By Mike Phifer

The bloody fight for the Reichswald, according to Lieutenant General Horrocks, was a soldiers’ battle “fought by the regimental officers and men under the most ghastly conditions imaginable.”

“We had so damn many guns, we didn’t have enough real estate to put them down on,” quipped Brigadier Stanley Todd, commander of the 2nd Canadian Corps Artillery. “We had to put two batteries in every position,” he added. More than 1,000 guns lined the border between The Netherlands and Germany near Nijmegen, their barrels aimed menacingly at the enemy-occupied Reichswald Forest.

At 5 a.m. on February 8, 1945, the artillery thundered, muzzle flashes piercing the gray morning sky. Adding to this fury of noise and high explosives being hurled at the Germans were medium machine guns, tanks, mortars, anti-tank guns and waves of rockets from the 1st Canadian Rocket Battery. Lieutenant Howard Powell of the Calgary Highlanders watched in awe as this latter unit fired a 12-projector salvo at a farm and a grove of trees and the “place just disintegrated, all in one smack.”

The German soldiers could do nothing but endure the pounding, as previously registered strongpoints were smothered in a tornado of fire. Mercifully, the guns fell silent at 7:40 a.m. Smoke shells then landed along the front in an attempt to trick the German guns into returning fire and revealing their positions. Most of the German gunners that had not already been knocked out didn’t take the bait. But about 20 positions, one battery and the rest mortars, did fire back and were quickly located and wiped out as the bombardment continued 10 minutes later.

For another two-and-half hours or so the pounding continued to smother the German positions. At 10:29 a.m., yellow smoke-shells signaled that in one minute thousands of Scottish, Welsh, and Canadian troops would attack. As the artillery began laying down a creeping barrage, lumbering tanks and four divisions of infantry moved toward Reichswald Forest and German soil.

Almost three months earlier the 1st Canadian Army took over the Allied line along the Meuse or Maas River in the Nijmegen Salient, Netherlands. The Canadian army was under the command of General Harry Crerar and was part of the 21st Battle Group commanded by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. This battle group consisted of the 1st Canadian Army and the 2nd British Army and held the northern end of the Allied 600-mile line that stretched from the North Sea to Switzerland.

By late 1944, the Allies were focused on getting over the Rhine River and into Germany. But first they had to deal with the Nazi forces in the Rhineland, a swath of land 20-30 miles wide that lay between much of the Allied line and the Rhine River. The Maas and the Roer Rivers flowed through the Rhineland, creating natural obstacles. The Germans had also added the formidable Siegfried Line or “West Wall” as they called it.

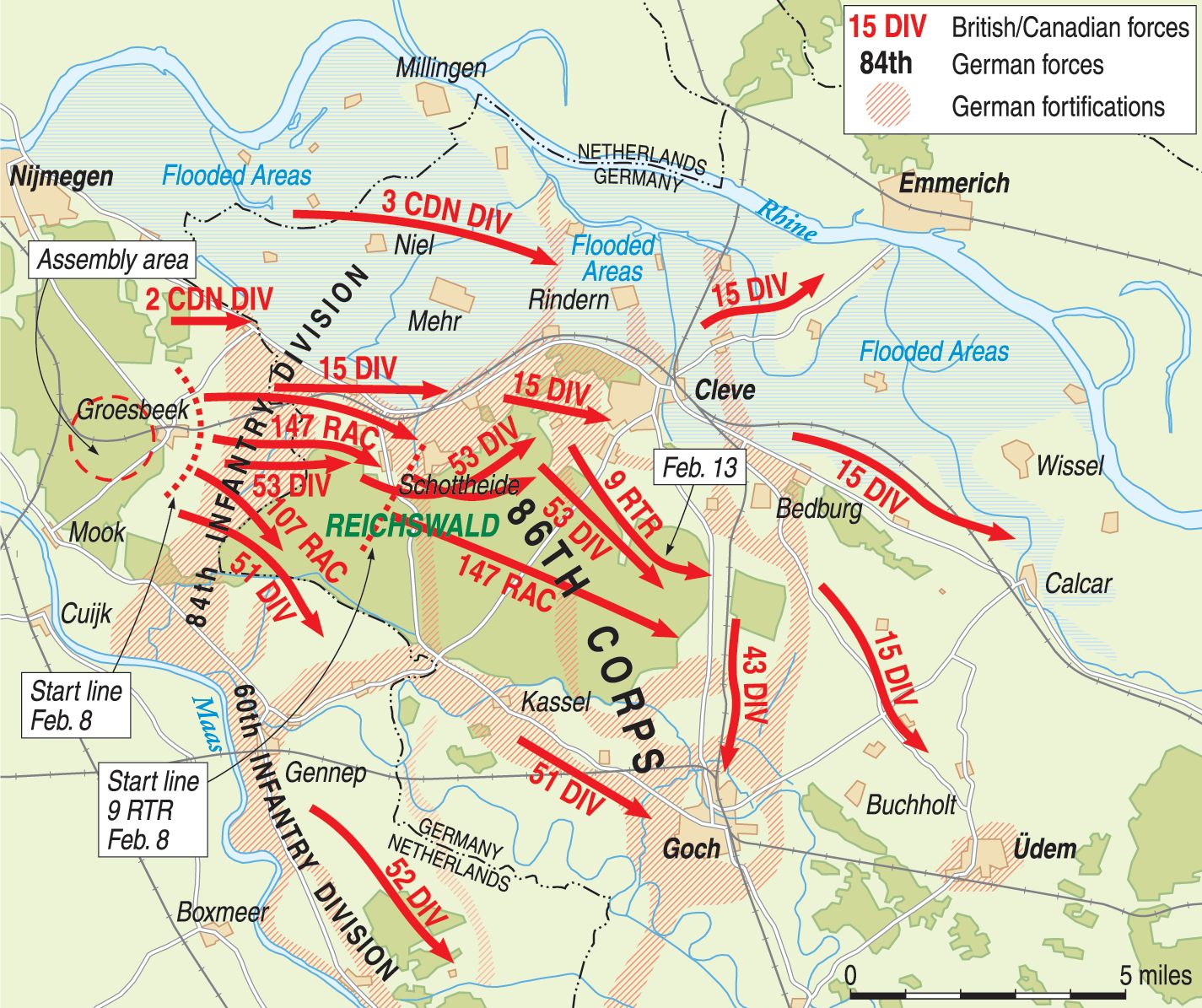

In talks with Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, commander of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, Montgomery proposed a two-pronged attack into the Rhineland to secure the west bank of the Rhine River. The northern attack, launched southward from the Nijmegen area between the Maas and Rhine Rivers under the command of the 1st Canadian Army, would be called “Operation Veritable.” The southern attack, called “Operation Grenade,” would be carried out by American forces across the Roer River.

Both forces would cross the Rhineland and converge near Wesel, along the Rhine River. The Germans on the west side of the Rhine would be forced to fight and be wiped out, or retreat across the river. By March, the Allies would then be in a position to cross the Rhine.

Operation Veritable was scheduled tentatively for New Year’s Day 1945, but everything changed on December 16. That day, three German armies smashed into the Ardennes Forest, catching American forces there by surprise. Brutal fighting raged into January before the situation was restored. It would not be until January 21 that Eisenhower assigned Lt. Gen. William Simpson’s 9th Army of the 12th U.S. Army Group to Montgomery’s command for Operation Grenade. That same day, Montgomery set February 8 for the launch of Operation Veritable. Eventually February 10 was the date set for Operation Grenade.

The 1st Canadian Army’s sector was a bustle of activity preparing the massive logistics for Veritable. Adding to the congestion of the operation’s crowded start area was the arrival of the British 30th Corps, which was assigned to the Canadian army. Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks, commander of the 30th Corps, was responsible for carrying out Operation Veritable. Temporarily attached to his corps was the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Division giving him overall a strength of about 200,000 troops.

fitted with a flamethrower and towed a 400-gallon armored fuel tank for it.

To help keep the enemy unaware of the coming operation, officers of the 30th Corps who reconnoitered the front lines were ordered to travel in Canadian vehicles and wear Canadian uniforms as they were of darker khaki than the British ones. The vast amount of supplies and ammunition were moved up at night near their final positions and were concealed in farmyards, haystacks, simulated hedgerows and barns, among other places. The large concentration of artillery south and east of Nijmegen were camouflaged, while at the same time obvious “dummy” gun positions visible to German patrols were established. These “dummy” guns would be switched for real ones shortly before the operation began. Six divisions moved up in the darkness to where assembly lines were hidden in dugouts, schoolhouses, assembly halls and factories. Nearby fields, meanwhile, overflowed with camouflaged tanks, armored vehicles and anti-aircraft guns.

Canadian engineers worked around the clock to improve the roads and build new ones along with bridges to allow the vast number of troops, equipment and material to get to the front. Conditions were to get worse when the weather turned milder and a pounding rain began in early February. “The tide’s in!” joked soldiers of the Canadian Scottish Regiment (Canscot) when they woke up on the morning of the 7th to find the surrounding fields submerged. The Germans had blown holes in the Rhine’s winter dike, allowing water to rush into the already drenched lowlands. On the eve of Operation Veritable, half of the coming battlefield was under five feet of water and the other half was a quagmire of mud.

This Allies began with a bottleneck only six miles wide between the Maas and Rhine Rivers. Looming sinisterly at this point was the Reichswald, a 32-square mile state forest divided into blocks separated by “rides” or narrow tracks. Two paved roads cut through Reichswald from the north converging at the town of Hekkens midway along the southern edge of the forest.

To defend this area the Germans had constructed three defensive belts. The first belt ran from the town of Wyler, located on the road to Cleve, along the western face of Reichswald then southward eventually passing through Gennep and down the east bank of the Maas River. This line consisted of trenches, anti-tank ditches, roadblocks, dug in anti-tank guns, minefields and was further strengthened with farmhouses and villages converted into strongpoints.

The second defensive belt was part of the Siegfried Line. Construction of the line in this area had not been completed, causing Maj. Gen. Heinz Fiebig commander of the 84th Infantry Division to comment that this section of the famous line was “a haphazard series of earthen dugouts.” Besides trenches and anti-tank ditches, the line was strengthened with about 70 or so concrete shelters and pillboxes. With the northern end of line being located about three miles to the rear of Wyler, the Siegfried Line ran through the Reichswald then skirted the southern edge of the forest. There it turned south and passed through Goch and continued southward.

Six miles east of Reichswald a third defensive belt stretched from Rees along the Rhine southward in front of Hochwald Wood to Geldren. The Allies called this area of trenches, minefields and anti-tank ditches the “Hochwald Layback.”

Holding Reichswald was Fiebig’s 84th Infantry Division numbering about 10,000 troops. This division narrowly escaped the Falaise Pocket during the end of the Normandy campaign. It had been reformed and refitted but had suffered heavy casualties during Operation Market-Garden. In the division ranks being held in the rear area were the 276th Magen (stomach) Battalion made up of troops with digestive problems and the Sicherungs Battalion Munster, consisting of older men who usually guarded static installations.

Fiebig was recently bolstered by the well-equipped 2nd Parachute Regiment, 2nd Parachute Division, numbering about 2,000 troops. Also supporting Fiebig were 36 self-propelled guns of the 655th Heavy Anti-tank Battalion and 100 artillery pieces. The 84th Infantry was part of Gen. Erich Straube’s 86th Corps which along with the 2nd Parachute Corps and the 47th Panzer Corps made up the 1st Parachute Army under Gen. Alfred Schlemm tasked with holding the northern part of the Rhineland.

Fiebig was recently bolstered by the well-equipped 2nd Parachute Regiment, 2nd Parachute Division, numbering about 2,000 troops. Also supporting Fiebig were 36 self-propelled guns of the 655th Heavy Anti-tank Battalion and 100 artillery pieces. The 84th Infantry was part of Gen. Erich Straube’s 86th Corps which along with the 2nd Parachute Corps and the 47th Panzer Corps made up the 1st Parachute Army under Gen. Alfred Schlemm tasked with holding the northern part of the Rhineland.

While the 30th Corps prepared to smash the German defenses, they received maximum Allied air support. Bridges, ferries and enemy supply dumps were targeted as were road and rail bridges at Wesel. On the night of February 7/8 Goch and Cleve were shattered in a heavy bombing raid. It was hoped that, by destroying Cleve and its road and rail lines, that the Germans would have difficulty bringing in reinforcements.

As the fires from the bombing of Cleve created a crimson glow in the distance, Horrocks climbed half way up a tree to a small platform. In the early gray morning of February 8, Horrocks had a good view over most of the battlefield. By this time British and Canadian guns were hammering the German positions in Reichswald and surrounding areas. “The noise was appalling, and the sight was awe-inspiring,” Horrocks later wrote.

Half a million shells pounded the enemy in what was one of the largest British artillery barrages of the war. “There was no scope for cleverness,” Horrocks said of the narrow front before his 30th Corps. “I had to blast my way through.”

Blast he did, as the severe artillery pounding initially did its job. Crerar would later report that “resistance offered by a dazed and shaken enemy proved to be a lesser handicap than the appalling conditions on the ground.” On Horrocks’ left, the 3rd Canadian Division did not join in with the infantry and armor that advanced into the Reichswald and surrounding area. They were not scheduled to attack until 6 p.m.

To their right was the 2nd Canadian Division where two of its brigades had been holding the front line, through which the Scottish and Welsh divisions, along with the armor, now passed. Only the 5th Brigade of the 2nd Canadian Division would be joining the attack and their objective was to clear a small piece of land south of the Nijmegen-Cleve road near Wyler. This was the northern anchor of the German’s first defensive line and its capture was critical for the rapid advance of the neighboring 15th Scottish Division.

Supporting the 5th Brigade was a squadron of tanks from the 13/18th Hussars and a squadron of Crab/Flail tanks from the 79th Armoured Division. These Flail tanks had a rotating drum with long chains attached to its front that were used in clearing mines. The Flails and other unusual tanks from the 79th would be attached to the other attacking units as well.

Hugging the creeping barrage, the Regiment de Maisonneuve of the 5th Brigade captured its objective of Den Heuvel along with a number of shell-shocked Germans by 11:23 a.m. The Calgary Highlanders, meanwhile, had a tougher time.

Nearing the hamlet of Vossendall “A” Company came upon a minefield. The mines were scattered about on the surface and as the troops began to step around them, they quickly discovered to their horror other mines were buried just below the surface. To add to their misery mortar shells began to crump around them and vicious machine gun fire opened up from the edge of Vossendall. In a handful of minutes 28 men were killed or wounded and the rest pinned down in the minefield.

Lance Corporal Robert Allan McMahon got clear of the minefield and took out the enemy machine guns. He captured 22 German troops and an officer who he had to punch into submission when he realized McMahon was alone. McMahon forced e the Germans go into the minefield to carry off the Canadian casualties. The Calgary Highlanders then pushed on to their objective of Wyler, which they captured at 6:30 p.m., along with 322 prisoners. Having secured their objective, the 2nd Canadian Division was withdrawn from the battle for the time being.

The 15th Scottish Division to the Canadians right moved forward on a two-brigade front with 46th Brigade on the right and 227th on the left. Following behind these two brigades was the 44th Brigade. Supporting the infantry were tanks from the 6th Guards Tank Brigade and two regiments of 79th Armoured Division including Flails. Mines and mud were trouble for the 15th Scottish Division, whose object was to breach the Siegfried Line north of the Reichswald and take the Materborn feature—the high ground that overlooked Cleve.

Flails opened a gap in the minefields on the right, but many bogged down in the mud. The Scots pushed on but were behind schedule. The narrow tracks the armor were following became impassable due to flooding and the pounding rain. By afternoon only one track was still usable, slowing the armor. In the growing darkness the 46th Brigade cleared the village of Frasselt, while the 227th Brigade took Kranenburg.

The 44th Brigade was tasked to move forward and smash through the Siegfried Line, but the single track slowed down its supporting Special Breaching Force of nearly 300 armored vehicles. It proved to be a nightmare for the men working through the night to get some order of the traffic chaos. Bulldozers managed to build a detour for the armor, but it would be the early morning of February 9 before the exhausted 46th Brigade would be in position to launch an attack against the Siegfried Line.

The 53rd Welsh Division, meanwhile, to the right of the 15th Scottish Division had the task of clearing a good portion of the Reichswald Forest. Leading the attack on a narrow front was the 71st Brigade supported by squadrons from the 34th Armoured Brigade. There was little enemy resistance at first, but as elsewhere, the tanks bogged down in the mud. The exception were the Churchill tanks which had broader tracks and managed to keep up with the 71st Brigade.

By 2 p.m. the 1st Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry had taken Brandenberg Hill. The 71st Brigade was soon in control of the northwest angle of the Reichswald Forest. In a cold incessant rain two battalions of the 160th Brigade, along with a squadron of Churchills, pushed deeper into the forest. By 2 a.m. they had broken through the Siegfried Line and had reached the Kranenburg-Hekkens road.

Attacking to the right of the 53rd Division and on the right of Horrocks’ front was the 51st Highland Division supported by squadrons of the 34th Armoured Brigade and elements of the 79th Armoured Division. Their objective was to clear the southwest corner of Reichswald and open the gap between the forest and the Maas River where the key Mook-Goch road passed through.

The advancing 154th Brigade quickly had three of its Black Watch officers killed by sniper fire. Bitter fighting soon raged as the Scots of the 154th Brigade attempted to root out determined troops of the recently arrived 122nd Grenadier Regiment, 180th Infantry Division of the 86th Corps holding little villages near the Reichswald. Flails, meanwhile, cleared a lane through a minefield up to an anti-tank ditch. There an engineer tank dropped a box girder bridge and a bulldozer ramped the ditch with rubble and anything else it could find. The bridge was usable by mid-afternoon, while another crossing was ready by late evening.

The 154th Brigade fought hard for FreudenBerg Ridge, its objective just inside the forest, until 4 a.m. the next morning. The 153rd on the division’s right flank, meanwhile, had its lead elements establish a position at the southernmost corner of the Reichswald around midnight.

At 6 p.m. the 3rd Canadian Division on Horrocks’ left, or northern, flank launched their watery assault. Their objective was to clear the area between the Nijmegen-Cleve road and the Rhine River, securing the left flank of the 2nd Canadian and 15th Scottish Divisions. As this area was mostly flooded a good part of the 3rd Division, dubbed the “Water Rats” for previous amphibious operations, would be attacking in Buffalos—amphibious tracked vehicles.

Aided by “artificial moonlight” which involved searchlights reflecting off low hanging clouds and a smoke screen, the Canadians attacked. The division’s 7th Brigade objective was the Quer Damm which blocked the line of advance. Here the Germans had defensive positions on either end of the partly collapsed mile-long dam. Having enough dry land to advance on, the Regina Rifle Regiment supported by the 13th/18th Hussars and a Flail tank captured the German defenses on the southern end of the dam. They pushed on a mile further east and captured the village of Zyffich, bagging 100 prisoners. The 8th Brigade, meanwhile, on the division’s left flank had secured the village of Zandpol and a dike near it.

The situation proved tougher at the enemy’s stronghold on the north end of the Quer Damm. Cruising in on Buffalos, the Canscots quickly captured enemy dugouts but soon encountered a defiant concrete pillbox spraying machine gun fire. After some delay the Canscots had a Buffalo move in and lay down covering fire from its 20mm and 50mm machine guns. A platoon section then managed to finally silence the troublesome pillbox.

Overall, the 30th Corps attack had gone well considering the rain, flooded terrain and churned up mud. They had taken 1,200 German prisoners and had mauled six enemy battalions. The next day the 30th Corps continued their attacks against the Germans and mud. Low hanging clouds and a hard rain grounded air support while the flood levels continued to rise.

The 3rd Canadian Division continued to capture villages over their flooded portion of the battlefield. The 51st Highland Division met tough resistance as the 153rd Brigade cut the road between Mook and Gennep, a village located along the Maas River. Elsewhere elements of the 152nd Brigade battled to within a couple of miles of Hekkens.

Meanwhile, the 53rd Welsh Division made good progress in the Reichswald. The 160th Brigade along with the 9th Royal Tanks pushed eastward a couple of miles toward the Stoppelberg high ground. There the 2nd Battalion of The Monmouthshire Regiment after sharp fighting took a key hill there. The 160th Brigade would soon be on the move again, pushing to the edge of the forest overlooking Materborn.

The German resistance stiffened as reinforcements were fed into their lines. Further south of the 160th Brigade, The East Lancashires of the 158th Brigade came under fierce attack and managed to throw back the enemy with help from eight tanks of the 147th Regiment Royal Armoured Corps which had managed to struggle through the nearly impassable tracks.

Good progress was also made by the 44th Brigade of the 15th Scottish Division which prepared to breach the Siegfried Line in their sector in the early morning. Mines exploded as Flails cleared lanes through the minefields in front of the line allowing Armoured Vehicles Royal Engineers (AVREs) to lay down bridges over the anti-tank ditch. By 9 a.m. the bridging was complete and the 6th King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) riding in armored personnel carriers called Kangaroos and tanks from the Grenadier Guards smashed through the Siegfried Line. Sergeant-Major John Walls of the 6th KOSB strung up a token line of wash on the defenses in a nod to the popular tune his comrades had been humming all day, “We’re going to hang up the washing on the Siegfried Line.”

The 44th Brigade soon cleaned up the surrounding area including the village of Nutterden bagging another couple hundred prisoners and some self-propelled guns. The brigade was soon ordered to push on for Materborn before the enemy reached it. With only half an hour to spare, the 6th KOSB riding in Kangaroos reached the Bresserberg Ridge a mile from the Materborn village and near the outskirts of Cleve. There they encountered troops from the German 7th Parachute Division intending to seize the ridge. The 6th KOSB threw back the paras, but the German still blocked the road from Materborn to Cleve.

On the evening of February 9, Horrocks received news that the 44th Brigade had taken the Materborn Feature and were pushing toward Cleve. “This was the information for which I had been eagerly waiting,” Horrocks later wrote. “Speed in capturing Cleve before the German reserves got there was essential. So I unleashed my first reserve, 43rd Wessex Division, which was to pass through the 15th Scottish, to burst into the plain beyond and advance towards Goch.”

Unfortunately, the news Horrocks received was not accurate as the Germans still stubbornly resisted outside of Cleve. As a result, on February 10 a good part of the 43rdWessex and the 15th Scottish were snarled in a massive traffic jam which took most of the day to get the tanks and vehicles untangled. Horrocks candidly admitted later it “was one of the worst mistakes I made in the war.”

While much of the 43rd Wessex was stalled, its leading brigade, the 129th, pushed on following a muddy secondary road for Cleve. By dawn on the 10th the brigade swarmed into Cleve recalled Major Victor Beckhurst of the 4th Somerset Light Infantry, “thinking it had been cleared, but instead we had wandered slap-bang into the middle of a German position.” A wild firefight raged through the day as they were attacked by 16th Regiment, 6th Parachute Division, elements of the 84th Infantry and a handful of tanks and self-propelled guns. Pinned down in the rubble-strewn city, the 129th Brigade held out until relieved the next day by elements of the 15th Scottish. Cleve was finally in Allied hands.

The 9th Brigade of the 3rd Canadian Division on Horrocks’ left flank, meanwhile, riding in Buffalos broke through the partially submerged Siegfried Line capturing enemy held “island” villages. With these villages in Canadian hands the Germans would not have an escape route over the flooded area from Cleve to the Rhine River. The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders (Glens) were given the tough task of clearing the fortified village of Rindern.

“We got in there all right,” remembered Lieutenant Colonel Roger Rowley, the Glen’s commander, “but they were waiting for us.” Brutal house-to-house fighting raged as the Glens took the village and beat back counterattacks by enemy paratroopers. By the 11th, Rindern was firmly under Canadian control. Over the next day the 9th Brigade secured a couple more villages in their flooded zone.

While the 30th Corps continued its muddy advance, Lieutenant General Simpson of the American 9th Army could only fume as the Roer River rose. Before Operation Grenade was to be launched on February 10 two dams had to be captured which controlled the river’s water levels. A couple of divisions from the U.S. 1st Army were given the task. Before they could capture the Schwammenauel Dam the Germans had disabled the discharge valves on the dam allowing a strong flow of water into the Roer River valley. By doing this the Germans had created a longer lasting flood then had they just blown the dam. Operation Grenade was now postponed until the Roer River’s water level dropped.

With Cleve lost, it was now clear to the German high command that the 1st Canadian Army’s attack was the major Allied thrust into the Rhineland. Reinforcements were quickly being dispatched to help the beleaguered 84th Infantry. Gen. Eugen Meindl’s 2nd Parachute Corps was sent to the Goch area. The 6th Parachute Division, which the 129th Brigade had encountered in Cleve, and the 180th Infantry Division were arriving on the front as well to help stall the British and Canadians. The 47th Panzer Corps was being shifted away from the flooding Roer River front toward Cleve.

South of Cleve in the Reichswald, the 53rd Welsh Division continued their grueling forest battle. By February 11 the 160th and 158th Brigades had reached the eastern fringe of the forest and then swung southward. The Germans grudgingly fell back from one position to another. At times their self-propelled guns blazed away down the narrow tracks, slowing the mud-caked Welshmen. The push continued south the next day, now with the 43rdWessex also driving southward from Cleve on the outside of Reichswald. Both divisions repulsed fierce counterattacks by 15th PanzerGrenadier Division and 116th Panzer Division of the 47th Panzer Corps. Two days later on the 14th, Reichswald was cleared of the enemy except for small pockets that had to be mopped up. Two days later the Welsh troops were pushing south of the forest meeting tough resistance as they advanced toward Goch.

To the west, the 51st Highland Division had taken Gennep on the 10th, where the 1st Gordon Highlanders had to root out the Germans in deadly street fighting. Pushing toward Hekkens which was strongly fortified as part of the Siegfried Line, the Highlanders met strong resistance on February 11. That afternoon the 5th Seaforth Highlanders attack on the village was stopped cold by machine gun fire. The Highlanders took cover in a shallow ditch and were pinned down for most of the day until the arrival of tanks helped them withdraw.

Artillery soon opened up on Hekkens. The 154th Brigade attacked with its two Black Watch battalions closing following the severe bombardment. As the barrage lifted the Highlanders surged into Hekkens as bewildered Germans were stumbling out of their bomb shelters. About 300 German soldiers were quickly captured and Hekkens was in the hands of the 51st Division.

The 30th Corps continued their advance for Goch, a key point in the German defenses. Attempting to block them was the Panzer 47th Corps holding an improvised line stretching from the Moyland Wood to the Cleve Forest. Here this line met another defensive line anchored on the Cleve-Goch road.

Taking advantage of clear skies on February 14 thousands of sorties were made by Allied air support not only on the battlefront, but also deeper into Germany. That day the 46th Brigade, 15th Scottish Division attacked Moyland Wood which consisted of a three-mile-long forest and high ground. The forest was plagued with boobytraps, mines, barbed wire and machine gun posts positioned to provide murderous interlocking fire. The troops of the 46th Brigade endured heavy fire as they moved through the mud toward the forest.

Wicked enemy machine gun fire stalled the 46th Brigade attacks the next day. Adding to their misery was mortar and artillery shells crashed among them. “We fought as we’d never fought before,” remembered Lieutenant A.W. Waddell of the 9 Cameronians of the bitter fighting as the German fought desperately to hold the line.

On February 15, the 43rd Brigade was now under the command of the 3rd Canadian Division which took over the 15th Scottish Division’s front. The bulk of this division would soon be passing through the 43rdWessex Division taking part in the attack on Goch. The 2nd Canadian Corps under Lt. Gen. Guy Simonds was now on the left flank of the 30th Corps. The 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions now returned to his command, and the latter division soon took over the fighting for Moyland Wood.

Elsewhere, the 43rd Wessex Division had broken through the German defenses east and south of the Cleve Forest. The 214th Brigade with supporting tanks set off on the evening of the 16th clearing villages of enemy troops as they headed toward Goch. By early the next morning they had reached the escarpment overlooking the key town and the Niers River that flowed through it. Goch was critical to the Germans with its rail line and three key roads passing through it. As part of the Siegfried Line one anti-tank ditch encircled the town on three sides, while a second one circled all of Goch. Concrete and steel pill boxes and emplacements further strengthened the German defenses as did a number minefields.

Meanwhile, fighting for the Moyland Wood continued as the 7th Brigade of the 3rd Canadian Division, supported by tanks from Scots Guards, entered the bloody area on the afternoon of the 16th. Fighting would rage in the Moyland Wood for the next five days. Tracked carriers called “Wasps,” armed with flamethrowers, helped the Canucks slowly shove back the stubborn enemy fighting to defend the Fatherland. Elements of the German 6th Parachute Division were fed in the battle and they launched vicious counterattacks against the Canadians.

Finally, on February 21, while rocket firing Typhoons provided air support, The Royal Winnipeg Rifles with tanks from the Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment and flame-spewing Wasps cleared the Germans out of the Wood. That night two sharp counterattacks were thrown back. Moyland Wood was in Canadian hands, but it had cost the 7th Brigade about 500 casualties.

While the 7th Brigade battled it out for Moyland Wood, the 4th Brigade of the 2nd Canadian Division launched an attack on a key section of the Goch-Calcar Road on February 19. This attack was to help support the advance of the 30th Corps on Goch. At midday artillery opened up as Kangaroos carrying two rifle companies of the two attacking battalions—The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (RHLI) and The Essex Scottish Regiment. These units were supported by tank squadrons from the Fort Garry Horse.

Mud bogged down some of the Kangaroos and Shermans—some of the latter also being disabled by mines. German 88mm guns forced the rest of the Kangaroos to stop short of their object as the infantrymen quickly cleared the carriers. Enduring vicious machine gun fire, the two battalions reached farms and buildings near the road and dug in. German counterattacks were beaten back, although more were to come.

The Panzer Lehr Division had arrived and they attacked after dark with a powerful battlegroup of infantry and tanks, supported by mortar and artillery fire. The battlegroup had broken through as far as the tactical headquarters of the RHLI, while a couple of its companies were being infiltrated by tanks and infantry. The RHLI’s commander, Lt. Col. Denis Whitaker, called in his reserve company to help restore the situation by the early morning of the 20th. Elsewhere attacking elements of the 116th Panzer Division overran the forward companies of the Essex Scottish. Resisting fiercely, Lt. Col. J.E.C. Pangman, commander of the Essex Scottish, was reporting it was “touch and go” as there were “enemy tanks and infantry all about.”

The next morning the Royal Regiment of Canada and tanks from the Fort Garry Horse enduring enemy fire fought their way to the Goch-Calcar Road. After driving off enemy counterattacks, they reached the Essex Scottish headquarters and other survivors of that unit. The tanks and Royals eventually secured their position. A squadron of tanks and elements of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, meanwhile, reinforced the RHLI and helped beat back a German attack.

More German counterattacks were thrown back during the day by the battered 4th Brigade. At 6 p.m. the darkness soon lit up with the flash of tank, machine gun and small arms fire as the Panzer Lehr attacked one last time. After two hours of fighting the Germans were driven back. While Typhoons overhead attacked any that moved, sporadic fighting continued the next day, but the Germans having suffered heavy losses were done. On the night of 21/22 the Germans withdrew leaving the Goch-Calcar road to the Canadians.

To the southwest the 52nd Lowland Division of the British 2nd Corps had entered the battle now and were fighting on the 51st Highland Division’s right flank. The 51st Highland Division, meanwhile, continued their advance toward Goch, securing village after village in hard fighting. Enemy strong points were taken out under the cover of smoke by fire breathing Churchill Crocodiles and AVREs firing penetrating charges. Reaching the outskirts of Goch, they with the 15th Scottish Division were given the task of taking the key town.

On February 18 the 44th Brigade led the 15th Scottish Division’s attack on the town sector north of the Niers River. AVREs from the 79th Armoured Division had earlier under the cover of darkness laid bridges across the outer anti-tank ditch where they established seven crossings. Crossing the inner ditch proved more troublesome as the AVREs struggled to get a bridge in place. They and the accompanying 8th Royal Scots had come under machine gun fire and that of a self-propelled gun as well.

By mid-afternoon the 6th KOSB had arrived and by midnight they had established a hold on the northern part of town. Things went better the next morning when the remaining brigade’s battalion, the 6th Royal Scots, joined the other two battalions. With assistance from tanks of the 4th Grenadier Guards and flame throwing Wasps, the three battalions fought their way down to the river’s edge clearing houses.

After the 152nd Brigade of the 51st Highland had established a bridgehead over the anti-tank ditch during the night of February 18, early the next morning the 153rd Brigade fought its way into town. “The rest of the day was perfectly bloody,” commented Major Martin Lindsay, acting commander of the 1st Gordon Highlanders. “The street was badly cratered by debris so we could not use tanks or Crocodiles, and any sortie by the bulldozer was met by aimed small-arms fire from snipers.” Despite the 153rd Brigade’s capture of the German garrison commander, Col. Paul Matussek, bitter fighting continued to rage.

Meindl of the 2nd Parachute Corps, who had taken over the front on either side of Goch, sent in reinforcements. Bitter fighting went on for a couple of days before the town was secured by the 30th Corps. The Germans withdrew.

The two-week battle for the Reichswald and breaking through the Siegfried Line in that sector was over. The British and Canadians had suffered about 8,500 killed and wounded, while the Germans had over 11,700 captured and an equal number killed or wounded. The fighting, however, was far from over.

On February 23 the U.S. 9th Army crossed the receding Roer River as they launched Operation Grenade. Three days later the 2nd Canadian Corps supported by 30th Corps launched Operation Blockbuster which would see hard fighting in clearing the Hochwald Layback. On March 10 the last German troops withdrew across the Rhine River ending the muddy, bloody battle for the Rhineland. Horrocks would later write, “I was very glad to have it behind me.” He was likely not the only one to think that.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments