By Sam McGowan

In May 1942, the 27th Bombardment Group transferred from Batchelor, Australia, to Hunter Field outside Savannah, Georgia. It was a transfer without men or equipment to the same base from which the group had departed in October 1941 for the Philippine island of Manila. A relatively new unit, the 27th had been formed in February 1940 with personnel from the veteran 3rd Bombardment Group. Both units were based at Hunter and were the U.S. Army Air Corp’s only combat groups with a ground attack mission.

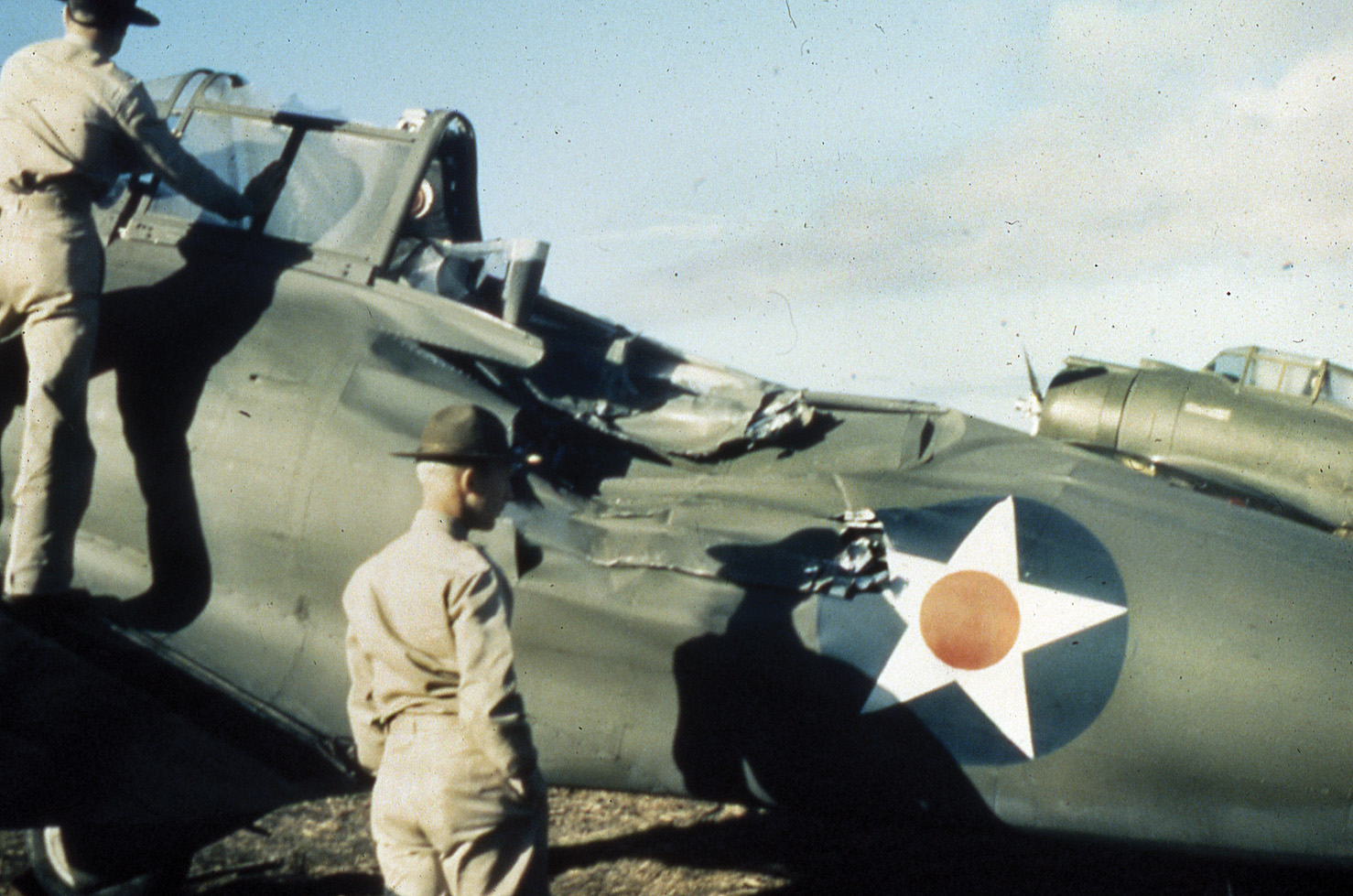

While the 3rd, which had formerly been designated as the 3rd Attack Group, operated Douglas A-20 twin-engine light bombers, the 27th reequipped with single-engine Douglas A-24 Banshee dive bombers based on the success of the German Junkers Ju-87 Stuka in Europe. The A-24 was basically the same airplane as the Navy’s Douglas SBD Dauntless, except that it was not designed for carrier operations and lacked a tailhook. The rear tire was pneumatic rather than solid as were the tailwheel tires on Navy and Marine aircraft.

The men of the 27th arrived in Manila on November 20 as part of a reinforcement the Army had codenamed Plum. The 27th was one of four Air Corps units that left Hawaii on the transport SS Coolidge along with SS Winfield Scott on November 6, escorted by the cruiser USS Louisville. Although the United States was not at war, tension with Japan led to the crossing being made under blackout conditions. The other units on the ship were the 5th Air Base Group, headed for Mindanao, and the 21st and 34th Pursuit Squadrons from the 35th Pursuit Group, whose headquarters left in a later convoy.

As soon as the group arrived in Manila, its commander, Major Reginald Vance, was moved to the headquarters of the Far East Air Force as chief of intelligence. The assistant group commander, Major John H. Davies, nicknamed “Big Jim,” was given command. He was told that the 27th’s A-24s would be arriving by ship in mid-December.

Since they had no airplanes, the 27th Group set up a temporary facility at Fort McKinley, the Army post adjacent to Nichols Field. Since it was temporary, they threw up some tents on the parade ground. Once their airplanes arrived, they would move the airfield at San Marcelino on Subic Bay at the head of the Bataan Peninsula. It was a primitive field that backed up to the mountains and was surrounded by brush and trees. Major Davies sent a detachment to work on the strip and start constructing quarters, wooden frames over which tents could be stretched. The rest of the group remained at Fort McKinley with nothing to do. They were finally put to work filling sandbags for revetments at Neilson Field.

It is likely that it was during this assignment that Major Davies and other officers in the group became acquainted with a local civilian pilot by the name of Paul I. Gunn. Gunn was a retired U.S. Navy pilot who was running the fledgling Philippines Airlines from its hangar at Neilson. Davies would later state that Gunn “joined the group in December,” but he was only speaking figuratively because until early April 1942 his role was as commander of all air transport in Australia.

Sometime after its arrival, the group was given four nearly worn-out Douglas B-18s so the crews could get in flying time and start becoming familiar with the area. Since the B-18s were twin-engine airplanes and the pilots had been flying single-engine A-24s, the flights were somewhat hairy. Officially, the B-18s belonged to the 19th Bombardment Group, which required one of their pilots to be on all flights. They flew back and forth between Neilson and their new bases at San Marcelino and Clark Field, which lay some distance north of Manila.

Far East Air Force commander Maj. Gen. Lewis Brereton made it clear that war could break out at any moment. On December 6, Philippines time, Colonel Harold George, commander of V Fighter Command, told the pursuit pilots at Nichols Field in no uncertain terms that war with Japan could start at any moment. He also advised the young pilots that they were in a desperate situation, although it was not quite suicidal. The fighter pilots were already standing strip alert by their airplanes, and at least one squadron had been launched to intercept a formation of unidentified airplanes that was picked up on radar by the new site that had just been installed at Iba on Luzon’s west coast.

Since the 27th’s airplanes were yet to arrive, the group had no mission. Davies had been informed that the A-24s were en route, but until then there was nothing they could do except work on their new base at San Marcelino and help out around Fort McKinley and Neilson Field. On Sunday, December 7, 1941, the group’s officers hosted a dinner at the Manila Hotel for General Brereton. Although Brereton attended the party, he had other things on his mind. He had been told by Admiral William P. Purnell, the senior naval officer in the Philippines, and Brig. Gen. Richard Sutherland, MacArthur’s chief of staff, that the Navy and War Departments feared that war was imminent. After leaving the party, which continued until 2 am, Brereton called his staff together and placed all the airfields on alert.

The Japanese attack came on December 8, Philippines time. Word of the attack on Pearl Harbor reached Manila in the wee hours of the morning, but no specific orders came from Washington for any military action against the Japanese on Formosa. As a safety measure, the 19th Bombardment Group ordered all of the B-17s bombers from the two squadrons at Clark to take off so they would not be caught on the ground by a surprise air attack. Two pursuit squadrons were launched; one from Clark was sent north to attempt to intercept a formation of Japanese bombers that eventually attacked Baguio in the northern mountains, while another came up from Nichols to provide air cover over Clark.

Later in the morning, Brereton received authorization for the B-17s to attack Formosa, and a recall order was sent for them to return to Clark to refuel and arm. The 20th Pursuit Squadron, which had been sent north to Rosales earlier in the morning, returned to Clark to refuel. The squadron was lined up at the end of the runway and beginning to take off when Japanese bombs began falling. Four of the Curtiss P-40 fighters were already airborne, but the rest of the squadron was caught in the bottom pattern.

The two squadrons of B-17s were still refueling and rearming. Although they escaped bomb damage, strafing Japanese fighters destroyed or damaged all but three of the B-17s. The Far East Air Force (FEAF) was not wiped out on the ground at Clark, but half its bomber force and most of a squadron of P-40s were. A number of other P-40s were lost that day due to engine problems and fuel starvation. Over the next week FEAF would continue suffering major losses. The majority were due to operational causes rather than enemy action.

The 27th played no part in the air battles in the Philippines simply because they had no planes. Some men served with antiaircraft batteries, and one contingent of 12 of the most experienced pilots was sent to Clark to reinforce the pursuit squadrons that had been moved there. However, those pilots were assigned to ground duty when they arrived.

On December 17, word reached FEAF headquarters that the convoy that had been bringing the 27th’s airplanes had been diverted to Australia. Eighteen P-40s were also on the same ship. Major Davies was authorized to take three airplanes from the pool of C-39s and B-18s that had been assigned to Nichols Field and go to Australia to pick them up. He personally picked 20 pilots and met with them that afternoon at the 27th headquarters at Fort McKinley. They gathered around a table laid with maps, on which Davies outlined the route south to Australia and the proposed return route through the Netherlands East Indies. He advised his men to take no more than 30 pounds of belongings with them and ordered them to tell no one where they were going.

At 8:15 that evening, the group left Fort McKinley for Nichols Field in four sedans. The route took them through the village of Baclaran, which had recently been bombed. Dozens of Filipinos had been killed, along with a number of animals, and the stench from rotting bodies was appalling. They spent several hours in a bombed-out barracks then were awakened at 3 am to go to the field. They learned that Captain Grant Mahony, a veteran pursuit pilot who had already made a name for himself, was going with them.

After arriving in Darwin, Australia, Major Davies made arrangements for the three transports to fly back to the Philippines with loads of badly needed .50-caliber ammunition. It was not until December 23 that transportation to Townsville and on to Brisbane was arranged for them on a Quantas Airways flying boat. They finally landed on the Brisbane River on Christmas Eve. They were taken by taxi to the Lennon Hotel, where they found beds with fresh linens and decent food.

Davies and his men expected to find their airplanes unloaded, assembled, and ready to go back to the Philippines. What they actually found was a state of confusion. No U.S. military organization existed in Brisbane, and there were no teams of mechanics to assemble the airplanes. The 18 P-40s that had come over were offloaded from the ship and the crates unceremoniously stacked on the docks. No one even knew they were there until several days later when Captain Gunn located them on the docks.

On Christmas Day, Gunn left Manila in one of his Beechcraft planes with a load of FEAF staff officers. General Brereton and his senior staff had left the day before in a Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat. Two more Beechcraft planes left Manila on New Year’s Eve and January 2, carrying pursuit pilots who had been selected for evacuation.

At some point Gunn became involved with the 27th Group pilots and more or less adopted them as his own. For the next four months he spent a good part of his time with them when he was not flying transport missions. There were no mechanics in the 27th Group party, but Gunn, a former U.S. Navy enlisted pilot, had been an aircraft mechanic before pilot training. He had left his wife and four children behind in Manila and they were later interned by the Japanese.

When Davies and his men finally found them, their A-24s were in deplorable condition. Some of the most critical parts had not been shipped, particularly about half the trigger motors required to operate the forward-firing machine guns. General Brereton recorded in his diary that the Army was aware of the missing trigger motors and sent them out on a couple of B-17s, but the bombers were halted in Hawaii.

It turned out that some, if not all, of the 52 planes had originally been built for the Navy. Their bomb shackles were not fitted to carry Army bombs. It was evidently at this point that Gunn became a part of Davies’ team. His mechanical expertise and former Navy background were put to work improvising to make parts function until the proper ones could be delivered. According to Davies, Gunn designed the needed parts and took them to local machine and electrical shops to have them manufactured.

Due to the condition of the planes, the planned reinforcement of the Philippines never took place. The FEAF headquarters arrived in Australia a couple of days after the men from the 27th and began trying to achieve some semblance of order. A few days after he arrived in Darwin, General Brereton moved his headquarters to Java since it was where the Allies expected the Japanese to strike next. Davies was placed in charge of a training section that included pilots who had come out of the Philippines as instructors to train P-40 and A-24 pilots.

New arrivals from the States had little experience beyond flight school. Due to the lack of qualified pilots, only one squadron, the 91st Bombardment Squadron, was manned in time to participate in the disastrous Java campaign. No gunners or mechanics had come from the Philippines, so men were picked from those showing up in Australia. The group started out at Amberly Field then moved to Archerfield, both near Brisbane, before moving northwestward to Batchelor Field near Darwin.

In mid-January, Lieutenant Gerald Keenan, in charge of the pursuit training program, requested some of the A-24s be made available to allow the newly arrived fighter pilots, few of whom had any flight time in high-performance aircraft, to gain some experience in a more powerful but lower performance plane before they started flying P-40s.

The accident rate among the new arrivals was atrocious. Why Keenan’s request was not granted is inexplicable. In his denial of the request to convert the squadron, Lt. Gen. George Brett, the senior U.S. officer in the theater, stated that he did not understand why the A-24s were being declared obsolescent. In reality, there was good reason for the declaration as the Banshees were hardly suitable for combat. They were not equipped with self-sealing fuel tanks, which meant that hits in the tanks would result in gasoline leaks that were likely to turn them into flaming coffins. While the P-40s were brand new, with zero time engines, the A-24s had been shipped with engines that were already in need of overhaul. Consequently, they consumed copious amounts of lubricating oil and were incapable of producing full combat power. They had no armor plate, and the gunners in the rear seats were mostly novices. The dive bomber pilots had started referring to them as “Blue Rock Clay Pigeons,” after the clay pigeons used in aearial gunnery practice.

In mid-February, several A-24s from the 91st Bombardment Squadron moved to Malang on Java. The first deployment consisted of only three airplanes that had just arrived the previous evening. They were led by Captain Edward Backus, an experienced pilot who had spent seven years flying with the airlines. He led the flight through rough weather and found the field at Timor, but the antiaircraft gunners opened up on them. Two of the planes were so badly damaged that they had to return to Darwin for repairs. Backus continued on to Java alone. Eventually, seven A-24s reached their new base at Malang.

On February 19, two A-24 crews made the first dive bombing attack ever attempted by Army pilots and the first with the SBD/A-24. Japanese forces had landed on Bali the day before. Several attacks had been made on Japanese ships by B-17s and LB-40s with little success. There was no bomb handling equipment for A-24s at Malang, and the bombs had to be loaded by hand, a slow process. When an air raid siren sounded, two pilots, Captain Harry Galusha and Lieutenant Julius Summers, whose planes had already been loaded, were told to take off and remain near the field until all was clear. Radio personnel on the airfield overheard the two pilots’ conversation.

“Shall we go over to Bali and take a look around?” asked Galusha. “You’re the one with a wife and kids—let’s go,” was the reply. As they neared the island under the concealment of clouds, they spotted a transport and destroyer and peeled off from 11,000 feet. They released their bombs at 3,000 feet, and both observed hits. Fortunately, they caught the Japanese off guard and received little flak and saw no fighters. They headed back to Malang and wondered how their mission without orders would be received. As it turned out, a PBY reported that both ships had been sunk, and nothing was ever said. In fact, they were both recommended for decorations, which were presented by General Brereton when he visited Malang just before the evacuation of Allied air power from Java. The sinking report turned out to be erroneous, but both ships did receive damage from the bombs.

The following day FEAF sent out what should probably be considered the first truly coordinated U.S. Army air attack of World War II. Until this time the dive bombers had only flown one attack mission, and it had not been ordered. The February 20 mission against the ships off of Bali was planned primarily as a dive bombing attack by the seven A-24s of the 91st Bombardment Squadron. Three LB-30s from the 11th Bombardment Squadron, 7th Bombardment Group would provide additional tonnage. Sixteen 17th Pursuit Squadron P-40s would escort the bombers. The mission got underway at 6:15 am, when the LB-30s took off from Jagjakarta and headed east toward Malang to join the A-24s and P-40s.

The fighters met the bombers over Malang. The formation proceeded toward Bali with the dive bombers at 12,000 feet, the LB-30s at 13,500, and the fighters at 14,000. Immediately after landing the Japanese had captured the airfield at Den Pasar and sent in fighters to protect the invasion fleet. As the American formation approached, an estimated 30 enemy Mitsubishi Zero fighters were scrambled. The Zeros were climbing as the A-24s rolled over into their dives, and the bomber pilots saw the P-40s screaming down to tear into them. Thanks to the fighters, the A-24 and LB-30 crews dropped their bombs unmolested by the Zeros, although antiaircraft fire claimed two of the dive bombers.

Lieutenant Richard Launder managed to safely ditch about eight miles from the occupied beaches. He and his gunner, Corporal I.W. Leninicka, made their way back to Malang on foot, by bicycle, and by boat. The dive-bombing attack was successful. The five A-24s that returned from the mission reported 10 hits on four ships. Launder reported two more on what he thought was a cruiser. The LB-30 crews also claimed three direct hits and one waterline hit on a ship that was reported as a cruiser. The P-40s shot down three Zeros and claimed another destroyed on the ground in a strafing attack on the airfield, but they lost four planes during the battle and a fifth cracked up on landing due to battle damage. That pilot survived. Two of the four pilots were rescued, but the other two were lost, including the 17th Pursuit Squadron commander.

By February 24, the Allied high command had realized the situation in Java was hopeless and had decided to begin withdrawing. The senior U.S. commanders in Asia at the time, Generals Brett and Brereton, both believed the best route to attack Japan was through China from India. At the same time, Japanese troops had captured Rabaul in the northern Solomons and were threatening Australia. In the end, Brett would go to Australia and Brereton to India. On that day, Brereton dissolved his FEAF headquarters and departed on an LB-30 for Calcutta. He took with him several of the more competent combat leaders, including Captain Grant Mahony, who had just been given command of the 17th Pursuit, and the 91st Bombardment Squadron Commander, Major Edward Backus. Captain Harry Galusha, who had returned from the unauthorized mission to Bali expecting to be disciplined, was given command of the squadron.

On February 27, three A-24s attacked a Japanese convoy off Java. The naval Battle of the Java Sea erupted beneath them as they proceeded toward the enemy. The three Banshees were all that remained of 11 that had been sent out from Darwin several days before. A fourth was still intact at Malang but had hydraulic problems and could not go on the mission. The squadron commander, Captain Galusha, looked for an aircraft carrier but could not see one, so he elected to go for the transports instead. The pilots returned to report that they had sunk three Japanese transports, but their escorting P-40s only saw one go down.

When they got back to Malang, the pilots found the airfield nearly deserted. Only their own maintenance men and two officers from the 19th Bombardment Group remained. They were supposed to fly their three airplanes out, but one had been shot up so badly that it could not be flown. The next morning, the two A-24s flew across the mountains to Jogjakarta while the rest of the squadron went by ground transport. Fifteen Banshees started for Java. Seven actually got into combat. Eleven of the 15 returned to Darwin.

After the retreat from Java, Davies, promoted to lieutenant colonel, remained at Batchelor Field with the group, which had 29 operational A-24s. About half the shipment of 52 was given to the Royal Australian Air Force. On February 25, while FEAF was engaged in operations in Java, the 3rd Bombardment Group arrived at Brisbane. Although the group had operated Douglas A-20s at its previous station at Hunter Field in Savannah, for some reason its planes were not shipped to Australia. The 3rd found itself grounded. For a month the 3rd had no airplanes and no mission.

On March 25, 1942, the 27th Bombardment Group appeared at Charter Towers Field, where the 3rd had been sent after it arrived in Brisbane. The 27th consisted of 42 officers, 62 enlisted men, and the 29 A-24s just moved back from the Northwest Territories. The move was the result of a special order from General Brett in Australia, assigning the men and planes of the 27th to the recently arrived 3rd Bombardment Group.

Combining the two groups was met with some temporary resentment on the part of the men of the 3rd. The orders reassigned Colonel Davies to command of the 3rd. Its former commander, Lieutenant James Strickland, was reduced to executive officer but promoted to captain. Davies did not take official command of the group until April 2. During the interim something happened that changed the fortunes of the group and breathed new life into the U.S. bombardment role in the Southwest Pacific.

Gunn had been promoted to major and was the commanding officer of the Far East Air Force Air Transport Command. Shortly after the 27th arrived at Charter Towers, Gunn was on a flight to Melbourne when he happened to spot a ramp full of twin-engine bombers. When he got on the ground, he found a young sergeant named Jack Evans, who told him that the airplanes, which turned out to be North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers, had recently arrived from the States and had been intended for the Netherlands East Indies Air Force (NEIAF), which had been practically destroyed on Sumatra and Java.

Since the NEIAF was virtually nonexistent, the airplanes were sitting idle. Gunn decided immediately to get them for the 27th Group. He jumped in his Beechcraft and headed north. During the flight he hatched a plan to confiscate the bombers. When he reached Charters Towers, he went to Jim Davies’s office and told him about the B-25s.

Davies convinced Brig. Gen. Eugene Eubank of V Bomber Command to write an order authorizing him to go to Melbourne to pick up “the group’s” B-25s. The next day Davies took a group of pilots, including Gunn, to Melbourne on the morning mail plane. They returned to Charters Towers with the B-25s. Sergeant Evans returned with them and became Pappy Gunn’s sidekick.

On April 2, Davies assumed command of the 3rd Bombardment Group. He immediately summoned the officers to his headquarters and made some reassignments. Captain Floyd Rogers was given command of the 8th Bombardment Squadron, which would be equipped with A-24s. Captain Herman Lowery was given the 13th Bombardment Squadron, which would receive the purloined B-25s being made combat-ready by Pappy Gunn. Gunn was also affected by the changes; he was relieved of his position as commander of the 21st Transport Squadron and the Air Transport Command and reassigned to the 3rd Group as a maintenance officer. Captain Ron Hubbard took command of the 90th Bombardment Squadron, which also would receive B-25s, while Lieutenant Don Hall retained command of the 89th, destined to equip with A-20s once they arrived in Australia.

Captain Floyd Rogers was not present at the meeting with Colonel Davies. On the morning of March 31, he had been ordered to take his squadron north to Port Moresby, New Guinea, where Royal Australian Air Force No. 75 Squadron had recently arrived with P-40s to defend against Japanese attack.

On the afternoon of March 31, Rogers led 14 A-24s off the strip at Charters Towers and headed north for New Guinea, where they would be the first American combat aircraft to operate from the forward facilities. By the time the formation reached Jackson Field, they were down to eight planes, and two of those collided on the ground after landing and had to be repaired. Four had turned back due to excessive oil consumption by their worn-out engines, and two more mired in the mud at their refueling stop.

Shortly after their arrival, Rogers came down with dengue fever and was sent back to Australia. Lieutenant Bob Ruegg took his place at the head of the squadron. On April 1, Ruegg led five dive bombers on the first mission against Lae—a sixth plane blew a gasket on takeoff and aborted.

The fighters went ahead of the A-24s and reported that Lae was socked in, so they diverted to hit Salamaua instead. They dropped five bombs on the airstrip and then strafed the buildings and some vehicles.

The following morning, Ruegg led another strike against Lae. Two more A-24s had come up from Australia, and the sixth airplane had been repaired so he had eight in the formation. This time the airfield at Lae was in the clear, and they dropped their bombs on either side of the runway. The escorting fighters reported that two planes and two buildings were destroyed by the exploding 500-pound bombs.

Fighters from the Tainan Wing, one of the most famous of the Japanese air wings, intercepted the formation. Three American fighters were shot down along with one A-24 flown by Lieutenant Henry Schwartz. A second A-24 suffered major damage, but the pilot, Lieutenant Jim Holcomb, managed to land safely at Moresby. Ruegg was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for operations from Port Moresby. The wording on the citation attributes his missions during that period to B-25s. The planes were actually A-24s.

A few days after the 8th Bomb Squadron began operating out of Port Moresby, the first B-25s arrived. They were sent on a mission against the airfield at Gasmata on New Britain in conjunction with a raid on Rabaul by B-17s and B-26s. The Gasmata raid was successful, and the following day Davies, Gunn, and Lieutenant James MacAfee were called to Melbourne. Expecting to be arrested for the theft of the Dutch B-25s, Davies and Gunn were surprised to learn that they were going to Mindanao. The mission, which became known as the Royce Raid because its commander was Brig. Gen. Ralph Royce, was to bring relief to the men fighting on Bataan and allow a supply convoy to get through. Unfortunately, the commander on Bataan surrendered on April 9, the day before the mission departed, and Japanese forces captured Cebu the following day. Consequently, the mission turned into an attack on the Cebu waterfront and on the port at Davao.

The 8th Bomb Squadron remained in New Guinea through April and flew missions as often as possible against Lae and Salamaua. Because the A-24s were so slow, they suffered heavy losses at the hands of the Tainan Wing pilots. By the end of April, only 14 operational A-24s remained. Fortunately, more Dutch B-25s became available, and the 3rd Group depended on them until they started receiving airplanes from the States. The group suffered a devastating blow on May 14, when six B-25s from the 13th Bombardment Squadron were intercepted by Zeros. All but one of the B-25s and their crews were lost, including the squadron commander, Captain Herman Lowery.

By early July, the 8th had equipped with A-20s. When a Japanese invasion force was sighted off Buna, it was ordered to Moresby with 14 A-20s and 12 B-25s. On the afternoon of July 21, General Brett ordered all available aircraft out on missions against the enemy landing force at Buna. Twelve A-24s under Captain Floyd Rogers led the attack. As they and their escorting P-39s—led by Captain Tommy Lynch—approached Buna, they were intercepted by two dozen Zeros, and a dogfight broke out. Two P-39s and two A-24s were lost; the Japanese fighters disrupted the A-24 attack, and only a few hits were scored on a couple of supply dumps and two barges. A second attack the following day did not include A-24s.

July 29 was a disastrous day for the 8th Bombardment Squadron and the end of the combat career of the A-24 in the Southwest Pacific. Two days earlier Allied intelligence picked up word that a Japanese convoy had left Rabaul headed for Buna with reinforcements and supplies. At dawn, Captain Rogers and seven A-24 crews prepared their airplanes for a dive bombing attack against the ships. Colonel Davies briefed Rogers to concentrate his attack on the Japanese transports. The B-25s would follow up with an attack on the remaining supply ships.

At 7 am, the seven A-24s took off. They were joined a half hour later over the mountains by 12 P-39s led by Captain Lynch. The formation ran into clouds as they neared the target area, and Rogers radioed Lynch that he was going to have to drop beneath them to acquire the target. Lynch replied that he would bring six of his P-39s down to stay with them while the other five stayed at altitude to provide top cover. During the descent the fighters lost contact with the dive bombers; when the A-24s broke out, their escort was nowhere to be seen.

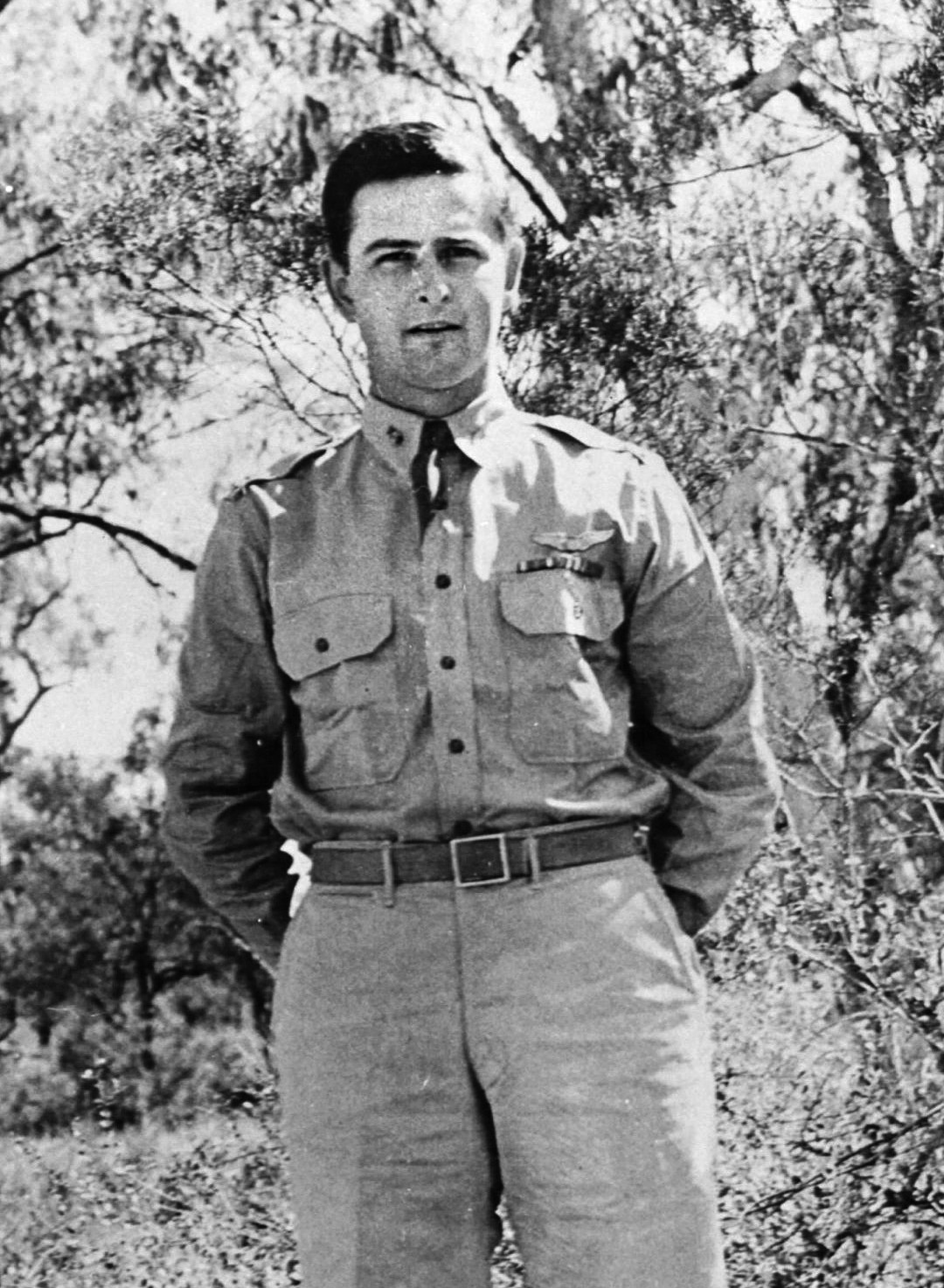

An umbrella of two dozen Zeros—the feared Tainan Wing—was in place over the convoy. Famed Japanese ace Saburo Sakai was part of the enemy force. Sakai had also been on the mission that accounted for the five B-25s two months before. Now he and his comrades were presented with what he later referred to as “a sumptuous feast” when they spotted the unescorted dive bombers. Within minutes Sakai and his squadron mates downed six of the seven unfortunate A-24s, including Captain Rogers’. Only one crew escaped the slaughter, and the pilot, Lieutenant Raymond Wilkins, would spend the next year avenging his lost comrades. The North Carolina native rose to command the 8th Bomb Squadron and was promoted to the rank of major. He had arrived in Australia in December 1941, in the same convoy that brought the 27th’s A-24s, and had joined the group immediately when Major Davies was rounding up pilots.

On November 2, 1943, Major Wilkins led his 8th Bombardment Squadron into Rabaul’s Simpson Harbor in one of the most devastating attacks of the war. His B-25 was hit by flak as he was making a run on a destroyer that was protecting the entrance to the harbor. In spite of damage to his airplane, Wilkins continued the attack and hit the destroyer with two bombs, which blew it apart. More fire struck the bomber as Wilkins pulled up after the bomb run, and his B-25 went into the sea. Wilkins was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor for his actions that day. At the time of his death, he was the longest serving U.S. pilot in the Pacific.

The loss of the six A-24s and their crews at Buna caused Colonel Davies to remove the remaining Banshees from combat. Even before the disastrous mission, Davies and the other former 27th Group pilots had come to the conclusion that they were dangerous. The Blue Rock Clay Pigeon moniker was an indication of how they felt about the dive bombers. They had been used in spite of their drawbacks for the simple reason that until B-25s and A-20s began arriving they were the only light or medium bombers available. Although they were just as fast as the B-17s that were operating in the theater at the time, the single .30-caliber machine gun in the rear cockpit offered minimal defense against fighter attack, and then only from the rear. The two forward-firing .50-caliber machine guns mounted in front of the pilot were of little use against fighters, especially while they were still carrying a load of bombs.

The removal of the A-24 from combat operations after the July 29 losses brought the story of the 27th Bombardment Group to a close, although many of the pilots would go on to make history with the 3rd Group, which was commonly known as the 3rd Attack Group.

On May 4, 1942, the 27th Group officially returned to Hunter Field, although the move was strictly paperwork since its personnel in Australia were still fighting with the 3rd Group. A new 27th Bombardment Group was formed at Hunter, this time with A-20s. In November 1942, it moved to North Africa, where it converted to the North American A-36, the dive bomber version of the soon-to-be-famous North American P-51 Mustang, and became part of General Jimmy Doolittle’s Twelfth Air Force. In January 1944, the group converted to P-40s and became a fighter group. Six months later the 27th transitioned into Republic P-47 Thunderbolts, which it operated until the end of the war.

The officers and men of the 27th who transferred to the 3rd Bombardment Group, including those who joined the group in Australia, were known for their aggressiveness. Some, such as Captain Herman Lowery, were lost in combat. Others died in aircraft accidents. At the end of July 1942, Maj. Gen. George C. Kenney arrived in Australia to take the position of chief of staff for air on MacArthur’s staff. Kenney was an expert on attack aviation and had previously commanded the 3rd Attack Group. The group became, perhaps, his favorite. But Kenney also realized that the men who had fought in the Philippines and Java were worn out, both physically and emotionally. In August, Colonel Davies wrote a letter to Kenney pointing out how the 27th veterans had fought courageously since the beginning of the war and should be sent home.

When General Arnold came to Australia in September, Kenney brought up the subject of the men who had been in the war since the beginning and recommended that they be replaced as soon as possible. Arnold agreed and told Kenney that he could use the veterans in training units back in the States. In October, 18 officers and two enlisted men who had been part of the 27th left Australia in a B-24 transport bound for the United States.

Just before the 27th veterans left for the United States, they were shocked to learn that a Filipino sailboat had arrived in Australia carrying two men, one of whom was Lieutenant Damon “Rocky” Gause, who had been with the 17th Bombardment Squadron. Gause had fought on Bataan but refused to surrender and swam the two miles through shark-infested waters to the island of Corregidor. When Corregidor surrendered, Gause again refused to surrender and managed to make his way to the mainland, where he was hidden for two months by friendly Filipinos.

Gause met up with an infantry officer, Captain William Osborne, who had managed to escape from Bataan and was also being hidden. They purchased a motorized sailboat from some Filipinos and set sail for Australia after first stocking up with supplies from a dump that was being guarded by a single unfortunate Japanese soldier. After a 3,200-mile journey that took them through the Southern Philippines, past Borneo, the Celebes, and Java they finally landed in northern Australia. After their arrival, they were flown to Brisbane, where they reported to General MacArthur.

Still wearing the same ragged and filthy clothes they had on when they landed and barefoot, they walked into the general’s office, saluted, and said, “Lieutenant Gause reporting from Corregidor.” Gause, who was killed later in Europe where he flew fighters, said that MacArthur’s words were, “I’ll be damned.”

Author Sam McGowan is a pilot and veteran of the Vietnam War. He resides in Missouri City, Texas.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments