By Katrina Shawver

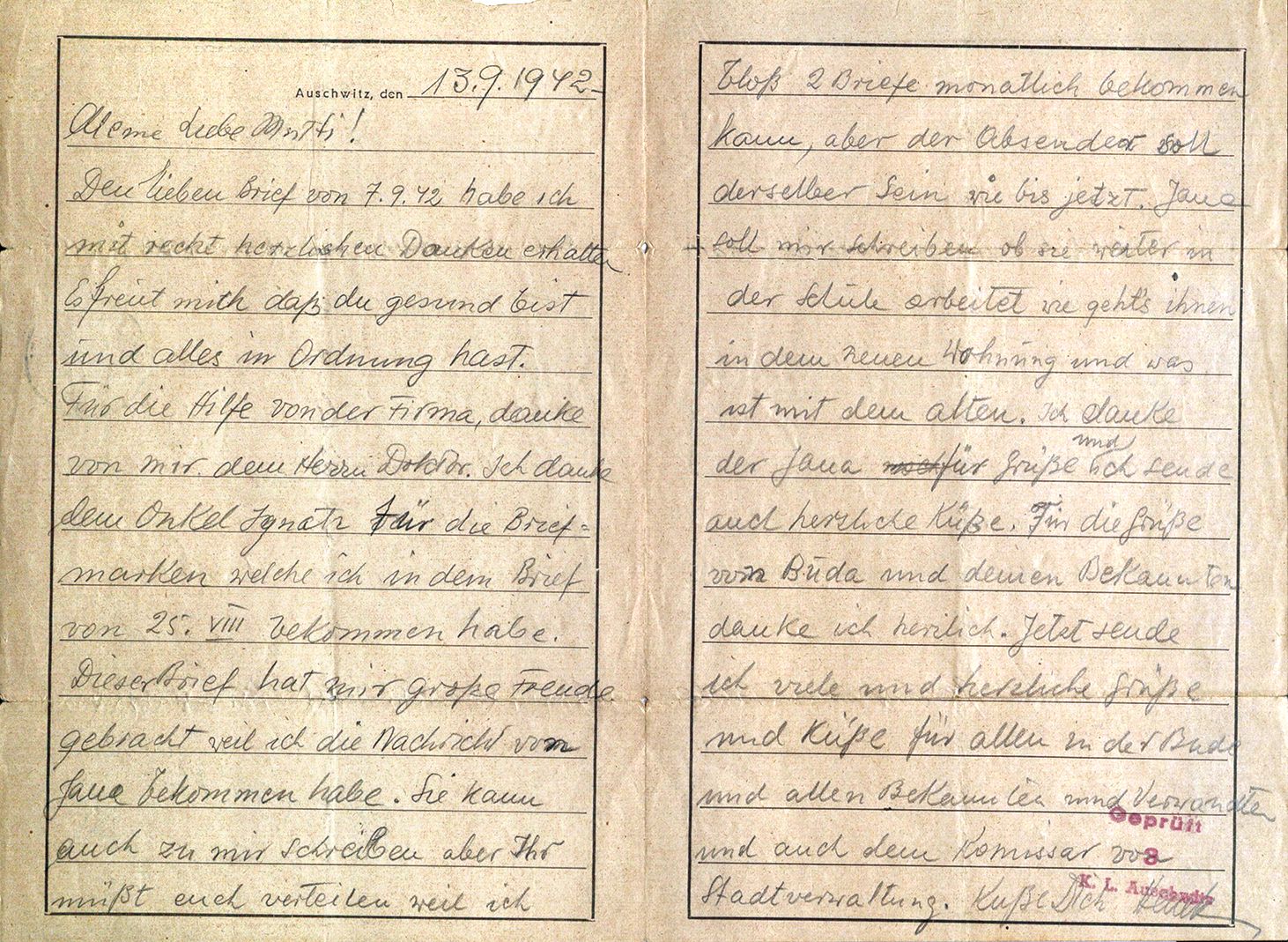

Henry Zguda, a Polish Catholic, spent three and a half years interned at Auschwitz and Buchenwald as a political prisoner. During a series of interviews held with Zguda in 2003, he shared his camp experiences, including a discussion of his camp letters. A study and translation of all his letters from both camps in combination with first-person interviews, offer an intriguing lens into prisoner mail, incoming packages and money practices in German concentration camps.

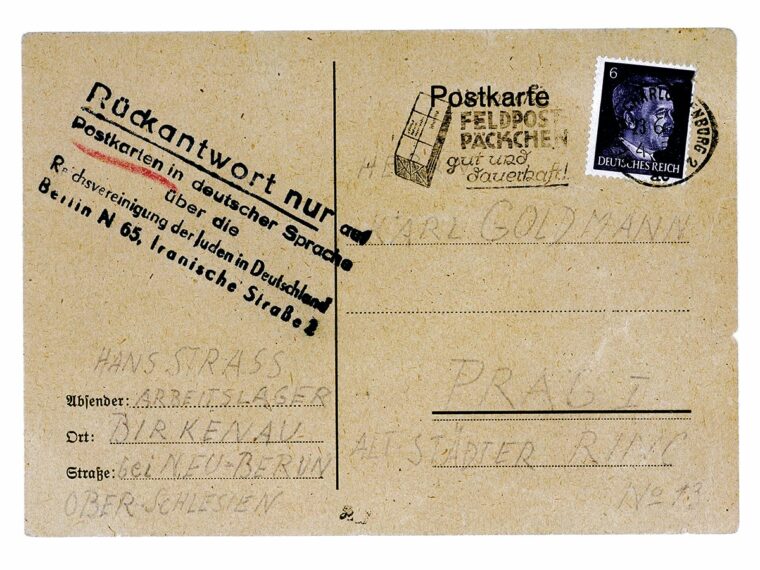

A postal station existed at every concentration camp, and each ran with surprising efficiency given the harsh conditions and intended short life span of all prisoners. Restrictions evolved as to who could send mail and what paper and envelopes could be used, especially in the first camps such as Dachau (1933). In the earlier years of Buchenwald a very few groups—primarily the privileged Dutch hostages—were permitted to receive packages from home in addition to letters. Camps subsequently developed standardized stationery that included pre-printed rules and limited the number of lines and space prisoners had to write.

The rules from Dachau, as the first camp, became the primary example. The stationery consisted of either a postcard or a single piece of paper that could be folded into a self-envelope. Small handwriting definitely ensured being able to send a longer message.

Jews and Soviet POWs occupied the lowest prisoner status in all camps and were rarely granted mail privileges. When Germans did grant mail privileges, especially for Jews, they weren’t being totally altruistic. The letters constituted a minor ruse for relatives that prisoners were merely at a “protective custody” camp and were treated better than they were. Camp commandants imposed varying rules on what had to be included or omitted. In Auschwitz, every letter had to include “I am healthy.” In Buchenwald, prisoners could never mention they were hungry. Then consider this phrase that appeared in the printed rules: “The sending of money is permitted.”

Families were encouraged to send funds as money orders on behalf of their family members. The Germans maintained scrupulous financial accounting of prisoner accounts and incoming funds, as demonstrated by multiple documents that record incoming deposits and disbursements. Among other financial needs, prisoners had to pay for the stamp on each letter. Even without money privileges, stamps were one of the few things permitted as an enclosure with incoming prisoner mail.

Prisoners were required to register a single address; all mail would hence be sent to that one individual. In some instances registering an address posed a serious dilemma. If prisoners had no family left at home, who did they address their mail to? Plus, prisoners didn’t know how much danger they risked in supplying a family member’s name and address to the Germans. Would that person be arrested?

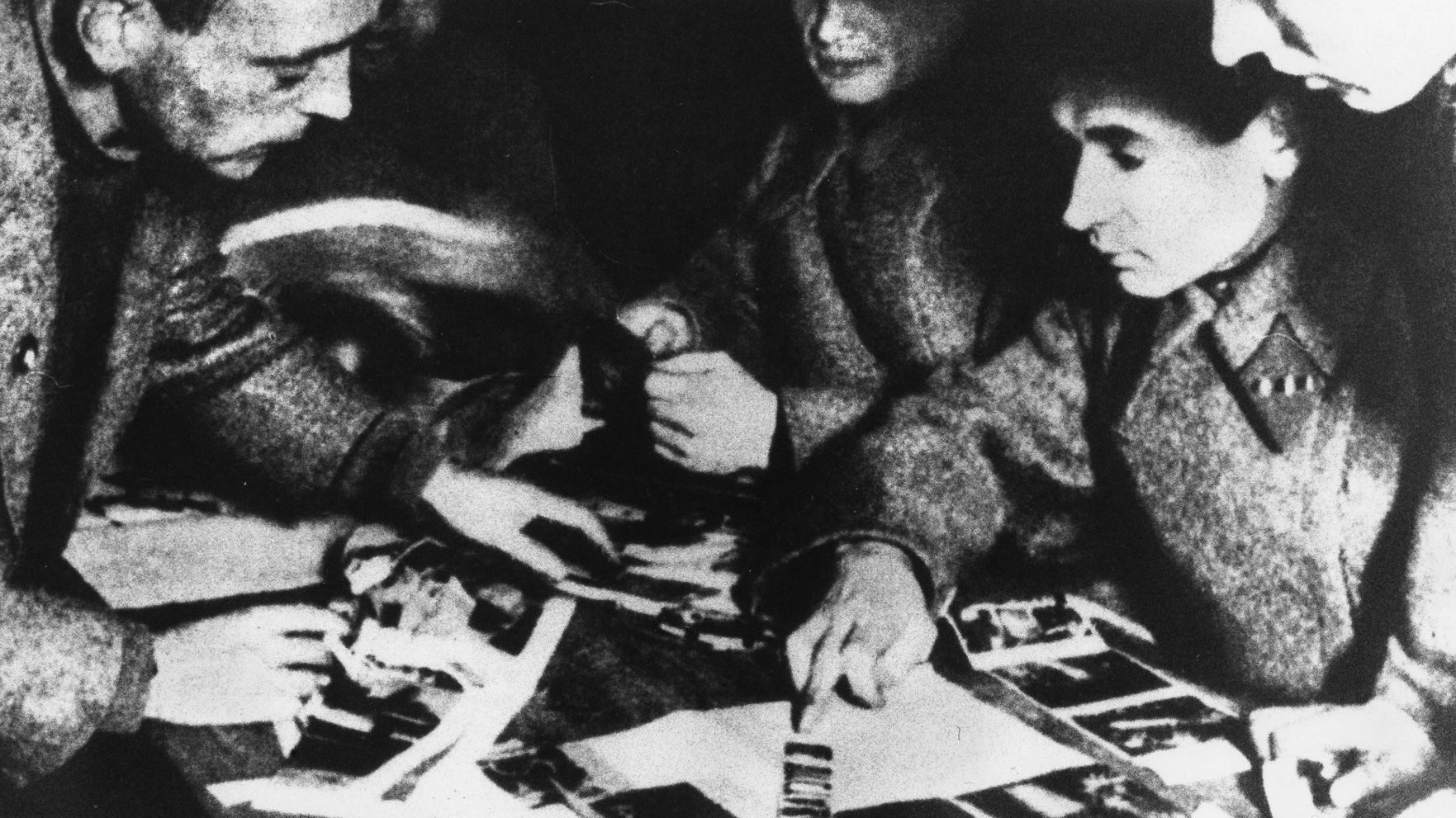

All correspondence had to be written legibly in German and pass through camp censors. Each censor had his own numbered stamp; once the letters were marked approved with the red Geprüft stamp they were mailed. The “official” frequency of mail permitted varied from twice a month to every six weeks, or randomly at the whim of the Germans.

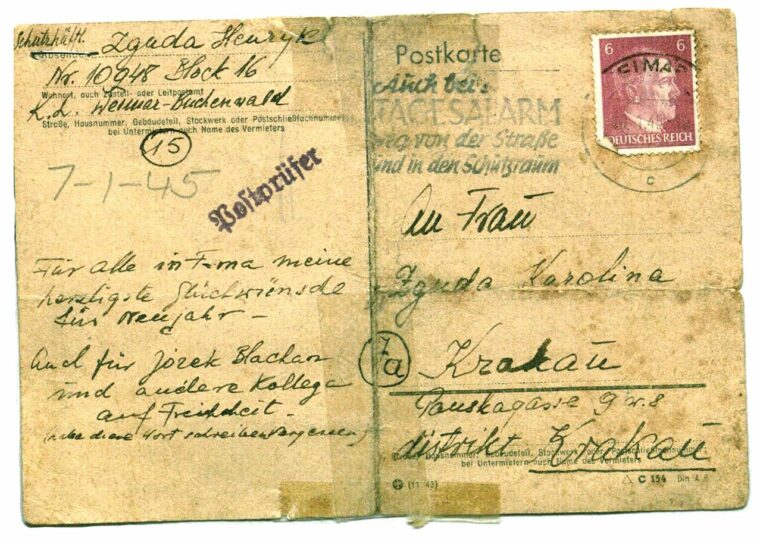

With mail, as in many other aspects of camp life, prisoners who spoke German were at a distinct advantage. They understood the block leaders’ orders, could get better work assignments, and had a chance to earn a precious piece of extra bread from non-German speaking prisoners in exchange for writing their letters. Because Zguda studied German in school for six years, he was able to communicate in simple sentences. All his mail was addressed to Karolina Zguda, Panska 9, Krakow, Poland. In addition to writing in German, he Germanized his letters to Frau Zguda, Panska Strasse, and General Government instead of Poland. He signed his letters Heinrich instead of his Polish name Henryk. Subsequently, some camp records read “Heinrich,” some read “Henryk.”

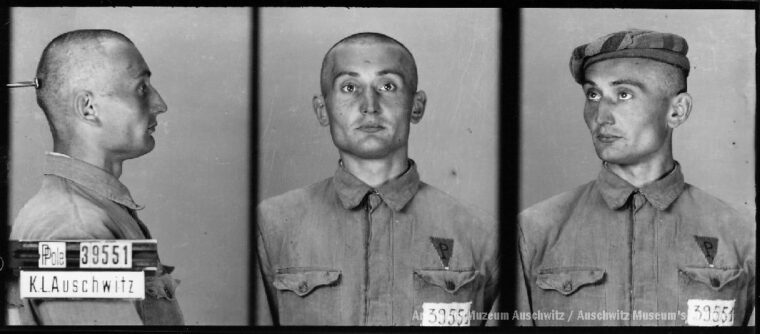

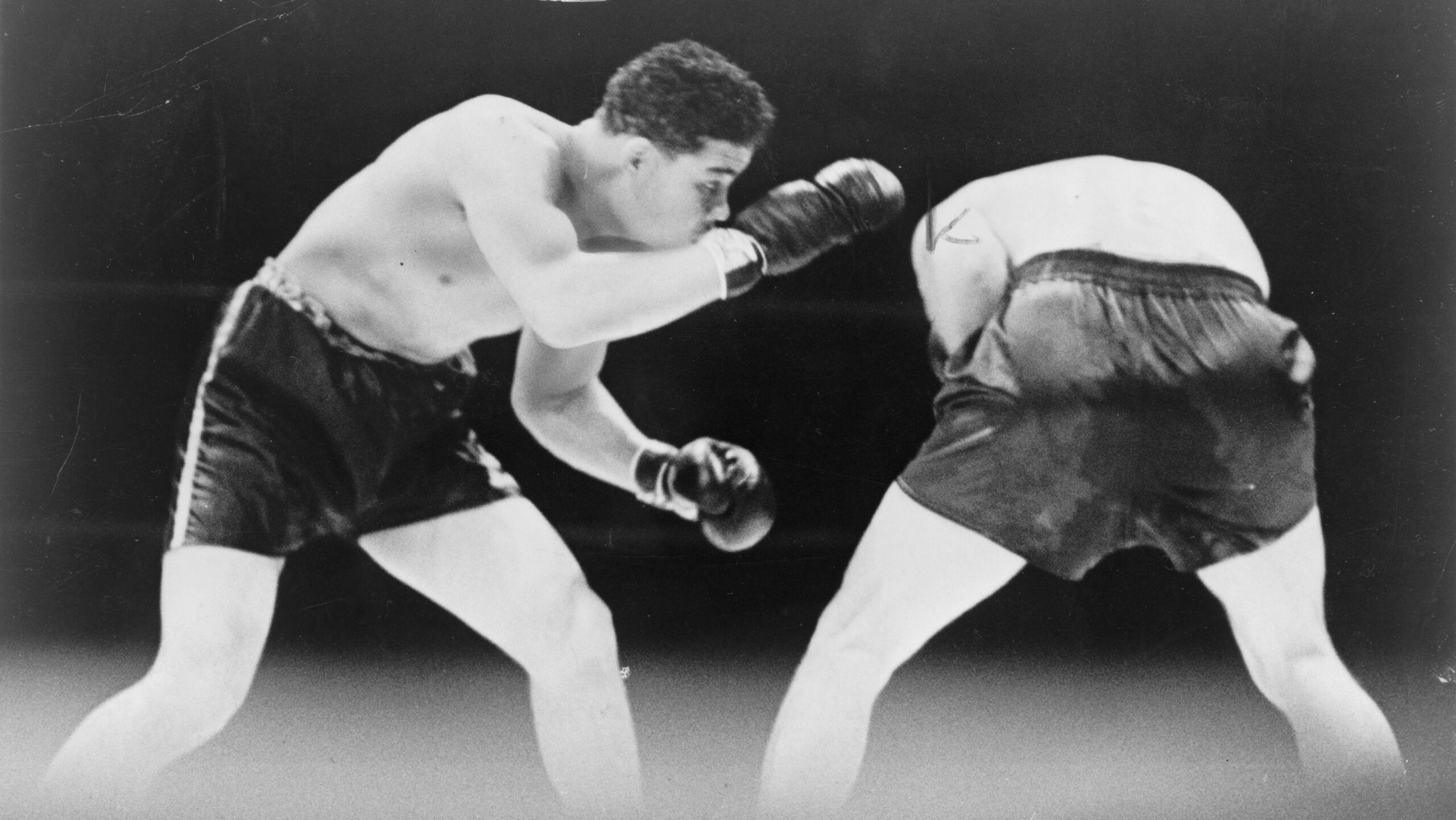

Zguda arrived at Konzentrations Lager (K.L.) Auschwitz on June 15, 1942, on a transport of 130 Poles from Montelupich Prison in Krakow. The 25-year-old athlete was registered, shaved, disinfected, and thrown a suit of blue-and-white striped clothes and a pair of crude wooden shoes. Next came three quick photos with his head shoved against a nail for positioning. A glance at the three-way photo shows an upside-down triangle with the letter “P” in the middle for Polish. Just as Jews were required to wear a yellow Star of David, the camps devised a quick identification system of colored triangles for different categories of prisoners. Henry wore red for “political prisoner.” Sadly, few who came on that transport with Zguda would survive the war.

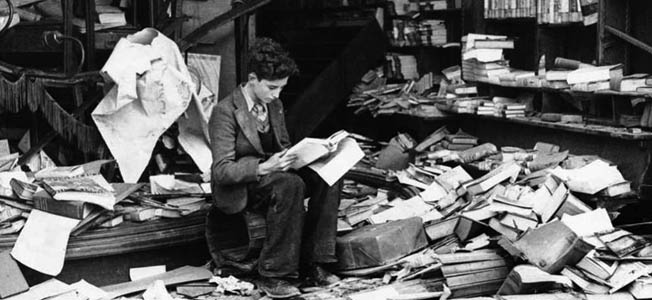

On a Sunday afternoon shortly after arrival, Zguda found himself in a large room of tables he sarcastically described as full of “300 guys and 10 pencils.” Since his arrest in Krakow on May 30, 1942, he had endured two weeks of interrogation and torture, lost several teeth and broken a finger. Additionally, he had recently received a series of hits on the buttocks splayed naked on a wooden stand built specifically for whipping prisoners.

He described the roughly scrawled letter he wrote that day as “total b.s.” All he could say was “I am healthy” and “I feel fine.” In reality, he wasn’t sure he would live to the next day. That first letter cost the already-starving Zguda a piece of bread to another prisoner for the red postage stamp emblazoned with the image of Hitler. In turn, his mother, who had little means of support, had to pay a translator for each letter she received. But thankfully, she knew he was alive and where he was, at least on the date the letter was written.

Auschwitz, June 28, 1942:

My dear mother!

Since June 10th I have been at the concentration camp at Auschwitz. I am notifying you that I am healthy. I hope that you are healthy as well. You should not worry yourself and cry but take care of yourself. I hope that you have enough money and food. If that’s not the case you can take from the money that is owed to me (undecipherable) like from Micia and (undecipherable.) My suit may be picked up from the tailor. (page is ripped). He lives on Zwierzynieckastrasse 7 or 8, his name is Wojtas. When you write pay attention to the instructions on the first page. Lastly I kiss you with love my dear mother, and also Ms. Jana. Kindest regards to all acquaintances and relatives and for all in Bude where I worked.

Heinrich

If prisoners were allowed to send mail, then it begs the question, could they receive mail? Yes. Of course, due to extremely harsh conditions any letter that a prisoner received in camp would be extremely rare. Today, a few exist in curated collections. In Zguda’s case, we have a good idea what he received, because in his subsequent letters he sent messages of thanks to multiple relatives for their letters and gifts. While outgoing mail was restricted to one address, Zguda regularly thanked multiple relatives for their incoming letters.

We know Henry’s mother received the first letter because in Henry’s second letter home, dated July 26, 1942, he wrote in part:

“My dear mother, I received your dear letter with many thanks. I am healthy and wish you the same from all my heart. I’m pleased that you took care of my things. I thank Uncle Ignatz for the postal stamps that I received and also Uncle Franz for the money he sent.”

The letter, continuing in a conversational tone, does not reflect Henry’s reality of sheer misery. During interviews he described himself as near death when he wrote this second letter. Any modern interpretation of camp correspondence needs to consider the standard censorship that prevented communicating real circumstances.

Based on Henry’s letters we know relatives sent funds to his account on multiple occasions. One Einzahlungsliste (deposit list) from Auschwitz for October 23, 1942, shows Heinrich Zguda receiving 10 Reichsmarks. Zguda’s letters indicate other receipts of money, but only this list remains.

In their haste to evacuate Auschwitz in January 1945, the Nazis destroyed records so that remaining records and photos constitute only a partial set. No actual currency was ever given to prisoners; the amount was deducted from their accounts for items such as stamps and stationery. Germans were notorious for pilfering money and goods from incoming prisoners and Jews; whether the 10 Reichsmarks is actually what was sent is unknown.

In Henry Zguda’s third letter home, dated August 16, 1942, he wrote in part:

“My dear Mother, I thankfully received your letter from August 11th. I worry about you and your health. I already asked you to not worry because I am very healthy. Only thoughts of you cause me pain.”

Later in the letter he advised his mother to collect on his debts and sell his things so an uncle could send the funds to his account. Apparently Henry said something wrong, as the censor crossed out two lines before approving this letter. Other letters from Auschwitz dated August through November 1942, all contain similar messages written as light conversation.

In November 1942, Auschwitz began allowing prisoners to receive packages from home. The printed text includes the words, “Packages may not be sent” and some historians incorrectly state that was the case. But if the Germans made the rules, the Germans could change the rules. Receiving a food parcel from home greatly increased the prisoners’ ability and will to survive. Packages generally included foodstuffs and other precious commodities that could be used to barter for bread or bribe a guard.

Henry described a Christmas package from his mother as having Christmas cookies and a pair of thick knitted socks, complete with a small ball of yarn and darning needle for repairs. Food and a pair of warm socks in a bitter Polish winter would have been like receiving gold. Henry always shared what he received with his friends, even if it meant only handing over the wrapping from the cookies so someone could lick the crumbs. In Henry’s last letter from Auschwitz he thanked five different people for their packages at Christmas.

Auschwitz, January 10, 1943:

My dear mother!

I already received your letter from December 8. Every message from you makes me really happy. It saddens me that you still have to work so hard, and have great sympathy for M. Różycka. I’m healthy and also feel well. Heartfelt thanks for the sent packages, but I don’t know whether sending them is burdensome to you (all) and maybe they don’t send those packages so often. The first package was from Uncle Ignatz, then from Mrs. Zosia, then from Aunt Antonia, from Uncle Franz and from you, dear mother. Before Uncle Franz sent me a postcard for which I give heartfelt thanks. I send you (all) best wishes for New Years. I also send for all in Buda kind regards. I kiss you a thousand times my dear mother and all relatives and acquaintances.

Your loving son, Heinrich

If reference materials communicate the facts and rules of receiving a package from home, personal accounts and memoirs convey the raw circumstances and value. John Wiernicki, another Polish political prisoner, No. 150302 in Auschwitz II-Birkenau, describes receiving packages from home in his memoir War in the Shadow of Auschwitz, Memoirs of a Polish Resistance Fighter and Survivor of the Death Camps.

“I learned from Toni that twice a month, non-Jewish prisoners were allowed to write letters home…the mandatory sentence in German I am well and happy…The first parcel arrived four weeks later. In a brown cardboard box, opened previously by the censors, I found bread, fat, sausage, and a small cake. Food from home was a ray of hope, a sign of independence…One could buy everything from underwear to gold watches for a small portion of homemade bread.”

Wiernicki later obtained warm underwear in exchange for his grandmother’s butter. When he became ill, he gained admission to the infirmary with a bribe of one pound of his grandmother’s bacon. He took his valuable, bulky brown parcel of food with him to the infirmary and hung on to it for dear life, keeping it under his pillow at night. He later bought the right to his own bed for a half pound of butter.

Just as outgoing mail was censored, incoming mail packages were opened and searched. Germans kept the best items for themselves and their families. There are countless stories of Germans sending home large packages filled with items stolen from incoming Jews and prisoner packages.

Auschwitz I was the site of a Polish army camp 30 minutes outside Krakow, and initially used as a “protective custody” camp for Polish political prisoners beginning in May 1940. Few people realize that Catholic Poles, priests and the Polish intelligentsia were the first and majority of prisoners held there for the first two years of the camp’s existence. As an example, before Auschwitz opened, on November 6, 1939, the Nazis called a meeting of professors at Jagiellonian University in Krakow. All 183 present were arrested and sent to K.L. Sachsenhausen, where they perished in the bitterly cold winter. The first mass Jewish transport did not arrive until February 15, 1942. Two social realities resulted: the two primary languages spoken in camp were Polish and German, and Poles rose quickly in camp hierarchy as they were there first and filled needed positions. They then subsequently helped their fellow Poles rise through the ranks and attain better jobs. A significant Polish underground developed to help whomever they could.

In 1943, orders came down for most of the Poles in Auschwitz to be transported to other camps in Germany. The orders accomplished two things. First, after high-ranking German officials met on January 20, 1942, in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee, and devised a plan to exterminate all the Jews in Europe, Auschwitz had been designated the primary killing center for European Jewry. The Germans needed room for more incoming Jews. Equally important, the Germans were aware of a strong Polish underground. They used the opportunity to disperse large groups of Poles to different camps such as Buchenwald, Mauthausen, Neuengamme, and Dachau deep in Germany.

On March 10, 1943, a transport of 1,000 Poles left Auschwitz headed west. Henry described the smell of the slop bucket in the dank corner swishing and overflowing and how prisoners peered out the high train windows to try and determine the train’s destination. A turn south meant Dachau or Mauthausen; a turn north meant Sachsenhausen or Neuengamme, directly west meant Buchenwald. Of the possible camps, Buchenwald was by far the “preferred” camp for political prisoners, if such a thing could be said about a concentration camp. Through underground connections, Henry’s name landed on the Buchenwald transport list.

In many ways, the camp could be considered an SS suburb of Weimar, so close were the connections with townspeople. Once prisoners arrived at the Weimar train station they were marched past townspeople and forced to run uphill amid shouting guards and snapping dogs. Today the road is known as Blutstrasse, or “Blood Road,” both for the number of prisoners who died building the road and for the brutal trip up the hill. It remains the only road to the camp.

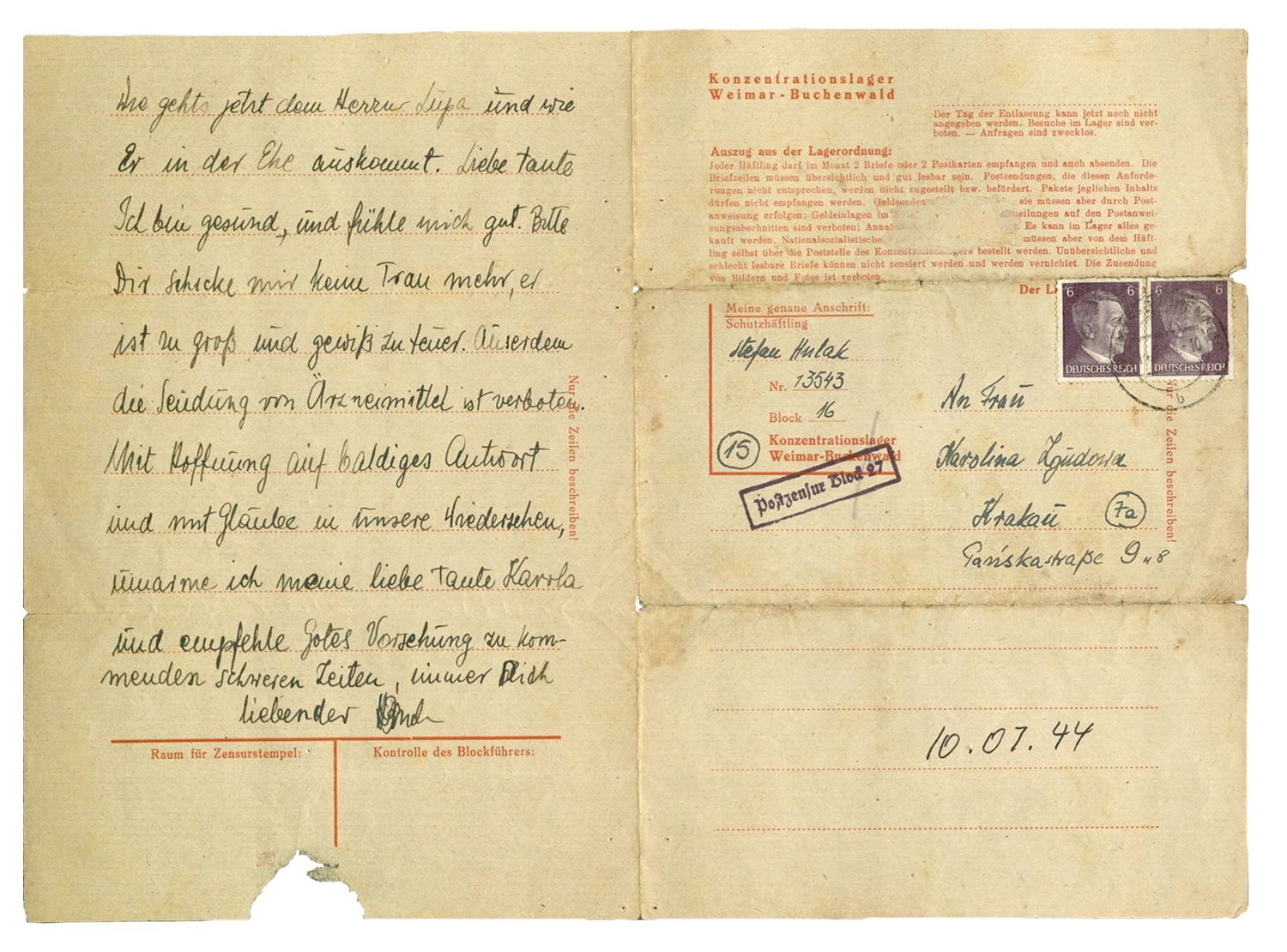

Presuming all 1,000 Poles in Zguda’s transport were registered with the same paperwork as Henry, there was a lot of information to enter both by hand and typewriter. Instead of a folder, the camp used a Buchenwald Individual Documents envelope to hold and file various prisoner records. Henry’s envelope included a prisoner registration card, a personal effects card, an office card, two prisoner questionnaires, a medical registration card, an employment card, a prisoner number card and a postal control card. The copy of Zguda’s postal control card is undated, but documents incoming mail on August 6 and September 29, and outgoing mail on August 15 and September 26. This mail could be for either 1943 or 1944, based on his camp dates.

Two other pages revealed a surprising discovery. Funds in prisoner accounts followed prisoners from one camp to another. With classic German efficiency, one list documented the transfer of 25 Reichsmarks; a second list documented the transfer of 275 Polish zlotys. Both are dated the same date as transport, March 10, 1943, and are listed in order of Auschwitz prisoner number 39551 with his new Buchenwald number 10948 notated next to his name.

Henry said, “Buchenwald was a paradise compared to Auschwitz.” History, facts and staff at Buchenwald support his statement; the term “paradise” of course being compared to the hell of Auschwitz, not normal life. Buchenwald was the only concentration camp where the original political prisoners, in this case the communists, had so much power delegated to them. The German communists were there first in 1937; some had been in “protective custody” since 1933. They rose to high positions and kept their people in line.

When Henry arrived in Buchenwald, he recognized a friend from Krakow. This friend introduced Henry to the right camp leaders; as a friend of the communists he stayed relatively safe. Through these connections he was able to attain a better work command, which also kept him in good standing for mail privileges and packages.

Henry had saved more letters for his nine months in Auschwitz, than for his two and a half years in Buchenwald. The fragile documents exist because Henry’s mother kept them, and he subsequently saved them for his entire life. There exist only two letters and two postcards for his time in Buchenwald; two date from 1944, one from January 1945, and one in very poor condition dated June 27 with the year missing. Whether it was sent on June 27, 1943 or 1944, it is the first letter of record from Henry. I don’t know if it’s because that’s all he sent, or if that’s all that survived. Based on their content and other dates noted on his postal card, I believe there were more.

The letters that were saved indicated quite a few incoming packages for an unknown time span. On one postcard, a stamp read: ich darf alle 6 wochen elne; Karte Schreiben und empfangen: “I may write and receive every six weeks.” In one letter to his mother, Henry instructed her, “…you can send one package a month.” As with any rules, Germans could suspend mail privileges or capriciously change the amount of mail allowed. Interestingly, the Buchenwald letters are more legible because they appear to be written in ink. The Auschwitz letters were written in pencil, as were letters from many other camps. Logically, after decades pencil script is far more faded than ink.

Like the Auschwitz letters, the Buchenwald letters mentioned receiving letters and the contents of various packages. Items in huge demand included cigarettes, bacon or fat, tea, and chocolate. Henry also asked for and received toothpaste and shoe polish. When I asked him quizzically about the shoe polish, his answer was simple. “The Germans like it clean. The cleaner you are the longer you live.” Shoe polish could be traded with those in higher positions for food and other valuable commodities. Like all prisoners, survival remained the ultimate goal for Henry.

Buchenwald, June 26:

Dear mother!

I am (XX) healthy X always XXX as long as I receive no news from you. Last? letter ha?? I received May 24 and the packages with X shoes and medicines. I’m happy X X that you think of me, that was a nice surprise. On May 23 I received a package with bread, June 12 one with cigarettes, June 8 one with onions and today I got a package with slippers, fat, and medicines, but still no letter. Dear mother, you surely must have trouble getting groceries, you can send one package a month. That would be good too. Now you have to think more about yourself. Many thanks for the greetings from the firm and I hope that finally one of my colleagues from the firm writes to me, or Rachniowski. Greetings for uncle in Sosnowitz, all relatives and acquaintances. Well I kiss you dearly dear mother.

Your X loving son Heinrich

The Buchenwald letter dated July 10, 1944 is addressed, “Dear Aunt!” and was sent from Stefan Hulak, prisoner no. 13543, also of Block 16. Zguda explained that by that day he had used his quota of letters for the month. Hulak, a fellow prisoner in Block 16, agreed to write a letter for him. I recognize the names as Henry’s friends and relatives, so Zguda clearly dictated it to Hulak.

Buchenwald, July 10th, 1944:

Dear Aunt!

I’ve thankfully received your letter on July 1. I’m happy that everything is well with you all and also that Ryska wrote. I was anxious to know what is going on with her. I am writing this letter in hopes for a better future and that you survive all difficulties. July 9th I received two packages from Wróblik and Rozwad. From Wróblik butter and cake. Write to Rozwad that I received 10 marks. I ask them to package the products better, because everything was mixed together. I thank them for everything dearly. Great thanks to Uncle Franz for the two packages and for Janka, 20 Rmk have already been deposited in my account. I received everything from you in good order, cod liver oil (I’ve already drank it) and marmalades (2 of them) didn’t leak. Thank you for the socks, but I don’t need any more socks and underwear, don’t send those anymore. The slippers brought me much joy, they fit really well. But also don’t buy such expensive things in the future. For Mrs. Genia many thanks from me, and apologies for the worries. How is Mr. Lupa now and how is wedded-life for him. Dear aunt I am healthy and feel well. I ask you to not send any more cod-liver oil, it’s too big and certainly too expensive. Regardless, the sending of medicines is prohibited. With hopes for a quick reply and with belief that we’ll see each other, I embrace you my dear aunt Karola and ask for God’s providence in the nearing difficult times,

Your eternally loving, (scribble)

In the fall of 1943, the SS introduced special scrip, intended as work bonuses to motivate prisoners for higher production. Multiple documents with Zguda’s name record daily work statistics for each commando. All indications are that the plan failed miserably. Very little that came out of the armaments factory at Buchenwald ever functioned. Money was handed out in scrip form that could be used at the puffhaus (bordello) or in the camp canteen where prisoners could purchase stamps, stationery, and mostly rotten food.

In Buchenwald prisoners could pay to see movies shown in a large “cinema barrack” where sports events, theater performances and band concerts also took place. Movies, of course, were always in German. Zguda specifically remembered one movie he saw at Buchenwald, “Stern von Rio.”

When the Americans bombed Buchenwald on August 24, 1944, they targeted the Administration building, the SS living quarters, and the armaments factory where prisoners worked. There was an unconfirmed report that at one point in the summer of 1944 mail privileges were suspended around the time of the bombing. A letter dated January 10, 1945, remains Henry’s last known correspondence from Buchenwald. In it Zguda thanks relatives for their packages.

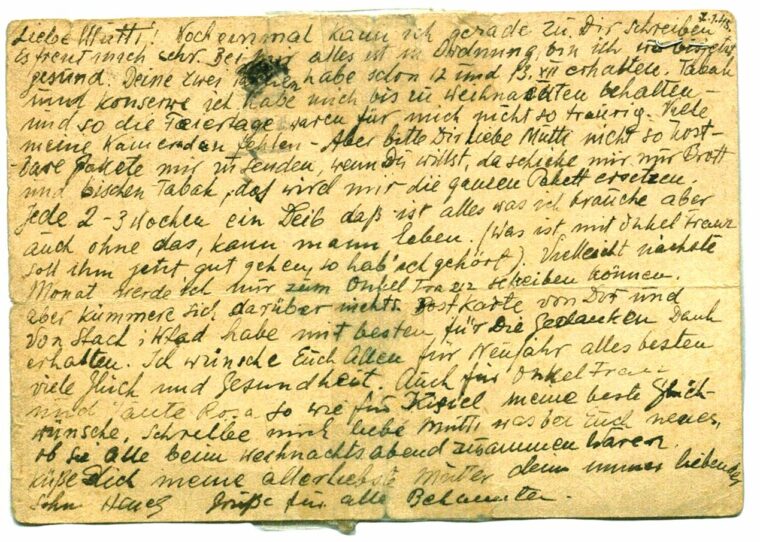

Buchenwald, January 7, 1945:

My dear mother,

Once again, I can write to you now. It brings me joy. All is in order here…and I am healthy. I received your two packages on December 12 and 13. The tobacco and conserves I kept until Christmas and so the holidays were not as sad. Many of my comrades are missing—But please, dear Mother, don’t send me such expensive packages. If you want, send bread and a little tobacco. Every 2-3 weeks a loaf of bread is all I need but I can live without that as well. (What is going on with Uncle Franz, I hear he is doing well). Maybe next month I will be able to write Uncle Franz. But don’t worry about that. I gratefully received your postcard and XX. I wish you all much luck and health for the New Year. Write me, dear Mother, about what is new and if all were together Christmas Eve. Kissing you my dearest Mother, Your forever loving son. Heinrich.

Greetings for all acquaintances.

By late spring, as the Americans drew closer, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler, head of the dreaded SS, gave the order to evacuate Buchenwald. In April, approximately 28,000 inmates were ordered on death marches out of Buchenwald. Zguda had to decide: Go? Or hide in camp and stay? Henry talked with his friends and he chose to “go be liberated.” He left the camp on April 10, for what would become a two-week death march. An estimated 12,000 people died on those marches. The first two American tanks reached Buchenwald on April 11.

Henry reached Dachau on April 27, practically dead from typhus and malnutrition. Two days later, as he lay dehydrated on a bunk his friends had dragged him to, he looked out his window and saw the Americans approaching. His last letter home is dated May 3, 1945. For the first time in three and a half years, he could write in Polish and say what he chose.

Dachau, May 3, 1945:

Beloved mother,

Finally the bell of freedom tolls for me. After sufferings that cannot be described on April 29 at 5 o’clock we were liberated by the US Army. Our joy cannot be put into words.

We marched by foot from Buchenwald to Flossenbürg near Weiden (Bayerische Ostmark) from April 10 to April 15. From there after 5 days we kept walking further, under the guns of bandits dressed as SS, till we reached Dachau. It was truly a march of death; thousands died. The rest of us got to Dachau, where after a couple of days of uncertainty the freedom had come.

I am extremely exhausted and ill, but happy. My feet are completely swollen but the life, which is coming back to normal in the camp, gives the hope for a happy ending. At this point I am writing to you only that, to my surprise, I am alive and I am waiting to see what happens next (what fate has reserved for me.)

We will be staying here for the next 3-4 weeks, after that we will go either home or to France. Thus don’t worry about me, beloved mother, we should see each other soon. [You] May have already heard from the radio about Dachau and its liberation. There are thousands of us here, and the food is getting better and better. I am feeling terrible, exhausted, my stomach is sick with diarrhea from dirty water, but day after day I am doing better. I am so happy that is over, if Doctor K or Genia could help through the Red Cross to pull me out of here earlier, I would be very grateful, maybe through someone from France or America.

Look up and down and ask people about this. Big hug, dearest mother.

Your son, Henry

The letters written by Henry express his hopefulness for a day of liberation, which, in fact, did come. They offer a glimpse of life as a political prisoner of the Nazis. Meanwhile, it is remarkable in itself that Henry survived. So many perished at the hands of their brutal captors during the Nazi era.

Katrina Shawver is a legal assistant and blogger in Phoenix Arizona. She has visited both Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments