By Robert L. Durham

A North Korean column consisting of tanks and infantry advanced along a road at dawn on September 17, 1950, to attack the Marines at Ascom City between Inchon and Seoul. Some of the communist riflemen rode atop the tanks, while others trudged along beside and behind them.

An advance platoon of the 5th Marine Regiment led by 2nd Lt. Lee R. Howard lay in ambush, waiting for them to enter the kill zone. When the North Koreans came in range, the Marines opened fire from the hills along the road, assailing the tanks and infantry with recoilless rifles, bazookas, machine guns, and rifles.

A platoon of five Pershing tanks deployed in support swung into action. They pumped high-velocity, armor-piercing rounds into the enemy T-34s. When it was all over, the six enemy tanks were in flames and the ground was blanketed with 200 dead North Korean infantrymen. The Marine ambush, which appeared to have wiped out the entire enemy force, was an example of the skill and tenacity of the Marines who spearheaded the United Nations’ amphibious invasion at Inchon that had begun two days earlier.

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) invaded the Republic of Korea (South Korea) on June 25, 1950. Just three days later, the North Korean People’s Army captured the South Korean capital at Seoul. The Korean War had begun, and the advantage lay with the invading communist forces.

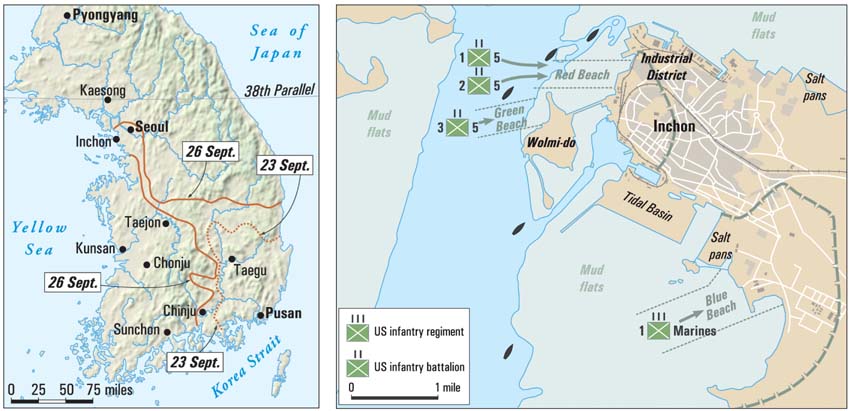

General Douglas MacArthur, Commander-in-Chief, Far East, began planning for an amphibious landing to reverse the tide of battle in South Korea’s favor. His experience with island hopping in the Pacific Theater during World War II had convinced him of the importance of amphibious operations, and he believed that a landing at the port city of Inchon would enable United Nations’ forces to sever the Korean People’s Army’s lines of supply and communication.

The planned operation was “an amphibious landing of a two-division corps in the rear of enemy lines,” he radioed the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon. “The alternative is a frontal attack which can only result in a protracted and expensive campaign.”

Inchon lay just 16 miles from Seoul. MacArthur believed that United Nations forces would be able to easily liberate Seoul if they were to land at Inchon. The code name for the operation was Chromite. MacArthur initially proposed that the landing occur on July 22; however, he was forced to push back the date because U.S. and South Korean forces were unable to stop the rapid southward advance of North Korean forces. Eventually, the U.S. Eighth Army and South Korean military forces succeeded in halting the North Koreans on August 4 at the defensive perimeter they had established to protect the port city of Pusan in the southeastern corner of South Korea.

On August 23, MacArthur conferred in Tokyo with two members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Forrest Sherman and General J. Lawton Collins, who had been dispatched from Washington, D.C., to discuss MacArthur’s risky plan with the general in person. The meeting began with Collins and Sherman trying to dissuade MacArthur from landing at Inchon. Instead, they recommended the troops come ashore at Kunsan, 100 miles south of Inchon. MacArthur stood his ground.

“The enemy commander will reason that no one would be so brash as to make such an attempt,” MacArthur told them. “Surprise is the most vital element for success in war.” He also added that the amphibious landing was the best strategic tool they had at the time. “To employ it properly, we must strike hard and deep.” He dismissed the notion of landing at Kunsan; it would be a partial envelopment that would not allow him to achieve the goal of severing the enemy’s supply and communication lines. Lastly, he said that a landing at Kunsan would prolong the “savage sacrifice” being made at Pusan, with no hope of reversing the stalemate. Although they still had reservations, Sherman and Collins backed MacArthur.

MacArthur believed that the North Koreans had deployed their best troops against the Pusan perimeter. He suspected that North Korean military leaders had left second-rate troops behind to garrison Inchon and Seoul. MacArthur received permission in August to establish the U.S. Army’s X Corps to conduct the amphibious landing at Inchon. He selected Maj. Gen. Edward Almond on August 26 to lead the X Corps landing operation; Major General Oliver Smith would lead the three Marine regiments participating in the invasion on the ground.

MacArthur planned for the troops landing at Inchon to thrust northeast and seize Seoul. “I was now finally ready for the last great stroke to bring my plan to fruition,” he wrote in his memoirs after the war. “[It was] a turning movement deep into the flank and rear of the enemy that would sever his supply lines and encircle all of his forces north of Seoul.”

Meanwhile, Lt. Gen. Walton Walker’s Eighth Army, bottled up in the Pusan perimeter, would break out and march north to link up with Almond’s X Corps. The X Corps would be the anvil, and the Eighth Army would be the hammer; the two forces would crush the North Korean Army between them.

The troops slated for Operation Chromite included the U.S. 1st Marine Division, 1st Korean Marine Corps, and the U.S. Army’s 7th Infantry Division. The 5th Marine Regiment would ship out from Pusan, the 1st Marines would come from Japan, and the 7th Marines would steam for Inchon from the Mediterranean.

Two hundred and sixty-one ships from seven nations formed Vice Admiral Arthur Struble’s Joint Task Force 7, which would transport the troops for the amphibious landing. The joint task force comprised four task forces: Fast Carrier Task Force 77, Blockade and Covering Task Force 91, Patrol and Reconnaissance Task Force 99, and Invasion Task Force 90.

The date also depended on the tide tables at Inchon. Inchon had no beaches, only mudflats in front of 16-foot-high seawalls. During low tide, the mudflats extended as much as 1,200 feet from the seawalls in some places. The tides had to be high enough to allow the landing craft to navigate over the mudflats and reach the seawalls. Some World War II-era landing craft required 23 feet of water to clear the mudflats; the landing ships known as LSTs required a depth of 29 feet. A favorable window of time occurred just once a month, over a period of three or four days. MacArthur and his senior planners settled on September 15 for D-Day. This meant that the 7th Marine Regiment would not arrive until a week after the invasion was underway.

At the end of August, Pusan and the Japanese ports of Kobe, Sasebo, and Yokohama began preparations for the Inchon amphibious operations. In order to reach Inchon by September 15, the LSTs needed to leave Kobe by September 10. The transports and cargo ships had to leave on September 12. Japanese crews manned 37 of the 47 LSTs in the Marine convoy.

On September 11, the 1st Marine Regiment steamed out of Kobe, and the Army’s 7th Infantry Division departed from Yokohama. The 5th Marine Regiment embarked from Pusan the following day. Marine tactical air strikes began on September 4 and continued intermittently until D-Day. Napalm strikes burned off much of the tree cover on Wolmi-do Island, one of the D-Day objectives.

On the morning of September 13, five destroyers began their preparatory bombardment. Five enemy 75mm mortars, which were situated in heavily bunkered emplacements on Wolmi-do, returned fire. Mortar rounds struck the destroyer Collett nine times, and she suffered considerable damage but no casualties.

The destroyers withdrew in the early afternoon and three cruisers took their place, pummeling North Korean positions for an hour and a half, followed by a heavy air strike on Wolmi-do by aircraft from Task Force 77. Afterward, the cruisers resumed their fire for a brief period. On September 14, Task Force 77 carried out more air strikes, followed by additional bombardments from the cruisers and destroyers. This time, the North Koreans did not return fire. It appeared that their batteries had been silenced by the combination of air strikes and naval bombardment.

United Nations forces had to contend with two harbor islands: Wolmi-do and Sowolmi-do. They scheduled a battalion-sized assault on Wolmi-do Island, which lies west of Inchon, during the early-morning high tide. The 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines would land at Wolmi-do at 6:30 am. The main landings at Inchon were scheduled to occur in the late afternoon at high tide. Three landing beaches were selected: Green Beach at Wolmi-do, Red Beach in the seawall-dock area of Inchon, and Blue Beach in the mudflat area south of the city. The 1st and 5th Battalions would attack Inchon at the high tide that came at 5:30 am.

MacArthur and his planners had selected September 15 as D-Day. The Marines came ashore at Wolmi-do Island at 6:33 am, landing unopposed on a bathing beach on the north side of the island. The first units ashore, G and H Companies, advanced rapidly across the island. Marine Corsairs strafed the island ahead of their movement with machine-gun rounds. The leathernecks met little resistance, most of the North Koreans preferring surrender to death. The Marines soon controlled the highest point on the island, known as Radio Hill, on the crest of which Sergeant Alvin E. Smith raised an American flag.

When the reserve force, I Company, landed, it ran into a North Korean stronghold that H Company had inadvertently bypassed: the North Koreans held fortified caves on the side of the island facing Inchon. They ignored all efforts to get them to surrender, occasionally firing their weapons and hurling hand grenades at the Americans. Marine commanders issued orders for M26 Pershing tanks and Marine riflemen to pin down the enemy while a tank outfitted with bulldozer blades worked to seal the caves.

After just 90 minutes of fighting, the Marines reported to MacArthur that they had secured the island. MacArthur then sent a message to Struble, who was aboard the Rochester. “The Navy and Marines have never shone more brightly than this morning,” he informed Struble.

Sowolmi-do, the battalion’s final objective, contained a lighthouse connected to Wolmi-do by a 750-yard causeway. Shortly before 10:00 am, two hours after the attack on Wolmi-do had ended, G Company began its assault on Sowolmi-do. Company commander 1st Lt. Robert Bohn selected a rifle squad, machine guns, and a tank section for the assault. When the Marine assault force arrived at the causeway entrance to Sowolmi-do, it was met with heavy rifle and machine-gun fire from the North Koreans. An enemy platoon on the islet had decided to defend their positions.

Marine battalion commander Lt. Col. Robert Taplett called in an air strike to soften up the enemy position. After Corsairs dropped napalm canisters on the target, the assault force moved cautiously down the causeway with the tanks leading the way. The mortar platoon of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines struck the communist position with 81mm shells, greatly reducing enemy gunfire. The Marine riflemen spread out and closed with the enemy, covered by fire from the tanks. The assault force was quickly able to suppress the enemy machine guns, using a flamethrower and grenades to knock out the remaining enemy troops. The Americans had killed 108 North Koreans and taken 136 prisoners in their assault on the two islands.

Prisoner interrogations revealed that the original number of North Korean defenders on both islands was 400. This meant that the remaining North Koreans had been buried in the rubble and in collapsed caves on the islands. Brigadier General Edward A. Craig landed on Wolmi-do that night and set up his brigade command post. Taplett asked for permission to attack Inchon from the causeway, but when Craig forwarded Taplett’s request to MacArthur, the commander-in-chief denied it.

The plan for the attack on Inchon proper called for the 1st and 2nd battalions of the 5th Marine Regiment to assault the seawall on Red Beach north of the Wolmi-do causeway. The battalions would then proceed into the heavily built-up area of the Inchon waterfront. The 1st Battalion would land on the left to assault Cemetery Hill and the northern half of Observatory Hill, and the 2nd Battalion would manuever to capture the southern half of Observatory Hill.

While the 5th Marine Regiment focused on capturing the high ground, the 1st Marine Regiment would attack at Blue Beach south of Inchon, which faced a suburban manufacturing area. The Marines hoped they would be able to use their amphibious tractors, since the seawalls did not run the full length of the landing site.

The assaults on Red Beach and Blue Beach occurred simultaneously. To prepare Red Beach for the landing, four cruisers and six destroyers fired on the seaport for three hours, obliterating the targets and starting fires that blazed across Inchon. The Marines then hit them with two fighter squadrons and three squadrons of U.S. Navy Skyraiders, which alternated their attacks with a naval bombardment. In addition, Task Force 77 kept a dozen planes in the air for deep-support missions, suspending enemy activity up to a distance of 25 miles. Before the assault began, rain squalls and the smoke from the bombardments decreased visibility.

The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 5th Marines swarmed down cargo nets to the landing craft for the five-mile trip to the landing sites. The fire of the cruisers and destroyers increased as the landing craft drew nearer. In the late afternoon, the naval bombardment ended, and the rocket ships went into action. During the next 20 minutes, 6,000 rockets struck the seaport. When the landing craft reached the midpoint, the rocket ships ceased their fire, and the Skyraiders made final strikes until the landing craft were 30 yards from the seawall.

The 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines on Wolmi-do supported the landings with machine guns, mortars, and tank fire. Engineers cleared antitank mines from the causeway so that it could be used immediately after the landings.

The first wave contained eight landing craft. The seawall rose four feet above the ramps of the landing craft. Some of the ships landed where the bombardment had blasted gaps in the wall, so the men were able to rush inland easily. Each of the landing craft carried two aluminum ladders. Where no gaps existed, the landing craft struck the seawall and the Marines tossed grenades over it. The leading Marines then used the ladders to mount the walls and then hung cargo nets over them.

This allowed the Marines who followed to mount and clear the wall more quickly. The Marines of the 2nd Battalion, who spearheaded the attack, suffered no casualties as they rushed inland to cover the second and third waves. The 1st Battalion received heavy fire on its left flank and submachine-gun fire from a bunker. The enemy immediately cut down several Marines from Boat Two and pinned down the rest before they could advance more than a few yards. Boat Three found a gap in the seawall. A machine gun in a pillbox covered the gap, but the leathernecks received no fire from the gun. The Marines swarmed through the breach and up the waterfront. Another squad with a 3.5-inch mortar joined them from Boat Four.

A long trench paralleled the seawall, but the Marines found it unoccupied. The Marines hurled grenades into a pillbox as a precautionary measure, and six injured North Koreans emerged from the it and were taken captive.

A vertical cliff formed the seaward side of Cemetery Hill. Second Lieutenant Francis W. Muetzel, rather than trying to scale the cliff, moved his troops up a road to the Asahi Brewery, which they reached unchallenged.

The North Koreans kept the 1st Platoon of the 1st Battalion pinned down as the rest of the battalion came up behind them. The men all squeezed into the same crowded area, and casualties began to mount. Two Marines attacked with flamethrowers, but the North Koreans killed them both.

Alighting from his landing craft, 1st Lt. Baldomero Lopez rushed forward and blasted the first enemy pillbox with a grenade. As he advanced to the second with a live grenade in his hand, he received a serious wound under the right arm from a burst of machine-gun fire. Unable to throw the grenade due to his wound, he threw himself on it, shielding his fellow Marines from the explosion. For his act of valor, Lopez posthumously received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Captain John Stevens landed in the same congested area and put his executive officer, 1st Lt. Fred Eubanks, in charge. “Take over on the left and get them organized and moving,” Stevens ordered. Since the North Koreans still held Cemetery Hill, the Marines had no time to waste. Additional waves would be arriving in the next half hour. Stevens radioed Muetzel to bring his platoon back from the brewery to help in the assault.

Muetzel formed his men into a column and started back to the landing site, and it was then that he detected an excellent approach to the top of Cemetery Hill. Muetzel immediately launched an attack up the hill, and the men moved quickly up the incline, flushing out a dozen enemy soldiers who promptly surrendered. When they reached the top of the hill, they saw the hilltop alive with enemy infantry crews from the 226th Mortar Company. The heavy bombardment had stunned them, and almost all surrendered. The Marines captured the top of Cemetery Hill in just 15 minutes without sustaining any casualties.

During the attack on Cemetery Hill, Eubanks had taken a position on the left. He led a grenade attack on the North Korean emplacement, then ordered a flamethrower operator to finish it off. The 1st and 3rd platoons linked up with the 2nd platoon at 5:55 PM. Stevens fired an amber star cluster to signal that the Marines had secured Cemetery Hill. The half-hour fight cost the Marines eight killed and 28 wounded.

The North Koreans controlled all but the lower slope of another main objective, Observatory Hill, which rose 200 feet above the Marine position. Company C of 1st Battalion had orders to take the north side of the hill, while D Company of 2nd Battalion would capture the south side. Elements of both companies landed on the wrong beaches, though. As more waves landed, the congestion and confusion became worse.

The North Koreans on Observatory Hill recovered from the shock of the bombardment enough to set up machine guns. Other enemy soldiers established mortar positions in the town. Eight LSTs came down the river carrying the last wave of American forces. They started receiving machine-gun and mortar fire as soon as they came within range. Leading the way, LST 859 responded by opening with 20mm and 40mm cannon on Cemetery Hill, Observatory Hill, and the right flank of the beach. The next two ships in the column also received machine-gun and mortar fire. The crews of both vessels reacted by firing on Cemetery and Observatory Hills. Enemy machine guns hit the fourth LST, igniting a fire near one of the ammunition trucks being transported. Sailors and Marines on board quickly put out the fire. This ship did not return fire, the captain having received orders not to do so.

Friendly fire from the LSTs on the river drove Lieutenant Muetzel’s platoon from the summit of Cemetery Hill, forcing the Marines to take cover on the north slope of the hill. A North Korean machine gun in a building on Observatory Hill then began firing on them; luckily, a 40mm round from one of the LSTs struck the building and destroyed it, killing the machine-gun crew. Muetzel’s platoon did not suffer any casualties.

Lieutenant Colonel Harold Roise’s 2nd Battalion did not manage so well. These Marines landed and started inland, but they also took friendly fire from the LSTs. His weapons company and headquarters-and-service company suffered one killed and 23 wounded. Fortunately for the attacking Marines, a large building sheltered most of the battalion.

“If it hadn’t been for the thick walls of the Nippon Flour Company, the casualties might have been worse,” Boise said afterwards. All eight of the LSTs had successfully berthed in their assigned landing sites by 7:00 PM. They ceased firing as soon as they hit the seawall and contacted the Marines on shore.

Second Lieutenant Byron L. Magness reorganized his 2nd Platoon of C Company and attacked Observatory Hill on his own volition, followed by 2nd Lt. Max A. Merritt’s 60mm mortar section. Confusion during the landing had fragmented the rest of the company at the landing site. Sergeant Max Stein led the way, taking out one machine gun single-handedly.

Observatory Hill had three separate peaks. By 6:45 PM, the provisional force had taken the saddle between the two western peaks. Lieutenant Colonel George R. Newton, commander of 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, ordered B Company to take over C Company’s mission and attack Observatory Hill’s northern side.

B Company sustained six wounded charging up the slope of Observatory Hill in the dark. They reached the top at 7:00 PM and linked up with Magness and Merritt’s provisional force. Newton radioed several hours later that the Marines had secured both Cemetery Hill and the northern half of Observatory Hill.

On the right flank of Red Beach, the 1st Platoon of E Company pushed forward along the railroad track with no resistance. The next to land, D Company, prepared to seize their objective—the southern half of Observatory Hill. Expecting no resistance, they formed a route column and marched up a street to the peak. Having carried the first summit without a fight, they assumed the second peak had been taken. They continued along the street toward the second summit, but this time, the North Koreans were waiting.

A North Korean squad entrenched on the right-hand side of the road assailed their column with machine-gun fire. The Marines took cover on the other side and exchanged small-arms fire and grenades with the North Koreans. The leathernecks suffered one killed and five wounded. The corpsman received a wound while caring for the other injured but refused to be sent to safety until he nursed and evacuated everyone else. The leathernecks succeeded in driving away the enemy just before nightfall.

The Marines had secured all objectives except the tidal basin on the extreme right flank. Lieutenant Colonel Roise reported this to Lt. Col. Raymond L. Murray, whose regimental headquarters had landed at 6:30 PM. Murray told Roise he wanted an outpost at the tidal basin if nothing else. Roise took a two-squad patrol from F Company to the tidal basin. They returned to tell him that they had encountered no enemy force. Roise ordered F Company (now less than one platoon) stationed on Observatory Hill to establish a defensive perimeter on the right flank.

By that time, it was dark. The sea current, combined with decreased visibility from the smoke, caused many of the landing craft to become disorganized. Eight LSTs, loaded with equipment to support the troops the next day, beached on the mudflats just before high tide. Three of the LSTs took incoming fire from North Korean mortars and machine guns. They fired wildly into the beach area, causing several casualties in the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Marines before they could be stopped.

Simultaneous with the assault on Red Beach, the 1st Marines attacked Blue Beach. Rain squalls and smoke completely blocked the view of the landing site. In addition to those difficulties, the 1st Marines had never operated together as a regiment before their assault on Blue Beach. There were also unanswered questions about the landing site itself: while there appeared to be a road and a drainage ditch where tracked landing vehicles could come ashore, it would take 45 minutes for the slow-moving amphibious tractors to reach land. To make matters worse, the strong current scattered many of the landing craft before they could even start for the shore.

The first wave, which consisted of LSTs escorted by Navy guide boats, included underwater demolition teams. The crews of the guide boats possessed the seamanship and compasses necessary to find the beaches through the smoke and fog. The vessels in the second wave followed close behind so that they could take advantage of the guide boats. Some amphibious tractors of the third wave became intermingled with the second wave. As a result, some of these vehicles arrived ahead of schedule. This created a significant degree of confusion.

On the left flank, the amphibious tractors transporting G Company headed for the drainage ditch. The lead tractor became stuck in the mud, blocking the other five tracked landing vehicles coming up behind. Captain George Westover ordered his men out of the tracked landing vehicles, and they sloshed their way toward a road that headed inland. While G Company tried to get inland via the drainage ditch, I Company clambered over the walls using aluminum ladders. Company C of the 1st Engineer Battalion hung cargo nets over the walls to speed up debarkations, while G Company made it ashore and seized Hill 233.

Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, the commander of the 1st Marine Regiment, landed at Blue Beach with the third wave. He sought to organize the assault battalions, which had become confused and disorganized. Supply ships also landed to resupply the troops on shore. Companies G and I cleared the beachhead. Enemy machine-gun fire, which was coming from a tower 500 yards inland, caused some casualties for I Company. Machine-gun fire from one of the tracked landing vehicles silenced it. The Marines spent the night consolidating gains and landing supplies. At that point, the leathernecks on Wolmi-do Island advanced across the causeway to reinforce the Marines that had landed at Inchon.

The Marines had to race to the next line in preparation for an assault on Kimpo Airfield. Marine aircraft were on station to support the U.S. ground troops. The pilots rolled their Corsairs over and came after the six enemy T-34 tanks with napalm and rocket salvos. They knocked out three of the tanks, with a loss of one Corsair. The damaged aircraft was struck in the air cooler by one of the North Koreans’ antiaircraft guns. A second sortie knocked out two more of the tanks. The Corsair pilots also strafed a large force of North Korean infantry who were in the open.

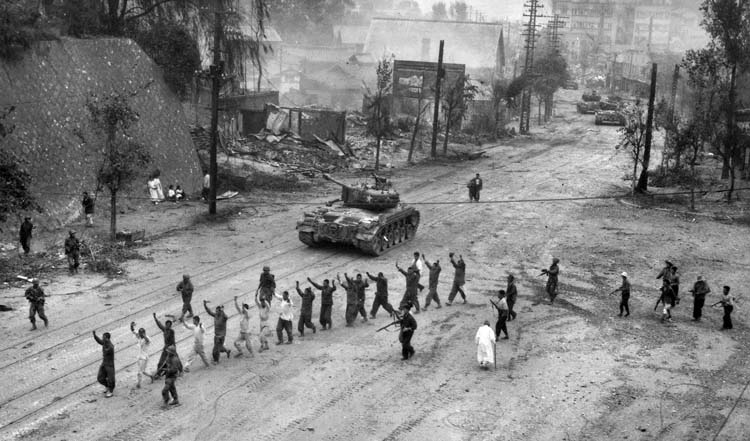

The South Korean Marines moved in to mop up any enemy still on the beachhead; they did not question very closely those they suspected of collaborating with the enemy.

The mopping-up operation was much tougher than expected. The North Koreans hid until the Marine front line had passed, and then they rose up from sewers and drains with machine guns to demoralize the reserve troops. The South Koreans killed 18 of these North Koreans who had been lying in wait.

Puller’s troops pushed inland toward a site that had once been a U.S. supply depot, Army Service Command, also known as Ascom City. The site had grown into a huge compound, almost two square miles of residential, industrial, and storage areas. Ascom would prove to be a thorn in the side of the 5th Marines.

Puller advanced on Kansong-ni, which had been used by the North Koreans for tank reconnaissance and patrol training. A tank duel unfolded between a section of Pershing tanks and three T-34s. The T-34s had only manually powered hand-crank turrets, which were no match for the hydraulically driven turrets of the Pershings. Before the enemy tanks could even take aim, the Pershings fired 20 90mm armor-piercing shells, destroying the North Korean tanks.

As the Marines advanced toward the airfield, no other North Koreans were encountered except for a few snipers; these were taken out with the usual Marine efficiency. It soon became too dark to proceed with confidence. After the successful Marine ambush of the counterattacking North Korean column at Ascom on the morning of September 17, MacArthur sought out Puller for a first-hand report on the situation. “If he wants to see me, have him come up to the front lines,” Puller is reported to have said. The septuagenarian MacArthur huffed and puffed his way to the top of the hill. Finding Puller, he told him that he had expected to find him at his command post. “That’s my CP!” responded Puller, slapping the high ground on the map. MacArthur awarded Puller the Silver Star on the spot.

Two important objectives still remained to be taken before the advance on Seoul. These were Kimpo Airfield and Seoul’s industrial suburb, Yongdungpo. Both were on the near side of the Han River. Roise’s 2nd Battalion of the 5th Marines was tasked with capturing Kimpo; the job of capturing Yongdungpo fell to Puller’s troops. The route of the ground troops was too rugged for the tanks, so the armored vehicles detoured on a road two miles to the south. The Marines did not reach their objectives before nightfall, when they set up their defensive perimeters. The 5th Marines took possession of Kimpo Airfield and its 6,000-foot runway on September 17, but they would have to defend it against determined counterattacks the following morning.

At 3:00 am on September 18, the North Koreans moved against one of the Marine positions. They only became aware that they were walking into an ambush when Sergeant Richard L. Marston jumped up and confronted them. “U.S. Marines!” he shouted, and immediately opened fire with his M-1 carbine on full automatic. The other Marines fired on the startled North Koreans with rifle and automatic weapons fire. When it was all over, 12 North Korean soldiers lay dead. The rest slipped away into the night.

The North Koreans made three more probes that night. The Marines easily dispersed all three of them, and the enemy’s morale was clearly shaken. Each time they came upon the Marines, the North Koreans barely engaged with them before retreating into the dark. The North Koreans only had a few hundred men, most having slipped away before they could organize the assaults.

The North Koreans made a more powerful attack at dawn, sending another tank column against the Marines. The forward-most Marines had no antitank weapons, and therefore had to fall back; however, the Marines ultimately defeated the North Korean armored attack with mortar fire.

Meanwhile, Puller’s Marines advanced along the Inchon-Seoul Highway to Yongdungpo on the south side of the Han River. Marine aircraft pounded Yongdungpo with bombs, rockets, and napalm before the riflemen entered the industrial town. Although the enemy parried assaults on the left and right, a column of 200 Marines managed to cross the dike on the suburb’s perimeter and enter the suburb unopposed. The Marines entrenched, because they expected the enemy to counterattack. The North Koreans did indeed attack, backed by more T-34s, and the Marines fought back tenaciously with their bazookas. The fighting in Yongdungpo ended on September 21 with the Marines in possession of the suburb.

That same day, the 7th Marines, which had sailed from the Mediterranean to reinforce the two Marine regiments already engaged, began disembarking at Inchon. They would play a significant role in the battle for Seoul.

The North Koreans launched a determined counterattack on September 20 towards Yongdungpo, with infantry backed by five tanks. Three Marine companies engaged and destroyed the North Korean thrust, killing a total of 300 enemy soldiers in the firefight.

Once Kimpo Airfield was again in friendly hands, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing commander Maj. Gen. Field Harris deployed three Marine fighter squadrons to the airstrip. On the same day, C-54 Skymaster and C-119 Flying Boxcar transports also began landing at the airfield to unload supplies for United Nations forces. The United Nations suffered 227 killed and 800 wounded in the Battle of Inchon. As for the North Koreans, they lost 1,350 troops.

The campaign for Seoul proved to be a grueling one. Unlike the rapid success at Inchon, United Nations forces would spend an entire week fighting in Seoul. The North Koreans tried to stall the U.S. offensive so that they might shift forces from the Pusan perimeter to reinforce Seoul. This strategy failed, because the U.S. troops bottled up at Pusan broke out and raced north towards Seoul. The communists had no choice but abandon Seoul and retreat north of the original boundary between the two countries.

MacArthur considered the war won, but he would not be satisfied until he advanced across the 38th parallel. In the ensuing campaign, the United Nations forces under MacArthur’s direction advanced towards the Yalu River, which was the boundary between North Korea and China. It was the advance of United Nations forces towards the Yalu River that enabled Chinese Chairman Mao Zedong to convince his people that China needed to intervene in North Korea in order to prevent a U.S. invasion of China.

Chinese and American forces clashed on November 1. United Nations forces found themselves in a precarious position as snow began falling in the mountains of North Korea. The Chinese drove back the United Nations forces in North Korea. On November 27, Chinese forces surprised Maj. Gen. Edward Almond’s X Corps at the Chosin Reservoir. In desperate fighting over the next two weeks, U.S. forces struggled to extract the troops that were isolated at the reservoir.

On the political front, MacArthur asked President Harry Truman for permission to bomb Chinese bases in Manchuria, but Truman, who vehemently opposed widening the conflict, overruled MacArthur. When MacArthur tried to undermine the president, Truman instructed the Joints Chiefs of Staff to remove him from command on the grounds that he had made public statements contradicting the administration’s policy on the war.

On April 19, 1951, MacArthur, the architect of the victory at Inchon, made a farewell address to Congress. Although many wanted him to seek the Republican nomination in 1952, he declined to actively seek it. Another great American general, Dwight D. Eisenhower, won the election in a landslide instead.