By Kevin Seabrooke

In the early hours of May 15, 1918, U.S. Army Corporal Henry Johnson and Private Needham Roberts sat in an outpost along the French lines at the western edge of the Argonne Forest. German snipers had fired at them when they’d first come on sentry duty for the midnight-to-four a.m. shift, prompting the men to line up a box of grenades in case of an attack.

But all had remained quiet until about 2 a.m., when the stillness of the night was broken by the distinctive “snick” of wire cutters.

Johnson threw a grenade toward the perimeter fence and ordered Roberts to run back to camp to inform the French troops of the attack—the pair were part of the all-black 369th Infantry Regiment, now attached to the French Fourth Army. Having received little training, the unit had no combat experience and had previously been performing menial tasks since its arrival overseas.

Roberts started to run, but came back to help Johnson when the Germans opened fire and hurled grenades at the outpost. Shrapnel from one of those grenades hit Roberts, wounding him badly. Johnson helped him back to safety, where Roberts was able to lie in the trench handing grenades to Johnson.

But there were too many Germans, advancing from every direction. Eventually, Johnson ran out of grenades, then bullets, before they were on top of him.

Johnson swung his rifle like a club until the stock broke. Overwhelmed, he was sent sprawling by a blow to the head. He watched as the Germans started to drag Roberts away and reached for the only weapon he had left—his bolo knife.

Scrambling to his feet, he charged, hacking away at the Germans before they could get a clean shot at him. Johnson was shot in the arm as he stabbed several Germans, including one who had climbed on his back. As Johnson dragged Roberts back, the Germans retreated as the sounds of the Allied forces approaching grew louder.

The morning light revealed Johnson had saved Roberts and killed four Germans, wounding possibly 10-20 more. Despite suffering 21 wounds, he had single-handedly kept the Germans from breaking the French line.

“Each slash meant something, believe me. I wasn’t doing exercises, let me tell you,” Johnson would later recall.

Born on July 15, 1892, in Winston Salem, North Carolina, William Henry Johnson moved to New York as a teenager. He worked various jobs, including a chauffeur, soda mixer, laborer in a coal yard, and a redcap porter at Albany’s Union Station. On June 5, 1917, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and was assigned to Company C, 15th New York (Colored) Infantry Regiment, a National Guard unit made up of enlisted black soldiers with both black and white officers, that had been formed in 1916.

Federalized in 1917 and shipped to France in December, the unit was designated as 369th Infantry Regiment, part of the segregated 93rd Infantry Division.

The 93rd was largely assigned to non-combat roles as stevedores and laborers—unloading supplies and digging latrines. As was often the case back home in the U.S., the white soldiers had little regard for the African-American troops, and refused to serve in trenches with them.

Major General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), reportedly wanted to keep American units together, though segregated, but some units from the 93rd were detached to serve with the French, whose ranks included Black soldiers from its empire.

The 369th Infantry was attached to the French 161st Division on April 8, 1918. They were given French helmets, rifles, and taught just enough of the language to understand orders.

Johnson and the 369th deployed to the front near the Argonne Forest, alongside white French soldiers who mostly treated them better than their American counterparts.

While some black leaders had questioned why African Americans should sacrifice themselves for a nation that would not grant them full citizenship, others, such as W.E.B. DuBois said that “while the war lasts [we should] forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our white fellow citizens and allied nations that are fighting for democracy.”

Some 380,000 African Americans would answer that call and serve in the Army during World War I. Of these men, 200,000 were sent overseas—mostly in support roles—but about 42,000 saw combat.

Among themselves, the soldiers of the 369th were the “Black Rattlers,” complete with a coiled rattlesnake poised to strike on their unit crest. The French soldiers they fought with called them “Men of Bronze” (Hommes de Bronze). By the time they paraded through the streets of New York in 1919, they were famous by the name that appeared in The New York Times headline: “Harlem Hellfighters.”

It was the Germans they fought against who gave the 369th the name “Hollenkampfer.” A captured Prussian officer reportedly said that the Hellfighters were “devils” that “smile while they kill and won’t be taken alive.” The U.S. Army officially recognized the name for the unit in 2020.

The French 16th Division, which commanded the Hellfighters, quickly recognized the actions of Johnson and Roberts. The two soldiers received the Croix du Guerre, France’s highest military honor.

The French orders, dated May 16, state Henry Johnson “gave a magnificent example of courage and energy.” They were the first U.S. soldiers to earn this distinction, and Johnson’s medal included the coveted Gold Palm for extraordinary valor.

“There wasn’t anything so fine about it,” he said later. “Just fought for my life. A rabbit would have done that.”

From that point on, Johnson was known as “Black Death.” The 369th would go on to prove itself in combat operations through the rest of the war—spending 191 days on the front lines— and was decorated with the French Croix de Guerre with Silver Star for service during the Meuse-Argonne campaign and cited for bravery 11 times for the unit’s actions. Its members also received 171 individual decorations for heroism.

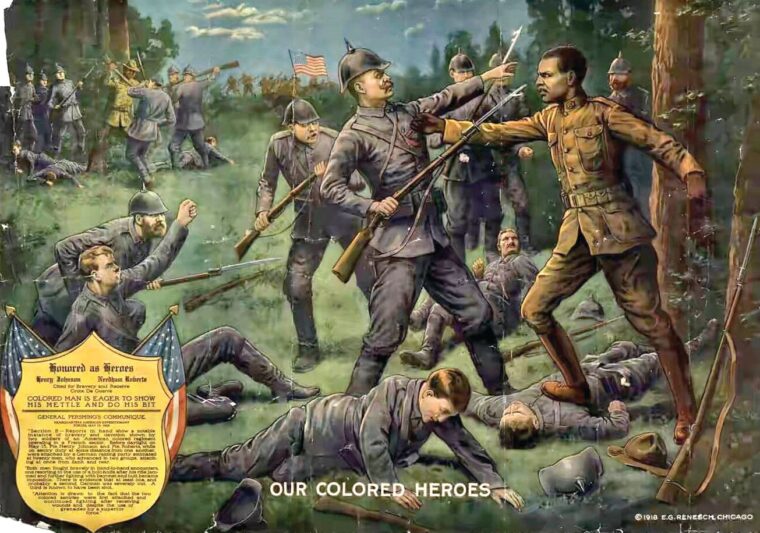

Johnson would be singled out for his heroism and actions under fire. Former President Theodore Roosevelt called Johnson one of the five bravest Americans to serve in World War I. Johnson’s image was used by the Army to recruit new soldiers and to sell Victory War Stamps—“Henry Johnson licked a dozen Germans. How many stamps have you licked?”

After the war, Johnson and Roberts returned home as national heroes. Promoted to sergeant, Johnson led the New York City parade for the 369th in February 1919. The unit had been denied the honor of marching in a parade of “The Rainbow Division” before being shipped out to Europe. National Guard units from across the country had been combined into one unit to be deployed to France together so that no particular state or region felt slighted.

The commander of the unit that would become the 369th, Col. William Hayward, was told that “black is not a color in the rainbow.”

Johnson’s fame was fleeting. The 369th had spent more than six months in combat, possibly more than any U.S. unit in the war. They suffered some 1,500 casualties with only 900 replacements. The lack of replacements and constant stress of the front line left them exhausted by the end of the war in November. And the America they came back to was still the America they had left—Jim Crow, second-class citizenship and the systematic denial of equal rights to black Americans.

Johnson was taking part in a series of paid lectures until one evening in St. Louis he went off the “racial harmony in the trenches”script and said what was really on his mind—that white soldiers refused to share trenches with Blacks and other abuses.

Johnson was “shunted aside” after that, according to the National Guard, and offered no more speaking engagements. A warrant for Johnson’s arrest was reportedly issued for wearing his uniform beyond the prescribed date of his commission.

Though he was praised publicly by the press and the Army, Johnson’s discharge papers didn’t mention his debilitating injuries, so he received no disability allowance.

That he didn’t receive a Purple Heart at the time was not out of the ordinary. The Badge of Military Merit, which became the Purple Heart, had been established by President George Washington in 1782. It was only given to three soldiers from the Revolutionary War, and though it was never discontinued, it was not proposed officially until after World War I.

In 1932, the War Department authorized the awarding of the Purple Heart to all soldiers, upon their request, who had been awarded the Meritorious Service Citation Certificate, Army Wound Ribbon, or were authorized to wear Wound Chevrons subsequent to April 5, 1917, the day before the U.S. entered World War I.

The first Purple Heart was awarded to General Douglas MacArthur in February, 1932.

With no other way to make money, Johnson returned to his job as a porter at the train station in Albany, New York. Hampered by his lack of education and unable to hold a steady job due to his injuries—his shattered left foot had been put back together with a metal plate—Johnson struggled. Unable to support himself and his family, his marriage broke up and he died alone and penniless at age 32 on July 1, 1929, in New Lenox, Illinois. The cause was myocarditis, following a tuberculosis diagnosis.

A re-examination of the World War I military records of African Americans in the 1990s uncovered Johnson’s story. In 1996, President Bill Clinton posthumously awarded Johnson the Purple Heart.

For many years, it had been assumed that Johnson had been buried in a pauper’s grave. But in 2001, historians from the New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs discovered that a “William Henry Johnson”—he had only given the name Henry Johnson when he enlisted—had been buried in Arlington National Cemetery (Section 25, Site 64).

After this discovery, the Army awarded Johnson the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second-highest military decoration.

To the dismay of many supporters, Johnson had not yet been awarded the Medal of Honor, for courageous military action, due to a lack of military documentation.

Efforts to recognize Johnson’s valor continued until researchers found the needed documentation, including a memo written by Army Commander in Chief Gen. John J. Pershing. It confirmed that Johnson had been an American soldier in spite of the fact that he had worn a French uniform and served under French command.

Pershing wrote that Johnson’s unit “first attacked continued fighting after receiving wounds, and despite of use of grenades by superior force, and should be given credit for preventing by their bravery the taking prisoner of our men.”

At a Whitehouse ceremony on June 2, 2015, Johnson was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by President Barack Obama.

At the ceremony, Obama said, “The least we can do is to say, ‘We know who you are, we know what you did for us. We are forever grateful.’”

His Medal of Honor citation reads, in part: “Private Johnson’s extraordinary heroism and selflessness above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, Company C, 369th Infantry Regiment, 93d Infantry Division and the United States Army.”

In June 2023, the U.S. Army renamed Fort Polk in Leesville, Louisiana, as Fort Johnson. The base, officially named Joint Readiness Training Center and Fort Johnson, replaced the name of Confederate commander Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk.

Sergeant Johnson was done dirty, pure and simple. He earned and deserved much better. Sergeant Johnson’s in a better place now, where his service and sacrifice have been amply and eternally rewarded.

Recommend checking the date at the start of the story. In May 1917 we’d been at war maybe a month.

Good catch on the year. It’s been corrected.

I am glad this hero finally got the recognition he deserves.