By Michael E. Haskew

For three centuries, feudal Japan remained comfortably isolated from the rest of the world. By order of the Tokugawa Shogunate, foreigners landing on Japanese shores risked immediate execution. Christian missionaries from Europe were systematically put to death or expelled. All that changed in the summer of 1853, when a flotilla of imposing black warships of the United States Navy, led by Commodore Matthew C. Perry, dropped anchor in Tokyo Bay and demanded that Japan open its doors to the West. Overawed by the show of power, the Japanese hastily agreed, but the ruthless European colonization of its vast neighbor, China, caused Japan to take steps to protect itself from similar exploitation. With characteristic thoroughness, the Japanese embarked on a crash course of modernization and economic growth that soon transformed the island nation into a regional and potentially global superpower.

By the end of the 19th century, modern Japan was ready to emerge onto the world stage. Hand in hand with a more pragmatic world view and burgeoning industrialization came a modern Japanese military. Civil war had erupted in the 1870s, ending with the defeat of the old-line samurai and the emergence of the Meiji monarchy. In the wake of that war, Japan’s leaders pursued industrial and economic expansion with renewed fervor, and during the decade from 1895 to 1905 the government’s military-related spending approached 40 percent of its budget. The scope of Japanese political interests expanded apace with the country’s economy, and establishing an appropriate sphere of influence in the Far East assumed paramount importance in Japanese planning. National security concerns brought about a frank assessment of Japan’s strategic strengths and weaknesses, particularly the need to insure continued access to vital raw materials.

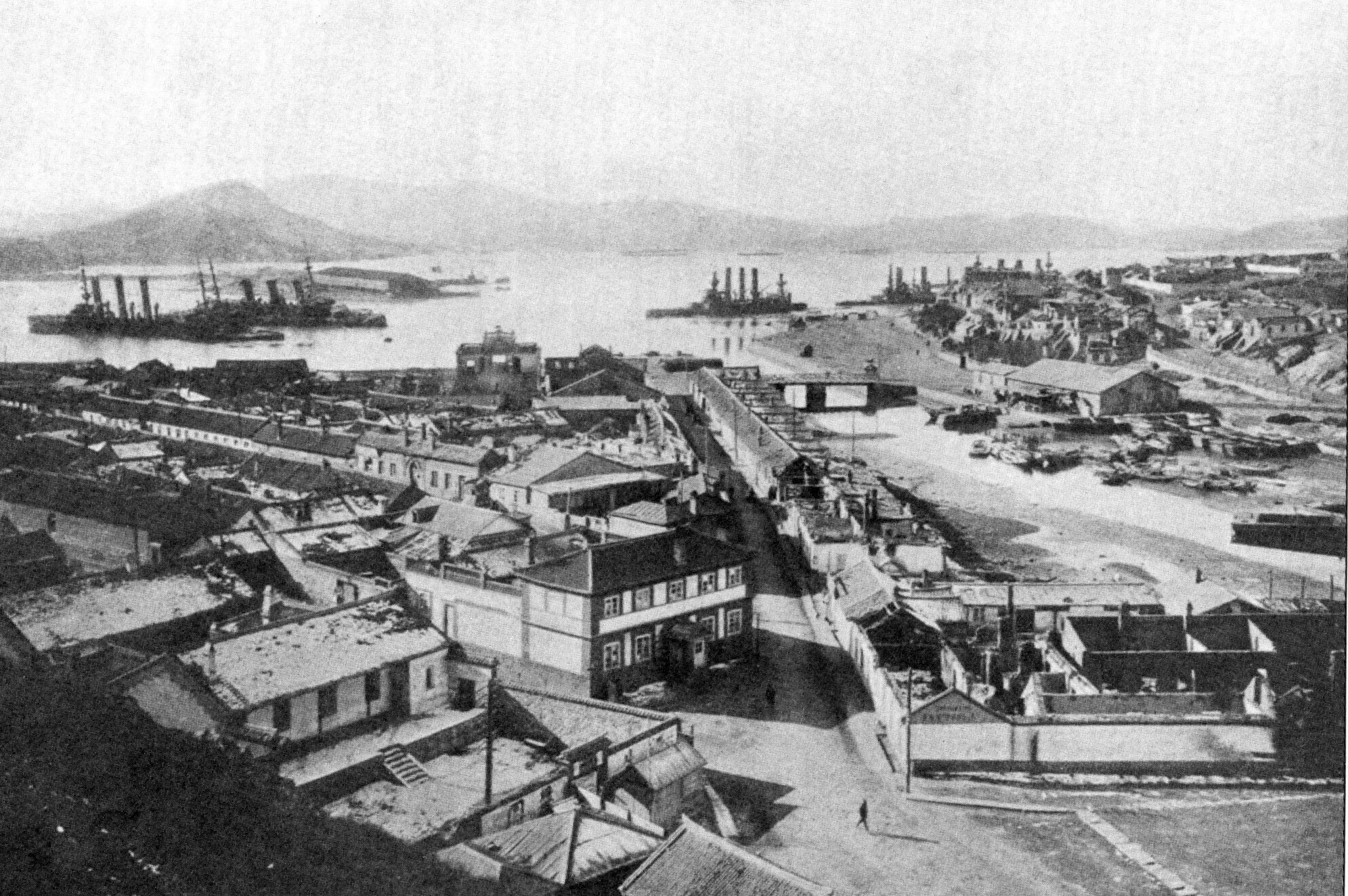

Inevitably, Japanese interests conflicted with those of other countries, both Asian and European. One nation, in particular, posed a worrisome challenge for Japan. For decades, Czarist Russia had pursued a similar campaign of expansion on the Asian continent, and the increased assertion of Japanese influence placed the two countries on a collision course. The Treaty of Shimonoseki, which had followed Japan’s swift and convincing victory over China in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, gained the Japanese a controlling influence in Korea, then a Chinese satellite, as well as the Liaotung Peninsula in southern Manchuria and the strategically vital harbor of Port Arthur at the peninsula’s tip. Russia, with the support of France and Germany, forced Japan to return its recent territorial gains, and subsequently coerced the Chinese into granting them a lengthy lease to Port Arthur. During the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, Russian troops were deployed in China, and after the revolt was put down these troops proceeded to occupy most of Manchuria.

Although the Russian incursion into Manchuria was troubling to the Japanese, it was Russia’s undisguised ambitions to control Korea that Japan found intolerable. Korea, one Japanese diplomat remarked, “was a dagger pointed at the heart of Japan.” The government moved swiftly to shield itself from such a threat. In 1902, Japan entered into an agreement with Great Britain which guaranteed that if Japan found itself at war, the British would come to their aid if a second country entered the conflict. By the turn of the century, the balance of power in the Far East consisted of Imperial Russia, supported by France and, to a lesser extent, Germany, and Japan, which was supported by Great Britain. The United States also favored Japan in order to counter any expansion that might negatively impact foreign trade or endanger its possessions in the Pacific, particularly the Philippines and the island of Guam in the Marianas. Diplomatic jockeying and military posturing continued unabated during the first years of the new century.

In August 1903, Japan and Russia sat down at the bargaining table in a last-ditch attempt to resolve their Korean differences diplomatically. The Russians refused to entertain the notion that Japan might actually go to war over Korea. Moreover, many Russian officials considered Japan an upstart nation that would certainly not risk armed conflict with an established European power. When asked about the possibility of war with Japan and what it would take to combat that threat, the Russian foreign minister replied dismissively: “One flag and one sentry. Russian prestige will do the rest.” When it had become apparent that Russian stalling tactics would cause the talks to drag on indefinitely, the Japanese formally declared war on February 10, 1904. Two days prior to that, the Japanese launched a sneak attack against the Russian Pacific Fleet anchored at Port Arthur. While the audacious attack achieved only limited success, damaging two battleships and a cruiser, it set the tone for the remainder of the war. The badly shaken Russians refused to commit the balance of their naval power. Russian ships remained sheltered inside the harbor at Port Arthur, protected by the large guns of their shore batteries.

Admiral Heihachiro Togo, the Japanese commander during the Port Arthur engagement, realized that to achieve final victory it would be necessary to negate Russian naval power in the Far East once and for all. To facilitate that day of reckoning, the Japanese must first achieve success on land. Leveraging their advantages of shorter supply lines and combat experience gained during the war with China, the Japanese First Army crossed the Yalu River into Manchuria in May 1904, easily overwhelming the Russian defenders. Meanwhile, the Japanese Second Army landed on the Liaotung Peninsula, 40 miles northeast of Port Arthur, and linked up with the Japanese Third and Fourth armies to encircle the port in a ring of bayonets. A series of Japanese victories followed in central Manchuria later that year, and Port Arthur finally capitulated in January 1905.

A major consequence of the fall of Port Arthur was that the Japanese could train their heavy guns from the surrounding heights on the Russian ships cowering in the harbor. In short order the entire Russian Pacific Fleet was destroyed. Still, the Russian Army had not been withdrawn from Manchuria. Its numbers continued to grow, while Japan’s ability to finance a protracted war was being stretched thin. In February and March, the massive Battle of Mukden ended in a Japanese victory after combined casualties of more than 150,000. Given the probability of a continuing stalemate on land, the Japanese high command realized that the decisive battle of the war was destined to be fought at sea. For Japan, time was of the essence. Even before the fall of Port Arthur, Russian Czar Nicholas II had committed his Baltic Fleet to sail 18,000 nautical miles around the globe in an attempt to join what remained of the Pacific squadron and fight it out with the Japanese Navy in its home waters.

The news that a formidable Russian naval force had set sail presented both great opportunity and tremendous risk for the Japanese. Victory in all likelihood would mean a swift conclusion to the war and favorable terms for Japan. Defeat, while unthinkable, would relegate Japan to second-class status among the world’s nations and leave the proud country a vassal of the Russian Bear. When the Russian fleet, now renamed the Second Pacific Squadron, appeared through the mist on the morning of May 27, 1905, in the narrow Strait of Tsushima between Korea and the Japanese home island of Kyushu, Admiral Togo ordered a message signaled to his forces that was consciously reminiscent of Lord Nelson’s famous exhortation to the British fleet at Trafalgar, almost exactly a century before. “The fate of the empire depends upon the outcome of this battle,” Togo exhorted. “Let every man do his utmost duty.” The die was cast for the most decisive naval engagement since Nelson’s victory in that other strait—Gibraltar—100 years earlier.

On paper, the Russian Baltic Fleet was more than a match for Togo. In reality, there were stark contrasts between the opposing navies. A veritable colossus on land, the Russian Army commanded the respect of any rival. The navy, however, on the eve of war with Japan, had been allowed to deteriorate both in the quality of its warships and its combat efficiency. While there were competent officers in the naval cadre, there were also those who had benefited from political cronyism or aristocratic connections and were completely unfit for command. Many of the sailors were poorly trained peasants with limited experience and, in many cases, little love for the Czarist regime. Admiral Zinovi Rozhdestvensky, who led the Baltic fleet, was a capable if somewhat high-strung commander, but he had never before been in combat.

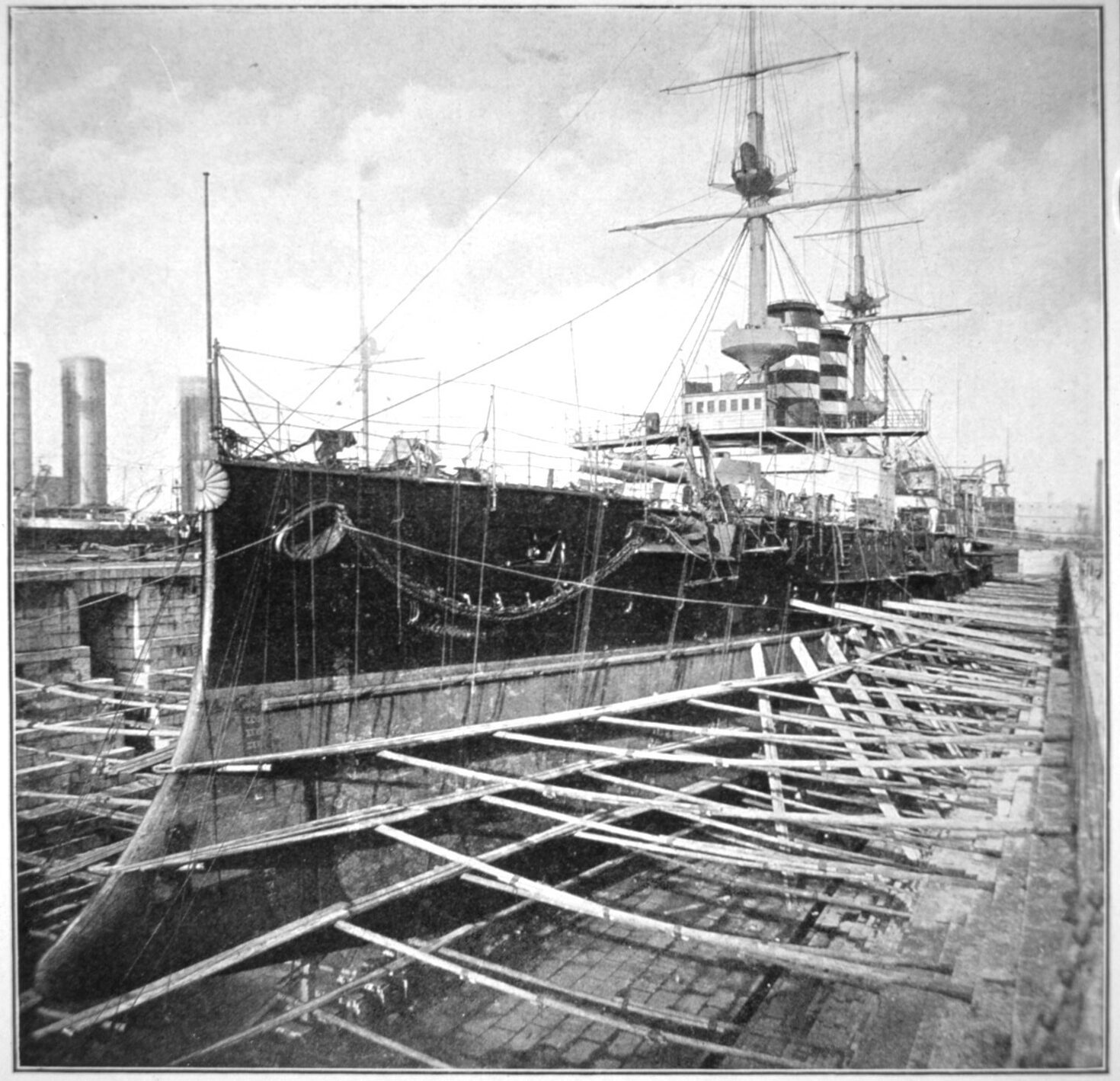

Organized in five divisions, the fleet under Rozhdestvensky’s command had weighed anchor from the port of Reval on the Gulf of Finland on October 15, 1904. The first division included the four new battleships—Alexander III, Borodino, Orel, and the admiral’s flagship Suvorov—each weighing 15,000 tons with main armament of four 12-inch guns complemented by 6-inch secondary cannons. The modern battleship Oslyabya led the second division, but the quality of the fleet fell off considerably from there. Two elderly 10,000-ton battleships, Navarin and Sisoi Veliky, each armed with 12-inch guns, and the slow, 6,000-ton armored cruiser Nakhimov, which was more than 20 years old, were hardly fit for use in the coming battle. The remaining divisions consisted of eight armored cruisers and various light cruisers and destroyers.

The fleet commanded by Togo, on the other hand, while outnumbered, included four battleships that were less than a decade old. While some of the warships had been built in the navy yards at Yokosuka and Kure, the Japanese had also contracted with the British to construct the capital ships and a number of their cruisers. Togo’s flagship, Mikasa, was joined by two other battleships, Asahi and Shikishima, each displacing 15,500 tons, with four 12-inch guns and multiple 6-inch secondary armament. The older 12,500-ton battleship Fuji was also armed with 12-inch main batteries. The Japanese also employed a pair of fine new 7,700-ton armored cruisers, Kasuga, with a 10-inch gun forward and a pair of 8-inch guns aft, and Nisshin, with four 8-inch mounts. These were augmented with a number of light cruisers, destroyers, and torpedo boats.

Besides the comparative newness of its fleet, the Japanese enjoyed several other distinct advantages at Tsushima. In general, their ships were considerably faster than their Russian adversaries, and their armament was first class. Russian guns were still fired manually by lanyard, while Japanese fire control was electric, substantially improving both accuracy and rate of fire, which could spell the difference between victory and defeat in a heavy engagement. While the Russians were using advanced armor-piercing shells, the Japanese purchased most of the ammunition from the British. The British shells were more antiquated and were not capable of deep penetration before exploding, but the Japanese compensated for this shortcoming with shimose, an explosive charge that shattered the shell casing into thousands of deadly shrapnel splinters, devastated a ship’s superstructure, and produced clouds of noxious smoke. Large-caliber Japanese shells, particularly the 12-inchers, were heavier than those the Russians fired—850 pounds versus 732 pounds—providing greater muzzle velocity and a flatter trajectory.

The readily adaptable Japanese possessed other advantages as well. When the most advanced Marconi wireless equipment became available, the Japanese quickly purchased it and installed it on the majority of their vessels. The hidebound Russians, by contrast, had opted against the communications upgrade. In addition, the Japanese were defending home waters, well known to them, and the Russian—both men and ships—were exhausted after a marathon seven-month-long voyage around the world. But perhaps the greatest advantage for the Japanese was the high level of esprit de corps within their naval ranks. Overall training, gunnery, and seamanship were superb. Such a premium was placed on perfection that fleet exercises were actually conducted using live ammunition. Isoroku Yamamoto, a young naval cadet who would rise to prominence during World War II, recalled an experience in which his class was required to swim the cold, icy channel between two islands off the coast of northern Japan. Large sharks inhabited the waters, and a substantial number of cadets failed to reach the opposite shore.

For the Russians, simply managing to sail such a great distance was an amazing logistical feat, particularly considering the command challenges faced by Rozhdestvensky. Even before his fleet embarked, the admiral was confronted with the interference of the ruling navy board. With little appreciation for what lay ahead, the board ordered Rozhdestvensky to add several slow, antiquated warships to the squadron. When he protested, the board finally relented. Two months later, however, these same ships were dispatched and eventually joined him. Painfully aware of the lack of training among his crews, Rozhdestvensky’s only option was to train vigorously during the voyage. When completely assembled, the Russian fleet numbered more than 40 ships, including non-combatant vessels. Given the wide variance in speed capabilities, the ships were strung out for miles. The government was required to charter 70 colliers from Germany’s Hamburg-Amerika Line, and the mechanical reliability of the coal fired ships, particularly the older vessels, was questionable from the outset. At least three ships were deemed unfit for duty and ordered back to port after the journey began. “Our long voyage was a prolonged and despairing struggle with boilers that burst and engines that broke down,” wrote one of the frustrated captains. “On one occasion, practically every ship’s boilers had to be relit in the space of 24 hours.”

During the voyage, the Russian ships and crews were subjected to extremes of heat, cold and stormy weather. For the sailors, periods of backbreaking work were punctuated by hours of boredom. While traversing tropical areas, those crewmen responsible for the boilers and engines labored in sweltering temperatures that easily topped 100 degrees. Sailing across the North Sea, the Russians turned south and called at the port of Vigo in Spain. At Tangier on the coast of North Africa, a small squadron was detached to pass through the Suez Canal, while the bulk of the fleet continued south to Dakar, Senegal, and several other stops along the coast of West Africa. Rozhdestvensky rounded the Cape of Good Hope and reunited with the other group in Madagascar in January. From there, the Russians crossed the Indian Ocean, anchoring at Cam Ranh Bay and Van Fong in Indochina in April before the last leg of their journey and a final rendezvous with destiny.

The most bizarre event during the voyage occurred during the transit of the North Sea as the Russian fleet sailed through the Dogger Banks, a heavily trafficked and well- known fishing ground. On the foggy night of October 24, the transport vessel Kamchatka was sailing some distance astern of the warships. For no apparent reason, the ship wired the rest of the fleet that she was under attack by torpedo boats. The relative quiet was shattered by flashes of gunfire, and soon the entire Russian squadron was firing wildly in the darkness. There actually were unknown vessels in the area, but the phantom torpedo boats were in fact trawlers of the British owned Hull fishing fleet. In the confusion, the Russians began shooting at on one another, and the cruiser Aurora took five hits from friendly fire. One trawler was sunk, and several others were damaged. The hair-trigger response by the Russians was undoubtedly fueled by a rumor that the Japanese had positioned torpedo boats along the route. The jittery Russians were roundly criticized in the world press, and their government later paid reparations to the British.

Although Rozhdestvensky had intended to join forces with the Pacific Squadron, he received the disheartening news of the fall of Port Arthur while in Madagascar. He was also informed of civil unrest at home, which signaled the beginning of the revolution of 1905. With Port Arthur in Japanese hands, the only option for Rozhdestvensky was to sail for the Russian port of Vladivostok to the north. Togo realized his adversary’s predicament and considered the possible Russian routes for reaching the safety of Vladivostok. One choice was through the Tsugaru Narrows, which lay between the home islands of Honshu and Hokkaido. The Japanese, however, had already sown mines there, and the Russians would be vulnerable as we;; to attacks by torpedo boats stationed at nearby Japanese bases. A second northern route was through the La Perouse Strait between Hokkaido and Sakhalin Island. Narrow and approachable only after negotiating a tangle of reefs in the nearby Kurile Islands, this route was dismissed by Togo.

The Japanese commander correctly judged that the Russians would choose the southernmost route through the Korean Straits, sailing west of the home islands and into the 100-mile-wide channel separating Japan from Korea. In order to block the enemy’s path, Togo moved his battleships and their escorts to Masan, on the southern coast of Korea, and stationed a cruiser force at Osaki on the island of Tsushima, which was located squarely in the center of the strait. He also deployed cruisers, fishing vessels and armed merchant ships as pickets to provide early warning of the Russians’ approach. This last precaution soon paid huge dividends. At approximately 2:45 on the fog shrouded morning of May 27, the merchant ship Shinano Maru was on patrol 150 miles south of the entrance to the Korean Straits. Visibility was poor, just a few hundred yards at best. Captain Ki Narukawa peered through his binoculars to catch any glimpse of the Russians, whom he knew must be close by. Suddenly, a twinkle of red-and-white lanterns caught his eye. Nearly two hours later, Narukawa had maneuvered close enough to see that the lights were dangling from the masthead of a Russian hospital ship that unaccountably had failed to adhere to Rozhdestvensky’s absolute blackout order. Narukawa snapped off a short wireless message: “Enemy fleet in sight in square 203. Is apparently making for the eastern channel” Minutes later, Togo issued orders for his ships to get underway and cabled the emperor in Tokyo: “I have just received news that the enemy fleet has been sighted. Our fleet will immediately put to sea to attack and destroy him.”

Shortly after dawn, the Japanese cruiser Idzumo began shadowing the Russians as they proceeded northward. At various times other cruisers drifted in and out of the mist amid the growing swells of the angry sea, sometimes provoking the Russians to lob a few shells in their direction but not bringing on a general engagement. The main body of the Japanese fleet, with its heavy guns, was on the way. Togo sailed out of Masan just before 6 a.m., with his flagship Mikasa leading the line, followed by his three other battleships, Shikishima, Fuji and Asahi, and the cruisers Kasuga and Nisshin. His original plan to engage the Russians initially with swarms of torpedo boats had to be scrapped. The weather was too rough for them to operate until later in the day. Instead, it was apparent that the first major contact between the opposing forces would be the clash of capital ships. The Japanese commander made haste for a station adjacent to the island of Okinoshima.

When the Russian fleet began to pick up increasing Japanese radio chatter, Rozhdestvensky knew that his force had been discovered. At first light, the shadowing Japanese cruisers confirmed his assumption. Sometime later, he ordered his ships to move from line ahead to line abreast in preparation for the coming engagement. This required the captains of the four leading battleships to turn in succession 90 degrees to starboard, followed by a simultaneous 90 degree turn to port. Rozhdestvensky had probably hoped to position himself to execute the classic naval combat maneuver known as “crossing the enemy’s T.” However, poor Russian seamanship caused the complex maneuver to be botched, and the ships formed two unequal columns line ahead. Rolling waves, some four feet high, buffeted both forces, while mist and fog made identification of friend or foe difficult at times. Finally, around 1:15 p.m., Togo spotted his shadowing cruisers, which had been skillfully commanded by Admiral Shigeto Dewa. Just a few minutes later, the black hulls of the Russian battle fleet began appearing on the horizon. Curiously, the Russian color scheme included funnels painted bright yellow with a black strip covering the top quarter. These would prove to be excellent aiming points for the Japanese gunners once the battle was joined.

When Rozhdestvensky saw the Japanese approach, he again attempted to reorganize his line. For a second time, the maneuver was executed improperly. Two of the battleships, Oslyabya and Orel, narrowly avoided a collision. Meanwhile, Togo decided to take a calculated risk of his own. Confused by the odd Russian alignment, he intended to make the most of it. His ships were at a slight disadvantage downwind of the Russians, and his gunners would have difficulty tracking their targets in the swirling spray if he continued on his present course which would carry him parallel to the enemy and in the opposite direction. Undaunted, Togo issued a bold order—his ships were to turn to port in succession, each executing the turn at the same point. The maneuver was extremely dangerous because the Japanese ships would be exposed to Russian fire for a period of time while their own guns could not be brought to bear. However, once the maneuver was completed, the Japanese would be crossing the Russian T, bringing their heavy broadsides slamming into the enemy while only a few of the forward guns on the Russian ships could reply.

The experienced Japanese sailors executed the turn with absolute precision, but for several minutes they ran a gauntlet of Russian shells. Mikasa turned first, and at 2:08 p.m., the battle began in earnest as Suvorov fired a 12-inch salvo at the enemy flagship. The ranging Russian gunners’ shells came within 20 yards of Mikasa, raising the ship’s stern from the water and sending huge geysers skyward. During the first five minutes of the battle, Mikasa was hit a dozen times, two of the shells causing extensive damage. One hit destroyed the ship’s compass and the bridge ladder, wounding 15 officers. Togo himself narrowly avoided serious injury, but showed no emotion as the fight began. A second shell slammed into one of the battleship’s 12-inch turrets. Other Japanese ships were also damaged, the cruiser Asama falling out of line after taking three hits near the stern and the cruiser Yakumo losing her forward gun turret to a direct hit from the Russian battleship Nikolai I. Rozhdestvensky had been ill served by his subordinates. Had his orders been executed properly, the damage inflicted on the turning Japanese line would undoubtedly have been much greater.

When the Japanese ships came out of their turn, which had seemed agonizingly slow, their gunners began ranging the Russian warships from a distance of only 5,000 yards. By 3 p.m., the Japanese were completely across the Russian T. Concentrated and accurate fire set the Suvorov ablaze from stem to stern. A shell struck the flagship’s bridge, killing six sailors and seriously wounding Rozhdestvensky, who fell unconscious and was later evacuated to a destroyer. Had not been rendered hors de combat, Rozhdestvensky might have salvaged the situation while the faster Japanese fleet, making 15 knots, continued its eastward course. A turn to port could have put the Russians in position to hammer the tail of the Japanese line from the rear. Instead, the confusion resulted in the entire Russian line continuing to starboard. Suvorov’s helm jammed, and the doomed battleship began turning in circles. A sitting duck, she was pounded in a crossfire by Togo’s battleships and several Japanese cruisers and finished off by Japanese torpedo boats. Simultaneously, Oslyabya, at the head of the second Russian line, had taken such tremendous punishment that she capsized and sank an hour after the fighting began.

Following Suvorov in line, Alexander III began to turn in a circle with the flagship. When the battleship’s captain finally comprehended what was happening, he ordered a course back to the east and then to the north. Togo responded with a pair of 90 degree turns by the main body of his battleships and cruisers, herding the hapless Russians back into the Japanese gunsights and cutting off their route of escape toward Vladivostok. Third in line, the battleship Borodino, had been burning furiously since early in the one-sided contest. Briefly, the battered Russians found refuge in a fog bank, but about 4 p.m., they were spotted once again. During the same exchange that reduced Suvorov to a smoking ruin, Alexander III was pounded and drifted out of the fight with fire gushing amidships. While his cruisers stalked the Russian transport ships to the south, Togo allowed the Russians, with the defiant Borodino in the lead, to turn southward as well. Rather than following immediately, he took the opportunity to move northward, assessing his own damage and resting his tired crews.

Less than two hours later, Togo regained contact with what was left of the main Russian fleet. With her fires somewhat under control, Alexander III had once again assumed a position at the head of the Russian column. Within a short time, however, the ship was once again blazing and listing heavily to port. As a huge fire raged near the conning tower, sailors crowded into the battleship’s forecastle. Abruptly, the ship rolled over and sank, trapping hundreds of sailors beneath her. Only four of her complement of 830 men survived. As Suvorov slipped beneath the waves and Alexander III was in her death throes, the Japanese began to concentrate their fire on Borodino and the nearby battleship Orel, which was set ablaze. With daylight fading, Togo decided that he would reorganize his force. He ordered his ships to disengage and assemble early the following morning near Matsushima. Just before Togo’s order to cease fire, the battleship Fuji loosed the day’s last salvo of 12-inch shells at the stricken Borodino. At least one of these penetrated the Russian battleship’s magazines, and she virtually vaporized in a horrific explosion. A single sailor survived the disaster.

Dewa’s cruisers, joined by a second squadron, had taken hits from their Russian adversaries, which guarded the transports. Kisagi was seriously damaged and withdrew from the fight, while Naniwa and Matsushima were also pounded. In exchange, the Russian cruiser commander, Admiral Oskar Enkvist, tried to direct damage control efforts aboard his flagship, Oleg, and Zhemchung, both of which now were on fire. Three transport ships were sunk, and the two Russian hospital ships captured. Eventually, Enkvist veered out of the fight and retired southward to Manila, where American authorities interned Oleg, Zemchung and Aurora, along with their crews.

With Rozhdestvensky still unconscious aboard the destroyer Dedovy, command of the shattered Russian fleet devolved to Admiral Nikolai Nebogatov aboard the battleship Nikolai I. In a vain attempt to resume a course for Vladivostok, Nebogatov ordered his fleet to turn from its southeast heading and take a northerly course. In the darkness, dozens of Japanese torpedo boats and destroyers lay in wait. Several Russian ships were unable to join up with Nebogatov, and they bore the brunt of the nocturnal attacks. The cloak of darkness failed to save the Russians from further calamity. For several hours, the small Japanese craft dashed to within 100 yards to launch torpedoes, frustrating the Russian gunners, who could not depress their heavy weapons low enough to return fire. Sisoi Veliky took a torpedo aft and sank sometime after daylight near the island of Tsushima, while four torpedoes smashed into Navarin, which carried all but four of her crew to the bottom around 10 p.m. Two Japanese torpedo boats had been sunk and six damaged in the melee.

The Russian cruisers were luckless as well, with the damaged Svetlana cornered by three Japanese cruisers the next day and sunk with no survivors after a heroic three-hour fight. Nakhimov and Monomakh were both damaged and scuttled after daylight to prevent their capture. The old cruiser Dmitri Donskoi sank off Matsushima after fighting for several hours with Japanese cruisers and destroyers, damaging several of them. The next morning, Nebogatov, with only the battleships Nikolai I and Orel and the aged armored defense ships Apraxine and Seniavine, found himself hemmed in on three sides by Japanese cruisers and Togo’s main force again moving across the Russian T. The Japanese stood out of range of the most powerful remaining Russian guns and began shelling the survivors from 12,000 yards. Nebogatov recognized the futility of continued resistance. He ordered his flag lowered to half staff aboard Nikolai I and then hoisted the signal flags XGH, asking for a parlay with the Japanese. As the shelling continued, other Russian vessels began to strike their colors. Some ran the Japanese rising sun emblem up their masts in surrender. Finally, Togo relented and ordered the firing to stop. “I am an old man of 60,” Nebogatov reportedly told his crew before leaving Nikolai I to meet with the Japanese commander. “I will be shot for this, but what does that matter? You are young, and it is you who will one day retrieve the honor and glory of the Russian navy. The lives of the 2,400 men in these ships are more important than mine.”

Only the cruiser Izumrud and two destroyers escaped the clutches of the Japanese and reached Vladivostok. Scattered remnants of the Russian fleet were rounded up, and the wounded, bed-ridden Rozhdestvensky became Togo’s prisoner. For the Russians, Tsushima had been a disaster of epic proportions. They had lost 34 ships, 4,830 dead, 5,917 wounded and captured, and nearly 2,000 interned. Many high-born sons of the Russian aristocracy found an icy grave in the East China

Sea. The Japanese, by comparison, lost only three torpedo boats, 110 killed and 590 wounded. The totality of the Japanese victory stunned the world, and Togo became a national hero. The normally reserved Japanese people danced in the streets when they heard the news.

Although the Russian and Japanese armies still confronted one another on land, Japan was the undisputed master at sea. The sheer magnitude of the victory was enough to bring the shocked and despondent Russians to the negotiating table. American President Theodore Roosevelt offered to mediate the peace talks, and the Treaty of Portsmouth, ending the Russo-Japanese War, was signed on September 5, 1905, in New Hampshire. Under the terms of the treaty, Russia recognized the preeminent influence of Japan in Korea and ceded Port Arthur and a second port city, Dairen, on the Liaotung Peninsula to the Japanese. The victors also received the southern half of Sakhalin Island and other concessions, including the right to use railroad lines in southern Manchuria.

With the demise of Russian naval power in the Far East, a number of nations began to raise questions about continued Japanese expansion. Roosevelt was among those who voiced concerns. A year after the end of the war, he wrote to a friend: “In a dozen years the English, Americans and Germans, who now dread each other as rivals in the trade of the Pacific, will each have to dread the Japanese more than they do any other nation. If we try to treat them as we have treated the Chinese, and if at the same time fail to keep our navy at the highest point of efficiency and size—then we shall invite disaster.” Roosevelt’s words proved prophetic. Their victory at Tsushima did much to bolster the confidence of Japan’s military and promote their notion of invincibility. Less than half a century later, this myth would lead them to mount another sneak attack—at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii—and ultimately envelop them in the ruinous inferno of World War II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments