By Jean René Champion (with Marc and David Champion)

Jean René Champion (or René, as he preferred to be called) was born in 1921 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, a commune on the west side of Paris. He never knew his father, and his mother, Marcella, abandoned him to an orphanage at eight months of age. He came to America when he was eight years old and lived a hard-scrabble life during the Great Depression—riding the rails across the country as a hobo, working at such odd jobs as a cowboy and lay preacher, and spending time in Mexico living with a native tribe.

When World War II broke out, 20-year-old René, wanting to avenge the occupation of the land of his birth, made his way to England, where the 2nd French Armored Division was forming and training under Maj. Gen. Philippe Leclerc, with the purpose of one day taking part in the liberation of France.

Here is his remarkable story.

If I were given the choice of reliving just one day of my life, I would make that choice without hesitation—August 25, 1944—the day that Paris was liberated. On the morning of that great day, I drove a Free French tank [an American-made M-4 Sherman] into a Paris still held by the Germans.

Long after night had fallen on that day, I lay exhausted but unable to sleep in the still sun-warmed dust of the Jardin des Tuileries and marveled at the special brilliance of the summer stars as they shone on a free Paris.

Between that morning and that night, I had lived through one of those “once-in-a-lifetime” days and had experienced, I think, all of the emotions that are granted to man to feel, and I had known them with all the intensity of which man is capable.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

In 1941, as a 20-year-old French citizen who had been living in the U.S. since 1929, I responded to General Charles de Gaulle’s appeal to Frenchmen the world over to rally to him in England, to where, with the help of Winston Churchill, he had managed to escape from German-occupied France.

De Gaulle’s objective was to create an army of volunteers that would eventually help drive the German occupants of France back beyond their borders. He named those volunteers the “Free French” to distinguish themselves from those French units who had chosen to give their allegiance to France’s German-controlled Vichy government.

I was then living in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and traveled to the Free French Office in New York City, where I was approved as a volunteer on August 25, 1941 (exactly three years before the day of the liberation of Paris). I then I boarded a small whaler, the SS Surabaya, that joined a convoy bound for England.

Luckily, we did not encounter (to my knowledge) any German U-boats, which made a habit of attacking convoys full of Lend-Lease goods headed for Great Britain or the Soviet Union.

Three days at the Royal Patriotic School

Approximately two weeks after departing New York, we landed in Liverpool, which was under German aerial attack when we arrived. From Liverpool, I, along with a half-dozen volunteers for the Free French Navy, was sent for a brief stay to the “Royal Patriotic School” in Wandsworth Common, London.

There, the backgrounds of all travelers arriving without complete documentation (the only official paper I had was an “affidavit-in-lieu-of-passport” signed in New York by a British Consular official) were examined by members of British Military Intelligence to ensure that the new immigrant was neither an enemy spy nor saboteur.

The main building was a handsome, Victorian brick edifice three or four stories high. It had a gabled roof and towers and many large windows. Behind it was a large, charming, typically British garden, with wide walks and a great variety of well-tended plants and shrubbery. The entire compound was surrounded by a high wall.

Before the war, the Royal Patriotic School had been a school for girls, but its scholastic role had been abandoned in 1940 when London was being bombed day and night by the Germans. London children had been evacuated from the city and sent to the English countryside for safety. With the girls at the Royal Patriotic School having been likewise evacuated, the facility was then turned over to the British Intelligence Service, and its function was to provide quarters for newcomers to England while their backgrounds were investigated.

While waiting for our backgrounds to be checked, we filled our idle hours with various diversions such as chess, checkers, and bridge. There was a piano in one of the Patriotic School’s large rooms, and there were enough piano players in the group to keep the instrument occupied almost the entire day. Rare were the times when the whole building was not filled with the strains of the classics or the popular melodies of the day.

Whenever the piece being played was a popular song, men would wander in from other rooms and begin to sing in their own native tongues. One day the pianist was playing Amapola, a popular and nostalgic love song of that era. He was soon joined by a singer with a trained operatic voice, and his rich baritone filled the entire ground floor of the building.

Chess players left their chessboards and came into the piano room. Readers folded their books and came to see and sing. Card players laid down their hands and stood and raised their voices. Soon almost everyone was standing and singing, each one in his own language, each one with his own thoughts and feelings.

The cheeks of more than one were wet with tears. They were singing with their hearts, singing of the loves they had left behind, of their families, of the lands they knew and loved and were so far away from.

I, with my own tears, felt so very close to these men. In those magic moments, we were no longer strangers, but the closest and dearest of brothers. As I watched them, I couldn’t help but wonder how many of them would survive the war and find again the things they were weeping for. The knowledge that many of them would not return filled me with a profound sadness.

My stay at the Royal Patriotic School lasted three days. I spent perhaps an hour in an interview with a British officer. I was astounded at the information he had about me—my runaway days in Johnstown; my brief incarceration in a children’s correctional institution; my hoboing all over the United States under the assumed name of George Hoffman; my brief career as a lay preacher; my suicide attempt in New Mexico; my skills as an architectural draftsman; and countless other details.

I was given a clean bill of health and turned over to a Free French representative in London. After passing a cursory physical, I had my curly locks shorn, and then I signed my enlistment papers “for the duration of the war” and was advised that, as a member of the Free French Forces, I was now under sentence of death by the Vichy government of France. I must admit that I got a kick out of that—it is not just anybody who walks around with a death sentence hanging over his head.

I was issued a dress uniform (the famous British battle dress, since the Free French Forces at that time were being supplied by the British), a black beret, a British steel helmet, a gas mask, and sundry other articles of regulation attire.

New Quarters at Camberley

The next day, several other new enlistees and I were driven out to the town of Camberley, some 30 miles southwest of London, where the Free French had their principal training facility. This location was called Old Dean Camp. Upon our arrival, we were each assigned to a barrack and issued a rifle and bandolier of cartridges, a mess kit, a straw tick for our cots, and a blanket.

Unlike our comparatively luxurious quarters at the Royal Patriotic School, our barracks at Camberley were Quonset huts, or Nissen huts, as the British called them. Cold and drafty, with only a pot-belly stove for warmth, they did little to keep out the cold, wet, English weather.

Most of the men at Camberley were in their 20s and 30s. There were a few as young as 16 and some in their late 40s and early 50s. They had come from almost every corner of the world, and many had undergone considerable hardships in their efforts to join de Gaulle’s army.

French nationals had gotten to England in a variety of ways. A few were businessmen or students who happened to have been in England when France surrendered after the German invasion.

Besides French nationals, there were volunteers from many other countries. Thus, in the unit that was to become Third Company, there was a mix of Americans, Belgians, Britons, Canadians, Mexicans, Middle Easterners, North Africans, Poles, Spaniards, South Americans, and Swiss.

A larger group, who were also in England at the time of the French surrender in 1940, consisted of French soldiers who had been rescued in 1940, along with British units, from the Dunkirk pocket and from the ill-fated Allied Norwegian campaign.

Although most of these “rescuees” were repatriated, a sizeable number enlisted in the fledgling Free French army and continued to fight with the hope of eventually liberating their homeland.

For the French at Camberley who did not happen to be in England at the time of France’s surrender, their roads to England had been complicated and often difficult.

One such group consisted of French soldiers who had been in German prisoner-of-war camps and who had managed to escape from Germany and make their way to Russia.

Unfortunately for them, Russia at the time was officially an ally of Nazi Germany [before Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the U.S.S.R. in June 1941]. The Russians arrested the escaped prisoners and imprisoned them in concentration camps.

Five or six months later, when Germany betrayed its alliance by invading Russia, the French prisoners were released and sent to England. Without exception, they joined de Gaulle. At Camberley, we referred to them as les Russes—the “Russians.”

Shortly after the arrival of les Russes, two other escaped French prisoners arrived at Camberley. These two had made their way from Germany into Sweden, a neutral nation. From there they were able to get to England. They were known as “the Swedes.”

Others had made their difficult way from North Africa to England through Spain. Two of these men would later become members of my tank company. Both were Swiss nationals who had been in the French Foreign Legion in Algeria when France was defeated.

When they discovered that their commander had no intention of declaring his allegiance to General de Gaulle, they deserted and made their way across the desert to Spanish Morocco, where they were arrested and sent to the infamous Miranda concentration camp in northern Spain. There they lingered for seven months before being released to the British consul.

Spain, at the time, had declared itself a neutral nation whose Francisco Franco-led fascist government sympathized with Nazi Germany and its ally, fascist Italy. This situation did not make the transit of Frenchmen through Spain and on to England easy.

Indeed, the Free French volunteers who entered Spain knew that there was a very high probability that they would be caught by the Spanish police and would likely spend months in the infamous concentration camp at Miranda, where they would be ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-treated, and ill-cared for.

But they also knew that eventually the British Embassy in Madrid would arrange for their release and their dispatch to England. So, motivated by love of country or simply the desire for adventure—or both—they crossed into Spain, suffered the penalty of Miranda, and eventually reached Camberley. When they arrived, many were emaciated and afflicted with a variety of pulmonary and other ailments.

A few of those who came through Miranda had difficulties even before reaching Spain. That was the case with two men who later became members of my tank company. Both were Swiss nationals who had been serving in the French Foreign Legion in Algeria when France was defeated.

When they discovered that their commander had no intention of declaring his company’s allegiance to General de Gaulle, they deserted and made their way across the desert to Spanish Morocco, where they were arrested and sent to Miranda.

As deserters of the Legion, the trek from their desert post in Algeria was undertaken in full knowledge that there was a price on their heads—25 francs if caught and returned alive, 50 francs if delivered dead.

Other men had come to England directly from occupied France, also in great peril. Some had made the trip by sailing small boats through the German seaborne patrols off the French coast and across the rough and dangerous waters of the English Channel.

Several others were amateur pilots who managed to make the journey in their own airplanes. One of these pilots had even gone so far as to construct his own aircraft especially for the occasion. Needless to say, some of these patriots lost their lives in their gallant attempts.

Regardless of the means by which they came to England, many of the French nationals felt it necessary to adopt assumed names; they were afraid that the Vichy authorities in France would take reprisals against their families if it were discovered that they had joined de Gaulle.

Four of the “foreigners” in my company were referred to as les américains; I was one of them. My nationality was still French, but my home was in America. Henri Jolivet, another américain like me, had been born in France of French parents and had come to the U.S. as a child. His parents were naturalized Americans, and his home was in Staten Island.

“Red” Jourdain came from Chicago. He was rather taciturn, and little was known about him. In the minds of many of our French colleagues, the word “Chicago” conjured up movie-inspired visions of Al Capone and his band of gangsters, so that some of them suspected that Red had been in the employ of the Mob.

Maurice Gator, the fourth américain, was not American in any sense of the word. He was a native-born Parisian but had lived in New York for about a year before joining the Free French and, in the eyes of our French colleagues, that qualified him as an américain. Before he changed his last name, it was Introligator.

Our categorization as “Americans” was in no way meant to be derogatory. On the contrary, our French brothers-in-arms knew little about the U.S. except for what they had seen in the movies, and what they had seen generally had impressed them favorably. As américains, we were often asked questions about what life was like in the U.S. and were listened to almost with the awe of children listening to a fairy tale.

Gator, Jolivet, and I became close friends. Jourdain, more of a loner, remained on the periphery of our little group. I alone survived the war; Gator was killed in Normandy, Jolivet in Alsace. Jourdain survived the war in Europe but was killed in combat in Indochina after the European war had ended. They were good buddies and, although more than 60 years have passed, I grieve for them often.

That fact that, whether French or foreign, we had each risked or given up much to join the Free French engendered among all of us in Camberley a profound mutual affection and respect. We were not just volunteers: we all shared a vision of a free France, we had all demonstrated the toughness to do whatever was required to rally to de Gaulle, and we all were ready to willingly give our lives in the performance of whatever mission might be assigned us. We were men! We were comrades! We were friends! We were brothers.

That mutual respect transcended the differences in rank. Our officers and NCOs necessarily maintained a certain social distance from the enlisted men—efficient command and operations required it.

But we knew that whatever their rank, if they were in England with us, they had made the same sacrifices we had made and had the same willingness to die fighting for the cause we all believed in. We respected and believed in them, and they in us.

We were indeed a brotherhood, a family. We became 3rd Company, 501st Regiment de Chars de Combat (an M4 Sherman tank battalion), 2nd French Armored Division.

(NOTE: 3rd Company of the 2nd French Armored Division numbered 149 officers and men when it landed in Normandy as part of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.’s U.S. Third Army on August 4, 1944—two months after the initial D-Day landings, known as Operation Overlord.

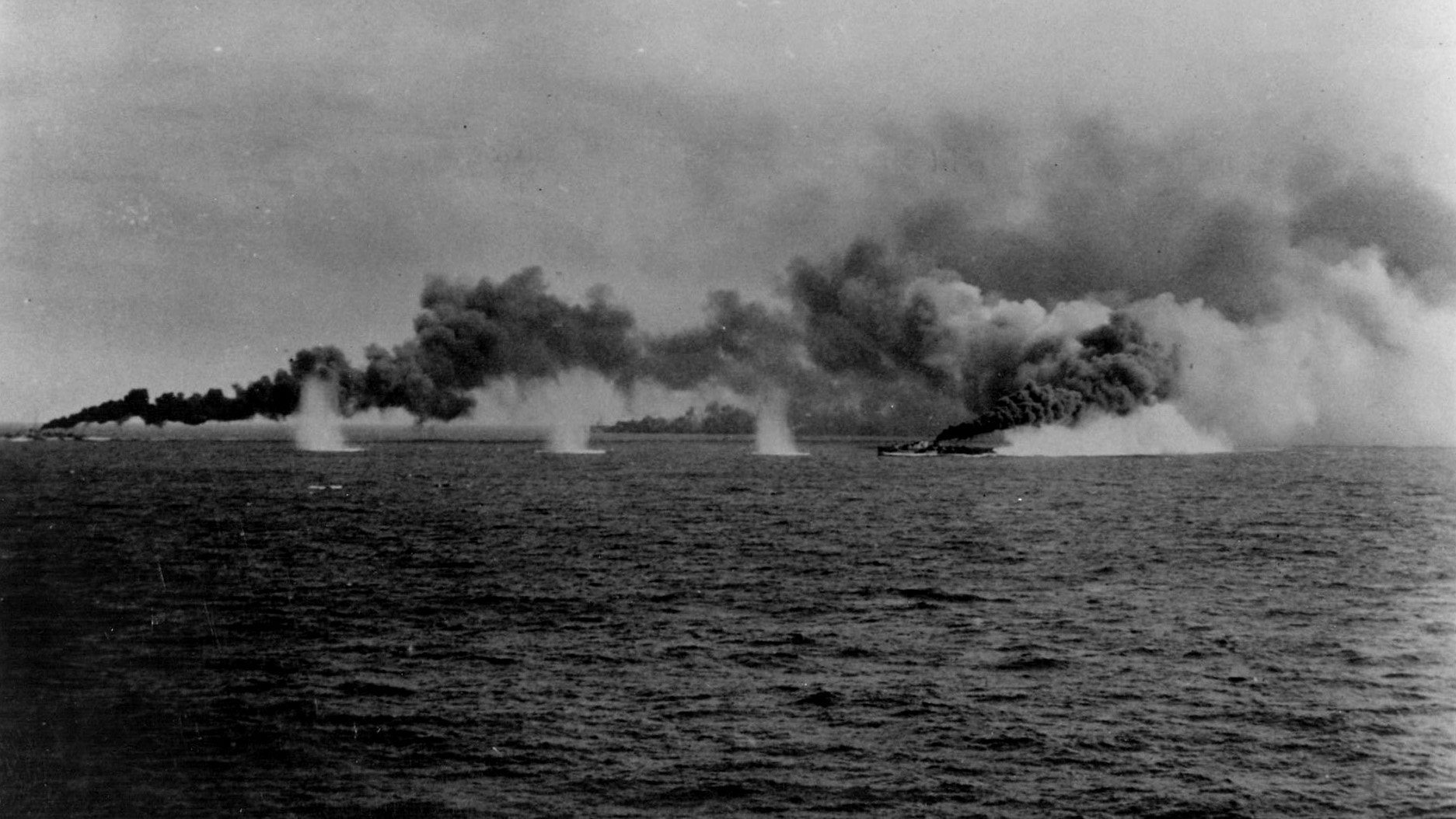

(From Southampton, Leclerc’s 2nd French Armored Division, which had over 14,000 men and hundreds of Sherman and Stuart tanks, self-propelled artillery, halftracks, jeeps, and trucks, reached French soil at Utah Beach in Normandy as part of Patton’s Third Army. There was still evidence of the fighting that had taken place there two months earlier—demolished buildings, destroyed German and American vehicles, bomb craters, and temporary cemeteries.

(The 2nd French Armored Division played a crucial role during the battle of the Argentan-Falaise Pocket and all but destroyed the Germans’ 9th Panzer Division; Champion did not write about those actions but focused his attention on his tank’s role in the liberation of Paris.)

Arriving in Paris

I shall never forget the morning of August 25, 1944, when the Free French 2nd Armored Division entered Paris. Two days earlier we were in Argentan when we received orders: Eisenhower had given permission for our division, and the U.S. 4th Infantry Division, to quickly advance on the capital city. An uprising there by the Resistance had sped up our timetable, and it was urgent we arrive before the Germans decided to destroy the city, just as they had done to Warsaw.

Our 3rd Company, commanded by Captain Branet, was not the first unit to arrive, however. An advance party of half-tracks from the 9th Company, 3rd Battalion, reached City Hall on the evening of August 24, but they became essentially surrounded. Our company arrived the next morning.

I shall never forget that triumphal entry as long as I live. Above us, the sky was clear and dazzling blue, and there was the warm and invigorating smell in the air of a perfect summer day. French flags, forbidden and concealed during the four years of occupation, were draped from every window and every doorway. Never had the sight of that tricolor thrilled me more deeply.

(Most of the tanks were given nicknames by their crews; René’s was Mort-Homme—“Dead Man.”)

The Parisians, radiant with the joy of their deliverance, surged like a restless, sun-flecked sea about our tanks as we rolled through the cobbled streets. As we passed, their cheers and applause echoed and re-echoed in the thin morning air.

Into that kaleidoscope of color, into that maelstrom of sound, we rode our lumbering metallic beasts, awed by the historicity of the event, overwhelmed by the wild acclamation of the Parisians, rapturous at the realization that we had finally reached our beloved Paris.

To our surprise, the Germans, who had resisted our advance so tenaciously the day before, were for the present nowhere to be seen. As we rode through the city streets, heads high, hearts swollen with pride, eyes shining, black berets at a jaunty angle, I almost had the feeling that the war had come to an end and that I was taking part in a victory parade.

The feeling persisted throughout the morning. While we waited near the center of the city for the Germans to respond to an ultimatum delivered to them by one of our officers, the citizens of Paris overwhelmed us in an orgy of rejoicing. They filled the streets singing, dancing, laughing, and hugging each other in happiness. They swarmed over our tanks like ants, crowding around us, showered us with gifts and kisses, and elbowed each other out of the way to shake our hands or just to touch us.

For those few hours while we waited, the war was forgotten and an enchantment as golden as the sunshine above us reigned in our hearts. Not for all the treasures in the world would I have wanted to be anywhere but in Paris at that moment!

If the day had ended right then, I would have felt that it had been the most stirring day of my life. Nevertheless, it was far from over. The liberation of Paris was being celebrated, but the city was still held by the Germans. As one o’clock approached—the hour at which the ultimatum to the Germans was due to expire—we learned that they would not surrender the city without a fight.

The emotions I was to experience in the battle for Paris, although entirely different from the ones I had just felt, were to be in every way as intense. My five-tank platoon was assigned the key mission—capture the German headquarters of Paris and its commander, General Dietrich von Choltitz.

That objective lay now barely a mile ahead along the rue de Rivoli—the Hôtel Meurice, a squat building on the corner of the rue de Castiglione. All these buildings, as well as the Jardin des Tuileries facing them, were German strongholds. Our task was to neutralize them so that our infantry could capture the Meurice.

Promptly at one o’clock, we left the now-silent crowds behind us and began to advance slowly and in single file along the deserted street. For a few moments nothing happened. Then I heard the long stutter of a German machine gun. The battle of Paris had begun.

As we moved forward, I kept my eyes glued to the periscope (I was the tank driver). I could see little, save the tanks in front of me and the smoke and explosions of German vehicles that our guns had set on fire. Above me I could hear the incessant drumming of our turret machine gun and the occasional boom of our cannon, followed immediately by the ringing sound of empty shell casings as they were ejected.

Under fire in Paris

Suddenly I heard the voice of my tank commander, Lieutenant Albert Bénard, in my earphones: “Faster, Champion, faster!” A moment later, Mort-Homme was rocked by a tremendous explosion, and it began to fill with thick billows of acrid smoke. This incident was captured by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre in their best-selling book, Is Paris Burning?:

“Lieutenant Albert Bénard, the commander of the Mort-Homme, felt [the grenade] bang his head and slide down his back to bounce into his turret. Sliced from his forehead to his waist by its shards, his tank suit in flames, Bénard scrambled out of the smoking tank. His gunner went with him. Left alone in the choking machine, Jean Réne Champion tried to drive it forward, looking for cover.”

I knew immediately that we had been hit, and I remember the surprised thought flashing through my mind that I was not dead.

Stunned by the explosion, I let the tank roll forward for a few moments before I realized that it was on fire and that all the ammunition in it could explode at any second. Quickly I brought the tank to a stop and killed the engines. I tore off my earphones and throat microphone, undid my seat belt, threw open my driver’s hatch, and started to scramble out.

As I did so, the vision suddenly came to me of the charred and mutilated bodies that I had so often seen in the destroyed tanks of other companies during our battles across France.

I was filled with terror at the thought that my comrades might be lying wounded in the turret and unable to get out without help. Fearfully, I climbed back into the tank to get a fire extinguisher.

Once outside again, I stood on the back of the tank and sprayed the inside of the smoking turret. I could only see black smoke and flames, but I was sure my fellow crewmen were inside, dead or wounded, and the thought brought tears to my eyes. I expected that the tank would explode at any moment, and the fear that I would be torn to bits by the explosion made my knees tremble.

But, somehow, that fear was not strong enough to counterbalance the concern that I had for my comrades, and I continued to wield my extinguisher until it was empty. As I prepared to climb into the turret, I heard a voice call my name.

At first, I thought it came from inside the tank; then I realized that it had come from the street. I looked down—there I saw Duten, my co-driver, crouched against the tracks of the tank. In his arms he held the smoke-begrimed and blood-soaked form of the loader, Jacques Diot.

I jumped down to join them. Duten told me that the Germans had dropped hand grenades into the open turret from the windows of the buildings along the street. I also learned from him that by some miracle the entire crew had managed to get out alive.

Diot was conscious and was moaning softly. Together Duten and I dragged him behind the arcades that line the rue de Rivoli. There the three of us crouched behind a pillar and wondered what to do next.

In the Jardin des Tuileries across the street, the Germans had seen us and were firing at us. We could hear the crack of their rifles and felt the splinters of stone against our faces as the bullets struck the wall beside us.

Mort-Homme stood abandoned in the middle of the street, a thin wisp of black smoke still rising from its turret. The sight wrenched my heart. Out of the corner of my eye I could see the sparkling August sky and, as I looked for our troops who were still hundreds of yards away, I thought none of us would ever again see an August day.

Suddenly I heard a noise behind us. Turning quickly, I saw two faces peering at us from above a transom. Sure that they were Germans, I reached for my pistol, but before I could fire, one of the faces asked, “Are you French?” It was a shopkeeper and his daughter who had been observing us for some moments, and who had thought at first that we were German soldiers.

Taking cover

When we convinced them that we were friends, they raised the steel shutter in front of the entrance to their store just high enough to let us slide under it. In the darkened shop the three of us lay on the floor for just a moment and basked in the sweet warmth of safety.

The shop sold linens. While Duten and I tore up what were probably some of the finest tablecloths in Paris to make bandages for Diot, the man and his daughter brought a bottle of cognac and some glasses.

Poor Diot had passed out; he was riddled with shrapnel from head to toe. As I wiped blood from his face, I saw that he was terribly pale, and I was sure he was going to die. I suddenly decided that Duten and I were doing him no good, and I determined that I had to try to get back to our troops and return with a medic. Against the protestations of Duten and the shopkeeper and his daughter, I slipped under the steel shutter and out into the street.

I was alone. Our infantry was still two blocks away. Pistol in hand, crouching, hugging the walls of the buildings, I began to run toward them. At the first street corner I almost bumped into a German officer. What he was doing there, God only knew, but it was a fatal circumstance. Although he, too, had a pistol in his hand, he probably never expected to find a French soldier there.

His surprised hesitation gave me time to fire first, and I brought him down with one shot. It was the first man I had ever personally killed, and as I looked at his inert body sprawled on the sunlit sidewalk, I felt a sudden darkness enter my soul.

I resumed running. Our troops were just a block away now. I could see them crouching and flattened against the walls, firing into the street ahead of them. It suddenly dawned on me that they might mistake me for a German since I was still in German-held territory. I put my Colt pistol back into its holster, raised my hands above my head, and walked slowly toward them.

“What a stupid way that would be to die,” I kept thinking to myself—shot by my own troops—and I offered a silent prayer that they would look carefully before firing. Fortunately, they recognized me and, a few moments later, I was safely in their midst.

I was unable to find a medic to bring back to Diot, but a young civilian stretcher-bearer agreed to accompany me. Everything went well until he realized that I intended to have him cross through the still-raging battle and into a sector still under enemy control.

When we reached the edge of the battle line, he refused to go on. I have to admit today that he was probably right, but then I could only think of Diot, who was probably dying. I pulled out my pistol and promised my stretcher-bearer that if he didn’t march, I would put a bullet through his head. The poor young fellow didn’t have much of a choice.

We must have made a strange and comical pair as we scurried back under the arcades of the rue de Rivoli. In one hand he held one end of the stretcher while, with the other, he waved a white handkerchief to show that he was a noncombatant. I held the other end of the stretcher in my left hand and waved my pistol at him with my right hand.

I kept repeating to him that if he didn’t move faster, he was going to die, whether he wanted to or not. Somehow, we made our way back to the linen shop unscathed. Diot had regained consciousness and seemed to be feeling much better, although he was still in pain.

When I saw that I could do nothing more for him, I went out to get my tank. It had not exploded, and the fire was now out. I climbed in, started the engines, turned it around, and set out to find the rest of my platoon.

Our mission had been successful, but it had also been costly. In my platoon alone, four of our five tanks had been hit by grenades, and two of our tank commanders had been killed. More than a dozen other men, out of a total of twenty-five, had been injured. Among them were my own tank commander and my gunner, as well as Diot.

(General von Choltitz refused Hitler’s orders to burn Paris to the ground and surrendered the city to the Allies.)

The dream realized

Much later that night, after the battle for Paris had been won, I lay next to Mort-Homme in the Jardin des Tuileries and tried to sleep. I couldn’t. My mind was reliving that incredible day. I thought about the wondrous joy of the Parisians, about Diot and my other wounded crewmen, about the linen shop, and the dead German officer.

But most of all I thought about Paris—beautiful, wonderful Paris! How we had cherished the dream that we might someday be the ones to liberate it! For four years that dream had been our constant companion—across the deserts of North Africa, on the heaths of England, and among the hedgerows of Normandy. But we had never dared to believe that it could actually come true.

Now, late in the Paris night, I realized that it was no longer a dream. The dream had become truth, and the truth was far more thrilling and deeply satisfying than I had ever imagined.

René’s Sherman tank Mort-Homme was repaired after Paris but was destroyed in a battle in the village of Badonviller in the Lorraine region in November 1944. René’s face was burned in that action, and he spent several months recovering before he rejoined his unit in late January or early February 1945. The tank is still there in the Badonviller town square, serving as a memorial to the Free French Forces who lost their lives in the liberation of their homeland.

A replacement Sherman, Mort-Homme II, was knocked out in December 1944, and the commander, René’s friend Henri Jolivet, was killed. In early 1945, Mort-Homme III, under the command of Sergeant René Champion, was commissioned and survived the war.

After the war ended, 3rd Company counted its losses: 30 killed and 78 wounded, including six who were wounded more than once.

Champion, too, survived. Following his return to the United States, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen on December 10, 1951, and in 1959 married Arlene Leslie Gordon. They had four children: Marc, David, Peter, and Michele. René also had two children—Peter and Michele—with his first wife, Hertha Schweinburg.

René Champion graduated magna cum laude from City College of New York and earned a Ph.D. in Anthropology from Columbia University. He spent 33 years working in the private sector as a defense analyst, manager, and executive stationed in Europe and the U.S. After moving from Belgium to the Denver area in 1973, he taught Anthropology part-time at the University of Denver and Metropolitan State University of Denver following his retirement from the Johns-Manville Corporation in 1990.

His life story is documented in an autobiography titled The Best Days of My Life: Memories of a Hobo Soldier. In 1994, Jean René Champion received France’s highest award—the Legion of Honor. He passed away on December 16, 2014, and is buried in Morrison, Colorado.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments