By O’Brien Brown

The samurai warrior sat in the middle of the dueling grounds in the village of Hirafuku, Japan, glaring at the spectators who had gathered around him. The day before, the samurai had posted a challenge to anyone wishing to fight him, but some brazen boy had blackened out the challenge and scrawled his own name across it. To erase this dishonor, the samurai insisted on a public airing. The year was 1596.

As a monk tried to explain away the prank, the boy suddenly rushed in, shouting, “Come on, let’s fight!” and attacked the startled warrior with a sword. Jumping to his feet, the samurai slashed at the youth with his short sword as the boy lunged forward, throwing the man over his shoulder. Quick as lightning, the youth struck the warrior between the eyes, stunning him. The samurai struggled to get to his feet, but the boy smashed him repeatedly on the head until the man dropped dead in the dirt. The crowd hooted and applauded in admiration. The boy, Miyamoto Musashi, was just 12 years old. And he had defeated the battle-tested samurai using nothing more than a wooden bokuto sword.

Miyamoto Musashi: Sword Saint

Musashi’s first duel displayed the qualities that would light his name for future generations as one of the greatest swordfighters in Japanese history: surprise, boldness, strategy, fury, and skill. Musashi would go on to emerge victorious in more than 60 duels, most to the death. Much more than a fearsome swordsman, however, Musashi was also an exquisite painter, sculptor, calligrapher, teacher, writer, and philosopher. His book Gorin no sho, variously translated as The Book of Five Rings, the Book of Five Elements or Essays on the Five Circles, is considered a classic. Universally revered, Musashi is known as a kensei, or Sword Saint, in Japan.

Perhaps no other fighting man has been so completely transmogrified by the film industry as the samurai, grotesquely distorting modern perceptions of medieval Japanese warfare. On the screen, handsome silk-robed actors elegantly glide through the air to bloodlessly bring down their foes with a subtle flash of steel. The reality was quite different—hand-to-hand combat featuring spears, swords, arrows, and flintlocks is rarely pretty.

As Japan’s warrior elite, the samurai were recognizable by their right to wear two swords: the long katana and the short wakizashi. A samurai’s life was devoted to Bushido, the way of the samurai, summed up by warrior Tsunetomo Yamamoto: “I have found the essence of Bushido: to die!” If they served a lord, it was with utmost loyalty. A warrior was expected to commit seppuku, or ritual suicide, should his master die. His life was one of ritual, duty, honor, and warcraft.

With the ascent of Ieyasu Tokugawa as shogun in 1600, Japan enjoyed more than 250 years of relative peace, broken by sporadic rebellions. For the samurai, this meant abandoning warfare while maintaining their identity as warriors. This was the world into which Musashi was born. Much of his early life is unknown or contradictory. He was born in 1580 or 1584, in either the village of Sakushu or Banshu in Harima Province, near Kyoto. His father is thought to have been Hirata (or Miyamoto) Munisai, an expert swordsman who served a local lord.

Bennosuke Earns His Name

Young Musashi was called Bennosuke; he would earn his adult name upon entering manhood around the age of 12. His mother died when he was a toddler, and Bennosuke was raised by his uncle and his father’s new wife. When the marriage ended, Bennosuke grew up in another household after his step-mother remarried. The boy was seething with wild energy and was strong-willed and difficult to handle.

Bennosuke was harshly trained in the fighting arts by his father. One day, relates a period text, Musashi’s father lost his temper and threw a knife at him. Bennosuke dodged it with a slight movement of his head. It was a rough upbringing for brutal times. Four years later, the boy fought the duel described above. Afterward, the triumphant Bennosuke changed his hairstyle, dress, bearing, and name, choosing Miyamoto Musashi—Miyamoto being his father’s village.

In 1599, the teenaged Musashi hit the road, leaving all his belongings behind. At this time, talented young men often desired to work for a lord. They lived in barracks or their own homes, paying for most of their equipment. Musashi, however, chose to become a rônin, a lordless sword-for-hire paid in koku, or portions of rice. He wandered throughout Japan on journeys called musha shugyo, “traveling for improvement.” Musashi slept out in the open, hunted for food, and earned money by providing services to townsfolk, a lifestyle that toughened both body and mind.

Musashi’s Psychological Combat Style

Always seeking perfection, Musashi trained in swordsmanship from sunrise to sunset. “A thousands days of training to develop,” he wrote, “ten thousand days of training to polish.” Like other rônin, Musashi sought duels against other warriors to hone his skills and make a name for himself. Warriors would post a notice in a town challenging someone to fight and a time and place would be arranged. Sometimes they would write a letter outlining the conditions of the match. If a warrior met another wandering samurai, he could ask him to fight. If the man was a martial arts master, the challenger would often have to fight the master’s disciples first. These duels, usually watched by referees and conducted in front of an audience, were deadly combat, resulting in serious maiming, crushed skulls, severed limbs, sliced torsos, and beheadings. The fighters used neither shield nor armor; they dueled in their robes.

In 1600, Musashi fought Akiyama, an expert of great power, killing him as quickly as one can turn over his hand. That same year, he apparently participated in the Battle of Sekigahara. After this, he took up his travels again, fighting 60 duels in 10 years, averaging a fight every two months. “I did not lose even once,” he wrote. To survive for long, however, professionals like Musashi normally avoided warriors of their own or a superior skill level.

Musashi developed a unique style from these deadly struggles, described in brutal detail in Gorin no sho. He would ram his opponents, sometimes killing them on impact, throw dirt in their faces, maneuver so that the sun was in their eyes, and stab at their faces. Rhythm, self-awareness, and perceiving an adversary’s intentions were vital. Musashi sought to psychologically destroy his opponents first; physically destroying them was an additional detail. “Your attitude,” Musashi said, should “be superior to that of others … you can conquer by virtue of your own mind.”

Musashi studied, mastered, and then broke the rules of different fighting styles. His aggressive, fluid techniques were bewildering to his opponents, who expected a certain tradition-based behavior. Most died without comprehending what had hit them. Often Musashi’s weapon was a bokuto. He strove to kill with his first blow; if this missed he would use its energy to follow through and strike anything—a hand, a foot—to weaken his opponent’s ability to continue. It mattered little to him if he was up against one or 30 opponents. Few could withstand the single-minded ferocity of his attack. Musashi was creative, intelligent, brave, and self-reliant. “Respect the gods and Buddha,” he counseled. “But do not depend on them.”

An eccentric iconoclast, Musashi was an imposing man. Texts describe him as standing nearly six feet tall, with a powerful frame and well above the average strength. During his entire life he did not comb his hair or take a bath. During his prime, his hair hung down to his belt. As a rônin, Musashi lived a hard and barren life; he never married and had no children except three adopted sons. “Do not let yourself be guided by the feeling of love,” he wrote in a philosophical text, The Way of Walking Alone. “Do not harbor hopes for your own personal home.” He dedicated his life to the attainment of perfection.

“School of the Shining Circle”

During his travels, Musashi created a technique called Enmei Ryu, or “School of the Shinning Circle.” In this technique, he wielded a large and short sword to dazzle and baffle his opponents. By crossing the swords, he formed a scissors to immobilize or disarm his foes, then he would cut them down. Additionally, Musashi was skilled in shuriken, the art of throwing a knife or short sword. If Musashi’s adversaries ran or fled, none succeeded in escaping him. His throws had the power of a strong bow, and he never missed his mark.

One text describes a duel in which Musashi fought Shishido, an expert in the kusari gama, a sickle attached to a chain with a steel weight at one end: “Before Shishido could strike with his sickle, Musashi threw his short sword, which pierced Shishido’s chest. Immediately closing in, Musashi cut him down with his long sword. Shishido’s disciples seized weapons and attacked Musashi. Under the brunt of Musashi’s counterattack, they dispersed in all directions.”

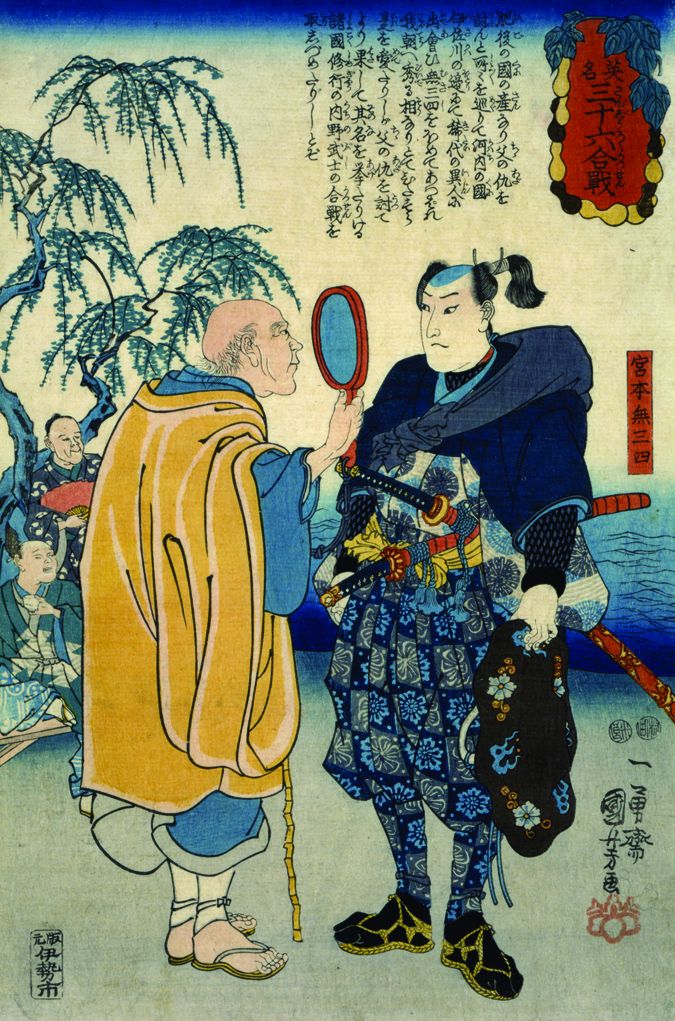

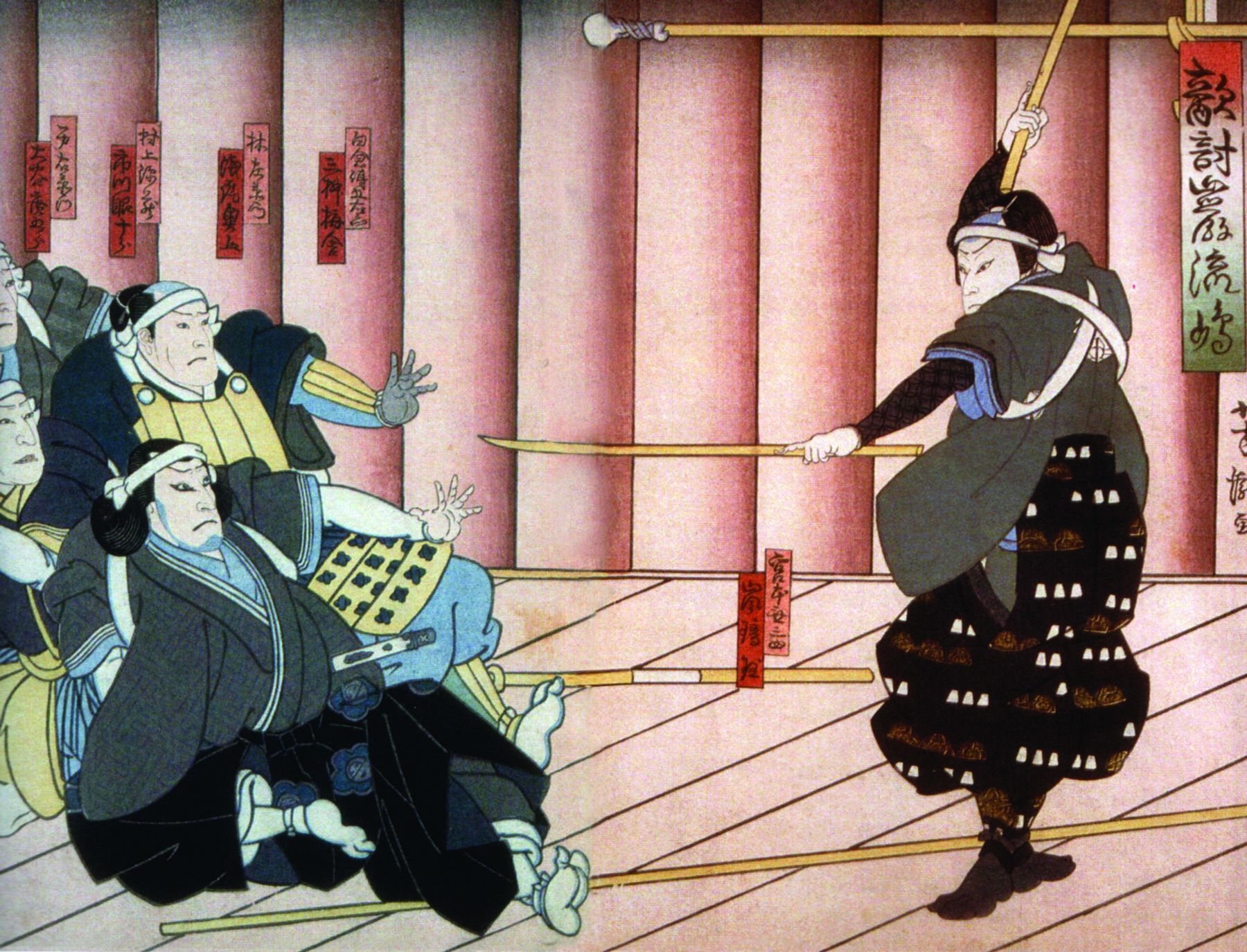

In 1604, Musashi fought famous duels against three Yoshioka brothers—Seijuro, Denshichiro, and Matashichiro—samurai from the respected Yoshioka School of swordsmanship near Kyoto. After an exchange of letters, a match was arranged pitting Musashi against Seijuro. True to form, Musashi arrived late; Seijuro became unnerved. The fight began and the two men circled each other, both armed with wooden swords. Musashi bashed Seijuro on the shoulder, knocking him out and crippling his arm; he never fought again. To avenge his older brother, Denshichiro challenged Musashi, who accepted. On the day of the match, Musashi again arrived late, greatly irritating Denshichiro, who was armed with a long staff that had a steel ball swinging from its end. During the fight, Musashi disarmed Denshichiro with his wooden sword, then killed him with his own weapon.

The Yoshioka family was outraged, and 12-year-old Matashichiro was made to challenge Musashi, who again accepted. This time, however, Musashi arrived at the grounds early and hid among the bushes. He watched as dozens of heavily armed Yoshioka men arrived, intent on killing him. Thinking quickly, Musashi calculated that, if he could take out Matashichiro, his followers would panic. Musashi sprang forward, killed the boy with a single blow, and made a fighting escape. It was a masterful display of strategy and boldness.

In 1612, when he was about 30 years old, Musashi sought a match with Ganryu Sasaki Kojiro, a sword stylist. The bout took place on a small island off Kokura. Kojiro wielded a nodachi, a long two-handed sword. Musashi came to the duel late and unkempt. After a short fight, he smashed Kojiro on the head with a bokuto, killing him. Musashi’s detractors were outraged by his “disrespectful” conduct; his supporters delighted in his intelligent strategy. “Seeing,” Musashi wrote, “is more important than looking.” In other words, sense and perceive your opponent’s moves before the fight begins instead of concentrating on his weapons or actions once in combat.

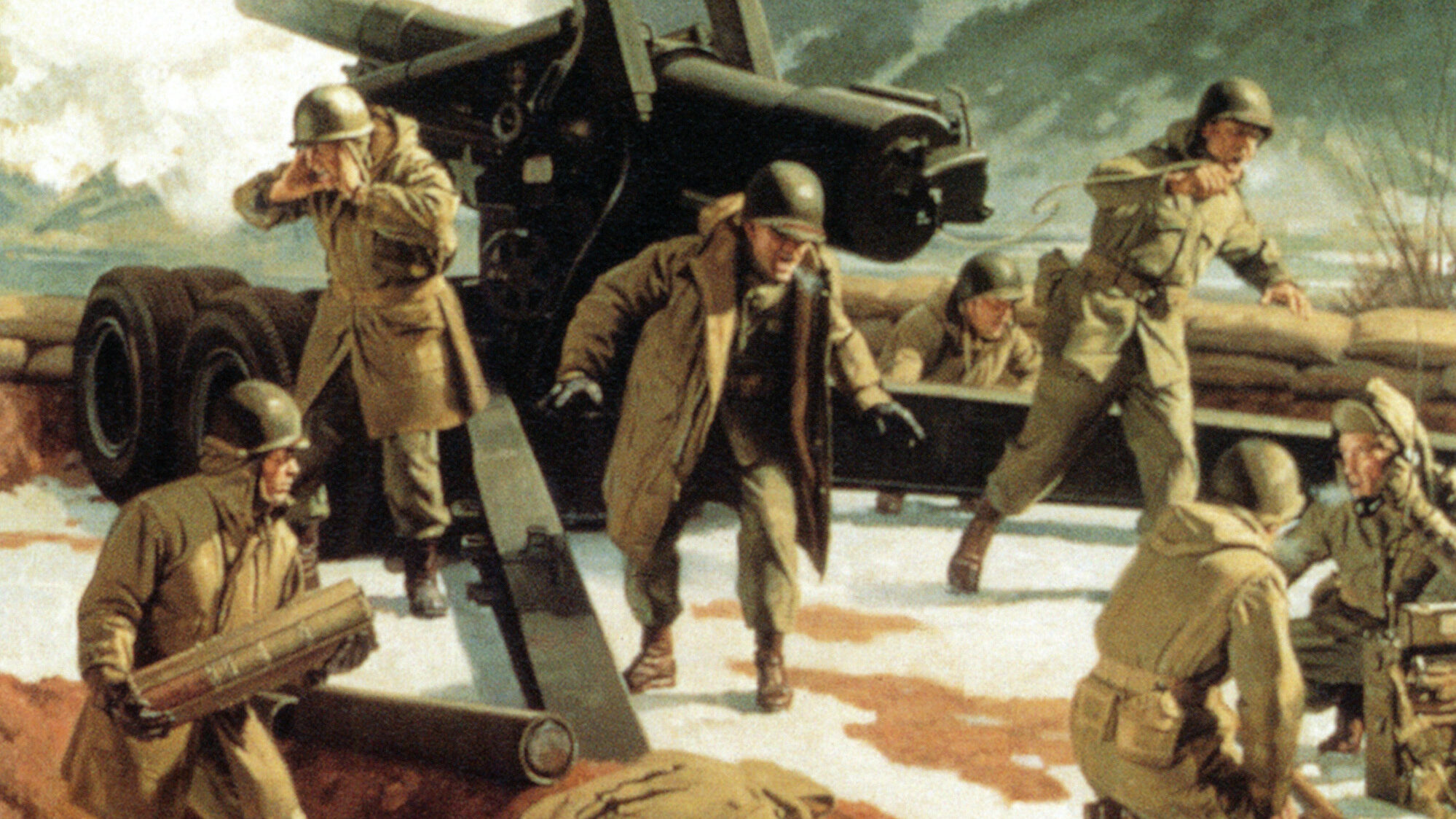

In addition to dueling, Musashi also participated in several battles, including the siege of Osaka Castle in 1614-1615. In 1637, he apparently fought at Hara Castle during a rebellion, where he was wounded several times. In a letter from 1640, Musashi proudly wrote: “I have participated in battles six times. Four times out of six, I was in the van, leading the army into battle.”

A Guest of Lord Hosokawa

From the age of about 30, Musashi changed. On his present path, he realized, sooner or later he would be cut down by someone younger, stronger, and quicker. And despite the subtleties of Zen philosophy and endless training, he knew that any enraged prepubescent teen with a warrior complex could take him unawares and dash out his brains with a piece of wood.

“When I passed the age of thirty,” Musashi wrote, “and thought back over my life, I understood that I had not been a victor because of extraordinary skill in the martial arts. Perhaps I had some natural talent or had not departed from natural principles. Or again, was it that the martial arts of other styles were lacking something?”

Now came a time of contemplation. Musashi composed poetry and created 25 paintings. He also made sculptures of wood and metal, and practiced the tea ceremony and calligraphy. He became excellent at kizeme—mentally dominating an opponent without killing him; he stopped participating in duels to the death.

Now came a time of contemplation. Musashi composed poetry and created 25 paintings. He also made sculptures of wood and metal, and practiced the tea ceremony and calligraphy. He became excellent at kizeme—mentally dominating an opponent without killing him; he stopped participating in duels to the death.

In 1640, Musashi sent a letter to Lord Hosokawa, who wished to meet the famous swordsman. “I have never been officially in the service of a lord,” Musashi wrote, “but I can be useful teaching the way weapons are used and what is suitable conduct on the field of battle.” Musashi stayed with Hosokawa at Chiba Castle in Kumamoto, as Hosokawa’s guest, teacher, and counselor. In 1641, Musashi wrote a work called the Hyoho sanju go, or “Thirty-five Instructions on Strategy.” When Hosokawa died that same year, Musashi devoted his life to writing and meditation, retreating to Reigando cave on Mount Iwato, southwest of Kumamoto. He felt his own end approaching.

In 1645, he wrote Gorin no sho, whose chapters are based on the five elements of Buddhism: earth, water, fire, wind, and emptiness. Taking up his brush once more, Musashi composed The Way of Walking Alone, 21 points to guide future disciples. One week later, “at the moment of his death,” relates a text, “he had himself raised up. He had his belt tightened and his wakizashi put in it. He seated himself with one knee vertically raised, holding the sword with his left hand and a cane in his right hand. He died in this posture, at the age of 62.” According to his wishes, Musashi’s hair was buried on Mount Iwato. His body, dressed in armor, was interred outside of Kumamoto so that, as he wrote, “I will protect the peace of the Hosokawa family.”

The Mystical Legends of Miyamoto Musashi

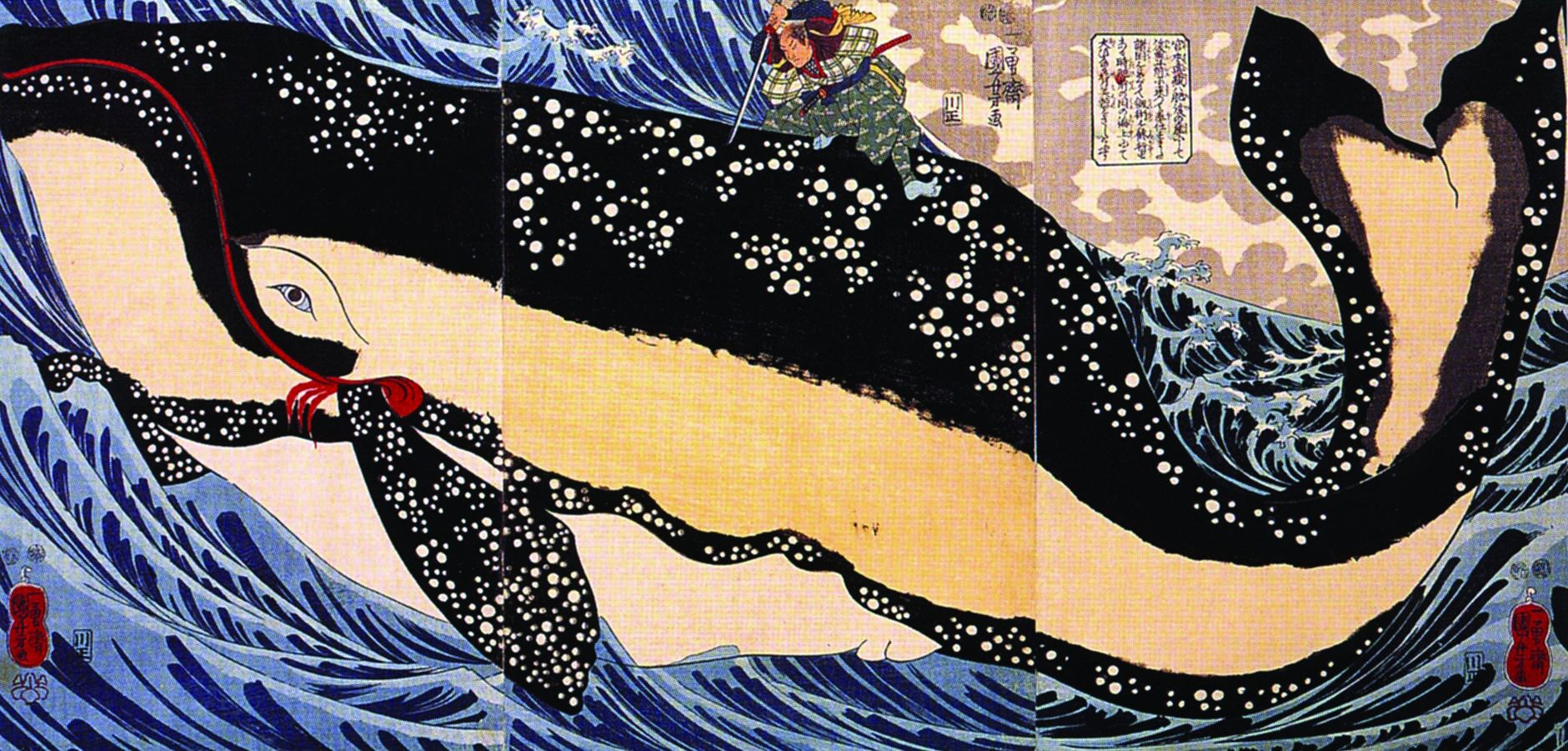

Musashi’s exploits have become shrouded by the mists of legend. Even during his lifetime, there were tales of him walking on water or killing mythological creatures. In the modern age, a best-selling novel, manga comic books, a television series, and more than 30 films have been made about his adventures. Musashi’s teachings are still pertinent. Gorin no sho is widely read by those seeking wisdom in all walks of life. Enmei Ryu boasts many active branches. He is probably Japan’s best-loved historical figure.

Musashi was an artist of the sword, the brush, the chisel, and the mind. He was a nonconformist in a highly conformist society, respecting the gods but putting faith in himself, working for lords but not under them, understanding the importance of tradition but being creative and original in his work and lifestyle. His greatness lay not in how many men he vanquished, but how he transcended killing and strove for the greater aspects of the heart, mind, and soul. At the end of his full life, the sublimity of creation trumped the lust for destruction.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments