By David H. Lippman

Above all, the island was defendable. From Ritidian Point in the north to the extreme southern coastline, Guam is 34 miles long, made in an irregular shape covering 228 square miles, the largest of all Pacific islands between Japan and New Guinea. It is surrounded by coral reefs, and the island’s mountains rise more than 500 feet.

Prewar Guam had only a few miles of asphalt roads. As soon as the rainy season began in July, the dirt roads would turn to mud. July was also typhoon season, and tides would be unusually high. In July 1944 Guam was the next target for invasion. The Marianas island chain was critical to the American advance against Japan. In American hands, the islands would become major air and naval bases. Guam was also prewar American territory. Won from Spain in the 1898 war and confirmed by treaty in 1901, the island’s 22,290 residents (1940 Census), while not American citizens, lived under the protection of the American flag.

Japanese Occupiers of Guam

After Japan conquered the island on December 10, 1941, the islanders groaned under enemy rule. The Japanese confiscated land and reduced the island’s farmers to the level of slaves working in the rice fields. As the war droned on, the Guamanians were impressed to build defenses against American attack.

The Japanese planned to move the veteran 13th Infantry Division from China to the Marianas, but only sent 300 men in an advance detachment. They then assigned the 29th Infantry Division, part of the Kwantung Army in Manchuria, to the Marianas, under Lt. Gen. Takeshi Takashima. The Japanese also sent the 29th Infantry Division under Maj. Gen. Kiyoshi Shigematsu. This was divided into the 48th Independent Mixed Brigade (2,800 men) and the 10th Independent Mixed Regiment of 1,900 men.

The Marianas came under the command of the 31st Army, under Lt. Gen. Hideyoshi Obata, who was on an inspection trip on Palau when he learned the Americans were invading Saipan. He rushed back at once but could only get as far as Guam and stayed there, sharing command with Takashima.

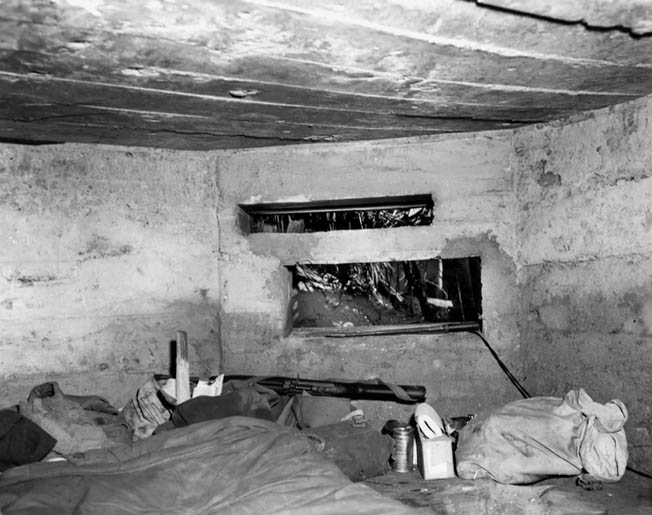

The Imperial Navy also had forces on Guam, the 54th Keibitai, consisting of 3,000 naval combat troops under Captain Yukata Sugimoto. The Japanese also had 1,800 men in two naval construction battalions that could be used as infantry and 2,000 men of the naval air force. Originally, the island held 80 bombers and 80 fighters, but all were lost. It all added up to 35,000 men, but only 19,000 of them could be seen as first-line combat troops. Static defenses included a powerful collection of weapons, including dozens of heavy guns and howitzers and 580 machine guns.

Operation Stevedore

American naval forces came under Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly and Task Force 53, and the ground forces under the 3rd Amphibious Corps, commanded by Marine Maj. Gen. Roy Geiger, a 59-year-old Guadalcanal veteran. Conolly, 52, had commanded invasion forces at Sicily and was known as “Close In” Conolly for his commitment to tight naval support of invasions.

The spear point of the corps was Maj. Gen. Allen Turnage’s 3rd Marine Division, which had fought on Bougainville. It had three regiments, the 3rd, 9th, and 21st Marines, and added up to 17,465 Leathernecks. The other corps asset was Brig. Gen. Lemuel Shepherd’s 1st Marine Provisional Brigade, which consisted of the 4th and 22nd Marine Regiments. The 22nd had suffered an outbreak of filariasis while training in Samoa which led to 1,800 transfers.

There was no designated backup for the two Marine units, but the Army considered its 27th Infantry Division, assigned to invade Tinian, and the 77th “Metropolitan” Infantry Division, originally drawn from New York City, to be the potential reserves. Ultimately, the 77th, under Maj. Gen. Andrew Bruce, was tapped for Guam.

The tactical plan for invading Guam was called Operation Stevedore and was drafted in April 1944. It set the invasion date for June 18, but the assault was postponed for a month due to the harsh fighting on Saipan.

Although Guam had been an American possession for 40 years, the United States had very little information about the island. Geiger asked for submarine patrols to contact Guamanians for up-to-date intelligence about Japanese deployments. His request was denied. The Americans would not have good maps of Guam until the invasion had begun, or even thereafter.

The Americans chose simplicity and daring for their invasion plans: the best place to land on Guam was Tumon Bay north of Agana. Both the Americans and Japanese knew this, and the Japanese defended the bay heavily. Geiger chose to contend with wide coral reefs and shallow water rather than Japanese gunfire. The 3rd Marine Division would attack at Agana, while the 1st Marine Brigade would storm ashore on the Agat beaches, surrounding the Apra Harbor and sealing off the Orote Peninsula.

Hitting the Beaches

As the Marines rehearsed the invasion, the Navy began softening up the defenders on Guam and pulverized the Imperial Japanese Navy in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The Navy began shelling Guam on June 16.

Checking the weather, Conolly decided that W-day would be July 21, and H-hour would be 8:30 am. The invasion force left Eniwetok atoll bound for Guam on July 15 and arrived right on time. Weather conditions on W-day were perfect: clear with a slight overcast and a light wind. Early on the 21st, the Leathernecks loaded into their landing craft. Navy warships opened a massive bombardment at 5:30 am, joined by air support. At 6 am, the assault units were in position. The Navy began shelling the shore at 8:03 am.

The main Marine attack was directed at 2,000 yards of landing beach between Asan Point and Adelup Point, the 3rd Marine Regiment storming ashore at Red Beach 1, the 21st at Green Beach in the center, and the 9th Marines on Blue Beach. South of Orote Peninsula, the 4th Marines were to hit Beaches Yellow 1 and 2 and the 22nd Marines White Beaches 1 and 2. The Americans expected little resistance to the initial landings at Asan. When the bombardment lifted, they returned to their positions and opened fire on the 1st Provisional Brigade.

Even so, the Asan landings were successful. Within 40 minutes, the Leathernecks were moving. The 3rd Marine Regiment lost 231 killed and wounded. Once the Marines moved inland, the fighting grew tougher. The 3rd Marine Tank Battalion’s Shermans waddled up to support the riflemen, and flamethrowers joined the attack. Soon Chonito Cliff was taken.

The 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines also ran into trouble with machine-gun fire. Captain Geary Bundschu, commanding the battalion’s A Company, tried to flank the position but was unsuccessful. He sought permission to disengage but was refused. Instead, regiment ordered a second direct attack. Bundschu fell in the assault, and his company was pinned down all day. With all weapons firing, the Marines finally silenced the machine guns with hand grenades. The 2/3 Marines were slowed by determined defense, too. The Marines promptly named the hill “Bundschu Ridge.”

Taking Agat

At Agat beach, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade faced a wide coral reef and intense enemy fire. The Japanese were protected from the low trajectory naval guns by hills and caves. Japanese troops of the 38th Regiment poured rifle and machine-gun fire on White and Yellow Beaches. Invading landing vehicles were hung up on the coral reef and drew Japanese fire.

Despite the heavy fire, the 22nd Marines stormed ashore according to plan with DUKWs bringing in Sherman tanks. These blasted open strongpoints and rumbled toward Agat village against sporadic resistance.

The 4th Marines also landed on schedule and came under concentrated fire. The 2/4 Marines were halted by Japanese fire from a hill that was not on their maps and were pinned down until noon. The 1/4 Marines found safety in a drainage ditch before regrouping and defeating the Japanese.

General Shepherd himself came ashore at noon, finding the situation critical. Despite successes, his men were exhausted, thirsty, and short of ammunition and water. Communications were a mess. A Japanese counterattack might cause chaos. At 12:45 pm, the 1/22 Marines moved through the rubble of Agat with tank support and took the town.

Suenaga’s Last Charge

The Marines headed east to seize a hill, but the Japanese machine gunners were too determined to dislodge. The 4th Marines did not do much better, even with air support. With sunset coming, Shepherd knew the Japanese would launch ferocious night counterattacks and ordered his men to dig in.

Shepherd was right. Takashima was indeed planning night counterattacks, but his forces had suffered heavy casualties and his plans lacked cohesion. Colonel Tsumetaro Suenaga wanted to hurl two battalions at the 1st Marine Provisional Brigade at 5:30 pm. At first, Takashima demurred. Then he agreed. Before launching the attack, Suenaga ordered his regimental colors burned—a sign that his command would be destroyed. The attack went in at 11:30 pm with a heavy mortar barrage on the right flank of the 4th Marines. Half an hour later, Japanese troops accompanied by four clanking T-97 tanks hit the 3/4 Marines. The Americans replied with bazookas and 75mm shells from their Sherman tanks, setting the rivet-hulled T-97s ablaze and breaking up the attack.

The Japanese tried again at 3:30 am, with Suenaga himself leading the charge. Hit by a mortar fragment, he kept charging until killed by a rifle bullet. Navy and Marine starshells illuminated the scene. The Marines wondered if their enemies were drunk. They later found caves full of liquor.

In the 3rd Marine Division’s area, there were fewer attacks, but one hit the 3/3 Marines around midnight, where Pfc. Luther Skaggs, Jr., of Kentucky, was defending a position. A Japanese grenade exploded in his foxhole. Instead of calling for a medic, Skaggs applied a tourniquet and for the next eight hours defended his position. Skaggs received the Medal of Honor from President Harry S. Truman on June 15, 1945.

Taking Bundschu Ridge

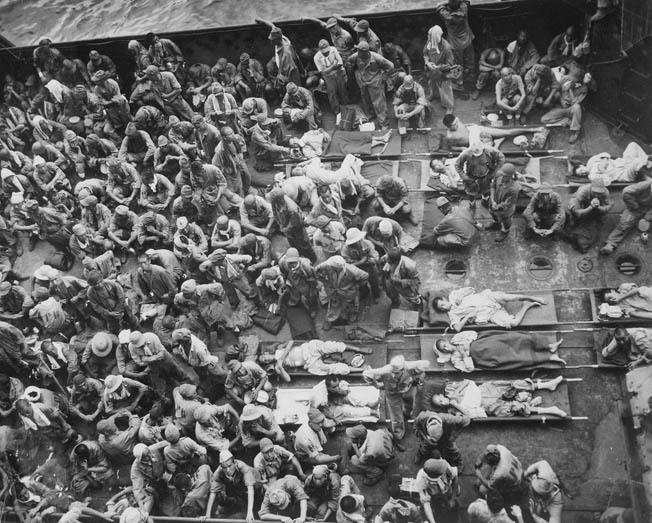

Meanwhile, the 77th Infantry Division’s 305th Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Vincent Tanzola, was to start coming ashore, and chaos soon reigned. Shepherd did not want the 2/305, under Lt. Col. Robert Adair, coming ashore, so its landing craft circled around in the tropic heat, men growing exhausted and seasick. They finally landed at 2 pm on White Beach 1, under direct fire, overloaded with 50 pounds of equipment.

The 1/305 had a harder time. Under Lt. Col. James Landrum, it was held in its landing craft until 5:30 pm. Finally, the 3/305 came ashore in the middle of the night. The 3/305 had to cope with faulty compasses, boats going off course, crossing over the reef, and missing their beach guides. Some of the men did not get ashore until 6 am.

As dawn broke on July 22, the 1st Marine Provisional Brigade counted the Japanese bodies near their front line. More than 390 were reported near one unit, 200 at another, and 69 at a third. Clearly, the Japanese had taken a major defeat.

At Asan, Shigematsu reasoned that he needed to keep the 3rd Marine Division pinned down with mortars and artillery. His gunners scored a direct hit on the 3rd Division Message Center. Japanese infiltrators tried to break open the seam between the 3rd and 21st Marine Regiments but were defeated.

With the attack defeated, 1/3 Marines were ordered to attack Bundschu Ridge and again failed to take it in the first assault. The Marines changed their tactics, moving two companies to flank the Japanese on the ridge, while two other companies attacked directly ahead. At 10 am, the attack went in with Company C of the 1/3 heading around to the right. Japanese fire stopped them cold. Companies A and E moved straight ahead against the ridge backed by tanks, half-tracks, and mortars. This attack succeeded. The Marines reached the top of the ridge. Kentucky Marine Pfc. Leonard Mason received the Medal of Honor for his heroism during the action.

Even though the Marines took the ridge, they were too few to hold the ground—the 3rd Marines suffered 615 casualties on July 22. Company A of 1/3 Marines was no longer effective. The 21st Marines had an easier time, sending out patrols, and 9th Marines took the old Piti Island Navy Yard against light resistance.

Restoring Order to the Invasion Force

Meanwhile, 3/9 was loaded into LVTs and assigned to seize the small Cabras Island off shore in the early afternoon, under heavy naval fire. Cabras turned out to be lightly defended. Meanwhile, in 1st Marine Provisional Brigade’s sector Shepherd struggled to restore order to his jumbled command. The 305th was in bad shape from its sloppy unloading. It took all morning to get it into position to relieve the 2/4 Marines. The 22nd Marines attacked from positions north of Agat toward Old Agat Road, seeking to isolate Orote Peninsula. The 4th Marines advanced on Mount Alifan. The 1/4 reached the summit but found it too dangerous to stay there if the Japanese counterattacked and withdrew to a more defensible position.

That evening, Takashima dithered again, reluctant to make a major counterattack. He was determined to hold the Orote Airfield and the old U.S. prewar Marine barracks. At the same time, Geiger decided to land the 306th Infantry on White Beach starting at noon on the 23rd.

When the 306th went in, the Army men found trouble again—their DUKWs and LVTs could not cross the coral reefs. Vehicles had to be pulled ashore by bulldozers. Army General Bruce complained about how his men were being treated, requesting that his last regiment come ashore and the division be put under his command as a unified force, not as an attachment to Shepherd’s brigade. Geiger was reluctant to land his floating reserve but decided to do so on the 24th.

The 307th’s experience coming ashore was similar to the other two regiments, with the added agony of a storm at sea that created swells. While the GIs suffered seasickness, the Marines advanced through rice paddies, swamps, and hills. Numerous 14-inch shells from the Pennsylvania shredded Japanese positions around Mt. Tenjo.

50 Percent Strength

Shepherd now prepared to isolate the Japanese forces on the Orote Peninsula with the 22nd Marines. Naval barrages, air strikes, and tank support buttressed the attack on July 24. The covering fire blasted the barricades and sealed up Japanese caves. The Japanese sent in five tanks, and the American Shermans made swift work of them. But in four days of fighting, the 1st Brigade had suffered 1,003 casualties and 188 killed in action.

On July 23, the 3rd Marines attacked the Japanese right flank supported by aircraft and division and corps artillery. The 2/3 Marines tried to flank Bundschu Ridge and found the Japanese had abandoned most of it. The Japanese counterattacked against 3/3, and its commander warned his bosses that his manpower situation was critical—A Company was down to 40 men.

On July 24, the Marines attacked again with the 21st and 3rd seeking to reach Fonte Plateau and tie together their exposed flanks. To the south, 9th Marines tried to link up with 1st Brigade. It failed; however, the Japanese seemed to be abandoning defensive positions.

By July 25, the Americans were beginning to address their supply and organization problems, landing defense battalions, combat engineer Seabees, and water tanks. That day, the 2/9 took up the attack on Fonte Plateau at 9:30 am with effectiveness despite an incident of friendly fire that resulted in 15 Marine casualties. The 2/21 and 3/21 Marines also advanced behind pulverizing air and artillery support, finding 250 dead Japanese lying in their ravine.

The 9th Marines did better, taking high ground north of the Aguada River and capturing several supply dumps intact. In the dumps they found great quantities of soft drinks and Asahi beer. However, the 3rd Marine Division was holding a line 9,000 yards long, a severe stretch for the depleted force. Some of Shepherd’s units were down to 50 percent strength.

“Defend Guam to the Death”

July 25 was intended to be a day of reorganization and rest for the invaders, but fighting continued anyway as Shepherd worked to seal off the neck of the Orote Peninsula, facing Japanese pillboxes, fortifications, and more tanks. The defenders were mostly naval troops of the 54th Keibitai, under Commander Asaichi Tamai. Japanese Type 97 tanks, armed with 47mm guns, could not cope with the American M-4 Shermans, and the Japanese lost eight tanks. Some 2,500 Japanese troops were now trapped on the peninsula.

Tamai realized he had only one choice now: a night banzai charge by all of his men—to link up with Takashima. He passed out every weapon his ammunition officers could find. Then he issued all the beer, saké, and synthetic Scotch on the peninsula to build up the men’s courage for the grand assault.

Luckily for Tamai and his porous plans, Takashima was planning the same thing—a massive night assault by his 10,000 men, coordinated with Tamai’s attack. It did not seem like a good idea, but on the 24th Tokyo radioed Takashima: “Defend Guam to the death. We believe good news will be forthcoming.”

With that in hand, Takashima assembled the 18th Regiment and the 48th Brigade. They would strike from the Fonte Plateau against 2/9, under Lt. Col. Robert Cushman, and drive all the way to Red Beach 2. Meanwhile, two battalions of the 18th Regiment would hit the 21st Marines and another battalion the left wing of the 9th Marines. They would use the shallow Asan and Nidual River valleys to take advantage of the 800-yard gap between the two Marine regiments.

The Marines’ Own “Marianas Turkey Shoot”

Heavy rain began pouring from the Guam sky on the afternoon of the 25th. GIs and Leathernecks huddled in flooded foxholes. The Japanese assembled unseen against the 3rd Marine Division. However, the attack on the 1st Provisional Brigade went badly, with most of the naval attackers apparently drunk. They charged forward in white uniforms, which made them highly visible in the dark.

Soon starshells illuminated the scene for the Marine artillery. Many of the Japanese troops fled into swamps. Incredibly, they regrouped and hurled a second assault at the 1st Brigade. The Marines called it their own version of the “Marianas Turkey Shoot.” One Marine platoon found 256 Japanese dead in front of its positions without losing a single Leatherneck.

As the attacks failed, the Marines were content to save their own casualties by letting the survivors flee behind a curtain of shells. Dawn found 400 Japanese sailors dead on the field and 600 more dying or wounded for a loss of only 75 Marines.

In the northern attack, the Japanese jumped off at midnight. The Marines relied on discipline, training, and marksmanship to fend off the assaults. The 1/21 had only 250 men to hold a front of 2,000 yards, which would normally be held by 600 men. Turnage ordered his engineers, headquarters, service, and motor pool men to be ready to go to the front.

At 3 am on July 26, signal flares told Major Chusa Maruyama to lead his 2/18 Regiment against the American 1/21 Marines at one of their weakest points. In the light of the signal flares, the American machine guns mowed down the attackers. The 21st Marine line turned into clumps of men trying to hold positions and stay alive under the waves of Japanese attacks.

A Second Failed Attack

The second portion of Takashima’s assault was 3/18 Regiment, led by Major Setsuo Yokioka. They captured two machine-gun positions but were stopped by a Marine counterattack. The Japanese found the half-mile gap between the 21st and 9th Marines and poured through it, seizing the high ground. Colonel Wendell Duplantis, leading the defenders, prepared to destroy his cipher device and mobilized three platoons of his weapons company, backed by cooks, bakers, clerks, and other rear-area Marines, to face the Japanese.

Some of Yukioka’s men made it into the 3rd Division’s headquarters area, which surprised everyone there, but the headquarters and 3rd Motor Transport Battalion men reached for their rifles. They fended off the attack, but some of the Japanese broke into the division’s hospital area at 6:30 am. Most of the severely wounded had been evacuated to the beach, but there were still doctors, corpsmen, and less seriously wounded, and the latter held off the Japanese.

The Japanese advantages of attacking from high ground by night into seams in American lines disintegrated as Takashima’s armor got lost in the darkness and could not engage the Americans. Worse, while the Japanese troops had their morale raised by the heavy issuance of beer, saké, and wine, the liquor also unraveled discipline. By dawn, 90 percent of the Japanese officers involved in the attack lay dead or mortally wounded.

4,ooo Dead in Takashima’s Counterattack

Facing certain defeat, not knowing what to do, the leaderless Japanese survivors reacted in typical fashion. They took off their helmets, placed primed grenades on the tops of their heads, replaced the helmets, and waited for the inevitable. On the extreme left of the American beachhead, the 48th Brigade made seven separate attacks against the 3rd Marines and 2/9 Marines, who were low on ammunition.

Nearby, Captain Louis Wilson, commanding Company F, 9th Marines, led his troops against the Japanese. He received the Medal of Honor for gallantry under fire. Incredibly, Wilson not only survived this battle, he stayed in the Marines and became the 26th Commandant of the Corps, serving in that role from 1975 to 1979.

The 48th Brigade took a beating in its failed counterattacks, suffering more than 950 dead. The Japanese tactics and operations were sloppy. They captured most of the mortars and ammunition of the 21st Marines, for example, but did not turn them against the Americans. When the Marines counterattacked to recapture their property, the Japanese did not destroy the mortars. Daybreak found weary Marines in possession of the battlefield, evacuating their wounded, and inspecting the more than 3,500 dead Japanese lying in heaps. Marine casualties were 166 killed and 645 wounded.

Geiger chose to proceed cautiously. He went ashore at about 1 pm and ordered his men to bring up more ammunition, tighten the perimeter, and string barbed wire against further attack.

On the other side, Takashima and his staff reviewed the results of their futile attack. As many as 95 percent of the attacking officers lay dead. Worse, 90 percent of the weapons were destroyed. Nearly 4,000 of his men were dead. The only purpose to the struggle now would be to inflict damage on the Americans as they moved inland. Takashima’s counterattack was the decisive battle of the Guam campaign.

Capturing the Orote Peninsula

Geiger had to continue his attack while assuming the enemy still had formidable resources. Studying his casualty reports and maps, Geiger decided not to commit the 77th Division until the Orote Peninsula had been captured, the Fonte Plateau taken, and the front line secured.

The first task was destroying the Japanese defenses on the Orote Peninsula. This was a job for Shepherd and the 22nd Marines on the right and the 4th Marines on the left. The attack was to go in at 7 am on July 26, with the Army’s 902nd Artillery firing the first of more than 1,000 rounds in deep support. The Americans brought up Marine and naval artillery. Channeled up the Agat-Sumay road, the 22nd’s advance came under Japanese mortar and artillery fire. Meanwhile, the 4th Marines, advancing on the right, met light resistance.

The Japanese pounded the Marines with mortar and machine-gun fire, forcing the Americans to bring up tanks, which pushed through the Japanese defenses only to uncover another line of pillboxes and dugouts just east of the old Marine barracks area.

The 4th Marines had an easier day but faced a number of Japanese banzai attacks. Curiously, after dark Japanese defenders, instead of forming up for a suicide attack, broke and ran, an unusual spectacle.

On the 29th, the offensive resumed, and the 22nd found the enemy in front of them collapsing. The Leathernecks took the old Marine barracks ground by noon and moved on the outskirts of Sumay.

By contrast, the 4th Marines had a tougher day. They fought through thick undergrowth and against strong defensive lines. The 4th Marines’ commander, Lt. Col. Alan Shapley, asked Shepherd, who was visiting the front, for tank support. Shepherd sent up two platoons of Marine Sherman tanks and asked Bruce for a like number of Army Shermans. Bruce had only landed his M5 Stuart light tanks, but he obligingly sent them up. The tank-infantry teams went straight to work, grinding Japanese positions.

At dawn on the 29th, Shepherd unleashed a massive artillery and naval bombardment. When the Leathernecks attacked at 8 am, they were supported by every tank Shepherd could find, including M-10 tank destroyers. By noon, the airfield was captured.

Assault on the Japanese Line

With the Orote Peninsula and victory in hand, 1/22 and 2/22 were ordered into reserve, while 3/22 cleaned up the last resistance. On the afternoon of the 29th, the 2/22 made the victory formal. With Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance, “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, Geiger, and Shepherd present, an honor guard from 2/22 raised Old Glory over the battered remains of the prewar Marine barracks. Total U.S. casualties for Orote Peninsula were 116 killed, 721 wounded, and 38 missing. Some 2,500 Japanese soldiers died.

The 3rd Marine Division was short on men and ammunition, thinly stretched, and all hands needed a rest. Geiger believed that the Japanese night attack of the 26th was the last offensive shot in the Nipponese locker, and he was determined to regain the initiative, ordering his force into a major assault against the Japanese line.

On the morning of the 27th, the 3rd Marine Division attacked on a broad front from Fonte in the north to Mt. Tenjo in the south. The 21st took the lead in the center, driving on the high ground with its radio towers and main north-south power line. The 2/21 was held up by swampy ground and Japanese machine-gun fire and required tanks moving around the swamps to blast open the defenses. By late afternoon, 2/21 was just short of the power lines.

The 1/21 had a tougher day, halted by Japanese troops dug in along the slopes of a small hill. The Americans brought in guns, planes, and tanks, but the Japanese would not retreat. The 3/21 on the right flank faced less resistance but was delayed by trying to keep connected to the Leathernecks on its left.

At the Fonte Plateau, 2/3 faced moderate resistance as it bypassed enemy strongpoints. The 2/9 had a hard day, too, being hit by friendly fire. It spent an hour reorganizing but by mid-afternoon had reached its portion of the power lines.

11 Counterattacks on Fonte Plateau

Studying his maps, Geiger ordered the Fonte Plateau captured on the 28th, and all other Marines to advance in their sectors. Reinforced by the Army’s 3/307, the 9th Marines attacked the Mt. Chachao-Mt. Alutom line against the usual determined defense.

On the left flank, 2/3 and 2/9 advanced on the Fonte Plateau, moving into a large depression that the Marines named “the pit.” Even small Leatherneck patrols working into the pit came under fire from many directions, halting their advance. With Turnage’s permission, Colonel Cushman delayed the attack until he could bring up heavy demolition charges, flamethrowers, and rocket launchers to the pit

At dawn on the 29th, Cushman opened up with crisscrossing fire into the pit. After the bombardment, Marine assault teams moved in, ordered to kill any Japanese left. The Marines cleared the pit without a single casualty.

The 21st and 9th Marines also resumed their advance and found only sporadic enemy fire before achieving their objectives. The 2/9 had lost 75 percent casualties in two of its rifle companies and 50 percent in its third.

Takashima saw the importance of holding Fonte Plateau and had resisted with determination, hurling in 11 separate counterattacks, all of which had been failures and cost him at least 800 irreplaceable men.

Killing Takashima

Meanwhile, the bulk of the Army’s 77th Division awaited its opportunity to contribute to the battle. The men had recovered from their seasickness and were ready to go but literally stuck in the muddy terrain. Geiger drew up his plan for the final liberation of Guam. The major task was to drive north. The 77th would be on the right, the 3rd Marine Division on the left, with 1st Marine Brigade mopping up the remaining Japanese holdouts on the southern half of the island. The 3rd Marine Division began struggling toward Fonte Plateau, while the Army’s 305th Infantry Regiment began heading toward Mt. Tenjo.

Company A of 3/305 reached the top of Mt. Tenjo at 8:30 am on July 28. The 2/307 took over and consolidated, hooking up with the 3rd Marine Division on the left, and Phase One of the Guam operation was complete. American casualties were 5,733, with 513 killed in action, most of them Marines. The Provisional Brigade reported 75 percent efficiency, 3rd Marine Division 80 percent efficiency, and 77th Division in excellent shape. Japanese dead were estimated at 4,192.

On the 28th, Takashima personally took over the defense of the Fonte Plateau. When the position was lost, Takashima ordered his men to withdraw and reassemble north of the Agana River. Marine machine gunners caught the general and his party and opened fire. Takashima died immediately.

Salmon and Candy For the 307th

Command of Guam’s defenses went up the chain to Obata. As senior Japanese officer on the island, he now had to command the troops as well as the entire 31st Army tasked with holding the Marianas. He promptly set up his headquarters in the central Guam town of Ordot. He concentrated 1,000 surviving combat troops, 800 naval infantry, 2,500 support troops, 12 tanks, and some guns into a motley force.

Obata ordered a withdrawal to Mt. Santa Rosa to establish two blocking positions, one near Finegayan, the other near Barrigada village. The Japanese defense would be a series of small unit delaying actions. However, the Americans did not know the depth of the Japanese troubles. Geiger decided to proceed cautiously.

After two days of deploying troops, passing out ammunition, and typing up memos, the Americans were ready. The 3rd Marine Division had to shift slightly to get in position for attack, while the 77th would have to drive across the waist of the island and realign its regiments into position. The Marine objectives were Tiyan airfield and Finegayan, while the Army aimed for Barrigada and Mt. Santa Rosa.

On the night of July 30-31, Army, Marine, and Navy artillery blasted Japanese positions. The Marines launched their attack at 6:30 am and faced sporadic fire and enemy mines. Within four hours, the Leathernecks entered Agana. By noon the entire town was under Marine control. The Leathernecks found Guam’s capital badly damaged and filled with mines and booby traps.

Against slim opposition, the Marines moved fast. The 21st faced one brief firefight with an enemy pillbox, reaching its objective line by 2 pm. The 9th’s forward movement was held up by difficult terrain and a few Japanese defending a supply dump near Ordot. They counterattacked with two tanks, and Marine bazookas disposed of them.

The 77th drove across Guam’s waist and found no resistance until late afternoon. Bruce used his troops’ fatigue in his favor. He told the 307th’s Colonel Hamilton: “Capture that [the cross-island] road, and we’ll bring up your breakfast.” The 307th did so, and Bruce sent forward captured Japanese salmon and candy.

Battle of the Reservoir

By nightfall on July 31, the 77th had almost reached Pago Bay. The next day, August 1, the Army reached the east coast. By noon, the 307th had reached and secured the Agana-Pago Bay road. By the evening of August 2, Geiger had both of his divisions in position for the final assault. The 77th also won the respect of the Leathernecks, who now called it the “77MarDiv,” a high accolade. Lt. Gen. Holland M. Smith wrote that the 77th showed a “combat efficiency to a degree one would only expect from veteran troops.”

With a third of the island remaining to be liberated, the outcome was clear. Geiger intended to fight his battle in a manner designed to keep American casualties low. His next objective was the town of Barrigada, which had a huge reservoir capable of pumping 20,000 gallons of water a day. The “Battle of the Reservoir” would be the 77th Division’s next major fight.

Progress remained slow. Bruce hurled his two regiments forward on August 2 and ran into trouble. The 3/307 was halted by machine-gun fire. One battle swirled around a newly built Buddhist temple and a two-story greenhouse. Bruce ordered a coordinated artillery, tank, and infantry assault at 1:30 pm, and it failed. By day’s end, the 77th had fallen short of its objectives and suffered 125 casualties.

Things improved the following day. On August 3, a walking barrage preceded the 307th’s riflemen, who took the Barrigada Well three hours after going forward. The 3/307 reached the top of Mount Barrigada by midafternoon. The next day, the slow, methodical advance continued. However, tragedy occurred when a signals snafu resulted in Marines of 2/9 and tanks supporting the 307th swapping fire. On August 8, the Marines caused chaos when their own artillery fired on 2/306.

Col. Douglas McNair: The Highest-Ranking Casualty in Guam

It was clear now, though, that the Japanese were conceding most of the good defensive positions and were falling back on Mt. Santa Rosa in the island’s northeast corner for a last stand.

August 5 saw the Army struggling through some of Guam’s worst jungles amid pouring rain, up and down slippery trails. Tanks and tank destroyers led the way, probing for sniper fire. By evening, the 305th had advanced 2,000 yards.

That evening, 1/305 tried to dig foxholes amid the coral with little success. Logically, two Japanese medium tanks and a platoon of infantrymen charged the battalion’s A Company. The Americans gunned down the infantry, but their machine guns were less effective against the rivet-hulled tanks. The bazooka men had no luck either, and the tanks rumbled through the perimeter into the company area. After a few minutes of shellfire and flares, the tanks retired unscathed, leaving behind 46 wounded men—33 of whom had to be evacuated—and 15 dead.

The two tanks turned up the next day, when E Company of the 2/305 met up with them on the only trail in the area. The tanks were in defilade when the Americans advanced, and they fired into the trees along the trail. Shermans were unable to close with the enemy in the jungle terrain. The Americans brought up heavy machine guns and 81mm mortars, forcing the Japanese crews to abandon their tanks, leaving behind three killed in exchange for 16 dead and 32 wounded Americans.

On August 6, the 77th Division’s chief of staff, Colonel Douglas McNair, set up a new divisional command post about 600 yards south of the village of Ipapao. McNair noticed a small hut approximately 200 yards off the trail and set out to investigate. A sniper hiding in the building fired a single round, killing McNair instantly. McNair was the highest ranking American officer killed in the battle. McNair’s father, Lt. Gen. Leslie McNair, head of Army ground forces, had been killed two weeks earlier by friendly fire in Normandy, the highest ranking American officer to be killed in the European Theater.

Bruce ordered 3/305 to sweep the area thoroughly. The Americans found 150 Japanese only a third of a mile from the planned divisional command post. Bruce wasted no time sending in a platoon of Sherman tanks to support his two assault companies. After a six-hour firefight, the area was secured.

Slow-Moving Through the Yigo-Mount Santa Rose Area

By now the 77th Division was closing in on the last Japanese redoubt in the sector, the Yigo-Mount Santa Rosa defenses. Yigo was a small village located at a junction of narrow roads amid the usual thick undergrowth, but Mount Santa Rosa was a misnomer—it only stood 800 feet high. The Navy steamed in with battleships, cruisers, and destroyers on August 3 and treated the mountain to point-blank fire for days.

The main effort was to be by the 77th in the Yigo-Mount Santa Rosa area. Bruce’s plan called for a turning movement, with the division shifting the axis of its advance 90 degrees. The 306th would move along the division’s left boundary supported by an attached company of tanks from the 706th Tank Battalion. After passing Mount Santa Rosa, it would turn eastward and seize the area north of the mountain. The 307th would take Yigo and then block the westward slopes of Mount Santa Rosa, backed by the rest of the 706th Tank Battalion. The 305th would be on the right and support the 307th to block off the southern slopes.

All three regiments jumped off at 7 am on August 7. The attack on Yigo went in at noon, backed by the usual heavy Navy and Army artillery barrage. Bruce’s plan called for the barrage to lift precisely at noon, so that the tanks would be in position to lead the attack. The tanks were 20 minutes late getting to the head of the infantry column. They swept ahead and disposed of Japanese machine-gun positions—and ran into an ambush. As the M5s climbed a slight rise, Japanese fire ripped open two of the tanks. The Shermans behind them came into action, but one threw a track and another stalled. The Americans were pinned down by rifle and machine-gun fire.

The tanks bypassed the roadblocks to enter Yigo, but the infantry was still pinned down. Lt. Col. Gordon Kimbrough, commanding 3/306, took quick action, detaching a platoon to move through the jungle terrain to take the defenders in the rear. His move worked perfectly. The Americans wiped out the strongpoint, and the offensive resumed.

Even so, the offensive was moving slowly. Yigo was taken by nightfall, and the 307th moved 1,000 yards past the village. The 306th achieved its ground through tank-infantry cooperation. The lead company of infantry was assigned a platoon of tanks. These took positions on either side of the road with one tank guarding the rear. Doing so, they overcame Japanese machine gunners. On the right, the 305th used bulldozers to blaze a trail.

The Last Japanese Tank and Infantry Attack

In the early evening, the Japanese tried their usual trick of infiltration attacks against the Americans but were beaten off. The last Japanese tank-infantry attack of the campaign was launched against the 3/306 along the road north of Yigo. Three tanks and Japanese infantry attacked the Americans. The infantry pinned down the American bazooka teams, while the tanks fired shells into the surrounding trees. The GIs fired a light machine gun into the 6×10-inch forward opening of one tank, killing the crew. A rifle grenade ripped open the thin armor of the second tank. The third towed away one of the damaged tanks. The Japanese killed six Americans and wounded 16, while losing at least 18 dead.

On the morning of August 8, the 306th headed up the trail to Lulog village against weakening Japanese resistance. The 306th killed more than 100 Japanese as they moved to within a few hundred yards of the ocean. The 307th slogged its way up to the summit of Mt. Santa Rosa, killing 35 Japanese. Incredibly, they found no enemy, and by 2 pm Lt. Col. Thomas Manuel, who commanded the regiment, was standing astride its summit.

By dusk, Bruce could look at his maps and see that his division had achieved all of its objectives in the northern sector of Guam, at a tolerable cost of 30 killed and 104 wounded, while counting 528 Japanese bodies. The only problem was that some 2,000 Japanese men expected to be at Mt. Santa Rosa were not there. That was a problem for the 3rd Marine Division, also conducting a slow and methodical advance.

Frank Witek’s Medal of Honor

The Marine drive began at 6:30 am on August 2 with two regiments abreast, 3rd Marines on the left and 9th on the right, connected to the 77th Division. The Marines had a hard time advancing in the dense undergrowth, gaining only one mile by evening.

While the 3rd Division advanced, the 1st Provisional Brigade was getting a bit of a break. Patrols to the south were not finding many Japanese defenders, the largest being a group of about 12 holed up in a cave near Mt. Lamlam.

On August 3, Geiger brought the 1st Provisional Brigade up to an area behind 3rd Division’s lines so that it could advance on the extreme left of the line in the final drive into northern Guam. That same day, the 3rd Marine Division attack continued. The 3rd Marine Regiment moved out at 7 am against slight opposition and covered 3,000 yards before nightfall. The 9th Marines had a harder time, hitting a company-sized Japanese unit dug in on either side of the Finegayan-Santa Rosa road just below Junction 177.

Backed by tanks and heavy weapons, Marines of B Company overcame the position by 10 am. They counted 105 enemy dead.

Some 500 yards ahead at Junction 177, the 9th Marines found more formidable defenses. Japanese troops sited their machine guns in ravines and ditches, almost invisible in the dense undergrowth. The heroism of 23-year-old Marine Pfc. Frank Witek helped crack the Japanese defenses. Witek received a posthumous Medal of Honor. On Sunday, May 20, 1945, General Alexander Vandegrift, the commandant of the Marine Corps, presented Witek’s mother with the medal at a ceremony at Chicago’s Soldier Field, before 50,000 people.

Fighting in the Finegayan Area

At 8 am, Turnage sent his division’s reconnaissance company to patrol northward to Ritidian Point. Later in the day, Company I of 3/21 and Company A of the Marines’ 3rd Tank Battalion joined the reconnaissance team. Lt. Col. Hartnoll Withers of the tank battalion was in charge of this ad hoc group. Things went wrong right away. First, the task force lacked fuel to return home. Next, the lead vehicle missed the key turn to the left and continued eastward through enemy lines and smack into Japanese fire. The defending Imperial Marines, backed by 75mm and 105mm field pieces, machine guns, and tanks. The Leathernecks took cover while their tanks ripped open the Japanese positions. That evening, the Japanese kept the heat on the Marines with mortar fire, flares, and patrols in the 9th Marines area.

On August 4, the Marines reorganized their men, putting the 21st Marine Regiment in the center and gaining ground against slim resistance. The next day the 3rd Marines moved forward, facing more trouble from undergrowth than the enemy, gaining 1,000 yards. The 21st Marines also advanced easily, but the 9th Marines and their two supporting tank platoons faced Japanese defenses backed by 75mm guns. The Marines brought up a tank destroyer to eliminate the Japanese and by evening were nearly in the village of Liguan.

But the news was not all good. The Marine right flank was hanging in the air with no connection with the Army’s 77th Infantry Division. Geiger and Turnage worried about their open flank.

However, the Japanese were close to the end of their tether. Their last attempt to hold off the Marines took place defending the Finegayan area, where they still had a few artillery pieces and good observation posts. Japanese shells could rain down on key American road junctions. On August 6, Turnage ordered his Marines to concentrate on the roads and trails. The Marines moved forward three miles and tied together their front lines.

The 1st Provisional Brigade took over the left flank of the Marines on August 7, with the 4th Marines heading north for Junction 460, four miles south of Ritidian Point, the northernmost part of Guam. The same day, the 3rd Marine Division advanced three miles on a northeastern axis.

Guam Secured

On August 8, Shepherd’s brigade resumed its advance at 7:30 am with the 22nd Marines on the left flank, moving cautiously behind destruction caused by Navy and Marine artillery. Company F of 2/22 reached the northern coastline of Guam first.

By August 9 and 10, the Japanese were taking refuge in the northeastern corner of the island, and the Americans were finding the pursuit of the enemy frustrating. They could not find five Japanese tanks that had broken into the lines of 2/3 on the night of August 8, which escaped completely and were likely abandoned.

On August 9, the Marines abandoned their final push into the northeast when they learned from Guamanians that 3,000 Japanese were in the area—this looked more like a job for Marine artillery. The heavy guns poured 4,000 rounds into the suspected area for 2½ hours.

While the Marines moved forward, so did the Army. Heavy Japanese defenses slowed the 77th Division’s reconnaissance company, so the 1/306 moved in on August 10 with greater firepower. The Americans brought up flamethrowers and were greeted with rifle and machine-gun fire, which killed eight and wounded 17 GIs. The Americans decided to wait for the next day to hit the Japanese with more force. On the 11th, the 1/306 attacked the trenches and caves with flamethrowers, mortars, and machine-gun fire.

At 11:30 am on August 10, Geiger announced that Guam was secure, just before a visit of Admirals Chester Nimitz and Raymond Spruance and Generals Vandegrift and Holland Smith, to see how the campaign was doing. Geiger could report that 10,984 Japanese bodies had been counted for a loss of 7,714 U.S. casualties. Of these, the Marines had suffered 1,190 killed, 377 dead of wounds, and 5,308 wounded. The Army had lost 177 killed and 662 wounded in its drive north.

Nevertheless, more than 7,000 Japanese troops were still hiding out in Guam’s bush, and while they presented no organized threat to the American forces, they were still capable of taking American lives.

The Last Japanese Soldier Surrenders

The island was taken over by Navy, Marine, and Army engineers, who created vast air and naval bases on a once neglected corner of America’s empire. Nimitz himself established the forward headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Fleet there. Vast fleets of B-29s roared from the Marianas to pulverize Japan’s cities. However, the struggle to secure the island continued for weeks.

The Americans gave diehard defenders a carrot-and-stick approach, dropping Japanese psychological warfare leaflets by day from the air, urging surrender. In August, U.S. patrols averaged 80 Japanese killed each day, and as late as February 1945, there were 141 killed that month with only 44 prisoners taken.

Incredibly, some Japanese hung on. A Major Sato and his 34 men operated in southern Guam all the way to June 11, 1945, when he finally surrendered. Takeda and a group of 67 men would not give in until September 4, 1945—two days after Japan’s surrender in Tokyo Bay.

Japanese holdouts across the refused to dishonor themselves by surrendering. In 1960, two fugitives, Tadeshi Ito and Bunzo Minegawa, surrendered. They helped local authorities scout for other holdouts but did not find any. It was presumed that Guam was finally liberated.

It was not.

On the night of January 24, 1972—28 years after Geiger had declared Guam secure—two Guamanian fishermen, Jesus Dueñas and Manuel De Gracia, headed out to check their shrimp traps along a small river near Talofofo. A skinny man charged out of the jungle. The two Guamanians subdued him. Once in the hands of Guamanian authorities, the man was identified as Sergeant Shoichi Yokoi of the 38th Infantry Regiment, officially listed as dead since 1955.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments