

Johnson Needed Bold And Courageous Men Who Could Fight Like the Enemy

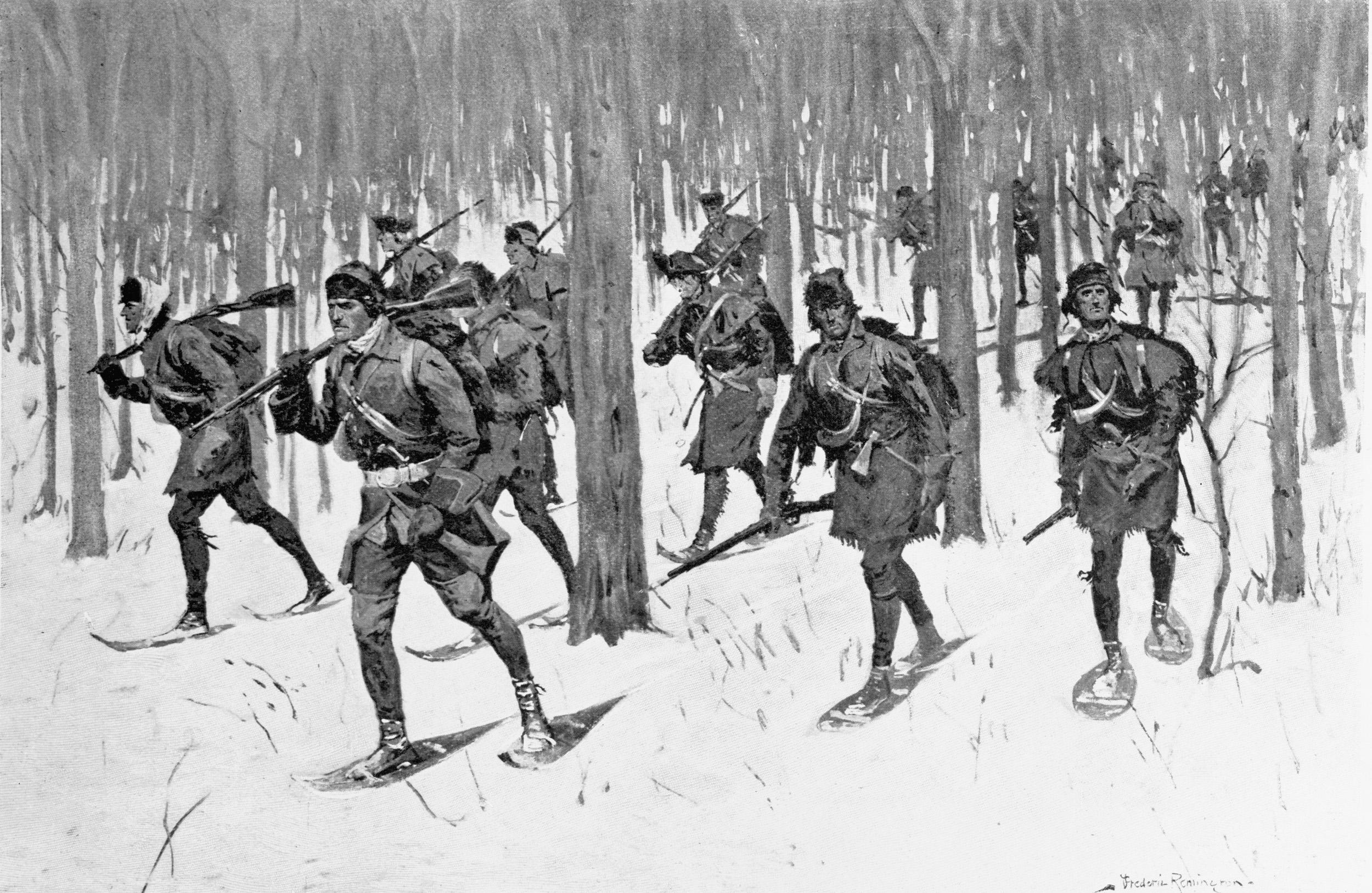

When the freezing northern winter struck, British Regulars stopped military operations, withdrew to the shelter of the stockade, and sat by warm fires. This was the way war was fought in Europe. But the French Canadian captains and their Indian comrades did not stop fighting when the temperatures dropped and the forest was blanketed with knee-high snow. They simply donned snowshoes and continued their patrols.

Johnson needed men who could challenge the coureurs de bois and the Indians. He needed men who could penetrate deep into the ominous wilderness and fight like the enemy. And he needed a leader who could match the courage and boldness of French Canadian commanders such as Marin, Bougainville, and Langlade. For the job he chose a 24-year-old captain in the New Hampshire Militia, Robert Rogers. The young man had grown up on the turbulent New England frontier and had served in Colonial Militia units since he was 14. And he had fought Abenaki and coureurs de bois raiders who ventured out of their major staging area at St. Francis in Quebec.

Rogers mounted his first scouting patrol in late September 1755. He and four militia volunteers waited one night until the sky was inky black, then set off from near Johnson’s encampment at the southern end of Lake George. They sprinted from their hideout of trees to a small whaleboat on the shore. Rogers was taking no chances—Indian scouts friendly to the French kept the enemy commanders well informed of British and American movements.

Throughout the night the men rowed cautiously up the enemy-controlled waterway. At dawn, they rowed into a small inlet on the west side of Lake George where they pulled their boat from the water and hid it in thick brush.

Two militiamen were left to guard the craft while Rogers and the other two men moved inland. For the next three days, the scouts trekked north toward Fort St. Frederick. They struggled through tangled underbrush, crossed ice-cold streams, climbed up and down rocky gorges, always alert for enemy patrols. The September nights had grown cold, but a fire was too risky.

The militiamen finally reached their objective. They watched silently from the concealment of colorful autumn foliage as the French and Indians conducted their daily activities, confident that they were safe from American and British eyes.

Fort St. Frederick was a formidable structure, built in European military style. Gray stone walls were built in a square. Bastions for sentries were located on three corners and a small moat surrounded the walls. Around the fort were lines of white tents and Indian lodges. Rogers estimated an enemy force of approximately five hundred. He wanted to take a prisoner for interrogation, but decided to withdraw before his luck ran out and return to Johnson’s headquarters with the urgent intelligence.

After several days dodging enemy patrols, the scouts arrived where they had left the whaleboat. But they discovered that their fearful comrades had abandoned them. Three days later Rogers and his exhausted companions entered Johnson’s encampment to give their report.

Burning Barns, Killing Cattle

The British commander was impressed and Rogers was ordered to lead frequent scouting patrols throughout the remaining weeks of autumn. Then as the cold northern winter descended, Johnson ordered Rogers to raise a “company of woodsman or rangers” to continue operations against the enemy.

Rogers and his Ranger Company would challenge their adversaries in the dark and shadowy northern forests. They made frequent scouting and ambush patrols deep within enemy-controlled territory and attacked French and Indian patrols around Forts Carillon and St. Frederick. Rogers’ patrols became the only military action against the enemy during the winter months. In January 1756, the Rangers captured an enemy sleigh and took two prisoners on Lake George. In February, Rogers led a long-range reconnaissance patrol to Fort St. Frederick to again estimate enemy strength. Before departing the area with tactical intelligence, the Rangers burned barns and killed cattle.

The Rangers swaggered back to British posts at Fort William Henry and Fort Edward with not only tactical intelligence and prisoners for interrogation, but also with enemy scalps—grisly trophies that raised the morale of the British Regulars, who were accustomed to being victims in the savage wilderness fights. Rogers and his Rangers were viewed with respect by both officers and enlisted soldiers.

Rogers’ successful operations in enemy territory brought more official recognition. In March 1756 he received a commission as Captain of His Majesty’s Independent Company of Rangers. The document stated Rogers’ continued mission: “From time to time, use your best endeavor to distress the French and Indian allies, by sacking, burning and destroying their houses, barns, barracks, canoes, battoes, and by killing their cattle of every kind, and at times to endeavor to way-lay, attack and destroy their convoys of provisions by land and water, and in any part of the country, wheresoever they may be found.”

By November the single Ranger company had grown to four. The organization was officially renamed the Independent Companies of American Rangers, but the whole was commonly called Rogers’ Rangers.

Wobi-Madaondo: The White Devil

Under Rogers’ leadership, the Rangers were effective in accomplishing their missions of scouting, sabotage, and terrorizing the enemy. As respect for Rogers grew among British and colonial soldiers, so did the hatred for him increase among the enemy. The Indians took to calling him Wobi-Madaondo (White Devil), and killing him became a major objective. Rogers had become a real threat to their operations on the northern frontier.

In January 1757 Rogers and his Rangers were given a mission that would not only demonstrate their scouting capabilities, but also test their fighting skills to the limit. On the cold, gray winter afternoon of January 17, Rogers and 84 Rangers filed out of Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George for a long-range reconnaissance patrol to the northern French forts. Each Ranger carried a flintlock musket, powder, and shot for 60 rounds. In addition, each man carried a tomahawk and knife for close combat. They carried in their small knapsacks two weeks’ worth of food rations consisting of dried beef, sugar, rice, and corn meal, as well as an allotment of rum in their wooden canteens. Snowshoes and ice skates were slung over their shoulders. Their blankets were worn over their heads and fastened around the waist with a thick leather belt.

The patrol trudged several hundred yards to the frozen shore of Lake George, put on razor- sharp ice skates, and sped northward. They traveled about 15 miles over the ice before making camp on the east side of the lake at what is called the First Narrows. The following morning Rogers inspected his men. He noted 11 who had sustained severe injuries from the march on the ice, and over their protests ordered them back to Fort William Henry.

Rogers and a force of 74 men continued their march on the ice in the shadows of the mountains along the eastern shore. When the sun shifted they crossed to the western shore. The column advanced 12 miles before making camp on the western side. The morning of January 19 found the Rangers deep inside enemy territory. They continued for another three miles on the ice, but then Rogers prudently ordered them off the frozen lake and they replaced their ice skates with snowshoes for an overland trek. The column marched another eight miles into the mountains before making an evening encampment.

On the 20th the Ranger march continued northeast, three miles from the Lake Champlain shore. As they moved through the bleak, snowy forest, rain began to fall. They made camp early and decided to risk fires to dry out equipment and clothing. The Rangers dug three-foot holes in which to conceal their fires. Over a dusting of gunpowder, leaves, and moss, they struck flint against steel. Soon wafts of smoke were gently nursed with small twigs until the pits contained warm, dancing flames.

The next morning, Rogers led his Rangers east to the frozen shore of Lake Champlain. The men broke out of the forest midway between Forts Carillon and St. Frederick and rapidly established ambush positions along the bank. Scouts almost immediately reported two French sleighs traveling toward them over the frozen lake from the south. Rogers swiftly prepared to capture the enemy patrol.

Three French Prisoners Escaped Riding Horses Over the Frozen Lake

Lieutenant John Stark and 20 Rangers dashed north to block the enemy. Rogers and 30 men moved south along the shoreline to halt their retreat. Captain Thomas Speakman remained in the center with his force to execute the ambush and capture. As the sleighs approached Speakman’s sector, Rogers observed with alarm what was appearing down the lake. Eight more sleighs were emerging from the foggy mist and rain. He ordered two runners to warn Speakman and Stark to hold their positions until the entire French column had passed into the Ranger ambush zone. The breathless messengers gasped out the news to Speakman, but were unable to reach Stark in time.

Stark and his men followed the original plan and sprang the trap. Rogers and Speakman then joined the assault. Seven Frenchmen quickly became prisoners, but three managed to escape by leaping onto horses, slashing the horses’ traces, and galloping back down the frozen lake. The Rangers raced on foot in pursuit, but were quickly outdistanced by the fleeing enemy. In addition, the rear sleighs could not be reached as they wheeled about and sped back to Fort Carillon.

Rogers quickly separated the prisoners and interrogated them. The Frenchmen gave him chilling information. Two hundred Canadians and 45 Abenaki and Algonkins had arrived at Fort Carillon and 50 members of the Nipissing tribe were expected to arrive that night. In addition, the garrison had 350 French Regulars. The prisoners also reported that there were another six hundred enemy at Fort St. Frederick.

Rogers faced the grim realization that the French commander at Fort Carillon would soon be told of the Ranger presence in his vicinity—and that the enemy would move swiftly to intercept his withdrawal to Fort William Henry. Rogers considered his options. His survival instinct, and the Ranger tactic he had established, called for a return from enemy territory by a different route. But this would entail crossing the frozen lake and returning to Fort William Henry on the eastern side. Unfortunately, this choice would expose the Rangers to possible observation by enemy scouts. Another course of action would be to avoid exposure on the open lake and return by a different route on the western side. But this would require the exhausting, time-consuming task of breaking new trail through deep, wet snow. Rogers made the difficult decision to withdraw over the same route the Rangers had used to infiltrate the enemy-held area. This course of action was riskier, but he thought it provided the swiftest return to the safety of friendly lines. Accordingly, Rogers waved the Rangers back into the gloomy mist of the snow-covered forest. The men loped on snowshoes back to their last campsite, where they stopped to again build concealed fires and dry out their flintlocks.

Meanwhile, Captain Paul Louis Lusignon, commandant of Fort Carillon, was notified by late morning of the Ranger ambush of his supply sleighs to Fort St. Frederick. He immediately ordered Ensign Charles-Michel Mouct de Langlade and his Canadians and Indians to intercept Rogers’ force.

Langlade was no stranger to Northwoods fighting. Of French and Indian heritage, he was a skilled woodsman and guerrilla leader; in fact, he had been one of the leaders in the ambush and massacre of Braddock’s force near Fort Duquesne on July 9, 1755. Lusignon also ordered out his French Regulars, who followed a short time later. They were commanded by Captains De Basserode and Granville along with Lieutenant D’Astrat.

Eager to Fight Rogers’ Rangers

The Rangers broke camp at about 1:30 in the afternoon and moved south toward Fort William Henry. They marched in single file with Rogers in front accompanied by Lieutenant Kennedy. Captain Thomas Speakman was in the center of the line and Lieutenant John Stark followed with the rear guard. Sergeant Walker was also in the rear of the column with the prisoners. The Rangers dashed south, hoping to evade observation by the enemy at Fort Carillon.

But the French commander had guessed Rogers’ escape plan. A force of over one hundred Canadians, Indians, and French Regulars was moving to find and destroy the hated enemy. The French were eager for a fight with Rogers and his Rangers. Langlade and his scouts found the Rangers at about 2 o’clock in the afternoon several miles northwest of Fort Carillon. The enemy commanders quickly established a lethal half-moon ambush formation among the trees of a 75-foot-wide ravine.

As Rogers approached the location he realized that the terrain was ideal for an enemy trap, but decided that the valley offered more concealment than movement along the ridge lines. With Rogers leading, the column moved single file through the snow-covered valley, crossed a stream, and began its ascent. As Rogers and his advance element crested the ridge, they were met by a deadly volley of gunfire. Some volleys were fired from as close as five yards. War cries and fierce shrieks erupted and echoed through the cold winter air. Rogers was slammed to the ground by a musket ball that grazed his forehead. Kennedy was killed instantly by the swarm of hot lead. Other Rangers fell to the snowy ground clutching agonizing wounds.

The French and Indians surged forward to exploit the surprise attack. Rogers fought off the momentary shock from his wound and yelled for the Rangers to withdraw back to the opposite hill. The aggressive enemy tried to cut off the retreat. But then Stark’s rear guard joined the fight. Stark and about 40 Rangers formed a battle line on the hill and covered the withdrawal with intense fire support. Nevertheless, the two forces had become intermingled in the valley, and there was close, savage fighting, hand to hand and tree to tree.

A Daring Counter-Attack by the Rangers Contained the Enemy Flank

Rogers dashed to the Ranger skirmish line on the ridge. As more men reached the hill, the Rangers were able to return gunfire and halt the momentum of the enemy attack. Rogers now directed the defense, and at about this time shouted the grim order to kill the prisoners, fearing that they would yell out information to their comrades. This was done.

The battle continued throughout the dreary winter afternoon. The enemy attempted to flank the Ranger line, but were stopped by a daring counterattack. Rogers was wounded again as another enemy ball found its mark. This time the injury was to his wrist, which prevented him from loading and firing his musket. But he continued to dart back and forth along the skirmish line, keeping morale high as the French and Indians pressed the Rangers with both frontal and flanking assaults. As darkness descended, the firing stopped and an ominous silence returned to the forest. Rogers faced the chilling reality that he and his Rangers were pinned down by a numerically superior enemy force and without hope of reinforcements. This fact was also apparent to the French commanders. The stillness was broken as a voice from the enemy lines echoed through the cold, snow-covered forest.

“Rogers! Captain Rogers! You and your Rangers give yourselves up. We promise quarter if you do it now. You will be treated with kindness and mercy. It would be a pity for so many brave men to be lost.” After a pause, the enemy spokesman continued: “We have great esteem for your ability. But even you must see that all is lost. We warn you, give up! Reinforcements are on the way now. They will be here soon, and if you don’t give up now, we’ll cut you to pieces in the morning.”

“Go to Hell!” Rogers shouted, as a roar of cheers echoed down the Ranger battle line.

As the pale winter sunlight faded, Rogers called his officers together. They all recognized their grim situation. The unanimous decision was to withdraw. In Rogers’ words: “We had great numbers of wounded that could not travel without assistance, our ammunition being nearly expended, considering that we were near to Ticonderoga [Fort Carillon], from whence the enemy might easily descend and overpower us by numbers, I thought it expedient to take the advantage of the night to retreat and gave orders accordingly. The next morning we arrived at Lake George, about six miles south of the French advanced guard. I dispatched Lieutenant John Stark with two men to Fort William Henry to procure conveyances for our wounded.”

As Stark and his men raced south for help, Rogers and the remaining Rangers continued the march on the ice to further distance themselves from the French. Through the dim winter light, they saw a dark shape moving on the horizon to their rear. Several Rangers ran toward the staggering figure and discovered that it was Sergeant Joshua Martin, who had been severely wounded and left for dead. The Ranger sergeant had regained consciousness after the withdrawal and had painfully followed their tracks.

Meanwhile, Stark and his exhausted men pushed the limits of endurance to get help for their struggling comrades. They covered the 40 miles to Fort William Henry by nightfall. A Ranger rescue party with sleighs raced up the frozen lake and was able to link up with Rogers the following morning. Rogers reported that “our whole party—which now consisted of forty-eight effective, and six wounded men, arrived at Fort William Henry the same evening, the 23rd of January 1757.” Rogers and his Rangers had executed a successful night withdrawal with their wounded. But, tragically, the dark night that had provided cover to evade the French also caused them to leave behind three injured men besides Joshua Martin.

“Seeing This Dreadful Tragedy, I Concluded, if Possible, to Crawl into the Woods and There Die of My Wounds”

Private Thomas Brown and Captain Thomas Speakman had received severe gunshot wounds during the initial volley. The two men struggled to a position of relative safety behind the Ranger skirmish line. They were joined by a British Regular named Robert Baker who had volunteered for the patrol to learn Ranger tactics. As the Rangers silently withdrew from their firing positions, the three were presumed dead and thus overlooked. The wounded men began to sense the eerie quiet in the forest as daylight appeared. Muffled calls to their comrades went unanswered. They realized they were alone.

Agonizing pain and numbing cold forced them to risk building a fire. Their worst fear quickly materialized. Brown spotted a warrior creeping toward the camp and managed to crawl into the brush and avoid detection. But the Indian saw the other two men. He scalped Speakman and carried off Baker.

Brown later wrote: “ Seeing this dreadful tragedy, I concluded, if possible, to crawl into the woods and there die of my wounds, but not being far from Captain Speakman, he saw me and begged me for God’s sake to give him a tomahawk that he might put an end to his life! I refused him, and exhorted him as well as I could to pray for mercy, as he could not live many more minutes in that deplorable condition, being on the frozen ground covered with snow.”

Without shoes, Brown made an effort to escape the enemy force. He crawled through the snow-covered forest, evading French and Indian patrols for the remainder of the day and the following night. But the next morning his luck ran out—he was spotted by four Indians. Brown tried to outrun them, but in his weakened condition he could not outpace them and they gained quickly. Still, he ignored their shouts for him to halt. They were about 15 yards behind with cocked rifles, and Brown hoped they would fire and kill him. Instead the warriors dashed forward and took him captive.

They treated his wounds with dry leaves and marched him a short distance to a larger group of French and Indians. He was brutally interrogated by a French interpreter regarding the size and present location of the Ranger force. But he held up and gave evasive answers despite being shown the mutilated bodies of Kennedy and Speakman. Brown begged for a pair of shoes and food, but the French interpreter told him that his request would have to wait until he had walked the one-and-a quarter miles to Fort Carillon. Nevertheless, the Indians who had captured him gave him shoes and bread before the trek. He was also reunited with Robert Baker, who had been taken prisoner earlier.

18 Killed, 27 Wounded, Seven Captured

The order was given to begin the march to Fort Carillon. Baker was very weak and was unable to walk. A warrior grabbed his hair and raised his tomahawk; Brown quickly intervened and pulled Baker’s arms over his shoulders and got him on his feet. Despite his own exhaustion, he was able to get his comrade to the fort.

There Brown was threatened with death in retaliation for the Ranger executions of the French prisoners, but he was eventually brought to Montreal and remained a prisoner of the French until November 1758.

Thus ended this Battle of LaBarbue Creek. Both sides claimed victory. Seventy-four Rangers were engaged, 14 were killed, nine wounded, and seven captured. An estimated 145 to 250 French, Indians, and Canadians were engaged. They reportedly lost 18 killed, 27 wounded, and seven captured.

Rogers was sent to Albany for medical treatment of the wounds he received in this, the first major engagement fought by his Rangers. It was also the first time Rogers had not brought back all of his men from a mission. But British officers were supportive and the consensus was that Rogers and his Rangers had “behaved gallantly.”

Official recognition came swiftly from General Abercromby through his nephew Captain James Abercromby. “I am heartily sorry for Speakman and Kennedy … as likewise for the other men you have lost. But it is impossible to play at bowls without rubs. I regret not having been in the action which Major Eyre (commander of Fort William Henry) so correctly describes as gallant behavior. I am certain it is better to die with the reputation of a brave man, fighting for his country and good cause, than either shamefully running away to preserve life or lingering out an old age and dying in one’s bed without having done his country or king any service. You cannot imagine how all of the ranks here are pleased with your conduct and men’s behavior. For my part, it is no more than I expected. I was so pleased with appearance when I have gone out with them, that I took for granted they would behave well whenever they met the enemy.” Rogers gave a simple but poignant description of his Rangers’ performance. “Both officers and soldiers that I had the honor to command behaved with undaunted bravery.”

Rumors of the virtual destruction of Rogers’ Rangers circulated among the French and Indian allies. But the commander at Fort Carillon did not share in the elation. He feared that the Ranger presence in his area was a prelude to an attack on his installation. He therefore launched a series of assaults on Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George.

The Legacy of Rogers’ Rangers

The final campaign against this British wilderness outpost ended in August 1757. After a week’s siege by General Marquis de Montcalm and an army of 11,000 French Regulars, Canadians, and Indians, surrender was forced. Colonel John Munro accepted Montcalm’s generous terms after he was confronted with a message to him, but which had been intercepted by the French. The dispatch was from General Webb at Fort Edward, 14 miles away, saying, Webb was unable to send reinforcements. The Indian allies were enraged at the peaceful resolution of the siege and swooped down on the English and colonials as they marched away from the fort in obedience of the surrender terms. This siege and ensuing massacre are depicted in James Fenimore Cooper’s novel, The Last of the Mohicans.

John Stark would use his battle experiences with Rogers’ Rangers as an American officer during the Revolutionary War. He commanded the New Hampshire Regiment at Bunker Hill and went on to lead patriot forces at the battles of Princeton, Trenton, and Bennington. He retired from the Continental Army with the rank of major general.

Rogers and his Rangers would fight another violent wilderness battle on snowshoes in March 1758, in the general vicinity of the LaBarbue Creek engagement. But the most memorable action of Rogers’ Rangers was the 1759 St. Francis Raid—the destruction of this French and Abenaki Indian staging area near Montreal brought him the adoration of New England.

From this high point, Rogers’ life and reputation began a slow decline. At the end of the French and Indian War he was deeply in debt. He had equipped and paid his Rangers from personal finances and loans. And because of his poor recordkeeping, or preoccupation with fighting the enemy, he was never able to get proper reimbursement from the British. He would spend many years in England trying unsuccessfully to resolve the issue. Rogers returned to America on the eve the of the Revolution, but the years in Britain had kept him detached from the politics of America and the movement for independence.

Consequently, he was torn between his sense of duty as a British officer and the American patriot cause. Eventually, Rogers offered his services to the Continental Army, but was rejected by General George Washington who viewed him with disdain and suspicion. Rogers then joined the British Army, but was relieved of his command after battle failure. He returned to England in 1780 and died in poverty 15 years later.

Despite Rogers’ repeated failures and tragedies following the French and Indian War, his military legacy lives on in the U.S. Army and Special Operation Units.

This man and his men became of great interest when I was a boy. Everyone of our SOG units stem from them.