By Simon Rees

In his father’s time, leopards had freely padded across the reception areas of the royal palace at Fez, inspiring awe and trepidation among visitors. But Sultan Moulai Hafid preferred guinea pigs in the drawing room instead. Better for health and safety, but lacking a certain regal gravitas and, for many, reflective of Morocco’s decline.

By the early 1900s, the kingdom was firmly within France’s sphere of influence. It was a prize of which French imperialists were eager to take full control. Morocco had abundant natural resources, was strategically located next to France’s immense North African empire, and had both Atlantic and Mediterranean coastlines. Importantly, it was also viewed as open to possible German encroachment, a threat that both Britain and France were keen to neutralize.

The hawkish outlook gained greater traction during 1907 and 1908 when a bloody campaign was fought to quell an insurgency in the Chaouia region that surrounds Casablanca. Foreshadowing what was to come, French intervention was provoked by a massacre of European railwaymen and builders involved in the construction of Casablanca’s new port and quayside.

French tactics involved large mobile squares of infantry supported by North African colonial cavalry, the Spahis. Rugged and perhaps a little rough around the edges, the French infantryman and his colonial counterpart were known for their marching prowess, being able to trek across miles of unforgiving terrain and still fight with tenacity on arrival. The French also used a comparatively new gun, the 75mm, that employed an advanced hydropneumatic recoil mechanism. This ensured the gun remained in place after firing and did not require resighting. The 75mm would go on to prove its value time and again during World War I.

The Chaouia conflict was a bloody affair, with quarter rarely offered or given. The Moroccans put up a determined fight, but French firepower, repeated troop surges, and scorched-earth tactics simply overwhelmed them. For example, the French surprised an enemy army at camp near the shrine of Zaouia Sidi el Ourimi and attacked with such speed and effect that London Times correspondent Sir Reginald Rankin overheard one French officer say, “Ce n’est pas une bataille, c’est une course.” This is not a battle, it is a race.

Far to the east, in the marshlands next to Algeria, the brilliant but mercurial General Hubert Lyautey was busy extending French power across vast swaths of Moroccan territory. He established a policy known as tache d’huile, oil stain, whereby a town is taken and garrisoned to facilitate trade. It was thought that commerce would then act as a catalyst for wider pacification. In the meantime, the main task force advances to the next target, repeating the earlier process and steadily spreading an area of control across the map. It was a policy that influences counterinsurgency theories to this day.

Although flush with victory, France now had to tread with great care as any overt moves to seize full control of the kingdom could provoke a hostile German response. In a game of high-stakes realpolitik, the Kaiser’s government frequently used Morocco and Germany’s trading interests there as diplomatic leverage. France was also wary of Moulai Hafid, who had only just ascended the throne. He had deposed the previous sultan, his half-brother Abd el-Aziz, after a strange nonbattle in the southern Haouz region in August 1908. Abd el-Aziz’s army disintegrated after its cavalry made a halfhearted charge against Moulai Hafid’s forces and then fell back in disarray. Such was the speed of the collapse that there was talk of betrayal in the ranks.

Abd el-Aziz fled into French protection and announced his intention to abdicate. His disappointing reign had been mired in corruption and prolificacy, where luxury items that served no purpose had been purchased at maximum expense. For example, Abd el-Aziz admitted to Walter Harris, another London Times correspondent, that he had spent £2,000 on a gold camera and between £6,000 and £7,000 on photographic materials in one year alone. To put the purchases in context, this represents a relative value of more than $1 million at today’s prices. Incidentally, the sultan was never seen engaging in this hobby. After his defeat, the deposed sultan was quickly packed off to Tangiers for a life of luxury retirement.

In contrast, Moulai Hafid was intelligent and a recognized Islamic scholar, although astute commentators noted his self-indulgent nature and a barely concealed hunger for power. Harris also repeated the rumor that he was a drug addict. The new sultan was initially backed by the religious leadership of Morocco’s principal city, Fez. He also was supported by other influential Islamic groups, including Muhammad al-Kattani and his artisan followers. In Morocco, the sultan was and is the religious figurehead, directly descended from the Prophet Mohammed’s line. He is the “Commander of the Faithful” and “His Imperial Sharifian Majesty.”

Moulai Hafid initially bolstered his popularity by trumpeting an anti-French message entwined with the rhetoric of jihad and reform. But in private, even before securing the throne, he had sent out peace feelers. The sultan believed negotiations and Moroccan reparations for the Chaouia campaign would lead to a French military exit. “When France considers her just claims have been satisfied, no doubt she will withdraw her troops,” he told a London Daily Express reporter in the early days of his reign.

Unfortunately, Moulai Hafid’s diplomatic skills left a lot to be desired. He brought advanced talks with the French Minister Eugéne Regnault to a juddering halt by demanding the French Army not only quit the Chaouia but also Casablanca. The French refused point blank and announced that future loans would be withheld unless Moulai Hafid backed down. The sultan beat a hasty retreat while asking to borrow more money in the process. Writing in 1936, former British Vice Admiral Cecil V. Usborne wryly noted that Moulai Hafid “was already beginning to place around his neck the very noose which had strangled his brother [Abd el-Aziz].”

Many of Moulai Hafid’s financial troubles stemmed from the fact that being the sultan was such a costly business: palaces, patronage, menageries, and harems all add up. In the past, sultans in need of instant cash could always raise an army and plunder the lands of a rebellious clan. The soldiers, the askars, would take a portion of the loot, but the lion’s share went to the sultan. This wild Sharifian anabasis was called a harka. But annoyingly for Moulai Hafid, it was no longer a viable option; a harka would have brought instant censure from France, his primary paymaster and creditor, and possibly afford the French a new excuse to seize yet more of the sultan’s power and territory.

Other longer term revenue streams were being eroded as domestic merchants and artisans were easily outcompeted by Western goods flooding into the country. Morocco was unable to alleviate the vast trade deficit created by increasing its export levels; the preindustrial country had little to offer the wider world other than Moorish luxury items, such as carpets or fine leatherwork. Worse still, the tariffs and customs fees made on the foreign goods entering Morocco were not as great as they should have been. Abd el-Aziz had sold around 60 percent of these rights to French banks and businesses in return for loans that had created much of the unserviceable debt in the first place. In desperation, Moulai Hafid resorted to imposing additional taxes, an action that made him increasingly unpopular.

In August 1909, the sultan finally appeared to have a stroke of good fortune. His army and its accompanying French instructors had captured Bou Hamara, a pretender to the throne and a major thorn in Morocco’s side since the early 1900s. Bou Hamara had carved out his own fiefdom near the Spanish port of Melilla, in the Rif coastal region, a place where blackmail, ransom, and cutthroat deals were the order of the day. The people of Fez celebrated this latest news with wild abandon, perhaps believing that the nation’s luck was slowly turning.

Moulai Hafid decided to have the pretender executed in mid-September after his inquisitors failed to extract the details of where Bou Hamara had hidden his ill-gotten gains. The traitor was duly placed in a lions’ den, but the well-fed beasts decided to only maul their unwelcome guest. Palace attendants were ordered to drag the pretender out and finish the job. Bou Hamara frequently treated his prisoners with equally sickening brutality and, perhaps, was deserving of little pity. However, Moulai Hafid then had the pretender’s corpse burned, an act that shocked many Moroccans as cremation breaks strict Islamic taboos.

Later that month, and possibly emboldened by the recent success, the sultan declared that he would only deal with the Western powers through their representatives in Tangiers. In response, France ceased offering Moulai Hafid military assistance. This was potentially disastrous for the sultan as he relied on French instructors to ensure his Sharifian army maintained at least a basic level of fighting efficiency. For good measure, France also threatened to seize Moulai Hafid’s remaining Moroccan customs and excise duties. The sultan backed down and, as before, asked to borrow more money.

By 1910, he was drowning in debt and took to extorting some of the kingdom’s most notable families. The nadir was reached when he ordered the arrest of Ibn-Aissa, the caid of Meknes, and members of his family on trumped-up treason charges. Moulai Hafid wanted payment in return for freedom, believing that Ibn-Aissa was wealthy enough to cover the cost. Again the sultan’s inquisitors went to work and, once again, failed in their in task. The money was simply not there. Moulai Hafid refused to believe this and changed tact, having one of Ibn-Aissa’s wives horrifically tortured until European correspondents reported the story to an outraged international audience. The French quickly pressured the sultan into recanting his actions and releasing his captives.

Moulai Hafid had also decided to sell the final 40 percent stake in customs duties and other local taxes for 90 million francs, most of which was promptly frittered away. He subsequently scrambled to cover his costs by raising the tax rates to near exorbitant levels. In the hinterlands of Fez, the important Cherarda clan started to run out of patience, and many of the other clans were not far behind. In January 1911, at Kasba Tadla, roughly equidistant between Marrakesh and Fez, major disturbances erupted. A French column sent to restore order was ambushed, with one officer and six men killed. It was a small taste of things to come. In response, the sultan decided to make an example of the Cherarda and bring them to order. No doubt he also hoped to plunder some loot in the process.

The French raised no objections. In fact, they seemed markedly keen for the harka to begin. It is believed a conspiracy had been cooked up between the French Consul Henri-François Gaillard and Charles Mangin, the head of the French military mission in Fez. They wanted the sultan’s forces outside the city to make it a more attractive target for other rebellious clans. Once Fez was threatened, the sultan would undoubtedly seek French military assistance and, in order to secure this, would be willing to give up yet more sovereignty.

Whether a conspiracy truly existed is open to conjecture; nevertheless, the French were extremely swift to benefit once the inevitable occurred.

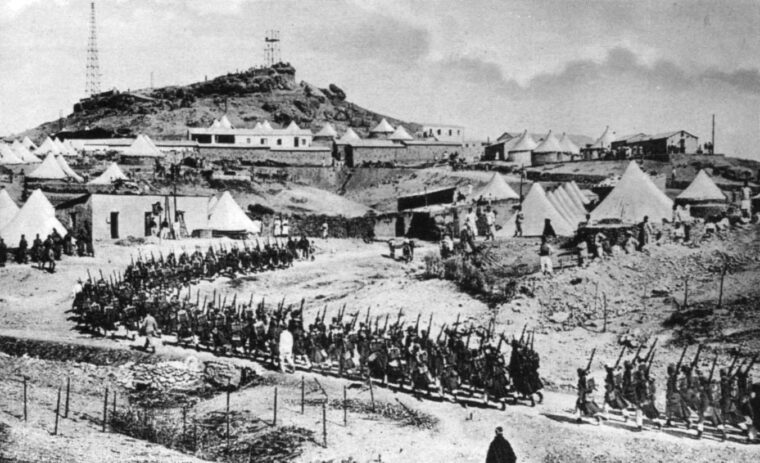

Minus the sultan, who remained entrenched in his palace, the Sharifian army marched out of Fez on February 28, 1911. The askars managed to keep formation, which the French instructors considered a notable achievement as the sultan’s soldiers could hardly be called professionals. Their pay was terrible, their terms and conditions foul. Many were forcibly conscripted. In contrast, the rebel clans were well equipped and highly motivated. Almost all were excellent horsemen, and their weapons included Winchester and Martini rifles, along with knobkerries, swords, and daggers. Movement was hampered by the early March rains that turned the countryside into a quagmire. The Sharifian army’s advance soon ground to a halt, with the soaked men facing constant harassment and dependent on their artillery to help hold the line.

Back in Fez, news quickly filtered through that several other clans had joined the revolt. On March 12, the Beni M’tir clan raided south of Fez; on March 22, the Ait Youssi joined in, plundering and looting their way almost up to the walls of Fez. By early April the clans had sounded out Abd el-Aziz as to whether he would be willing to return to power. He rebuffed their offer. Undaunted, they decided to support Moulai Zayn, the half-brother of Moulai Hafid, who was already backed by the city of Meknes’ religious leadership. By April 12, the Ouled Djama clan had occupied hills immediately north of Fez, and Gaillard began pressing Moulai Hafid to request French assistance and intervention. In the meantime, the sultan had ordered his forces to return and reinforce the capital, which they succeeded in doing by April 26. The askars’ morale was now at rock bottom, and their faith in the sultan shaky at best.

Back in Paris, the government fretted about the best course of action, fearing that overwhelming military response might rattle Germany’s cage. After a flurry of paperwork, the politicians agreed on April 23 to increase French numbers in the Chaouia to 22,000 men. Already in the field, General Charles Moinier was ordered to assemble his forces for an advance on Kenitra, about 30 miles north of Rabat, and prepare himself for a relief march to Fez. Moulai Hafid was again told to formally request military assistance. This was needed to deflect protestations from the anti-colonial lobby and any potential complaints from the Germans. Knowing full well that the French would use the situation to assert yet more control over him, Moulai Hafid slowly pondered his options until finally assenting on May 4.

