By Eric Niderost

On June 19, 1778, Continental soldiers marched out of Valley Forge, happy to leave the rough wooden cabins where they had spent a miserable winter; cold, hunger, and disease had been their constant companions. Regiment after regiment filed out, marching in cadence to fifes and drums. General George Washington was with them, dressed in his familiar blue and buff uniform, his face shining with a dignity that commanded respect.

To the casual observer, the American troops looked much as they did when they arrived at Valley Forge, exhausted and dispirited by a string of defeats at Brandywine and Germantown. Some regiments were well dressed in regulation uniforms of blue or brown. Others wore civilian dress or fringed hunting shirts, smocks that Washington approved as a good substitute for uniforms. Yet on closer inspection, there was a vital difference: the Americans were marching out in tight formations, their movements those of disciplined soldiers, not armed civilian rabble. They exuded pride in themselves and their regiments, something that would not have been possible a mere six months earlier.

The European Influences of the Continental Army

There were two major reasons for this martial metamorphosis: good news from Europe and the efforts of an obscure Prussian officer who had rallied to the American cause. A few weeks earlier, the camp had been galvanized by news of an impending French alliance. France, still smarting from its disastrous defeat at British hands during the Seven Years’ War, was now only too happy to openly aid the American rebels.

The army’s enhanced morale had also been boosted by the efforts of Baron Friedrich von Steuben, a Prussian-born career officer who consolidated the different military drills used by American units into one comprehensive manual, and followed with rigorous training for all soldiers, including officers. Steuben wrote to a European friend about his experience training the Americans: “You say to your soldier ‘Do this,’ and he does it. But I am obliged to say to the American, ‘This is why you ought to do this,’ and then he does it.”

Valley Forge had been well named. A new, more professional army had been created there, a hardened instrument shaped and hammered by Steuben on the anvil of adversity. But this new metal, an alloy of American individualism and European discipline, had yet to be tested. The next few weeks would determine if the American army was tempered steel or brittle tin.

The Continental Army marched out of Valley Forge in reaction to enemy movements. The British, still thinking along European lines, were disappointed to find that their nine-month occupation of Philadelphia had given them little beyond snug winter quarters. As Washington observed with great prescience, “The possession of our towns, while we still have an army in the field, will avail them but little.”

Disagreement Between Washington and Lee

General Sir Henry Clinton, the new British commander, was acting under orders from London to evacuate Philadelphia and withdraw to New York. There was now the very real threat that the French might blockade the Delaware River and bottle up the British army in Philadelphia. New York, 100 miles away, was more easily supplied by the Royal Navy. Clinton also was concerned about the several thousand Tories—Americans still loyal to the crown—who lived in Philadelphia. The Tories had supplied much-needed information at times, and some loyalists had fought in the ranks alongside British forces, but in essence the Tories were millstones around the British Army’s neck. Loyalist civilians had to be protected from their rebellious neighbors, and too often they ended up as military encumbrances.

About 3,000 Tories and most of the British cavalry were loaded onto waiting ships for the passage down the Delaware River. The bulk of the British army would proceed by land, trudging across New Jersey to rendezvous with the British fleet near South Amboy. From there, the redcoats would be ferried to safety on Staten Island.

It took the British seven hours to cross the Delaware, endlessly shuttling soldiers in flat-bottomed boats against the steady current. Once assembled on the Jersey shore, they began their march across the rebel state. It was warm for June, and the burning sun that hung in the sky gave ample warning of the scorching temperatures to come.

Washington had already decided that some kind of offensive action should be taken, but he assembled a formal council of war to sound out his subordinates. Army Quartermaster Nathaniel Greene, one of Washington’s best fighting generals, advised attack, as did the ever-pugnacious Maj. Gen. “Mad Anthony” Wayne. The army was in fine fettle, said Wayne, buoyed by the French alliance and a newfound sense of pride. Now was the time to attack.

But Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, Washington’s senior subordinate, disagreed. Lee had been a professional soldier in the Seven Years’ War, gaining experience in both Europe and America. Although he now sided with the rebels, he never forgot that he had once held the King’s commission—and never let anyone else forget it, either. He considered the Continental Army ill disciplined and slovenly in comparison to the British. He failed to see the vast improvements Steuben had made.

Lee also looked upon Washington with ill-disguised contempt, once claiming the Virginian was not fit to command a sergeant’s guard. Washington was well aware of Lee’s disdain but tended to overlook such slights for the sake of the country. Like him or not, Lee was an experienced professional when such men were a scarce commodity on the American side.

The Broiling March from Allentown

Since opinion seemed to be divided, Washington decided to compromise: he would send Colonel Stephen Moylan’s 4th Continental Dragoons to nip at the British heels and harass them as much as possible. Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. William Maxwell’s New Jersey militia, fighting on their own turf, would make life miserable for the marching redcoats. Colonel Daniel Morgan, the legendary “Old Wagoner,” would also come along with his riflemen.

Washington would follow with the main body of the army. The Virginian still hadn’t given up on the idea of a major engagement with Clinton. The Americans were far less encumbered by baggage—one of the few advantages of being relatively poor in material things. That meant that the Continental forces could march much faster than their adversaries. If fortune smiled on them, Washington could get ahead of the British, occupy the high ground, and take them on in a major engagement.

It looked as though Clinton was playing right into Washington’s hands. There were reports that Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, the victor at Saratoga, was coming south to reinforce Washington. Not wishing to expose his flank, Clinton decided to change direction. Instead of South Amboy, he would march his long-suffering army northwest toward Sandy Hook. It made sense on paper, but the reports about Gates were false and the change of direction would make life at lot more difficult for the British troops.

Advancing to Allentown, the British and their German mercenaries traveled along two roads that were more or less parallel. Lt. Gen. Charles Lord Cornwallis led a column along the westernmost road, acting as a kind of buffer to shield the baggage train plodding along the eastern road. Hessian General Wilhelm von Knyphausen and his troops were with the baggage train.

At Allentown, Clinton had to pause, reordering the line of march to account for the single road. Now Knyphausen would lead the column, the baggage train would follow, and Cornwallis would command the rear guard. The British set off again, even as the temperatures began to soar. As the sweltering days passed, the mercury climbed well into the 90s, with no relief in sight. The shadowing Americans also suffered, but to a degree they were better acclimated to the heat. Then, too, Continental officers allowed their men to strip off their coats and shirts in the heat.

The tightly disciplined British soldiers were not so lucky. They wore wool uniforms and carried upwards of 60 pounds or more in packs and equipment. Their ubiquitous Brown Bess .75-caliber smoothbore muskets alone weighed nearly 10 pounds each. The German mercenaries fared no better, and perhaps even worse. They were just as heavily loaded down, and perspiring Hessian grenadiers found that their imposing metal-plated miter caps made literal frying pans in the broiling sun.

The British march became a nightmare, a sweat-soaked exodus though clouds of choking dust and heat. After the advance guard came the baggage train, a hodgepodge caravan of army wagons and private carriages, together with bakeries, laundries and blacksmith shops on wheels. No fewer than 1,500 vehicles jammed the road. A swarm of camp followers walked behind the baggage train, women and children so numerous that the procession looked more like a ragtag gypsy caravan than a professional army on the march.

The Americans did all they could to add to the discomfort They blocked the road with felled trees, destroyed bridges, and filled in wells with piles of stones. American sharpshooters continually sniped at the redcoats with deadly effect. Nature itself seemed determined to impede the British progress. At night there were heavy thunderstorms, turning the dusty road into a glutinous mire. When the sun rose, so did the temperatures, and there was little water to be had. By the dozens, British soldiers staggered to the side of the road and collapsed in a heap, victims of heatstroke. Many died where they lay. Others lay prostrate with exhaustion. Not even the threat of a flogging could move them.

A Paralyzed Command

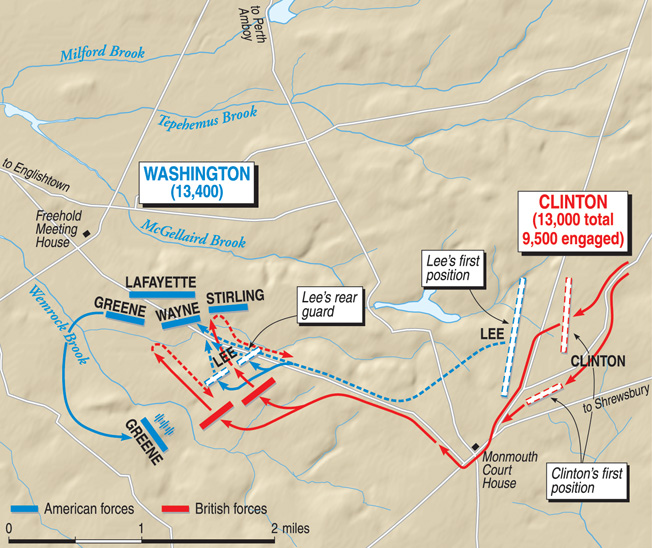

By the morning of June 26, the British army had reached Monmouth Court House. Clinton decided to let the army rest from its ordeal, and orders were given to stay at Monmouth for the time being. In the meantime, Washington had decided on a bold stroke. An advance corps would move forward and pounce on the British rear guard. Washington would then bring up the main body in support.

Lee still felt that any action was folly. Why risk another defeat? Better to wait for the French to come—they were the true professionals—and in the meantime sit tight. Lee had been released from British captivity earlier that year, and so had missed Steuben’s training program and its inspiring effect on the Continental troops. His thinly disguised contempt for Washington and the “Yankees” was as strong as ever. As a former British officer, Lee was also under threat of being branded a deserter from the British ranks—a status that might lead to the hangman’s noose.

Washington decided to go forward with his plan, but Lee refused to command it. Washington handed the advance guard command to elaborately named Maj. Gen. Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, the marquis de Lafayette. Still only 20 years of age, Lafayette had won Washington’s confidence. Lafayette had the kind of aggressive spirit that was needed for an operation of this kind. But when Lee heard that there would be 6,000 men in the advance corps, he changed his mind. That number of troops should go to the senior man, and Lee told Washington so in no uncertain terms. One of Washington’s few weaknesses was a strong sense of propriety, a sense of being a gentleman and of doing the right thing even if it was not in his own best interests. He acquiesced. Lee would command the advance corps, even though he had repeatedly voiced objections to any offensive action.

On Saturday, June 27, Washington summoned Lee to his headquarters at Henlopen, New Jersey, a few miles south of Englishtown. Lafayette was present, as well as Generals Wayne, Maxwell, and Charles Scott. Washington ordered Lee to attack the British rear guard and flank at Monmouth before they resumed their march to Sandy Hook. Washington left the operational details to Lee, which was standard procedure.

But once Lee returned to his own tent, a strange sort of inertia seemed to paralyze him. His subordinates waited for orders, but none came. There was no consultation, no poring over maps, and certainly no battle plan. Around midnight Lee received another order from Washington, directing him to dispatch New Jersey militia commander Philemon Dickinson to make contact with the enemy.

Lee did as he was told, but little else. Dickinson was sent on his way, but when Lafayette came into Lee’s tent for orders at 4 am on June 28, he found that Lee had none to give him. Dickinson was out on a limb; Lee still hadn’t formulated a battle plan. It was obvious that Lee was only going through the motions. He had predicted disaster—and with him in command, defeat seemed likely to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Lee’s command-and-control skills were weak, almost nonexistent. Most of his officers—even the boyish Lafayette—were good soldiers, and some like Anthony Wayne had solid reputations as fighters. But as subordinates they needed guidance and direction—crucial elements that Lee seemed unwilling or unable to supply.

Lee’s Late Attack

In the meantime, Dickinson was scouting out the terrain in the general vicinity of Monmouth Court House. As the main road continued, there was the West Morass, sometimes called a ravine, of the Spotswood Middle Brook. It was boggy area spanned by a wooden bridge. Beyond West Ravine, Comb’s Hill loomed to the south and right. The road then went across Middle Ravine before finally coming to Monmouth, where it merged with the road to Allentown, which led in turn to Briar Hill. Just before Briar Hill, the thoroughfare branched off toward Middletown and Sandy Hook.

The British advance column under Knyphausen roused itself and started to march out of Monmouth in the early morning hours. Dickinson noted the movement and sent urgent messages to both Washington and Lee. As soon as Washington received the missive, he responded with alacrity. Ordering his men to drop their packs alongside the road for greater speed, Washington pressed forward to Englishtown, intent on joining Lee.

Meanwhile, Lee was advancing at a leisurely pace. As he made his way forward, skirmishing broke out between New Jersey militia and British soldiers in the Monmouth vicinity. The great battle was beginning. Dickinson sent another message to Lee saying that he was engaged and that the British seemed to be falling back. Other reports said the British were advancing.

Confused and irritated by the lack of information—information he himself had failed to gather—Lee wasted an hour trying to decide what to do, then belatedly opted to mount an attack on the British rear guard. Units were to move to the right and left, enveloping the supposedly unsuspecting redcoats, while Wayne mounted a feint attack that would distract them from the developing trap. Lee was briefly exultant, feeling that he might surround and destroy Cornwallis and his troops.

Things began to unravel almost at once. Confusion reigned, in part because Lee had failed to inform his officers of his intentions. When Lt. Col. Eleazar Oswald’s artillerymen went back to replenish their ammunition, many Continental soldiers, including the New Jersey militia under Scott and Maxwell, mistook this movement for a withdrawal and began to retreat themselves. A kind of domino effect began, as different Continental units saw others falling back and began to feel isolated. Before long they, too, joined the general stampede. Some regiments retreated in good order, others in something akin to panic.

Lee was still contemplating his destruction of the British rear guard when the truth dawned on him—his forces were falling back. His ambitious enveloping scheme in shambles, Lee briefly considered making a stand at Monmouth Court House. When it was pointed out to him that the buildings were all made of wood—easy targets for fire—he abandoned the idea. Half defeated even before he started, the inept general ordered a retreat.

“Damned Poltroon”

When the Americans first attacked, Clinton thought that they were after his vulnerable baggage train. Already on the road to Sandy Hook, he doubled back with some of his finest troops, including the Grenadiers and Coldstream Guards. Clinton hoped that Washington would be stupid enough to come to Lee’s aid in the ground between the two morasses. With his back to the West Morass, Washington would be vulnerable to destruction.

It was nearing 1 pm when Washington approached the bridge over the West Morass at Spotswood Middle Brook. There he encountered a young and badly shaken fifer, who told a tale of headlong retreat. Washington could scarcely believe his ears, yet within a few minutes there was ample proof all around him—soldiers crossing the bridge and streaming to the rear, or fainting with heatstroke in the weeds alongside the road. Washington was dumbfounded, and so was his staff. Colonel John Laurens, one of Washington’s aides de camp, painfully recalled “all this disgraceful retreating, passed without the firing of a musket, over ground that might have been disputed inch by inch.”

There was no time to lose. Washington spied two regiments that had not yet crossed the bridge and immediately sent them into a nearby wood to gain time for the rest of the army to reform and regroup for battle. These two regiments, Colonel Walter Stewart’s 13th Pennsylvania and Nathaniel Ramsay’s 3rd Maryland, were to give a good account of themselves in the coming fight

Washington’s mere presence—tall, dignified, and exuding confidence and courage—gave his men a sorely needed morale boost. It was one of Washington’s finest moments. New Jersey Private John Ackerman recalled years later that he had lost his shoes crossing one of the bogs, and his regiment was disordered by the headlong retreat.

Then Washington appeared and the men got themselves into some semblance of order. “Can you fight?” the general asked, and the troops responded with three cheers. A witness to the incident, Lafayette recalled that “I thought then, as now, that never had I beheld so superb a man.”

Washington saw a slim man on horseback ride toward him, his uniform covered with dust. It was Lee, apparently pleased that by retreating he was saving his army from a dire fate. Washington was livid with rage. “What is the meaning of this, sir?” the commander in chief demanded. “What is all this confusion and retreating?” Lee, shocked by Washington’s angry tone, could only stammer, “Sir?” Regaining his composure, Lee explained that his orders had not been followed. Anyway, he observed, American troops were not able to stand against the British. This last remark rekindled a terrible rage in Washington. “Sir,” he replied with considerable passion, “They are able, and by God, they shall do it!” Lafayette heard Washington call Lee a “damned poltroon”—the only time he ever heard Washington curse.

Washington’s Delaying Action

Washington ordered Lee to gather what men he could and fight a delaying action, much like Stewart and Ramsey were doing in the wood to the east. Lee assembled some 800 men behind a hedgerow. The pursuing redcoats, who were 15 minutes away or less, comprised some of the British army’s most elite units. Traditionally each regiment had a company of grenadiers, tall, strong men who were placed on the right of a battle line. During the Revolution, the British tended to consolidate all regimental grenadier companies into their own battalions. This was true at Monmouth, where Clinton was moving forward with the 1st and 2nd Grenadier battalions. Clinton also had the 1st and 2nd Guards battalions, the cream of the British Army. For cavalry support he had the 16th and 17th Light Dragoons. The British commander was so eager for battle that he rode around the field like a “Newmarket jockey,” in the words of one observer.

Stewart’s and Ramsay’s men were attacked by the 16th and 17 Light Dragoons, but steady volleys emptied saddles. The Marylanders and Pennsylvanians were aided by a Virginia regiment (the consolidated 4th/8th and 12th Virginia). Finally, British pressure forced the Continentals from the woods. Ramsay, on foot, was charged by a dragoon coming at him at full tilt with a pistol. He coolly sidestepped the onrushing horse and cut down the dragoon with a quick flash of his saber. After the trooper tumbled from the saddle, Ramsay coolly mounted the horse and rode toward the British formations. In a remarkable display of courage, he galloped in front of the British lines, blood-daubed sword in hand. It was as if he were challenging the entire British Army to a duel. The British surrounded Ramsay and took him prisoner. Clinton later pardoned and released the American officer as a tribute to his bravery.

The wooded area had fallen to the British; it was up to Lee’s men at the hedgerow to stem the scarlet tide. The hedgerow defense was manned by Colonel James Mitchell Varnum’s brigade, supported by Colonel Henry Livingston’s 4th New York. Initial artillery support was provided by Oswald’s guns, augmented by others directed personally by Washington’s chief artillerist, Henry Knox. On the British side, the grenadier battalions were approaching the hedgerow at a steady clip.

The advance was not an unalloyed triumph, however. Lieutenant William Hale of the 45th Regiment of Foot, who was attached to the 2nd Grenadier Battalion, recalled the harrowing experience in a letter a few days later. “We proceeded five miles down a road composed of nothing but sand which scorched though our shoes with intolerable heat,” he wrote. There was no water, and even the elite troops had trouble maintaining the pace in such an oven. He added, “The sun [was] beating on our heads with a force scarcely to be conceived in Europe.”

Flushed with the heat and the exertions of the march, many grenadiers began dropping along the side of the road, throats dry and lips cracked with thirst. The road was “strewed with miserable wretches wishing for death,” and indeed, many did die from heatstroke. Hale’s opinion of Clinton was less than complimentary. In his view, the Continentals had lured the British into a trap, and Clinton had eagerly risen to the bait. The commander of the 2nd Grenadier Battalion, Lt. Col. Henry Monckton, had scanned the Americans with his telescope and pronounced them “provincial” troops—that is, militia. It was a fatal mistake for Monckton, who soon was shot down and dragged into the American lines to die.

“We Rushed on Amidst the Heaviest Fire I Have Yet Felt”

The Continentals calmly waited for the command, then raised their muskets as one man. A volley crashed out, the leaden hail striking the redcoats with a fury, accompanied by a storm of grape from the artillery. Said Hale, “We rushed on amidst the heaviest fire I have yet felt.” Clinton, caught up in the action, cried, “Charge, grenadiers, charge, never heed forming!” The British troops surged forward, losing all cohesion, as each company tried to outrace all others. The American volleys stopped the advance, at least temporarily, and the opposing forces began to trade volleys at point-blank range. At 20 yards or so, even the notoriously inaccurate smoothbore muskets could be deadly.

The slugfest lasted about five minutes, with the Continentals standing their ground against some of Britain’s finest troops. But when the British Light Dragoons broke through the hedgerow to the south, there was nothing left to do but begin an orderly withdrawal. Well-served Continental artillery, positioned to the rear of the hedgerow, poured more grapeshot at the British grenadiers before they too limbered up and made their escape. The grenadiers tried to cut off their retreat, but all American soldiers managed to cross the bridge over West Morass to safety. The last man to cross was Lee, who was ordered to the rear by Washington to rest and reform the battered regiments.

While the Continentals were buying time at the wood and hedgerow, Washington was organizing the main body into a defense at Perrine Hill. Troops there included the Pennsylvania and Massachusetts men of Maj. Gen. William Alexander, Lord Stirling. Lafayette was deployed with four brigades plus the 1st and 2nd New Jersey regiments in a second line of defense to cover Stirling’s left flank north of Spotswood North Brook.

At one point in the battle, Lt. Col. Aaron Burr urged his soldiers forward, but his horse was injured and he fell from the saddle. Burr wanted to continue the attack, but Washington decided otherwise. Burr was shaken up and seriously ill from the effects of heatstroke. Monmouth was to be his last battle; shortly thereafter he resigned his commission. Not far away on the field was his future rival and victim, Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton.

“Battle of the Parsonage”

At 1 o’clock, the British brought up a battery of 10 guns and placed them between Wikoff and Parsonage farms, about 1,000 yards from the American position, Knox brought up 12 guns, which soon flamed and recoiled in counter battery. The artillery duel was one of the heaviest of the war, with cannonballs coming so close to Washington that his uniform was splattered with mud from near misses. Washington exposed himself constantly during the fight, and the thick clouds of gray-white powder smoke that usually shrouded 18th-century battles was his only protection from the enemy. At times he was only 20 to 30 feet from the British line. His magnificent white charger, worn out by travel and heat, died from the effects of the sun and was replaced by a chestnut mare.

The American guns at Comb’s Hill were particularly galling to the British. It was a literal cross fire that plowed into red-coated ranks with bloody abandon. One cannonball knocked the muskets from the hands of an entire file of British soldiers as they came into its path of trajectory. The British tried a series of probing attacks without success. When he could see his advances were going nowhere, Clinton came to his senses and began to withdraw. At one point men, of the 42nd Highlanders—the fabled Black Watch—found themselves assailed on the right and tormented by American cannonballs in the front.

Blocked by a fence, the Continentals had to take the time to tear down the obstruction. While the fence was hastily pulled down, skirmishers were sent ahead to slow and harass the kilted warriors. Joseph Plumb Martin was one of those skirmishers. Passing through a nearby orchard, Martin recalled seeing a number of British dead. It was a testament to American training and the general accuracy of their artillery.

General Wayne and his men crossed the West Morass Bridge and attacked the 1st Grenadier Battalion in what came to be known as the “battle of the parsonage.” When the battered British began to rally, Wayne’s men took cover in the parsonage’s numerous buildings and yards. Frustrated by the stubborn American defense, the British broke off the action and retreated. The Battle of Monmouth was over.

The Court-Martial of Charles Lee

By nightfall it was clear that both sides were too exhausted to renew the fight on the morrow. The British withdrew to Sandy Hook with no further serious molestation. Washington, striding the battlefield like a lord of war, came upon Lafayette sleeping beneath an old oak tree. The American commander pulled off his cloak and threw it over the young Frenchman, joining him in a well-deserved rest.

Washington decided not to pursue Clinton and renew the battle. Five days later, Howe’s ships transported Clinton’s army to New York, less than week before the much-feared arrival of the French fleet under Admiral Charles Hector, Comte d’Estaing, off Sandy Hook. Both Washington and Clinton minimized their losses. The official British figures listed 361 casualties—67 killed in action, 59 dead of heatstroke, 170 wounded, and 65 missing The American figures disputed this, claiming over 200 British dead and another 576 Hessian and British deserters.

The final casualty of the Battle of Monmouth was Charles Lee. After an acrimonious exchange of letters with Washington, Lee was court-martialed and charged with disobeying orders, running from the enemy, and disrespecting his superior. Found guilty of all charges, he was suspended from command by the Continental Congress. Lee died, still protesting his innocence, in a Philadelphia boardinghouse on October 5, 1782.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments