By William Welsh

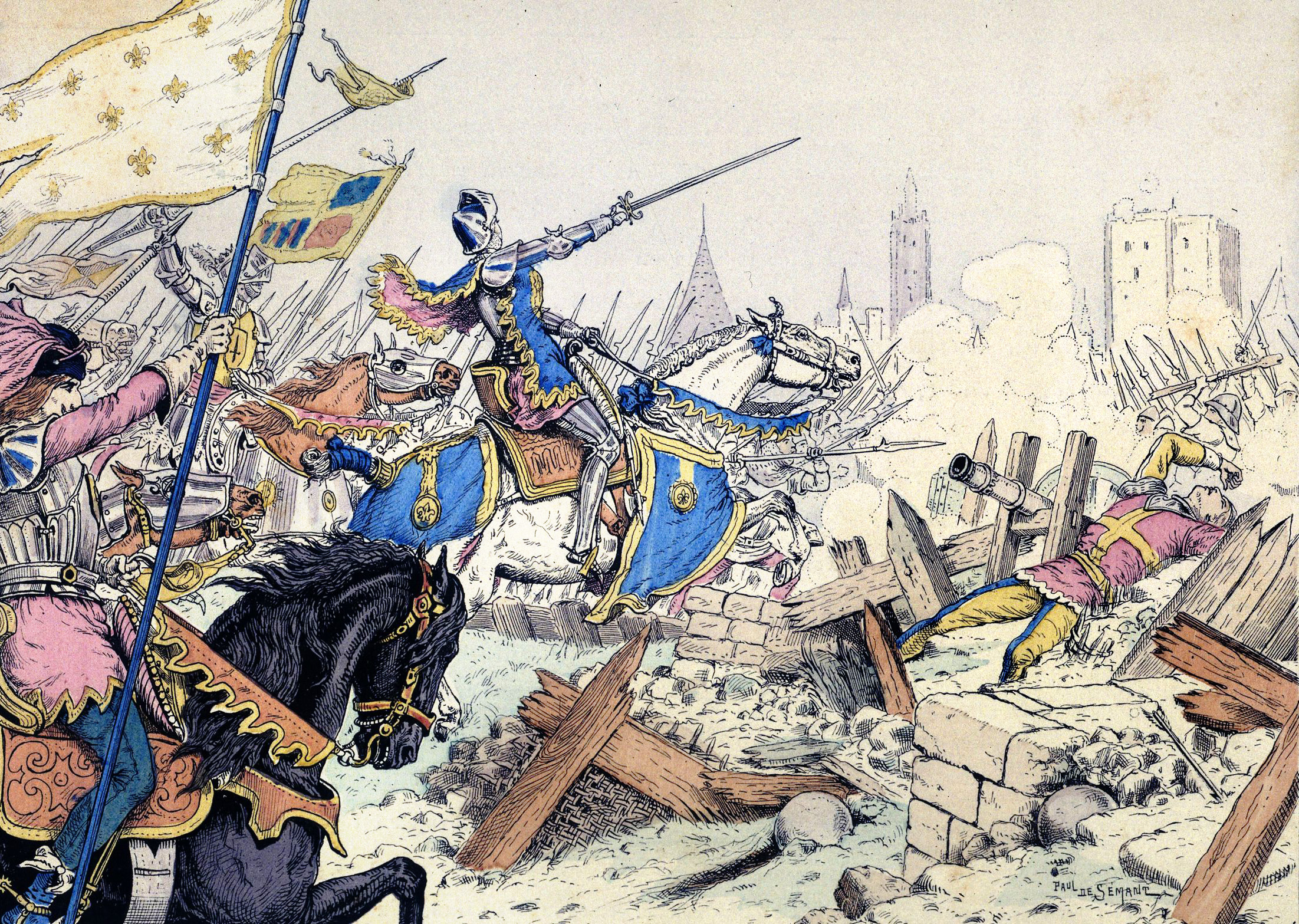

None of those present at the war council held on July 18, 1429, at Beaugency in central France seemed to object to the peculiar sight of an armor-clad young woman advising some of the greatest military captains of the age on how to proceed with the campaign to crown the Dauphin Charles king of France. Prone to dithering, the French commanders owed much of their current success to the persistence and impatience of the Maid of Domremy, who considered it her mission to raise the siege of Orleans and clear English resistance from the Loire Valley, making possible the coronation of the Dauphin at Reims.

Joan of Arc had already proved that she could work miracles. With her guidance, the French had expelled their despised foes from Orleans on May 8, and in a whirlwind offensive lasting only a week they had driven the English from their last three garrisons on the upper Loire River. The English and their Burgundian allies still controlled all of the territories north of the Loire River, including the Ile de France on which Paris was situated and the wealthy territory of Aquitaine in southwestern France.

While the French captains pondered their next move, 51-year-old Sir John Fastolf led a downtrodden army of 5,000 English and Burgundian forces toward the safety of friendly territory in northern France. From Joan’s standpoint, leaving such an army intact would delay or prevent the Dauphin’s coronation that she saw as the culmination of her God-given quest. “In the name of God, let us go fight them!” she shouted at the council. “If they were hung up in clouds, we would get them, for God sent us that we should punish them!” Speed was of the essence; it was essential that the French overtake the enemy on their northward march. To drive the point home, Joan chose more secular words. “You have spurs,” she exclaimed. “Use them.”

Joan’s Visions From God

After nearly a century of off-and-on strife between the kings of England and France, the French people had suffered so many disheartening defeats and so much strife that they welcomed a self-professed savior such as Joan—as long as she helped them achieve victories over the hated English. In a deeply religious period of Western civilization, it was easy for the French to believe that the maid was on a divine mission.

Joan was born on January, 6, 1412, in Domremy, a small village in the rolling countryside of Lorraine in northeastern France. At the time of her birth, France was embroiled in a civil war pitting the Duke of Orleans and his kinsmen against the Duke of Burgundy for control of the government in Paris. Both factions, the Armagnacs and the Burgundians, sought to make peace with the English to guarantee the supremacy of their faction in France. After an unsuccessful attempt to capture Paris the year before Joan was born, the Armagnacs retreated south of the Loire, a wide river that served as a natural barrier between northern and southern France.

Beginning on her 13th birthday in 1425, Joan began to hear voices of various saints and angels instructing her to go immediately to the aid of the king of France. By that time, the crown of France was claimed by the infant Henry VI, king of England, and by the Dauphin Charles, fifth and youngest son of French King Charles VI. At the age of 17, Joan persuaded Robert de Baudricourt, a local Armagnac commander, to take her to see the Dauphin so that she might assist him in lifting the English siege of Orleans, which the heavenly voices had told her was the first step toward the Dauphin’s coronation. On March 6, Joan was received at court at Chinon, where she was subjected to lengthy interviews and tests to determine whether she was worthy of serving in the Dauphin’s army.

By mid-March, she was cleared to participate in the campaign. On March 22, she dictated her first written ultimatum to the English, demanding that they leave France or prepare for a new campaign against the French. When word of her strong language and courageous spirit spread throughout the Armagnac regions of France, hundreds of fresh recruits rushed to join the army and fight the English at Orleans.

6,000 Soldiers at Orleans

Joan arrived at Orleans on April 29 with an escort of 200 hand-picked men-at-arms eager to begin the battle she believed would break the English siege. Close behind was the 4,000-man relief army commanded by 22-year-old John II, Duke of Alençon. Joan immediately demanded that the commander of the Orleans garrison, John, Count of Dunois and Longueville, also known as the Bastard of Orleans, switch over to the offensive against the English. Foreseeing that Joan and the Bastard were likely to clash because of their similarly assertive temperaments, the Dauphin gave Alençon overall command of the forces at Orleans so that he could mediate between the two hotheads. Alençon was perfectly positioned for the role; he was a close friend of Joan and a brother-in-law to the Bastard.

Together, the garrison and the relief army numbered 8,000 men, which was nearly double what the English had deployed in key locations outside the city. During a desperate fight to retake the Tourelles gate on the far end of the Loire bridge leading into Orleans, Joan was struck in the shoulder by an arrow. Miraculously, she survived the serious wound. On May 8, the English quit their siege, which had lasted 210 days.

Before departing Orleans, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, commander of the English forces, deployed his men in battle formation outside the walls as a final challenge to the French. Although the French formed up opposite the English, they decided not to attack. Realizing that the French were willing to allow his army to withdraw intact, Suffolk unwisely divided his army into smaller units in an attempt to hold three remaining English strongholds—Jargeau, Meung, and Beaugency—and isolate the French in Orleans. Suffolk intended to wait for reinforcements from English-held territories in northern France. John, Duke of Bedford, Henry VI’s regent in France, began casting about for reinforcements to assist Suffolk.

Suffolk marched east with 700 men to the town of Jargeau, which was situated about nine miles from Orleans on the south bank of the Loire. He ordered Sir John Talbot and Sir Thomas Scales to take an equal number of men and march west to the towns of Meung and Beaugency, respectively. The three cities were strategically important because each had a fortified bridge that spanned the Loire.

Because the English garrisons on the Loire were in excellent defensive positions in walled towns and castles, it was necessary to add new recruits to the French army. For this reason, Joan, Alençon, and the Bastard visited the Dauphin at his new base at Tours to plead for reinforcements. The Dauphin responded favorably to Joan’s request to call up additional forces to rid the Loire Valley of the English invaders. In a month’s time, the French army at Orleans tripled in size to 6,000 troops.

Rejecting Negotiations

On June 10, Alençon’s army, which included Joan, marched east to Jargeau to reconnoiter the English position. The following day, the French captains held another war council. Of critical concern was the specter of an English relief army led by Fastolf hovering on the north bank. Fastoff, the French believed, had been sent to reinforce the beleaguered English garrisons on the Loire. Jargeau was well fortified to withstand an attack. The city was situated on the south bank with a wall and a ditch that enclosed most of its buildings and homes. The city had five towers, three fortified gates, and a fortified bridge leading to the north bank.

The French were still discussing how best to deploy their forces to capture Jargeau when the English troops inside the city took matters into their own hands. A portion of the garrison sallied forth in an effort to disrupt the French preparations. The French troops, caught by surprise, fell back before their captains rallied them. The fighting seesawed back and forth in the Jargeau suburbs. By the end of the day, the French had driven the English back inside the town and were in firm control of the surrounding countryside. Joan approached the walls that evening and yelled for the English to surrender or suffer the consequences. “Surrender this place to the King of Heaven, and to gentle King Charles, and you can go,” she said. “Otherwise you will be massacred.” She was answered with silence.

On June 12, the French hauled their siege guns into position and began to batter Jargeau’s walls. One group of guns went into action in the suburbs, hammering the walls at close range, while a battery equipped with long-range guns known as bombards opened up from the opposite bank. The most formidable and effective of the siege weapons employed by the French was a large mortar that the gunners used to target the towers, one of which was toppled after three shots.

Suffolk quickly realized that the English could only hold out for a matter of hours against such weapons. He sent word to French captain Etienne de Vignolles, nicknamed La Hire (Anger), that he wished to negotiate terms of surrender. Suffolk’s request was deemed a breach of protocol by the French since it was directed at one of the subordinate commanders and not at Alençon, the head of the army. Although Joan was willing to negotiate with the English, Alençon was infuriated by the English attempt to bypass his authority and flatly refused any discussion of surrender terms.

Joan of Arc Attacks

This left nothing to do but resume the attack. During another meeting of the French captains, Joan suggested an all-out attack. The majority agreed, and as she had done at Orleans, Joan put herself in danger’s path by personally leading a column of attackers against the most formidable position. The men in Joan’s column dodged arrows, missiles, and shells fired from the high walls and towers as they advanced with scaling ladders toward the ditch at the base of the wall.

One particularly ferocious English defender singlehandedly hurled large stones and cannon balls down on the attackers and kicked over ladders as French men-at-arms desperately sought to climb onto the parapets. To slay the determined adversary, the artillery commanders called on one of their master gunners, who killed him with a well-aimed shot from a hand culverin. Joan was scaling a ladder when she was struck on the helmet by a stone hurled by a defender on top of the wall. She was dazed but not seriously wounded and led another sortie against the walls once she had recovered.

After repeated attacks against the walls, the French fought their way onto the parapets and into the town. Because the English resisted, they were shown no quarter. All were slain except the few of high station who might be ransomed. Suffolk and his brother John were taken prisoner, but Suffolk’s other brother, Andrew, was killed in the fighting. When Suffolk learned that he had been captured by a squire, he knighted the individual on the spot so that he could say he had surrendered to a knight.

The Strongholds of Meung and Beaugency

While the French rested at Orleans after the capture of Jargeau, Fastolf arrived at Janville following a four-day march from Paris. The town, which was situated 12 miles north of Orleans, lay within a day’s march of the two remaining English strongholds. Both Meung and Beaugency were situated on the north bank of the Loire and had fortified bridges leading across to the south. To further strengthen the bridge at Meung, the English had established a small, fortified bridgehead to resist the expected French attack.

With far less debate than had preceded the attack against Jargeau, French captains resolved to capture the Meung bridge and launch a major assault against the town. The latter would pose a formidable challenge because Talbot and Scales had deployed their main force in a strong position on the north bank at Meung within a large castle just outside the town walls. The French army vastly outnumbered the English garrison manning the bridgehead. In a quick fight on June 15, the French overran the position with negligible losses. Joan was wounded in the leg during the fighting and lay in a ditch in front of the English barricades until French soldiers found her at nightfall and carried her safely away.

Rather than assault the Meung castle, which was unlikely to fall to an initial assault and would require a siege that might drag on for weeks, Alençon decided to leave a small portion of his army behind at the Meung bridge while the main body of troops bypassed the castle and marched to Beaugency. The French reasoned that this would give Talbot and Scales an opportunity to withdraw north to avoid being trapped. Instead, Talbot and Scales chose to remain in the castle.

Constable Richemont’s Defection

While at Meung, Alençon’s army had unexpectedly been reinforced by a smaller French army led by Constable of France Arthur de Richemont. Richemont was the third son of John IV, Duke of Brittany. The dukes of Brittany had strong familial ties to England, France, and Burgundy, and their loyalties were divided throughout the conflict. Richemont had supported the Anglo-Burgundian alliance as a young man, hoping to gain a position of distinction for his loyalty, but when Bedford refused him a command in 1424, he promptly switched sides. To reward him for abandoning the English, Charles made him a constable.

By the time the offensive got under way in the Loire Valley, Richemont had fallen out of favor with the Dauphin. The two argued heatedly over war strategy before Joan arrived on the scene. Richemont favored an aggressive campaign against the English, much like that which Joan was waging, while the Dauphin favored a defensive war. The dispute between the Dauphin and the constable continued to simmer, and Charles sent explicit instructions to Alençon not to join forces with the constable.

Richemont arrived with 1,200 men outside Meung on June 15 and asked Alençon to join forces for the attack on the remaining fortress at Beaugency. Although Alençon was adamant that Richemont not be allowed to join the campaign, Joan was willing to allow the constable to join the army on the grounds that his forces likely would be needed in future operations against the English. The other French captains concurred. To appease Alençon, Joan had Richemont guarantee in writing that he was loyal to the Dauphin.

Countermarching on Meung

On the same day that Richemont joined Alençon’s army, Talbot rode north with an escort to Janville, where he met with Fastolf to discuss the English army’s next move. Fastolf recommended that since the French had the upper hand it would be wise to withdraw the remaining garrisons at Meung and Beaugency and regroup farther north. Talbot, who had invested great effort in securing and retaining the garrisons, was unwilling to give them up without a fight. After a heated discussion, Fastolf agreed to advance to the Loire and assist the hard-pressed garrisons.

On June 16, the French launched an attack on the fortified bridge at Beaugency from the north bank. Beaugency was surrounded by a strong, five-story castle keep in which the majority of the English were quartered. The English garrison was commanded by the knights Richard Guestin and Matthew Gough, who deployed the main body of their force within the castle keep and dispatched a small contingent of men-at-arms and archers to guard the bridge. After a brief fight, French dismounted men-at-arms captured the bridge, and gunners begin shelling the town and castle with a battery of bombards positioned on the south bank. Realizing the strength of the castle keep, French commanders were reluctant to launch a direct assault on the position. They hoped that the heavy bombardment would compel the English to surrender.

When Fastolf arrived at Meung on June 17, he reconnoitered the French position at the bridge. It was apparent that the French were reinforcing the north end of the bridge in anticipation of an English attempt to retake it. Fastolf decided to lead his forces west along the north bank to Beaugency. Joined by Talbot and Scales, Fastolf continued toward Beaugency. Two miles outside of the town, the English found their way blocked by the French army drawn up in battle formation on a hill.

Leaving behind Richemont’s infantry and the siege guns to keep the enemy garrison inside Beaugency from counterattacking, Alençon, Joan, and her captains selected the most advantageous terrain they could find to establish a strong defensive position to await an English attack. Realizing that they were outnumbered and in a poor tactical position to press an attack, Fastolf and the English commanders decided to countermarch to Meung, where they would consider their next move.

Fastolf’s army camped at Meung the night of June 17. The following morning, the English formed for battle and made one more attempt to dislodge the French from the Meung bridge. After the English attack was repulsed, Talbot agreed to abandon Meung. About the same time, unknown to Fastolf and Talbot, the English commanders at Beaugency had signed a surrender agreement with Alençon that gave them generous terms for relinquishing the town. The Beaugency garrison was allowed to withdraw with its arms and baggage to Normandy, provided they agreed not to engage the French for 10 days. This would allow Alençon’s army enough time to defeat Fastolf on its own.

In Pursuit of the English Army

By late morning on July 18, Fastolf’s army began its long retreat northward to Paris. Although English morale was low as a result of the loss of Jargeau and the repulses at the Loire strongholds west of Orleans, they retreated across the fields in good order, with no evidence of haste or panic. Their first objective was to reach the relative safety of Janville. Slowly, the English made their retreat.

The slow pace was the result of Fastolf’s effort to protect his baggage train and artillery by placing the slowest moving elements at the front of the column. Fastolf’s vanguard comprised a small group of mounted men-at-arms trailed by baggage carts, limbered artillery, and camp followers. Behind the vanguard, Fastolf, Talbot, and Scales led a group of inexperienced French levies drawn from Normandy and Isle de France. The rearguard, however, contained highly disciplined English men-at-arms and wily, experienced archers.

The French military had suffered so many defeats during the Hundred Years’ War that aggressive offensive action was simply not in the blood of its leaders. Throughout the Loire campaign, Joan had prodded her commanders to take action whenever they dithered over their next step. Joan believed that if Fastolf’s army was allowed to retreat intact it might block the eventual march of French forces to Reims for the Dauphin’s coronation. Joan urged the final destruction of Fastolf’s army.

As soon as it was apparent that Fastolf’s army had abandoned Meung, a French vanguard composed of 1,500 mounted men-at-arms led by La Hire and other captains took up the pursuit. The main French body followed, led by Alençon and accompanied by Joan, Richemont and others, but was unable to keep pace with the hard-riding vanguard. La Hire was careful to keep his force together in case the English prepared an ambush. The main body of the French army reached the village of St. Sigismond at noon, and Alençon issued orders for a brief rest to allow his troops to have a midday meal. In contrast, La Hire kept his mounted force in the saddle, which allowed him to close to within a couple miles of the English rear guard.

The English Take Their Positions

The blistering summer heat did nothing to improve the slow pace of the English army as it tramped north toward Janville. At the same time that the French reached St. Sigismond, the English arrived at the intersection of the Blois-Paris and Orleans-Chartres roads, located two miles southeast of the village of Patay. When he arrived at the intersection, Fastolf learned that a group of French heavy cavalry was within striking distance of the English rear. He held a quick council of war with Talbot and Scales to discuss their options. They determined that since they could not outrun the French they would deploy their forces and hope they could repulse Alençon’s army.

Unfortunately for the English, the mainly flat terrain surrounding the crossroads offered little defensive advantage. Worse yet, the landscape was comprised of largely open fields with only a few clumps of forest dotting the area. Fastolf ordered his artillery and baggage onto a slight rise known locally as La Garenne, which was situated west of the Blois-Paris road behind meandering Laconie Creek. Next, he instructed Talbot to take 500 archers armed with their deadly longbows and deploy them in a dip in the landscape where several patches of woods and roadside hedges would afford enough cover to hide the archers from the French cavalry. Once the archers had inflicted substantial losses on the French cavalry, they were to withdraw from their advanced position and rejoin the main battle line.

Talbot’s archers were deployed by 1:30 pm in two groups on opposite sides of the Blois-Paris road just south of the crossroads. The hasty deployment did not allow sufficient time for the English longbowmen to pound into the ground the stakes they carried with them to ward off cavalry charges. Although they had the advantage of surprise, they lacked this basic defensive weapon that was a crucial element of their success in past battles when the French cavalry launched frontal attacks.

About the same time the English archers took up their position, the French cavalry reached St. Peravy, which lay 1½ miles north of St. Sigismond and half a mile south of Talbot’s archers. The French cavalry might well have been caught off guard had it not been for an incident involving a large stag. Startled by the approach of the horsemen, the stag bolted from a grove of trees and ran into a group of English archers. The archers cried out and scrambled to get out of the frightened animal’s way.

Confusion in the English Ranks

The French horsemen at the front of the column heard the cries and spotted the English. They quickly sent word to La Hire that they had found the English and that the enemy was willing to give battle. La Hire ordered an immediate attack in the belief that one heavy blow would shatter the vulnerable English army.

At 2 pm, La Hire gave the order for the French to charge the English archers. The mounted men-at-arms kicked their horses in the sides and thundered toward the English archers, whom they outnumbered 3-to-1. The French cavalry slammed into the archers’ flanks, then surrounded the enemy bowmen. A few of the archers managed to escape the encirclement and head for the safety of Fastolf’s main line.

Fastolf had only partially finished his preparations when the clearly rattled archers came streaming back toward his position in small groups. Panic quickly spread through the part of Fastolf’s army known as the Paris Militia—green recruits from English-occupied France that Fastolf had brought along to flesh out his army. The Paris Militia were not the only ones in shock. Neither Fastolf nor his principal lieutenants had ever heard of such a bold French attack. Ironically, the French were using tactics previously used by Talbot, who had a reputation for carrying out swift, punishing raids. This time the tables were turned.

After swooping down on the English archers, the French cavalry under La Hire’s inspired leadership pressed its attack against Fastolf’s loosely organized line of battle. The defense put up by the French militia and other troops of limited experience and questionable allegiance was no better than that of the archers. French horsemen knocked down the defenders and poured through gaps in their lines. The defenders sought safety in small knots that were quickly surrounded by the French cavalry.

Talbot’s Fortunes of War

The battle lasted little more than an hour. English resistance was nonexistent by the time the forward elements of Alençon’s main force arrived on the scene in mid-afternoon. The only job left to them was to mop up after the French cavalry and join in the pursuit of those stray enemy soldiers who were fleeing for their lives in every direction. Joan arrived on the battlefield after the English had been vanquished. Spotting an English foot soldier who had been fatally wounded, she climbed down from her horse, knelt beside him, and cradled his head in her hands, receiving his confession before he went limp in her arms.

Talbot was captured behind a hedge and taken to a house in Patay, where he spent a long night listening to Alençon and other French captains celebrating their victory. He was treated for a nonfatal wound he had received in the back during the rout. The following day, Talbot had a brief visit from Alençon. Five years before, Alençon had been captured by the English at Verneuil and held in captivity until February 1429. Only recently had he been able to return to the battlefield. Alençon gloated to his prisoner over the pleasures of freedom versus the torments of imprisonment. Talbot told Alençon that it was merely the fortunes of war.

Abandoning their guns and baggage, Fastolf and his troops began a long march north with elements of the French army nipping at their heels. When French cavalry attempted to destroy them a second time, the veteran English longbowmen were able to drive them off. A weary Fastolf reached Janville in the black of night. To add insult to injury, the English found the townspeople there unwilling to admit them for fear of reprisal from the victorious French.

Fastolf and his band resumed their forced march northeast to Etampes and Corbeil, where Fastolf informed Bedford of the disaster that had befallen his command. The regent was furious and immediately removed Fastolf’s garter, the symbol of his knighthood. Although his garter was eventually restored, Fastolf had earned the lasting enmity of many of his compatriots, particularly Talbot, who never forgave him for failing to repulse the French at Patay.

Burned at the Stake

On June 29, a 12,000-strong French army escorted the Dauphin into formerly held English territory, where he was crowned king of France by the archbishop of Reims. Joan attended the ceremony wearing full armor and carrying her tattered battle standard. Soon, her influence at the French court waned considerably. Still eager to drive the English from French soil, Joan rode off the following spring to assist the French garrison at Compiegne that was under siege by English ally Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. The Burgundians captured her on May 23, 1430, and promptly sold her to the English. Accused of being a witch and a heretic by ecclesiastical officials loyal to the English, she was burned at the stake in Rouen on May 30, 1431.

The king for whom she had fought so hard, Charles VII, abandoned Joan in her hour of need, but the French people never forgot Joan of Arc. Six centuries later the Roman Catholic Church canonized her as a patron saint of France, and historians still recognize the untrained teenager from Domremy as one of the key military strategists of the Hundred Years’ War.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments