By John W. Osborn, Jr.

One of World War II’s longest, least known guerrilla resistance campaigns was fought in the depths of the jungle covering 80 percent of Malaya’s 50,850 square miles; in it the most unlikely of friendships would develop, leading to a remarkable meeting, then parting, a decade later.

In 1941, rubber and tin made Malaya the richest colony of the British Empire. Some 30,000 colonials lived and lorded over five million people, half native Malay, almost 40 percent Chinese, the remainder Indian. That white-suit world author W. Somerset Maugham depicted and dissected in The Letter was to be obliterated by the Japanese invasion the day after Pearl Harbor, and the British were forced to turn to a specialized brand of warfare they were preparing to export, never expecting to employ it on their own doorstep.

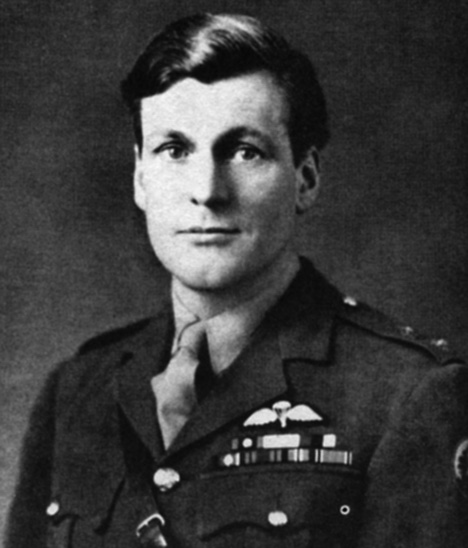

Four months earlier, the Special Operations Executive (SOE) had established Number 101 Special Training School in Singapore to train agents to lead guerrilla warfare throughout Southeast Asia; among its staff was Fredrick Spencer Chapman, a well-known explorer and author. At the start of 1942, he was sent into the interior for what was intended to be a quick reconnaissance. It would instead become one of the longest personal ordeals and adventures of World War II.

Neither the Arctic nor the Himalayas could prepare Spencer Chapman for what he would face. “I was now to learn that navigation in the thick mountainous jungle is the most difficult in the world,” he would later write. “For the first time I realized the terrifying vastness of the Malayan jungle.”

In the years to come, he would be repeatedly hunted and evade capture, lose 60 pounds, need 12 days to cover all of 10 miles, was wounded twice, suffered chronic malaria, pneumonia, and other diseases, and once suddenly remembered he had forgotten his daily diary entry only to be told he had been in a coma for 17 days!

In the end, in the words, which became the title of the classic memoir he published in 1952, Spencer Chapman realized, “The truth is that the jungle is neutral. It provides any amount of fresh water, and unlimited cover for friend and foe alike—an armed neutrality, if you like, but neutrality nevertheless. It is the attitude of mind which determines whether you go under or survive.”

Instead of reconnoitering, Spencer Chapman, like a tropical Lawrence of Arabia, rampaged through the jungle blowing bridges, ambushing, derailing trains. “What boy has not longed to blow up trains? What man too; especially if he had read Seven Pillars of Wisdom?” he would jauntily comment years later.

The Japanese became convinced that 300 Australians were involved and sent out 2,000 soldiers to search for the enemy troops; in another Lawrence-esque touch, Spencer Chapman, dressed and skin darkened like an Indian laborer, met one. “As I bowed low,” he would write, “I pressed my elbow reassuringly against the butt of my .38 which I could have drawn at the least sign of danger.”

But soon the fall of Singapore would leave him alone and presumed dead by the outside world, so he quickly had to turn for survival to the most improbable ally that a colonialist could possibly have.

Ten days after Pearl Harbor Spencer Chapman and another British officer had met in a dark back-alley room in Singapore with the mysterious head of the 40,000-member Malayan Communist Party, Loi Tek, who added to the secrecy of the affair by wearing a hood.

They agreed to prepare the communists to help resist the Japanese, and so 200 were given quick training at 101 School, then sent into the jungle. They formed the nucleus of what eventually became the 10,000-strong Malayan Peoples’ Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), supported by a civilian branch, the Malayan Peoples’ Anti-Japanese Union (MPAJU), sending in food, medicine, arms, and intelligence.

Spencer Chapman reached the MJAJA in March 1942 and spent the next three years with them. “This was a very happy Robinson-Crusoe-like existence,” he remembered, though admitting, “Once I had thrown in my lot with the guerrillas, I was virtually their prisoner and lost all freedom of movement.”

Divided into eight regional commands across Malaya, the MPAJA launched hit-and-run raids and sabotage with indiscriminate Japanese reprisals killing thousands. A Chinese communist, Ong Bonn Hua, who had joined the party at only age 15 in 1940 and soon became known as Chin Peng, undertook dangerous clandestine missions to organize resistance cells, deliver orders, and gather information; he would one day be the most hunted man in Malaya, but not by the Japanese.

The communists, however, suffered from a shortage of arms, inadequate training that Spencer Chapman struggled to improve, preoccupation with indoctrination, little support from the Malayan and Indian communities (despite the inclusive-sounding names the MCP, MPAJA, and MPAJU were all over 90 percent Chinese), and a command structure so centralized that units waited weeks, even months, for authorization to launch an attack.

The resistance suffered a further blow when a meeting of top party and guerrilla leaders at the Batu Caves in September 1942 was raided by the Japanese, with all of them captured and later beheaded. Fortunately for him, suspiciously to others, Loi Tek had been absent—a flat tire, so he said.

In Ceylon the SOE’s local branch, Force 136, was preparing to make common cause with the MPAJA. Concerns had been expressed regarding the group’s communist bent, but the Supreme Allied Commander, Lord Louis Mountbatten, brushed them aside saying, “I confidently believe that coordinated action by the MAAJA, accompanied by British liaison officers, will be the instrument of saving the lives of many of our men and hastening the eviction of the Japanese.”

Major John Davis of Force 136 had been a policeman in Malaya who sailed a Chinese junk to Ceylon after the surrender of Singapore. “The only way to get back to Malaya was by submarine,” he recalled decades later in an interview. “So I found myself with five stalwart Chinese preparing to land on the Malayan coast. The submarine dropped us about five miles from shore and we went off in canoes. We had one slight alarm on the way when we were surrounded by motor boats and I thought, ‘My God, the Jap patrol boats,’ but then the penny dropped: of course they were the local fishing boats going out. And as we neared the shore after an hour or so, the lovely warm spicy smell of the Malayan coast and the swishing of the jungle trees almost overwhelmed one and we didn’t think anymore of being 2,000 miles from our friends, we were just coming home.”

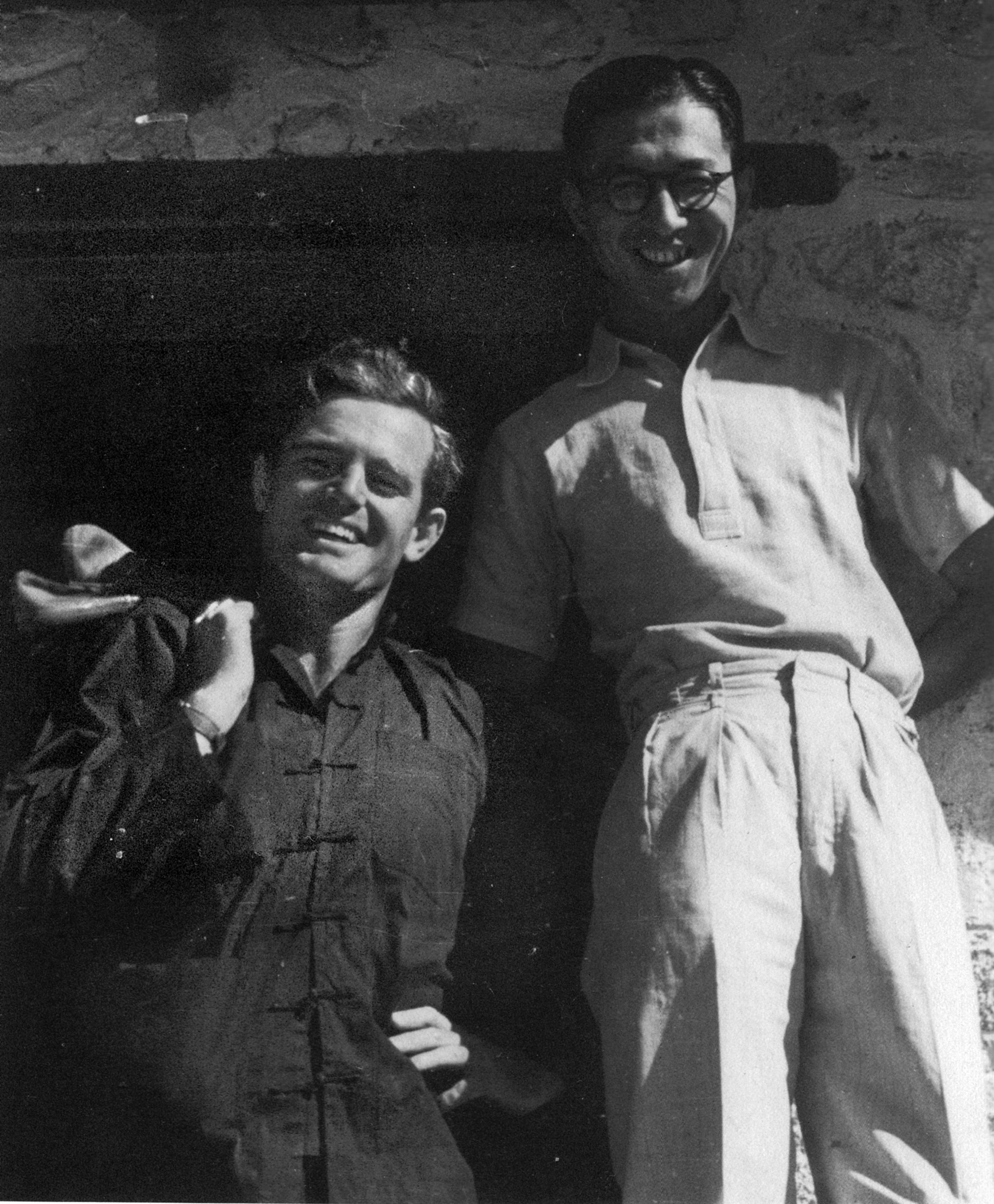

Davis landed along Malaya’s west coast on August 4, 1943, and then was led to the communist headquarters in the interior. He met Chin Peng, was as impressed with him as Spencer Chapman had been, and a genuine friendship grew between the colonial cop and the communist. “Quiet character with incisive brain and unusual ability. Very likeable … in fact almost like a British officer,” Davis would say.

Loi Tek and Davis wrote out an alliance on a page torn from a school exercise book. “The deal was that the communists would obey Allied instruction in fighting the Japanese and on the British side we should supply arms, medicines, and personnel for training and liaison,” Davis described it.

Following through on the agreement was difficult. The radio Davis had brought was too weak, and he was unable to make contact with Ceylon. Spencer Chapman was also isolated from the war—in far more dangerous circumstances.

On a trek to other guerrilla camps he ran into a Japanese sentry and was at last taken prisoner. He was marched into camp and then put into a tent with a Japanese sergeant. “I waited until one sentry was out of sight, the other at the far end of his beat, and the N.C.O. not actually looking at me,” he recalled later. “Then in one movement I thrust myself violently through the opening at the bottom of the canvas. I heard a ‘ping’ as a peg gave way or a rope broke, and a sudden guttural gasp from the N.C.O.—and I was out in the jungle.”

Spencer Chapman managed to evade his pursuers, then made his way back, hidden by villagers, down once more with malaria. He finally reached safety 103 days, on July 25, 1944.

Parts for a new radio for Davis and a generator to run it had to be slowly smuggled in one at a time, then painstakingly assembled and reassembled. Finally, powered by pedal, radio contact between Davis and Force 136 in Ceylon was made on February 1, 1945.

The British went on to airdrop almost 100 tons of arms and supplies, but the communists could not find all of it—or so they said. In addition, 88 British officers were parachuted in or landed by sea. Going the other way at the end of his long ordeal was Fredrick Spencer Chapman. “As I trudged silently in my rubber shoes along the hard-beaten track, I felt an almost breathless excitement at the prospect of what lay ahead—a prospect I hardly dared to contemplate in the last three years,” he would write. “As my thoughts went forward to the submarine, to Ceylon, to India, and perhaps to England, I realized that I had sometimes been very, very homesick.”

Spencer Chapman departed on the night of May 13, 1945. He had planned to return to help the British landing scheduled for November 1945, but Hiroshima happened instead. Determined to still be at the finish he ignored the advice of a pretty intelligence officer to make his first-ever parachute jump to assist in disarming the Japanese.

Later Spencer Chapman married the intelligence officer. Yet for months back in England he admitted, “If there were any loud noise in the night, such as a car backfiring, before I was even awake I would be out of bed and fumbling for my bundle of possessions, ready to rush away into the jungle.” His adventurous, action-filled life would become the restricted one of a schoolmaster, and in 1973 he committed suicide.

The communists used the vacuum of authority between the Japanese collapse and the British return to Malaya to murder hundreds of potential opponents as alleged collaborators, seize arms from the Japanese, and set up local Red regimes. Hardliners wanted to fight the British immediately, but Loi Tek vetoed that, and in December 1945, the MPAJA was disbanded, its fighters paid off with cash.

In the end the communists had killed only a few hundred Japanese and caused at most minor damage to the occupation. Still, the British honored the communists, with Chin Peng decorated and marching in the 1945 victory parade in London.

However, Chin Peng had warned a British officer, “You must realize that our ultimate aims are very different from yours.”

He and other communists were soon working to undermine Malaya’s recovery, leading hundreds of strikes by the tin and rubber workers. In response to suggestions the communists be arrested, a colonial official expressed the common view: “They had fought on our side…. It would not be public school.”

The British were going to be taught very differently. In March 1947, Loi Tek vanished with the party’s entire treasury. It turned out he had been a British agent all along and had betrayed the party at the Batu Caves to the Japanese. Chin Peng took over, and in June 1948 made the fateful move from subversion to open rebellion, telling the party, “We are not afraid of a protracted war. We seek the strategy of protracted war.”

It turned out to be longer than even he expected. The Emergency, as it came to be known, was declared over and won by a newly independent Malaya in 1960, but Chin Peng held out deep in the jungle all the way to 1989, when he finally signed a peace agreement, then headed to exile in China. Trying to excuse and justify himself, he argued, “I was young, in a very different age that demanded very different approaches…. You only became a terrorist when you killed against British interests.”

By the end of 1955, though, Chin Peng knew that he had lost and moved for peace talks. So on a December morning an old wartime comrade waited on a hilltop near the Thai border to guide him to the talks and guarantee his safety.

He was John Davis. “The thoughts of the past—of the good times Chin Peng and I had together—kept racing through my mind,” Davis recalled.

When Chin Peng appeared, he and Davis met with smiles and a happy handshake. At the truce site separate tents had been put up for them, but without a second’s hesitation they shared one—just like the old days.

Scheduled to last three days, the talks collapsed after two, with Chin Peng defiantly vowing to fight on; then he and Davis talked in their tent until dawn. “We got a considerable amount of our old companionship coming back,” said Davis. Despite everything, they still considered themselves friends.

A few hours later John Davis walked Chin Peng back into the jungle for what each knew would be their last time together. “Rather nice,” Davis remembered fondly in an interview three decades later, “rather like the old days with him.

“He stopped and said, ‘Well, thank you very much, that’s enough, we’ll go on now…. I’ll send a couple of my men to see you safe back.’

“I was able then to say to him: ‘You don’t think that I need to be escorted in our jungle, do you?’

“He laughed and said, ‘No, not really, I don’t think so.’ We shook hands, quite friendly.

“I turned back, wandered back to camp.

“And that,” Davis concluded with genuine regret in his voice, “was the last I’ve ever seen of him.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments