By Peter Suciu

For collectors, finding out that an item believed to be authentic is actually a fake can feel like being punched in the stomach. Even the most advanced collectors will tell you that they have been duped over the years, and most say that they look back on it as a learning experience. That’s easy to say after time has healed the wounds, but discovering that an item is fake is never welcome news.

Why are some items of militaria so widely faked? The answer is simple: because there is money to be made. Even items that seem low cost by American standards are copied in surprisingly large numbers in eastern Europe and the Middle East. In much of the developing world, there are plenty of skilled craftsmen who can create near-perfect copies in a short amount of time, and some of these fetch high prices.

Another frequently asked question is why, with so many replicas on the market, they aren’t better marked to distinguish them from the real thing. Here, it is necessary to distinguish between what is a replica and what is a fake. The terms are often used interchangeably, but that’s neither accurate nor fair. A replica is only a fake when it is passed off as an original item to an unsuspecting party. If it is clearly bought or sold as a replica, it is just that—a replica.

Replicas go by other names, including reproductions or copies. These are sometimes used to fill holes in collections or called into service in museums when a real item isn’t available. This isn’t to say that all collectors agree that replicas are a good thing. Plenty of them take the approach that if you can’t own the real thing, you shouldn’t bother owning a copy.

Of course, for some items this is complete nonsense. It would be impossible for a museum to display any complete tanks or airplanes without doing some restoration work. Even if there were still original paint for a tank from World War II, it still wouldn’t be completely original to a particular vehicle. But is restoring a tank to look as it did in World War II anything but a restoration job? That would seem to blur the line between original and fake. After all, the paint is new. The same could be asked of vintage trucks, Jeeps, and planes. While it is possible to get a truck running with mostly original parts from the era, no one expects a vintage airplane to take flight with original parts that could be decades old.

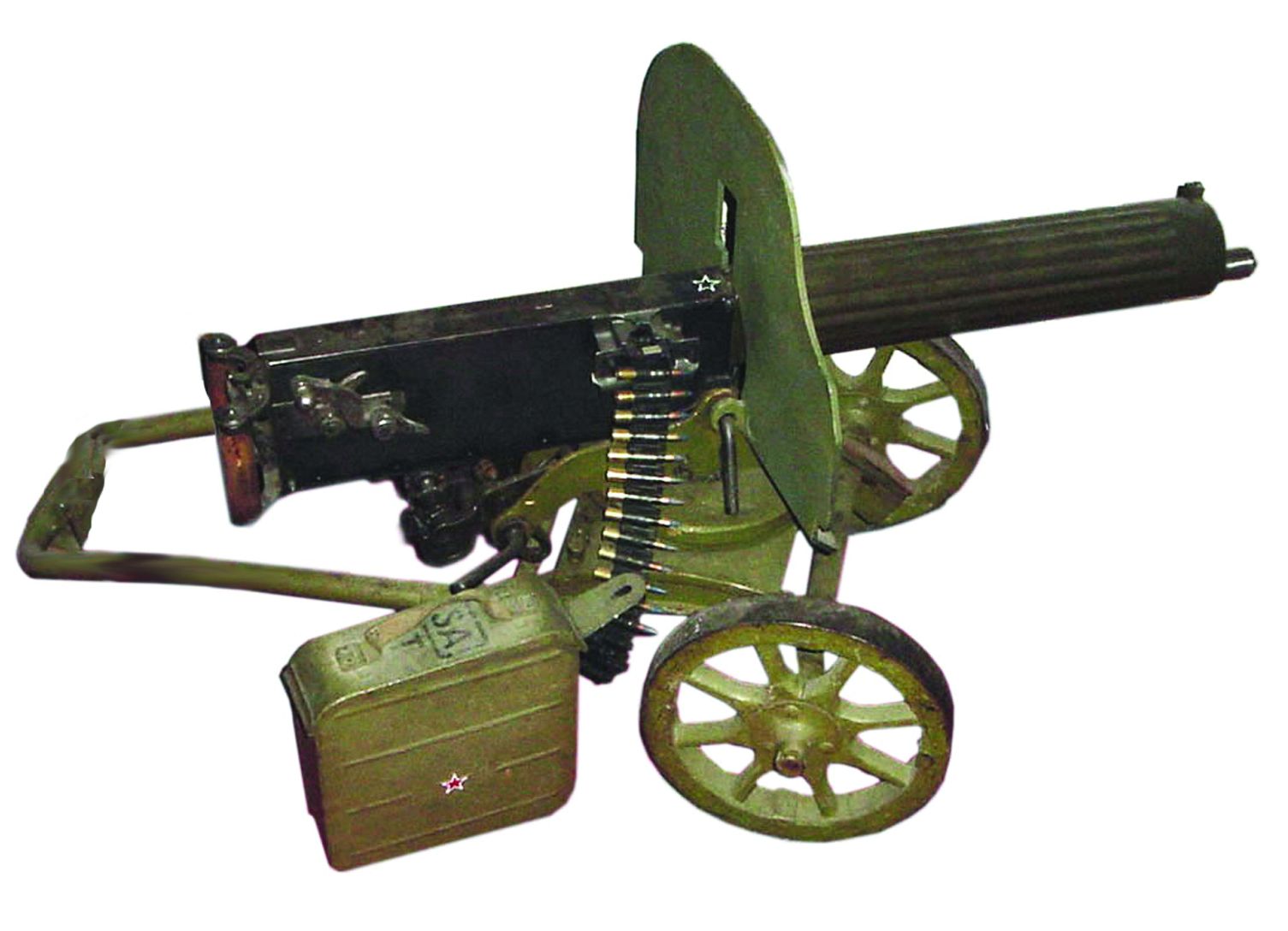

For the private collector, too, there are times when lines must be blurred. Alex Cranmer, vice president of International Military Antiques (IMA) notes that non-guns are a way to fill a hole in a collection. “For many collectors, a display gun is the only option they have,” he says. “They probably couldn’t get a license for it anyway. You really can’t tell until you go to see if the action moves. What I like to say is that we’re selling Model T Fords with solid engine blocks. That’s the difference between replica guns and a display gun. The display is 90 percent original parts.”

Some collectors can opt to go a bit further with firearms for displays, relying on modern-made display copies. These are similar to non-guns except that none of the parts are real, but from a distance they look good.

Another common misconception about reproductions is that they are essentially a new development. This is far from the truth; historical replicas date back to the Victorian era. While it is likely that there were some copies of even earlier items, it was during the Industrial Revolution that there was a sudden, new interest in the past. As a result of that interest, copies of old items, notably arms and armor, began to be made for the burgeoning English middle class. Suits of armor, helmets, shields, and other items from England’s romantic past were made, and this interest soon spread to Europe and North America.

Today, these Victorian copies are quite rare and can be very valuable in their own right. While not fetching the price of an original item from the more distant past, Victorian copies have shot upward in price over time. They also have a certain character that is often missing from today’s mail-order catalog and website versions.

More recently, many museums have looked to recreate old uniforms for display, and sometimes those can throw off even the experienced eye. “As a curator, it’s the convincing older replicas I encounter that can be daunting,” says Owen Connor, curator of uniforms and heraldry at the National Museum of the Marine Corps. “Specifically, we have numerous examples of 1950s-era Marine Corps ‘pageant’ uniforms that are quite good. With their accompanying age and craftsmanship—these often were made by uniform makers of the period and not outsourced to costume shops as we see today—it can be rather scary to determine authenticity.”

Likewise, old movie props often show up for sale as real items. From the outside, these look quite convincing, but anyone who understands the real item can easily tell the difference. To further complicate matters, many movies made before World War II used vintage uniforms and equipment, and many early postwar films also relied on actual gear. Prop houses often bought up military surplus, resulting in a mixture of movie props and real items, and today it is still possible to see prop labels on real items.

Some items that date to the actual period were simply period fakes. Two notable examples are the fake “blood chits” that pilots carried or wore to ask Chinese civilians for help if a pilot was shot down, and the “samurai” swords made by Australian troops and sold to gullible American Marines. In the former case, the fake chits seem to have originated in India, and the message was nonsensical and wasn’t actually written in Chinese. (We can only hope that no pilot was shot down while wearing one of them.) The latter items were fake Japanese naval officer swords that, while certainly made in World War II, were never wielded by Japanese officers. These are just two of dozens of types of items that were faked even before the battlefields fell silent.

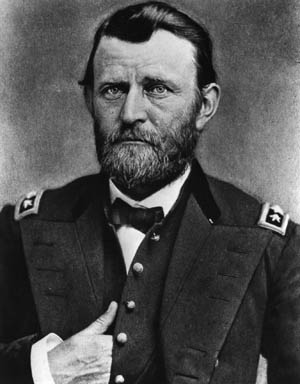

Reenacting is one facet of the collectibles hobby that is changing what people buy. Reenactors originally were happy to simply look reasonable, but today the more experienced reenactor desires to look as authentic as possible, down to the styles of bullets and fabrics that were used during a particular era. For instance, when Civil War reenactments began, a pair of light-blue United States Postal Service pants and an old blue suit jacket was considered reasonable. No longer. Today, a cottage industry reproduces everything from uniforms and helmets to personal equipment.

This dedication to realism, while great for reenactors, is somewhat disturbing to collectors and those in the museum field. “On a more interesting and intimidating front are the higher-quality repros from WWII we see at the museum,” says Owen Connor. “Many of these items from some of the better companies can be quite good.” He notes that one supplier makes an outstanding set of the WWII-issue Marine HBT (Herringbone Twill) utility uniform and claims on his website: “The Marine Corps Museum can barely tell the difference.” Needless to say, Connor doesn’t completely agree. “I was not thrilled with this and am relieved in that this comment pre-dates my time here. For the record, I bought and own this uniform out of intellectual curiosity, and I can tell the difference after lengthy weathering in Jamaica and Key West.”

It isn’t uncommon to see reenactor gear show up for sale after it’s been through a few “campaigns.” But most of the time, these still lack some of the small details that experts such as Connor can instantly note. For the collector, it is good that these newly made items are being used. “These are cheaper,” says Bernard Delgado, a former reenactor and collector of U.S. Airborne militaria. “There is no anxiety about losing or destroying them in the field.”

For those who simply look to display an item, a replica also doesn’t typically break the bank. “German World War II helmets, even in poor condition, can cost $300 to $5,000, depending on how it is marked,” says Cranmer. “We sell replicas because people might want one without spending that kind of money.” He adds that anyone who knows the real deal will know instantly that the ones sold by IMA-USA are copies.

This brings up the issue of how easily a reproduction can be passed off as an original. Many collectors ask why a replica isn’t clearly marked as such. “The problem for the collector is that we can’t stamp IMA reproduction,” says Cranmer, who adds that owners want it to appear as realistic as possible, even if it isn’t original. “That just doesn’t look right. While we don’t produce our replicas with the intention of having people sell it to collectors as real items, we do know this happens.”

And this is where the line between reproduction and fake is blurred. Sometimes reproductions are sold as originals, but now a full industry is churning out copies that are meant to deceive. “A fake is meant for that very purpose, to deceive,” says Jareth Holub, owner of Ceramic Restorations, an expert in art restoration and an advanced collector of Japanese militaria. He knows how easy it is to add age to an item, and he says greed is a prime motivator. Holub warns that, as replicas get better, they have the chance of someday being passed off as original. “Reproductions of certain items are getting much better,” he cautions. “The makers of some items are paying close attention to the details.”

To this end, collectors and dealers such as Cranmer and Holub suggest that prospective consumers educate themselves. There are plenty of published books, as well as Internet forums and websites that can help the less experienced collector, and many recommend that you buy only from reputable dealers. One easy-to-follow tip is to invest in tools such as a black light, which can help a user know if the item is period—modern synthetic fibers will glow. At the same time, collectors should heed the advice to see real items in collections. Time treats items differently than artificial means to make something look old.

Another problem with all these items is that quite often buyers are intrigued by the possibility of not only what an item is but where it came from. This is why many dealers and collectors suggest, “Buy the item, not the story.” The knowledgeable collector should appreciate not only the individual item but the history of where it was used, even if it isn’t possible to tie a particular piece to an actual individual. The best advice is to be part of a like-minded community whenever possible, to get opinions on what you collect, to share information (hoping it isn’t shared with fakers), and finally to enjoy what you collect. In the end, keeping the hobby fun is the most important part of any collector’s experience. And that’s something that can’t be faked.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments