By Coley Cowan

Friedland was burning. The darkening sky of late afternoon on June 14, 1807, was deepened further by the ashes swirling in the narrow streets. Houses collapsed, burning those who sought shelter inside. Artillery fire added to the macabre scene, a growing crescendo of sound and fury.

The Russian Army was in grave peril. General Count Levin Bennigsen, its commander, had to try to stem the growing crisis. The French advance threatened to trap his men and cut off their retreat to the relative safety of the right bank of the Alle River. He still had a strong reserve made up of the finest troops in Russia. The soldiers of the Tsar’s Imperial Guard, dressed in their tall caps, were the darlings of St. Petersburg. Perhaps they could redress the balance. The French, deep in Poland, would have difficulty retreating from their advanced position. The Russians had rattled the French at Eylau four months ear- lier amid swirling snow, which had boosted the Russians’ confidence. Perhaps the Russians could swing the tide of battle in their favor despite the late hour of the day. The Russian troops advanced in serried ranks with red flames flickering on their bayonets. The French troops met them with cold steel. This last clash of the day would decide whether the Russian Army would survive what seemed to be its imminent destruction.

Napoleon’s latest campaign had its antecedents in the War of the Third Coalition of 1805-1806. Austria, Russia, and various minor powers had joined Great Britain in making war on the newly created French Empire. Napoleon had thoroughly trounced those two powers in the Ulm-Austerlitz campaign in which he accepted the Austrian surrender at Ulm. Afterward, Napoleon crushed Tsar Alexander’s Russian army at Austerlitz. Austrian Emperor Francis II was forced to make peace, and the Russians withdrew to their homeland.

Prussia had done little in support of the Third Coalition. Prussian territory had been violated by French troops, and they were preparing to issue an ultimatum when Austerlitz was fought. The diplomats soon changed their tune and agreed to a treaty of friendship with the French emperor. The Prussians believed that they would receive Hanover, which had been owned by Great Britain, in return for their neutrality. Their troops occupied it in early 1806.

However, during negotiations with Great Britain, Napoleon offered to return Hanover to the English in return for peace. This brusque, casual, and rather humiliating treatment created a furor in Prussia. A war party quickly called for action against Napoleon. A few nobles went so far as to sharpen their swords on the steps of the palace in Berlin to show their readi- ness to take on the “Corsican ogre.”

In August 1806, Prussia began to mobilize. Russia had never made peace with Napoleon. Still smarting from the humilia- tion of Austerlitz, the Russians agreed to join in the campaign againstNapoleon. ThePrussiansweresupremelyconfidentin their own military prowess. They began the campaign on their own, attacking without waiting for Russian support; after all, they were the heirs of Frederick the Great. Victory was a foregone conclusion, or so they thought. Unfortunately, there was a new master of warfare on the European continent. During the four years of peace on the Continent leading up to the War of the Third Coalition, Napoleon had organized and drilled his troops to a degree of perfection they had not known before. They became skilled in the use of line, column, square, and skirmishing. Additionally, they had learned how to form into a “mixed order” whereby two or more companies or battalions deployed in a combination of line and column formations at the same time. These were complicated maneuvers, and they would make a difference against less trained foes.

Napoleon also took steps to improve the French cavalry, and he expanded and standardized the French artillery. He established the corps d’armee, a combined arms force of infantry, cavalry, and artillery. This force, which ranged from 25,000 to 35,000 men, could march on its own and delay a larger force until help arrived. When multiple corps concentrated for battle, they could take on the enemy’s main army or destroy a smaller force. Moving along separate roads, they could confuse and ensnare a foe, bringing on battle before an enemy really knew what was happening.

Napoleon used this new tool against the Prussians to good effect. His counterblow came much sooner than the Prussians expected. On October 9, 1806, a Fourth Coalition replaced the previous one, and Prussia and Russia quickly mobilized for a new campaign against the French. The French Army’s new corps system showed its power on October 14, 1806, as Napoleon concentrated to destroy a Prussian force at Jena. Meanwhile, Marshal Louis Nicholas Davout, with only a single corps, defeated the Prussian main army at Auerstadt the same day. The French occupied the Prussian capital shortly afterward. The Prussian Army disintegrated and subsequently surrendered in large numbers to the French. Even the aging Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blucher, a vociferous enemy of the French, was forced to lay down his arms at Lubeck on November 7. A single Prussian corps escaped the disaster and joined the Russians in Poland. But trouble was brewing for the French.

Poland proved an inhospitable area in which to campaign. The rapid onset of inclement weather turned the region’s roads into muddy quagmires that slowed French movement. As if this were not bad enough, Napoleon faced great difficulties keeping his troops supplied. The Grand Armee had always lived off the land. In the rich agricultural areas of Germany and northern Italy, this had been a relatively easy undertaking, but in the sparsely populated regions of Poland it quickly became a nightmare.

The French troops soon became sullen and in some cases nearly mutinous. Hundreds of stragglers and marauders clogged the rear areas of the Grande Armee. There were few shouts of “Vive l’Empereur.” The hungry soldiers instead grumbled and cursed. “Where is our bread,” they said whenever Napoleon rode past them.

Napoleon did try to block the retreat of his Russian enemies and force them into battle on his terms, but the deteriorating weather slowed the French as they maneuvered against the Russians. The Russians escaped the intended traps and withdrew without disaster. The French did manage to stagger into Warsaw on November 28, 1806, but after yet more indecisive maneuvering Napoleon was finally forced to face reality. He ordered his troops into winter quarters to rest and reorganize. The campaign resumed briefly in January and February 1807; however, the outcome did not alter the strategic balance.

Sexagenarian Count Levin Bennigsen led the Russian Army in the field. The Russian com- mander decided to maneuver to crush an isolated French corps under Marshal Michel Ney. But while doing so, he marched across Napoleon’s front and exposed his own flank. Napoleon was not likely to miss this opportunity, even if he was in winter quarters. The French again failed to bag the Russians as orders were lost and the troops marched too slowly in the February weather. The French wound up fighting a frontal engagement and began the main action outnumbered.

The Prussians delivered the first check to Napoleon’sunvarnishedstringofvictories. The two sides were evenly matched. In the slaughter that ensued over a two-day period, each side suffered heavy losses. Although the Russians retreated, they had fought Napoleon to a standstill. Napoleon claimed a victory, but in reality the outcome was a draw. The French did not pursue the retreating Russians, and Napoleon ordered his men back into winter quarters.

Napoleon had lost his momentum, and the vaunted Grand Armee had ground to a halt. Napoleon spent the next several months revi- talizing and refurbishing the French Army. New troops, both French and foreign, were called up, including some Polish troops. France had a long history of supporting Poland as a check to Russian expansion. When France had been distracted by the early stages of its revolution, Russia, Prussia, and Austria had pounced on Poland, carved it up, and eliminated it as a sovereign nation. Napoleon hinted at a return to the traditional French policy. The Poles might regain their independence; however, they would have to fight for it. The Poles responded, and new troops poured in. The Poles would remain some of Napoleon’s most loyal supporters throughout his rule.

Other improvements were made as well. New horses were brought in for the cavalry, artillery, and trains. These were mostly purchased or stolen from the conquered Prussians and were much stronger than the previous stock. Napoleon ordered new magazines and depots established and better rations distributed to the men. He also replenished the French frontline formations with new conscripts and troops culled from the army of Italy and scattered French garrisons. These forces were sent to guard the Grand Armee’s flanks and to monitor Austria in case the Austrians tried to make trouble while the French were distracted.

The French also cleared the city of Danzig, laying siege to and taking that port. This freed up troops for action, added a port for supplies, and simplified French lines of communication. The supply situation was much better, or at least about as good as it got in the imperial army. A new Grande Armee numbering 200,000 men was ready for campaigning by June.

For their part, the Russians had not been nearly as active as Napoleon. Tsar Alexander sent Bennigsen 10,000 reinforcements in March, which arrived at the front organized in new regiments. When campaigning resumed in June, 30,000 more Russian troops were on their way to the front but had not yet arrived. The Prussians, with most of their country occupied, were unable to furnish additional troops. At the beginning of June, Bennigsen had 115,000 men under arms. Rather than wait for the additional troops to arrive, he resolved to attack.

The Russian offensive opened on June 4. The Russians again hoped to annihilate an isolated French corps—their target was Ney. However, Bennigsen’s plan was overly complicated. He intended for six separate columns to attack simultaneously, but poor coordination forced a halt to the offensive by June 6, and the Russians began a retreat. Sensing an opportunity, Napoleon sought to envelop the Russian Army. On June 10, Napoleon ordered an attack against what he believed was the Russian rear guard at Heilsberg, but it turned out to be the main Russian force. Napoleon arrived in mid-afternoon to find Marshals Joachim Murat and Jean-de-Dieu Soult heavily committed despite his orders not to bring on a major engagement. The Russians used Heilsberg as an operational base, and for that reason it had strong fortifications. French infantry and cavalry attempted to carry Russian earthworks around their encampment. The Russians withdrew, but not without inflicting heavy casualties on the French.

At that juncture Napoleon made a serious mistake. He was torn between the objectives of Konigsberg, the main allied base, and Bennigsen’s army. He eventually resolved to pursue both objectives. Napoleon directed Murat, with a force of 60,000 men composed of Murat’s cavalry and the corps of Soult and Davout, to march against Konigsberg. Napoleon ordered Marshal Jean Lannes to the small town of Friedland, where a bridge spanned the Alle River, to watch the river crossing. Napoleon, who retained the Grande Armee reserves, positioned his force at a midway point ready to reinforce either wing. He hoped that the pressure on Konigsberg would force the Russians to battle. The French emperor’s forces were badly dispersed, though. The two wings of his army were some 50 miles apart.

Bennigsen was unable to resist the temptation offered by Lannes’s lone corps. By that time Bennigsen’s army was down to 60,000 men as a result of battle attrition and the dispatching of a large number of reinforcements to Konigsberg. Still, he attacked in the hope of wiping out Lannes’s 26,000 men before Napoleon could react. Bennigsen reached the Alle River at Friedland late in the evening of June 13 and immediately ordered his men to build pontoon bridges across the river.

The terrain around Friedland is gently rolling and open. At the time of battle the fields were planted with rye and wheat. The village was situated on the left bank of the Alle River, where it was tucked into a loop in the river. The Millstream, a tributary to the Alle, bisected the ground where the battle would be fought and also enclosed Friedland on its north side. Thus, the town was surrounded on three sides by water, to the south and east by the Alle and to the north by the Millstream.

The plains stretched west of the town for two miles before reaching a slight crest running north to south between the two small villages of Posthenen and Heinrichsdorf. A wooded tract known as the Sortlach Wood lay south of Posthenen. More woods lay to the west and north-west of Posthenen.

Lieutenant General Prince Andrei Gallitzin led the vanguard of the Russian Army across the Alle River to the west bank at 6 PM on June 13. He ordered his cavalry to attack Colonel Pierre-Edme Gauthrin’s 9th Hussar Regiment posted in the town. The Russian cavalry, supported by artillery, succeeded in driving off the French. Gallitzin’s cavalry halted near Posthenen and Hein- richsdorf, establishing a protective screen for the Russian infantry that began to arrive behind them.

Lannes also was hurrying his forces forward as rapidly as possible. By 3 AM on July 14, he had deployed upwards of 12,000 men consisting of two infantry divisions, his own cavalry corps, and General Emmanuel Grouchy’s dragoon division. Lannes sent two battalions into the Sortlach Wood to act as skirmishers in anticipation of an attack from that direction. He posted the bulk of his infantry on the ridge near Posthenen.

Skirmishing began at about 3 AM, growing in intensity as the hours passed. The Russian cavalry outposts were driven in, but the French were too weak to follow up these initial successes. About 5 AM the French tried to do so, pushing east against the squadrons of Maj. Gen. Alexei Kologribov from Posthenen.

But Lannes’s troops were badly outnumbered and in serious danger of being overwhelmed. The arrival of a division of dragoons from Marshal Edouard Mortier’s VIII Corps prevented them from being routed.

With the crisis on the French right in hand, a new one developed on the left. Lt. Gen. Fyodor Uvarov, who commanded the cavalry on the extreme Russian right flank, was pressing the Russian attack against the village of Heinrichsdorf. Contesting the advance were French dragoons and hussars commanded by General Grouchy and General Etienne Nansouty’s cuirassiers. They streamed through the fields and engaged their Russian counterparts. The weight of the French cavalry attack stabilized the French left flank. Bennigsen might have misjudged French strength. Lannes deployed a thin line of skirmishers on his front, which maintained a steady harassing fire against the enemy. He used this cover of fire and smoke, as well as the tall rye and wheat and slight irregularities in the terrain, to shift columns of troops to various sectors.

This may have led the Russians to believe they were facing a much larger force. Bennigsen was having considerable problems deploying his troops for battle. His pontoon bridges led directly into the town of Friedland so that his troops had to march through narrow streets and along the narrow strip of land beyond it before deploying for battle. Bennigsen also had noticed the problem the Millstream posed to the movement of his troops. Although not a major obstacle for his infantry, which could scramble through the steep-banked stream, the Millstream presented a major obstacle to cavalry and artillery. He therefore ordered his pioneers to construct four bridges across the Millstream to improve the link between his two wings.

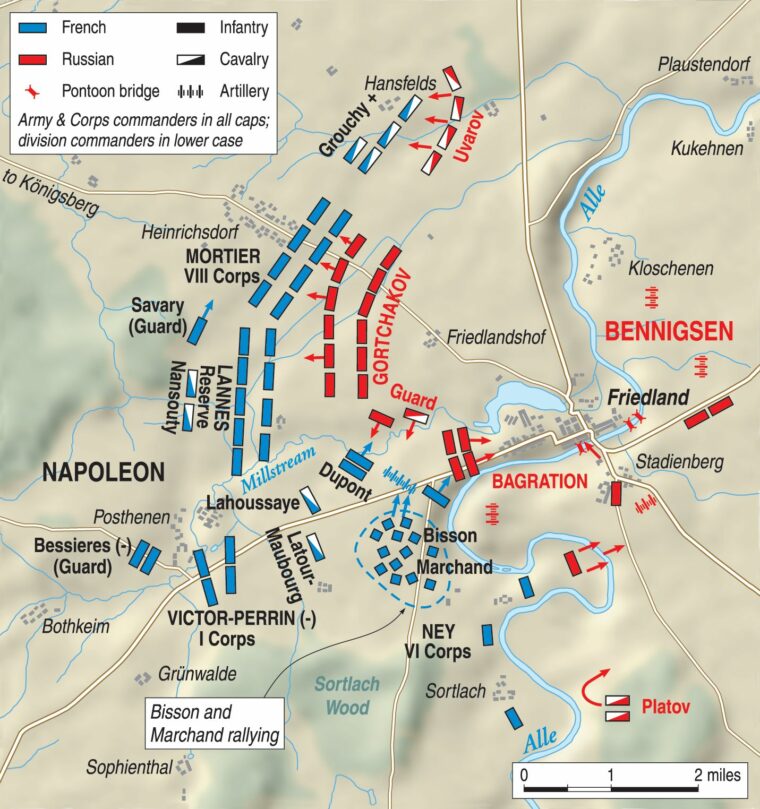

But the Millstream would continue to pose a problem despite the pontoon bridges. The stream divided Bennigsen’s army into two separate forces. Four infantry divisions under Lt. Gen. Andre Gortchakov were deployed north of the Millstream along with the bulk of the Russian cavalry under Gallitzin and Uvarov. Deployed south of the Millstream were two divisions of infantry under Lt. Gen. Peter Bagration, one of the Russian Army’s best generals, and Kologribov’s cavalry. Bennigsen eventually would have 46,000 of his approximately 60,000 troops on the left bank.

Although Lannes was in constant communication with Napoleon and knew that all available troops were moving as rapidly as possible to the battlefield, he was still heavily outnumbered. Lannes had only 9,000 infantry on hand, even though additional cavalry had raised his strength to 17,000 men.

Bennigsen ordered a general advance at midmorning. He made two main efforts. The first effort was to advance the troops of his left wing against the enemy in the Sortlach Wood. The second was on his right wing against Heinrichsdorf. Among the attacking Russian forces were elite jaegers who were specifically trained in light infantry tactics. However, the French excelled at this type of fighting. The battle swayed back and forth as light infantry on both sides fought tree-to-tree in the Sortlach Wood. By late morning, though, the greater Russian numbers began to make a difference.

The situation on the French left also was also deteriorating rapidly. Uvarov’s fearless Cossacks rode north around Grouchy’s cavalry to strike at the French left flank and rear. At the same time, Gallitzin’s heavier cavalry force engaged the French cavalry from the front. The beleaguered French cavalry on the left wing was once again in danger of being overwhelmed.

Fortunately for the French, reinforcements— General Claude Victor-Perrin’s I Corps, Marshal Mortier’s VIII Corps, and the vanguard of Marshal Ney’s VI Corps—tramped onto the field of battle. The dashing General Auguste Colbert immediately committed his chasseurs and hussars against the Russian Cossacks and cuirassiers. While the cavalry battle swirled, Mortier’s veteran infantry reached Heinrichsdorf just ahead of the Russian infantry.

Bennigsen’s attack had stalled by 10 AM. Lannes’s final division also had arrived on the field, and the French marshal was able to feed more troops into the Sortlach Wood to check Bagration’s attack. Lannes had skillfully defended his position at Friedland long enough for the French to concentrate. In so doing, he had ruined Bennigsen’s chance for a quick victory.

A lull settled over the field in the late morning as Bennigsen pondered his next move. Napoleon and his staff arrived on the field at 12 PM and took control of the battle. His arrival marked the second phase of the battle. The French emperor spent the early afternoon building up his forces and studying the terrain from a position near Posthenen through his spyglass.

Long columns of French troops continued to arrive. Napoleon ultimately would have 80,000 men, which would give the French a significant advantage in numbers. Grouchy’s cavalry anchored the left flank. To Grouchy’s right was Mortier’s VIII Corps with its left covering Heinrichsdorf. Lannes’ Reserve Corps was to the right of Mortier and situated north of Posthenen. Ney’s VI Corps held the right. Behind the French right were stationed Victor-Perrin’s I Corps and Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessieres’ Guard Corps.

Napoleon studied the terrain carefully and developed his plan based on his observations. He noted that Bennigsen’s position was a precarious one because his troops had their backs to the river and his four-mile-long battle line was bisected by the Millstream. Napoleon knew that Ben- nigsen would not be able to reinforce one wing with forces from the other wing.

The French emperor could scarcely believe his good fortune. A few of his staff officers suggested that he should postpone his attack until the next day, but the emperor knew that opportunities such as the one before him seldom came along and that he must take immediate advantage of the situation.

Napoleon decided to target the Russian forces south of the Millstream for the initial attack. Ney’s VI Corps would spearhead the attack with Victor-Perrin’s I Corps following it into battle. Their objective was to seize Friedland and the vital bridges over the Alle River. To do so, they would force the Russians back into the right angle where the Millstream joined the Alle River. Once the marshals had achieved these objectives, Lannes’s Reserve Corps would finish off the Russians that were bottled up in and around Friedland.

What Bennigsen intended to do is unclear. He could see the columns of French reinforcements arriving on the field, but he might not have known that Napoleon had assumed command. The Russian commander shortened and strengthened his line. He probably intended to withdraw his troops to the east bank of the Alle after nightfall. He needed at least five hours for such a move- ment, and it was unlikely that the aggressive Grand Armee would allow a retreat without trying to disrupt it.

But he never got the opportunity. Napoleon ordered 20 French cannons to fire several salvos in rapid succession at 5:30 PM as a signal to Ney to advance. Ney’s troops swept forward against Bagration’s corps. Initially at least, the fight on the Russian left was equally matched.

Ney’s two divisions advanced with confidence. General Baptiste Bisson’s troops advanced on the left, and General Jean-Gabriel Marchand’s troops moved forward on the right. The formations swept through the Sortlach Wood, driving the startled Russians before them.

Bagration, who was hoping to exploit the gap between the two French divisions, ordered a cavalry charge against Marchand. Lt. Gen. Aleksey Kologribov’s cavalry charged toward the gap, but General Marie Latour-Maubourg’s cavalry intercepted them, avoiding a possible disaster.

Yet a more perilous problem arose for the French. Bennigsen had placed his long-range artillery on the right bank of the Alle. He ordered his heavy guns to pour a deadly fire into Ney’s ranks. At the same time, Bagration’s field artillery blasted Ney’s forces at close range. Ney’s troops could take no more, and they recoiled in the face of the thunderous shelling.

Fortunately, Napoleon had taken steps to avert disaster. He sent General Pierre Dupont’s division of Victor-Perrin’s I Corps to support Ney’s attack, which checked the Russian cavalry. Latour-Maubourg once again ordered his cavalry to charge, and they stopped the Russians cold.

With disaster narrowly averted, Ney and others took steps to ensure their victory. Ney rallied his battered divisions and directed his artillery crews to destroy the Russian batteries across the river. The superior French artillery soon silenced the Russian guns.

At the same time, an obscure French artillery officer was doing his part to wreck the Russian Army. Thirty-eight-year-old Brig. Gen. Alexandre Senarmont had served with the revolutionary armies in northern France. He had proved himself fighting under Napoleon at Marengo in 1800 and in the Jena and Eylau campaigns of 1806.

Senarmont was the artillery commander for Victor-Perrin’s I Corps. He initially moved forward 12 guns to support Dupont’s infantry but soon realized that this was not sufficient for the task at hand. He increased the number of guns brought forward to 30, which he organized into two batteries. As they went into action, Senarmont ordered the batteries moved forward in regular intervals. The guns unlimbered 1,600 yards from the enemy but eventually advanced to within 120 yards of Bagration’s infantry.

Senarmont kept them at that distance for 25 minutes. The smoking guns poured canister fire at close range into the mass of Russian infantry in front of them. Senarmont’s guns killed or wounded upward of 4,000 Russians. In the face of such firepower, Bagration’s line melted away.

Russian cavalry tried to overrun Senarmont’s artillery by attacking its flanks, but a skillful change of front followed by a well-timed salvo repulsed the Russian cavalry. It joined Bagration’s infantry, which was streaming in disorder into Friedland just as Napoleon had intended.

The confusion on the Russian left was captured in an account by Major Reinhold von Vietinghoff, who commanded a Russian cavalry squadron south of Friedland. He went forward at 6:30 PM into the storm of French artillery fire generated by Senarmont’s guns. A staff officer ordered the regiment to which Vietinghoff’s squadron belonged to charge a French battery, but in the smoke and confusion of battle neither the officer who gave the order nor anyone else knew where the battery was situated. The Russian cavalry regiment charged anyway. Instead of attacking their objective, the cavalrymen rode down a battalion of Russian infantry. The horsemen retired to their former position, where they were exposed to the withering fire of the French guns. Fearing that the men in his squadron might flee their position, Vietinghoff placed an officer behind each file with orders to saber any trooper who tried to flee. The enemy fire was so intense that Vietinghoff felt “as if he stood before an immense bake oven.”

While Senarmont was shredding Bagration’s troops with his close-range artillery fire, Ney reformed his corps for a fresh attack. With the assistance of Dupont, Ney drove the confused Russians into the narrow peninsula between the Millstream and the Alle River where Friedland was situated.

At this point, Bennigsen ordered Gortchakov to attack the French right in the hope that it would distract Napoleon and stabilize the situation. Gortchakov hurled his divisions, which were deployed north of the Millstream, against the French left held by the troops of Lannes, Mortier, and Grouchy. Napoleon hardly seemed worried by the threat, but he did send his Guard cavalry and General Anne-Jean-Marie-Rene Savary’s brigade of fusiliers of the Guard to reinforce his left wing. The Russian counterattack had no effect whatsoever on the momentum of the attack being carried out by the French right wing. Bennigsen might have been better served trying to shift some of the forces from his right wing south across the Millstream to reinforce his crumbling left wing.

By 6:30 PM, the Russian Army was facing total disaster. The French gunners began lob- bing shells into Friedland, setting its wooden buildings afire. The fire spread to the pontoon bridges over the Alle River, rendering all but one unusable. The lack of pontoon bridges meant that many of the Russians on the left bank of the Alle would have no way to get across the river to safety.

Ney reformed his divisions in preparation for an attack into Friedland in which the French would drive the demoralized Russians into the Alle River. Bennigsen countered by ordering a bayonet attack against Ney’s right flank to no avail. Ney’s troops, which appeared unstoppable at that point, succeeded admirably in their objective, and Friedland was in French hands by 7 PM.

At that point, it was time to sweep the remaining Russian forces from the battlefield. Napoleon ordered Lannes and Mortier forward. Gortchakov’s right wing collapsed entirely. Dupont, who had led his troops across the Millstream, fell upon Gortchakov’s left flank, and Russian resistance crumbled.

One key development saved a significant number of Gortchakov’s troops. Some of his men, who were desperate to find a way across the Alle, discovered a ford near the village of Kloschenen north of Friedland. The ford was suitable both for men and limbered artillery. They established a strong rearguard, which they bolstered with artillery, and survivors streamed through the shallow water to the safety of the right bank. The French did not take many prisoners that day. The Russians chose to either die fighting or try to escape across the Alle River.

For the failed pursuit of the Russians, General Grouchy bears a large portion of the blame. He commanded 40 squadrons of cavalry on the French left flank that day. Facing him was a much weaker force of 25 Russian squadrons, some of which were Cossack cavalry of questionable value in a pitched battle.

Napoleon typically administered the coup de grace to his enemy with a great cavalry charge that smashed enemy infantry formations; however, Grouchy failed to launch such a charge.

The reasons for his failure are unclear. He claimed he had no orders, even though Napoleon had issued succinct orders. “General Grouchy’s dragoons … will maneuver so as to inflict the greatest possible harm on the enemy when he feels the necessity to retreat,” wrote Napoleon.

In addition to Napoleon, who had crafted a masterful plan upon arriving on the battlefield at midday, several of the French commanders contributed substantially to the victory.

Lannes conducted a superb delaying action waiting for the French forces to converge on Friedland. Dupont had done an exemplary job supporting Ney, and he also had shown great initiative in pressing the attack against the Russ- ian left as it retreated.

Senarmont also had a hand in the French victory. He had shown that it was possible to use artillery as an integral part of an attacking force rather than merely as support for an infantry assault. Without his timely support, Ney’s assault against the Russian left might well have failed.

After Friedland, the massed battery became a feature of Napoleon’s battles, such as Wagram in 1809 and Lutzen in 1813, but even Napoleon did not use artillery as radically as Senarmont. For his valor and ingenuity, Napoleon made Senarmont a Baron of the Empire.

The French suffered approximately 8,000 casualties. In contrast, the Russians lost 20,000 men and 80 guns. Alexander decided two days later to request an armistice. The French accepted the request on June 19. Having just won a decisive victory, Napoleon was in an excellent position to negotiate favorable terms.

“I hate England as much as you,” Alexander said at the outset of his July 7 meeting with Napoleon on a raft moored in the middle of the Niemen River. “Then peace is already made,” Napoleon replied. Napoleon and Alexander inked the first of the two agreements that became known as the Treaties of Tilsit on July 7.

Napoleon and Tsar Alexander agreed to a defensive alliance and to assist each other in negotiating peace with other antagonists. In the treaty Napoleon agreed to assist Russia in negotiating with the Turks, and Alexander returned the favor by agreeing to assist the French in negotiating with England. If the negotiations with England broke down, Tsar Alexander was willing to join Napoleon in banning British trade in his territories. One of the outcomes was that the French agreed to support Russia in its efforts to expand into Finland and the Ottoman Empire.

Tsar Alexander abandoned the Prussians to whatever fate Napoleon had in store for them. The second agreement that came out of Tilsit was the treaty between France and Prussia signed July 9. In the one-sided treaty, Napoleon took part of Prussia’s territory, forced Prussia to pay an indemnity, and limited the size of Prussia’s army. The treaty also called for the establishment of a semi-independent Polish state, the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, with the King of Saxony at its head. This rewarded the many Poles who had served with Napoleon’s army and enabled the French to establish a garrison in the duchy that served as a frontier outpost to monitor Russian military activity.

Although the Russians were able to confirm their sphere of influence in Eastern Europe, the rest of Europe was largely left to Napoleon. With Prussia humiliated and the Holy Roman Empire abolished, Napoleon reigned supreme in Germany. The French incorporated the majority of Prussia’s lost territory into the newly established Kingdom of Westphalia. Napoleon’s youngest brother Jerome was crowned King of Westphalia on July 8, 1807.

The French citizens embraced the treaty. They had grown weary of 15 years of war. The vic- tory at Friedland and the ensuing peace of Tilsit saw Napoleon at the height of his power. In the wake of the victory at Friedland, the French Empire extended from France through central Europe to the Vistula River in Poland.

Tsar Alexander was not as popular with his people when he returned to St. Petersburg. His nobles were displeased with the loss of British trade. What is more, Russian prestige throughout Europe plummeted. The Napoleonic Wars were far from over. The two great powers, France and Russia, would clash again in 1812.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments