By Richard L. Hayes

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Americans volunteered for the U.S. armed services in unprecedented numbers. After their service, some would go on to become Hollywood and television stars, like Johnny Carson, ensign on the battleship USS Pennsylvania, patrol craft officer Kirk Douglas and Tony Curtis of the submarine Dragonette.

Some became military instructors. Hugh O’Brien became the youngest drill instructor in the Marines. Ed McMahon trained Marine Corsair pilots, Robert Stack taught naval gunnery and Robert Ryan became a judo instructor. Comedian George Gobel served his time as a B-25 instructor in Oklahoma where, as he would later claim, “Not a single Jap plane made it past Tulsa!”

Nor were the female stars relegated to only nonhazardous duty. Madeleine Carrole worked as a front-line nurse in Italy, Josephine Baker passed along French intelligence to the Allies and Carole Lombard lost her life while fund raising. Although Marlene Dietrich had renounced her German citizenship, it is unlikely that Adolf Hitler would have accepted the renunciation. Therefore, as Marlene traveled with the USO in Africa, Italy and France, she could have been shot as a traitor had she been caught behind enemy lines where she sometimes strayed.

Some stars paid a high price. Don Adams was wounded at Guadalcanal, James Arness was shot in the leg at Anzio and Art Carney was hit in Normandy. Many more were wounded. Leslie Howard (who played Ashley in Gone With the Wind) was killed by the Nazis when his airliner was deliberately shot down over the neutral waters of the Bay of Biscay.

Making it big in Hollywood has always been a gamble, and a fickle public has completely forgotten more than one actor who went too long with inadequate exposure. Those with the most to lose were the stars who had just gotten their big break, like David Niven who left Hollywood to become a commando in Europe, or Gene Kelly who had one film under his belt when he became a Navy cameraman and Sterling Hayden who fought with the OSS in Yugoslavia.

Jimmy Stewart

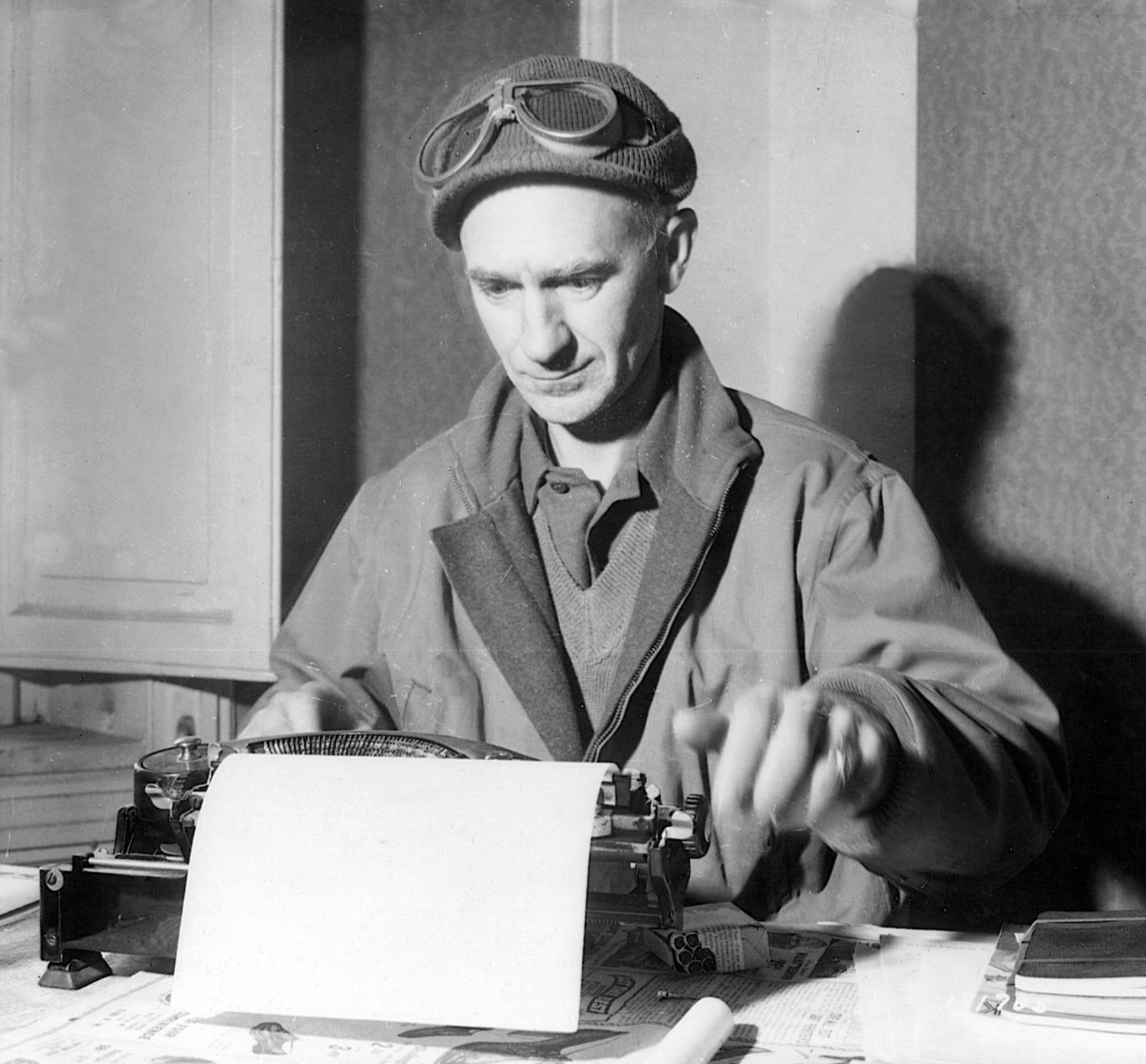

And then there were the bigger stars. Those who were well established, like Jimmy Stewart. Despite his solid movie career, evidenced by such hits as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and The Philadelphia Story (1940), Stewart was convinced early on that the war would eventually engulf the United States and got ready for it by racking up hours in his own private plane. By the time he was drafted he had plenty of flight experience and had even earned a multi-engine rating.

Stewart, however, had not prepared his body and was rejected for being too thin. Frantically, he began to eat spaghetti twice a day in an effort to gain weight. He passed his second physical—with only a half-ounce to spare— and was inducted on March 21, 1941.

At first he only flew a desk, but he resisted the Army’s effort to have him make training films and eventually ended up testing new B-17s at Moffit Field, N.M., where he also trained pilots. The job proved quite hazardous. On one training flight Stewart left the cockpit to check some instruments in the nose of the plane, leaving a young navigator with the copilot. At just that moment the No. 1 engine exploded and sent debris smashing into the cabin.

The copilot was knocked unconscious. With wind roaring into the cockpit and smoke pouring from the damaged engine, Stewart fought his way back to the flight deck and screamed at the trainee navigator to do something. But the youth just sat there, frozen with fear and shock. Stewart pulled the navigator from his seat, crawled in beside the injured copilot, hit the engine fire extinguishers, and brought the plane in on the remaining three engines.

A captain by now, Stewart was made commander of the 703rd squadron of the 445th Bomb Group in England, where he eventually flew 20 missions over occupied Europe. It was while returning from one of these missions in his B-24 named “Nine Yanks and a Jerk!” that Stewart noticed his flight leader veering 30 degrees off course and slowly pulling away from the rest of the formation.

Bombers were meant to remain in close formation, known as a “box,” using their 13 machine guns to keep Luftwaffe fighters at bay. Stragglers who fell out of the box were quickly surrounded and slaughtered, and Stewart’s leader was putting himself in just that position. Worse, this new course would take the planes over three Luftwaffe airfields.

Contacting him by radio, Stewart told the leader of his error, who replied, “No, this is the correct course, stay off the radio.” Captain Stewart then faced a difficult decision. He could disobey orders and follow the correct path with the planes in his group, or go with his wandering commander and the rest of the formation. He decided to add the firepower of his own planes to those of his errant leader, hoping that the mass of bombers would be able to fight it back to the English Channel.

No one will ever know how Stewart’s commander made such a fatal error; his plane was soon going down in flames. Other B-24s exploded in mid-air. Fighting desperately, the Academy Award winner (he had just won Best Actor for The Philadelphia Story) rocked his plane to allow his gunners better fields of fire. There were lots of targets. Over 60 Messerschmidt 109s and Focke Wulfe 190s filled the sky. More B-24s went down. But somehow every plane in Stewart’s squadron made it back. For trying to protect his commander, Jimmy Stewart was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Later, he was promoted to colonel and became Group Operations Officer of the 453rd Bomb Group, flying B-17s out of Buckinghamshire. The flyers—including a young radioman named Walter Matthau—loved to do Jimmey Stewart imitations during their colonel’s flight briefings before each mission.

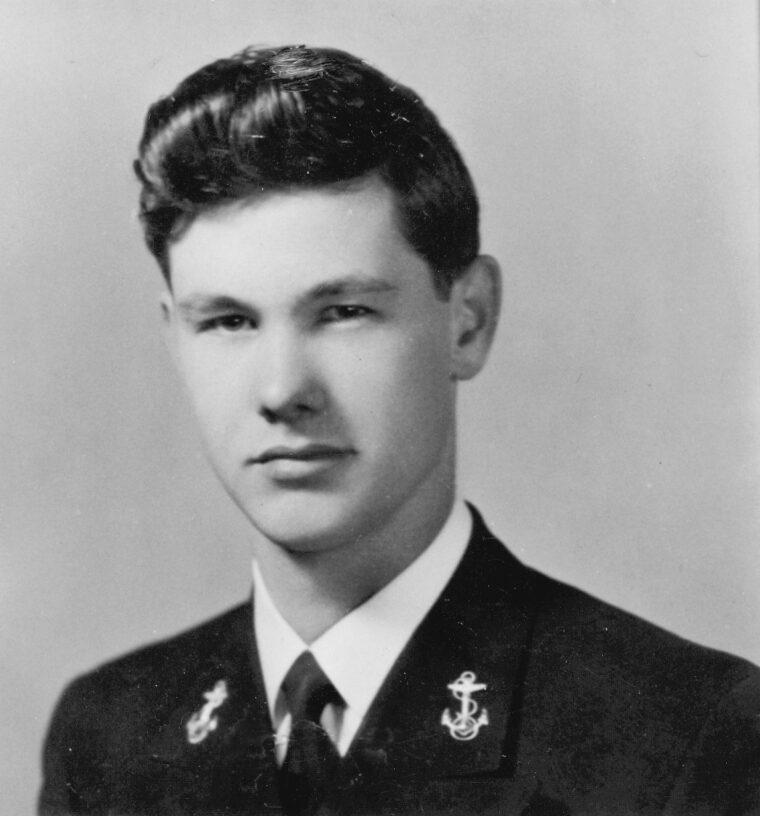

Henry Fonda

Another young actor desperate to serve was Henry Fonda. Despite his star status for such films as Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) and The Grapes of Wrath (1940), not to mention a deferment because of his two children, Jane and Peter, he enlisted in the Navy as a common seaman. And despite harassment as a “star,” he shipped out on a destroyer as quartermaster. Eventually he qualified for officers’ training and was assigned to the staff of Vice Admiral John H. Hoover on board the seaplane tender USS Curtis. Fonda aided the operations of several flying boat squadrons and even contributed to the sinking of a Japanese submarine by vectoring an aircraft to its target.

To ensure the maximum range for the planes, the Curtis usually sailed on the periphery of the fleet, a nice target for Kamikaze attacks, suicide planes loaded with bombs and explosives trying to crash into U.S. warships. One dived on the Curtis. The ship’s anti-aircraft guns killed both crewmen before they reached the ship, however, and the plane crashed harmlessly alongside in 25 feet of water.

On his own initiative, the star of The Grapes of Wrath decided to retrieve whatever maps and code books he could find from the sunken plane. Using a makeshift diving apparatus, Fonda descended to the plane, opened the canopy (which was now upside down), and fumbled among the pockets of the dead airmen as they hung from their flight harnesses.

Clark Gable

Stewart and Fonda were both rising stars, and though they were leading men, the studios did not consider their absence a major loss. Clark Gable was another story. Having just finished Gone With the Wind (1939), Gable was “King of Hollywood.”

The war had already started and Gable was finishing up another film when his wife, Carole Lombard, died in a plane crash after finishing a war-bond drive. Heartbroken, Gable threw himself into the war effort, but at 41 he had to appeal to General “Hap” Arnold himself to even enlist.Thus, he became the oldest cadet to finish officer candidate school.

It was awkward. His studio arranged to have a professional photographer drafted and assigned to the same posts as Gable to ensure an endless stream of publicity photos. Young girls threw phone numbers at him as he walked guard duty.

After graduation he was assigned to make a film about aerial gunnery. Assembling a small staff of cameramen, Gable went to England with the 351st Bomb Group. When he arrived he was welcomed on the radio by the British-born Nazi propagandist Lord Haw Haw.

The star constantly bothered his superiors with requests for combat missions. His commanding officers were reluctant. They had seen the stream of airmen returning home without arms and legs and they knew what burned men looked like. How would morale be affected back home if one of Hollywood’s major stars came home the same way?

Still, Gable begged for combat until he was finally allowed to make five B-17 flights over Europe. Some were milk runs; some were not—all were dangerous. On one mission a 20-mm anti-aircraft shell clipped off the heel of his boot, went through the plane and exited inches from Gable’s head.

But beside the flak and fighters, Gable had an added worry. When Hermann Goering got word that “Rhett Butler” was overhead, he offered a promotion, a month’s leave and $5,000 to any German pilot who could shoot him down. Knowing he would be a huge propaganda prize, Gable refused to wear a parachute.

Finally, Gable was sent home to make his motion picture about aerial gunnery. Unfortunately the film was not nearly as good as William Wyler’s Memphis Belle (1942) and it was never released.

The Army could not come up with a proper assignment for the star, so after a few months of doing nothing he was suddenly promoted to major. Disgusted, Gable quietly asked to be relieved of duty. His discharge papers were signed in Hollywood by Captain Ronald Reagan.

Sophia Loren

While Stewart and Gable flew over Europe, another movie star got quite a different view of Allied bombing, from below. Young Sophia Loren’s mother worked in a munitions factory in the small town of Pozzouli, Italy, making it a prime target for Allied bombers. There was no civil defense, and shelters were scarce. A railroad tunnel was the best protection from American bombs. After the last train to Rome rumbled through, the cavernous area would fill with people until the morning express chased them out.

Flying shrapnel caused everyone to crowd to the center of the tunnel. Not even a candle was allowed for fear the flicker would draw American planes. There was no ventilation and the place stank of sweat and excrement. Often Loren would feel the tickle of cockroaches and hear the squeal of rats as they crawled among the crowd searching for food. To this day she hates the dark.

Hoping to escape the bombs, Loren’s family moved in with relatives in Naples. There, the water mains were destroyed and Loren’s mother was reduced to draining a German truck’s radiator for drinking water.

Naples had always been known for its tough street gangs. As the Allied armies approached and German oppression increased, the gangs rose in open defiance of the German army— the so-called “Four Days of Naples.” Germans were attacked with knives, scissors, clubs, rocks or anything else Italian youths could find or steal. Often they would drop wine bottles filled with gasoline, known as Molotov cocktails, into troop trucks stalled in the narrow twisting streets.

Loren lived in a room with a balcony from where she could see the fighting. She watched as a 10-year-old boy crawled up on the deck of a German tank and threw a Molotov cocktail into the view slits. She saw the two German crewmen throw open the hatches and leap out, their uniforms and hair on fire. With pistols drawn, they chased the boy out of Loren’s sight.

When the Wehrmacht withdrew from Naples they took up positions in the hills north of town that Loren’s house happened to back up against. In front of the house was a food store. Civilians waiting in long lines for their daily rations proved too tempting for German snipers, who used them as targets. When a person in line was killed someone would drag him or her away, but no one got out of line. To lose food rations was to die anyway.

The war was very strange for the young Loren. She had never seen blond, blue-eyed people or “dresses” (kilts worn by the Scottish troops) but the strangest newcomers of all were the Americans. They gave away food! Someday the voluptuous actress would dine in the finest restaurants and star in some of the world’s most famous films, but in 1944 the most wonderful thing that ever happened to Sophia Loren was receiving a G.I.’s chocolate bar, her very first.

Audrey Hepburn

Another famous actress who would endure the war on the Continent was Audrey Hepburn. Born and raised in Arnhem, Holland, her mother assumed they would be safer there than in England, since Holland had been neutral in World War I.

As part of the intellectual elite, her family supported the Resistance and Hepburn gave clandestine ballet performances to aid the Resistance. A young teenager, she also often carried messages in her shoes. She was frequently searched at gunpoint, but never caught with incriminating evidence.

Hepburn’s uncle was shot in reprisal for the destruction of a troop train. Later, her cousin was also shot. And her beloved half-brother Ian was sent to a concentration camp, leaving Audrey and her mother to fend for themselves.

Once, in a periodic roundup for work camps, the Germans picked up Hepburn and forced her into a truck at gunpoint. There was only one guard when the truck emptied, so she dashed away and hid in an abandoned cellar. The meager lunch she had carried in her school bag soon ran out and she slipped into shock. Suffering from hunger and exposure, she stayed in the cellar, certain she would be captured and shot if she came out. Finally she stumbled home to learn that it had been three weeks since she had eaten.

In September 1944, the Dutch believed their delivery was at hand as American and British paratroopers began landing in Holland. They were part of Operation Market-Garden, combined airborne and ground offensive aimed at spanning the Rhine River at Arnhem. However, reinforcements were stalled, and, despite fierce fighting, the town remained in German hands. Most of the British paratroops who landed in Arnhem were captured. The few who escaped were aided by sympathetic townspeople, including the Hepburns, who did everything they could, and even hid six soldiers in their wardrobe while the Germans searched nearby.

Soon after the battle, the Hepburn house was bombed, and, with only the clothes on their backs, they moved in with friends. Unfortunately, German soldiers were using the top floor of their new residence as a German observation post. When the English finally captured it months later, they naturally assumed the Dutch inside were collaborators and held them at gunpoint. It was Hepburn who convinced them (in English) that they should not be punished. Liberated at last, she would later say, “Freedom smelt like English cigarettes.”

Hepburn had watched as the Jews of Arnhem were rounded up, the men separated from the women and the whole lot shipped away to concentration camps. She saw the endless streams of refugees flow by, some carrying their dead. She saw hundreds drop by the side of the road, many shot at from passing German trucks. She watched as her own friends and family were killed and their belongings stolen. To sum up her wartime experiences, the star of Sabrina (1954) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) would say, “Don’t discount anything you hear or read about the Nazis; it’s worse than you could ever imagine.”

Mel Brooks

In all wars there are sometimes elements of comedy. Mel Brooks was drafted in 1944 and assigned to the headquarters unit of the 1104th Combat Engineers ten days after the conclusion of the Battle of the Bulge when the Germans were in full retreat and throwing away equipment as they headed east.

One day Brooks and a few fellow engineers were driving around in a jeep when they spotted a case of Mauser sniper rifles lying by the side of the road. They stopped and began taking potshots with the German weapons. They soon found that the glass insulators on telephone poles made excellent targets, shattering dramatically when hit. After a while, Brooks and the others threw the rifles away and leisurely made their way back to headquarters. The place was in an uproar. Orders were being shouted. Papers were flying. Everyone was running around.

“What’s going on?” Brooks asked.

“The Germans have broken through and cut all the telephone wires!”

Thinking quickly, Brooks stepped forward.

“Sir, I volunteer to go out and fix those lines!” he shouted.

So Mel Brooks casually drove back to the same spot he and his buddies had spent the afternoon, fixed the lines that they had shot out and thus saved his entire company from the surprise German “counterattack.”

Lee Marvin

Although Lee Marvin is best remembered for his movie roles as a tough Army major (The Dirty Dozen, 1967) or a grizzled sargent (The Big Red One, 1980) he was actually a Marine. He wanted to fight so badly he dropped out of high school to enlist. He conducted 21 landings in the Marshall Islands—dirty little affairs where the Japanese positions had to be destroyed one by one.

Marvin, who was nicknamed Captain Marvel by his fellow Marines, was assigned to the lst Platoon, I Company, Third Battalion, 24th Marines, the “scout-snipers.” Usually his unit went in the night before the invasion. They debarked from fast-moving destroyers converted to troop carriers. In the early morning darkness they would slip over the side into small rubber rafts and paddle to shore where they marked out landing routes for the LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry) of the main invasion force.

On Saipan, however, Marvin and his platoon landed with the main invasion force in one of the first waves on Yellow Beach Two, just south of Challantanoa. When the Navy guns stopped, the Japanese artillery crews came out of their protected bunkers and opened up on the beach. Shells of every imaginable size rained down, Nimbu machine guns raked the landing grounds and mortars worked at close range. Marvin’s unit scrambled to the temporary protection of a long trench, only to have Japanese artillery shells land directly into their position. Realizing that going back would be suicide and going forward held the same possible result, they rushed out. Many did not make it.

It was dark by then and the Japanese counter-attacked. Flattened out in the sand, Marvin felt a bullet crash through his left boot heel. It jerked the leg back so hard he wasn’t sure if he’d been hit or not. The next shot struck directly in front of his face, spraying sand and debris into his eyes, temporarily blinding him. By now the Japanese were so close Marvin could feel the muzzle blasts from an enemy rifle and felt the last shot plowed into his back near his buttocks.

“Jesus Christ, I’m hit!” he screamed.

“Shut up! We’re all hit!” replied the corpsman.

He would find out later that his unit had been caught in a Japanese ambush consisting of 27 gun emplacements.

Marvin was dragged out by the aid men. When his buddies saw him they yelled, “Hey, Captain Marvel’s been hit in the ass!”

Crawling and stumbling, Marvin, with a group of walking wounded, headed back toward the battalion aid station. On the way, more men fell to Japanese bullets. Marvin clung to his Colt .45 in case he needed it in a hurry. He was still in shock, and the pain had not yet set in by the time he reached the rear and received his first morphine shot.

But just then the Japanese counterattacked again and the entire rear area was cleared as fast as possible. Marvin was one of the last to leave, on a stretcher lashed to a jeep under fire. Back at the beach, he was loaded into a Landing Craft, Mechanized (LCM) headed for the hospital ship Solace. The first thing he remembered after all the grime and blood of combat was looking at the bright, shiny shoes of a corpsman.

Lee Marvin would receive treatment in 13 hospitals for a 9-by-3-inch hole that had severed his sciatic nerve. He received the Purple Heart, of course, but the nightmares would continue for a long, long time.

Many more stars served in or survived the war, but to cover them all would take volumes. This was merely a sampling. Whether volunteering for combat or getting drafted, fighting as a soldier or dodging bombs as a civilian, World War II profoundly affected Hollywood’s leading men and women. We will always remember them for their roles on screen—we should also remember them for their roles and service off screen.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments