By Robert Suhr

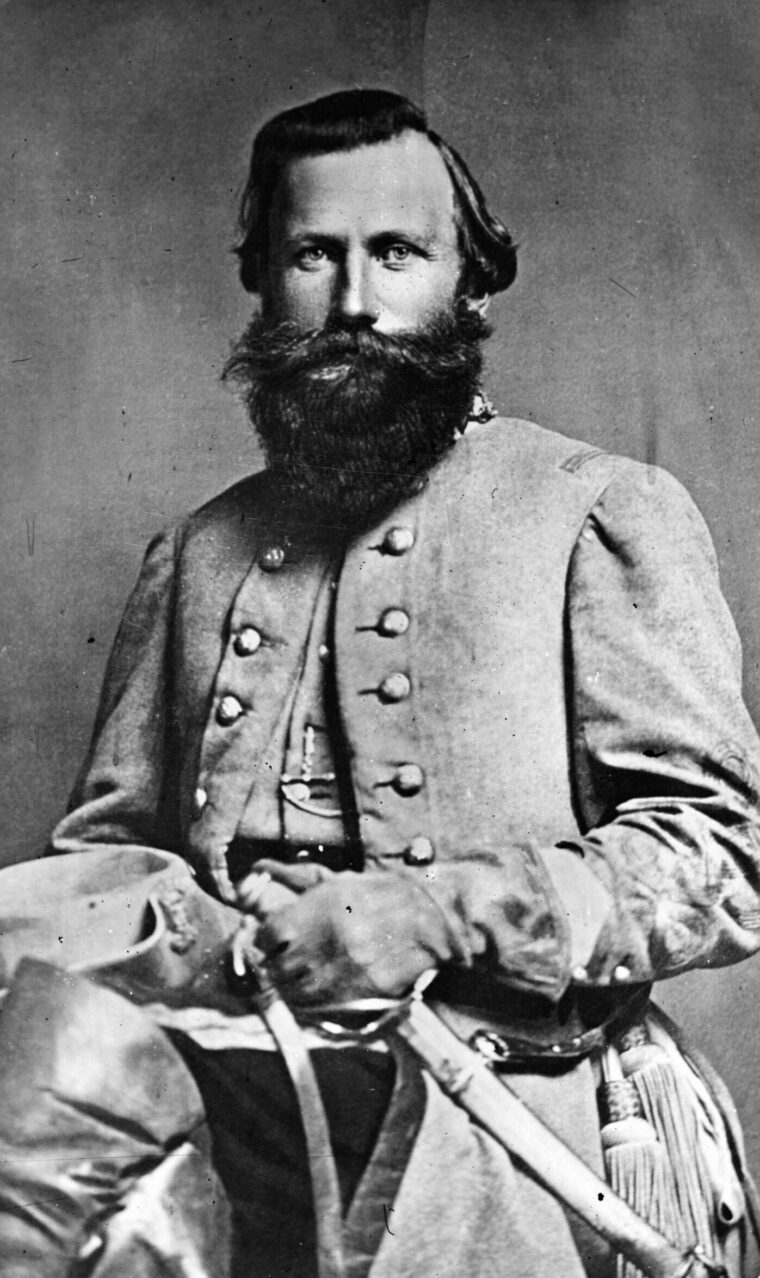

In early October 1863, three months after the setback at Gettysburg, three months after Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart was rebuked by his esteemed superior Robert E. Lee for lapses that led to the repulse on the bloody Pennsylvania battlefield, the colorful Southern horseman was ready to lead his cavalry corps to the kind of glory he knew it was capable. Standing in his way, however, was a reorganized corps of Union cavalry that was larger and better equipped than ever before. And the Federal generals were sharper than those whom Stuart had humiliated early in the war.

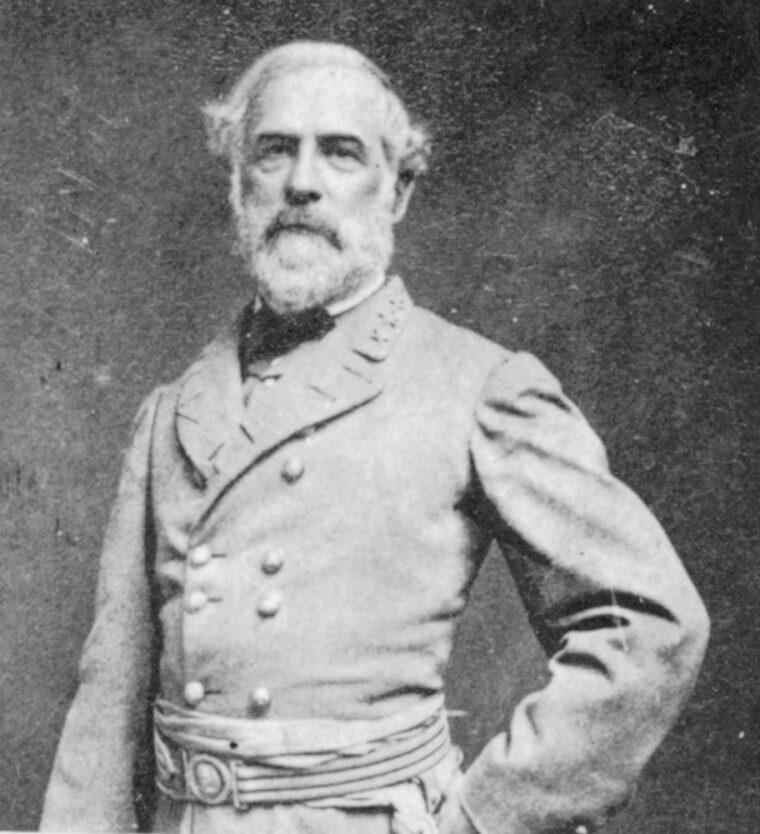

That month, the Army of Northern Virginia was about to go on the offensive for the last time. But to have success against an opponent that was 60 percent larger, Lee needed to move his army into position without being seen. Lee made Stuart responsible for screening the movement.

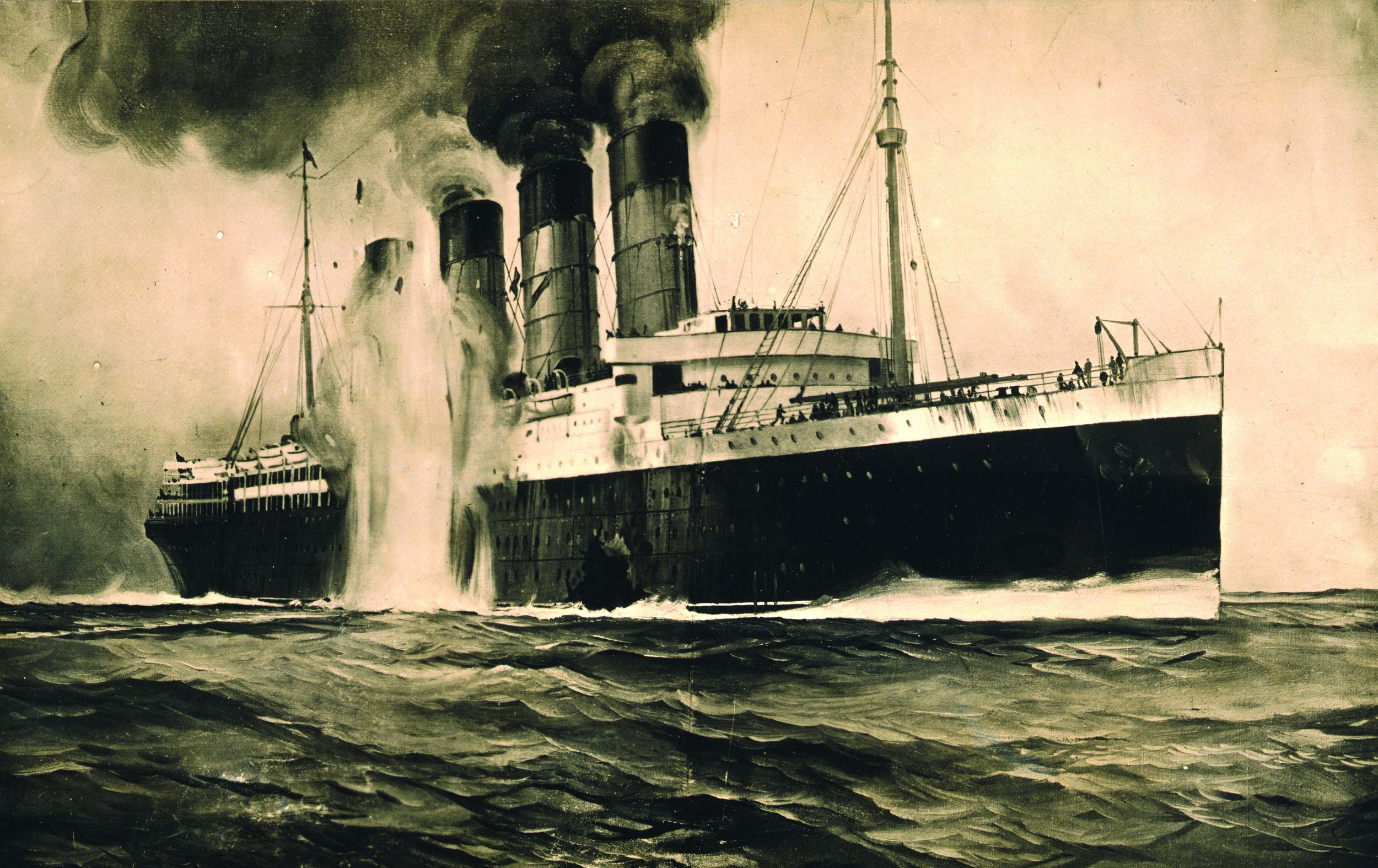

In September, both had armies send large numbers of men west. The I Corps of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, Lee’s “Old Warhorse,” went first. Its arrival at Chickamauga Creek helped the Confederate Army of Tennessee win a major victory there, pushing the Federals back into Chattanooga.

North of the Rappahannock River, Maj. Gen. George Meade learned almost immediately that Confederate troops had boarded trains heading south toward Richmond. He could not tell if they were going south to help defend Charleston, South Carolina, or eventually west to help the Army of Tennessee. A reconnaissance in force in mid-September by his entire cavalry corps revealed that Lee had withdrawn his army south across the Rapidan River.

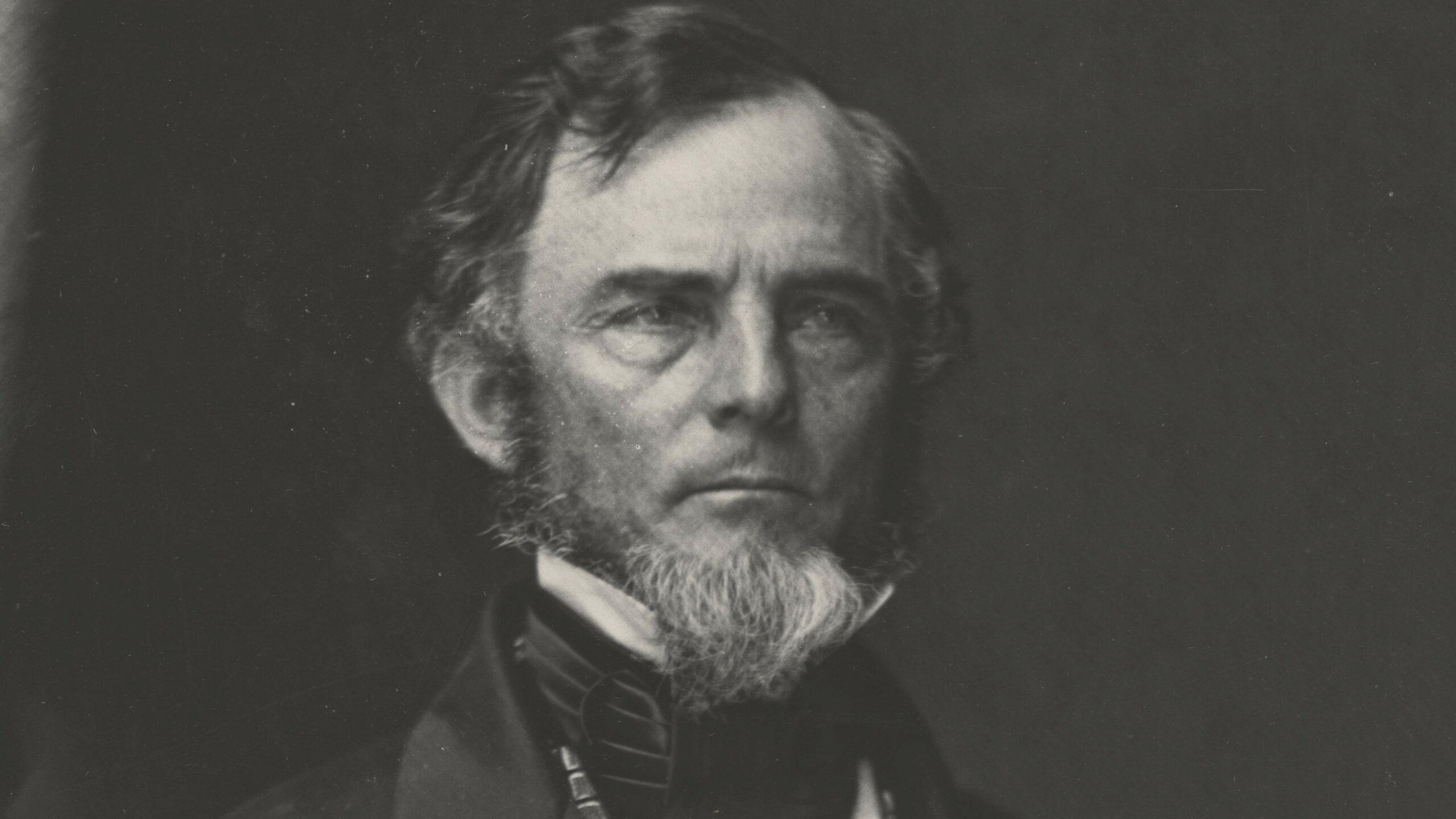

Convinced that a large part of the Confederate army had departed, Meade looked for a way to turn either Confederate flank. As he made plans to attack, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered him to send two infantry corps west to help the beleaguered Army of Tennessee under siege in Chattanooga. Meade dutifully obeyed. But with his own army now smaller, Meade suspended any plans to advance.

Lee immediately learned of the departure of the Union troops. Within a couple of weeks he was ready to take advantage of Meade’s timidity by launching an attack on the Union right flank. Lee wanted to repeat his greatest triumphs: Second Manassas and Chancellorsville. He would use part of his army to hold the enemy in place while the remainder delivered a knockout blow to a flank.

His enemy, the Army of the Potomac, was in bivouac in three groups. The bulk of the army, the II, III and V Corps, were on a ridge near Culpeper Court House. Meade had the I and VI Corps in advanced positions, each corps 10 miles from the main force. The I Corps guarded Morton’s Ford on the Rapidan River while the VI Corps protected the signal station at Cedar Mountain about 10 miles west.

Lee saw the signal stations on Cedar and Thoroughfare mountains as the principal obstacle to a surprise attack. From these points, Union signal officers could observe the Confederate army. To keep them from seeing Lee’s intended movement, the army had to march in a long, circuitous route through Madison Court House.

Of course, there was another way for the Federals to discover the Confederate’s march: wide-ranging Union cavalry patrols. To prohibit Federal cavalry scouting that could tip off Meade, Lee ordered Stuart to protect the line of march with his cavalry and to conceal it from Union intelligence.

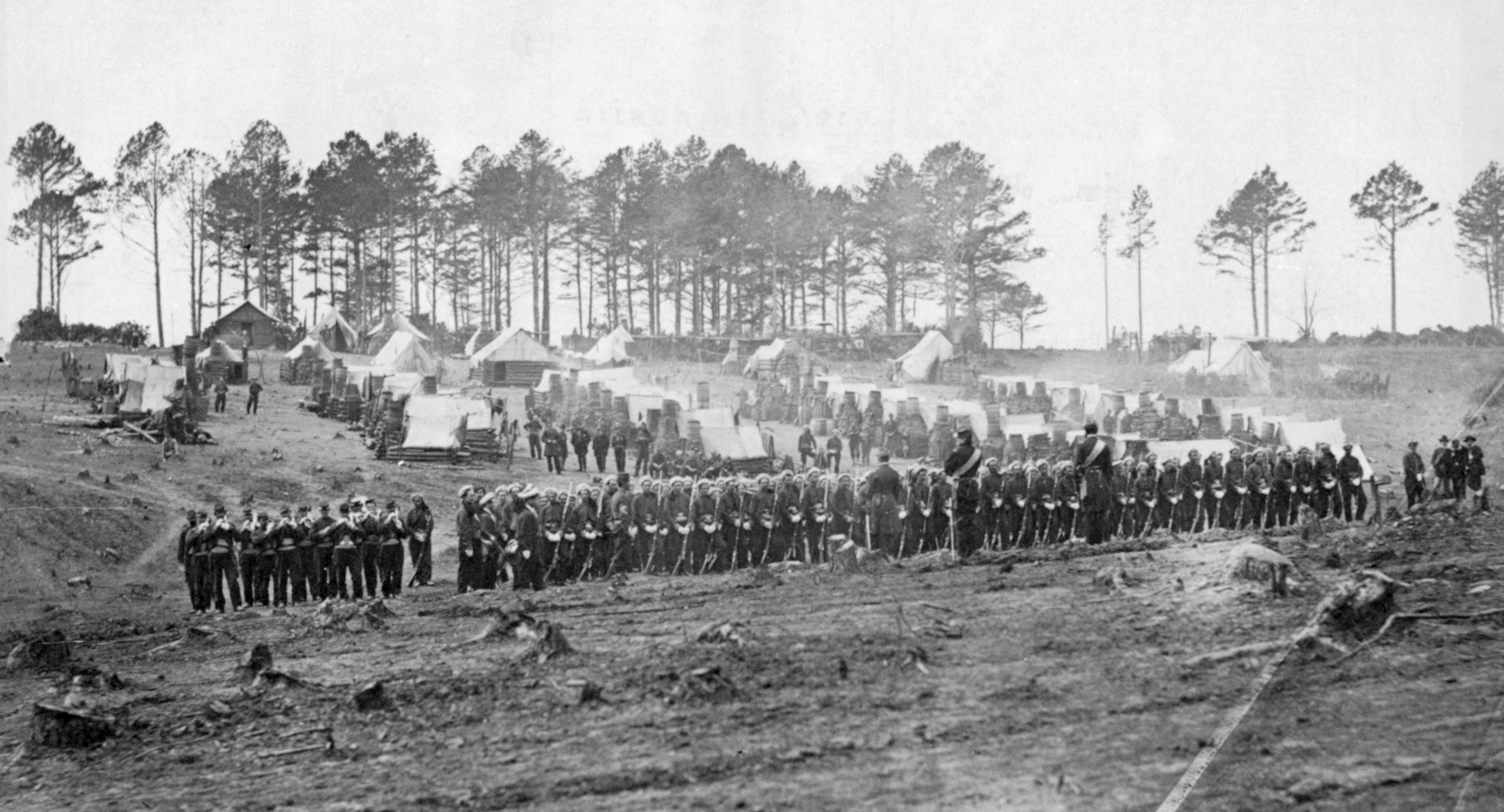

In September, Lee had authorized Stuart to reorganize the cavalry corps into two divisions, one under Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton and the other under Lee’s nephew, Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee. Because Hampton was still recovering from the wound he suffered at Gettysburg, Stuart personally commanded his division. Additionally, many of the brigades had temporary commanders because their generals had been wounded in fighting during the summer.

Stuart ordered Lieutenant Colonel Funsten with Jones’s brigade of Hampton’s division to screen the advance of the infantry. Butler’s brigade, under Col. Pierce Young, and Brig. Gen. James Gordon’s brigade, would protect the right flank. To protect the left flank, he ordered Brig. Gen. John Imboden to move down the Shenandoah Valley with his brigade, seizing the passes through the Blue Ridge Mountains as he advanced.

Fitzhugh Lee’s division had the responsibility of making the Union scouts think Lee’s entire army remained behind the Rapidan River. At Second Manassas, Lee had used Jackson’s corps to hold the Union army in position while Longstreet’s corps delivered a crushing attack on the left flank. At Chancellorsville, he had used Anderson’s and McLaw’s divisions of Longstreet’s corps to accomplish the same ruse while Stonewall Jackson took three divisions of his corps around to attack the Union right flank. No longer having the manpower to create a diversion on that scale, he delegated the job of decoying the Union army to Fitz Lee’s cavalry division (with support from Brig. Gen. Robert Johnston’s infantry brigade).

Lee needed surprise to be successful, but Meade knew something was afoot as soon as Lee began issuing orders. Around the beginning of October, Union signal officers broke the code used by their counterparts, enabling them to read messages from the Confederate signal station on Clark’s Mountain.

On October 7, intercepted messages suggested a cavalry movement toward the Union right. “General R. E. Lee: Send me some good guides for country between Madison Courthouse and Woodpile. Stuart, General.” Another message directed Fitz Lee to draw three days’ rations of bacon and hard bread.

From these messages, Meade decided the Confederates were about to make a cavalry raid about his right beginning October 8. He was convinced Lee intended to fall back on the defenses of Richmond and a cavalry raid would be a feint to distract him during the withdrawal.

On the 8th, Union pickets began reporting the movement of the Confederate infantry. One division commander reported to Meade: “The lookout on my left reports that about 2 o’clock this p.m. the enemy’s camp opposite my left was broken up, and that the troops moved in the direction of Raccoon Ford.”

To see for themselves what was happening, Meade and his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Andrew Humphreys, rode to Cedar Mountain to look at a pass through Southwest Mountain. Before they left, they saw a column of cavalry and infantry moving in the direction of Madison Court House.

As Lee maneuvered his forces toward the Union right flank, Meade placed parts of his army in increased jeopardy. He decided to threaten an attack across the Rapidan River by having the V Corps move up near the I Corps at Morton’s Ford. The V Corps was to remain hidden in the woods while the I Corps crossed the Rapidan River to seize the heights on the south bank.

He ordered Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick to move his VI Corps across the river when he thought best.

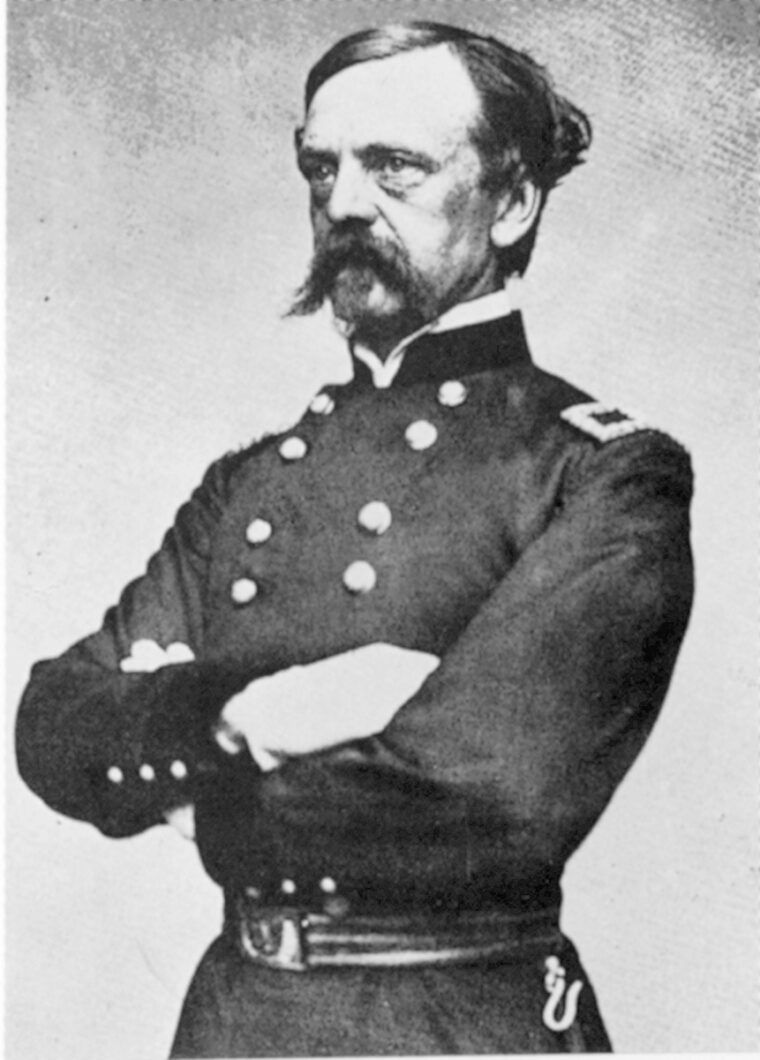

Meade’s primary defense would be provided by his cavalry corps, but he was at a disadvantage as a result of his own policy. Meade considered the commander of his cavalry corps, Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, to be a staff officer. As such, he wanted Pleasonton to remain at headquarters. This forced the Union cavalry divisions to operate in the field as separate commands.

Pleasonton had his 3rd cavalry division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick, deployed near James City on the Union right flank. Meade ordered Brig. Gen. Henry Prince’s division of the III Corps to move up to reinforce Kilpatrick.

Meade then had Pleasonton deploy the rest of the cavalry to watch the Union army’s center and right. Early on October 9, Pleasonton ordered the 2nd division under Brig. Gen. David Gregg to march “night and day” to reach Culpeper Court House. Later he moved it farther to the northwest to watch the upper fords across the Rappahannock River. He ordered Kilpatrick to watch the roads leading to Culpeper Court House from Madison Court House. If the Confederate infantry appeared in force, he was to fight a retrograde action to slow its advance.

Kilpatrick deployed his troops to protect the signal station on Thoroughfare Mountain. He put Brig. Gen. Henry Davies’s brigade in front of James City to the northwest of the heights, and Brig. Gen. George Custer’s brigade behind Robertson River to the southwest.

Pleasonton gave the most dangerous assignment to the 1st division under Brig. Gen. John Buford. Pleasonton ordered Buford to cross the Rapidan River at Germanna Ford and march into the Wilderness. This would put his division on the Confederate right flank. Pleasonton ordered Buford to ride southwest along the Rapidan to join the I Corps at Morton’s Ford. If Lee’s army had not moved, Buford would have to ride six or seven miles across the front of it.

As Buford prepared to cross the river on the Union left, J.E.B. Stuart went into bivouac on the other flank with Hampton’s division. He established a strong picket line along Robertson River to ensure that a Union cavalry patrol would not discover the location of his force.

Stuart planned to attack across the river in the morning north of Thoroughfare Mountain. To draw attention from the main attack, he had some of his men demonstrate south of the mountain. During the night the Confederate skirmishers drove their Union counterparts back to their main line. Afraid he might have to make a sudden withdrawal, Custer ordered the whole brigade to mount at 3 am.

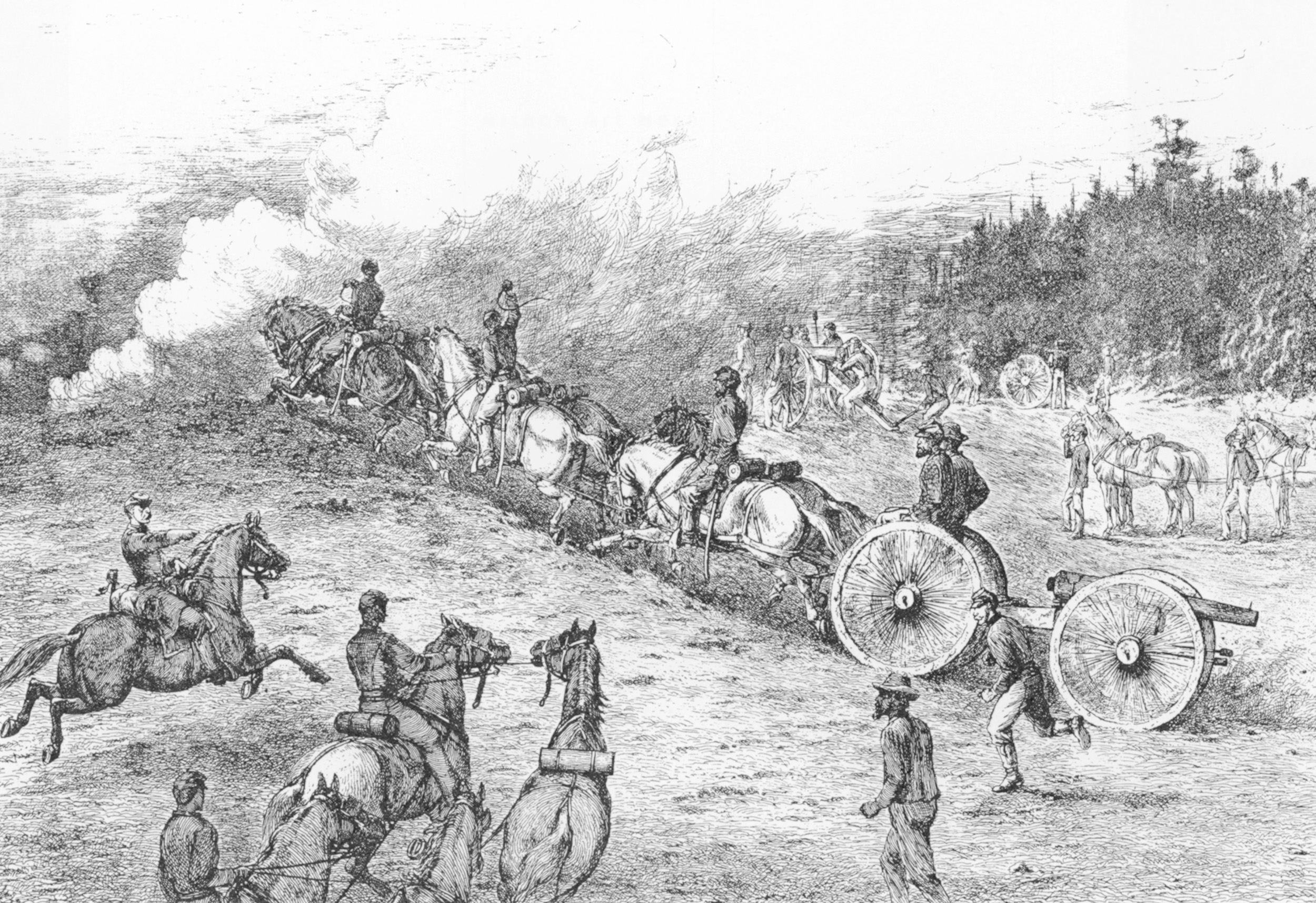

In the morning, Stuart attacked across Robertson River at Russell’s Ford with secondary attacks at Crigler’s Mill and Criglersville. The 4th North Carolina Cavalry splashed across the river first, driving the Union pickets back. Kilpatrick appealed to Prince to support him, but the infantry general refused at first to advance. By the time he started his troops forward, Stuart had seized the ground Kilpatrick wanted the infantry to defend.

With the Confederate cavalry driving him back, Kilpatrick abandoned Thoroughfare Mountain, evacuating the signal station as the Confederates sealed the far side of the heights. Davies’s brigade fell back behind Crooked Creek. About the same time, Custer retreated.

The rapid Confederate advance caught one Union infantry regiment alone in advance of the main force. On the afternoon of the 8th, Kilpatrick had asked Prince to move a regiment to a crossroads two miles beyond James City. He planned to send a cavalry regiment across Robertson River on the 9th, and wanted infantry close for support. Prince sent the 106th New York forward. When Prince learned the Confederates had crossed the river in force, he sent the 16th Massachusetts to support it. After it had marched a short distance, some of Davies’s troopers told the commander that Stuart’s cavalry had overrun the New York regiment.

It was true. When Stuart had seen the infantry, he decided to attack immediately. While Gordon’s brigade held the attention of the New York regiment, he took Young’s brigade around the right through some woods. A mounted charge by the 1st South Carolina Cavalry routed the infantry, but about half the Union troops succeeded in escaping into the woods.

About this time Kilpatrick and Prince clashed over who would command the Union forces at James City. Kilpatrick asked Prince to send him two regiments and a section of artillery. When Prince refused to give up part of his command, Kilpatrick offered to take command of all the troops. Prince countered with his own offer to take command. The two never resolved the problem of who was to be the superior, but Prince did send the cavalry leader the two regiments and guns he wanted.

By the time his troops reached James City, Stuart believed he had accomplished his mission by forcing Kilpatrick on the defensive. He was content to watch for the rest of the day, but to keep Kilpatrick and Prince from withdrawing, he sent his troopers down a road into town as he extended his line to the right. He put two guns in the woods at the edge of town with 150 dismounted cavalry from the 1st South Carolina Cavalry to support them. These demonstrations were so successful that Kilpatrick and Prince met to discuss where they should reform if Stuart forced them to retreat from the town.

When Custer arrived at James City around 3 pm, he saw the dismounted Confederate cavalry in the woods. He ordered a battalion of the 5th Michigan Cavalry to charge the two guns, but the dismounted Confederate cavalry, firing from behind a stonewall, drove it off.

The fighting between Stuart and Kilpatrick told Meade that the Confederates had already turned his right flank. At 5:30 he telegraphed Washington that the Confederates had driven back the cavalry and infantry on his right, and had seized Thoroughfare Mountain. From prisoners and deserters he concluded all of one Confederate infantry corps and part of a second were on his right between Madison Court House and Sperryville.

Meade correctly guessed that Lee intended to strike his right flank. To frustrate that plan, he decided to withdraw behind the Rappahannock River. Had he not done so, he would have remained within the narrowing triangle formed by the converging Rapidan and Rappahannock rivers. Lee would have liked to have found him there, with severe limits on his movements, but north of the Rappahannock Meade would have greater freedom to parry and thrust. Late in the afternoon, he ordered the army’s trains to cross the Rappahannock, and a short time later ordered the infantry to follow. In the evening he ordered Prince to withdraw from James City after dark.

As the infantry withdrew, Pleasonton remained at Culpeper Court House. While the infantry withdrew north, Buford’s division rode deeper in danger south of the Rapidan. At 8:30 on the morning of the 10th, the 1st Cavalry started southeast toward Germanna Ford. Colonel George Chapman’s brigade led the division south across the Rapidan River. At 1 pm, the 8th New York Cavalry forced its way across at Germanna Ford with the rest of the division close behind. Buford rode southwest paralleling the river.

As he approached Morton’s Ford, Buford discovered a small Confederate force blocking his path. Knowing the infantry of the I Corps was to cross the river to support him, he decided to wait until the next morning before advancing.

During the night, he discovered how serious his predicament was. Since the I Corps had withdrawn, he had no infantry support. (A courier arrived during the night with “new” orders he was not to cross the Rapidan River at all, but was to fall back behind the Rappahannock.) Buford decided the best way to reach safety was to force his way north across the Rapidan where he was.

Two miles away, upriver at Raccoon Ford, Fitz Lee learned of Buford’s presence on the south side of the Rapidan. Not content merely to drive the Union cavalry away, he wanted to destroy Buford’s command by trapping it between two wings of his division.

He committed his forces piecemeal to keep Buford in place while he set the trap. First, he sent some sharpshooters to harass the Union troops. At dawn. Brig. Gen. Lunsford Lomax’s brigade rode to Morton’s Ford, followed soon by Brig. Gen. John Chambliss’s brigade.

Colonel Thomas Owens’s brigade and Johnston’s infantry crossed the Rapidan River at Raccoon Ford to try to get ahead of Buford. Slowed to the speed of the infantry, this wing of the trap was still far from its objective when the Union cavalry began to cross the river.

Buford wanted to begin crossing at dawn but found the ford in such a state of disrepair that he had to detail Chapman’s men to improve it while Col. Thomas Devin’s brigade deployed on the heights to protect them. The Confederate cavalry continued to press Devin’s line without success until Chapman’s troopers were across.

Buford must have known of Lee’s plan because he immediately sent Chapman’s brigade to stop Owens. A short distance away, Chapman encountered Owens’s advance. The Union cavalry repulsed the first charge by the Confederate cavalry. As he prepared to repel another, Chapman saw Johnston’s Rebel infantry advancing in the distance. Chapman believed his command could not withstand a combined attack by infantry and cavalry. He ordered his troopers to retreat in the direction of Stevensburg as Devin’s brigade rode in the same direction.

Buford came upon a Union wagon train near Stevensburg going east to try to cross the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford. Near the town he united his two brigades and set up a line to protect the train as it rushed toward the safety of Mountain Run.

Owen’s brigade struck Buford’s line first. The 3rd Virginia Cavalry charged, but carbine fire from dismounted troopers shattered the attack. A charge by the 4th Virginia gave the 3rd the opportunity to retreat. A captain rallied the latter regiment in an open field while under fire.

Again, the approach of the Confederate infantry forced the Union cavalry to withdraw. Buford ordered his troopers to mount and fall back to Stevensburg where they made another stand. When he could no longer hold that position, he ordered the division to ride toward Brandy Station. Fitz Lee’s division kept after them in hot pursuit.

With the last of the infantry approaching the Rappahannock at 3 am on October 11, Pleasonton ordered Kilpatrick to fall back to Culpeper Court House, covering the rear of the withdrawing III and V Corps. Kilpatrick withdrew east from James City at 7 am on three different roads: Custer via Colvin’s Tavern, Davies via the James City road, and the 1st West Virginia and 5th New York on the Sperryville Pike. Kilpatrick found Pleasonton waiting for him at Culpeper Court House.

When Stuart discovered Kilpatrick gone from his front, he divided his command. He left Young’s brigade at James City to harass Kilpatrick’s rear guard. He took Gordon’s brigade north to Griffenburg where Funsten’s brigade waited. At the head of these two brigades, Stuart started down the Sperryville Pike toward Culpeper Court House.

As the Confederate cavalry approached Culpeper Court House from the north, it overtook the 106th New York Infantry. An aide to Stuart later wrote: “Never had I seen him [Stuart] more excited.” He sent a staff officer to find some cavalry before the Union infantry could escape. The officer returned with Company B of the 12th Virginia Cavalry under Lieutenant George Baylor. As the company emerged from the woods Stuart rode toward them, drawing his saber as he forced his mount over fallen trees and the debris of an abandoned camp. “Charge and cut them down!” he yelled to Baylor’s command.

As the Confederate cavalry advanced, the 106th New York deployed in a line to meet the charge. The infantry fired one volley before turning to flee. Baylor’s cavalry tried to follow them but a ditch spoiled the pursuit, allowing most of the Union troops to escape.

Stuart drove the two brigades down the road to try to take the retreating Union column in the flank. So anxious was he to catch up to Kilpatrick that Stuart rode with Baylor’s company out in front of both brigades.

When Stuart arrived at Culpeper Court House, he found the Union cavalry massed and ready to fight in an open field east of town. With only five regiments, he wisely chose not to attack.

But when he heard the sounds of Fitz Lee’s cannon to the south, Stuart saw an opportunity to trap Kilpatrick by maneuvering between the Union division and the Rappahannock River. The best way to do this was to seize the high ground of Fleetwood Hill at Brandy Station. The ground south and east of Brandy Station was essentially flat farmland with corn and wheat fields. Woods to the northeast hid the river from view in that direction; the dominant terrain feature was Fleetwood Hill, immediately north of Brandy Station. Stewart led his five regiments in a circuitous ride north and east in its direction to try to get around in front of the Union cavalry.

winter halted the fighting.

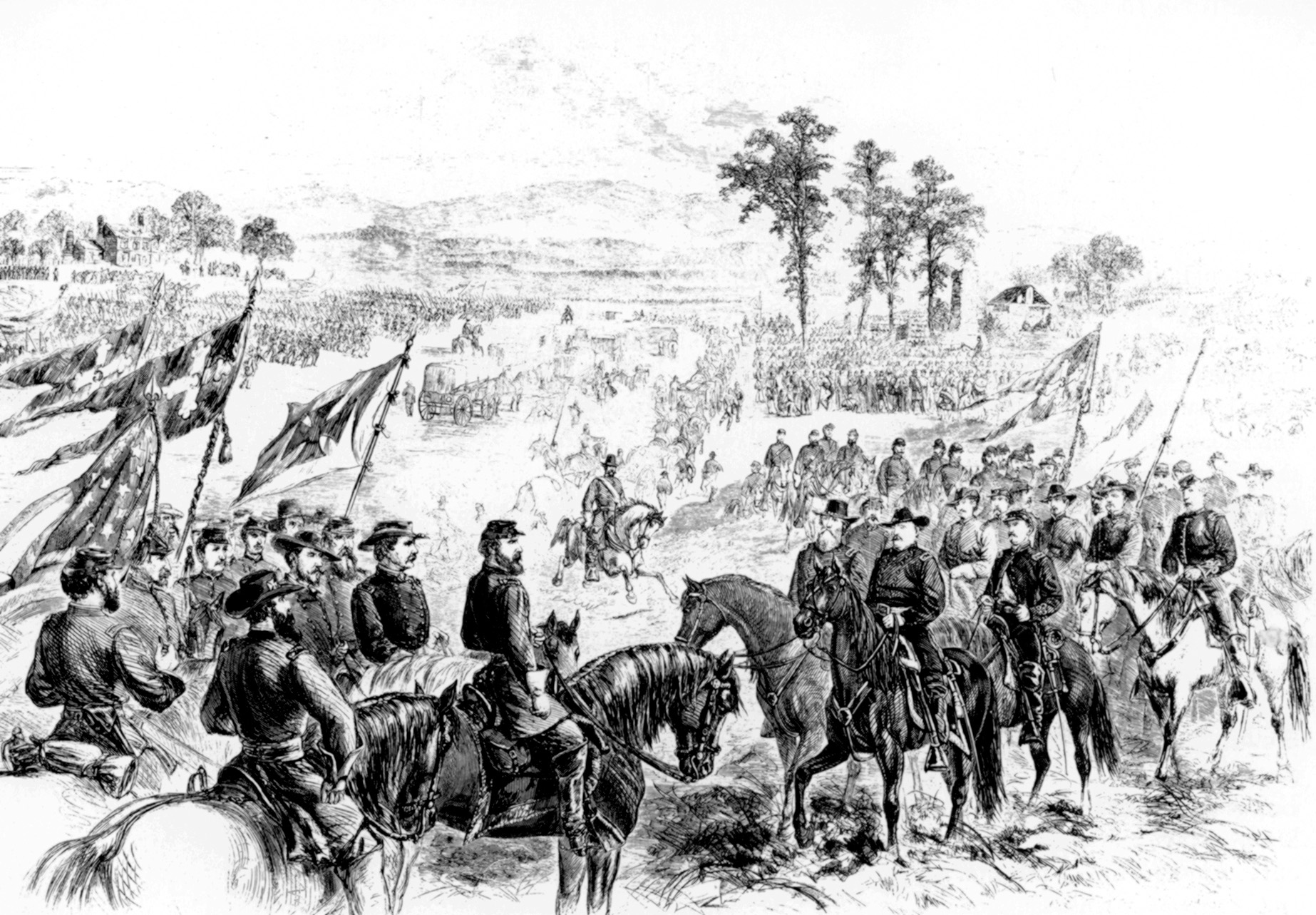

All four cavalry divisions arrived near Brandy Station about the same time, but the state of their arrival differed greatly. The Union divisions arrived more organized and closely aligned than did the Confederates ones. This allowed the Union generals the ability to deliver better organized attacks, and allowed them to react more quickly to Confederate counterattacks. The Southerners arrived in spread-out columns, forcing their commanders to commit their forces piecemeal to the battle.

Buford arrived first, crossing the railroad tracks to ride toward the Rappahannock. Near Fleetwood Hill, he ran into Union infantry. He wrote in his report: “To my surprise at Brandy I found the rear guard of the Fifth Corps passing through to cross the Rappahannock. I knew nothing up to this time of how extensive this retrograde movement of our army was, and here learned that General Pleasonton with the Third Division was still in rear of the Fifth Corps. Arrangements immediately made to make a stand until the Third Division should arrive.”

Buford knew Fleetwood Hill dominated the terrain. He had spent most of June 9—in the biggest cavalry clash of the war, the Battle of Brandy Station—trying to gain control of it from Stuart’s cavalry. Once he knew he had to make a stand there, he directed his division to seize Fleetwood Hill.

Lomax’s brigade arrived next, still pursuing Buford. He seized the railroad at Brandy Station but withdrew when he saw Kilpatrick’s advance coming down the tracks toward him. He dismounted some men and placed them in the woods near the station to face Buford. He deployed the remainder of his brigade to face Kilpatrick.

When Stuart reached the open plain near Brandy Station, he saw Kilpatrick’s division advancing down the railroad at a trot on a line of march parallel to his own. He committed his units piecemeal as they arrived. The 1st North Carolina and the 12th Virginia attacked first, followed by the 4th and 5th North Carolina. As they rode along a narrow lane in columns of fours, the 18th Pennsylvania attacked them on the flank and routed them. When the 7th Virginia came up, Stuart threw it on the flank of the 18th Pennsylvania, routing it in turn. By the time Stuart organized another charge, the 18th Pennsylvania had retreated to the main body of the division.

As Custer and his brigade approached Brandy Station, a courier informed the flamboyant general that a large Confederate force, thought to be a brigade, blocked his route to the river. Custer rode forward to take a look for himself. When Pleasonton arrived, Custer suggested a frontal attack to which the general agreed.

Lieutenant Frederick Whittaker, Custer’s aide and future biographer, recalled the scene. After ordering his troopers to draw sabers, Custer rode to the head of the 5th Michigan, snatched off his hat, and raised himself in his stirrups: “Boys of Michigan, there are some people between us and home. I’m going home, who else goes?”

Custer’s report of the same scene was only slightly less romanticized: “After ordering them to draw their sabers,” the 24-year-old brevetted general wrote, “I informed them that they were surrounded, and all we had to do was to open a way with our sabers. They showed their determination and purpose by giving three hearty cheers. At this moment the band struck up the inspiring air of Yankee Doodle, which excited the enthusiasm of the entire command to the highest pitch and made each individual member feel as if he was a host to himself. Simultaneously both regiments moved forward to the attack. It required but a glance at the countenances of the men to enable me to read the settled determination with which they undertook the task before them.”

During the Civil War, the Union cavalry was organized so part of each regiment was designed to fight on horseback while the remainder dismounted to fight with their carbines. Custer had the 1st and 5th Michigan designated as saber regiments. He used them to charge the Confederate lines while the 6th and 7th Michigan protected the rear.

Custer hammered the Confederate lines with one charge after another. Lomax soon needed help, but when Fitz Lee heard the gunfire, he slowed, thinking reinforcements had reached Buford. When he finally came into range, his cannon fired at Stuart by mistake, thinking those troops were Union cavalry.

As the first Union charge began, Custer’s old friend, Col. Thomas Rosser, pulled the 5th Virginia out of the way to keep Custer from trapping it. When the Union cavalry passed, he attacked its flank. Rosser wrote after the war: “Never in my life did I reap such a rich harvest in horses and prisoners.”

Owens discovered Union cavalry on three sides of his brigade. Not realizing Stuart was near, he retreated out of the battle. Lomax found his dismounted troopers surrounded several times, forcing him to charge to rescue them.

Once through the Confederate lines, Kilpatrick’s division joined Buford at Fleetwood Hill. The battle became a series of charges and countercharges. Lomax reported he made a total of five. Colonel Edward Sawyer of the 1st Vermont wrote: “Charges and countercharges were frequent in every direction, and as far as the eye could see over the vast rolling field were encounters by regiments, by battalions, by squads, and individuals, in hand-to-hand combat.” Davies reported that: “A description of the engagement is hardly practical, as it consisted of a series of gallant charges made wherever the enemy appeared .…”

Across the Rappahannock, Maj. Gen. George Sykes saw the cavalry battle taking place. While most of the V Corps had crossed, his rear guard was still west of the river. When a courier arrived at Fleetwood Hill asking Kilpatrick if he wanted Sykes to send his infantry to help, the cavalry leader reportedly sent word for Sykes to keep his infantry out of the way of this cavalry.

A livid Sykes was seen walking about his headquarters so angry that he was stomping his foot.

Beyond the Rappahannock, the V Corps artillery deployed to cover the withdrawal of the rear guard of the corps. Once the infantry was all across, the Union cavalry fell back. Fire from the Union cannon was so heavy that it forced the Confederate cavalry to take cover behind Fleetwood Hill. After dark, Pleasonton brought both divisions across the river.

Lee’s plan to attack Meade’s right flank within the “vee” of the two rivers had failed. The Army of the Potomac had fallen back behind the Rappahannock River. An attack on this new position would require a frontal attack, something Lee did not want to do.

But rather than retire behind the Rapidan again, Lee decided to try once more. His two infantry corps would swing to the left again, hopefully coming together to attack the Union right somewhere in the vicinity of Catlett’s Station, or perhaps Bristoe Station to the northeast.

Lee’s orders to Stuart for this maneuver were similar to those of the first. Stuart put his weary regiments in motion again, and headed north toward David Gregg’s cavalry division watching the upper fords of the Rappahannock.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments