By Patrick J. Chaisson

“Lieutenant Rochester, take a look at this.”

The American patrol halted next to an abandoned industrial building. There, clear in the new fallen snow, they saw fresh footprints leading inside. Left by hobnail boots, these tracks could only have been made by German soldiers.

Rushing in, the GIs surprised three sentries calmly eating their lunch. It was over in a minute. The prisoners, all suffering from trench foot, were disarmed and rushed back to headquarters for interrogation. There they revealed German plans to ring in 1945 later that night with a heavy frontal assault on the American lines.

Orders quickly flashed to all units: Get ready. Holes were dug deeper, extra grenades and ammunition crates stockpiled, artillery concentrations set. New Year’s Eve parties would have to wait.

Shortening an “Overextended Front”

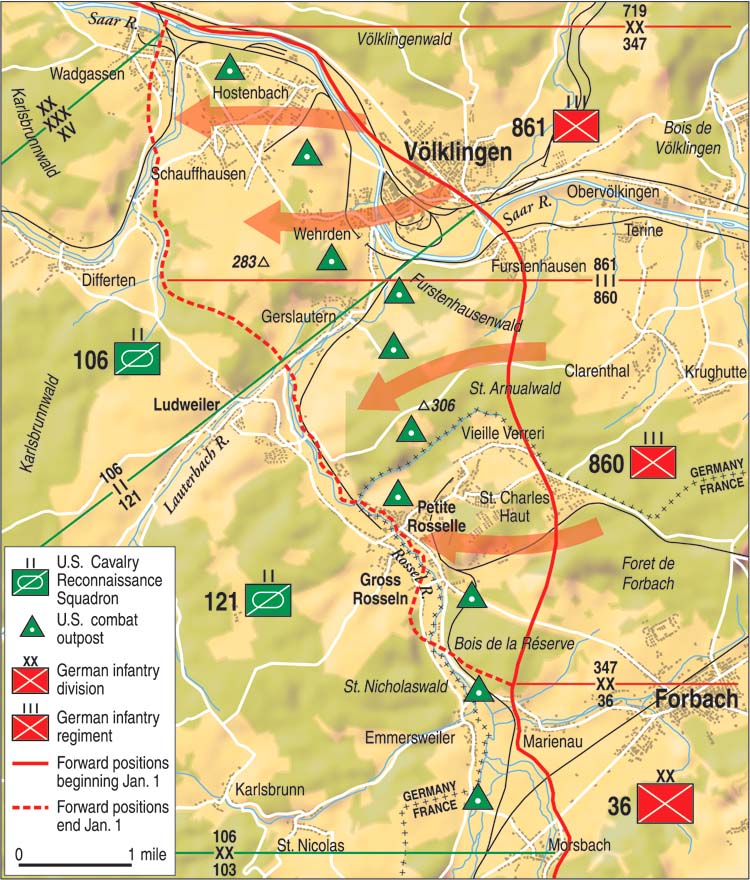

On December 31, 1944, a small force of American cavalrymen defended the hills surrounding Ludweiler, a gritty iron-making village in the Alsace region of southwestern Germany. They were stretched dangerously thin. A mere 1,500 lightly equipped troopers held an outpost line extending seven miles, normally a full division’s frontage. Intelligence officers estimated the enemy outnumbered them three to one. It appeared an impossible mission, but that was nothing new for the cavalry.

After German forces launched their massive surprise attack through Belgium’s Ardennes Forest on December 16, 1944, U.S. Third Army commander Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., staged a counteroffensive that astounded friend and foe alike with its speed, daring, and ferocity. To accomplish this, Patton disengaged two of his three corps and wheeled them north into the enemy’s exposed flank. Remaining on the line was XX Corps, which could not cover the entire Third Army sector without help.

Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower acted quickly to remedy this situation. On December 18, he directed Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers’ 6th Army Group, operating south of Patton, to cancel all attack plans and assume a defensive posture. Ike also ordered Devers to shift his northern boundary well into what was Third Army’s sector.

The 6th Army Group was badly situated for defensive operations. Allied soldiers had the rugged Vosges Mountains at their backs while facing them was a network of powerful fortifications known as the Westwall, or Siegfried Line. Commanders feared that enemy armor could punch through weakened U.S. positions and seize a chokepoint at the Saverne Gap, potentially trapping thousands of American soldiers on the Alsatian plains.

Mindful of the powerful German offensive then reaching its crescendo in the Ardennes, Eisenhower summoned Devers to his Paris headquarters on December 26 for a conference. Concerned over what he termed 6th Army Group’s “overextended front,” the supreme commander wanted all of its troops withdrawn behind the Vosges Mountains. This would shorten the lines, Ike claimed, and also make one corps available for a theater reserve.

A Delay Under Fire

Devers was loath to abandon 6th Army Group’s hard-won gains in Alsace. His principal American subordinate, Maj. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, argued that it was “a terribly difficult proposition to give up a strong defensive position when you feel confident that you can hold it.” Patch, commanding the Seventh U.S. Army, persuaded his chief to ignore for the time being Eisenhower’s orders to retreat.

Patch was taking a calculated risk by so exposing his forces, especially Maj. Gen. Wade H. Haislip’s XV Corps in the north. There the Saar River Valley made an ideal avenue of advance for any German counterattack striking toward the Saverne Gap. Adding to Haislip’s cares was an order making XV Corps responsible for covering 25 miles of front previously held by Third Army to its north.

This was a quiet sector, but XV Corps did not possess the troop strength needed to properly defend it. Haislip spread his infantry divisions out as much as he dared, yet a seven-mile gap remained on his left (northern) flank. The situation called for an “economy of force” operation, in which highly mobile troops hold a series of outposts while observing enemy activity and slowing down any assault as much as possible. Tacticians term it a delay mission, one in which outnumbered defenders trade space for time until a counterattack can be organized.

The tactical delay is a job historically assigned to cavalrymen, and Maj. Gen. Haislip fortunately had in XV Corps a battle tested cavalry outfit ready to take on this challenging mission. The 106th Cavalry Group (Mechanized) had been rolling across France, first with Third Army and now Seventh Army, since July 1944. But the 106th Cavalry’s combat experience thus far had been as the vanguard of an attacking force; this would be their first attempt at conducting a delay under fire.

The 106th Cavalry Regiment

Like many National Guard outfits, the Illinois-based 106th Cavalry Regiment was called to federal duty in 1940. The unit then was primarily horse mounted. Soon, however, wartime reorganizations required the 106th to exchange its beloved steeds for mechanized fighting vehicles more suitable for the form of rapid maneuver warfare that American forces expected to conduct.

In 1943, Colonel Vennard Wilson took command of the 106th Cavalry Regiment. A career Army officer and veteran of World War I, Wilson brought with him a strong emphasis on battle-focused training. Troopers soon adopted his no nonsense attitude, quickly learning the deadly business of mechanized reconnaissance while stationed at Camp Hood, Texas.

Soon after deploying to England in 1944, Wilson’s regiment was redesignated the 106th Cavalry Group (Mechanized). This meant its First and Second Cavalry Squadrons (each equivalent to a battalion) were deactivated and replaced by two independent cavalry reconnaissance squadrons. These units were labeled the 106th and 121st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadrons (Mechanized).

Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadrons

Group headquarters also controlled any number of attached units on the battlefield. Armor, tank destroyer, field artillery, and engineer assets could, depending on the mission, be “chopped” to the 106th Cavalry Group for a specific time and released once their work was done. These attachments assisted the 106th and 121st Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadrons in their primary duty: gaining and maintaining contact with the enemy.

A cavalry reconnaissance squadron (CRS) was uniquely configured to serve as the combat commander’s eyes and ears. Fast-moving, flexible, and heavily armed, the CRS performed a variety of battlefield tasks ranging from long-range reconnaissance and pursuit operations to more mundane chores such as route clearance and security.

The CRS operated as a combined arms formation with three reconnaissance troops (company equivalent) acting as the maneuver element, an assault gun troop providing fire support, and a light tank company bringing armored shock effect to the fight. Troops A, B, and C were designated as the squadron’s reconnaissance component, Troop E as their assault gun outfit (there was no Troop D), and Company F the tank unit. A squadron headquarters/service troop and medical detachment completed the CRS organization.

The 145-man reconnaissance troop was made up of a headquarters section and three platoons, each containing 29 cavalrymen. A recon platoon’s equipment included three M8 armored cars and six jeeps, which were called “Bantams” by the 106th troopers. Three Bantams carried side-mounted .30-caliber machine guns and were used for mounted reconnaissance work; remaining vehicles transported the troop’s 60mm mortar section.

Troop E consisted of 116 men and six assault guns. Capable of both direct (line-of-sight) and indirect fire, the M8 Howitzer Motor Carriage (HMC) mounted a 75mm cannon on a light tank chassis and took five men to crew. The 94-man light tank outfit (Company F) utilized M5A1 Stuarts, each of which had a four-man crew. Company F operated with 17 M5A1s plus a maintenance and supply section.

American Momentum Halted

American cavalrymen led the charge across France following the collapse of German defenses in Normandy. The 106th Cavalry Group took part in this pursuit, often covering 40-50 miles a day as the vanguard of Maj. Gen. Haislip’s XV Corps. The cavalry’s mobility, firepower, and superb radio communications all proved decisive during the summer and early fall of 1944.

Slowed by overextended supply lines, poor weather, and stiffening enemy resistance, the Allied offensive inevitably lost momentum as winter drew near. Assigned in October to clear the Foret de Parroy near Luneberg, France, the 106th Cavalry Group spent seven weeks fighting mainly on foot. There Colonel Wilson’s outfit learned at great cost how ill equipped it was for dismounted combat. Although trained in infantry tactics, most troopers carried short-range M1 carbines and Thompson submachine guns rather than hard-hitting M1 Garands or Browning Automatic Rifles (BARs). They had none of the special support weapons found in an infantry organization, and even at full strength a cavalry platoon was less than three-quarters the size of its infantry counterpart.

These organizational shortcomings would again plague the 106th Cavalry as it took up the long left flank of XV Corps’ line during the last days of December 1944. On December 23, following an overnight road march of 60 miles, the 106th moved in to relieve elements of Third Army’s 6th Cavalry Group. A thin trace of foxholes near Wadgassen marked Patton’s southern flank, held by riflemen of the 95th Infantry Division, XX Corps. To the right, at a French town named Morsbach, stood the 103rd Infantry Division and the rest of XV Corps.

In between stretched seven miles of frontage overlooking the Saar and Rossel Rivers. The hilly terrain was pitted by several open quarries that serviced a large ironworks in Völklingen, across the Saar. Good roads connected the hamlets of Gross Rosseln, Schauffhausen, and Werbeln to Ludweiler, a small village located at the foot of what American maps labeled Hill 283. From this height, U.S. soldiers could observe everything that went on in Völklingen and the Westwall fortifications guarding that city.

To the east another quarry-scarred prominence, Hill 306, covered the French-German border. Troopers holding this section of the line had their backs to the Rossel River with only one bridge open in case they needed to retreat. Snow, ice, and extreme cold all affected operations as frostbite and trench foot forced many cavalrymen to leave their posts in search of medical attention.

Colonel Wilson’s Delaying Tactics

Knowing his unit was too weak to hold its assigned sector with continuous fortifications, Colonel Wilson instead established a system of four-man strongpoints dug in along key terrain. Each CRS employed two reconnaissance troops augmented with tanks on the outpost line while retaining one troop in reserve. The assault guns were positioned to provide fire support as needed. Roving patrols, minefields, and wire obstacles covered the ground between outposts. A system of secondary positions, set up 400-600 yards behind the outpost line, was mapped and marked so hurriedly withdrawing troopers could find their fallback locations day or night.

Backing up the cavalry were several attached units. Two artillery battalions, the 493rd Armored Field Artillery (105mm self-propelled) and the 242nd Field Artillery (105mm towed), reached out with indirect fire all along the front. Also in support was the combat-tested 2nd Chemical Mortar Battalion, whose 36 4.2-inch tubes could deliver a heavy volume of accurate high-explosive mortar fire against short-range targets.

Protecting against armored attack were six towed 3-inch antitank guns belonging to Company A, 824th Tank Destroyer (TD) Battalion. Each cavalry squadron also received a company of combat engineers. These “jacks of all trades” helped buttress the outpost line while acting as infantry, but their real value as bridge-building experts was soon to be tried.

Like most military plans, the American scheme of maneuver was simple in concept but devilishly difficult to carry out under fire. Sentries would first detect advancing enemy forces, then force them to deploy by firing their individual and crew-served weapons. As U.S. artillery, mortars, and assault guns continued to disrupt German progress, those troopers on the outpost line were to fall back on their secondary battle positions while reserves moved up. Colonel Wilson intended to repeat this process as often as necessary, swapping terrain for time until the enemy attack ran out of steam or reinforcements from XV Corps arrived.

Warning of a Coming Offensive

Soldiers of the 106th Cavalry Group and its attached units spent the last day of 1944 on high alert while trying to keep warm in their foxholes. Across the front, observers began reporting signs of increased German activity. Cavalrymen posted on Hill 283 saw enemy infantry moving around on the far side of the Saar; artillery fire broke up those formations. Late in the day, 88mm shells destroyed an antitank cannon belonging to the 824th TD Battalion. Two gunners were killed in this action.

The mid-afternoon patrol led by Lieutenant William L. Rochester of Troop C, 106th CRS brought in valuable intelligence when it returned with the three German engineers captured at Wadgassen. These talkative prisoners described a surprise attack being planned for midnight, confirming what the troopers had been observing all day. Colonel Wilson passed this news up to XV Corps while directing his cavalrymen to make all necessary preparations for a nighttime delaying action.

The generals also knew something was coming. On that very day, Seventh Army chief Maj. Gen. Patch called a meeting of his corps commanders to warn them of an imminent assault. On the outpost line no one quite knew what the enemy was up to, only that it looked big.

Operation Nordwind

In fact, the German Army had launched what would be its last major offensive in the West. Code named Operation Nordwind (Northwind), this strategy was conceived in late December by Adolf Hitler and his Western Front commander in chief, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt. Hitler and von Rundstedt saw how much the Allies had weakened their southern armies to support Patton’s Ardennes counterattack and sought to exploit that vulnerability.

Nordwind was designed as a sequential offensive, meaning the commitment of armored exploitation forces would depend on the success of initial attacks. Those first moves were to fall on the exposed U.S. Seventh Army. German commanders expected to punch a hole in the lines, opening an avenue for follow-on panzer divisions to seize the Saverne Gap and isolate Haislip’s XV Corps.

Two Sturmgruppen, division-sized assault forces, would strike American positions in the Saar Valley, 15 miles east of the 106th Cavalry Group’s sector. The lead element consisted of crack SS infantry along with hastily trained Volksgrenadier formations, many filled with former sailors and Luftwaffe ground personnel. Orchestrating this offensive was Col. Gen. Johannes Blaskowitz, commander of Army Group G.

Operation Nordwind was set to commence at midnight on December 31, 1944. The plan also called for supporting assaults all along the U.S. lines to prevent reinforcements from rushing to the defenders’ aid. One of these thrusts was aimed squarely at the 106th Cavalry Group and its strategic hilltops.

Trierenberg’s 347th Infantry Division

On December 26, orders came down from LXXXII Army Corps to Lt. Gen. Wolf-Günther Trierenberg, commander of the 347th Infantry Division. They directed Trierenberg to conduct a limited attack on the night of December 31-January 1 with the objective of recapturing Hill 283 from the Americans. Preparations were to begin at once.

Trierenberg, a seasoned veteran of campaigns in Poland, France, and Russia, had much to do in the days before his division’s assault. The 347th was badly in need of rifles, machine guns, and, most of all, infantrymen to fire these implements of war.

Organized in 1943, the 347th Infantry Division garrisoned Amsterdam, Holland, before moving south to help stop the Allied breakout in France the next year. In September 1944, it was almost completely wiped out by the U.S. 3rd Armored Division west of Huy. Survivors retreated back to the Eifel region of western Germany, where the unit rested and reconstituted.

The German Army’s ability to rebuild itself following the fall of France is appropriately called the “Miracle in the West.” Like so many other shattered formations, Trierenberg’s division combed out all able-bodied men from its rear echelon, replacing them with amputees, the sickly, and other soldiers deemed unsuitable for frontline duty. They also received modern equipment and weapons to replace what was lost in battle.

The 347th quietly withdrew from the Eifel just prior to Hitler’s Ardennes Offensive, moving south by rail to the Saar Valley. It settled in near Völklingen, where the division continued to train replacements and acquire munitions. By the end of 1944, Lt. Gen. Trierenberg could report his artillery was nearly at full strength with one battalion (12 guns) of 150mm towed howitzers and three battalions (also 12 guns each) of 105mm cannon. These field pieces, however, were all horse drawn.

For infantry, Trierenberg had two regiments, the 860th and the 861st. Each regiment operated with two battalions, although these were down to about half their authorized manpower. The commanding general relied on the 347th Fusilier Battalion for his hardest assignments. This 300-man recon unit consisted of Trierenberg’s best-led, most heavily armed foot soldiers and was given the primary objective of taking Hill 283.

The 347th Infantry Division also possessed engineers, antitank guns, and the usual signal and support elements. While these echelons all played a role in the assault, Trierenberg’s infantry would do the heavy work. There were approximately 3,500 riflemen on hand to attempt the New Year’s Eve attack.

“We Cut Them Down Like Grass”

No artillery preparation was fired in hopes of achieving surprise. The 861st Infantry Regiment advanced on Hill 283 to the north, the 347th Fusilier Battalion making the main assault while another battalion protected its right flank along the Saar River. Farther south in the 860th Regiment’s zone, two battalions struck westward against Hill 306 and the Rossel River bridge. First contact with the Americans occurred at 2330 hours.

Sergeant Jim Moore, on the outpost line with Troop B, 106th CRS, held a strong position on top of Hill 283. Suddenly, a trip flare ignited, warning Moore of enemy activity. The unit history tells what happened next: “It was a bright, moonlit night, almost like daylight. We had our guns trained on the crest of the hill in front of us to the north. And the Germans started coming across the skyline. We cut them down like grass.”

Another member of Troop B recalled, “The enemy began firing from all sides. Our tanks and the men on the outposts returned the fire.” From his lookout in a nearby house, Private Stanley J. Szcapa “broke a window, put a machine gun through and opened fire. But in spite of all the lead, the Germans kept coming. It looked like they were drunk or doped.”

The fusiliers had completely surrounded Troop B’s widely dispersed strongpoints. One cavalryman stated his team was fighting well “but the Germans were all around us, having infiltrated to our rear before the attack.” It was time to displace.

Staff Sergeant Benjamin J. DiMichele ordered everyone out to their secondary positions. Communication wires had been cut, however, so some men failed to get the word and were taken prisoner. The rest boarded light tanks for a harrowing ride to Ludweiler.

Sergeat Hill’s Decisive Stand

Farther north, the soldiers of Troop C, 106th CRS were hit by bursts of heavy machine-gun fire just after midnight. They held against

determined assaults for 30 minutes before moving to a fallback position in the village of Schauffhausen. But the enemy got there first.

Just as they had done on Hill 283, German infantry effectively infiltrated Troop C’s lines. Prowling antitank teams destroyed two accompanying light tanks with panzerfaust rockets, prompting the troop commander, Captain John F. Brady, to pull his outfit all the way back to Ludweiler. In doing so, Brady broke Troop C’s connection to XX Corps.

The situation in the south was equally perilous. Here, the 121st CRS held a tenuous line of observation posts east of the Rossel River. Sergeant Benjamin S. Hill and his three-man team occupying Hill 306 kept careful watch as the New Year approached.

“Exactly at 2330 hours all hell broke loose,” the unit history recorded. ”It was a general bedlam of madmen shrieking and shouting, the air was filled with the clamor of personnel mines, hand grenades and shells splitting the trees. Timed between these split-second thunderclaps was the spitting fire and sharp staccato barking of a hundred burp guns.”

Some Germans threw themselves on Sergteant Hill’s wire obstacles so their comrades could step across. Others shouted for Hill and his men to give up. “Surrender, hell!” the veteran replied. “Come and get me, you sons of bitches.”

With enemy riflemen swarming all around his position, communications severed, and ammunition running low, Hill recognized it was time to go. On his order, the surviving cavalrymen boarded their vehicles and began heading back toward the bridge. Unknown to them, however, German forces had overwhelmed a platoon of engineers guarding this vital span. The only way across the Rossel was cut off.

Abandoning their trucks, Hill’s contingent took cover in the village of Petit-Rosselle. They hoped to wade the river and rejoin their unit once the enemy attack passed them by. But when a curious German infantryman discovered their hiding place, the troopers had no choice but to fight their way across.

Covering his soldiers’ escape with an M1 rifle, Hill shot seven enemy machine gunners before reaching the cover of a long trench leading to friendly territory. Hill’s cavalrymen all made it back safely, although the ordeal left everyone cold, numb, and shaken.

Colonel Wilson later termed Hill’s stubborn delay as “the decisive stand that prevented the Germans from achieving their objective of flanking the Group.” For this act Hill received the Distinguished Service Cross, America’s second highest award for valor, but did not live to receive it. He was killed in action near Sternberg, Germany, on April 8, 1945.

The Germans Dig Into Their Hills

Other members of the 121st CRS also swam the Rossel to safety. Several tankmen, however, refused to abandon their vehicles just because the bridge was in enemy hands. Fortunately for them, some combat engineers were on hand to construct a makeshift crossing out of scavenged I-beams and an old barn door. Their span proved just sturdy enough for the tankers’ 17-ton Stuarts to roll across.

The 347th Infantry Division’s nighttime assault had pushed Colonel Wilson’s outpost line back over a mile and captured both hilltop objectives. Its rapid advance also caused chaos in the 106th’s rear area, forcing both the group headquarters and its attached artillery to displace. This meant these cannons and chemical mortars were on the move just when needed most.

By dawn, however, all 4.2-inch mortars and 105mm howitzers were back in action. Working with the cavalry’s assault guns, they helped slow the Germans’ advance and bought time for troopers to occupy secondary battle positions. Additional help came from XX Corps artillery, which conducted counterbattery fire against enemy gun emplacements with its big 8-inch cannon.

The attack spent itself by mid-morning on New Year’s Day. While an artillery duel raged overhead, German riflemen frantically dug in on their newly won high ground. Those fusiliers who had previously faced combat warned their comrades that an American counterattack would not be long in coming. They were right.

The American Counterattack

Troop C of the 121st CRS launched a hasty assault on Hill 283 in late afternoon but was turned back by heavy fire. The enemy, having fought so hard to take this objective, was not going to surrender it without a fight. Colonel Wilson knew the situation demanded a heavier response come morning, but did he have the combat strength to accomplish it?

The job went to Troop A, 106th CRS. Just after noon on January 2, the cavalrymen set out on foot toward Hill 283 while U.S. howitzers pounded the objective. A platoon of tanks accompanied them. “There was no opposition until we approached the far edge of the woods,” recounted a unit historian. “Then the Germans started to throw in artillery fire. The advance stopped temporarily and the men looked for cover in foxholes and ditches and behind large trees.”

Once the cannonade ceased, officers got their soldiers up and moving again. “The men of the second and third platoons advanced with four light tanks,” remembered one trooper. “Everything looked fine at first. The tankers opened up and mowed down 10 or 15 Germans.” Then another enemy barrage hit, pinning the Americans down 25 yards short of their objective. A machine gun began firing on Troop A’s right flank, and men began to fall. When artillery fire knocked out one of their tanks, the GIs began to pull back. One cavalryman was killed and 12 wounded during this abortive attack.

Troop C of the 106th CRS enjoyed better success in the north. Late that afternoon they secured Wadgassen, reestablishing the link with Patton’s XX Corps. Also on January 2, the 103rd Infantry Division took responsibility for three miles of frontage previously watched by the 121st CRS. This enabled Wilson’s outfit to focus its attention on the key terrain surrounding Ludweiler.

A final attempt to push the enemy off Hill 283 took place at 1300 hours on January 3, when the dismounted cavalrymen of Troop B, 121st CRS stepped off to seize a road junction at the eastern edge of town. Worried that he was walking into an ambush, Lieutenant Robert J. Moore motioned his platoon into a row of houses. Just then a friendly 4.2-inch mortar round exploded outside. Fired short, it alerted German observers to Moore’s attack.

Enemy shellfire soon added to the lieutenant’s miseries. “My troopers were already taking cover,” Moore later wrote, “when I decided to exit this trap as rapidly as possible.” A torrent of heavy artillery followed his men as they ran. “Shells ricocheted off every house I passed,” he remembered. “The Germans were walking the barrage back with us and were doing too good of a job with it. These were highly trained crews with excellent spotting and control.”

Lieutenant Moore said the enemy threw an estimated 480 rounds at his platoon that day. Only one cavalryman suffered minor injuries, but a shell fragment “murdered” the treasured gas cooking stove Moore had been carrying since Normandy. He mourned the loss of his stove for weeks.

A Successful Delaying Action by Colonel Wilson

After January 4, both the Americans and Germans around Ludweiler seemed content to hold in place. Neither side possessed sufficient combat power to mount a follow-on attack, nor were the belligerents willing to abandon what terrain they did control. Farther east, the main Nordwind assaults sputtered out as well. After battering themselves against XV Corps’ main defensive lines for three days, General Blaskowitz’s troops finally suspended all offensive activity. Occasional fighting would flare up later in January, but it soon became clear that Hitler’s last offensive in the West had ended in total failure.

On the other hand, Lt. Gen. Trierenberg of the 347th Infantry Division was well satisfied with his soldiers’ performance during their New Year’s Eve assault. German riflemen took and held all assigned objectives against stiff opposition, in the process capturing key terrain, several dozen prisoners, and plenty of abandoned equipment. No record of German casualties has survived. Likely the number of killed and wounded was substantial, given the constant shelling Trierenberg’s men endured while in battle.

The 106th Cavalry Group commander could be justifiably proud of his men as well. Placed on a greatly extended line, Colonel Wilson’s lightly equipped troopers fiercely resisted an attacking force that outnumbered them at least three to one. The cavalrymen then disengaged under fire at night, a most demanding task, and occupied fallback positions from which they could not be dislodged. Their fight at Ludweiler stands as a superbly executed delaying action.

The New Year’s Eve battle cost 10 American lives with another 33 men wounded. An additional 48 GIs were reported missing in action, although most of these men later wound up in German prison camps.

For the rest of January, combat on the Ludweiler front mainly consisted of minor patrol action and occasional artillery strikes. On February 9, 1945, the 106th Cavalry Group came off the line for a well-deserved rest, its first since entering battle in July. Taking its place was the newly arrived 101st Cavalry, which recaptured Hill 283 on March 13.

Two days later the 106th Cavalry Group, refreshed and reequipped with new M24 Chaffee light tanks, joined XV Corps for its final push into the Rhineland. Once again screening the corps’ left flank, Wilson’s troopers advanced rapidly across southern Germany during 10 weeks of relentless fighting. War’s end found them in Salzburg, Austria, having ridden 1,700 miles across Europe since landing in Normandy 10 months earlier.

Their delay at Ludweiler, however, may have been the 106th’s finest hour. Maj. Gen. Haislip, the man who gave them that challenging mission, expressed his confidence in Colonel Wilson’s troopers thusly: “The 106th Cavalry Group was more than once worth a division to the XV Corps.”

Always out front, the mechanized cavalry of World War II could be counted on to take on the toughest jobs and accomplish them against great odds.

My father was in the 106 blackhorse troop in this area . He ended up in a town with a big lake in mountains where german troops learned to become sailors.John P. English i have pictures of his scout vehicle half track spent many nights in.Ialso have pictures of the 106 cavalry my dad at the eagles nest before the screaming eagles arrived.

Dan English- My uncle was a platoon sergeant in C Troop, 106th Cav. (He joined in 1940 and actually was mounted cavalry in the Black Horse Troop in Chicago). The 106th and 121st Cav ended the war in St. Wolfgang, Austria. This is the lake you referred to. I visited St. Wolfgang in 2008 because my Uncle talked about the place as such a beautiful ending to a terrible year in Europe.

Google St. Wolfgang and I’m sure photos will appear. I would post some but no way of doing so on this page. I have one of him receiving the Bronze Star and the Silver Star from Col. Venard at St. Wolfgang and another photo of him and all the C Troop Cadre sitting on a set of stairs somewhere in St. Woldgang.

Would love to see the photo of 106th c group. I believe my dad was in that group.

Did your father talk about being involved in recovering Ribbentrop gold near Salzburg?

My father was also in the B Troop of the 106th. The big town in the mountains that is mentioned above might St Wolfgang, Austria. I also have pictures from there.

Richard Lubbers We have same group photo 106 on those stairs with my dad in front of entrance. When my dad arrived at Eagles Nest after Germans fled there was just house staff everything was not disturbed dishes wine utensils all underground in concrete cellars.Your uncle must of been with my dad at camp Livingston Louisiana training with horses before they left.

My dad Ralph Jewell was in Troop B of the 106th Cav. He was one of the original Black Horse troopers from the Chicago based Illinois National Guard.

Indeed he was on maneuvers in Louisiana.

Camp livingston is another high point in dad’s time with 106 . They all arrived to new camp in Louisiana , to learn how to ride and operate with horses , but when they arrived no horses where yet their. When asked “where are the horses dad was told their coming”. Weeks later their horses arrived by rail from out west wild not saddle broke.John English had the largest horse in the 106 cavalry troop Dapper “a great spirited stead.