By Jon Diamond

Vice Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, commander of the U.S. 3rd Fleet, did not want another protracted campaign like he had experienced while trying to take Munda in New Georgia. He stated, “The undue length of the Munda operation and our casualties made me wary of another slugging match, but I didn’t know how to avoid it.”

As a result, rather than assault every island occupied by Japanese forces, he decided to bypass them and allow them to “wither on the vine” while moving on to capture more essential islands. But it was a hard-learned lesson.

Early Allied victories in the Pacific War, beginning in May 1942, have been identified as campaigns that stemmed thevictorious Japanese tide of 1941-1942. First, the “strategic victory” of the U.S. Navy’s carrier air forces at the Battle of the Coral Sea during the first week of May 1942 thwarted the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) amphibious assault against Port Moresby on the southern coast of New Guinea, protecting northern Australia across the Arafura Sea.

Second was the U.S. Navy’s sinking of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s four aircraft carriers at Midway in early June 1942, which crippled future IJN initiatives on the scale mounted during the war’s initial six months.

Third, the Americans’ epic, grueling conquest of Guadalcanal in the southern Solomon Islands by land, sea, and air forces from August 7, 1942, through February 7, 1943, deterred any planned Japanese southeastward expansion into the South Pacific, which was intended to sever the sea lanes to the Antipodes.

Fourth, the initial defense by Australian military forces in New Guineaalong the Kokoda Trail and at Milne Bay in August-September 1942 prevented separate Japanese overland and amphibious assaults, respectively, aimed at seizing Port Moresby. This was followed by a combined Australian-American offensive from November 1942-January 1943, under General Douglas A. MacArthur, through the hellacious northern Papuan jungle and coast to capture the entrenched and tenaciously defended Japanese garrisons at Buna and Gona.

What has been ignored, however, is the backbreaking series of defeats that the Japanese suffered in their attempts to defend the New Georgia group of islands in the central Solomons. The toll in Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) units, naval ships, aircraft and crews was never replaced after the defeats suffered on those jungle hellholes—especially given the requirement of Imperial forces elsewhere in the Central Pacific and on New Guinea and the Asian mainland.

Additionally, the capture of Japanese airdromes on these central Solomon Islands brought the fledgling Allied air campaign closer to Rabaul on New Britain in the Bismarck Archipelago.

The Solomon chain, consisting of six major islands and many smaller ones, is more than 500 miles long. Bougainville, 300 miles to the north of Guadalcanal, is one of the most northern in the island chain as well as the largest at 130 miles long and 30 miles wide.

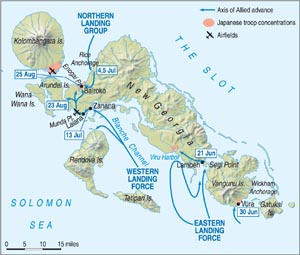

North of Guadalcanal lay the 11 main islands in the central Solomons, with New Georgia, at 45 by 35 miles, being largest. The Japanese had situated a major airfield and base at Munda Point on New Georgia’s southwestern tip. Munda Point is the approximate center of the central Solomon group and is situated about 170 miles northwest of Tulagi and Guadalcanal. Other islands in this group include Kolombangara, Arundel, Vella Lavella, Gizo, Ganongga, Tetipari, Gatukai, Vangunu, and Rendova. Rendova is located about seven miles south of New Georgia across the Blanche Channel.

The proximity of Rendova to Munda Point played a major role in Halsey’s strategic plans for his offensive after securing the Russell Islands following the Guadalcanal victory. The Russell Islands, some 125 miles southeast of New Georgia, were the obvious stepping stones for Halsey’s South Pacific Force to advance toward the central Solomons.

The terrain of New Georgia is typical of the islands in the central Solomons, with heavy rain forests covering volcanic cores. The coastline of the island is irregular with many inlets, lagoons, and channels. Immediately inland from the coast are rugged, jungle-covered cliffs; suitable landing beaches were few in number.

The Japanese reconnoitered New Georgia in October 1942 with the intent of building suitable airfields to support the action on Guadalcanal. As early as December 1942, American scout planes discovered the Japanese hard at work on a well-camouflaged airfield at Munda Point. Elements of the Sasebo 6th Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) along with some IJA detachments and construction crews had arrived in late November. American pilots also observed that another Japanese airfield was being completed at Vila on Kolombangara across the Kula Gulf from northwestern New Georgia.

By the first week of February 1943, the Guadalcanal campaign was won by the U.S. Marines, Army, and Navy after almost six months of horrific jungle combat, aerial attacks, and naval surface actions. However, the Japanese did not consider Guadalcanal’s evacuation more than a temporary setback in the South Pacific. Both the emperor and his military leaders expounded that Japanese forces were simply changing emphasis. For several months they had been on the offensive on Guadalcanal and on the defensive in Papua, New Guinea. A reversal was soon to occur.

For the IJA, after its eviction from Buna and Gona, the important matter was the capture of all of New Guinea with a renewed drive for Port Moresby from Lae in northeast New Guinea. The Solomons in the South Pacific were to be an IJN problem, under the continued leadership of the Japanese Combined Fleet Commander, Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto. This disunity in effort and planning between the Japanese armed forces had major corrosive effects in subsequent campaigns, which bore little resemblance to the lightning string of victories from December 1941 to May 1942.

Yamamoto wanted to regain the strategic initiative and win one additional major victory after the losses at Coral Sea, Midway, Papua, and Guadalcanal. A decisive Japanese victory in 1943 might compel the Allies to seek a negotiated peace and allow the Japanese to keep their new Pacific empire.

During the first week of February 1943, shortly after the successful Japanese evacuation of Guadalcanal, Operation Ke, Yamamoto drew a new defensive line in the South Pacific running north to south through the middle of the Solomons. He had withdrawn his advanced IJN bases to newly constructed airfields and installations on New Georgia, Kolombangara, and Vella Lavella in the central Solomons.

With the abandonment of Guadalcanal, Imperial headquarters in Tokyo made plans to reinforce the area to regain the initiative. The IJA and IJN would have to work together again with the latter bringing in supplies and ground reinforcements to the garrisons––especially on New Georgia with its airfield at Munda Point.

Yamamoto was responsible for continued operations in the Solomons, while Lt. Gen. Hitoshi Imamura, the 8th Area Army commander on Rabaul, directed the ground forces in the central Solomons. The IJA troops in the Solomons included the 17th Army under Lt. Gen. Harukichi (Seikichi) Hyakutake.

Following their defeat on Guadalcanal, the Japanese still retained a distinct advantage in the Solomons. Their fighter aircraft––the IJN Mitsubishi A6M Reisen, or Zero, along with the IJA Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa, or Oscar—had longer ranges (nearly 2,000 miles) than American fighter planes. Additionally, the central Solomon airfields at Munda, Vila, and Barakoma (on Vella Lavella) were to be staging areas for Japanese air raids emanating from Rabaul to attack the American bases at Tulagi and Guadalcanal.

At these central Solomon airfields, Japanese planes refueled and had emergency landing sites to conserve the diminishing number of skilled pilots, many of whom had been lost in air combat elsewhere. During the late winter of 1943, American fighters based on Guadalcanal did not have the range to reach Rabaul, engage the enemy in aerial combat, and return to their bases. Recognizing this logistical advantage, Yamamoto intended to reinvigorate his air attacks on Guadalcanal from his airdromes on Rabaul.

After Yamamoto built the central Solomon airfields, the Japanese admiral had compelled the IJA to initially provide roughly 10,000 protective garrison troops for them, including the complex at Munda Point on New Georgia.

Ironically, during a morale-boosting trip to the northern Solomons on April 18, 1943, Yamamoto’s personal IJN Mitsubishi G4M3 Betty bomber was shot down by Guadalcanal-based U.S. Army Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters. Admiral Mineichi Koga took over the Combined Fleet after Yamamoto’s death.

Between February and May 1943, the Japanese reinforced New Georgia and Kolombangara with additional IJA and SNLF troops, not knowing which was to be Halsey’s first objective in the U.S. Navy’s central Solomons campaign. In early May 1943, the commander of the 8th Area Army on Rabaul, General Hitoshi Imamura, chose Maj. Gen. Minoru (Noboru) Sasaki to lead the defense of New Georgia and Kolombangara with the designation Commanding General, Southeast Area Detachment, under the administrative direction of the IJA’s 17th Army and the IJN’s 8th Fleet situated at Rabaul.

Sasaki had three years of combat service with an emphasis on mechanized warfare. He was to command troops of the 38th Infantry Group, comprising of elements of the IJA 6th and 38th Divisions, with headquarters at Vila. By the end of May 1943, the Japanese garrison on New Georgia numbered approximately 8,000 troops. At the time of Halsey’s invasion of New Georgia in July, there would be 5,000 IJA and 5,500 SNLF troops on New Georgia, with an additional 4,200 troops available on Santa Isabel Island northeast of New Georgia and due north of the Russell Islands.

It was obvious to the Japanese high command that after the Americans secured Guadalcanal and the Russell Islands Allied fighters would be able to attack Kolombangara and New Georgia Island without much difficulty. Additionally, Munda airfield came under marauding U.S. Navy destroyer gunfire as early as March 1943. Halsey’s strategists planned for the seizure of Rendova, south of Munda Point, to serve as a staging area for the main invasion of New Georgia. Rendova was to also serve as an excellent artillery platform to shell Munda airfield with 105mm howitzers and the longer range 155mm “Long Tom” M2 cannons.

Halsey’s central Solomons offensive initially utilized the heavily reinforced U.S. 43rd Infantry Division, transported from both Guadalcanal and the Russell Islands, to secure tactical vantage points at four locales in the immediate vicinity for the eventual invasion of New Georgia and capture of Munda airfield.

The original plan for the invasion of New Georgia was prepared by Halsey’s war plans officer, Marine Brig. Gen. DeWitt Peck; however, Allied plans for offensives in the South Pacific were constantly subject to revision. Peck’s early plans called for the landing of a division-strength contingent at Segi Point on the southeastern end of New Georgia. Halsey’s ground forces would then move west in an overland trek to take Munda airfield.

Other officers had serious doubts about the feasibility of both the amphibious landing site at Segi Point and the march to assault Munda through New Georgia’s southern coastal jungle, which was dotted with Japanese outposts.

The Japanese defenders on New Georgia had speculated that the Americans would land at Dragon Peninsula on the southwestern coast and attempt a shorter overland assault on Munda airfield. Most other coastal sites had only small landing areas with thick, trackless jungle. Sasaki felt that a landing along the Dragon Peninsula would enable him to receive major reinforcements from southern Bougainville and Vila on Kolombangara to quickly bolster a defense-in-depth around Munda.

As the fractious American assault planning for New Georgia continued, an initial reconnaissance of the island was made by Marine Lieutenant William P. Coultas, an intelligence officer on Halsey’s staff, accompanied by six other Marines. This contingent landed at Segi Point on March 3, 1943. There, they met the colorful Donald Kennedy and stayed at his armed compound, which included an arsenal and a prisoner-of-war cage at the former Markham Plantation. Kennedy was a British district officer who provided oversight for the western islands and was originally stationed on Santa Isabel Island.

When the Japanese arrived on New Georgia, Kennedy escaped to Segi Point with its more central location and protected approaches with secluded coastal channels. At Segi Point he became a pivotal member of the Australian coastwatching network with expertise in radio repair and communications. Kennedy also commanded an armed local native constabulary that rescued downed Allied pilots, from aerial combat in the region.

Coultas and his fellow leathernecks spent three weeks reconnoitering the area behind enemy lines that the Americans were to soon invade and examining Kennedy’s maps at his coastwatching headquarters. Coultas had prewar experience in the Solomon Islands and spoke pidgin with Kennedy’s native scouts, who assisted his reconnaissance and evasion of Japanese patrols.

Another coastwatcher Coultas met at Segi Point was Royal Australian Navy Volunteer Reserve (RANVR) Lieutenant A.R. Evans, a prewar purser aboard a steamer in the Solomons, who would play a prominent role in the extraction of future American president Lieutenant (j.g.) John F. Kennedy and his crew after the ramming and sinking of their PT-109 by the Japanese destroyer Amagiri in Blackett Strait on August 2, 1943.

JFK’s motor torpedo vessel was attempting to interdict enemy destroyer traffic from Rabaul (the Tokyo Express), which was bringing reinforcements to Vila and Munda airfields on Kolombangara and New Georgia. In early March 1943, Evans was about to depart for Kolombangara to observe the Japanese airfield construction at Vila, which was to support the enemy airdrome at Munda Point.

After his reconnoitering was complete, Coultas reported to Halsey’s headquarters at Noumea on New Caledonia that a large-scale assault on New Georgia was still possible but not through Segi Point. Coincident with Coultas’s mission, four other Marine patrols with the aid of other coastwatchers in the central Solomon area explored the Roviana Lagoon on the Dragon Peninsula’s eastern shore and identified Zanana and Laiana Beaches as suitable amphibious landing areas. The reports of these Marine scouting patrols clearly demonstrated that Halsey’s assault on New Georgia could be made at points much closer to Munda than had previously been thought.

Halsey’s planners now called for landing separate forces at a number of sites in preparation for a major amphibious landing at Zanana beach via the Roviana Lagoon. Rendova, with its barrier islets and harbor, was to be transformed into a PT boat and forward artillery base to interdict the IJN’s seaborne supply runs and to shell Munda.

Three additional targets were deemed necessary to occupy for the eventual seizure of Munda airfield. These included Segi Point, Brig. Gen. Peck’s original main landing position, on the southeastern end of New Georgia near Donald Kennedy’s compound; Viru Harbor, a Japanese base up the southern coast of New Georgia west of Segi Point; and Wickham Anchorage, a well-situated, sheltered Japanese-occupied harbor off Vangunu Island’s eastern coast, to the east of Segi Point.

The American landing at Segi Point was launched in response to fears of a looming Japanese assault there by the entire 1st Battalion, 229th IJA Infantry Regiment. The Japanese objectives were to seize Kennedy’s fortified base and subsequently build their own airfield at Segi Point. However, Halsey’s planners wanted a fighter strip to be built there by the U.S. Navy Construction Battalions, or Seabees. An airstrip at Segi Point would minimize the distance Halsey’s planes had to fly on missions to the central Solomons from their current airfields on Guadalcanal and from newly constructed ones in the Russell Islands.

Half of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion, under Lt. Col. Michael Currin, landed at Segi Point on June 20-21, 1943, as part of Halsey’s Eastern Landing Force. Colonel Harry B. Liversedge, who oversaw the stateside training of Marine Raider battalions in September 1942, commanded the newly formed (March 1943) 1st Marine Raider Regiment, composed of the 1st and 4th Battalions.

Soldiers of the 1st Battalion, 103rd Infantry Regiment, 43rd Division along with an airfield survey party also landed at Segi Point on June 22 to assist the Marines. The Eastern Landing Force’s mission was to protect Kennedy’s base and the surrounding area for the planned American airfield from any Japanese encroachment from either Viru Harbor or Wickham Anchorage.

As no major encounter occurred at Segi Point, the detachment from the 4th Marine Raider Battalion moved west through intense rain and thick mud to attack Japanese installations at Viru Harbor from the rear on June 30, 1943. After some firefights and a failed Japanese banzai charge by 250 men of the IJA 229th Infantry Regiment, the Marine Raiders captured the enemy compound and a landing-barge facility and shore battery at Viru.

After ferreting out enemy snipers in the surrounding jungle and with the surviving Japanese retreating west to Munda over jungle trails, the Marines turned over the area to Army troops. By July 1, the Japanese position at Viru Harbor ceased being an issue for Halsey’s subsequent movements through Blanche Channel toward the Dragon Peninsula and Rendova.

Another element of Halsey’s Eastern Landing Force seized Wickham Anchorage on June 30, 1943. With its location between Vangunu and Gatukai Islands east of Segi Point, Halsey planned it as a fueling station for PT boats and other small craft moving north from Guadalcanal.

On June 30, Halsey’s Western Landing Force assaulted Rendova during intense tropical rain at that island’s North Point. Elements of the 169th Infantry Regiment, 43rd Division also seized two smaller barrier islands, Bau and Kokorana, to keep Blanche Channel’s approach to Rendova harbor open.

The 43rd Infantry Division’s 172nd Regimental Combat Team’s (RCT) 3,500 men and a battalion of the 103rd Infantry Regiment landed at Rendova and faced no more than 400 Japanese in a series of firefights. The Japanese troops were in company strength from the 3rd Battalion, 229th Infantry Regiment and the 2nd Company of the 6th Kure SNLF.

U.S. Navy destroyers accompanying the transports silenced some Japanese artillery batteries on Munda Point. Fortunately for the Americans landing on Rendova, the majority of Japanese naval guns at Munda were not properly sited to fire on the assault beaches. Also, the Japanese mountain guns at Munda did not have the range to harass the Western Landing Force’s amphibious assault. A few of the enemy on Rendova escaped to Munda.

As the soldiers of the 172nd RCT moved inland from the beachhead on July 1, the Marine 9th Defense Battalion erected anti-aircraft emplacements for their 90mm, 40mm Bofors, 20mm, and .50-caliber guns around the Rendova Plantation.

The predictable Japanese aerial counterattack, although with only Zero fighters from Rabaul, ensued that morning. Allied fighters were dispatched from Guadalcanal and protected the invasion fleet without losing a ship.

Another late afternoon Japanese air attack with both fighters and torpedo bombers disabled Admiral Turner’s command transport, the USS McCawley, which was later inadvertently sunk that night, probably by torpedoes from an American PT boat.

During the next few days, Japanese air attacks inflicted 150 casualties on Americans at the Rendova beachhead and destroyed several landing craft. Japanese cruisers and destroyers also moved through “The Slot,” the channel running between islands in the Solomons, at night to harass the beachhead; however, the success of the Rendova landings was complete. Long-range artillery was in position to shell Munda airfield, although the Marines and soldiers on Rendova had to contend with the ceaseless rain, tenacious mud, and numerous treetop-level Japanese air attacks.

Rendova was secured on July 4, 1943. Halsey’s staff anticipated that after four days on Rendova sufficient men and matériel would be concentrated for an assault across Roviana Lagoon to Zanana Beach on the southeastern side of the Dragon Peninsula on July 4-5, to commence the direct invasion of New Georgia with a large-scale force at a site closer to Munda airfield than originally planned.

General Sasaki was at Munda and observed firsthand the successful American landings at Rendova. The Japanese commander did not swiftly contest Halsey’s Rendova attack since he believed that the Americans were going to land at Lamberti Plantation or Munda Point itself.

However, on June 30, 1943, Sasaki personally observed two companies of the U.S. 169th Infantry Regiment occupying two islets, Baraulu and Sasavelle, on either side of Onaiavisi Entrance, the waterway leading from Blanche Channel into Roviana Lagoon and Zanana Beach. Sasaki concluded that Zanana Beach was where Halsey intended to land on New Georgia in strength.

Upon sighting the Americans on these islets, Sasaki ordered his outlying garrisons in eastern New Georgia to withdraw inland toward Munda, some 200 of whom were available to defend the airfield in mid-July through early August.

Halsey had placed U.S. Army Maj. Gen. John H. Hester, commander of the 43rd Infantry Division (a New England National Guard Unit), as commander of the New Georgia Occupation Force (NGOF). Hester’s mission, after moving from Rendova to Zanana Beach, was to march west to seize Munda airfield.

On July 3-5, Hester began ferrying troops over in landing craft or coastal transport vessels, Assault Purpose Destroyers (APDs) that were converted World War I destroyers, from Rendova to Zanana Beach. His landing force included major elements the 43rd Infantry Division’s 169th and 172nd Infantry Regiments, a battalion of Army field artillery, two battalions of Navy Seabees, a small detachment of the 1st Fiji Division, elements of the 9th Marine Defense Battalion, and other units of the Fleet Marine Force.

To assist isolating Munda airfield, Colonel Liversedge took 2,600 men of the 1st Marine Raider Battalion, 1st Marine Raider Regiment along with the 3rd Battalion from each of the 145th and 148th Infantry Regiments of the 37th Division to occupy Rice Anchorage on the far western coast of New Georgia along Kula Gulf opposite Kolombangara.

Although the 1st Marine Raider Regiment was originally composed of the 1st and 4th Raider Battalions, half of the 4th Raider Battalion was deployed along the south coast of New Georgia at Segi Point and Viru Harbor, while its other half was at Wickham Anchorage on the southeast coast of Vangunu Island. Liversedge’s formation was designated the Northern Landing Force.

Rice Anchorage was a swampy river delta northeast of the Japanese positions at Enogai Inlet and Bairoko Harbor. With the aid of native scouts and coastwatcher guides, approach routes to Enogai Inlet from Rice Anchorage were hacked out of the jungle.

After arriving unopposed, the Marines and soldiers were met with Japanese 140mm artillery shelling from Enogai, which scattered their naval landing force, leaving the Americans without supplies and isolated until Enogai could be taken. The capture of Enogai and the subsequent intended assault on Bairoko were to prevent the Japanese from reinforcing the Munda area through Bairoko Harbor from Vila on Kolombangara.

Liversedge’s force proceeded on an eight-mile overland march from Rice Anchorage that became a protracted three-day ordeal as the Americans had to traverse flooded jungle swamps and two rivers running high because of the torrential rainfall.

The Marines of the 1st Raider Battalion were to directly assault the Japanese garrison at Enogai on the western side of Enogai Inlet, while the two inexperienced Ohio National Guard battalions of the 37th Division were to secure the inland trails and communication routes in the vicinity.

The Japanese barge base at Enogai was defended by a garrison of 800 6th Kure SNLF troops. In addition, the enemy base had a battery of four 140mm rifled naval guns sited to command Kula Gulf; Marine patrols had recovered the detailed plans for Enogai’s defense from dead Japanese soldiers.

After five days of sporadic jungle combat between company-sized forces, the Japanese positions at Enogai collapsed on July 10, the enemy survivors either having fled to Bairoko or having attempted to swim to small islands offshore in Kula Gulf under Marine gunfire from the shoreline.

The encounter left a casualty list of 48 dead Marine Raiders and nearly a hundred other casualties as Liversedge radioed for PBY Catalina flying boats to be dispatched to extricate the wounded. The dead Marines were buried at a small, improvised cemetery at Enogai.

In addition, there were resupply and reinforcement issues for the Army units of the 3rd Battalion, 145th Regiment, which was maintaining a blocking position on the Bairoko-to-Munda trail that was established to interdict Japanese reinforcements from the airfield. Disease, lack of rations, and near continuous jungle combat had reduced the battalion’s strength of 750 men by half.

Liversedge had to eventually abandon the trail block and ordered the surviving soldiers back to Triri, farther inland, to refit and prepare for the upcoming Bairoko assault.

The 1st Raider Battalion was reinforced with elements of the re-deployed 4th Raider Battalion, under Lt. Col. Michael S. Currin, which had landed at Enogai on July 18.

The remnants of both Marine Raider battalions continued on to the main enemy position at Bairoko Harbor and assaulted it from the north on July 20. The Army units were to mount a converging attack from Triri to the east using an inland trail leading to Bairoko. Smaller Army detachments remained to cover both the Triri and Rice Anchorage bases.

The Japanese defenses at Bairoko were fortified with a battalion-sized garrison in possession of 90mm mortars and pack artillery; Marine 60mm mortars could not reduce the entrenched enemy positions. The Army units on inland trails made little headway against prepared enemy positions. Subsequently, the Raiders and Army units suffered grievously, the former accruing a 20 percent casualty rate through a lack of air support and absence of accurate artillery fire to reduce the Japanese bunkers.

Liversedge correctly feared that the enemy garrison at Bairoko would be heavily reinforced from Vila during the night of July 21. Finally, continued Japanese heavy mortar fire necessitated Liversedge’s withdrawal of the Northern Landing Force to Enogai. In the early hours of July 22, Liversedge radioed his superiors, “Request all available planes strike both sides Bairoko Harbor beginning 0900. You are covering our withdrawal.”

The Marines were dealt one of their few defeats in the South Pacific at Bairoko Harbor. The Japanese had held onto their barge base as the Northern Landing Force remained in possession of Enogai.

The Northern Landing Force’s mission to Bairoko was indeed bungled as it pitted green Army infantry battalions against a veteran enemy in horrific jungle terrain. Classic U.S. Army infantry tactics that had been taught at the war colleges fell apart when having to cross neck-deep waterways and walk in single file beneath the jungle canopy’s darkness.

Unlike other infantry combat locales, requested air strikes to neutralize Japanese machine-gun positions impervious to light infantry weaponry and near ceaseless mortar barrages failed to materialize. The enervating march of these American troops unfortunately bore a striking resemblance to those of other inexperienced U.S. Army units that had fought the Japanese at Buna in northern Papua in late 1942.

Elsewhere along the eastern coast of New Georgia’s Dragon Peninsula, General Hester’s 169th and 172nd Infantry Regiments proceeded slowly out of the Zanana beachhead as separate advances toward the Barike River. The Japanese noted that both the weather and American tactical caution made the 43rd Division’s advance a time-consuming, tedious one. By July 7, the two regiments finally reached the Barike River.

After receiving more than 3,500 fresh 13th Infantry Regiment reinforcements from Kolombangara via Bairoko, General Sasaki deployed them along with the 229th Infantry Regiment and elements of the 230th Infantry Regiment, the latter having fought on Guadalcanal, for upcoming counterattacks against the Zanana beachhead.

Sasaki had interposed elements of the 13th Infantry Regiment between the American 169th and 172nd Regiments on the southern portion of the Dragon Peninsula on the night of July 7. The Japanese struck the forward battalions of the 169th Regiment, with many American infantry companies literally falling apart amid the six hours of undisciplined gunfire and grenade throwing. After the previous night’s enemy attack, the U.S. infantry regiments waited two additional days to prepare to launch their assault across the Barike River toward Munda to the southwest.

Hester unleashed a massive artillery barrage during the predawn hours of July 9 to herald his infantry’s advance. The Japanese lines west of the Barike River were also plastered with more than 2,000 rounds of 5-inch high-explosive (HE) shells from a task force of four U.S. Navy destroyers.

As the naval fire ebbed, five U.S. Army artillery battalions opened up. The heavy bombardment buoyed the American infantrymen’s spirits; however, negligible damage was inflicted on the Japanese positions. American intelligence officers had little information as to where the enemy positions were or to what extent they were fortified. The movement of the two Army regiments, although on schedule, lacked aggressiveness, enabling the Japanese to remain in close contact with them while minimizing their exposure to the American artillery fire.

On July 10, five days after the landings at Zanana Beach, Hester’s staff had concluded that Sasaki’s forces were well entrenched in camouflaged coral and coconut log emplacements along the many hills leading to Munda. The NGOF would have to reduce these obstacles one at a time, often finding that others nearby were mutually supporting with an ample number of protected light and heavy machine guns screened by infantry in nearby rifle pits. Japanese mortars and light artillery pieces were well situated behind these defensive lines to wreak havoc on advancing American columns, and, in fact, stopped many units of the U.S. 169th Infantry Regiment in their tracks.

The colonel commanding this regiment and most of his staff were relieved of command by Hester and replaced by younger, more vigorous officers.

Hester realized that if he established a second beachhead at Laiana southwest of Zanana he could shorten his supply lines and assist his 169th Infantry Regiment’s advance considerably as it had fallen far behind the 172nd’s movement on its left flank. In fact, the 169th and 172nd Regiments were often out of contact with one another, enabling Japanese infiltrating units to harass the American supply lines and rear areas.

By the evening of July 13, the 172nd Infantry Regiment reached the Laiana area, but terrain, heat, and exhaustion compelled them to simply construct defensive positions for the night. The next day, the 43rd Division’s 3rd Battalion, 103rd Infantry Regiment landed at Laiana. In addition, tank lighters were offshore ready to disembark Marine M3 light tanks, six of which landed on July 15.

On July 17, Sasaki unleashed his bold counterattack against the American landing sites. Typical of the earlier fighting on Guadalcanal, poor Japanese inter-unit communication, thick jungle, and American defensive measures severely impeded the enemy counterattack.

Nonetheless, late on July 17, major elements of the 13th Japanese Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Satoshi Tomanari, marching from north of Munda turned the right flank of the U.S. 43rd Division, which was situated on the Barike River. The Japanese attacked the Zanana beachhead supply area and reached the American command post there, cutting the lines of communication to the 172nd Infantry Regiment to the southwest.

American artillery fire from the offshore islands of Roviana and Sasavele in Roviana Lagoon prevented the Japanese troops from organizing into their customary banzai charge. Together with a valiant defense by Marine and 172nd Infantry Regiment heavy weapons platoons, plus about 50 Army service (noncombatant) troops and artillerymen, the Japanese were prevented from overrunning Zanana beachhead.

By daylight, Tomanari was forced to halt his attack and order the regiment’s surviving troops to withdraw to Munda. The July 17 Japanese counterattack marked the last effort by Sasaki to mount an offensive against the American lines.

After the heroic beachhead defense, fresh reinforcements were needed. Maj. Gen. Robert S. Beightler brought his 145th and 148th Infantry Regiments (less their 3rd Battalions that had landed at Rice Anchorage as part of the Northern Landing Force) from Rendova to the battlefield to relieve the 172nd Infantry Regiment. As the bulk of the 169th Infantry Regiment was withdrawn to Rendova for rest and refitting, they were replaced by the 103rd and 161st Infantry Regiments from the 43rd and 25th Divisions, respectively, between July 18-22.

Due to the extremely slow American advance, Vice Admiral Halsey sent in Lt. Gen. Millard Harmon, South Pacific Ground Forces commander, to assess the situation. On July 14, Harmon ordered Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold, commanding officer of U.S. XIVth Corps (comprised of both the 37th and 43rd Divisions), to take over the NGOF in mid-July, relieving Hester, who reverted back to command of the 43rd Infantry Division.

Griswold had observed that the 43rd Division’s 169th and 172nd Regiments were a spent force and unable to take Munda by themselves. Nonetheless, by July 23, Griswold had the remaining elements of the 37th and 43rd Divisions, the latter moved to the left flank, deployed on a 4,000-yard front. Griswold had previously recommended that the U.S. 25th Infantry Division be deployed to New Georgia to reinvigorate the stalled offensive.

Utilizing Marine M3 light tanks and Army infantry in support of the armor on July 24-25, 1943, progress was made as the American force moved toward the Lambeti Plantation on the southern coast of the Dragon Peninsula and occupied the Ilangana Peninsula southwest of Laiana. Both locales were stepping stones towards the ultimate prize, Munda airfield.

In this action, Marine M3 light tanks of the 10th and 11th Defense Battalions worked alongside the Army units that had become stalled on the jungle trails on the way to Munda. On July 26-27, the Marine tanks led an assault on Bartley Ridge, just northeast of the airfield, but suicidal Japanese infantry charges and well-camouflaged enemy 47mm antitank guns managed to disable or destroy some of the Marine armor.

On July 29, Maj. Gen. John R. Hodge replaced Hester as commander of the 43rd Division after the relatively poor showing by the 169th and 172nd Infantry Regiments. On August 1, advance elements of the 43rd Division exited from the jungle with the southern end of Munda airfield visible. Four days later, Munda airfield was captured. Many of the remaining Japanese defenders had resorted to holing up in caves in the Bibilo and Kokegolo Hills.

On August 5, Griswold reported to Halsey that organized resistance in the Munda area had ceased. His 30,000 American troops started mopping up operations against the Japanese survivors. Considerable effort by Navy Seabees was required to repair the badly damaged Munda airstrip to make it operational again for Marine Vought F4U Corsair fighters within 10 days of its capture.

On July 21, 1943, elements of Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins’ 25th Infantry Division landed at Zanana Beach and moved northwest. The 25th’s trek took it through the jungle and swamp on the Munda-Bairoko trail where Collins’ infantrymen were tasked with severing the supply route and path of retreat for any of the Japanese remaining on New Georgia who were not encircled in the Munda area.

On August 9, a battalion of Collins’ 27th Infantry Regiment contacted patrols of Colonel Liversedge’s combined Army and Marine Northern Landing Force. The following day, Liversedge’s command was placed under the operational control of Collins’ division.

By the third week of August, both the 25th Division soldiers, along with the remaining Marine Raider and 37th Division Army units of Liversedge’s Northern Landing Force, began closing in on Bairoko Harbor. On August 24, Bairoko—an objective that eluded the Marine Raiders and soldiers from the 3rd Battalions of the 145th and 148th Regiments in their July 20-22 assault—fell to the Americans without combat. On August 29, the 1st Marine Raider Regiment embarked from Bairoko back to Guadalcanal.

The major ground fighting on New Georgia had ceased as General Sasaki skillfully evacuated the remainder of his Bairoko garrison across Kula Gulf to Kolombangara on the night of August 23, almost three weeks after the fall of Munda airfield.

The Japanese commander had previously hoped that with adequate reinforcements and supplies he could counterattack the Americans after establishing a new line on western New Georgia’s Kula Gulf coast from Bairoko Harbor to Sunday Inlet, the latter site bordering Hathorn Sound, the waterway that separated the Dragon Peninsula from nearby Arundel Island.

However, U.S. Navy interdiction of the Tokyo Express had made this plan implausible. On August 6, the Tokyo Express, laden with reinforcements from the Shortland Islands, was intercepted and many of the Japanese destroyer transports in the flotilla were sunk. As Sasaki was unable to receive any more reinforcements for New Georgia, he left the island for Kolombangara across Kula Gulf.

Sasaki was under a joint IJA/IJN directive dated on August 13 to hold out in the New Georgia group for as long as he could to enable Lt. Gen. Hitoshi Imamura, the 8th Area Army commander, to bolster the defenses of the northern Solomon Islands, especially Bougainville.

West of New Georgia’s Dragon Peninsula were the relatively flat and heavily jungle-clad central Solomons of Arundel and Wana Wana (also referred to as Vona Vona). These islands were directly south of Kolombangara with its Japanese airfield at Vila. Sasaki had previously wanted to use these islands as staging points to regain parts of western New Georgia following the loss of Munda airfield.

Elements of the American 37th Division, while attempting to clear parts of western New Georgia after the seizure of the Munda airfield, received artillery and small-arms fire from Baanga and Arundel Islands. Elements of the battle-scarred 43rd Infantry Division landed on Baanga Island on August 10 and secured it after 10 days of combat, with the few Japanese survivors escaping to Arundel and Kolombangara.

On August 11, Halsey ordered Griswold to move into position on Arundel Island and shell Vila airfield on Kolombangara. Arundel was separated from the west coast of New Georgia by the Hathorn Sound and Diamond Narrows waterways. The 172nd Infantry Regiment, 43rd Division invaded Arundel on August 27, opposed by a single company of the Japanese 229th Regiment that harassed the invaders principally by sniping and nocturnal infiltration to sever lines of communication.

Then, the intensity of the enemy resistance was heightened due to Sasaki’s orders to delay Halsey’s forces for as long as possible. On September 8, Sasaki sent a battalion from his 13th Infantry Regiment, under Major Kikuda, from Kolombangara to strengthen his forces on Arundel. The American advance was retarded by a series of enemy ambushes so that Japanese artillery on Arundel was able to shell the newly acquired American airfield at Munda Point.

The 172nd Regiment’s movement forward ceased two weeks after landing on Arundel, necessitating the deployment of elements of the 27th, 169th, and 103rd Infantry Regiments along with Marine tanks to secure the island from fanatical Japanese resistance.

However, the Japanese on Arundel were not resupplied due to continued U.S. Navy interdiction in the waters of Kula Gulf and Blackett Strait. Without supplies from Bougainville and the Shortland Islands, Sasaki, still on Kolombangara, sent the remainder of his 13th Infantry Regiment to Arundel on September 14 with the forlorn plan to attack Munda to capture foodstuffs.

Eventually, Sasaki ordered his Arundel defenders back to Kolombangara, which ended the fighting on Arundel on September 21. Sasaki lost more than 800 men on Arundel; however, the Japanese held up the American advance for more than three weeks. This enabled General Imamura and Vice Admiral Jinichi Kusaka, commander of the 11th Air Fleet at Rabaul, who was also in charge of all naval units in the Solomons, to bolster the defenses of both Rabaul and Bougainville. American casualties on Arundel were approximately 300 men.

Originally, Halsey’s plan called for the attack against Munda to be followed by the seizure of Vila airfield on Kolombangara. Correct estimates of the considerable strength of the Japanese garrison on Kolombangara numbered just under 10,000 troops. Halsey did not want another protracted campaign to capture Vila, so he decided not to attack Kolombangara as a prelude to moving into the northern Solomons. Instead, the Americans bypassed the heavily defended Kolombangara and prevented its resupply by naval and aerial interdiction.

The South Pacific Force seized the lightly held island of Vella Lavella, just 15 miles northwest of Kolombangara. U.S. Navy intelligence estimates placed the Japanese garrison there at roughly 1,000 troops. Halsey’s staff reasoned that Vella Lavella, the northernmost island in the New Georgia group, provided a forward airfield at Barakoma that could aid in severing enemy supply runs to Kolombangara while also serving as a base for American air support for future operations in the northern Solomon Islands.

On August 15, 1943, a Northern Landing and Occupation Force of over 6,500 troops—composed of the 25th Division’s 35th RCT, the 58th Naval Construction Battalion, the Army’s 25th Cavalry Reconnaissance Unit, and the 4th Marine Defense Battalion—landed virtually unopposed at Barakoma on the island’s southeast coast.

The Japanese had realized that to salvage the troops and equipment on Kolombangara they would need a nearby base; Vella Lavella’s northern tip seemed a logical locale. To facilitate establishing a base there at Honaniu, two companies of the 13th Infantry Regiment and some SNLF troops had been landed there by armed barges on the night of August 17-18.

Halsey noted that the mopping up of the Japanese on Vella Lavella was not moving according to plan. So he brought in reinforcements—the 14th New Zealand Brigade of the 3rd New Zealand Division—which arrived on September 18, 1943, to complete the forcing of the enemy garrison into the northwest corner of the island with a two-pronged offensive commencing on September 24.

There was never any substantial ground combat on Vella Lavella because Japanese forces were both limited and in the process of withdrawing. However, the enemy harassed the Kiwis’ advance through the jungles of Vella Lavella to stall Halsey’s campaign and gain additional time to strengthen the Northern Solomon Islands.

The sporadic fighting on Vella Lavella lasted until October 5-6, as the Japanese employed tenacious delaying tactics. The real struggle for Vella Lavella occurred with naval surface action and incessant aerial attacks on American shipping, which included more than 100 hundred enemy sorties from August 15 through September 3.

Halsey sent the Navy’s Seabees to Vella Lavella to restore the airfield at Barakoma. The intent was for American fighters with auxiliary fuel tanks to be stationed there for a roundtrip air assault on Rabaul.

The American admiral also established a Marine staging base on Vella Lavella for future attacks in the northern Solomons, such as the Marine parachutist raid on Choiseul in late October 1943. To accomplish this, elements of the I Marine Amphibious Corps (IMAC) landed some units from the 3rd Marine Division at Ruravai farther up Vella Lavella’s eastern coast in mid-September.

On September 20-21, as General Sasaki withdrew his Arundel forces, he also moved his troops off Gizo Island eastward to Kolombangara, which would eventually have over 10,000 IJA and IJN troops.

Two days later, the planning for the Kolombangara garrison’s withdrawal began. It was Sasaki’s responsibility to get these troops evacuated safely from Kolombangara’s northern coastal points and bays. This was accomplished by Japanese destroyers that received landing barges laden with troops from Kolombangara. The evacuation commenced on September 28 during a moonless night and brought those troops to Choiseul, a six-hour northerly voyage across The Slot.

By the end of the first week of October, the Kolombangara withdrawal was complete despite attempts by U.S. Navy surface vessels to disrupt the evacuations. Those troops from Kolombangara who were not diverted to Choiseul were sent to either Bougainville or to Rabaul; the evacuating Japanese troops from Vella Lavella were sent to the Shortland Islands off the southern coast of Bougainville.

General Sasaki had managed to maintain the integrity of his forces during both the combat on and skillful evacuations from the islands of the New Georgia group in the central Solomons. These Japanese forces were to soon fight Halsey’s northern advance again on the large northern Solomon Island of Bougainville from November 1, 1943, until the end of the Pacific War.

The American campaign for New Georgia and other islands in the central Solomon group from early July 1943 until the end of September was one the bloodiest fights in the South Pacific, although it has been overshadowed by the earlier six-month campaign on Guadalcanal. Halsey’s grueling advance on New Georgia, which was transformed into the keystone of Japanese defense in the central Solomons, culminated with the capture of Munda airfield.

However, this Marine and Army victory did not get the publicity that MacArthur’s New Guinea or Nimitz’s Central Pacific campaigns received. Instead, elite Marine Corps infantrymen, gunners, and tankers along with former National Guardsmen from New York, New Jersey, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., confronted the previously victorious Japanese troops amid a difficult climate and forbidding terrain, including fortified defensive positions often shielded from aerial assault by the extensive jungle canopy.

The victory on New Georgia and in the surrounding islands expanded the blueprint for success that was necessary in formulating the island-hopping strategy in the Solomon Islands and elsewhere in the Pacific Theater.

My dad part of the 4th Marine Raiders was part of the campaign Bairako Harbor. He was part of the crew that went through the jungle in thigh high mud. Was wounded on July 20.

“this Marine and Army victory did not get the publicity that MacArthur’s New Guinea or Nimitz’s Central Pacific campaigns received”.

And rightly so.

Noted historian Samuel Eliot Morison described it in his History of United States Naval Operations in World War II as “the most unintelligently waged land campaign of the Pacific war (with the possible exception of Okinawa)”.

Must have missed that one, eh, mr. Diamond?