Because of Moinier’s preparedness, it was deemed prudent to backdate the sultan’s request to April 27. It was a botched effort to make the proceedings seem less like a fait accompli. But despite this measure and several more besides, French intentions to increase their control over the sultanate were patently obvious. An editorial in the New York Times on May 1 hit the nail on the head, declaring: “[The] first object will be to rescue the few foreigners in Fez, but when that is done the Sultan of Morocco will be helplessly dependent on French arms for his safety and his life.”

With clearance granted from Paris, Moinier’s forces marched northeast from the Chaouia in three columns. The lead column comprised slightly more than 3,500 men and was commanded by Colonel Jean-Marie Brulard, a veteran of the Chaouia campaign. The middle column, which included the baggage train, was under Colonel Henri Gourand’s control and numbered 1,500 men. The rear guard also stood at 1,500 men and was led by Colonel Dalbiez.

French forces in Morocco were a polyglot mix. Soldiers from France marched or rode alongside colonial troops from West Africa, Tunisia. and Algeria. The French were equipped with machine guns, Lebel rifles, and 75mm guns. The troops were tough and disciplined, and many were veterans of fighting in Morocco.

French forces marched as planned through Rabat and reached Kenitra, where Moinier called a halt. Aside from his strike force of slightly more than 6,500 men, Moinier determined that an additional 3,000 men were needed to hold his lines of communication open. He also was forced to wait for a large volume of supplies to be slowly pushed up from Casablanca. The delay emboldened the Moroccans into making harassing strikes, targeting the supply columns at their most vulnerable point when traversing the large cork forest of Mamora. However, they met with little success as the latest French troop surge ensured there were enough soldiers to provide an unyielding protective screen.

Still, Paris was starting to become increasingly nervous at the slow pace, and orders were sent to speed up the relief force, orders that Moinier promptly set aside. Even Mangin’s messages warning of impending doom in Fez failed to hasten him. The army finally began its march on Fez on May 11, the day that around 3,000 rebels attempted to attack the capital’s western walls. The insurgents were forced back at the first lines of defense, although it was only a matter of time before a more concerted and audacious attack was made.

For the final approach, Moinier’s force was again divided into three columns. The columns had been reinforced slightly during the interim. Brulard’s vanguard now was composed of 3,700 men, Gourand’s middle column of 1,700 men, and Dalbiez’s rear guard of 1,850 men. Brulard reached Mercha Remla and waited for Gourand. Following their linkup, both columns marched to Lalla Ito, easily brushing aside rebel forces. The French bedded down until alert pickets spotted large numbers of Moroccans taking up positions in high grass to the south. Gourand later estimated that the enemy force numbered about 1,500 men. In response, the French made a preemptive strike at dawn the next day, forcing the enemy to beat a hasty retreat and leave behind 10 killed and three wounded.

Brulard led another successful surprise attack on the morning of May 15, this time scattering the opposition for good and enabling the French to leave Lalla Ito behind, although not before a garrison was detached to further secure the supply route. Moinier now decided to create two attack columns, one led by Brulard and the other by Dalbiez. Gourand would take control of the supply corridor and protect a major convoy that was scheduled to pass through Kenitra and eventually on to Fez. The vanguard under Brulard resumed its march, bumping into the sultan’s messengers over the coming days. Each dispatch painted a bleaker picture, with Moulai Hafid almost begging Moinier to make haste.

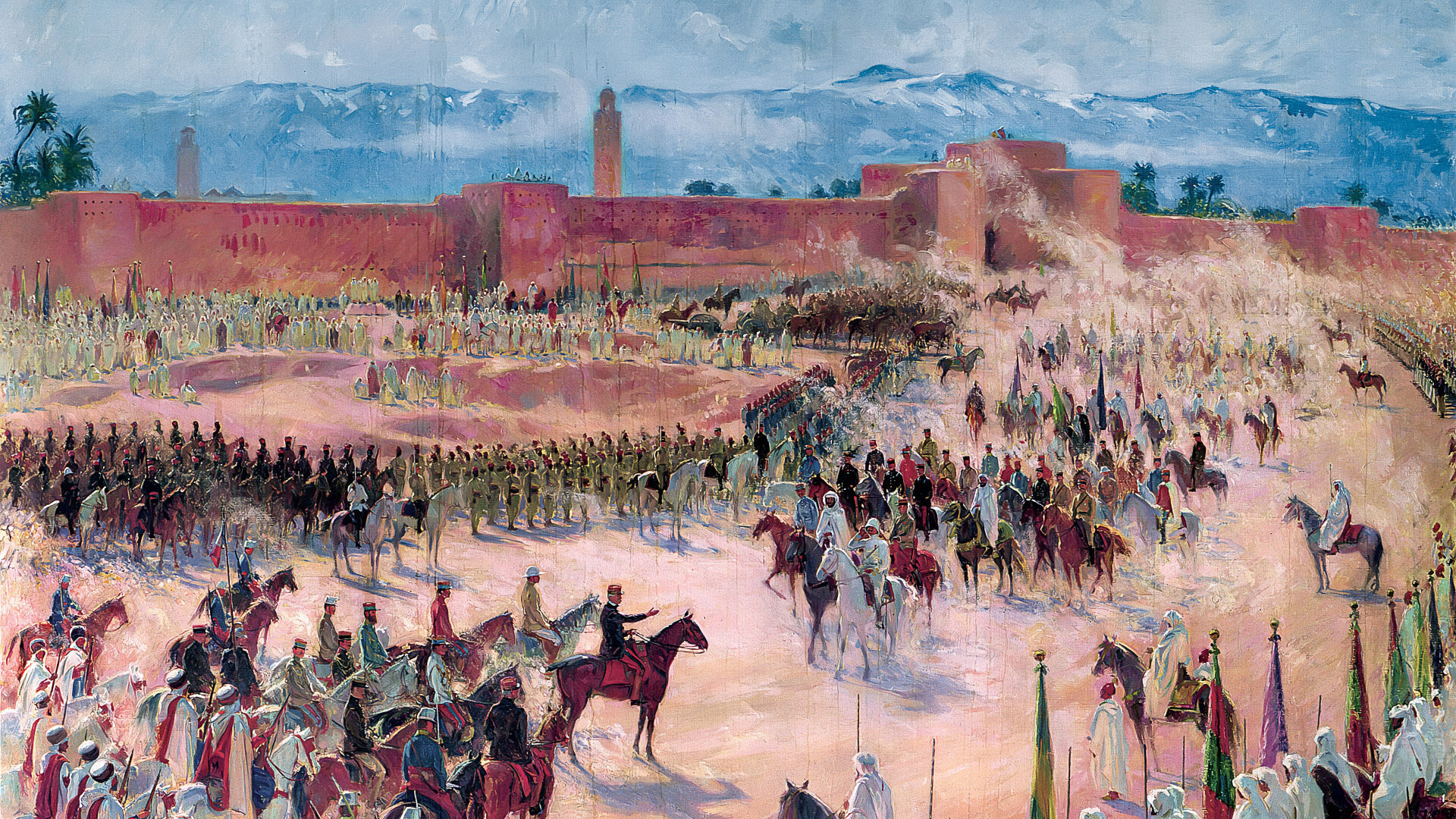

French forces finally picked up speed and, by mid-morning on May 21, were close enough to note enemy positions around Fez and observe the rebels withdrawing. The sultan could unbolt the palace gates and sleep a little easier once more. The bulk of French forces were directed to a camp on the outskirts of the city at Dar Debibagh, which was quickly transformed into a major defensive bastion.

While Moinier, Dalbiez, and Brulard were still approaching Fez, Gourand’s supply train of 1,700 fully laden camels was fending off attacks. For the clans, a target of this size and composition was akin to a miner unearthing the mother lode. On May 19, the Beni Ahsen clan attacked but was repelled for the loss of one French officer. Another assault was repulsed on May 22. On reaching Sidi Gueddar, Gourand received information that the troublesome Cherarda clan was also planning to strike. Information like this would have caused deep concern during the days of the Chaouia campaign; by 1911, the French had every reason to remain confident and press on regardless. Gourand’s column was carefully screened by its cavalry and was able to use its trusty 75mm guns to maximum effect, blazing away at the Cherarda’s attacks from both the front and rear. Reinforcements commanded by Dalbiez then arrived in support, having raced over from Fez. They alleviated the pressure and assisted Gourand’s vital cargo into the city.

The French had now reached a crossroads. They had accomplished their mission to relieve Fez, but the advantage had yet to be pressed either militarily against the insurgents or politically against the sultan. On the night of June 4-5 a force of around 1,500 rebels, primarily from the Beni M’tir clan, assaulted the French at Dar Debibagh. Their efforts were easily contained, and Moinier used the attack to initiate a series of counterstrikes that proved relatively straightforward, with the Beni M’tir preferring to skirmish and harass Moinier’s advance, albeit unsuccessfully. Advancing on Meknes, the rebellion’s hub, the French blew open the city’s Aguedal gate with high explosives, an act that prompted Moulai Zayn to surrender and submit. The clans immediately followed suit. By Moroccan standards, the would-be usurper got off lightly after being placed under house arrest in one of the many royal palaces.

The reaction in France to these latest developments was mixed, with many left pondering what the German response would be. The answer came in July 1911 with the arrival of the German gunboat Panther in the southern Moroccan port of Agadir. The kaiser’s government claimed the ship had been sent to protect German trading interests from “tribal disorder.” Britain was deeply concerned by this development, worried that the Germans might secure their own slice of Morocco along a vital stretch of the North African Atlantic coast. Thankfully, cool heads prevailed and the “Agadir Crisis” was resolved through negotiation. Signed on November 4, 1911, the Treaty of Fez ceded Germany a vast chunk of territory in the French Congo that was then annexed to German Cameroon. In return, Germany recognized French rights and interests that allowed France to formally push ahead with making Morocco its protectorate.

On November 9, Moulai Hafid accepted that his kingdom would have a status comparable to Egypt’s within the British Empire. The sultan already knew that his decrepit army was to be taken over and run by the French, who had decided to turn it into a trained force of 13,000 troops and an imperial guard of 2,000. The necessary officers and noncommissioned officer instructors started arriving in Fez during the final weeks of 1911. Moinier and the bulk of his men had remained in the region of Meknes, although a strong garrison was stationed in Fez to ensure French interests were maintained and the will of France imposed.

From their perspective, the French had every reason to congratulate themselves for a job well done. However, there had been a key oversight. They failed to appreciate or counter the growing anger within Fez, particularly among the city’s elite. Moulai Hafid was a key cause of this; he had been unable to resist his old habits of corruption, graft, and selling government posts to the highest bidders. The latter issue was not unusual, except that the sultan kept demanding repeat payments, gifts, or donations for privileges and positions thought sold. Such as it was, the government of Morocco had become a Sharifian swindle, and France was seen as the backstop behind it.

In March 1912, Regnault and a diplomatic mission arrived in Fez with a preliminary draft of the treaty to be agreed between France and the sultan. Moulai Hafid now learned that all state administration, finance, justice, and defense, as well as all foreign policy matters, were to be removed from his control. The sultan would become a puppet without any real political power. Moulai Hafid protested, made some noises about abdication, and then sulked. Faced with no alternatives, he signed on March 30.

The sultan was well aware how explosive the treaty would be among his people and so decided it was prudent to leave for the safety of Rabat, asking the French to release the details after he had departed. Moulai Hafid was unaware that the French newspaper Le Matin had already secured insider information on the treaty and had published the facts before its formal announcement. Within days of Parisians mulling the news over their breakfast, Le Matin’s scoop was met with disbelief and indignation across Morocco. As Moulai Hafid had predicted, the situation was set to explode.

The touchpaper that lit the Moroccan powder keg came soon afterward and from within the ranks of the sultan’s army. Already feeling sour about being ordered to wear knapsacks, which they thought fit only for lowly porters, the askars were angry that the French were about to stop their practice of selling rations for extra cash, goods, or the services of prostitutes. In the future, the men would be served improved rations while under the watchful eyes of their French officers and NCOs. However, this added expenditure on food would not come from the French or Sharifian treasuries but from the askars’ own pay, a penny-pinching decision that was guaranteed to upset, if not enrage. In addition, the new system came into effect on April 17, a day that was to also witness a partial solar eclipse, something that also troubled the superstitious askars.

On the morning of April 17, Lieutenant-Instructor Metzinger discovered that his unit had mutinied, with around 50 of his men racing into the streets to spread rebellion to other parts of the Sharifian army and other quarters of the city. Metzinger was bundled to safety by his troops and then later helped back to the main French camp at Dar Debibagh. This was to be a familiar pattern; the mutineers often ensured their own officers were smuggled out or detained unharmed. Artillery Adjutant Pisani was held in protective custody but managed to escape to Dar Debibagh in the early hours of April 18. Before his flight, Pisani also had the presence of mind to remove firing mechanisms from the sultan’s cannons.

Some believe the leading citizens of Fez, those who had reached the end of their tether with Moulai Hafid, may have been behind the mutiny. Certainly, some of the askars believed that the mutiny had been ordered from above, with some saying that the command had come from the sultan himself. For example, Captain Fabry arrived at his unit only to be warned off by his men, with one exclaiming, “Run, Captain! By order of the sultan we are killing officers.”

Had the sultan’s opponents used his name to instigate an uprising? If so, it was a clever plan. If all went well, the mutineers and rioters would wipe out the French and depose Moulai Hafid for them. If it failed, the fingers of suspicion would be pointed first at the sultan, allowing the elites to feign surprised innocence at the whole affair. But others have wondered if the orders had indeed come from Moulai Hafid. With hindsight, this argument seems a little far fetched; if the sultan was addicted to anything, it was to French loans and the lifestyle these afforded him. Why would he bite a hand that so willingly fed?

French officers and NCOs without the loyalty of their men, or simply caught in the open, faced being hunted down and butchered. Five soldiers at the French military telegraph office put up a spirited fight that lasted two hours before they were overwhelmed. Only one escaped. At the Hôtel de France, the lady proprietor and a Spanish Franciscan tried to reason with the rioters through the doors. They were met with a hail of bullets, killing them instantly. The European guests were no doubt glad to have their sidearms that day; they retreated to the upper floors and kept the besiegers at bay until the cover of night allowed them to escape across the rooftops.

By the end of April 17, 11 officers, eight NCOs, and nine European civilians were dead. Further slaughter had taken place in the Jewish district, the mellah, which had tried to shut itself off from the mayhem unfolding outside its gates. However, the rioters and looters eventually broke through and immediately started a killing spree. Most Jews fled to the sultan’s palace, the traditional source of protection, but many were too slow and 43 murders were reported. Felix Weisgerber, a correspondent for the newspaper Le Temps, recorded the ghastly aftermath: “Shattered furniture, broken kitchen utensils among which lie the bloated and hideously mutilated bodies of men, women and children, surrounded by bands of rats … a scroll of the law, torn and soiled, remains in a pool of coagulated blood, which emits an appalling smell.”

In charge of the French garrison in Fez, the recently promoted General Brulard had been swift to respond. Dar Debibagh was secured, while a protective cordon was put in place around the diplomatic quarter, which included the Glaoui Palace, the French and British consulates, the Auvert Hospital, and the wireless station. Convalescent and wounded soldiers were initially used hold this perimeter. Access was via the southern Bab al Hadid gateway, and Brulard decided that Major Philipot should take his men from their northwesterly positions immediately outside the city and head south around the walls. They would then enter Fez and bolster the stronghold’s defenses. However, one of Philipot’s companies became pinned down by lethal enemy fire from the walls of Fez Djedid. It took several hours to extricate this unit, which later reported 35 dead and 70 wounded.

Philipot’s two other companies avoided contact and then used the steeply banked Wadi Zitoun to move waist deep in water toward Bab al Hadid. Although slow going, the wadi offered relatively good protection from the bullets speeding overhead. Philipot’s men reached the hospital and then fanned out around the perimeter, hoping to impose order in the vicinity. The dangers were still great, and one French Senegalese patrol was ambushed for the loss of nine dead and four wounded. In the meantime, as Brulard telegraphed Moinier to send urgent reinforcements from Meknes, his artillery busied itself shelling targets of opportunity, particularly in Fez Djedid.

Clearance operations continued on April 18, with rioters and mutineers slowly dispersed or captured. Those Europeans who had successfully remained in hiding now made their way to the safety of French lines. A flying column sent from Meknes then arrived at around 3 pm, having covered 65 kilometers through unfriendly territory and without stopping. Moinier reached the city on April 23, bringing with him 23 infantry companies, three squadrons of cavalry, and several artillery batteries. The uprising was now comprehensively crushed, with around 100 mutineers sentenced to death and then summarily shot in public over the following days; it created a bad impression, for many Moroccans believed these men had been forced to rebel and thought clemency should have been shown.

It was a viewpoint shared by Lyautey, who had just arrived in Morocco as France’s new resident-general. His daunting task was to pacify the country and unify French policy between the military and diplomatic wings. The resident-general reached Fez on May 24, just as the rebellious clans decided to attack the city once more. Rather awkwardly, the skirmishing began just as Lyautey attended a garden party to officially welcome him to the city. Several guests voiced concern about the sound of gunfire, and he sought to calm their fears, announcing supreme confidence in Moinier’s men.

The rebel forces were probing for soft spots in the city’s defenses, which proved a hard task as French artillery and machine guns were able to hold off these forays. Changing tactics, the rebels decided to assail the wall between Bab Ghissa in the north and Bab F’touah in the south, and an estimated 1,500 insurgents attacked en masse. Several rebel units also occupied the tombs of Merinides overlooking French positions, while others managed to infiltrate the Mosque of Bab Ghissa, firing at a French Algerian unit from behind. The sniping caused some serious casualties: 17 dead and 25 wounded. French Legionnaires rushed up in support, cleared the mosque, and then used its minaret as a machine-gun post, firing across at targets in the Merinides tombs. The attackers were finally repelled after Moinier rushed in two battalions of reinforcements from Dar Debibagh. However, fighting continued throughout the night as localized pockets of resistance were destroyed.

The French knew that Fez was still far from secure and that another rebel attack was likely. But rather than rely on the force of arms alone, Lyautey decided to launch a charm offensive. He needed to convince the Moroccans that their interests could be aligned with his and so started holding audiences with the city’s leading citizens, including many of those from the merchant community. He listened carefully to their complaints against France and the sultan. “Every day, I interview important Moors.… I restore their confidence, listen to their complaints, which I generally rectify, for they are mostly justified,” wrote Lyautey.

Lyautey also released those rebels still held in captivity. “The repressive courts martial have included, as accomplices, on the slightest pretext, honorable people who had nothing to with it,” he wrote. Finally, he organized financial payments to Fez’s religious leaders on the condition they reduce their rhetoric against France and restrain their congregations from thinking about joining the insurgency.

The rebel attack came several days later, and the fighting proved so fierce that the French were forced to push up 29 companies against the enemy, leaving only seven in reserve at Dar Debibagh. Despite the strong defense, several Moroccan units managed to enter the city, even reaching the Mosque of Moulai Idris. But the citizens of Fez remained behind locked doors and, to the attackers’ great astonishment, refused to rise up. Lyautey’s efforts to win hearts and minds had worked; there would be no citywide rebellion. French firepower now started to tell, and the larger rebel units were simply scythed down by machine-gun or artillery fire. The bruised and bloodied survivors quickly retreated out of range.

The French counterattacked on June 1, mustering a strike force comprising five battalions, several squadrons of cavalry, and numerous artillery pieces. Commanded by Gourand, the French marched toward the nearby plain of Sebou and, as they crossed the final hillcrest, were presented with a daunting site: a hornet’s nest of around 15,000 Moroccans preparing to make a grand charge. Gourand ordered his guns to unlimber and pour down a murderous fire on the enemy once they came into range. Those that made it beyond the clouds of shrapnel were then blasted apart by small arms fire. His enemy having fallen into disarray, Gourand ordered a general advance. The clan leaders desperately attempted to rally their forces for a last stand, but it was a futile endeavor; for the average rebel it was time to secure one’s camp possessions and make a swift exit. Perhaps the largest Moroccan army put into the field against the French had been obliterated within the space of a few hours.

While France would still face other obstacles and other battles, particularly in the south, Morocco was now firmly within her iron grip. As for Moulai Hafid, his time had run out. Lyautey and countless others felt it was impossible to deal with him, while Moulai Hafid himself, like Abd el-Aziz before him, was tired of being a puppet ruler. Every cloud has a silver lining, and for the sultan it was time to drive a hard bargain in return for his departure. Now in Rabat, he whiled away his time slowly preparing for a semi-official trip to France. Persistent in his noncommittal, it appeared nothing could be done to secure a formal decree of abdication. The situation was fast becoming a Moroccan constitutional crisis as the French had already declared Moulai Hafid’s younger brother, Moulai Youssef, to be his successor.

On July 30, 1912, Lyautey arrived at Rabat to bring matters to a speedy conclusion. The sultan was offered a £15,000 per year pension. This was good, Moulai Hafid concurred, but perhaps France might care to make an additional gesture of goodwill to speed his decision along? On August 11, the day set for Moulai Hafid’s departure, Lyautey decided to pay up with a one-off sum for £40,000. According to some witnesses, the final exchange of check and abdication decree took place in the rowboat taking Moulai Hafid to the ship bound for France. Such was the distrust between Lyautey and Moulai Hafid that both men held onto the ends of their respective paperwork, each refusing to let go. The impasse lasted until a wave knocked the rowboat, temporarily unbalancing the pair and delivering a welcome resolution. If true, it was a bizarre but perhaps illustrative conclusion to one of the bloodiest and, for most Moroccans, depressing periods in their kingdom’s long and proud history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments