By 1944, the Japanese still had no long-range bombers to match the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. And a great many of Dai Nippon’s warplanes and aircraft carriers were lying at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. The few submarines that were still operating had long since been scared away from the West Coast of the United States.

Earlier, the Japanese had tried a few conventional attacks using long-range I-class submarines, but without much success. On the night of February 21, 1942, the I-17 shelled the California coast at Santa Barbara, where the Ellwood Oil facility stood. At least a dozen shells were fired from the sub’s 5.5-inch deck gun, damaging a storage tank and destroying a derrick and pump house. Although damage was minimal, the lone raider struck fear in the hearts of area residents and authorities, who thought it was the prelude to an invasion.

So panicky were the residents of Los Angeles that on the night of February 23-24, people claimed to have seen enemy planes over the city (it was actually just a weather balloon). The coastal defense batteries in the area began blasting the skies, but no enemy planes were within thousands of miles of the city.

The Japanese continued their submarine attacks, targeting merchant ships along America’s West Coast, but with little effect. In June 1942, two I-class subs prowled off the Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia coasts. On the 20th, the I-26 shelled the Estevan Point lighthouse on Canada’s Vancouver Island, and the I-25 shelled and torpedoed—but did not sink—a freighter off Cape Flattery, Washington. On September 9, a small plane catapulted from the deck of the I-25 and dropped an incendiary bomb in the thick forest of southern Oregon in hopes of starting a conflagration. All the bomb did was create a crater one foot deep and three feet in diameter.

The next night, the I-25 came in close to Fort Stevens, near Astoria, Oregon, at the mouth of the Columbia River. There, it began shelling the fort but did little damage; one baseball backstop on post was the sole casualty. The fort’s commander had his gunners withhold fire so as not to give their positions away.

As one historian put it, “It was the only hostile shelling of a military base on the U.S. mainland during World War II and the first since the War of 1812.”

Japan’s leaders were in a quandary. What could they do in order to strike back at the American homeland? The Doolittle Raid on Tokyo and other Japanese cities had taken place on April 18, 1942, prompting the Japanese to begin investigating novel ways they could retaliate.

Eventually someone came up with the idea of attaching bombs to balloons and allowing the recently discovered jet stream to carry them across the Pacific where they would explode over the United States.

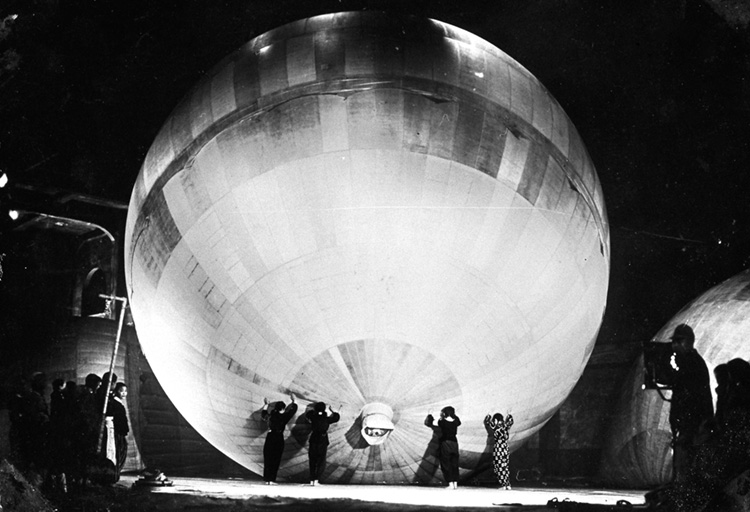

It was an ingenious idea, but many engineering obstacles had to be overcome. Among them were the types of materials needed to make such devices. The first balloon bag was made from rubberized silk, but due to wartime shortages of rubber, this was replaced by paper made from the fibers of the kozo bush, a member of the mulberry tree family.

These fibers were glued together with potato flour that made for a tough, canvas-like material. Schoolgirls were drafted to construct the balloons in seven factories (usually in theaters or large arenas) around Tokyo. Three industrial firms were contracted for the project: the Mitsubishi Saishi Paper Factory, Nippon Kakokin Company, and the Kokuka Rubber Company.

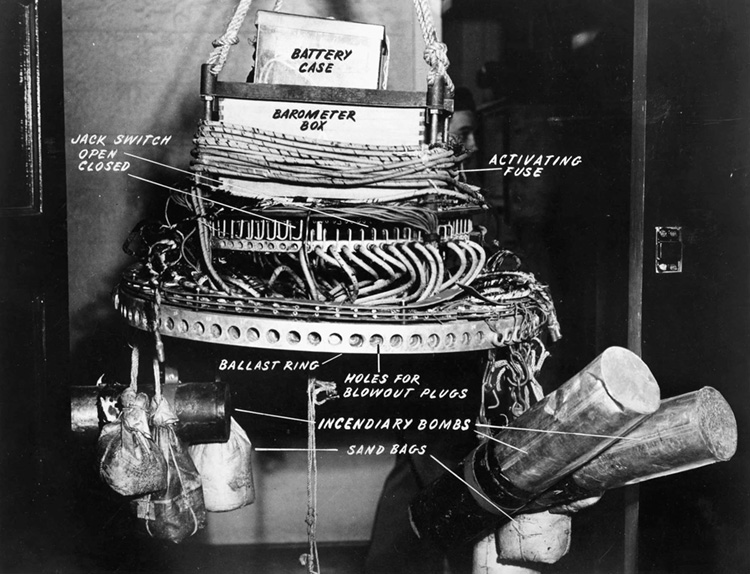

When inflated with hydrogen, the balloons grew to 33 feet in diameter. Hanging below the balloon from 19 50-foot-long shroud lines was an aluminum ring, or “chandelier,” to which was attached a control and ballast system consisting of 32 sandbags, as well as a payload: either a 32-pound anti-personnel device or two 24-pound thermite incendiary bombs.

The main problem was how to keep such a heavy balloon aloft for at least 70 hours over 6,000 miles of ocean. Scientists decided to employ an altimeter that would automatically respond to changes in air pressure.

A gas-discharge valve and ballast-release system were also integrated to maintain altitude during the long voyage. As hydrogen was depleted, the balloons would lose altitude, so the devices were rigged with barometers and timers to drop sandbags as necessary to keep the balloons aloft at 30,000 feet, within the flow of the jet stream.

The goal was to produce 10,000 balloon bombs, known as Fu-Go—or “wind-ship weapon”—that would be released, carried across the Pacific, and dropped into the United States with the hope of triggering massive forest fires and even, if they got lucky, starting fires in towns and cities, causing massive panic. The program was put into operation in time to catch the strong winter winds of 1944-1945.

Tom Crouch, chairman of the Smithsonian Institution’s Department of Aeronautics in Washington, D.C., said, “[The Japanese] wanted to set the Northwest on fire. It was a desperation move. They wanted to strike back at us for our aerial bombing raids.”

Eventually about 9,000 balloons would be launched by personnel of the Special Balloon Regiment from three sites on the lower half of the main home island of Honshu, some 5,000 miles from the California coast. If the weather was good and the winds favorable, 200 to 300 balloons could be launched each day. The first Fu-Go balloon launch took place in November 1944, and the devices took three or four days to make the trans-Pacific flight.

The majority of the balloons, however, would malfunction and land harmlessly in the ocean. On November 4, 1944, a U.S. Navy patrol boat spotted a mysterious object floating on the sea 66 miles southwest of San Pedro, California. When sailors hauled the object on board, they didn’t immediately recognize it as a weapon, despite the rising sun painted on the bag and Japanese markings elsewhere.

After the San Pedro discovery, balloon bombs began turning up in many places. On December 6, 1944, an explosion was heard near Thermopolis, Wyoming, and a bomb crater was later discovered. On December 11, an intact Fu-Go balloon was found near Kalispell, Montana. On the last day of the year, another balloon was discovered near Estacada, Oregon.

California was the landing place for at least a dozen balloon bombs. A 1994 Los Angeles Times story said that a “Fu-Go balloon bomb created a crater in the dry bed of the Santa Clara River near Saticoy on January 15, 1945. Two days later, an entire balloon was found in Moorpark, containing unexploded incendiary bombs but missing the 33-pound anti-personnel bomb carried by the balloons. Remnants of a third balloon bomb were found February 21 in Oxnard.”

On January 4, 1945, the Office of Censorship requested that publishers and radio broadcasters say nothing about the balloon incidents, hoping that the lack of news would cause the enemy to give up the Fu-Go campaign. As one historian wrote, “This voluntary censorship was adhered to from coast to coast, a remarkable self-restraint in a free-press-conscious country.”

Only about 10 percent of the 9,000 balloon bombs released successfully reached North America. Where they might land no one could say—or control. Some landed on the Aleutian island of Attu, while others dropped into northern Mexico. Canada also saw its share of the uninvited visitors.

On January 12, 1945, a 15-year-old boy in rural Milton, Saskatchewan, found an odd-looking object. He called his father and uncle over to check it out. They poked and prodded it, even kicked it. Luckily, it did not explode and was turned over to the authorities for safe disposal.

In January 1945, a balloon bomb exploded near Medford, Oregon, denting the ground with a shallow crater and shooting flames 20 feet into the air.

It wasn’t just the West Coast that was experiencing the attacks; twenty-six states would report balloons making landfall. In February 1945, a Fu-Go was found at Bigelow, Kansas. That same month, a balloon came down in a pasture near the small town of Laurens, north of Des Moines, Iowa. The farmer who found it tied it to the bumper of his car and dragged it into town, where curious locals cut off pieces as souvenirs. Seven balloons were reported to have come down in Nebraska, including one that exploded in Omaha on April 18, 1945, but caused no damage.

The balloon that is recorded to have travelled the farthest came to earth near Detroit, Michigan, but, like most of the others, did no damage. Another landed at Dorr, Michigan, a small town south of Grand Rapids. On February 23, 1945, three young boys—Larry Bailey and Ken and Robert Fein—saw something strange floating down from the sky. When it landed in a farm field, they raced over to see what it was.

Having no idea, they tried dragging it home but it was much too heavy. Along came neighbor Joe Wolf in his pickup truck. Wolf immediately sensed something was wrong and called the sheriff, who looked at it and then called the FBI, who took it away.

In March 1945 two balloon bombs came down in South Hill, Washington, near Tacoma. The first one landed on March 1 in a tree near today’s Pope Elementary School. The farmer who found it cut the balloon into strips and gave them to his children for keepsakes.

A second Fu-Go bomb landed in South Hill, Washington, on March 5 and exploded just south of the present-day intersection of 94th Avenue and 128th Street, near the current location of the Mormon Church and Rogers High School, causing no injuries or damage. Fragments of the bomb were retrieved by Army personnel from Fort Lewis, who came to secure the area.

On March 10, 1945, the Fu-Go campaign scored a “near success.” A power line at the top-secret atomic bomb production plant at Hanford, Washington, 210 miles southeast of Seattle, was struck by a Fu-Go bomb. The balloon destroyed a power line that supplied electricity to the building containing the reactor that was producing plutonium destined for the Nagasaki atomic bomb. The reactor was briefly shut down, but backup generators came online and restored power.

Thirteen days later, Desdemona, Texas, in rural Brown County, was the scene of another balloon discovery. Fourteen-year-old C.M. “Pug” Guthery was getting off his school bus when he saw a large object descending to earth. Chasing it for almost two miles, he finally caught up with it—along with several classmates.

Repelled by the contraption’s foul, creosote smell, Pug stood back while he watched the others vandalize it and remove pieces. The next day government officials arrived to look it over. They then went to the school to request that the students who took “souvenirs” return them. “The pieces were needed to reconstruct it,” Guthery said.

The next day, the rural town of Woodson, 60 miles northwest of Desdemona, was also “bombed” by a Fu-Go balloon. Ivan Miller, a cowboy on a ranch, was watching his cattle when he found a strange object in a field; the deflated bag had a large rising sun painted on its top. Within hours, school children arrived to gawk at the unidentified object and remove pieces as souvenirs. And, as at Desdemona, government officials showed up at school and requested the pieces be returned.

On March 19, 1945, the Swets family, farmers in Timnath, Colorado, 57 miles north of Denver, found themselves under attack by a Fu-Go bomb. Eight-year-old Jack Swets was in the corral near the family home when he heard a loud buzzing noise, followed by a ball of fire that hit close to where he stood, shooting flames 10 or 15 feet high into the air and damaging the family tractor.

He ran into the house to tell his father, John, what he had seen. John Swets then called the sheriff, who called in the FBI and the Army. A 2014 newspaper article said, “The Swets family was warned not to discuss anything about the incident, and newspaper reporters agreed not to run the story. One radio reporter was cut off in mid-sentence when he tried to broadcast from the farm.

“After the war ended, John Swets discovered a second bomb buried deep in a field on his farm, unearthed as he was plowing. Luckily, this bomb had exploded underground.”

The military had no idea from where these devices were coming, but quickly instituted air defense plans. Despite hundreds of planes on the lookout for balloons, only two balloons were ever shot down over continental North America; several were shot down over the Aleutian Islands.

To determine the location of the balloon launch sites, sand used as ballast was gathered from the downed balloons and analyzed by the U.S. Geological Survey. According to Dr. Clarence S. Ross, the sand in one sample was determined to be beach sand that came from the vicinity of Shiogama on the east coast of Honshu.

Other samples, Ross said, were likely to have come from Ichinomiya, about 40 miles southeast of Tokyo. However, before air raids against the probable launch sites could be mounted, the program came to an abrupt and unexpected end.

The termination of the Fu-Go campaign was not the result of military action but rather of censorship and silence. In an age when the U.S. government maintained tight control of war news, information regarding Fu-Go balloon activity in the U.S. was kept under wraps, giving the Japanese no indication that any of their balloons were hitting United States territory.

Operating with little hard information to go on, the Japanese claimed in propaganda radio broadcasts that the Fu-Go program was wildly successful—that the devices had started major fires in the U.S. and killed or injured 500 Americans. The broadcasts even fantastically threatened that soon millions of balloon-borne Japanese soldiers would invade the United States.

Realizing that the enemy was probably waiting to hear about the effects of the Fu-Go campaign, American officials hoped that their imposition of a total news blackout surrounding the balloon bombardment would cause the Japanese to stop releasing them.

The strategy apparently worked, because the last balloon launch took place on April 20, 1945. But there was still time for one more tragedy.

The only known case of a Fu-Go balloon causing fatalities occurred on May 5, 1945, near the small lumber-milling community of Bly, Oregon. The Reverend Archie and Elsye Mitchell had taken a group of children on a Sunday school picnic to Gearhart Mountain, where the children found an object amongst the trees. Without knowing what it was, the children began playing with it. Reverend Mitchell recalled, “I hurriedly called a warning to them, but it was too late. Just then there was a big explosion. I ran up—and they were all lying there, dead.”

Killed were Mitchell’s pregnant wife Elsye, 26, along with Sherman Shoemaker, 11, Eddie Engen, 13, Jay Gifford, 13, Joan Patzke, 13, and Dick Patzke, 14. They were the only civilians to die by enemy weapons on the United States mainland during World War II.

Decades after the war, Fu-Go balloons were still being found. In 1992, a balloon bomb was recovered in Jackson County, Oregon, about 100 miles west of Bly. And in 2014, loggers discovered an unexploded balloon bomb in Lumby, British Columbia, 200 miles northeast of Vancouver. A Royal Canadian Navy bomb-disposal team safely detonated it.

Bert Webber, an Oregon-based historian, noted, “There’s evidence indicating that [the Japanese] were ready to launch even larger balloons with larger bomb loads.” Attaching chemical and biological weapons to the balloons was also considered.

A report on the Fu-Go campaign by Robert C. Mikesh in the 1972 Smithsonian Annals of Flight concluded, “The greatest weakness of the free balloon as a military weapon is that it cannot be controlled. The balloon campaign was an interesting experiment, but it was a military failure.”

Story by Mason B. Webb