By Kevin M. Hymel

Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr., looked forward to fighting German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, his North African nemesis. But it would not be Rommel who faced Patton on the battlefields of Tunisia in the spring of 1943.

Patton had started the war in Morocco with Operation Torch on November 8, 1942. As the commander of the Western Task Force, he had landed a force on the beaches on French Morocco and, after three days of fighting, accepted the surrender of the Vichy French. While Patton attended to administrative duties in Casablanca, the war continued in Algeria and Tunisia. It was there that German forces under General Jurgen von Arnim smashed into the American II Corps under Major General Lloyd Fredendall at Sidi Bou Zid on February 14, 1943. Rommel followed up von Arnim’s attack two days later, driving the Americans back some 50 miles to Kasserine Pass. At least 300 Americans had been killed, 3,000 wounded, and nearly 3,000 were missing in action, not to mention the tons of lost equipment. The attack had badly shaken American confidence.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the overall Allied commander in North Africa, needed a new commander to take over II Corps. After offering the job to generals Ernest Harmon and Mark Clark, both of whom turned it down, Eisenhower sent for Patton, who arrived on March 5. Eisenhower simply explained II Corps’ mission: help to squeeze the Germans between the British Eighth Army, approaching from the south, and the British First Army, attacking from the west. Patton’s two objectives were to tie up as many German units as possible until British General Bernard Law Montgomery’s Eighth Army pushed through Rommel’s Mareth Line, and to capture the port town of Gafsa, which Montgomery could then use as a supply base.

The famous Field Marshal Rommel had departed North Africa on March 9, eight days before Patton attacked the German line. He had been promoted to commander of Army Group Africa, but the new position was merely a charade. In the previous weeks and months, he had clashed with his superiors and his Italian allies, his negative assessments of the situation having displeased Hitler. In addition, Rommel’s heart, nerves, and rheumatism were dragging him down. That morning he boarded a plane and flew to Rome to assume his new command.

General von Arnim took command of all forces in Tunisia, now called Army Group Afrika. Rommel or no, there was still a German army fighting in North Africa. Neither Patton nor any of the Allies realized Rommel had left for good, and all of them believed that they were still fighting the Desert Fox. Nevertheless, Patton appreciated his new task. “I suppose it is an honor to be given all the tough nuts to crack,” he boasted to his wife Beatrice. “I hope my teeth hold out.”

With Montgomery’s offensive stalled at Rommel’s Mareth Line, Patton hoped his offensive in western Tunisia would draw off German reserves, creating a weakened force for Montgomery to overwhelm and continue his northern drive. If things went well, Patton might even drive to Gabès, splitting the enemy in two in the process.

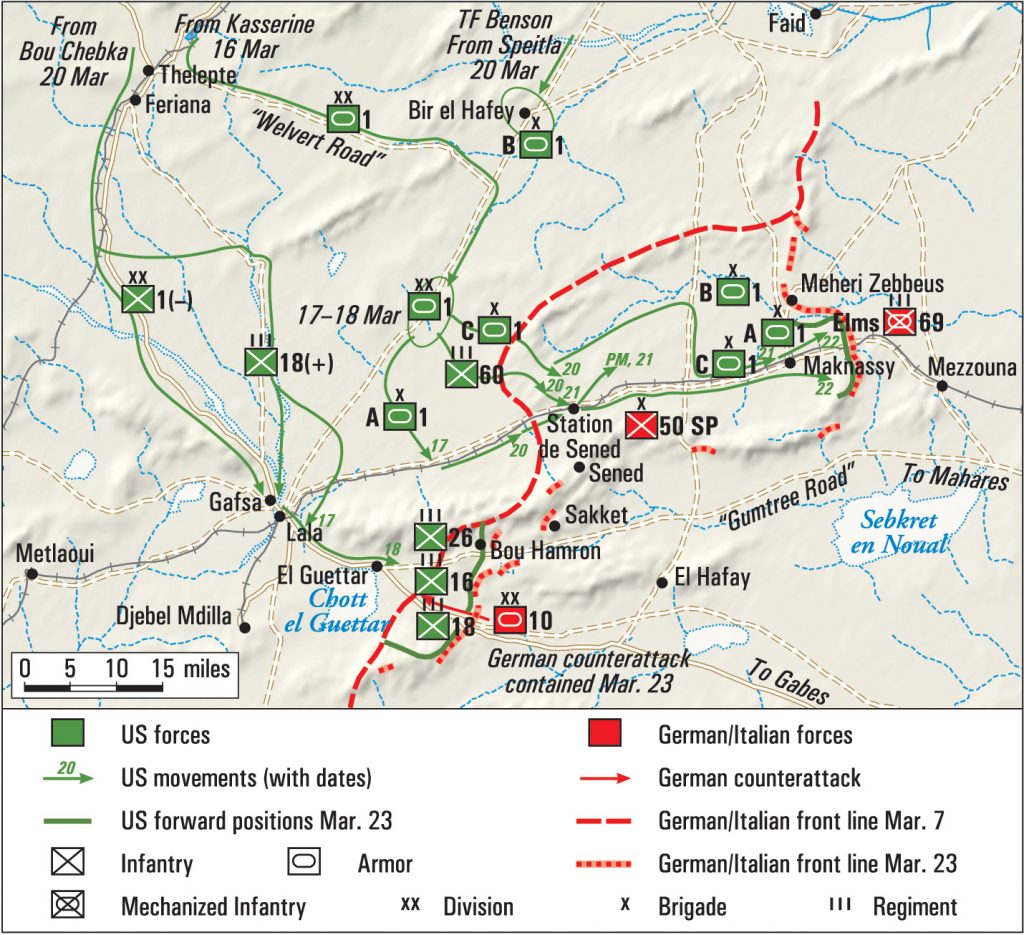

For the offensive, Patton planned to send Major General Terry Allen’s 1st Infantry Division south from Feriana to attack and hold Gafsa, some 45 miles away. Once completed, Major General Orlando Ward’s 1st Armored Division, supported by elements of Major General Manton Eddy’s 9th Infantry Division, would head out of Kasserine Pass and attack southeast past Gafsa, driving some 25 miles east to Maknassy. Defending the passes to Patton’s rear would be other elements of the 9th, as well as Major General Charles Ryder’s 34th Infantry Division.

It was a simple plan, but Patton knew there was nothing simple about combat. The day before he got II Corps rolling, he assessed his divisions. Of the four, he considered only Allen’s 1st Infantry ready for battle, Ward’s 1st Armored too “timid,” and Ryder’s 34th Infantry too defensive-minded. He reserved judgment about Eddy’s 9th Infantry, which had yet to experience any real fighting, still blessed with, in Patton’s words, the “valor of ignorance.” Patton considered Eddy, a World War I veteran, an excellent tactician but too cautious.

Patton wanted to start forward on March 15, but heavy rains forced him to delay until March 17. He fancied a whimsical idea to control the moving parts of the offensive: he wished he were triplets so he could command the two attacking divisions and the corps himself. He visited Allen on March 16 to make final preparations before the offensive. Allen’s troops would be up against the Italian Centauro Division, which defended Gafsa, but Patton worried that the German 21st Panzer Division might join the fight.

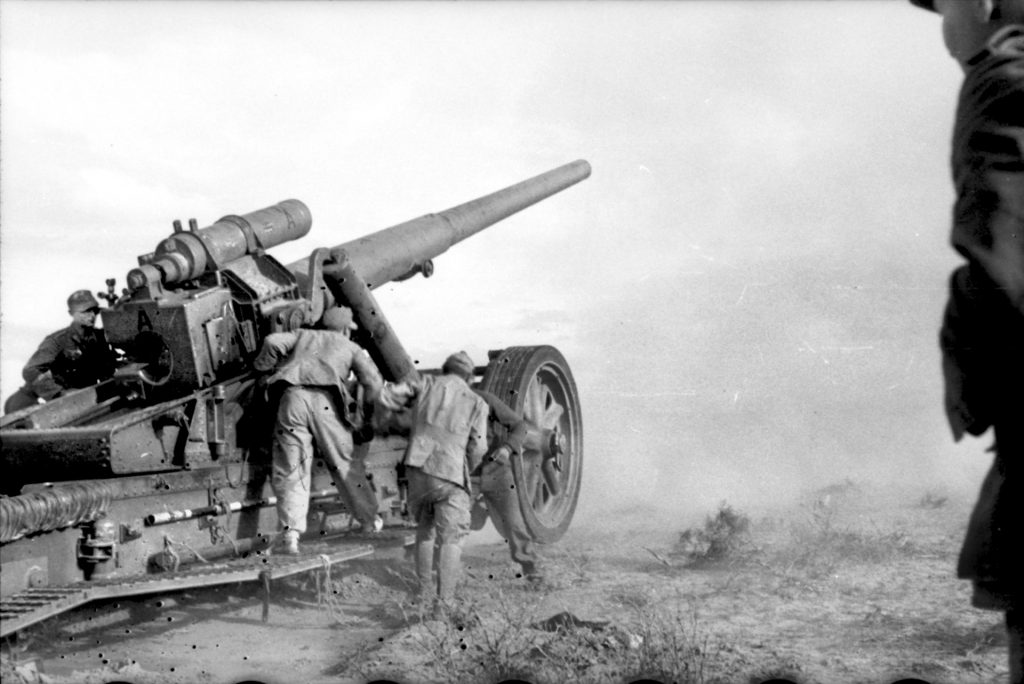

When Patton noticed that one of Allen’s infantry regiments lacked anti-tank support, he ordered Allen to remedy the situation. Allen tapped the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion, composed of 34 lightly-armored M3 half-tracks armed mostly with 37mm guns, with a few 75mm guns, as opposed to thicker-armored M10 tank destroyers, which ran on a tank chassis and sported a 76.2mm gun. It proved an important decision.

Later that day, Patton addressed his staff. “Gentleman, tomorrow we attack. If we are not victorious, let no one come back alive.” Then he retired to his bedroom to pray. That evening, as the troops of II Corps moved to their assembly areas, Patton hosted Eisenhower and British General Harold Alexander, the commander of 18th Army Group, and their staffs at his Feriana headquarters for what he dubbed Operation WOP, a politically incorrect name, since the Americans were facing Italian troops. Tension hung in the air as the commanders worried that the Germans might strike first, before II Corps made its move. Alexander paced back and forth in front of Patton’s fireplace, still concerned about the Americans’ fighting prowess. “We might get in trouble,” he stressed, if II Corps found itself in a pitched, indecisive battle.

At the designated hour, the troops started forward. Whenever Patton received a battlefield update, he would whisper it to Eisenhower, who listened intently with his hands behind his back, and then Alexander, who continued to pace. A large map on the wall depicted Allied and enemy positions, but the generals ignored it. Outside, soldiers shoveled sand through a window to set up a sand table map. Patton later wrote that he “radiated confidence,” despite one genuine worry. “The only trouble I have is a cold-sore on my lip.” That night, as Patton prepared for bed, he received reports that there was fighting north of Gafsa. “Well,” he wrote, “the battle is on.”

As the sun rose on March 17, Patton went out to observe the 1st Infantry Division enter Gasfa. When he saw no movement on the battlefield, he stormed up to Allen and asked, “What the hell is this? When are you going to move?” Allen surprised him with, “General, we are already on our first objective,” adding that he had not been given permission to make a night attack. In fact, he had been told expressly not to launch a night attack.

When Allen tried to explain his actions by mentioning Knute Rockne, the renowned Notre Dame football coach from the 1920s who popularized the forward pass, Patton asked, “What the hell does a Swede football coach have to do with night attacks?” Allen answered, “Why beat your brains out for a yard and a half when you can throw for 40 yards?” Allen’s attack had been a forward pass for the infantry. Patton now knew he had a creative, aggressive commander in charge of the 1st Infantry Division.

Later in the day, Patton drove to the front, where he climbed a large rock outside Gafsa and uneasily surveyed the town, not convinced it was yet in American hands. He watched as artillery shells burst in the distance and American troops advanced. “Go down that track until you get blown up,” he told his aide, Dick Jenson, “then come back and report.” Jenson took off in his jeep with a bevy of curious reporters following. The town was deserted; the Italian Centauro Division, which had been defending the city, had pulled out, and the 21st Panzer Division never showed itself. It was a bloodless victory.

Patton climbed into the back of his command car. As he neared Gafsa, he ordered his driver to stop next to a reporter-filled jeep. He smiled, pointed at his command car and, wanting to defend his warrior image, explained, “I’m using that because the tank I usually move around in hasn’t caught up with me yet.” Then he looked through his binoculars at some soldiers walking up a hill toward the town. He handed the binoculars to a reporter. “That’s the 16th Infantry [Regiment] going up that hill ahead. Looks as though they’re going right into Gafsa.”

When a reporter asked him how the battle was going, Patton told him, “Oh, fine, fine. But I’d feel happier if I knew where the Germans were. As long as I know where they are, I don’t mind how hard they fight. But I’d like to know where they are.” With that, he climbed back into his vehicle and sped into the city. That night, in a letter to his wife, Patton admitted his feelings about the advance. “When I started forward, I was really scared of an air attack but soon got used to it and stopped worrying.”

Patton had won his first victory as II Corps commander. More important, his attack had forced von Arnim to commit two-thirds of his mobile reserve to his western front on the eve of Montgomery’s offensive. Both Eisenhower and Alexander visited Patton to tell him they were pleased with his progress, albeit against nothing. Eisenhower later informed Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, “The officers and men of both divisions are in fine shape and eager to fight. Patton, assisted by Bradley, has done a splendid job in a very short time.” Eisenhower was right; II Corps had come a long way since the Kasserine Pass debacle.

Despite Patton’s success, he chaffed at remaining in his headquarters during a battle, even if it was the right thing to do. “When one is fighting Erwin [Rommel] one has to be near the radio.” But his advance was about to slow. For the next two days it rained incessantly, bogging down everything in a sea of mud. Alexander ordered Patton to halt while Montgomery pressed north. Patton had little choice. He still worried that Rommel would hit II Corps before he could continue his attack or before Montgomery assaulted the enemy’s Mareth Line, scheduled for the next day. “I feel that if I strike first Erwin will have to parry.”

Patton hated to pause and give the enemy time to regroup. With nothing else to do, he checked on the 1st Armored Division, visiting Brigadier General Paul Robinette, commanding Ward’s Combat Command A. An English-speaking German prisoner was with Robinette when Patton found him. “The poor son-of-a-bitch must be up to some trickery,” Patton told him.

Once Robinette updated him on the situation, Patton began laying scorn on the Germans, finally exploding with, “We will kick the bastards out of Africa!” As Patton left, Robinette told him it was an honor to have the corps commander visit. Patton slapped him on the back, saying, “By God, it will not be the last time you see me.” Yet, Patton’s mood changed when he wrote in his diary that night about Robinette: “He is defensive and lacks confidence.” Patton next visited General Ward, who complained that his tanks could not advance in the rainy conditions. Patton told him to use his armored infantry and move their weapons in half-tracks.

Patton returned to his headquarters to find Alexander, who explained II Corps’ follow-up objectives, telling him his 9th Infantry Division would be transferred to the British. Worse, as Montgomery pushed up from the south, Patton was to stay at Gafsa and Maknassy and let Montgomery pass in front of him, leaving the American forces out for the rest of the campaign and negating Patton’s scheme to drive the Germans to the sea. “I kept my temper and agreed,” Patton recorded in his diary. “I hope I will be back in Morocco on another job before we get pinched out.”

The next day, Patton’s aide Captain Jenson wrote Mrs. Patton, updating her on her husband’s well-being. His recent promotion to lieutenant general and new command had changed him, Jenson reported. “He is years younger in feeling and appearance … If he gets any more good news, we will have to sit on him to keep him down.” But Patton was far from happy. His fear of seeing II Corps left behind while Montgomery pursued the Germans even made it into the II Corps Operation Report. “This plan apparently envisaged pinching out the II Corps after the capture of FONDOUK heights.” Patton sent Bradley to Alexander to argue against the plan.

Alexander’s staff told Bradley that the slight was not intentional, just that their logisticians calculated that II Corps could not be resupplied over the existing roads. Bradley then visited Eisenhower, who had no idea of Alexander’s plans. Bradley recommended moving II Corps north to attack Bizerte, the last key city of the campaign. Eisenhower studied Bradley’s recommendation on a map, then called Alexander, telling him he wanted to keep II Corps in the fight. He followed it up with a letter insisting that the unit should remain on the line “right up the bitter end of the campaign.” Patton’s plan worked; II Corps would remain on the battlefield with all of its units intact.

Meanwhile, Patton continued pushing east. On March 21, Ward’s 1st Armored Division captured Sened Station, the halfway mark between Gafsa and Maknassy, while Allen’s 1st Infantry Division pushed east from Gafsa. The forces they attacked were mostly Italian infantry supported by German reconnaissance and artillery. Patton visited Allen at a company command post set up in a farmhouse. There, the two generals, accompanied by a captain, watched a heavy artillery barrage, followed by Allen’s infantrymen maneuvering deftly over rocky terrain and punching into the Italians.

After watching several hundred prisoners pour through the American lines (one of his aides called them “additional Roman ruins”), Patton, Allen, and the captain walked forward until they found a hill to perch on and watch the action close-up. Suddenly, a salvo of enemy artillery screeched in. The captain, Allen, and Patton all jumped into a foxhole on top of each other. “It’s too damn hot,” said Patton. “Lets’ get the hell out of here.” As Patton left, he noticed an enemy barrage explode right where he had been sitting.

Things were not going as well for the 1st Armored Division. Patton visited Sened Station, where he determined Ward was moving too slowly—a sin for the branch that was supposed to slash into the enemy. He ordered Ward to drive harder and move his command post closer to the action. When that did not work, he sent General Hugh Gaffey to prod him, again without result.

When Ward mentioned in a phone call to Patton that he had the good fortune of not losing any officers that day, Patton exploded. “Goddammit Ward, that’s not fortunate. That’s bad for the morale of the enlisted men. I want you to get more officers killed.” When a stunned Ward asked Patton if he was serious, Patton shot back, “Yes, Goddammit, I’m serious. I want you to put some officers out as observers well up front and keep them there until a couple get killed.”

The next day, March 22, Patton received word that the Germans and Italians were slugging it out with Montgomery along the Mareth Line. Obviously, he was not drawing enough enemy troops away from Montgomery. Alexander now wanted Patton to make an armored thrust through Maknassy and head for the sea between Sfax and Gabès. But Ward called to say he had captured Maknassy but failed to assault the enemy-occupied heights east of the town.

While Ward’s lack of aggressiveness angered Patton, he blamed himself. “If I had led First Armored Division we would have taken the heights.” Patton ordered Ward to capture the heights immediately, since intelligence reported the German 10th Panzer Division was heading toward him. Ward obeyed the order but failed in the mission.

A furious Patton then called Allen to check on the 1st Infantry Division’s progress. When Allen’s intelligence officer told him they had not yet captured a hill named Djebel Berda to their right, Patton exploded, “Well goddamn it, get moving, and get there right away!” and hung up the phone. It took Allen’s men most of the day to capture the objective, but they got it done.

Patton braced for the attack on Ward. He went to bed that night fully clothed, ready to jump into action, but the attack on Maknassy never materialized. Instead, the 10th Panzer Division smashed into Allen’s 1st Infantry Division at El Guettar. Allen reported the attack to Patton at 6:30 am, and Patton immediately pushed infantry, artillery, and tank-destroyer battalions to him.

Allen ordered the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion, the unit he picked after Patton told him to bolster his anti-tank capability, forward to defend his artillery units. The lightly armored halftracks slugged it out with the German tanks until what was left of them were forced to pull back. The Germans cut through one regiment, captured two artillery batteries, and penetrated to within two miles of Allen’s headquarters, but in the process they lost a host of tanks and infantry.

Allied air forces took more than an hour to reach the battlefield, but once they did they flew 340 sorties, hitting the German supply lines. The Germans attacked again five hours later, but this time the Americans intercepted the attack order, and the men of the Big Red One were ready. While the Americans sacrificed many of their anti-tank guns, trading space for time, the Germans sent in their infantry in front of their tanks, only to be cut down by American artillery airbursts. The Germans suffered more than 300 casualties. Allen’s men knocked out 37 enemy tanks, with much of the tank killing done by the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion.

Patton worried about his lack of artillery pieces and shells. When two artillery battalions ran out of ammunition, the Germans overran them. An opportunity to smash a German tank unit had been lost when another U.S. artillery unit ran low and had to conserve ammunition. Patton rushed the 7th Field Artillery Battalion, then supporting the 1st Armored Division, to the battlefield. It arrived in the nick of time to turn back the Germans’ morning assault. According to Brigadier General Clift Andrus, the 1st Infantry Division’s artillery commander who witnessed the 7th in action, its rounds hammered into the German unit until “the battalion broke from cover and started to run for another wadi in the rear. But none ever reached it.”

As for ammunition, Brigadier General Reese Howell, the artillery commander for the 9th Infantry, trucked shells to the front from Tebessa, some 65 miles away, despite a lack of air cover. The shells, like the 7th Field Artillery, reached the front in the nick of time. Months after the campaign ended, Patton told Andrus, “You know, Andrus, you really made a God-damned horse’s ass out of me? But you also taught me something.” Patton then explained he had almost lost El Guettar because of his artillery ammunition shortage. Andrus explained about Howell’s actions, and Patton, ever the student of war, had Andrus write up a report on artillery resupply ideas. According to Andrus, “We always had ammunition after that.”

Patton spent part of the battle watching from an observation post. As the enemy lines thinned and wavered under American artillery and anti-tank fire, he shook his head. “They’re murdering good infantry,” he said to no one in particular. “What a helluva way to expend good infantry troops.” He only called Allen once during the battle. When Allen complained about the lack of air support, Patton changed the subject and wondered, “I don’t understand the loss of so many tank destroyers,” not appreciating how vulnerable half-tracks were to tank fire. When Allen explained their contribution to the battle, Patton merely hung up.

Patton got one break from the tension. When he saw a soldier sporting a green beret walking down the street outside his headquarters, he asked Lieutenant Colonel William O. Darby, the head of the 1st Ranger Battalion, “What the hell is that?” Darby explained he was a British chaplain assigned to the Rangers “and about the only man I know who can get away with not wearing a helmet.” Patton laughed uncontrollably at the situation.

Patton and Allen’s fighting spirit filtered down to the soldiers in the trenches. A half-written letter by one of Allen’s soldiers, penned during a lull in the battle, opened, “Well folks, we stopped the best they had.” But El Guettar was a defensive battle, not the slashing, flanking pursuit of victory Patton sought. In other words, it was no Second Manassas. Patton had spent the battle working the phones from his corps headquarters, just like Eisenhower had ordered. That night, before going to bed, he penned in his diary, “I hate fighting from the rear.”

While the Germans were unable to capture Djebel Berda, the hill Patton personally told Allen to capture, they did cut off the regiment defending it and kept their distance so the Americans could not knock out their tanks. When it was over, however, Allen’s troops had held their ground and the Germans had retreated. It marked the first clear American victory against the Nazi war machine.

The next day, March 24, Patton visited the battlefield. On the way, his column passed a group of 1st Infantry Division soldiers, one of whom was not wearing leggings. Patton stopped his vehicle and ordered the man to put them on, despite the man’s nasty leg sore. As he approached Allen’s headquarters, a German shell exploded nearby, pelting his vehicle with metal shards. The Germans had retreated but were still firing at the Americans.

The shelling continued as Patton climbed a rocky hill to Allen’s command post, using a silver-tipped cane to keep his balance. At the top, he dropped into a foxhole to discuss the situation with Allen and Brigadier General Teddy Roosevelt, Jr., namesake of his father, the 26th president and Allen’s deputy commander, who explained the various phases of the battle. When Patton learned that Allen’s men had sent a message to the Germans daring them to attack, he asked Allen, “When are you going to take this damned war seriously?”

Patton took in the battlefield’s devastation: crippled enemy tanks, ruined American tank destroyers, and the corpses of the German infantrymen cut down by artillery fire. The tank-destroyer losses disappointed Patton. Only 10 of the 34 howitzer-armed M-3 half-tracks survived, while four of the 12 M-10 tank destroyers survived. Instead of exercising cover and concealment, the various tank- destroyer crews maneuvered, exposing their inferior armor protection and guaranteeing their destruction. The crews had little choice as they rushed to engage the enemy tanks. Although the Germans had lost 31 tanks, they managed to retrieve 16 of them that night. Their bravery in tank removal impressed Patton.

Patton took in the battlefield’s devastation: crippled enemy tanks, ruined American tank destroyers, and the corpses of the German infantrymen cut down by artillery fire. The tank-destroyer losses disappointed Patton. Only 10 of the 34 howitzer-armed M-3 half-tracks survived, while four of the 12 M-10 tank destroyers survived. Instead of exercising cover and concealment, the various tank- destroyer crews maneuvered, exposing their inferior armor protection and guaranteeing their destruction. The crews had little choice as they rushed to engage the enemy tanks. Although the Germans had lost 31 tanks, they managed to retrieve 16 of them that night. Their bravery in tank removal impressed Patton.

An enemy artillery round exploded nearby and everyone ducked. When Patton spied another soldier without leggings far below the hill, he dispatched a runner to order the soldier to put them on. His conference over, Patton climbed out of the foxhole and started down the hill amid the shelling. As he passed a private, the soldier told him, “Pretty heavy artillery barrage they’re putting up.” Patton answered, “That’s not a real barrage. That’s just some German gunners ranging their guns.” Unimpressed, the private snapped back, “Well General, all I can say is if those Germans are just ranging, they are certainly ranging like hell.” The two men laughed.

A group of soldiers brought in an Arab and a donkey. In the donkey’s saddlebags were German Teller mines, which the man had planned to plant behind the Americans. Patton asked why the GIs hadn’t just “buried” him. When the men explained that he was still alive, Patton replied, “Obviously, you can’t bury him while he is alive, now do what I told you.” Patton later called the Arabs “dirty bastards” to his wife Beatrice. The incident made him look forward to Sicily, where everyone would be considered the enemy.

While Patton oversaw the El Guettar battle, it was really Allen’s victory. Patton gave Allen everything he could spare, but it was Allen who expertly positioned his men and weapons on the battlefield and fought aggressively. When the Germans closed in on his headquarters and a staff officer suggested Allen withdraw, he snapped back, “I will like hell pull out, and I’ll shoot the first bastard that does.” Patton considered Allen a fighter and gave him enough of a free hand to exchange blows with the enemy.

Patton never faced his nemesis, Rommel, but he had defeated the Germans in battle and restored faith in the American soldier that he could face the enemy and best him on the battlefield. Patton had turned the II Corps around, and, in the process, American fortunes in North Africa. One of Allen’s officers later commented that after Patton took command of II Corps, “We knew he was there to win even if he had us killed doing it.”

Frequent contributor Kevin M. Hymel is a contract historian for the U.S. Army. This article is an adaption from Mr. Hymel’s latest book, Patton’s War: An American General’s Combat Leadership, Volume 1: November 1942 – July 1944, published by University of Missouri Press. He also leads tours of Patton’s European battlefields for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours.