By Kelly Bell

By the late summer of 1944, the Third Reich was almost surrounded. Two years earlier Adolf Hitler had ground 10 European countries under his heel along with vast expanses of North Africa and Soviet Russia. The global union arrayed against him had now liberated nearly all of the conquered territory, as one after another the occupied nations and their capitals were retaken. As the summer waned, Hitler lost the first seat of government he had taken. After almost five years under a gray-brown Nazi yoke, Warsaw fell to the onrushing legions of Joseph Stalin as red became the new color of Poland’s captivity.

The Russian despot craftily let the Nazis do his dirty work for him. Anticipating the Red Army’s arrival, Warsaw’s resistance forces had launched a full-scale uprising against the Germans. Stalin paused. The Polish underground would be as big a headache for him as it had been for the occupying Nazis, so he ordered his generals to halt just east of the city, denying the guerrillas their anticipated support. By the time Stalin resumed his advance days later, the Wehrmacht had effectively destroyed Warsaw’s resistance movement. The Russians would not have to contend with it during their own occupation.

Hitler had always had a great deal of admiration for his Russian counterpart’s total ruthlessness, and he decided to emulate Stalin in the west, but for different reasons. With the Allies rapidly approaching Paris, the Führer decided that if he could not have the City of Light, nobody could. The free world’s forces would liberate nothing but smoking rubble.

Bypassing Paris

Allied Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower was also preoccupied with the French capital. Although he was now one of the most powerful men in the world, Eisenhower felt helpless and frustrated over what to do about Paris, Europe’s premier artistic and cultural center. He was under intense international pressure to liberate the city, but there were overriding logistical and tactical considerations that led him to postpone his armies’ advance.

Eisenhower had just read a 24-page report warning that the liberation of Paris would cut deeply into Allied resources and significantly delay the retaking of the rest of Nazi-occupied Europe. The biggest problem was fuel. The Normandy beaches were still the main offloading point for gasoline, ammunition, weapons, food, spare parts, medical supplies, reinforcements, mail, and all the assorted essentials needed the equip a giant army in the field. By August the front had moved so far east that truck convoys delivering supplies were burning more fuel than they were delivering. To increase the number of gasoline barrels would mean decreasing the volume of other supplies needed for the winter stockpile. The projected amount required before cold weather set in was 75,000 tons of food and medical supplies, as well as a 1,500-ton-per-day coal allowance.

There were also tactical considerations. Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) was hoping to establish a bridgehead over the Rhine before autumn rains slowed the advance. Concluding that the liberation of Paris could wait a couple of months, the high command came up with an alternate plan. British Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery’s 21st Army Group would launch a major attack eastward between the Seine and Oise Rivers and capture the port of Le Havre, giving the Allies a crucial new unloading point for supplies. The British would then overrun the V-1 and V-2 launching emplacements in Pas-de-Calais and secure Amiens. Meanwhile, the U.S. Twelfth Army Group would strike eastward, ford the Seine at Melun, swing north for 100 miles, veer westward at Reims, and link up with the British, who would be moving south from Amiens.

From a strictly tactical point of view, the new plan made sense. Paris’s German garrison would be neutralized by encirclement, avoiding an intense urban battle (which would have suited Hitler’s destructive aims). The terrain was suitable for self-propelled armor, and increasingly scarce gasoline would be saved for the assault on the Siegfried Line guarding Germany’s western frontier. The operation was tentatively set to commence sometime between September 15 and October 1.

De Gaulle’s Political Concerns

Eisenhower considered the plan an acceptable alternative to a direct assault on Paris proper, but Free French leader General Charles de Gaulle did not. From the war’s outset, de Gaulle’s relations with the Americans and British had been fractious. There was persistent friction between him, American President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill. De Gaulle had been rankled by American recognition of France’s collaborationist Vichy government and by not being informed of the impending American landings in North Africa in the autumn of 1942.

Europe’s complex political situation gave de Gaulle other problems to consider. Determined to save his country from becoming a postwar bulwark of European communism, the French leader had detailed spies to infiltrate the country’s predominantly left-wing resistance movement. When his operatives informed him that the Red underground was planning a major insurrection to liberate Paris and establish communism as the country’s dominant faction before the Allies could arrive, de Gaulle realized that the immediate liberation of Paris was crucial to Western Europe’s postwar political future—as well as his own. His intelligence sources reported that the Communists had approximately 25,000 armed irregulars in the capital; they now outnumbered the Germans. There was a very real possibility the leftists could defeat the Nazis by themselves, taking over the government and likely setting off a ruinous civil war with de Gaulle’s supporters. Drained by four years of Nazi occupation, France was in no condition to endure the rigors of a major internecine conflict.

From his headquarters in Algiers, de Gaulle ordered a halt to all airdrops of supplies into the city and the surrounding area. He commenced sending his most trusted subordinates into Paris to persuade as many resistance units as possible, regardless of their political inclinations, to hold off attacking the Germans until he could convince the Allies to resume heading for the city. Hitler, meanwhile, was making his own preparations.

The Disillusioned Dietrich von Choltitz

Hitler was one of the multitudes of German soldiers who had been left emotionally and physically scarred by their failure to take Paris in World War I. Two million of his comrades had perished in the miserable trenches on the Western Front. None of his later conquests had thrilled Hitler as much as the capture of Paris, and accordingly he was obsessed with defending his conquest. Hitler resolved that if the fall of Paris appeared imminent, he would destroy the city.

Hitler’s new man in Paris, Maj. Gen. Dietrich von Choltitz, was fresh from three years of illustrious service on the Russian front, where he had earned a reputation for competence, aggressiveness, and absolute obedience. His standing as an officer who would ruthlessly obey any order made him one of the few members of the general staff whom Hitler was willing to trust following the July 20 attempt on his life. Born into an old family with a long tradition of military accomplishment, Choltitz was a typical Prussian martinet. He expected blind obedience from his subordinates, and his superiors could expect it from him. Orders were not to be questioned but carried out immediately.

Choltitz’s service earlier in the war had been both exemplary and heartless. In 1940 he commanded the bomber formations that incinerated Rotterdam before the Dutch had time to surrender. His tenacity and resourcefulness were evident during the grisly July 1942 siege of the Crimean port of Sevastopol, when he lost so many troops from his 4,800-man regiment that he was forced to use Russian POWs to carry and load shells for his artillery pieces. Ignoring a gushing arm wound, Choltitz steadfastly continued to pressure the city until it surrendered. By then, all but 347 of his own men were dead. When the war in the East turned against the Germans, Choltitz was transferred to Army Group Center. As the Wehrmacht steadily retreated westward, he ruthlessly carried out Hitler’s scorched-earth policy, making certain that the Red Army found nothing but charred ruins as it advanced.

The diminutive general was an accomplished vandal, but by August 1944, when he arrived in Paris as its new military governor, Choltitz was beginning to have second thoughts about mass, wanton destruction. He met Hitler for the first time at an outdoor luncheon in the summer of 1943 when the Nazi leader toured the Russian front. He believed it when the Führer assured all in attendance that the gargantuan Red Army would be bled white as it advanced into the teeth of tenacious German resistance. After a year of waiting vainly for this to happen, Choltitz had become disillusioned.

Ordered to Destroy Paris

Summoned to Hitler’s East Prussian headquarters one year later, Choltitz was shocked at the dictator’s physical and mental deterioration. After a rambling monologue on his own life’s accomplishments, Hitler concluded with an hysterical diatribe against the Prussian officer corps. He concluded by informing Choltitz that he would be posted to Paris to brutally stamp out “all civilian acts of disobedience or terrorism.” As he left the secluded forest compound, Choltitz was less than reassured. It seemed as though he was being given another scorched-earth assignment. Yet this time it was not some nameless, nondescript little burg on the endless Russian steppes. It was Paris, the most artistic, cultured and beautiful city in the world. For the first time in his life, Choltitz thought of disobeying a direct order.

Departing East Prussia, the general happened to take the same train as the director of the German Worker’s Front, Robert Ley. As the two men gossiped over cigars, Ley informed Choltitz that Hitler had just exhumed an ancient German law that essentially held soldiers’ families hostage. Prompted by the July bomb plot on his life, the revived legislation decreed the death penalty for the loved ones of any servicemen who deserted, surrendered, committed treason or suicide, or merely performed at levels below what their superiors considered acceptable. Stunned and sickened, Choltitz muttered that Germany was reverting to Middle Ages barbarism. Ley replied, “Yes, but these are exceptional times.”

The next morning the train stopped over in Choltitz’s hometown of Baden-Baden, allowing him a brief reunion with wife Uberta, daughters Maria Angelika, 14, Anna Barbara, 8, and infant son Timo. The previous night the train had passed through Berlin, and during a fleeting stop to take on passengers a courier had arrived, informing Choltitz of his promotion to general and handing him two new bars for his shoulder tabs. As Uberta sewed them onto his tunic, she and the children could sense the tension and foreboding he silently radiated. Meanwhile, back in East Prussia, Hitler had ordered all available reinforcements sent to France. He sullenly added: “Why should we care if Paris is destroyed? The Allies, at this very moment, are destroying cities all over Germany with their bombs.”

Mayor Tattinger’s Plea to Save Paris

Upon arrival at his new command, Choltitz was ruefully unsurprised when Lt. Gen. Gunther Blumentritt informed him that the German garrison had been ordered to carry out a citywide orgy of destruction if compelled to abandon Paris. The 813th Engineer Company was already sowing explosives at prearranged points. Although water and electrical facilities were priority targets, the engineers began by mining the ancient bridges across the Seine. With these lovely old spans destroyed, any advancing army would have great difficulty fording the broad, winding river. The Nazis also mined the 400-year-old Palais de Luxembourg, with its priceless collection of art and literary works. They also fixed charges in the Chamber of Deputies, the French Foreign Office, the telephone exchanges, the railroad stations, aircraft plants and every factory in the city.

Choltitz was running out of time. On August 17, he received a cable from Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge that included the words, “I give the order for the neutralization and destruction envisaged for Paris.” Choltitz was increasingly desperate to abort the most heinous act of mass vandalism in history, knowing that his name would be eternally defaced as a result. Yet he still had the ingrained inclination of a professional Prussian soldier to unquestioningly do as he was told.

To the west of the capital, Lt. Col. Hubertus von Aulock was laying out a defensive perimeter in a 60-mile arc in front of the encroaching liberation forces. Aulock and Choltitz both knew that the 10,000 men available for the line were woefully insufficient, but Berlin had promised them reinforcements. Realizing that there was little chance the Allies would launch heavy bombing raids on Paris, Choltitz resourcefully removed all 88mm antiaircraft pieces from the city and placed them as antiarmor artillery at intervals along the defense line.

Meanwhile, sappers were priming hundreds of U-boat torpedoes and stacking them in a tunnel underneath the heart of the city. If detonated, they would leave the center of Paris a smoking wasteland. Mayor Pierre Charles Tattinger, alarmed at all the ordnance being sown throughout the city, paid a visit to the harried Choltitz. Demanding an explanation, the Frenchman was not reassured by the German’s response: “As an officer, Monsieur Tattinger, you will understand there are certain measures I shall have to take in Paris. It is my duty to slow up as much as possible the advance of the Allies.”

Although a collaborator who had spent the past several years working closely with the Nazis, Tattinger had not realized until now how far they were capable of going with their atrocities. This was Paris—how could they consider such a crime against civilization? At this point the asthmatic Choltitz was taken with a violent coughing attack. Under the pretense of helping him catch his breath, Tattinger led the general to a window overlooking the immaculately sculpted gardens of the Tuileries, the Rue de Rivoli, Notre Dame, the Seine, Les Invalides and, in the near distance, the Eiffel Tower. “Often it is given a general to destroy, rarely to preserve,” said the mayor. “Imagine that one day it might be given you to stand on this balcony again, as a tourist, to look once more on these monuments to our joys, to our sufferings, and be able to say, ‘One day I could have destroyed this, and I preserved it as a gift to humanity.’ General, is not that worth all a conqueror’s glory?”

Choltitz looked to his left at the Louvre, then to his right at the Place de la Concorde, and said: “You are a good advocate for Paris, Monsieur Tattinger. You have done your duty well. Likewise I, as a German general, must do mine.” Would he do his duty as a Nazi soldier, or as a civilized human being? He had little time to decide, for within the city the pace of events was quickening.

“Paris is Worth 200,000 Dead”

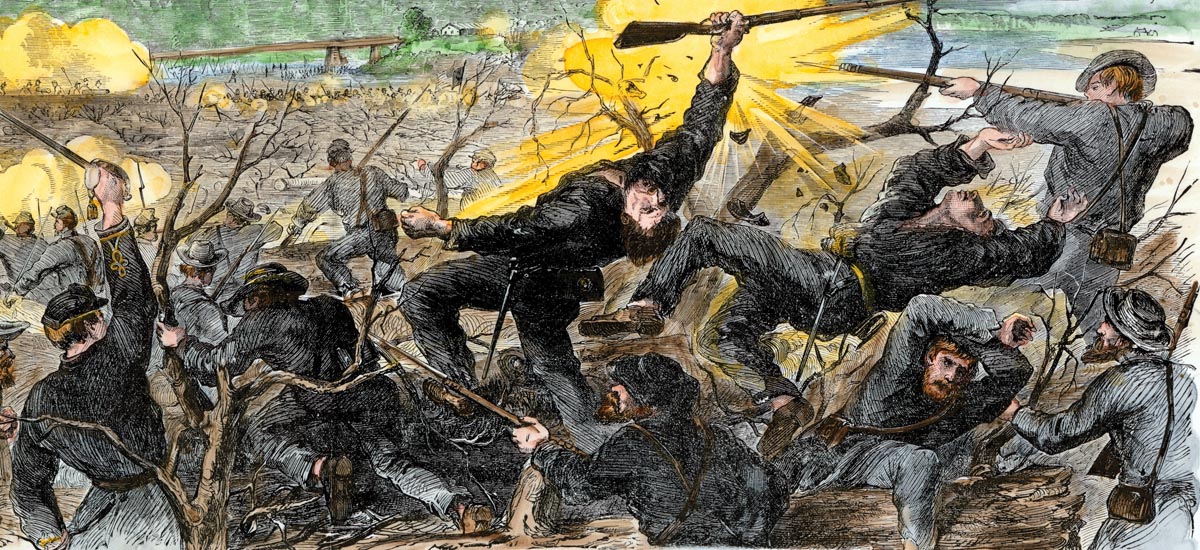

On August 19, de Gaulle unleashed his own underground forces on the Germans before the Reds could fully deploy. Across the capital Gaullist troops assailed Nazi fortifications and troop concentrations. The Reds wasted no time joining in. Resistance forces armed with Molotov cocktails, fowling pieces, World War I-surplus Lebel rifles, and slow-firing Hotchkiss machine guns all went into action. Destruction in the city mounted as the Germans responded.

With the police prefecture at the heart of the fighting, Choltitz deployed tanks and dive bombers to attack at first light on August 20. He outlined this strategy to the Swedish consul Raoul Nordling, who was also eager to halt the spreading damage. He suggested Choltitz offer a ceasefire to the encircled irregulars in the prefecture. The general found the proposal appealing. This way he would not besmirch his name by sending forces to fight in the heart of Paris. The truce was also a blessing for Charles de Gaulle. He learned of it just as he was leaving for a conference with Eisenhower, who was already angry about the situation.

Poorly informed on the politics behind the uprising, Eisenhower assumed that de Gaulle had launched the insurrection specifically to set himself up as France’s postwar head of state. The American, British, and Free French forces approaching from the west would have to hurry to rescue the partisans from being wiped out and Paris from going the blazing way of Warsaw. Yet if he did rush to the city, the liberation of the rest of Western Europe would be interrupted, prolonging the war for months. Even after Eisenhower learned that de Gaulle was not directly responsible for the resistance uprising, he was still aggravated, grumbling that de Gaulle was “trying to get us to change our plans to accommodate his political needs.” Still, without the imperious general, postwar France would almost certainly become a bastion of European communism. Nobody else within the country had the stature to stand up to the Reds.

The Allies’ most immediate concerns were tactical. Despite de Gaulle’s threat to withdraw the 2nd Free French Armored Division from the bulk of the Allies’ forces and send it on to Paris alone, Eisenhower initially stuck to his intended strategy. The day before the conference he had received an intelligence report that Hitler was transferring occupation forces from Denmark to help defend Paris. Meanwhile, in the city, the head of the communist underground, Henri Tanguy, alias “Colonel Rol,” was doing his best to disrupt the truce with the Germans and prevent de Gaulle from claiming credit for liberating the capital. Excoriating the cease-fire as a right-wing ploy to “exterminate the working class of Paris,” Tanguy ordered continued all-out attacks on German forces within the city regardless of losses to his own command. “Paris,” he declared coolly, “is worth 200,000 dead.”

Conflict Between the Communists and Gaullists

By the evening of August 20, the truce was over as open warfare had broken out citywide between communist insurgents and German occupation troops. By midnight Tanguy had lost 106 men, and an indeterminate number of Germans were dead. Choltitz was on the brink of launching a destructive counterattack on the partisans and commencing Hitler’s orders for mass demolitions. Then something unexpected happened.

An SS patrol arrested three resistance officers driving a car crammed with weapons and classified documents. They were Gaullist agents, calling themselves “ministers of de Gaulle.” The commanding SS officer, realizing the implications of this development, immediately contacted German headquarters and reported the arrest. It was indeed significant. One of the men was de Gaulle’s ranking representative in occupied France, Alexandre Parodi, who was quickly ushered into Choltitz’s presence.

After meticulously summarizing the implications of the dying truce, Choltitz released the three stunned Frenchmen in hopes that they could restore the truce. The Gaullists had a prearranged plan code-named Operation Prise du Pouvoir in place for such a situation. Every minister in de Gaulle’s London-based government-in-exile had a carefully screened and briefed counterpart secretly based in Paris. Calling them together, Parodi began installing them in their designated ministries. Parodi managed to assemble an ad hoc cabinet in the Hotel de Matignon, which he intended to make the temporary seat of government and declare the assembly the legitimate government of France. Like his chief, he was hoping to beat the Reds to the draw.

Tanguy’s representatives met with the Gaullists in an apartment overlooking the Parc Montsouris. The conference was predictably stormy. Making it clear that they were going to continue attacking the Nazis, the leftists threatened that if de Gaulle refused to join the uprising, they would plaster every building and wall in the city with placards revealing his inaction and accusing him of “stabbing the people of Paris in the back.” The fighting was too far progressed to stop now, they said. The truce was dead.

A Change in Plans: The Angl0-American Liberation Army

While the resistance commanders inside Paris squabbled, the leader of the 2nd Free French Armored Division, General Jacques Philippe Leclerc, was 122 miles to the west, mobilizing his 16,000 men for the first Allied advance on Paris. Dependent on the Americans for supplies, Leclerc had craftily ensured he would be equipped for the offensive by failing to report losses suffered in battle. He was still drawing fuel and ammunition allotments for tanks and other vehicles that he no longer possessed. Learning of the situation in the capital, he had spent the previous three nights sending out foraging parties to steal additional gasoline and ammo from U.S. supply depots.

Leclerc contacted Eisenhower’s headquarters in a futile attempt to obtain official permission to advance. During the early hours of August 21, he moved out on his own authority. Inadvertently, his enemies were making his coming assault easier for him. The reinforcements from Denmark were deployed south of the city, where the Wehrmacht high command anticipated the Allies would launch their main offensive. Choltitz mistakenly interpreted this to mean there would be little for his forces to defend—and he should destroy Paris before the Allies could get there.

A young Gaullist operative named Roger Gallois drove into American lines and roused Lt. Gen. George Patton in the middle of the night, imploring him to send his Third Army directly to Paris. Hamstrung by Eisenhower’s orders to the contrary, Patton lacked the authority to comply, so Gallois jumped back in his jeep and raced farther west to Twelfth Army Group headquarters. Arriving at 6 am on August 22, he cornered intelligence officer Brig. Gen. Edwin Sibert. With tears streaming down his face, Gallois begged the Americans to hurry to Paris while there was still time. His desperate pleas convinced Sibert, who resolved to make his own appeal to Eisenhower. The supreme commander, meanwhile, had already changed his mind about bypassing the city. Ensconced at his new command center in the town of Grandchamp, Eisenhower had caved in after receiving another desperate message from de Gaulle. A massive Anglo-American liberation army would be following immediately in the wake of the French.

Stiff Resistance Around Paris

Back in the city, both Gaullist and communist rebels were running low on ammunition while the Germans, so far untroubled by Allied ground forces, were able to concentrate all their efforts on the resistance fighters. The inner city steadily came to resemble Warsaw, with the French death toll climbing to 500. Nazi engineers continued to plant their explosives, mining the basement of Les Invalides. If these explosives detonated they would pulverize the French Army Museum, military art gallery, 400-year-old army barracks, and Napoleon’s tomb. Early on the dreary morning of August 23, four SS sappers were checking for the best spots to set off charges on the supports of the Eiffel Tower.

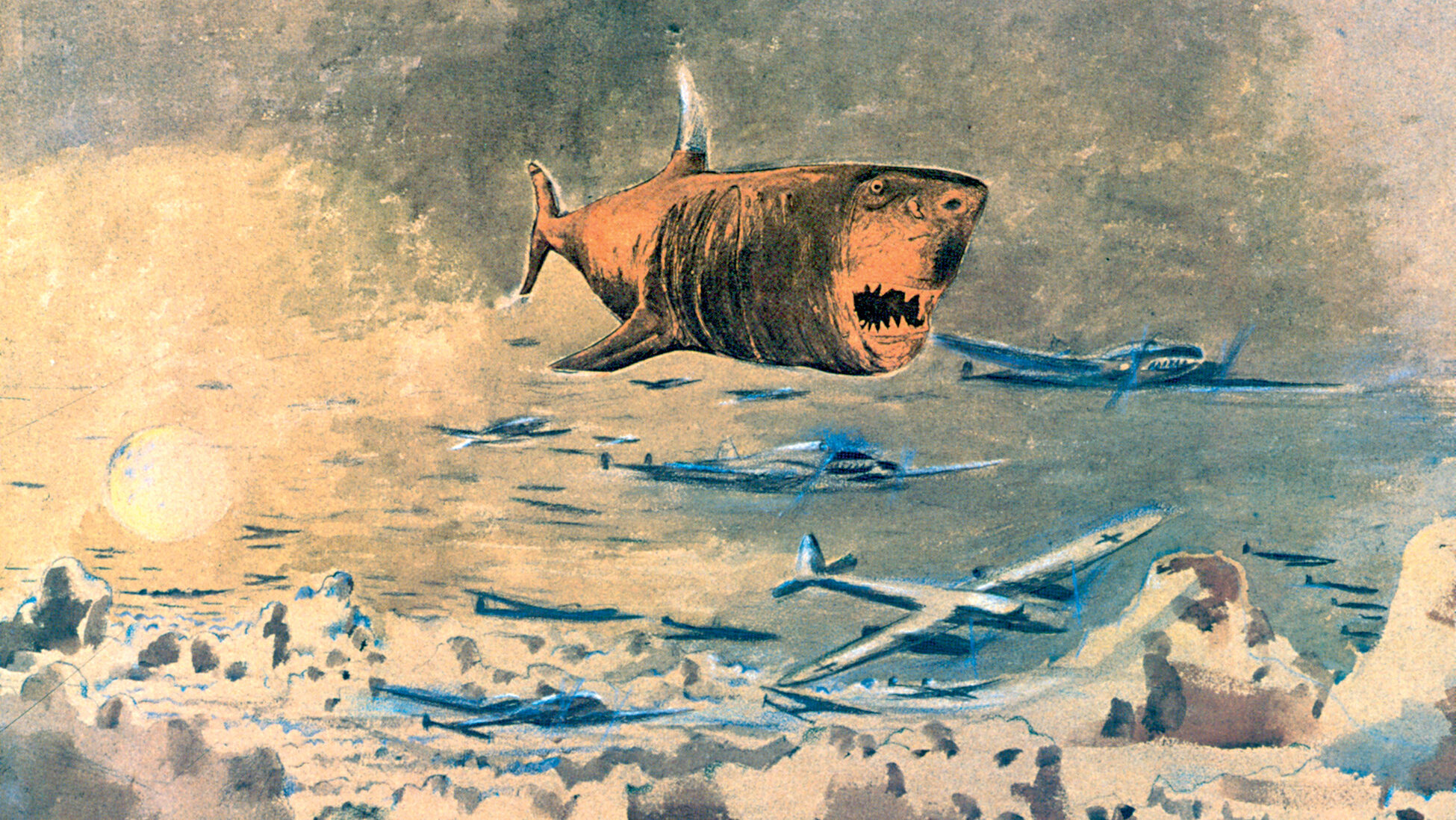

By this point the urban warfare was dying down as resistance fighters ran out of ammunition and went into hiding. They had done their jobs. German troops in the city headed for the defensive perimeter west of the outskirts, but they had already spent too much time preoccupied with the rebels. The 2nd Free French and U.S. 4th Infantry Division were already bearing down on the German defenses. The Nazis managed to redeploy their lethal 88s, and as the 2nd Free French neared, the flak guns opened a deadly fire.

The Luftwaffe was slated to assist in the supposed demolition of Paris by launching a major bombing attack on the city on the night of August 24-25. Again Choltitz came to the rescue. Storming into the sector’s ranking Luftwaffe office, he bellowed that there would be no such raid. The scheduled bombing targeted neighborhoods where large numbers of his soldiers were deployed. Such an air attack, yelled Choltitz, “would kill as many Germans as Parisians.” The raid was canceled.

War correspondent and self-appointed resistance fighter Ernest Hemingway had scouted the thoroughfares leading into the city and reported them clear of mines, but he failed to notice the camouflaged artillery emplacements. The haystacks in wheat fields bordering the roads concealed the guns of the 11th Flak Regiment, and as the Shermans passed the pastures, the 88s opened a murderous barrage. The French tankers would not be deterred. Frantic to be the first liberation unit to reach Paris, they disdained evasive maneuvering and charged directly into the artillery with no regard for losses. Firing on the move, they knocked out, ran over, or bypassed every 88 and continued their eastward dash. These tactics were costly, but they saved time.

By now shellfire from the west was audible in Paris, emboldening the partisans to resume scattered attacks on the Germans and forcing them to fight on two fronts. Realizing the Allies’ arrival was imminent, the Nazis commenced burning sensitive and incriminating documents. They had much to erase, for they had murdered 4,500 Frenchmen in the Gestapo prison of Mont Valerian alone.

Encouraged by the ever-nearing crash of artillery, the rebels began to disrupt the laying of demolitions and removed many of those already in place. When a six-truck German convoy packed with explosives set out for the Chamber of Deputies, the Gaullists and communists joined forces, attacking and destroying every vehicle.

American General Omar Bradley, overseeing the final push, had been under the misconception that the approaches to Paris were lightly defended, but as his troops and the Free French reached the suburbs, they met occasional but violent resistance. The 2nd Armored Division, in the vanguard, took the brunt of the opposition. When Bradley began to receive reports of the horrific losses the Frenchmen were absorbing, he hurriedly ordered the 4th Infantry Division to pick up the pace. As the Americans caught up with Leclerc on the evening of August 24, he had his aide, Captain Raymond Dronne, change into civilian clothes and sneak into the city to inform the freedom fighters that they would see liberation either that night or the next day.

At this point Choltitz again became the enemy. Although the diminutive Prussian was determined to abort the scheme to capriciously destroy Paris, he had no intention of giving up the city without a fight. He was a professional soldier who would not lay down his arms until it was the only remaining option. On the evening of the 24th, he informed his assembled staff that he would “personally shoot, in my own office, the next man who comes to me suggesting we abandon Paris without a fight.”

“Brennt Paris?”

Three hours later, at 9:30 pm, Leclerc’s command rumbled into the heart of the city. Against a backdrop of deafening cheers and unending strains of the French national anthem, ecstatic Parisians pulled the grimy, exhausted tankers from their machines. The victory celebration also drowned out occasional waves of gunfire, but it was little more than a mopping-up operation as most of the remaining 20,000 German troops in the city were soft and complacent following four years of easy occupation duty and were unwilling to fight a professional army. They eagerly surrendered, and at noon on August 25 the tricolor fluttered from atop the Eiffel Tower. Back in the gloomy woodlands of East Prussia, an agitated Hitler repeatedly asked his chief of staff, “Brennt Paris?” No, Paris was not burning.

Chotlitz resigned himself to his impending surrender. Just after 1 pm the next afternoon, one of Leclerc’s junior officers strode into his office and announced, “I am Lieutenant Henri Karcher of the army of General de Gaulle.” Rising from his desk, the German replied, “General von Choltitz, commander of Gross Paris.” “You are my prisoner,” said Karcher. Choltitz agreed. Karcher had barely enough men to protect his captive from being lynched by a mob outside the building, but they managed to reach a staff car with the Nazi’s only injuries being a few scratches and bruises.

The car hurried to the Hotel de Ville, where Leclerc had set up his temporary headquarters. Choltitz signed a formal surrender document and spent the next three hours cooling his heels. At 4:30 pm, a three-car convoy stopped outside the hotel and General de Gaulle stepped from the center vehicle. When he read the capitulation document he flushed with anger. Tanguy had managed to reach the building before him and signed the document first so that his name would appear before de Gaulle’s.

De Gaulle’s Political Victory

In the end, Tanguy would be the one to fade into obscurity while his rival took the reigns of government. De Gaulle was the centerpiece of the ensuing victory parade, his massive frame accentuating his magnetic presence as he towered over his companions. When a would-be assassin opened fire on him from one of Notre Dame Cathedral’s towers, de Gaulle earned the eternal awe and hero-worship of his countrymen by disdainfully ignoring the hail of bullets while everyone else dropped to the pavement. The gunman turned out not to be a German, but one of Tanguy’s leftist partisans. This infuriated many Frenchmen and turned them eternally against communism. Following his fearless stroll down the Champs Elysees, de Gaulle further ensured that there would be no leftist takeover by reading a “Proclamation of the Republic” to the adoring throng.

Things were not so jubilant in Germany. A hasty court-martial assembled to try Choltitz in absentia for treason, but some of the defendant’s highly placed friends were able to delay the hearing until the war ended before a verdict could be reached, thus saving Frau von Choltitz and her children from execution or exile to a concentration camp.

Others were not so lucky. By diverting their forces to Paris, the Allies depleted their fuel reserves and were unable to reach the German frontier before winter. Surviving Wehrmacht units were able to man the formidable Siegfried Line, and the arrival of a brutally cold and wet winter caused the Western Front to stagnate, giving Hitler time to make the final months of the war the costliest yet for the Allies. The Germans used the respite well, deploying over 600,000 men for the Battle of the Bulge, fortifying the Hürtgen Forest, and crushing the British at Arnhem. Unutterably worse was the delay in liberating the concentration camps in Eastern Europe. Millions of innocents died miserably in these hellholes before rescuers could reach them. Only after the war would the world comprehend the truly ghastly price of stopping first to save the City of Light. n

Join The Conversation

Comments