By Hervie Haufler

As the 1930s unfolded, Adolf Hitler sought to avoid having Great Britain join the war he intended to launch. He saw the British as fellow Aryans who should be sympathetic to his ethnic policies and supportive of his antipathy toward the Bolsheviks of the Soviet Union. To keep from having the relationship with Britain possibly soured by the unmasking of German secret agents, he hesitated about creating a network of spies on British soil. The result was that when the war started, with Britain as a combatant, Germany had to play catch-up in the spy game.

Early German Spy Recruits

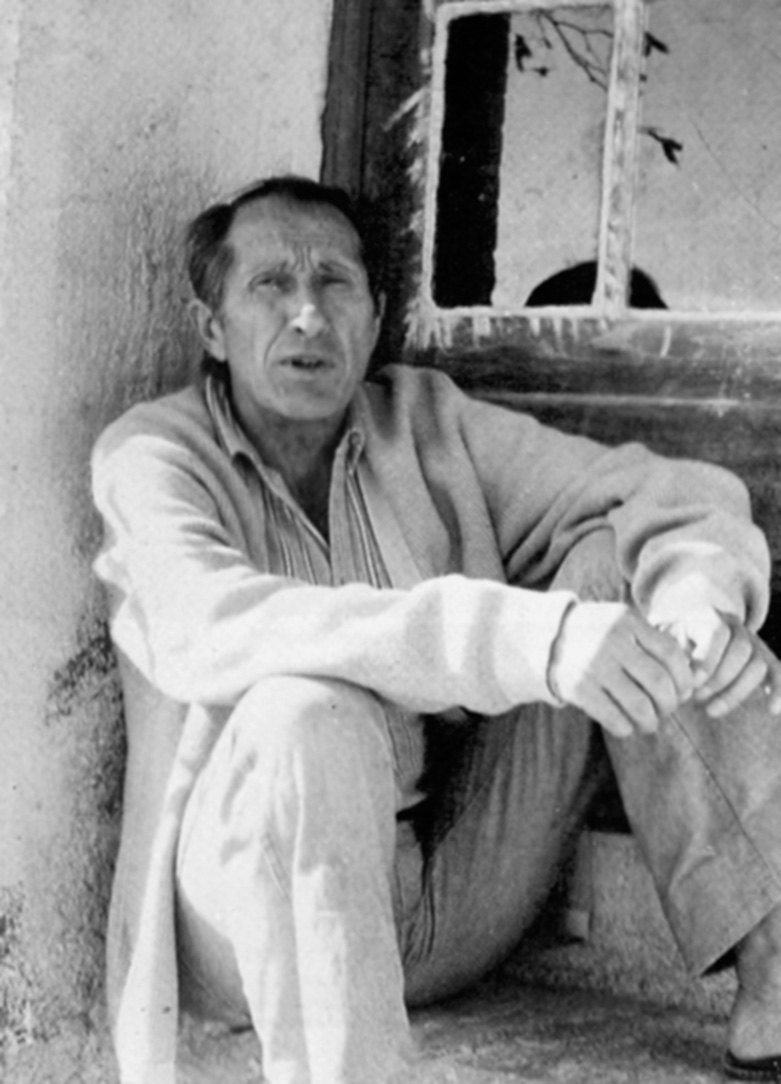

The Abwehr, German military intelligence, was forced to build upon its slim prewar beginnings. It did have one reliable informant, Arthur Owens. Owens was a Welsh nationalist who presented himself to German intelligence during the 1930s as bitterly opposed to the British. An electrical engineer whose firm did work for the British Admiralty, he was recruited by the Abwehr to provide useful information about the Royal Navy.

When the war began and the Germans seized the Channel island of Jersey, they found another willing spy in Eddy Chapman, whom the British had embittered by finding him guilty of crimes and imprisoning him on Jersey.

Still another recruit was a former Polish officer named Roman Garby-Czerniawski, who was so opposed to Communism that he was willing to become an agent for the fascists. The Germans sent him to Britain, where he became an officer in the Polish military in exile, a position that enabled him to report high-level intelligence to his handlers.

It was the same with Juan Pujol, a Spaniard strongly opposed to Bolshevism. Pujol not only filed his own reports from Britain, but established a network of sub-agents willing to work for the Nazis.

Dusko Popov was a wealthy young Yugoslav whose studies in Germany had convinced him of the rightness of the Nazi cause. As a businessman, he gained access into high British social circles, allowing him to ferret out information the Abwehr could otherwise not receive.

In addition, the Abwehr trained English-speaking Germans as spies and, by submarine, boat and plane, landed them in Britain. One of these, Wulf Schmidt, was seen by the Germans as such a useful agent that he was twice awarded the Iron Cross, both First and Second Class.

The Allies’ Double Agents

With such an extensive network of agents in place sending back reams of useful information, the Germans were confident that their needs for special intelligence were being met and that additional spies were not needed. For the Allies, one of the greatest benefits of the intelligence war was that none of these agents were what they purported to be. Every spy reporting to a German controller was a double agent, seeming to serve the Nazis while supplying more misinformation than truthful data.

True, Arthur Owens, codenamed Snow by the British, was Welsh, but any anti-British feelings he may have felt were not strong enough to make him serve the Nazis. It was the same with Eddy Chapman, codenamed Zigzag. His anger toward his captors was more of a pose than a reality. The secret desire of Poland’s Garby-Czerniawski, codenamed Brutus, was to avenge the Germans’ devastation of his homeland. The supposed anger against Communism professed by Pujol, codenamed Garbo, was merely a ruse; his real hatred was for the Nazis. When approached in Belgrade by an Abwehr officer who had been a school chum, Popov, Tricycle to the British Twenty (XX) Committee, slipped away to check with the British consul. He was told, to go along with the Germans, while in actuality he would be working for the British.

Germany’s Home-Grown Agents Do Poorly

The hurried training given Germany’s own assigned agents left them vulnerable to gaffes that quickly gave them away. One made the mistake of trying to use his forged ration book to pay for a meal in a restaurant. Another thought that when he was billed two and six that he should pay two pounds and six shillings, not two shillings and sixpence. Germans landing with radios seemed not to have been informed that if they persisted in transmitting from one location the British could use direction-finding equipment to track them down. None of them could know that their faked identity papers contained easy-to-spot errors that had been deliberately inserted by Snow when the Germans had sought his advice.

From September to November 1940, the Germans landed 21 agents in Britain. All but one was either captured or surrendered. The exception committed suicide. Faced with the choice of cooperating or being hanged, a number opted for life. Wulf Schmidt was one of these. Codenamed Tate, he converted so sincerely to the Allied cause that he grew to be one of the most trusted of the double agents.

Why Didn’t the Germans Catch On?

There are several reasons why this false infrastructure of espionage endured throughout the war without the Germans ever catching on to the fact that they were being deceived.

One reason is that the job security of a German spymaster—and quite possibly his life—depended on having found, launched and guided an agent. If the agent’s reliability was questioned, his spymaster became his chief defendant.

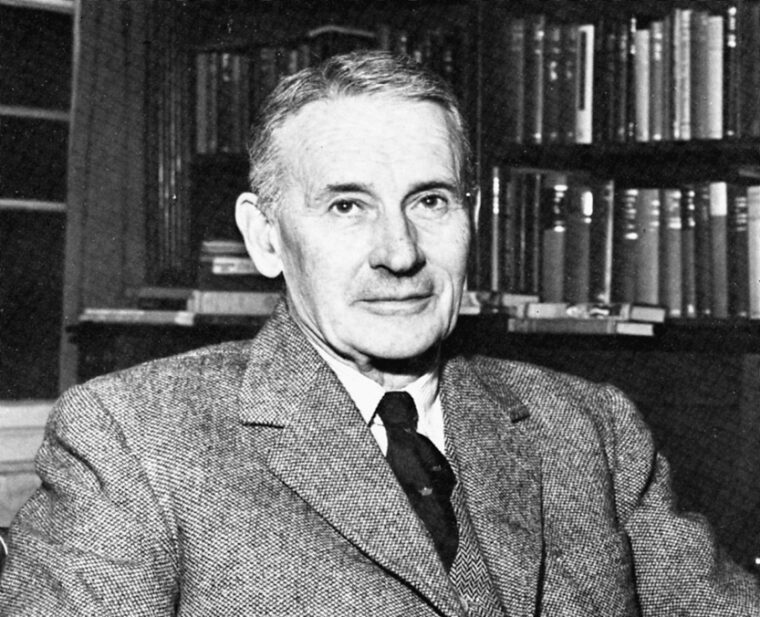

A more important reason is that the double agents were under the control of the very clever group of British, and later, American masters who made up the XX (Double Cross) Committee. The Committee was adept at concocting a steady stream of information that was seemingly of value to the Abwehr spymasters, while also including a subtle edge of misinformation. The committee was headed by J. C. Masterman, a pre-war writer of popular mystery novels who now turned his skills to the task of supervising the scripts to be transmitted to the Germans.

Meeting weekly from January 1941 to the end of the war in Europe, the committee members were careful never to release new material until it had been cleared by the appropriate authority. Many well-crafted scenarios had to be rejected by cautious reviewers. To continue creating convincing messages in the face of such obstacles posed a constant challenge to the committee’s ingenuity.

The Double Cross Committee’s Early Successes

Masterman and his mates were, at the beginning, cautious in their use of the double agents. They found it hard to believe that they had every German agent under control. When this discovery was confirmed, they realized what an invaluable asset they held in their hands. The queries that German controllers sent their agents often revealed the current thinking of German leaders. The misleading bits of information included in the spies’ reports could slowly warp enemy judgments of Allied plans and intentions. It was also clear that major deceptions could not only be initiated; the committee could, by taking note of the spymasters’ responses, determine whether or not the duperies were being believed. The committee recognized that its first need was to build the agents’ credibility with their spymasters. They sought to mislead the Germans only in minor ways.

For example, when invasion of Britain was threatened, the agents exaggerated Britain’s readiness for defense. Shore defenses were described as being stronger and RAF Spitfire fighter planes more numerous than they were in reality. The production of planes being turned out by British factories was inflated.

The Committee took elaborate care to assure that the agents’ reports were verifiable. If a German controller sought details of a particular British factory, the agent was taken there to see the facility for himself. When Zigzag was given orders to bomb the De Havilland aircraft factory, camouflage experts created a fake extension that was blown up without affecting actual production. Similar assignments were carried out against a simulated food storage facility and a mock generating station. When newspaper reporters played up this succession of disasters, their accounts made good reading to be passed on to spymasters.

A somewhat more important task for the double agents came when the Allies were planning their landings in North Africa. The Axis powers were aware that the Allies were plotting a major operation, but they were uncertain what it would be or where it might fall. Decrypts by Allied codebreakers revealed the Germans’ conviction that if the Allies were planning an invasion of the North African coast they lacked the shipping to manage landings inside the Mediterranean.

Messages from the double agents played to these uncertainties. They raised the specters of an attack through Norway or landings in Northern France. They emphasized the shortage of shipping. The deception worked. There was little opposition when the Allies did move into the Mediterranean and make landings at Oran, Algiers along with the city of Casablanca on the Atlantic coast.

Preparing for D-Day

These preliminary deceits were rehearsals for a larger role. As Masterman expressed it in his postwar account: “At some time in the distant future a great day would come when our agents would be used for a grand and final deception of the enemy.”

That day arrived with the planning of the Normandy landings. By then, the most inventive of the agents had gone well beyond merely submitting solo reports. They had followed Garbo’s example and had created networks of fictitious sub-agents who filed their reports from all over Britain. Garbo set the pace by employing no fewer than 24 imaginary helpers. Each had his or her own persona and writing style. Collected after the war, the reports penned by Garbo for his diverse cast of characters filled some 50 volumes.

One of Garbo’s sub-agents, reporting from Liverpool, came to be seen as a problem. When German aircraft forced the closing of the Thames as a convoy destination, Liverpool became the main convoy harbor. An agent there could be expected to see more than the Allies wanted him to report. Garbo’s solution was simply to have him succumb to a malevolent disease. When the agent’s faked obituary was published, Garbo sent a copy to his spymaster, who returned a message of condolence for the bereaved widow.

Operation Fortitude

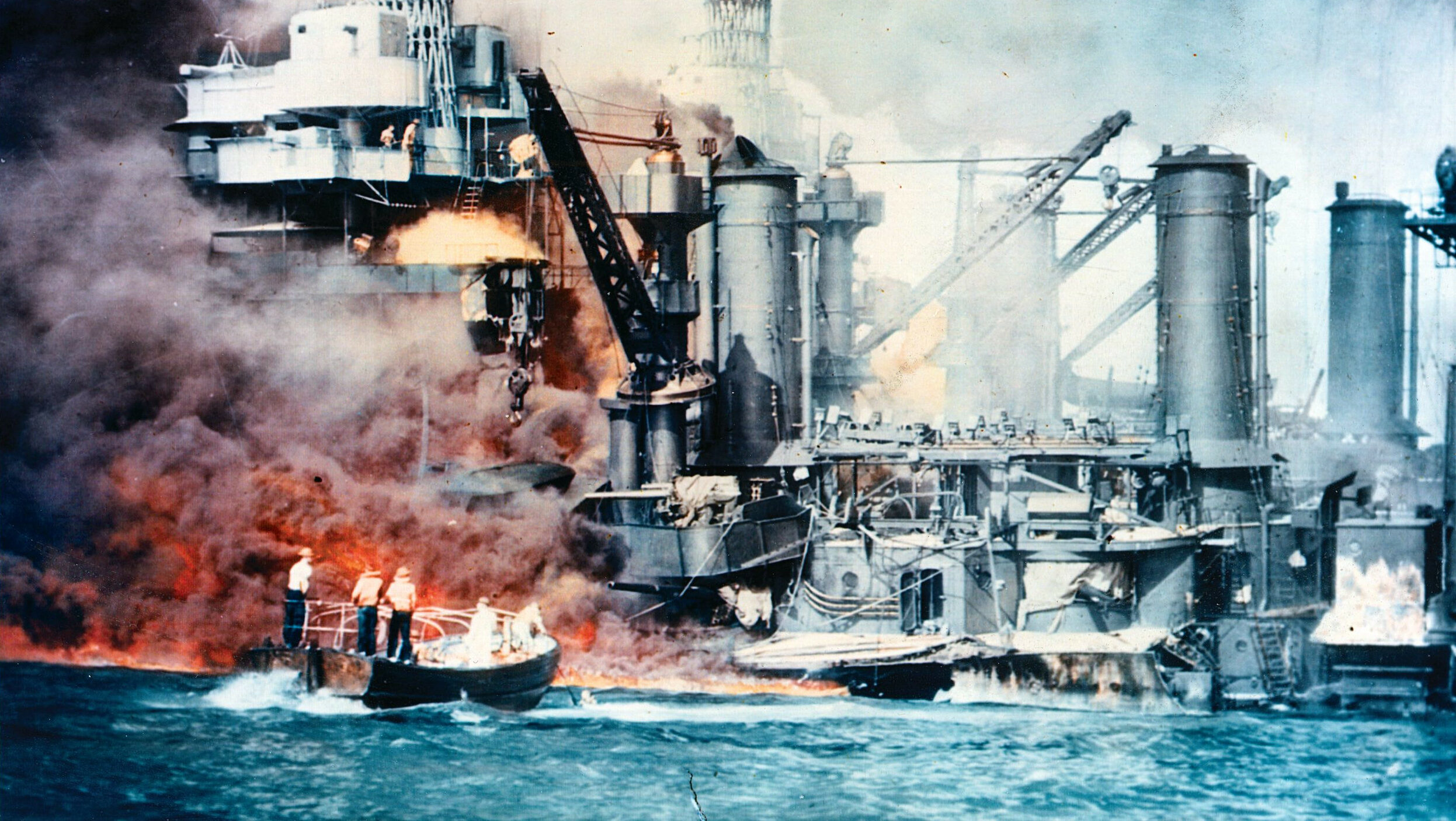

The time then came to launch Operation Fortitude, the D-Day deception. Allied codebreakers had determined that the Germans expected the invasion to fall on the Pas de Calais, where the English Channel was at its narrowest and the path toward Berlin the most direct. That was where the German generals would have landed if the tables had been turned. Fortitude played to this expectation by creating a largely fictitious force, the First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG), biding its time in southeast England opposite Calais. FUSAG was flamboyantly commanded by the general the Germans most respected and feared, George S. Patton, Jr.

The tasks given the double agents were several. One was to strengthen the Germans’ belief that FUSAG would invade the Pas de Calais. Another was to assure them they must stand ready to repel other landings anywhere from the Scandinavian peninsula to the west coast of France. Still, a third was to lull them into believing the date for the landings would be later in the summer than was actually planned. Lastly, the Germans must be convinced that the Normandy invasion was only a feint meant to divert their attention from the main attack by the army under Patton.

As D-Day approached, the double agents brilliantly carried out their assignments. The messages detailing FUSAG spurred Hitler to assign the Fifteenth Army to the Pas de Calais. Tricycle traveled to Lisbon to personally deliver to his controller the complete order of battle of the notional FUSAG. Tate made a new friend, a gabby (and imagined) railway clerk in Kent who kept him informed on the rail arrangements for marshaling FUSAG troops at their embarkation points. Brutus got himself assigned to Patton’s headquarters and kept his spymaster up to date on changes in the group’s order of battle. After the war, German General Alfred Jodl recalled that 15 divisions had been held at the ready to turn back the invaders who never came.

The agents working to keep the Germans worried about other possible landing sites were equally as effective. In Scotland, the agents codenamed Mutt and Jeff reported on the build-up of the Fourth Army, which the Germans believed to be an expeditionary force of 250,000 men ready to land in Norway. In actuality, this “army” consisted of 28 overage officers, 334 enlisted men and a team of radio operators using a British invention that enabled one operator to simulate the traffic of entire networks. This deceit held 250,000 German troops in Scandinavia when 100,000 could have handled the occupation duties.

Similarly, a female agent codenamed Bronx convinced her controller that, after the first Allied attacks, a follow-up landing would be made in the Bay of Biscay on the west coast of France. As the result of her message, the German high command ordered a Panzer division to remain in the Bordeaux region rather than hurry northward to help repel the Normandy invaders. Also, in the Middle East, the threat by another largely imaginary army to launch an attack through Crete and Greece compelled the Germans to shift additional troops to the Balkans.

As for the timing of the landings, the efforts of the double agents, combined with the foul weather at the beginning of June, persuaded the Nazi leaders that nothing was imminent. On D-Day, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, commander of the Atlantic Wall defenses, had gone home to celebrate his wife’s birthday, while several other generals were away from their posts to participate in a war game.

Fortitude’s Coup de Gras

It was left to Garbo to put the finishing touches on the grand deception. Allied command permitted him, on the night of the landings, to send a communiqué forewarning that the invasion ships were on their way across the Channel. The message would be too late to be of much benefit to the defenders, but early enough to further boost Garbo’s credibility. The consequence was that on D-Day plus one, just when the Germans had begun to move elements of the Fifteenth Army from the Pas de Calais to mount an attack against the fragile beachheads, Garbo sent this message:

“It is perfectly clear that the present attack is a large-scale attack but diversionary in character to draw the maximum of our reserves so as to be able to strike a blow somewhere else with assured success. The constant aerial bombardment which the area of the Pas de Calais has suffered and the strange disposition of these forces give reason to suggest an attack in that region of France which at the same time offers the shortest route for the final objective of their delusions—Berlin.”

The message went straight to Hitler. The dramatic result was that just when the Fifteenth Army was moving to crush the invaders, the Führer not only ordered the troops still in the Pas de Calais to stay put, but also called back those units that had already departed for Normandy.

For the spies who never were, this was their climactic moment. The double agents had fulfilled Masterman’s prophecy: their individual artifices had built into one grand deception. They had used the threat of a fabricated force to compel the Germans into misinterpreting the real meaning of Normandy. They had kept hundreds of thousands of German troops far from the embattled beaches. They had misled the enemy into believing the landings could not possibly come as soon as they did. At the moment when the invasion was most vulnerable, they had so deceived Hitler that he not only recalled his most potent force, but also continued to expect, well into July, that an attack by FUSAG was in the offing.

As Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower summed up Fortitude’s success in his report to the Combined Chiefs of Staff: “The German Fifteenth Army, which, if committed to battle in June or July, might possibly have defeated us by sheer weight of numbers, remained inoperative throughout the critical period of the campaign, and only when the breakthrough had been achieved were its infantry divisions brought west across the Seine—too late to have any effect upon the course of victory.”

Somewhat to their surprise, the double agents’ participation in Fortitude did not forfeit their masters’ belief in them. Garbo and crew continued to be of service in support of the battles on the continent. The very real probability that they had saved the invasion forces from being driven back into the sea will be remembered as their greatest contribution to Allied victory.

World War II veteran Hervie Haufler is the author of a review of World War II, in all its major theaters, from the codebreakers’ perspective. It is published by Penguin’s New American Library.

I remember when I saw stuff about this in Ohio. I do find a lot of this sceptical but at the same time I may not be remembering right.