By Ralph Segman

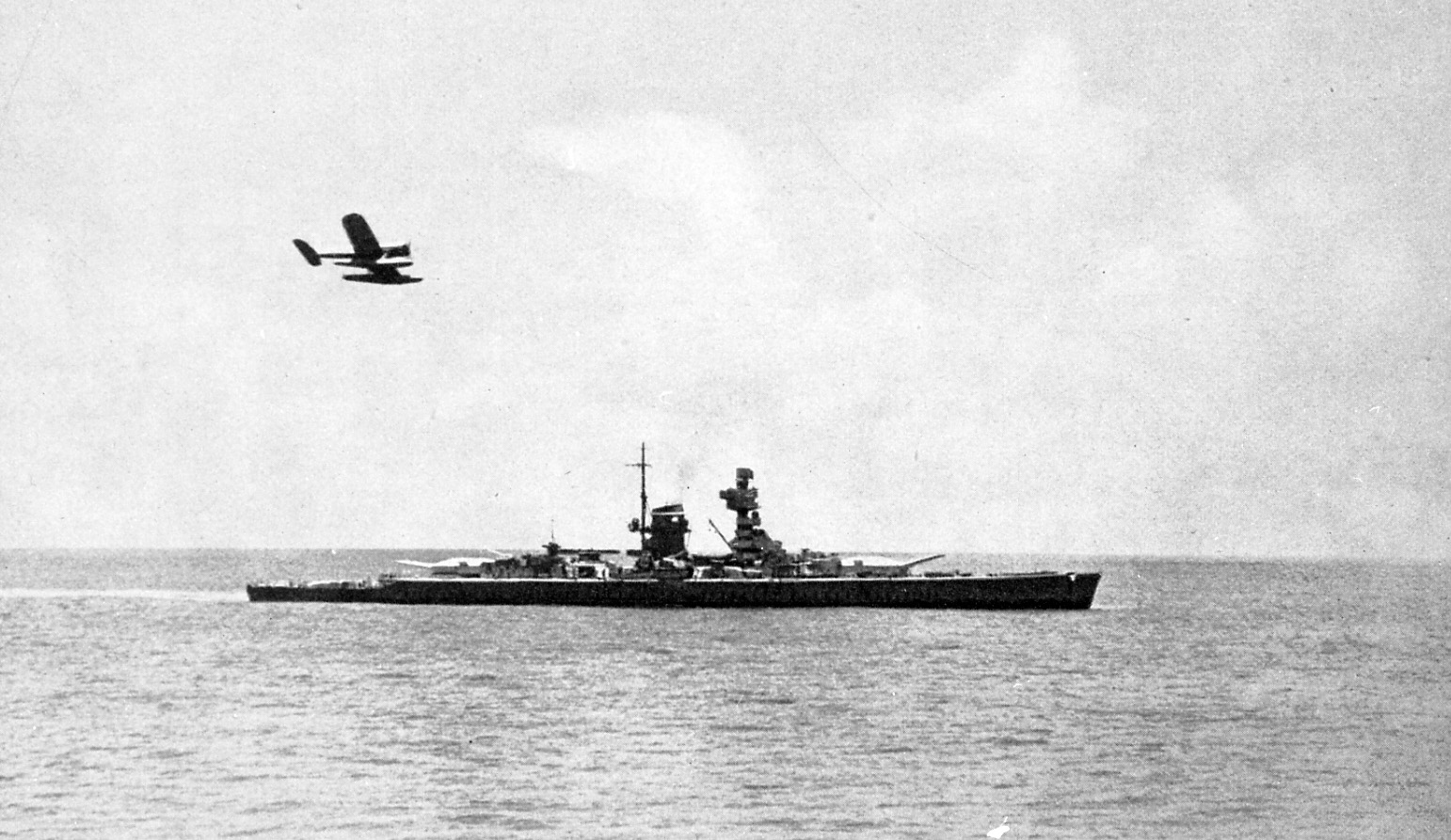

Say the words “pocket battleship” and up pops the name Admiral Graf Spee. Her two sister ships, the Deutschland/Lutzow and the Admiral Scheer are virtually unknown to Americans. The Deutschland deservedly belongs in the dustbin of naval history. On the other hand, the Scheer was the star of the entire German surface warship fleet.

The three panzerschiffe (dubbed “pocket battleships” by the British) were designed to prey on Allied trade routes. With their six 11-inch guns and 27-knot top speed, they could outfight smaller but faster warships and outrun bigger but slower ones. At the beginning of the war, only three old British battlecruisers, Hood, Renown, and Repulse, were capable of both outgunning and overtaking them. Merchant mariners feared them even more than U-boat packs.

The Graf Spee gained notoriety on her first and only wartime cruise. Leaving Wilhelmshaven 11 days before the war started, she sank nine cargo ships totaling 50,089 tons by December 7, 1939. She was ambushed by three Royal Navy cruisers and forced into the neutral harbor of Montevideo, Uruguay. Given three days to repair and leave, the Germans were misled by reports that a major British task force was approaching the harbor. Berlin sent orders to scuttle. The pocket battleship sailed just outside the harbor and, at sunset, six torpedo heads exploded and gave 750,000 waterfront spectators a tremendous sound and light show. Three days later, the Graf Spee’s Captain Hans Langsdorff killed himself. Thus, the Graf Spee, with a short and mediocer career as a commerce raider, became a legend.

The Deutschland was a hard-luck ship from start to finish. A half-hour after she arrived at Ibiza during the Spanish Civil War on May 29, 1937, two Republican aircraft approached out of the sun and hit her with two 110-pound bombs. She suffered considerable damage and 141 casualties, 31 of them deaths.

In October 1939, the Deutschland sank two freighters in the North Atlantic, her tally for the entire war. During mid-ocean refueling and reprovisioning in a November storm, her superstructure was split in several places and three motor rooms were flooded. At Grand Admiral Erich Raeder’s suggestion, Adolf Hitler changed her name to Lutzow, mainly to offset an enemy propaganda advantage should she be sunk.

During the Norwegian campaign in April 1940, the Lutzow was heavily damaged by 5.9-inch shore batteries. On the way back to Germany, she was torpedoed by the British submarine Spearfish and had to be towed to Kiel. Repairs kept her out of action for more than a year. She had hardly taken to the sea again when, on June 14, 1941, a torpedo bomber sent her back to a Kiel drydock. After seven more months out of the war, the Lutzow sailed into an ice-ridden Baltic and sustained propeller damage. She made it back to Swinemunde for four months in a shipyard.

On July 2, 1942, as a primary player in an operation to attack convoy PQ 17 on the Murmansk run, the Lutzow ran aground in Tjeldsund. Several holes and dents in her bottom necessitated a return to Kiel. She arrived, only after a tortuous, multilayover passage, on August 17. During the two months of repair work, several onboard fires and one in the dockyard occurred. As the pocket battleship left Kiel, she struck a floating crane, leaving the left gun of B turret out of true.

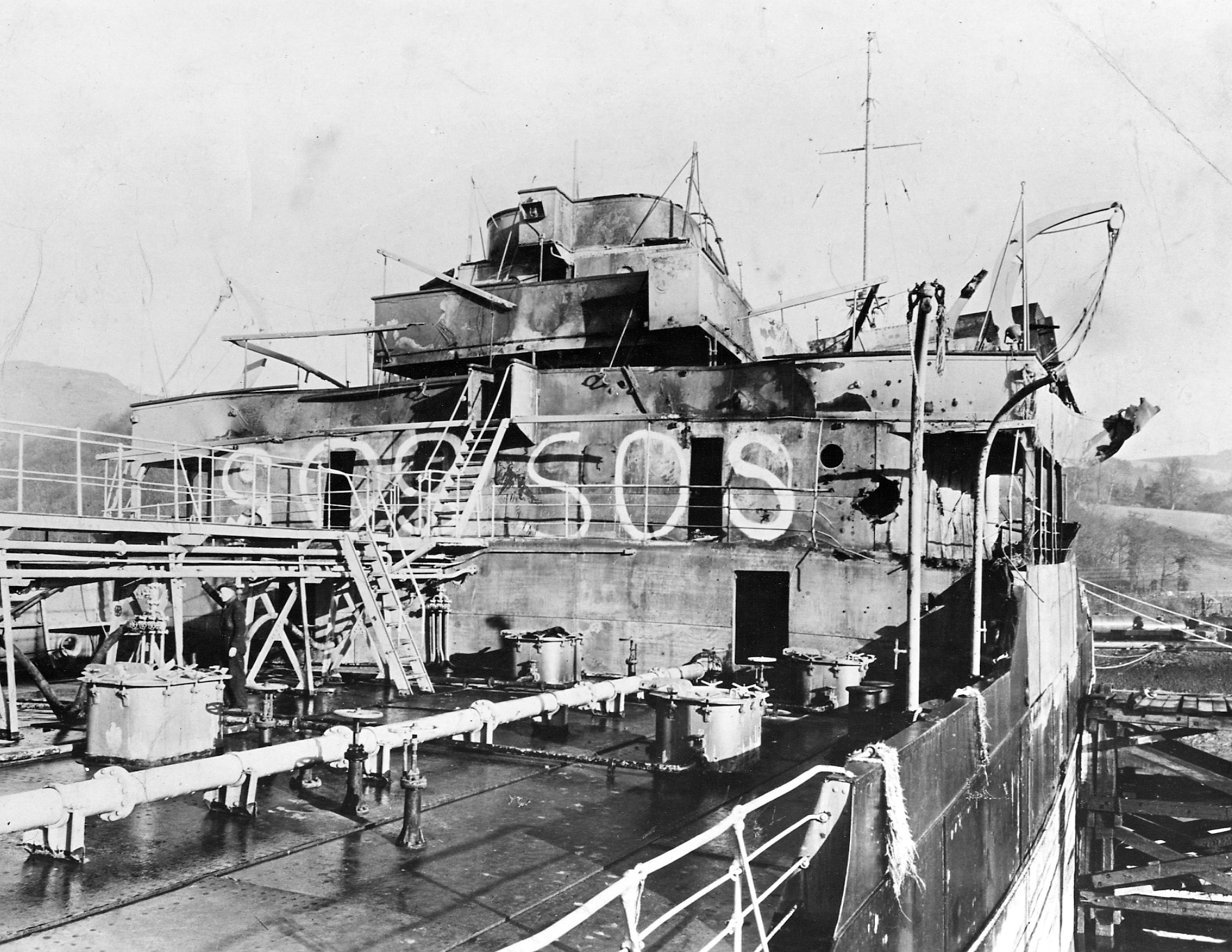

Except for the failed Operation Rainbow against Allied convoy JW 51B in December 1942, in which her guns were silent, for the next two years she passed most of her time in quiet coastal waters or in shipyards for refits or diesel overhauls. In September 1944, the Lutzow and other ships were in Finnish waters protecting German troops from advancing Soviet forces. Shore bombardment continued sporadically a few days at a time from October to March 1945. While docked in Swinemunde in April to rearm, 100 feet of her port side were torn open from a near miss by an Avro Lancaster’s five-ton bomb.

After a patching up, her final captain, Ernst Lange, took her out again to shell Soviet troops. When she ran out of ammunition in early May, with Germany about to surrender, charges were set to scuttle her. In a final blow by her incubus, the explosives detonated prematurely as a result of a shipboard fire.

Good fortune smiled upon the 13,660-ton Admiral Scheer during most of her lifetime. Overall, her one and only commerce-raiding cruise was a resounding success. She ran 46,419 miles in 161 days from the Baltic Sea around the Cape of Good Hope into the Indian Ocean and back to Germany, accounting for 17 Allied ships (128,000 tons).

At the beginning of the war, the Scheer was anchored at Schillig Roads off Wilhelmshaven. On September 4, the watches were relaxed. A ship’s officer and a Luftwaffe flier were studying aircraft recognition charts. They were interrupted by the blare of a loudspeaker: “Three aircraft at six o’clock. Course straight toward the Scheer.”

Inexperienced radar operators identified them as German Heinkel He-111s. It did not take long for the Luftwaffe officer to shout: “They’re not ours. They’re Bristol Blenhiems.”

Royal Air Force Squadron 110, led by Flight Lieutenant K.C. Doran, approached under low clouds, altitude about 500 feet. They spotted the Admiral Scheer straight ahead. Doran came in just over mast height and dropped two 500-pound bombs. Both ricocheted off the deck and superstructure and chunked into the water. They did not explode because their fuses needed 11 seconds to arm, not possible from their low level of release.

Such luck became a trademark of the pocket battleship.

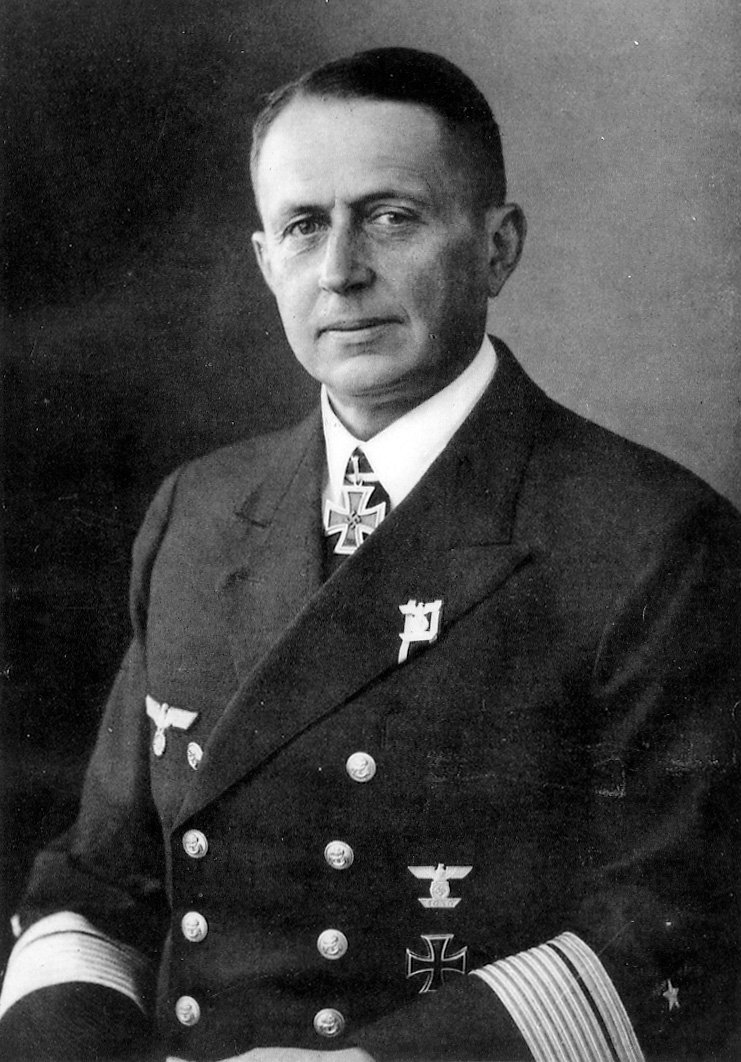

At the end of October, her command was handed over to Captain Theodore Krancke. He took the ship on uneventful cruises in the Baltic and the North Sea. On February 1, 1940, the Scheer docked in Wilhelmshaven for a refit and a major overhaul of her eight linked diesels. Her bows were raked and her pagoda-like fighting mast was replaced with a lighter tubular structure. Her foretop was remodeled to accommodate an FuMO 25 radar system. As part of the overhaul, the engine’s underpinnings were rebuilt to reduce vibrations, which had stressed the crew and interfered with fire control.

The layup took five months, during which most of the German Navy was involved in the invasion of Norway. While the land fighting went well for them, their small fleet took damage and major losses. Had the Scheer been in the battle, she could well have been hit hard. As luck would have it, she was high and dry in the Wilhelmshaven clinic. By the end of June, she was ready to sail, and Krancke, who had been tapped to head naval planning for the Norway operation, returned to his bridge.

After three and a half months of crew retraining, sea trials, repairs, adjustments, and exercises with the Nordmark, her designated mid-ocean supply ship, the Scheer sailed out of Gotenhafen on October 23. It was her first commerce-raiding cruise. That night, in the Great Belt between the Danish islands of Fyn and Sjaelland, a propeller was fouled by the chain of an unmarked navigation buoy. She hove to, and a diver dropped off the stern. By noon the next day, she was underway. Crossing the Kattegat, the Scheer was ordered to turn back to Kiel to avoid British submarines in the Skaggerak. She passed through the canal, and, four days late, headed up the North Sea.

Although the Scheer was to encounter good fortune throughout her wartime career, this delay was the first of three spates of bad luck that blemished her encounter with Convoy HX 84 and its sole escort, the armed merchant cruiser HMS Jervis Bay, which had been converted from a passenger liner.

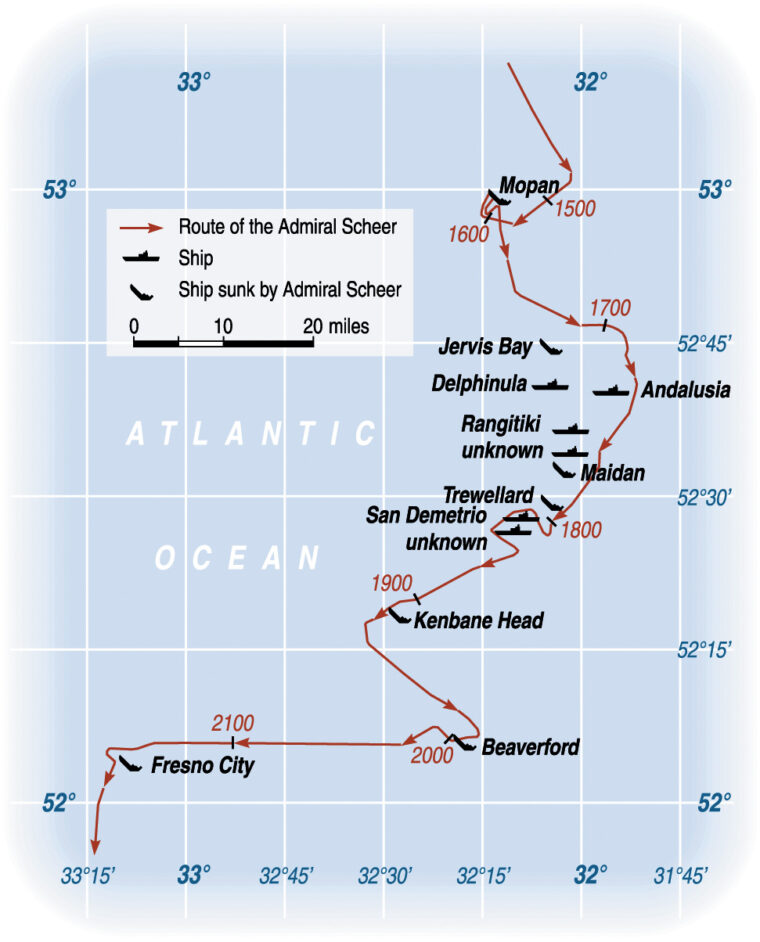

Krancke’s mission was to attack a convoy on the Halifax to Britain run. His destination was a square in the North Atlantic bounded at 52-54 degrees north and 32-35 degrees west. The German high command believed most HX convoys passed through the approximately 120-by-120-square-mile area. They expected HX 83 and HX 84 to be there between November 4 and 6.

On her breakout via the Denmark Strait, the Scheer passed painfully through an extremely powerful hurricane, with waves as high as 100 feet. She lost two crewmen overboard, and her sickbay filled with injured men. Unsecured equipment and loosened fittings ricocheted off bulkheads. Seawater, washing through opened ventilators, damaged food supplies. Two motorboats were severely damaged. The captain and the helmsman were slammed into a corner of the bridge. The ship reached the target area on November 3, but the heavy seas kept her Arado scout plane perched on its rails. No convoys were sighted that day or the next. A calm November 5 dawned with a slowly advancing overcast to the north and clear skies to the south.

The seaplane took off, flew a fruitless triangular pattern, and returned with no news. Reconnoitering a second sector, the pilot came back quickly with a multiship sighting 88 sea miles to the south—about three hours of top-speed sailing. The officers and crew cheered; they were about to engage in their first action after 14 months of war.

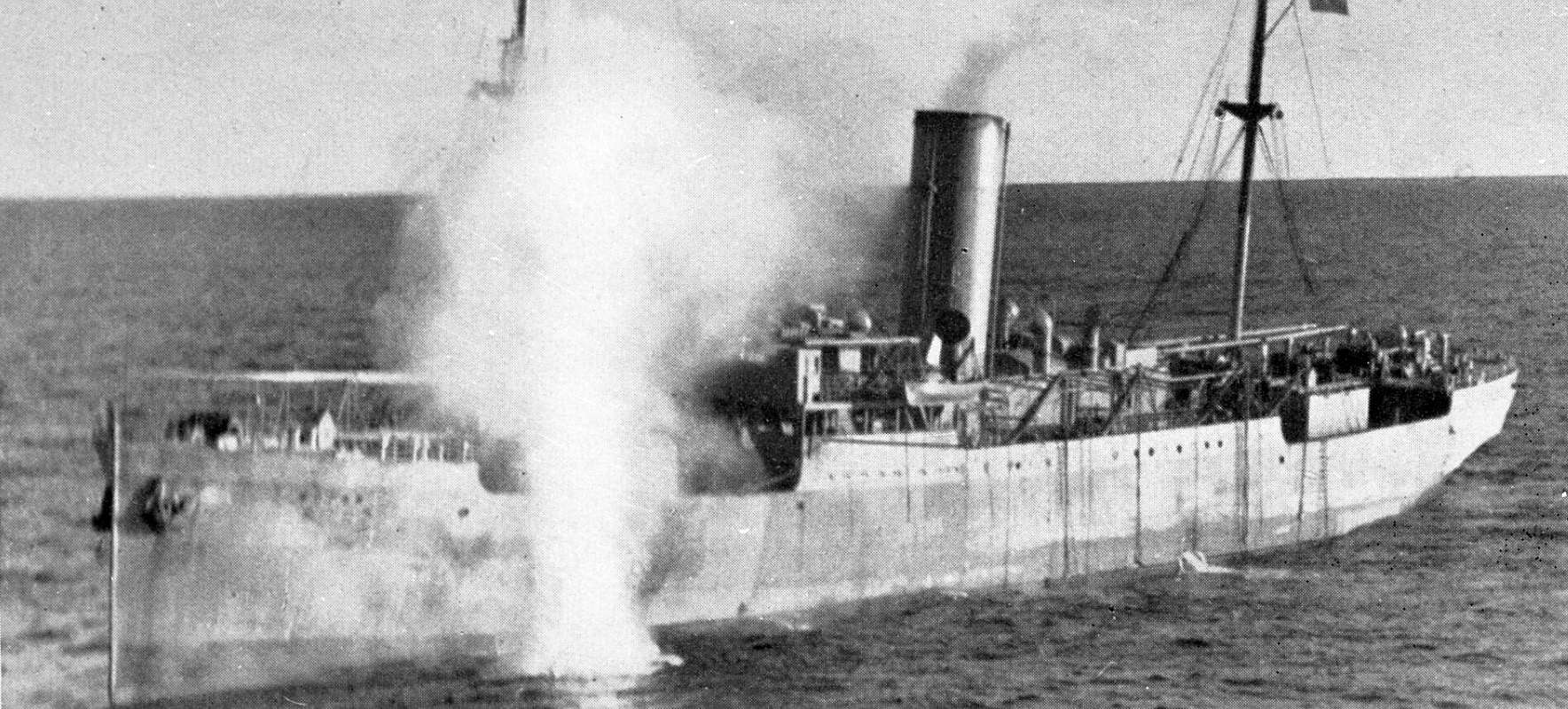

About 2:15 in the afternoon, spikes appeared on the radar screen. The new technology was not refined enough to distinguish the proximity of any of them. At 2:27, the Scheer’s lookout reported smoke at 50 degrees, much earlier than expected. Only a smudge, it puzzled Captain Krancke, who thought it might be an armed merchant cruiser scouting ahead of the convoy. It turned out to be the 5,400-ton Mopan, carrying 70,000 stems of bananas from Jamaica. She had overtaken and declined an invitation to join the slower convoy.

Krancke signaled the banana boat to maintain radio silence, which she did as her crew abandoned her and rowed slowly toward the pocket battleship. Wishing to avoid endangering the men in the lifeboats, the impatient German captain moved his ship to one side and sank the Mopan with 4-inch antiaircraft weapons and 1.5-inch rapid-fire guns.

By the time the British prisoners were taken aboard the Scheer and she got underway again, it was 3:30. A full hour had been lost, the result of her second brush with misfortune. The earliest possible encounter with the convoy now was a half-hour after the 4:31 sunset. Twilight would last another half-hour. Krancke figured that while darkness would be a problem, the radar would give him a major advantage. Earlier, after the Arado’s sighting, he had considered several alternatives: attack at once, despite the lateness of the day; wait until morning, though that would move his ship 130 miles closer to the Western Approaches and the Royal Navy; or wait a few days for HX 85. His impatience, like his crew’s, ruled the day.

At 4:30, a profusion of masts began growing against the sky. Silhouetted superstructures and then hulls appeared. After scanning the horizon for warship escorts, Krancke mused aloud: “Have they got no protection at all?”

“There’s only one ship there with what strikes me as an unusual deck structure for a freighter,” said navigation officer Lieutenant Peterson.

“Looks like some sort of auxiliary cruiser,” said the captain. “She’s turning out of line now. I should say they’ve spotted us.”

When the distance between the Scheer and the convoy’s apparent escort, which was coming straight at his ship, shrank to 10 miles, he ordered his 11-inch guns trained on the armed merchant cruiser and his 5.9-inchers on a tanker close to her. Then he noticed that the escort captain put his ship in front of a large two-funneled cargo liner (the Rangitiki). He thought it might be a troop carrier. He would get to her after taking care of the 14,164-ton Jervis Bay.

On identifying the pocket battleship to the north, Captain Edward Stephen Fogarty Fegen suggested a 40-degree starboard turn to the convoy’s commodore, H.B. Maltby. Then he brought the Jervis Bay up to full speed, 15 knots, and executed a sharp port turn straight at the Scheer.

At 5:15, Krancke ordered a ranging salvo from the Scheer’s forward turret. Twenty-three seconds later, three 200-foot spouts appeared almost simultaneously about 50 yards short of the escort’s bows. Maltby immediately launched a series of Very rockets signaling the convoy to scatter, proceed with the utmost speed, and make smoke. M.L. McBrearty, second officer of one of the freighters, later wrote: “‘Scatter’ meant just that. You were now on your own and had to find the best way out.”

Krancke wondered whether the rockets were a signal to scatter or to alert escorts on the other side of the convoy. He decided, risk or no risk, he would continue attacking. Before the raider’s corrected second salvo from both turrets came down, he could see gun flashes on the escort. The enemy gun crews, he thought, were ready and well trained. Their first few splashes fell several thousand yards short. Probably maximum range, the German captain thought. This helped him choose his first tactic: pound the escort from beyond her range until she sinks or is beaten into impotence. Then chase down the convoy ships.

A few seconds later, the Scheer was sprayed by a near miss. A freak cordite charge had given one of the escort’s shells a prodigious flight. This troubled Krancke. Was the British armed merchant cruiser capable of drilling his ship with 6-inch shells? Any damage would make the pocket battleship more vulnerable in the expected Royal Navy search, but no other shots came near and his concern melted away.

The Germans’ second ranging salvo came down just behind the oncoming Jervis Bay. It was good bracketing.

During the first few minutes of the battle, the Scheer also targeted the 8,100-ton tanker Delphinula. After being straddled by the first ranging 5.9-inch salvoes, the tanker captain ordered a smoke float attached to her starboard quarter and ignited. It glowed intensely red and produced heavy smoke, giving the impression the ship was burning. Three more floats were tied to the port side and lighted. Krancke believed she was destined to sink, and he decided to waste no more shells on her. The Delphinula entered a nearby smoke screen and escaped to the north.

The Scheer’s third 11-inch salvo hit the target. One of the 780-pound shells took out part of the Jervis Bay’s bridge, severely wounded Captain Fegen, killed several officers, and destroyed the radio room, generators, and backup batteries, leaving the director, the range-finder, and the fire-control equipment out of action.

Sometime between the first and third salvos, the Scheer experienced her third stroke of bad luck. The muscular recoils of her big guns cracked the radar crystal and put the ship’s key spotting and ranging device out of action. Although the fire-control system was now degraded, it remained superior to anything the Royal Navy had at that point in the war. Smoke screens and the deepening dusk diminished the Germans’ ability to detect convoy ships. By dark, the raider’s success would depend on fate and searchlights.

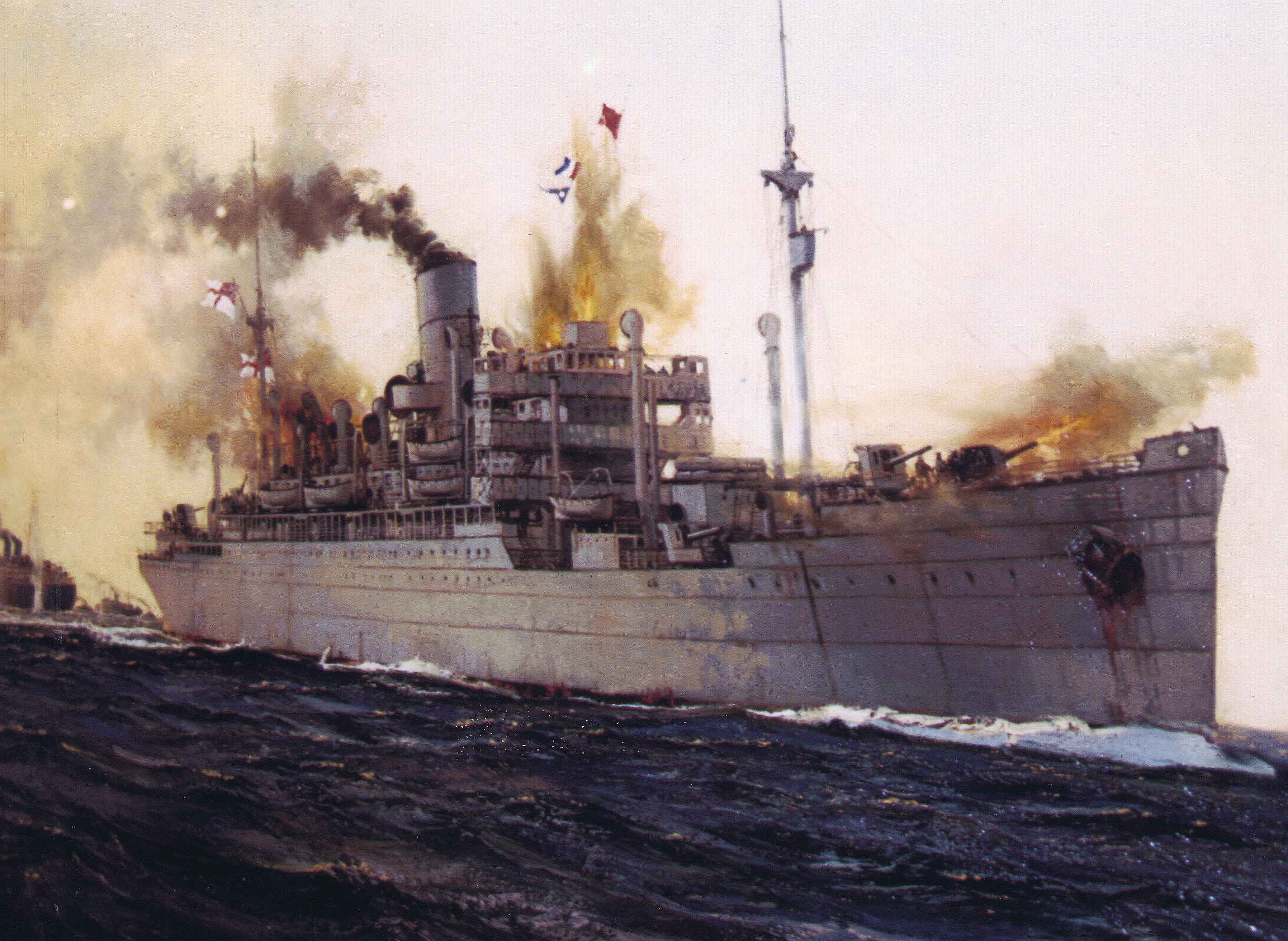

Krancke kept pounding away at the Jervis Bay. In 15 minutes, the vulnerable convoy escort was in flames and much of her superstructure was jagged wreckage. Her main and after steering controls were lost, and her seven guns were silent. But she was not sinking. The German captain almost irrationally insisted on putting her under before concentrating on the cargo ships. He did not know the escort’s former cargo spaces and ‘tween decks were loaded with 24,000 sealed, empty 45-gallon barrels to retard her sinking. In the early darkness, he mistook flashes of exploding cordite bags on the Jervis Bay’s decks for gunfire, giving him another reason to keep the big guns on her. Finally, after an hour of dealing with Captain Fegen’s “close the enemy” tactic, he shifted his primary attention to other ships.

Krancke swung his main turrets to the 16,698-ton Rangitiki, the supposed troop ship, which actually carried 75 passengers and several thousand tons of cargo. Keeping his medium guns on the Jervis Bay, he ordered ranging salvoes on the next target. Captain H. Barnett turned the big freighter to the starboard toward a smoke bank. The first projectiles fell about 500 yards short on the starboard side. As the Rangitiki began dissolving like an apparition into the outer smears of smoke, the second salvo straddled her amidships. The third set of shells got within 50 yards, spraying the bridge and forward areas with sea water and splinters.

Krancke believed the last salvo hit the ship’s stern. The final German shots were fired blind, one of which, because of the way the screen lighted up, they wrongly thought was a hit. The cargo liner swung northwest behind the smoke and ultimately reached a British port with minor shrapnel wounds. Without the distraction of the Jervis Bay, Barnett later said, the raider “could have picked off the ships of the convoy one by one.”

The action had been underway for about an hour and ten minutes, and the Scheer’s captain could claim no confirmed sinkings, not even the tortured escort. He headed south into the dispersing array of merchantmen. This maneuver raised the risk of collision in the dark and put the Scheer within range of their small caliber but potentially damaging guns. At 6:11, the 7,900-ton iron and steel carrier Maidan loomed, barely visible, at short range. All the raider’s starboard armament opened up on her. Within moments, she was engulfed in flames and sank like a cast iron anchor.

The burning Jervis Bay remained the most visible object in the darkness, and Krancke sporadically ordered his medium gunners to pepper her until she receded out of range. With thousands of steel barrels rolling out of the holes in her sides, she finally sank about 7 pm

German spotters soon located another ship by the gun flashes on her poop. She was another iron and steel freighter, the 5,200-ton Trewellard. The Scheer’s first projectile entered her after hold, hurling pig iron into the sea and silencing her gun. A second shell pierced the port side of the engine room and lifted chunks of machinery out through the skylight. Although her cargo was dead weight, she went down more slowly than the Maidan, and 25 of her crew survived in three lifeboats.

The 8,100-ton tanker San Demetrio had just maneuvered away from a near collision with another convoy ship and headed straight at the Scheer. She came under fire and was hit by the third salvo. The tanker captain, convinced the 11,200-ton cargo of aviation fuel was going to turn his ship into a huge incendiary bomb, ordered his men to abandon her. A few minutes after three loaded lifeboats hit the water, “the San Demetrio was blazing furiously,” one of her officers said. Two days later, 14 men in one of the lifeboats reboarded the ship, doused the fires, repaired equipment, nursed her through a storm to her Rothesay Bay destination port, and discharged her precious cargo at an oil dock.

The pocket battleship then established a southwesterly track, and after a while her sharp-eyed observer spotted a faint silhouette. Krancke swung around so that the port side faced the dark form. A searchlight illuminated a freighter about two miles off the beam. Before its crew had a chance to react, the 5,200-ton Kenbane Head, with a general cargo, began taking hits from 5.9-inch shells. The lifeboats were destroyed, but they got two jolly boats and a raft overboard, and 20 men lashed them together as a makeshift catamaran. About 7:30 pm, the ship sank.

The Scheer’s big gun crews took a break on station. The tight turret chambers were stifling. Jutting instruments, controls, dials, levers, and other gear contributed to the crowding. The men rested against the little available wall space or they squatted. Their faces and torsos were smoke-blackened, and rivulets of sweat left dirty white patches and trails on their foreheads, cheeks, necks, and down their backs. The big, gleaming breech blocks, each containing a shell, were closed and ready to fire. Empty brass casings rolled and clanged together as the seas mounted.

After a while, a lookout spotted another dark shape. Alarms rang and the gunners hurried to their stations. This time, instead of a searchlight, Captain Krancke ordered small incendiary shells, which lighted up the quarry when they hit her. The 10,000-ton Beaverford carried a load of maize, meats, cheeses, aluminum, copper, munitions, and chemicals in her holds and timber on her deck. Fires broke out in several areas then she was torn open by 11-inch projectiles. She had been transmitting details of the battle. Krancke heard the doomed vessel’s final message: “It is our turn now. So long. The Captain and Crew of the SS Beaverford.”

She was slow sinking. The timber cargo was propping her up. The Scheer’s big guns had registered three hits, and her 5.9-inchers 16 hits. Rather than expend more of his dwindling supply of shells, Krancke ordered a coup de grace: “Torpedo tube number 8, fire.” The explosion raised the forward section out of the water, and the Beaverford quickly heeled over and plunged bow first—no survivors. The time was 8:30.

The German captain felt he had completed the first phase of his mission to sink Allied merchantmen and disrupt the operations of the Royal Navy. He expected the British to have already mounted a massive search for the Scheer. Their ships probably were converging on the battle scene and moving to cut off possible escape routes. Krancke’s task now was to put as much due-west distance as possible between his ship and the hunters.

At 9:17, the relaxing gun crews were jolted back to their posts by the action-station alarms. Moving to about 3,000 yards range, the captain ordered the searchlight on, and the 5,000-ton Fresno City lit up like a movie screen. The guns fired independently, a mix of 11-inchers and 5.9-inchers. Six shells almost immediately penetrated the maize-carrying freighter. Thirty-five survivors in two lifeboats pulled away from the blazing hulk, which remained visible until she sank at 3:35 am.

The final score on November 5 was five convoy ships, the escort, and the Mopan. Although it may seem unjustified to claim that sinking seven ships in a single action was a dismal failure, the Scheer was fully capable of destroying the entire 37-ship convoy. Her missed opportunity had several roots. Most pivotal was the Jervis Bay’s Nelsonian charge, which had immediately drawn Krancke’s attention and held it for a good hour and a half while the HX 84 freighters and tankers scattered into the night and the mounting gale. Captain Krancke’s decision to shell the Jervis Bay until well after she had been beaten into impotence botched what might have become Germany’s greatest sea victory. Captain Fegen was posthumously awarded the war’s only Victoria Cross for convoy defense.

Another factor was the Scheer’s four-day timetable setback at the beginning of her cruise, which brought her into contact with a smart, tough opponent. The hour lost in her unexpected encounter with the independently sailing Mopan delayed her engagement with the convoy until a half-hour before nightfall. And her ability to spot and range the convoy ships at night was seriously degraded by the destruction of her radar crystal.

In another sense, the outcome of the attack was a rousing success. All told, the British hastily assembled five widely dispersed task forces totaling two battleships, three battlecruisers, an aircraft carrier, five cruisers, and 15 destroyers to hunt for the Admiral Scheer. The search kept the Royal Navy scurrying for two frustrating weeks before it was called off. Several convoys returned to their ports of assembly; others remained in their ports. Harbors became congested and chaotic. At this time when every shipload was critical, cargo deliveries were delayed up to two weeks. According to naval historian Captain S.W. Roskill, “The loss of imports caused by the pocket battleship’s sudden appearance on our principal convoy route was … far greater than the cargoes actually sunk by her.”

Krancke’s run of bad luck and costly command decisions took an about face for the remainder of the pocket battleship’s cruise. He headed west at full speed for a while, then he swung south toward a rendezvous with the supply ship at Point Green near the Tropic of Cancer. Just after noon on November 16, the 23,000-ton Nordmark, manned by friends who had trained with the Scheer’s crew, steamed into view. Krancke called out the ship’s band to celebrate the occasion. The bandleader mischievously considered playing “The Star Spangled Banner” in recognition of the Nordmark’s masquerade as an American merchantman with the name Prairie on her bows and a big U.S. flag painted beneath. But, as he later told the captain, he thought better of it.

Refueling the pocket battleship was tricky, with swells so heavy that at times the ships were not visible to each other. The Nordmark moved slowly ahead, and the Scheer fell about 300 yards behind her. The tanker dropped a light line off her stern. Its end was kept at the surface by a balloon. It was caught and lifted to the bow of the trailing ship, followed by a somewhat thicker line that was tied on, then a strong rope that, in turn, was attached to a heavy towing hawser. Under the urging of the first officer and a rhythmic whistle, a musclebound crew lugged the hawser aboard and made it fast to the tow stanchion. Grasping two lines that came up with the cable, they lifted two diesel-oil pipelines from the tanker and connected them to the fuel intakes.

The Nordmark took the Scheer under a slow tow to keep the ships from drifting apart and rupturing the slack fuel lines. During the several hours it took to top off the bunkers and for the next two days, every boat was used in the heavy seas to replenish the raider’s ammunition and other stores. One 11-inch shell was damaged, and a keg of beer was dropped three decks. None of the crew was injured. The hazardous operation was a remarkable success.

On November 24, about 400 miles southeast of Bermuda, a lookout spotted a square-built ship with big cases on her deck. The Scheer turned, and Krancke set a top-speed collision course. The wireless room picked up the British “RRR” (raider) signal from the 7,500-ton Port Hobart. The German captain’s tactic was to allow the freighter to continue signaling, draw Royal Navy search groups to the area, and be long gone before they arrived. He raised “Heave to” pennants, but the ship showed him her stern and a boiling wake. “What the devil does he think he’s up to,” growled Krancke, who did not like using unnecessary violence. “Warning shots over the bow.”

The Port Hobart stopped. A crew headed by a Lieutenant Engels boarded her and went to the captain’s cabin. “How many people on board?” Engels asked. “Sixty-eight,” the captain replied. “There are eight passengers, seven ladies and a man. What’s going to happen to the ladies?”

“If they behave themselves like ladies they’ll be treated like ladies.”

“Did you identify us in your wireless?”

“Unfortunately not,” said the captain.

The deck began piling up with items the prize crew wanted to take back to the Scheer, such as nautical instruments, tables and charts, nautical text books, coils of rope, ship’s tackle, machine tools, and small arms. At the captain’s insistence, a door was forced open with a crowbar, revealing a large supply of Scotch. They were interrupted by a sudden “abandon ship” shout. The scuttling crew had set the fuse timers prematurely. Engels and his three men remained on the bridge where they felt safer. Five explosions went off in quick succession, and the ship began to heel over. The last boat, standing 200 yards off, picked them up.

Then Engels remembered: “There should have been two more charges.”

They were about 100 yards off when two more explosions ripped through the hull. The freighter refused to go down. Several shots with an antiaircraft gun finished her off. The Port Hobart, which had been held in port for 10 days after the HX 84 convoy attack, finally sank with her cargo of airplane parts, paint, phosphates, paper, lubricating oil, linoleum, and slate.

After taking the 68 prisoners aboard, Krancke moved the Scheer due east and settled in an area southwest of the Canary Islands, where he felt he could strike again, unexpectedly. He claimed the radar was working again, although he had left no reports on its repairs or operations.

On the late afternoon of December 1, about 500 miles off the Canaries, a lookout sighted smoke and then two masts. Krancke kept the raider at the edge of visibility, hoping the other ship would not spot her. At nightfall and moonset, the captain rang for 23 knots and depended, he said, on the radar’s rotating “mattress” antenna to keep the target in view. At a range of 1,000 yards, a searchlight lit the freighter brilliantly. She was the 6,242-ton Tribesman, carrying electrical equipment, bicycle parts, wire, cloth, photographic materials, glass items, drugs, and mail.

She began turning away, and men were running to the stern gun. Krancke threw a medium shell across her bow and signaled: “Heave to. Don’t use your wireless or we fire.” Another searchlight to the stern revealed her gun crew elevating their 4-incher and swinging it around. He puzzled for a moment over the cargo ship captain’s audacity, then ordered one medium gun to open fire. Almost simultaneously, a shell buzzed over the Scheer.

“Good Lord, they’re firing back,” said the Scheer’s meteorologist.

The pocket battleship blasted away with all her starboard 5.9-inch guns and antiaircraft artillery. After his ship took 22 rounds, the British captain told his gunners, who had continued firing at the two blinding searchlights, to abandon their station. Krancke ordered a cease- fire. He took two boatloads of 76 men aboard as prisoners. To his dismay, he learned that a motorboat had been lowered off the far side of the ship with her captain, first officer, chief engineer, and 18 other crewmen aboard. Since she was not sinking, he sent a scuttle crew to finish the job. The motorboat was allowed to escape, and the raider moved away from the site.

Captain Krancke relaxed in his darkened cabin, his nose glowing softly with each draw on his invisible black Brazil cigar. He played a mind game imagining himself as an Admiralty officer. How would he react to the sinking of the Port Hobart and six days later the Tribesman 2,000 miles east. As a fantasized British admiral, he suspected it was the work of the Scheer, which must have laid low for about two weeks after her attack on the Jervis Bay convoy. He then visualized the British analyzing past actions and movements of the Scheer and her two sister ships, finding out who the captain is, and predicting his next move.

After some hours of immersion in this exercise, the captain concluded that the Royal Navy would watch for his ship at more southerly latitudes close to Africa. There, they would think the pocket battleship could prowl the Cape Town-Freetown shipping lanes and, like the Graf Spee, she could quickly cross over to the heavy trade routes off South America.

Krancke set a course to the northwest, figuring that if he attacked a merchantman in that region and the position were radioed by the victim, the Admiralty would reckon they had been wrong about his intentions. They might think that the ship was sailing to a home port, and they would set out to intercept her heading to the Denmark Strait or Brest.

The Scheer cruised around an area about 1,500 miles due west of the Canaries for 10 empty days. The captain’s imagined chess match produced no results. Moving southeast-by-south, the ship was refueled and reprovisioned by the Nordmark a few miles north of the equator. On December 18, operating astride the South America-Freetown trade route, where Brazil and Africa jut closest to each other, Krancke sent out his scout plane. The pilot discovered a freighter paralleling the raider’s course.

As the Scheer approached from the stern, the 8,654-ton Duquesa radiated “RRR” calls. The Germans fired two warning shots before the freighter slowed down and hove to. The boarding party discovered she carried 9,000 tons of meat, vegetables, and fruits; 15 million eggs; and whiskies, wines, liqueurs, and stores of other goodies. After transferring 43,000 eggs and several tons of meat to the Scheer, the captain considered taking her as a prize and sending her home. He was told, however, that she carried only enough coal to take her as far as Freetown. Since raider supply ships carried no coal, the Duquesa became a welcome member of the little German mid-ocean fleet and was christened “The Floating Delicatessen.”

As the Scheer took a hunting and evasion run to the southeast, the British deployed three task forces comprising two aircraft carriers, four cruisers, and an armed merchant cruiser. They cut off escape routes to the north and, of course, never sighted the raider. Again, Captain Krancke caused disruption in Royal Navy operations and then disappeared like a wraith.

The Scheer’s chief engineer felt that the diesels, having run almost continuously for two months, needed overhaul. He and the black squad labored below with the ship underway and temperatures well over 100 degrees. The engine room deck was slippery with their sweat. They removed the cylinder covers, lifted out the heavy shafts, and cleaned and reconditioned them. One cylinder was replaced, a job that required .01 millimeter precision by the machine shop. The overhaul, to be completed by January 5, included maintenance and repair on electrical apparatus, armament, and safety and firefighting equipment.

They sailed to Point Andalusia, one of their mid-ocean rendezvous sites, for resupply and a Christmas gathering with the Nordmark, the auxiliary cruiser Thor, the tanker Eurofeld, and the Duquesa. Krancke opened the hatches of the Duquesa and invited anyone in the fleet who could send a boat over to loot her refrigerators and shelves. On finishing the overhaul as scheduled, prisoners from the raiders’ operations, including the seven Port Hobart women, were transferred to the Storstad, a Norwegian tanker captured by the Thor a few days before, until 600 of them were packed in makeshift secure quarters.

The Scheer then swung into a northeasterly course toward the Gulf of Guinea shipping lanes. Along the way, Krancke stopped the engines and hove to for several days, until the moon had moved well away from its brightest phase. He anticipated night action not far from the Royal Navy base at St. Helena, and he wanted darkness to cut the risk. He also reasoned that the British would not expect an enemy surface raider to be in a region they controlled. Again, it was a chess match. One could never be sure of the countermoves.

To mask the defining triple turret characteristic of pocket battleships, one gun in each turret was lowered out of sight and the other two were raised slightly. The captain also had the Scheer painted in a British zigzag camouflage mode to slow down recognition of her German origin. Every minute’s delay in identification would add to the Scheer’s attack and escape advantage.

Krancke restarted the engines on January 14. Three days of leisurely cruising in a northeast-by-east direction brought them to the main lanes connecting Freetown and Cape Town. On the 18th, a lookout reported smoke. Using the radar to dog the unknown vessel, the raider kept out of sight until nightfall. Then the diesels jerked her into high speed and took her into a parallel course a few hundred yards from the other’s starboard side. In the sudden glare of a searchlight, the stranger turned out to be the Norwegian tanker Sandefjord carrying 13,000 tons of crude. She did not transmit “RRR” signals, thus saving her skin, and she was taken over by a prize crew.

On the morning of January 20, a northbound cargo ship was sighted. The Scheer began tailing her in the same tactic she had used with the Sandefjord. At 3 pm, the radar spotted another ship heading south. Shortly after lighting a black cigar in his creative mode, Krancke turned to his officers and told them they were going to get two for the price of one: “I think the time has come to use a little guile.”

He rang for full speed and turned east, away from both freighters. Out of sight, he came about and waited until they were about to pass each other along the Scheer’s line of sight. Then she moved at top speed toward the nearer southbound ship. As the other one disappeared behind her, Krancke altered course slightly to the south. This kept the raider hidden from the northbound merchantman while approaching the first target. When the Scheer’s signalman flashed the British recognition code “M.A.G,” the freighter showed her stern, the normal reaction on sighting another vessel, and then she blinked a response.

“Have secret orders for you,” flashed the German. “Put about to facilitate delivery.”

The 5,200-ton Dutch cargo carrier Barneveld reversed her course and approached the supposed British warship. By the time her captain recognized the pocket battleship, it was too late to transmit an “RRR” signal, despite the insistence of a British lieutenant, one of 51 Royal Navy passengers. The armed prize crew discovered to their chagrin that they were outnumbered nearly four-to-one by enemy naval officers and ratings. Since Krancke had already taken after the second freighter, they were vulnerable. They pointed their guns menacingly, quickly disarmed the few men who carried weapons, and herded the 51 British prisoners, one Indian, and the 50 Dutch crewmen into a confined space, and waited for their ship to return.

At 26 knots, the Scheer rapidly overtook the 5,600-ton Stanpark. The British master, not realizing the other cargo ship had been seized, stopped his ship, put on a white uniform, and prepared to greet the expected Royal Navy boarding party. He dropped Jacob’s ladders for them. When bearded German commandos with guns and grenades clambered over the railing, an awful moment of hallucination overcame him. He quickly recovered his composure and handled the situation with British aplomb.

Captain Krancke brought the crew aboard his ship and ordered the Stanpark scuttled. Following the explosions, she settled 10 feet and stopped, apparently due to swelling cotton seeds in her cargo. The captain feared the flames and oily smoke would be visible beyond the horizon. He ordered a torpedo at 400 yards range. It missed. Krancke shook his head in disbelief.

“Try another one, Schulze,” he told the torpedo officer.

“By the way,” he asked the lookout, “where’s the [prize crew’s cutter]?”

“On the port side, sir.”

“Starboard tube, fire.”

The torpedo sprang out of its compressed air launcher on the quarter deck. Plunging about 20 feet into the water, its steering gear struck the cutter’s gunwale. How in hell, the captain wondered, did the motor launch get from port to starboard so fast?

Following the projectile’s wake, the officers and men on the bridge were horrified to see it take a U-turn and head straight back at the Scheer. The ship was not underway and nothing could be done to avoid disaster. A strange silence descended over everyone who could see the oncoming warhead.

“[I]t was just unbelievable,” Krancke later wrote. “No one could really grasp what seemed to be the obvious fact that the Scheer was about to be hit fair and square amidships by one of her own torpedoes.”

About 20 yards from the ship’s hull the torpedo nose dived and disappeared.

“You were right, Voichckovski,” Krancke told the signals officer.

“Me, sir?”

“Wasn’t it you who said the Scheer is a lucky ship.”

The third torpedo blew the Stanpark in half, and both sections went down without ceremony.

The raider returned to the Barneveld, took aboard the 102 prisoners, and sank her with her cargo of six fighter planes, 86 trucks, 1,000 tons of ammunition, and other equipment slated for the British forces in Egypt. The tally in the Gulf of Guinea was three ships in two days. And, because no raider attacks were signaled, the British did not know what had happened to the victims until they examined the Scheer’s papers after the war.

With her bunkers, magazines, refrigerators, and shelves again replenished at Point Andalusia, the pocket battleship headed southeast, rounded the Cape of Good Hope beyond the range of the South African Air Force, entered the Indian Ocean, and swept out a sterile search pattern south of Madagascar. She then headed northeast, giving the British air base at Mauritius a wide berth. She rendezvoused with the German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis and three other ships, one of them a tanker.

Atlantis Captain Bernhard Rogge, who had been raiding in the Indian Ocean for a year, told Krancke his success in the area had compelled the British to reroute cargo traffic to longer but safer coast-hugging lanes where Royal Navy protection was more efficient. He suggested that the pocket battleship sweep the zone between Mombasa (Kenya) and the northern tip of Madagascar. The Scheer took on fuel from the tanker and sailed to her next killing field off Zanzibar.

On February 20, the wireless room received the sad news that “The Floating Delicatessen” had been scuttled. She had run out of coal. The crew kept her refrigerators going with anything that was combustible—decking, doors, hatch covers, bridge timbers … even a piano went into the furnace.

The same morning, the Arado pilot spotted a northbound freighter. Krancke rang for full speed, but when they reached the estimated position of the ship the sea was empty. The pilot went up again to find her. He was barely off the catapult when the lookout called: ”Two masts at 20 degrees.” The quarry was identified as a tanker heading south. The captain wondered whether he was going to have another two-ship day, and he turned the bow straight at her. At about 10,000 yards, he began playing the Morse lamp and two guns up and one down game. Since the tanker master knew the coastal route was sailed by Royal Navy units, he felt secure flashing answers to the warship’s questions and waiting for her to close. At pointblank range, the Scheer signaled: “Heave to. Stop wireless or you will be shelled.”

aviation fuel at Rothesay Bay.

Krancke turned the raider broadside and gave the tanker a good look at her two triple turrets. He could hardly believe his eyes when he saw the gun crew running aft to man the single 4-incher. He blinked a final warning: “Don’t be foolish, captain. Call your men away from that gun. And don’t use your wireless.”

The 6,994-ton British Advocate, carrying 8,000 tons of fuel and crude oil to Cape Town, was a relatively easy capture. As the prize crew’s takeover was completed, the scout plane returned with news that the “lost” freighter was farther east than expected but still heading north. Krancke ordered the prize crew to meet the Atlantis at a point he had arranged with Rogge.

Darkness was falling when the Scheer, her radar again in a failed state, caught up to the other ship, passed her, swung across her course, and signaled, “What name?” The question was repeated several times. The answer was finally returned in an unknown language.

“Reply in English.”

“Ship, Gregorios. Country, Greece”

She is a neutral, the captain thought. A bit of a dilemma, but, what is a Greek ship doing here? He sent some boarders across who found papers indicating the 2,546-ton freighter’s itinerary was from New York to Athens with a load of Red Cross materials. Krancke did not believe that for a minute. She should have gone past Gibraltar, not around the Cape of Good Hope. His men opened a very heavy case labeled “Cotton Wool” and found machine-gun parts. They checked more cargo and came up with sheet metal, airplane tires, armored plate, and other war materials. The Gregorios crew was transferred to the Scheer, and she was scuttled the next morning.

While most of the crew was having breakfast, the pilot took the Arado up again. He returned at 9:15, having sighted a medium-size freighter. The raider stalked her until twilight, then signaled for identification. The four-letter response was coded. While the Germans worked at decrypting the ship’s name with the latest British merchant key, which had been sent to them by their intelligence service, they pretended they knew it and blinked another Morse message: “Have secret orders for you.”

The unknown ship’s master was uneasy. “What sort of orders?”

“Put about to facilitate their reception. I’ll send you a boat with instructions for your new course.”

“You have no right to stop a neutral on the high seas. This is an American ship.”

Just then the signal officer returned to the bridge. He identified the ship as the 7,178-ton Canadian Cruiser out of Halifax.

The freighter turned and ran, Krancke taking the move almost personally. “Stop at once and don’t force me to open fire. You’re behaving very suspiciously.”

“So are you,” came the immediate reply. “You’re acting like a German.”

The Scheer overtook her. Searchlights lit her from stem to stern, revealing a big Stars and Stripes on her side, the letters USA under the bridge, and an American flag being run up the stern mast.

“Is she really a neutral?” one seaman asked.

“Yeah,” said another, “like our Nordmark is the Prairie.”

The Canadian ship signaled the attack and her position, and she began to run again. The Germans started firing 1.44-inch antiaircraft guns. The freighter finally hove to. Her entire crew was found to be British and taken aboard the pocket battleship. After her protesting master was removed by force, the Canadian Cruiser was sunk with her cargo of titanium ore.

The same night, Grand Admiral Raeder informed Captain Krancke by coded message: “The Führer has been pleased to award the Knight’s Cross to you.” A second message contained instructions to return home as unobtrusively as possible by the end of March and to pick up radar crystals from a U-boat near the equator.

The airwaves filled with messages from Aden, Ceylon, Mombasa, and South Africa mounting a search for the Scheer. The pocket battleship headed southeast at flank speed. Then, reminiscent of her encounter with the Fresno City while leaving the scene of her battle with the HX 84 convoy, a lookout sighted a vessel emerging from a storm straight ahead. For the fourth time in two days, the alarm bells sounded.

The 2,542-ton Dutch coal-carrying freighter Rantau Pantjang, having picked up the Canadian Cruiser’s “RRR” transmissions and thereby aware that a raider was near, turned tail and headed into a rain curtain. She sent out her own raider and location signals. Krancke was not happy. Now the British knew his escape route. He chased the freighter through several deluges and finally stopped her with medium gunfire. Her crew was taken prisoner, and she was quickly scuttled.

Almost at once, the Scheer was spotted by an airplane, which transmitted wireless signals. The captain changed the ship’s bearing from southeast to east-by-northeast, hoping the observer was not aware of her escape direction and would be deceived by her new bearing. The plane maintained a 10-mile distance for about an hour and then left. The pocket battleship stayed her fake course for another hour in case the pilot had backed off just enough to be invisible to the Germans. As night began to fall, she returned to her original southeastern tack at top speed.

Just after midnight, a signalman was nearly knocked out of his chair by a sudden, deafening burst of nearby transmissions. It was from the heavy cruiser HMS Glasgow, whose search plane had spotted the Scheer earlier, about 25 miles away. The warships, one without radar and the other with an inoperative unit, had been passing each other in the darkness with neither of them realizing it.

The aircraft carrier Hermes and the cruiser Capetown were dispatched from Mombasa. Two heavy cruisers, the Canberra and the Shropshire, on patrol in the southern Indian Ocean, were ordered north between Madagascar and Mauritius. In the South Atlantic, three cruisers were detached from their convoys and headed around South Africa to find the Scheer.

In the morning, with no Royal Navy ships in sight, Krancke moved south between Madagascar and Mauritius. Barely into her new course, the raider ran headlong into another turn of good luck. Her radioman picked up a call from a cargo ship sailing between the two islands reporting two cruisers bearing north. The men on the bridge had never before heard the captain whistle in relief. He gratefully turned east, then southeast, and took a wide swing around Mauritius. He rounded the Cape of Good Hope, sailed almost to Point Andalusia, then stopped to scrape the hull clean of large clusters of barnacles.

On March 9, at the rendezvous site, the Nordmark filled the Scheer’s bunkers, magazines, and larders with provisions, including meat and eggs saved from the late “Floating Delicatessen.” The last of the raider’s prisoners were transferred to the supply ship.

The Scheer then meandered north unobtrusively as ordered and laid off St. Paul’s Rocks until U-124 showed up on March 16 and delivered the replacement radar crystals. In return, Krancke gave the submarine crew, whose food barely passed the test for palatability, a boatload of fresh baked rolls and cakes, corned beef, and eggs.

With her radar now in working order, the pocket battleship headed for the Denmark Strait. By March 25, she passed the southern tip of Greenland and swung north-by-east for the crucial passage. The next day, she entered the strait. The wind was down almost to zero; the air was cold, dry, and very transparent; visibility stretched to the horizon. Sure his ship would be observed on the breakthrough, Krancke headed for the Greenland ice pack where the sharp difference in temperature between the ice and the Gulf Stream might produce fog. The fog was there. Instead of edging along the pack, Krancke engaged in some inexplicable maneuvers—due east, due south, due west, then east-by-northeast toward the narrows.

Two days later, the Scheer encountered a snow squall, and for a while the crew depended entirely on their electronic eyes. At 7:52 am, the radar room reported: “Large object at 337 degrees, range 20,000 yards, 15 knots, course 60 degrees.”

“It’s one of their heavy cruisers,” Krancke said. “She’s probably looking for us near the ice pack, expecting us to be where the visibility is poorest.”

“She’s making for the narrows, too,” one of the officers said.

“I expect she’s not alone, probably meeting another cruiser there,” the captain said. “We’ll continue this parallel course, but we’ll raise our speed to 23 knots.”

Three hours later, the British cruiser Fiji faded then disappeared from the screen. Another cruiser, the Nigeria, was sighted in the late afternoon. The Scheer abruptly altered her course to the starboard, straight south. As she turned, a large puff of smoke rose from her funnel. The enemy lookout apparently did not spot it. In any case, it seemed none of the Royal Navy cruisers were fitted with radar.

At 6:30 pm, just after the pocket battleship renewed her setting to the narrows at full speed, an aggravating report came to the bridge: “Radar out of order.” This was a serious loss with enemy patrols in the area. The cause was soon found to be moisture condensation. It would be easy enough to fix but would take several hours.

A heavy cruiser was sighted about an hour later as a night shadow through the fine optics of the torpedo sighting scope. A starboard turn placed them only 8,000 yards away. Luckily, the night was a couple of hours old, and the British, whose visual acuity had not been heads up all day, sailed blithely on. One of their crewmen committed the cardinal sin of flashing a match or a cigarette lighter on deck. The momentary flare gave the Germans an exact range.

The Scheer could take her out fairly quickly, but Scapa Flow’s 30-knot battlecruisers with their 15-inch guns were less than 1,000 miles away—near enough to intercept the raider’s flight home. RAF bombers based in Iceland were within range. So, in spite of the temptation to go after the cruiser, Krancke ordered a turn to port and again made for the narrows. At 3 am, on March 28, they broke out.

With her radar working again, the pocket battleship cut through the Arctic seas as fast as she could go. No more spikes on the screen. No more distant masts or shadowy shapes.

It was an auspicious day, April 1, when she docked in Kiel after her 46,419-mile cruise, with 17 enemy ships sunk or captured and the Royal Navy and British shipping schedules thrown out of kilter at least three times. It was her eighth birthday. She had been launched with the words, “Serve your Fatherland loyally and may good luck go with you.” Fate had certainly favored her, except for the less than triumphant action against the Jervis Bay and her convoy.

The spruced up Admiral Scheer and her 1,300 officers and crew, wearing their best uniforms, piped Grand Admiral Raeder aboard. After his inspection, Raeder announced that Iron Crosses would go to the entire ship’s company. Krancke later was told he was promoted to rear admiral.

Three days later, British bombers attacked Kiel harbor. The Scheer’s antiaircraft gunners shot down two of them. Asked what their main target was, one of the captured fliers said: “Your bloody pocket battleship, of course. What else?”

The remainder of the Admiral Scheer’s career turned out to be little more than a fizzle. While she was getting a thorough overhaul in Kiel between April 15 and July 1, the new pride of the Kriegsmarine, the 45,000-ton battleship Bismarck, probably the most formidable battleship in the world at the time, was sunk on her commerce-raiding debut by a Royal Navy task force. Two weeks later, the Scheer’s luckless sister ship Lutzow was disabled by a torpedo bomber.

After the Bismarck and Lutzow calamities, Germany’s top admirals, influenced by Hitler’s naval anxiety, treated what was left of their surface fleet as if it were in a long-term care facility. The Scheer’s next raiding cruise was canceled. From then until near the end of the war, her experience resembled that of the Lutzow, except her luck remained as good as her sister’s was bad. That is, until the night of April 9, 1945.

At 10:30 pm, the first of 600 Allied bombers began dropping their loads over Kiel. The pocket battleship, now as defenseless as her raiding victims in 1940 and 1941 had been, was hit eight minutes later. This time the bomb exploded. More bombs tore holes in her starboard side and put her command and lighting systems out of commission. She listed 16 degrees away from the dock. By 10:45, further hits and near misses nearly doubled her list to 28 degrees.

An abandon ship order was sounded. Men climbed through smoke-and flame-filled spaces, up strangely tilted companionways, and through portholes. Due to electrical failure, many of the skeleton crew did not hear the order. Fifteen crewmen were killed by explosions, fire, asphyxiation, sliding machinery and other heavy equipment, and drowning. A few minutes later, the ship capsized in about 50 feet of water.

After the war, under British supervision, valuable metals, gun housings, and turrets were removed, and the mangled torso was covered over with rubble. In 1950, the remains of the magnificent, innovative Admiral Scheer became the foundation for a British-built parking lot.

Ralph Segman is co-author of If The Gods Are Good: The Epic Sacrifice of HMS Jervis Bay, co-authored by the late Gerald L. Duskin. Segman is a retired journalist and has served in the U.S. Army and the U.S. Maritime Service.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments