By Pedro Garcia

As the Civil War continued in the spring of 1864, a Shenandoah Valley resident lamented, “Our prospects look gloomy, very gloomy.” Those prospects dimmed even further when the relentless new Union general in chief, Ulysses S. Grant, orchestrated a concerted scheme of simultaneous advances. “My primary mission,” Grant declared, “is to bring pressure to bear on the Confederacy so no longer [can] it take advantage of interior lines.” Grant focused on the key Southern cities of Atlanta and Richmond. While Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman drove into Georgia, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks would advance into Louisiana and southern Arkansas. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade would lead the Army of the Potomac against its old nemesis, Robert E. Lee, in Virginia.

In support of the drive on Richmond, Grant called for a move from western Virginia into the Shenandoah Valley to divert attention from Meade’s effort, tying down much-needed Confederate troops. One of the richest and most productive regions in the South, the Shenandoah, called “the Breadbasket of the Confederacy,” is cradled between the Allegheny and Blue Ridge Mountains. Approximately 125 miles long, the valley stretches from Martinsburg, West Virginia, to Staunton in southern Virginia. The headwaters of the Shenandoah River rise 10 miles below Staunton and flow northward to its confluence with the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry. The topography of the countryside gives rise to some odd local terminology. Because the river flowed from south to north, the northern end is referred to as the Lower Valley and the southern end as the Upper Valley. Hence, to travel north was considered going down the valley, and moving south was considered going up the valley.

Grant’s plan called for a Union column under Brig. Gen. George Crook to attack the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, one of Lee’s vital lifelines, and seize the key transportation center at Staunton. A second column, 9,000 men strong, would tear up the rail line and descend on the major Confederate supply depot at Lynchburg. In command of the second column was Maj. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord, supported—somewhat reluctantly—by Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel.

With the 1864 presidential election looming, Abraham Lincoln had specifically asked the War Department to give Sigel an important and visible command. Sigel’s influence with the burgeoning German community in St. Louis had been instrumental in electing Lincoln in 1860. The military commander’s resume was mixed, at best, at this stage of the war. His military reputation was in almost inverse proportion to his political usefulness and ability to attract recruits. “I’m going to fight mit Sigel,” German recruits would boast. When the war broke out, Sigel was commissioned a colonel in the 3rd Infantry Regiment in St. Louis. He got off to a bad start at the Battles of Carthage and Wilson’s Creek, but despite his poor showings Sigel was promoted to brigadier general, further underscoring his prominence as a political general.

Siegel redeemed himself to a degree at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in March 1862, deftly handling Union artillery. He was given another star and transferred to the eastern theater of war. He led a division and then a corps in the Shenandoah Valley, where he was part of a collective thumping at the hands of Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson at the Battle of Second Manassas. He then took command of the largely German XI Corps of the Army of the Potomac but was abruptly relieved of command in February 1863. Since then, Sigel had been exiled to a minor post in Pennsylvania.

Sigel was more or less forced on Grant. Well aware of the German’s deficiencies, Grant sought to limit his involvement without creating a political fuss. He ultimately decided to give Sigel an administrative and logistical support role, with troops in the field to be commanded by Ord. The attack on the railroad was given first priority, while Sigel’s role was largely diversionary. Grant explained Sigel’s part in the campaign to Sherman. “I don’t expect much from Sigel’s movement,” wrote Grant to his confidant. “I don’t calculate on very great results.” Quoting Lincoln, Grant continued, “If Sigel can’t skin himself, he can hold a leg while someone else does.”

In stark contrast to Sigel’s career, former U.S. Vice President John C. Breckinridge had performed admirably on the battlefield. The Kentucky native had seen his first major action at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, where he commanded a brigade of Kentucky troops, the soon to be famous “Orphan Brigade.” His actions at Shiloh earned Breckinridge a promotion to major general and the respect of his men and fellow officers. As a hard and desperate fighter, he had few, if any, superiors in either army. In early March, he was given command of all Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley and asked to cover a vast geographical department that stretched from West Virginia to southwestern Virginia and parts of Tennessee and Kentucky. “I trust you will drive the enemy back,” Lee wrote to Breckinridge. To do so, the former vice president had less than 5,000 troops at his disposal.

Ord, by contrast, was to have more than 9,500 men in his command, including 8,000 infantry provided by Sigel. But Sigel bridled at his support role and in the end sent Ord only 6,500 men. When Ord asked him to bring up supplies, Sigel responded, in effect, “I don’t think I shall do it.” Ord soon tired of Sigel’s foot dragging and resigned his command on April 17, which was probably what Sigel was angling for in the first place. The German happily took over the column, moving south from Martinsburg on April 29. His infantry, divided into two brigades, was led by Brig. Gen. Jeremiah Sullivan, while Sigel’s chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel, had charge of the cavalry.

General John Imboden Takes Up the Confederate Defense

As word of Sigel’s advance reached Richmond, Breckinridge took steps to checkmate the Union move into the valley. The man charged with the defense was Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden. A native of Staunton, Imboden had intimate knowledge of his domain. He had served as a captain of artillery under Stonewall Jackson in 1861 and later recruited and raised a cavalry battalion. His most notable achievement came at Gettysburg, where he successfully covered the Confederate retreat and secured, against daunting odds, the army’s vital crossing point over a rain-swollen Potomac River at Williamsport. Shortly afterward, Imboden was named district commander in the valley, with 1,500 troopers under his control, including the 18th, 23rd, and 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry, as well as a battery of artillery. They were tasked with observing, harassing, and slowing down Sigel’s advance, buying time for Breckinridge to assemble his forces.

Imboden sent two companies of the 23rd Virginia Cavalry, under Major Fielding Calmese, to operate on the road between Romney and Winchester. Union scouts detected the activity, and portions of the 6th and 7th West Virginia Cavalry, as well as 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, rode out in pursuit. The blue-clad horsemen tirelessly gave chase but failed to come to grips with the Confederates. No sooner had the Federals called off the pursuit than fresh Confederate cavalry appeared on the scene. “In a little while,” wrote a resident of Winchester, “the Yankees came back and went down the Martinsburg road.” In a few moments, they were followed by Calmese, leading his men triumphantly through the streets.

When the news of the running victory reached Breckinridge and Lee, it was viewed as a favorable portent of things to come. A soldier in the 51st Virginia wrote home, “My opinion is that right here in this country will be the next fighting in the spring.” He was right. Before the month was out, Imboden was calling for local companies of reserves and militia to bolster his ranks. Rockingham and Augusta Counties, in the central part of the valley, contributed six companies of reservists made up of boys too young and men too old to join the army.

Imboden also reached out to Francis Smith, superintendent of the Virginia Military Institute at Lexington, raising the possibility that the youthful cadets might be pressed into service. When the war began, the cadets had gone to Richmond to act as drillmasters for the thousands of raw recruits joining the army. In May 1862, they had marched with Jackson to the Battle of McDowell but did not see action there. Now, two years later, they were itching to get into the fight. The feeling was best summed up by a 19-year-old cadet who wrote his mother: “I think you had just as well give your consent at once to my resigning and entering the Army. I want to have some of the glory of the year ‘64 attached to my name.” Smith offered the cadets to Robert E. Lee, but Lee expressed the droll hope that the boys would remain in school, thus avoiding the necessity of what President Jefferson Davis had termed “grinding the seed corn of the nation.”

Sigel, satisfied that he had completed his preliminary assignment, moved his headquarters from Cumberland to Martinsburg and made final preparations for the trip southward up the valley. Two days later, Sigel’s force entered Winchester and immediately abandoned any further idea of advance. Despite continued evidence of the enemy’s weakness, Sigel lost any sense of urgency, preferring to maintain a rigid routine of drill, inspection, and review—even staging mock battles to gauge how his troops would behave under fire. According to an officer in the 116th Ohio, such pointless posturing “bred in everyone the most supreme contempt for General Sigel. Not an officer or man retained a spark of respect for, or confidence in, him.”

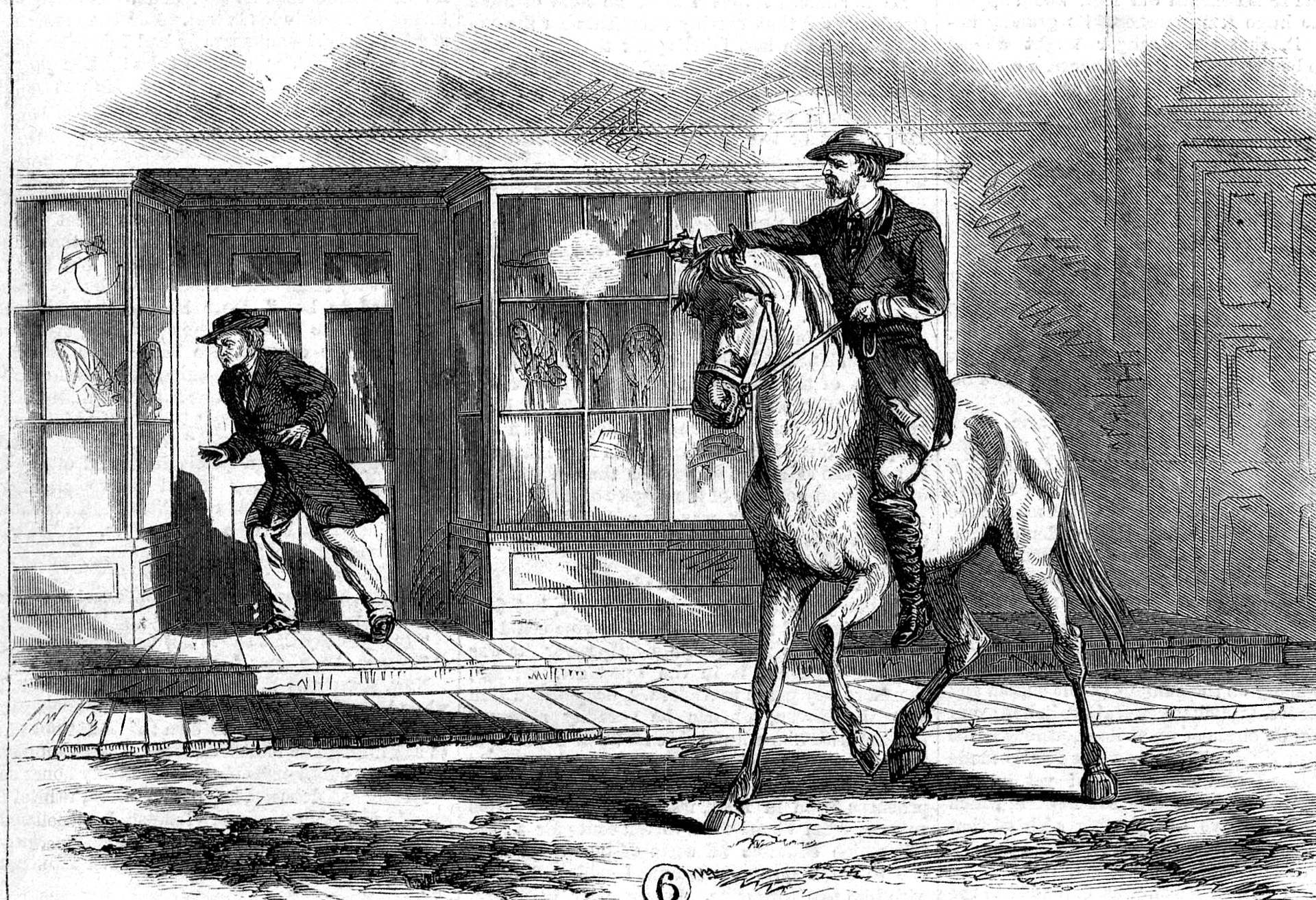

Sigel’s sloth-like advance was exacerbated by the need to detach large numbers of troops to deal with the threat posed by Confederate partisan raiders John Mosby and John “Hanse” McNeill, who were terrorizing Sigel’s lines of supply and communication. Despite the incessant raiding and mounted clashes, Sigel’s main body advanced to Woodstock on May 11. A sharp skirmish there drove the Confederate defenders from the town in such haste that they left behind several unsent telegrams written by Breckinridge and intended for Imboden. These communications revealed that several thousand Confederates were at that very moment coming to his assistance but that Breckinridge was still uncertain about Sigel’s destination or purpose.

Having stumbled upon this invaluable intelligence, Sigel could not be spurred to action. Instead, he dispatched Colonel William Boyd and 300 troopers of the 1st New York Cavalry on a scouting mission to secure Sigel’s left flank. Boyd soon ran into another Confederate trap at New Market Gap. The Southern troopers had inflicted two severe reverses on Federal forces in one week, and Sigel’s cavalry would go into the coming battle seriously weakened.

Meanwhile, on the morning of May 13, some 40 miles away in Staunton, Breckinridge announced that he was “determined not to await Sigel’s coming, but to march to meet him and give him battle wherever found.” The Kentuckian had arrived in town eight days earlier, mustering all the militia in the area, and on May 10 he had summoned the 264-man Corps of Cadets from the Virginia Military Institute, fresh from raising a commemorative flag at the gravesite of Stonewall Jackson, who had died exactly one year earlier. Breckinridge asked the cadets to stand by to help repel the Union invasion. Meanwhile, he was joined by the veteran brigades of Brig. Gens. John Echols and Gabriel Wharton, totaling another 2,500 men. Including Imboden’s men, Breckinridge now mustered 4,816 men at arms.

As the Confederate column snaked through Harrisonburg on May 14, the low rumble of artillery and distant gunfire announced the arrival of Sigel’s advance guard at New Market. Colonel Augustus Moor, commander of the 1st Brigade, was ordered to conduct a reconnaissance in force to probe Imboden’s position and seize the small crossroads village if possible. Moor did so, driving the thin gray line of defenders four miles southwest of town onto a commanding eminence called Shirley’s Hill.

The day’s running skirmish settled into a brief but furious artillery duel. Fitful fighting continued throughout the night. “It had been raining all day and continued all night, a cold rain that soaked us to the skin,” remembered a soldier in the 123rd Ohio. “We remained in line all night, sleeping but little on the cold, muddy ground. It was one of the most uncomfortable nights I ever spent.” As darkness fell, Moor’s brigade of roughly 2,300 men, fully one-third of the army, dug in northwest of town on a slightly lower rise called Manor’s Hill.

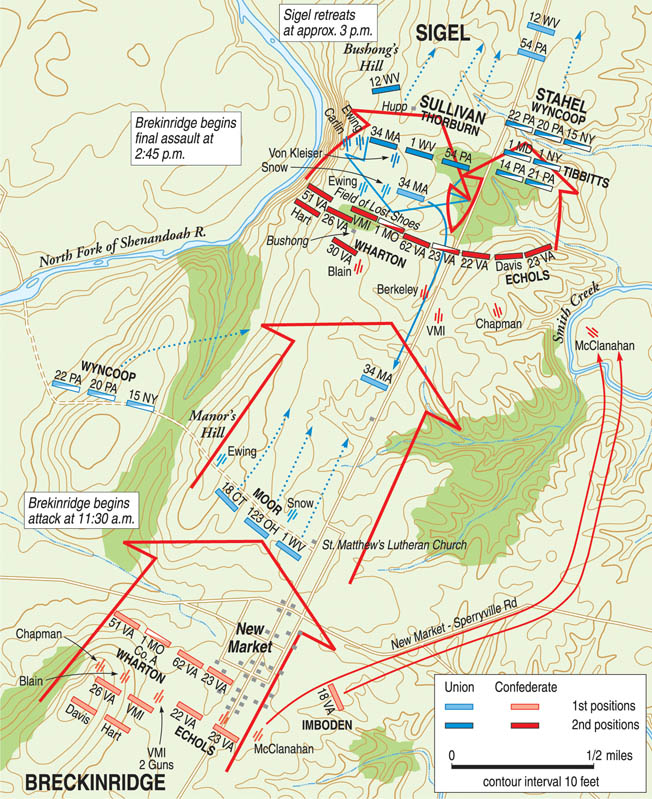

A Narrow Front at New Market

The battlefield at New Market was a box-like peninsula defined by Shirley’s Hill on the south, Bushong’s Hill on the north, the Shenandoah River on the west, and Smith’s Creek to the east. The terrain would force the Federals to fight on a narrow front, and the rains flooded the local streams, rendering them impassable. It was on the far western point of the constricted land corridor at Bushong’s Hill that Sigel’s army would deploy for battle, but as Sunday, May 15, dawned, he was still 20 miles away at Woodstock.

Sunrise gave a clear view of the field, and Breckinridge studied it carefully with his binoculars. Satisfied that the enemy had no immediate offensive intentions, the Kentuckian declared: “We can attack and whip him here. I’ll do it.” Artillery began barking back and forth as Breckinridge made his final dispositions on the northern slope of Shirley’s Hill, out of Federal view. It would be an assault in depth, with Wharton’s brigade on the left, Echols’s brigade on the right, and the 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry holding the center. The VMI cadets, whose spruce uniforms had drawn catcalls of “Katydids!” and “Rock-a-bye Baby!” from the amused veterans, formed in reserve, constituting Breckinridge’s last line.

Just before the Confederate infantry stepped off, Breckinridge spurred his horse up to the young cadets. “Young gentlemen,” he said, “I hope there will be no occasion to use you, but if there is, I trust you will do your duty.” Commandant Lt. Col. Scott Shipp ordered the Corps’ white battle flag unfurled while the band struck up a jaunty tune as the cadets moved into place down Shirley’s Hill. Shipp, at 24, was scarcely older than the cadets he commanded, whose average age was 17. The cadets were armed with Austrian rifles and 40 rounds of ammunition in their cartridge boxes. Two 3-inch rifled cannons from the school’s artillery section rattled along behind them.

Shipp had not been briefed by the veteran generals to rush his cadets down the hill, and they moved at a leisurely rate, as though they were still on the parade ground. Suddenly, a Federal shell exploded in the midst of Companies C and D. The war had suddenly become all too real. Captain Govan Hill, an adult tactical officer in Company C, dropped with a fractured skull. Private Charles E. Read was struck over the right eye by a shell fragment, and James L. Merritt was hit in the abdomen by a piece of shrapnel that knocked him down but did not penetrate the skin. Pierre Woodlief of Company B also fell. Beside them, 17-year-old cadet John S. Wise was also hit. He remembered the shell vividly: “It burst directly in my face: lightning leaped, fire flashed, the earth rocked, the sky whirled around and I feel upon my knees. Cadet Sergeant [William] Cabell looked at me pityingly and called out, ‘Close up, men!’ as he passed. I knew no more.” Finally, the rest of the corps reached the safety of the valley below.

Withdrawal From New Market

On a field lashed by heavy rains, a double line of skirmishers from the 30th Virginia Battalion surged forward at 11 am. A Federal soldier conceded later that he and his comrades had been taken by surprise. “We were not looking for trouble,” he said, being “in ignorance of the fact of the proximity of Breckinridge’s forces.” As it was, Imboden struck first, sending the 18th and 23rd Virginia charging through the woods on the right and flushing out the blue-clad pickets. The gray line moved resolutely over the crest, down Shirley’s Hill and through town, cheered on by citizens. One resident remembered, “The little town, which a moment before had seemed to sleep so peacefully that Sabbath morn, was now wreathed in battle smoke and swarming with troops hurrying to their positions.”

When fully fleshed out, Breckinridge’s extended line of battle stretched well beyond the flanks of Moor’s defensive position at Manor’s Hill, making his line instantly untenable. A soldier in the 18th Connecticut wrote, “As soon as the Confederate support came in sight we were ordered to fall back.” Another bluejacket from the 123rd Ohio recalled that the Confederates came “sweeping like an avalanche.” From atop Manor’s Hill, Major Theodore Lang fired off five messages to Sigel, urging him to come up quickly. Reinforcements dribbled in throughout the morning from the strung-out Federal column, and as they arrived they were met by wounded and stragglers moving in the opposite direction. “As we went up there was evidence of a heavy fight going on in front,” grumbled one disgusted artilleryman. “The road was lined with stragglers who kept shouting to us to give it to them, and then getting to the rear as fast as they could.”

Sigel arrived on the field about noon and almost immediately demonstrated his lack of appreciation for the true conditions at the front, rebuking Lang for being unnecessarily excited about the fate of the army. With the Confederate juggernaut in full view, driving everything before them, Lang asked Sigel about the whereabouts of the rest of the army. When Sigel nonchalantly replied that they were coming, Lang countered with a searing “Yes, General, but too late.” Sigel ordered Moor to evacuate his position slowly and fall back to a new one. Moor disengaged skillfully and withdrew several hundred yards, reforming on a ridgeline known as Rice’s Hill. In the process, he was compelled to give up the town of New Market.

At this point in the battle, Breckinridge stopped the advance, pausing to redress ranks, shift positions, and adapt his plans to the fluid circumstances. The halt consumed less than an hour, and the Confederates advanced again at 2 pm. Moor recalled that he was “hardly in line when the rebels heralded their advance by their peculiar yell.” The onrushing Confederate wave swept forward with considerable momentum, and the second Federal position of the day dissolved into a chaotic withdrawal. However, Moor’s short struggle had bought Sigel time to form a new line atop Bushong’s Hill. It ran for nearly a mile and included the 54th Pennsylvania, 34th Massachusetts, and 1st and 12th West Virginia Regiments. As the Confederates approached Sigel’s main line, one of Breckinridge’s staff officers noted, “It was evident that the enemy had determined to make his final stand.”

Supporting the new Union line were four batteries that began working with trip-hammer rapidity and fearful precision. The Confederates continued to advance swiftly and steadily in the face of galling fire. A Federal artillerist observed: “On they came without wavering, and closing up the gaps that four batteries were cutting through them, and yelling like demons. The order is passed for two-second fuses. The next moment there is a demand along the line for canister, the men work with a will, and we pour the canister among them and for about ten minutes we pour canister from twelve guns right into them.” An officer in the 34th Massachusetts had a similar recollection: “We waited until they were close enough, and then rose up and gave it to them. They halted and kept up a hot fire. Three times their colors fell and were raised.”

The Confederate left-center faltered and collapsed. Within the space of a few minutes, the 62nd Virginia lost nearly half its strength, the right-half of the 51st Virginia was caved in, and the 1st Missouri and 30th Virginia were also badly broken up. The VMI cadets, following in reserve, again took casualties. Privates Henry Jones and Charles Crockett of Company D were killed instantly by an exploding shell.

With the Confederates reeling, there was an opportunity for a well-placed and well-led counterattack. “Just here a cavalry charge would have won the day for the Yankees,” conceded a wounded officer of the 30th Virginia. However, rather than striking a blow where the enemy had just been driven back in confusion, Sigel launched his weakened cavalry against the enemy right, where Echols’s brigade had yet to be engaged and where Breckinridge had placed 10 cannons and ordered the guns to be double-shotted with canister. An aide to the general reported, “It had scarcely been done before they were seen advancing in squadron front, when, coming in range, the artillery opened.”

Among the massed artillery were two guns from VMI. “We got quickly into action with canister against cavalry charging down the road and adjacent fields. When the smoke cleared away the cavalry seemed to have been completely broken up,” recalled Lieutenant Collier Minge. A Federal sergeant noted succinctly, “They mowed us down like grass.” About this time, Sigel’s infantry was preparing its own counterattack aimed at the weakened Confederate center. The result was a series of disjointed, badly coordinated lunges at the enemy. “We were receiving fire not only from our front, but from our left, and almost our rear. In fact, we were nearly surrounded,” lamented an officer in the 34th Massachusetts.

To make matters worse, there was no cavalry support on the Union left, having been decimated in the earlier attempt to break the Confederate right. “The enemy pressed forward his right, which extended some distance beyond our left, and was rapidly flanking me in that direction,” reported Colonel Jason Campbell of the 54th Pennsylvania. Anxiously watching the attack unfold, a Federal gunner observed, “Our infantry forms for the charge; they move forward, with the glorious old flag to the front. I felt that the day was ours, for their line was already giving ground. But alas, they do not go more than a hundred yards till they waver and fall back, and we now felt it would be a desperate struggle for the battery, for every man knew we were whipped.”

“Put the Boys In”

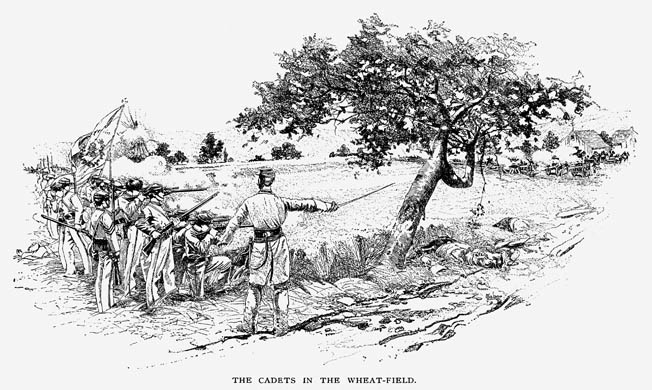

An ugly gap opened in the Confederate center, directly in front of Breckinridge’s only available reserves—the 26th Virginia Battalion and the VMI cadets. An aide, Major Charles Semple, suggested putting the cadets into line. Breckinridge resisted briefly, then conceded the inevitable. “Put the boys in,” he said, “and may God forgive me for the order.” The cadets swept forward with a wild yell, heading into the orchard below Bushong’s Hill. “The fire was withering,” recalled Commandant Shipp. “It seemed impossible than any living creature could escape.” Private Beverly “Jack” Stanard fell mortally wounded with a shattered leg; his comrade, Private Thomas G. Jefferson, was fatally shot in the stomach. Shipp was struck in the left shoulder by a spent shell fragment and turned over command to senior tactical officer Henry A. Wise. One cadet remembered a regular officer’s attempt to rally his shattered command: “I shall never forget his language—‘Rally men and go to the front. Here you are running to the rear like a lot of frightened sheep. Look at those children going to the front. Rally and follow those children!’”

Union Major Lang conceded, “I never witnessed a more gallant advance and final charge than was given by those brave boys on that field. They fought like veterans, nor did the dropping of their comrades by the ruthless bullets deter them from their mission.” Cadet Wise remembered the moment forever. “The order was given to the cadets to advance upon the enemy, and they moved promptly and most spiritedly,” he said, “driving the enemy in their immediate front from the field, capturing guns and prisoners.” With the initiative in their favor, Breckinridge’s men swept forward again, driving the deflated Federals from the field in utter confusion. An officer in the 12th West Virginia recalled, “It seemed the very gates of pandemonium had opened up.”

Sigel mounted a belated counterattack, but the Confederates drove off Stahel’s cavalry and smashed in a frontal assault by the 34th Massachusetts, 1st West Virginia, and 54th Pennsylvania. The Massachusetts troops suffered the most, losing half their number in a matter of moments; even their canine mascots were cut down in the charge. The VMI cadets swarmed over the 30th New York Artillery, driving it from the field and capturing a gun. Color bearer O.P. Evans straddled the cannon and exultantly waved the Corps’ white battle flag.

The pursuit continued for several miles to the Shenandoah River, where Sigel’s rear guard burned the bridge across the swollen stream at Mount Jackson. By the time the sound of gunfire died away at 7 pm, almost 1,400 men were casualties. Federal losses totaled 762; the Confederates lost about 600. The toll was especially large among the VMI cadets. Five were dead on the battlefield: William Cabell, Charles Crockett, Henry Jones, William McDowell, and Jack Stanard. Five others—Samuel Atwill, Luther Haynes, Thomas G. Jefferson, Joseph Wheelwright, and Alva Hartsfield—would die later of their wounds. Another 47 cadets were wounded—nearly one-fourth of the entire number who took part in the battle.

Ulysses S. Grant, stymied by his own troubles at Spotsylvania, bombarded General-in-Chief Henry Halleck in Washington. “Cannot General Sigel go up to Shenandoah Valley to Staunton?” he wired. Halleck immediately wired back that Sigel, far from advancing, was “already in full retreat. If you expect anything from him you will be mistaken. He will do nothing but run. He never did anything else.” A furious Grant relieved the German of command on May 21.

The Battle of New Market saved the Shenandoah Valley for the Confederacy for the time being. More than that, it immediately entered into myth. The churned up wheat field across which the VMI cadets charged became immortalized as “the Field of Lost Shoes,” since many of the boy-soldiers’ shoes were sucked from their feet by the knee-deep mud. Each year on the anniversary of the battle, the entire Cadet Corps musters in while the names of the dead at New Market are read off in turn. As the names are called, a representative of their company steps forward and reports simply: “Dead on the field of honor, Sir.”

Originally Published in Military Heritage magazine.

My Son is a VMI Graduate. I have seen the annual ceremony and its inspiring what they did.

I’ve been there for the ceremony and it is a moving tribute to what the cadets achieved.

A prime example of the courage and gallantry that Southerners were (and still are) famous for.