By John Wukovits

“They’re machine gunning! They’re strafing the hospital! The beasts! The slimy beasts!”

“Pearl Harbor! Most of us didn’t know what it was, let alone where it was.”

“We’re still here—we’ll always be here— come and get it.”

Those words about and to the Japanese foe, emotional and stirring as they are, came not from any World War II American politician, political commentator, or soldier. They originated instead from Hollywood, the dream factory, the sunshine center of film that entertained audiences with the dancing of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, the comedy of Charlie Chaplin and the Three Stooges, and the beauty and grace of Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh.

While they may have, in some cases, overstated the concerns or served as examples of blatant stereotyping and bigotry, they accurately summed up the public’s mood in 1942 and 1943 and reflected the varying responses to events as they unfolded in the Pacific. Where the public saw sinister spies as orchestrating Japan’s initial onslaught, Hollywood made movies in which Humphrey Bogart bested secret agents. When the Japanese military juggernaut backed outnumbered American soldiers in the Philippines into near hopeless predicaments, Hollywood sent film heartthrob Robert Taylor into the fray, confounding the enemy with words and bullets as they charged his machine gun.

In the course of researching the Pacific War over a lifetime, I have amassed a collection of movies about the war that were released during the war years. Examples would be 1942’s Wake Island, a film produced about the gallant Marine defense of a tiny Pacific island, or 1944’s Since You Went Away, a film about life on the home front during the war. A collection that began with Guadalcanal Diary has grown in numbers to more than 40.

The movies I select to watch change from year to year, but a small number inevitably make it to my DVD player, appearing year after year without interruption. Most, I find, are films made during 1942-1943 or about events from those years, the desperate months when ill-prepared American forces tried to halt the Japanese military and regain momentum for the long struggle that in 1942 was still in doubt.

The immediacy of these films never fails to impress me. Through watching their actions and listening to their words, a viewer more than 60 years later learns how the nation felt during those desperate days. One senses the anger and the disillusionment directed at the government for being caught by surprise, the hatred and bigotry then common toward the Japanese, the defiance of a nation hurt by the death and desolation of Pearl Harbor, and the shattering of innocence as a nation comes of age in the world.

These films may be divided into five major categories—espionage and treachery, last stands, a glimpse of the enemy, hitting back, and the home front. Though by no means a scientific or complete survey of all World War II films produced during the war, these offer a snapshot of a country at war in 1942-1943, an image frozen in time.

It was no surprise that President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the master of politics and persuasion, quickly turned to Hollywood in Pearl Harbor’s aftermath. He understood that few vehicles in American life reached so wide an audience or so profoundly affected those it touched. What better way to convey to the public the government’s messages about war, the enemy, and home front restrictions than to utilize the local theater, where each week men, women, and children gathered to cheer their personal heroes or ogle luscious starlets?

“The American motion picture is one of our most effective mediums in informing and entertaining our citizens,” Roosevelt stated in December 1941. Few could disagree. In 1940, 80 million people, representing two-thirds of the population, headed to the shows. More than 400 reporters, including one from the Vatican, operated from offices in the California film community, where they covered the fads and foibles of Tyrone Power and James Cagney, Paulette Goddard and Greta Garbo. Only Washington, D.C., and New York City boasted a larger press presence.

Film producers made the new war a part of 72 films that appeared between December 1941 and the following fall, from the sublime Mrs. Miniver and Wake Island to those bordering on the ridiculous, such as Tarzan battling Nazi agents who parachuted into his jungle domain. The Office of War Information (OWI), charged with overseeing propaganda issues, hoped Hollywood would simultaneously entertain and inform its audiences, inserting valuable messages almost surreptitiously between the laughter and joviality. As OWI director Elmer Davis stated, “The easiest way to inject a propaganda idea into most people’s minds is to let it go in through the medium of an entertainment picture when they do not realize that they are being propagandized.”

The OWI issued a manual informing Hollywood studios how to aid the war effort, sent officials to confer with studio bigwigs, and reviewed screenplays for positive messages. The sacrifices asked of the home front, for instance, might be included in a film, but the OWI wanted the movie to portray men and women as willingly accepting rationing and shortages, smiles adorning their faces rather than frowns. The OWI suggested that screen writers and producers ask themselves seven questions about the film, including whether the picture would help win the war and if it would truthfully inform their audiences. Most studios gave at least lip service to the seven questions, knowing that blatantly ignoring a government request could sever the assistance the United States military handed filmmakers, but a perusal of films shows flagrant disregard for some, especially the notion of truthfully portraying issues.

Rather than mold public opinion, right out of the gate Hollywood reinforced existing home front fears and bigotry by producing films that focused on Japanese treachery, trickery, and espionage. According to these films, Japanese agents moled into American society in an attempt to stab in the back the United States, a charitable nation that had willingly sent steel and other products across the ocean. Rather than being grateful recipients, the Japanese instead proved to be that “yellow peril” that had long been feared, a people so inherently different from American citizens that no bridge could span the chasm. Hollywood had no trouble individualizing the German foe, but all Japanese were the same, automatons cut from similar cloth.

“In Europe we felt that our enemies, horrible and deadly as they were, were still people,” wrote that most venerable and beloved war correspondent, Ernie Pyle. “But out here [the Pacific] I soon gathered that the Japanese were looked upon as something subhuman or repulsive, the way some people feel about cockroaches or mice.”

During the war’s first year, more than 20 films dealt with espionage and sabotage. While similar treatments existed concerning the German threat, films targeting the Japanese menace rarely included humor as part of their portrayal. Two 1942 films involving Hollywood superstar Humphrey Bogart illustrated the diverse ways Hollywood painted the Germans and Japanese. Humor buoyed every scene in All Through the Night, a light-hearted thriller involving Bogart and his Runyonesque gang (including among its number a very young Jackie Gleason) pursuing Nazi agents (including Peter Lorre) because, in part, they murdered the baker who made Bogart’s favorite cheesecake. Bumbling thugs smacked each other around like the Three Stooges, while Bogart mimicked the Nazi salute during a meeting of infiltrators by repeatedly thrusting his arm forward, each time forcing a cessation in the proceedings as every German present stopped to follow suit. In the end, Bogart snared his man and foiled the Nazi plot to blow up a cruiser in New York harbor.

Bogart turned deadly serious in his second vehicle that year, a film involving Japanese agents attempting to dynamite the Panama Canal. Unlike All Through the Night, the September 1942 movie Across the Pacific offered neither jokes nor clumsy spies. Directed by John Huston and starring Mary Astor and Sydney Greenstreet, the movie pits a supposedly disgraced Army officer played by Bogart against nefarious enemy agents led by Greenstreet, intent on destroying the Panama Canal locks. Bogart steams for the canal, foils the plot, and returns a hero.

The February 1943 film Air Force, starring John Garfield, reinforced the stab-in-the-back theory. Filmed with the cooperation of the Army Air Corps and supposedly based on actual incidents described in official military files, the movie follows the journey of a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress as it wings its way from San Francisco to Pearl Harbor on December 6. Not surprisingly, the crew finds itself in the midst of the December attack over Oahu. After a hasty refueling, they proceed to Wake Island and the Philippines. Time magazine labeled the film “a superbly thrilling show,” while the New York Times claimed the movie would leave audiences “limp and triumphant at the end of its two-hour ordeal.”

The New York Times was also correct in adding that the movie exaggerated certain features, but every product released at that time could be accused of stretching the truth. That is, after all, the basis of propaganda, and Air Force leaned heavily on half-truths and stereotypes. One of the characters claimed that every defeat absorbed in the Pacific was caused by sinister fifth columnists working from within the system, and the film even shows the bomber being shot at by Japanese residents of Oahu as it approached Pearl Harbor. Later, subversive elements in the Philippines ignite brush fires to guide Japanese bombers to their targets, and a Japanese pilot machine guns a helpless American flier as he parachutes from his damaged aircraft.

The movie encapsulates the nation’s response to real and supposed treachery when a character admonishes the Japanese while attempting to boost audience morale. “Listen, any buck-toothed little runt can walk up behind Joe Louis and knock him cold with a baseball bat—but a clean man don’t do it. Your Uncle Sammy is civilized: He says, ‘Look out, you sneaks, we’re gonna hit above the belt and knock the daylights out of you!’”

That message was continued by a collection of films that Richard Lingeman calls the “last-stand” pictures, films that conveyed to the enemy that while they may have momentarily knocked the nation’s military on its heels, they had in actuality only poked a hornet’s nest with a stick. These movies shifted the focus from defeat to the gallant military endeavor to delay the Japanese so the United States military and industrial machine would have sufficient time to field a response that would inevitably end in Japan’s defeat. They highlighted men and women from every part of the land, boys from Kansas and girls from Brooklyn, who defiantly battled a vicious foe. Never letting a good opportunity pass by, the principals delivered rousing messages to the nation and the enemy.

No one less than Clark Gable starts the ball rolling in 1942’s Somewhere I’ll Find You, a delightful montage of intrigue, suspense, and romance featuring powerful performances from Gable and the object of his lust, Lana Turner, equally impressive as a female reporter. After watching second-rate but fun movies like Secret Agent of Japan, a viewer learns why Gable and Turner amassed such reputations. Their talents soar beyond those of their contemporaries as they steal every scene.

The film opens with newspaper reporter Gable returning from assignment in Europe, where he observed firsthand Hitler’s march to power against enfeebled democracies more bent on appeasement than action. Gable immediately heads to his newspaper’s building, where he bursts into the publisher’s office and delivers a stern lecture illustrating how the isolationist sentiment that gripped much of the nation in the late 1930s opened the door for Hitler’s Nazi tyranny.

Gable eventually winds up in the Philippines, where he concludes the movie with a stirring account of the sacrifices made by both American and Filipino forces battling on Bataan. Firing words in staccato fashion as he dictates a story for his publisher in New York, he talks of “brown men and white men fighting together and when they bled their blood was the same color.”

The epitome of the “last-stand” films arrived with one of Hollywood’s first endeavors after Pearl Harbor, the September 1942 movie Wake Island. Supposedly based on actual Marine accounts and starring Hollywood heavyweights Brian Donlevy, Robert Preston, William Bendix, and Macdonald Carey, the movie portrayed the stout Marine defense of Wake Island, a tiny outpost in the central Pacific. While the rest of the Pacific quickly succumbed to the Japanese military, and with the pride of the U.S. Navy lying on Pearl Harbor’s bottom, one beacon lit the gloom—the glorious two-week defense of Wake Island, an action that momentarily halted the Japanese juggernaut while boosting a tattered home front morale.

Today we laugh at how quickly television cranks out a movie-of-the-week based on current events, but few could match the speed with which Hollywood approached the fighting at Wake Island. A script begun before the Wake garrison surrendered in late December 1941 included the usual wartime stereotypes and exaggerated comments.

A Japanese diplomat, representative of envoy Saburo Kurusu, who stopped at Wake Island in November on his way from Tokyo to Washington, D.C., sports buck teeth and thick spectacles, while Japanese soldiers during the December battle enter a hospital to bayonet helpless wounded. Donlevy, in the role of the Marine commander, comforts a compatriot whose wife had been killed in the Pearl Harbor attack by asserting in the less than stirring words, “We’ve got to destroy destruction. That’s our job,” and later borrows from a glorious page in American history when he admonishes his battery commander, “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.”

The movie’s producers pulled out all the stops to depict a once-torn nation now united by the dastardly December 7 attack. Before war erupted the two groups laboring on the island, the Marine garrison and the large contingent of civilian construction workers sent to build Wake’s defenses, treated each other with disdain. The construction boss argued with the Marine commander over areas of authority, and fights erupted between Marine privates and construction workers. The Japanese assault instantly united both groups, however, with civilians manning guns alongside Marines.

As the film’s end nears, the Marine commander played by Brian Donlevy stands toe-to-toe with the construction boss, played by Albert Dekker, blasting away with their machine gun while Japanese soldiers surround their position. Adhering to the then common dictate to avoid showing the death of an American while fighting to the last, the movie ends with an explosion that kicks up a large cloud of dust, and a narrator’s voice proclaiming as the Marine Corps Hymn plays in the background, “This is not the end. There are other Leathernecks, other fighting Americans, 140 million of them, whose blood and sweat and fury will exact a just and terrible vengeance.”

The film became an instant sensation in the United States, earning a spot alongside Mrs. Miniver as audience favorites for 1942. Newsweek stated that it “is Hollywood’s first intelligent, honest, and completely successful attempt to dramatize the deeds of an American force on a fighting front.”

Bosley Crowther, the film critic for the New York Times, attended a screening of the movie with 2,000 Marines at Quantico, Virginia, and watched as the Marines wildly cheered the film’s heroics. He wrote, “Here is a film which should surely bring a surge of pride to every patriot’s breast” and stated the movie was “about heroes who do not pose as such.”

Newsweek was only partly correct in calling the film honest, as much had to be based upon supposition. In researching my book about the battle, I interviewed many of the Wake Island Marines. To a man they agreed that while the film proved to be good entertainment the only accurate aspect was that there was an island and men fought on it.

On the other hand, Crowther aptly concluded that the Wake Island battlers were heroes without seeking recognition. Again, in the course of my interviewing, each aged Marine in recounting his actions scoffed at the notion that he was a hero. “I was just doing what I was supposed to do,” they affirmed in a powerfully understated manner.

Despite any shortcomings, the film is good fun and received four Academy Award nominations.

The early 1942 combat in the Philippines, which featured desperate fighting from hopelessly outnumbered forces against a well-oiled Japanese military, provided a fertile backdrop for Hollywood’s last-stand films. A smaller offering comes with The Eve of St. Mark, a film starring Vincent Price and Harry Morgan of M*A*S*H fame. Based on a 1942 screenplay by Maxwell Anderson about a group of American soldiers trapped in a near hopeless position in the Philippines, the film focuses on whether the soldiers should attempt to evacuate their position or remain and fight to the death.

Never a threat to vie for Oscar nominations, the film delivers a steady diet of astounding dialogue. “I’m drafted for a year,” one young soldier tells his girlfriend before leaving the country, then displays a shocking mathematical deficiency by adding, “but I’m afraid it’s going to be a year of several summers and half a dozen winters and heaven only knows how many lonely nights.” Vincent Price quotes Shelley and Shakespeare, and compares himself to a “young Alexander [the Great] dying” before succumbing to malaria.

When one soldier wonders why they should sacrifice themselves for a country that failed to heed the signs of imminent hostilities and prepare for war, he hears the answer that powers the movie. “We’re not fighting Japs,” responds his buddy. “We’re fighting so that 1950 kids won’t have to steal potatoes from boxcars” like he and other youths had to do during the Depression. He convinces the group to hold their positions and delay the enemy as long as possible.

Bataan, released in June 1943, is a far superior movie dealing with American soldiers mounting a last stand in the Philippines, and one of the best war films to emerge from World War II. The film gathered a luminous collection of actors to rival Across the Pacific, including Robert Taylor, George Murphy, Thomas Mitchell (not long after completing Gone with the Wind), Lloyd Nolan, Robert Walker, and a young Desi Arnaz. They comprise the 13 men of a platoon detailed to delay the Japanese long enough for other American units to retreat.

The director, Tay Garnett, deftly used the 13 characters to portray both a nation united as well as the grit that would carry the nation through to ultimate victory. He opens the film with a sequence popular among movies of the day, Japanese planes strafing Filipino children and bombing a hospital packed with wounded American soldiers. When one bandaged soldier tries to hobble from the hospital, a Japanese bomb dislodges a wooden frame that falls on the soldier and crushes him to death.

After that heavily propagandized sequence, Bataan provided one of the most beautifully depicted stories to emerge from the film industry. Unlike most other offerings, Bataan gives screen time to each of the 13 members of the doomed platoon, in that fashion providing background for each man, building empathy for the character, and making each soldier’s death more meaningful to audiences. In a clever move, practically every ethnic group in the nation is represented, including men from Spanish, Polish, and Italian backgrounds, a Jew and a Catholic, a grandfather-type played by Mitchell, a fresh-faced youth played by Walker who alternately thinks of mom and killing his first Japanese soldier, and in an impossibility for the segregated Army of the day, an African-American. In an intentional move to illustrate that the nation was being defended by the common citizen, not one of the 13 came from the professional ranks back home. They were the average Joes fighting for mom and dad, soda jerks and farmers dying for all that is good.

As the movie unfolds, the Japanese slowly approach the platoon’s position. One by one, the 13 die, always by an enemy purposely kept concealed until the film’s final sequence, when they camouflage themselves with tree branches for the last assault against the lone survivor, Robert Taylor, the platoon sergeant who dispensed wisdom and tough love to his men. “It don’t matter much where a man dies,” he tells Robert Walker as the crying youth struggles with his predicament, “as long as he dies for freedom.” In a message directed at theater audiences, as the enemy closes in on Taylor, who heroically fires his machine gun from a grave he had dug for himself, Taylor shouts at the Japanese, “We’re still here—we’ll always be here— come and get it.”

As in all last-stand movies, Taylor goes down fighting, but his death is not actually shown. He continues to fire his weapon, grinning madly as the Japanese draw near. The film, which touched audiences in 1943, still packs an emotional wallop more than 60 years later.

Surprisingly, the war years delivered some of the strongest leading roles for female actors, with Claudette Colbert starring in two major wartime vehicles and Greer Garson in the Oscar-winning Mrs. Miniver. The Philippine campaign offered two World War II films portraying the role of nurses with 1943’s So Proudly We Hail and Cry Havoc. The first, featuring Paulette Goddard, the stunning Veronica Lake, George Reeves (who later enjoyed television fame as Superman), and Sonny Tufts joining lead actress Claudette Colbert, entered theaters in September. Mirroring Bataan, the film immediately resorts to a stereotype with the Japanese bombing a hospital and a character raging, “They’re strafing the hospital! The beasts! The slimy beasts!”

Colbert’s character, nurse Lieutenant Janet Davidson, then takes center stage to blame pre-war isolationism for the military’s ill fortune in the war’s early going. She explains that one thing led to the U.S. retreat in the Philippines. “Because we have no quinine, and the things that go with quinine: big guns, and troops, and food, and a responsibility to the world we live in. Why? Because old men said we were impregnable between two oceans.” Colbert added, “Who should we have listened to—our President? Or those who smugly told us the smug things we wanted to believe in?”

The movie later graphically illustrates that a united population, willing to sacrifice, would lead to victory. Veronica Lake, mourning the death of her fiancé at Pearl Harbor, courageously sacrifices her life and kills a group of enemy soldiers by igniting a hand grenade as she supposedly surrenders to the Japanese. Colbert lends added heroism to the deed by telling the other nurses, and at the same time admonishing audiences, “It’s the people’s war because they have taken it over and are going to win it and end it with a purpose—to live like men with dignity, in freedom.”

Nurse Colbert validates Lake’s sacrifice, and the tragic loss of every American fighting man in the Philippines, with another strong message targeted at home audiences—the fighting forces in the Pacific sacrificed themselves to give the nation time to rebound from Pearl Harbor. Whereas Robert Taylor and his hardy platoon handed time to the country with their deaths in the Philippines, this time the women contribute. “We’ve become what they call a delaying action. We are saving time and I hope to God the people back home aren’t losing it for us.” She adds, “It’s our present. We’re giving them time.”

The powerful film ends with the voice of Colbert’s husband, whom she married during the siege of Corregidor shortly before he was killed in the fighting. In tender, loving words the future Superman, George Reeves, tells his bride to keep her chin up, do her duty, and that the war would result in precisely what they all sought, a bright future as symbolized by the farm he had purchased for her.

Though Colbert and most of the nurses eventually escape death when they are evacuated from the islands, the same is not true for 1943’s other film about nurses in the Philippines, Cry Havoc. The movie, a weaker imitation of Colbert’s stellar film, ends with the surrender of the nurses to a group of Japanese soldiers whose intent is all too clear, even if Hollywood in 1943 would never depict it: rape and death.

Though the New York Herald Tribune praised the nurses’ heroism, which “has made our enemies change their opinion about this being a ‘soft’ nation,” most critics condemned the vehicle for relying too much on sensationalism. Captain Florence MacDonald, who commanded the Army nurses in the Philippines the film supposedly honors, wrote a letter to the playwright objecting to what she viewed as horrendous exaggerations. “You have managed to include horror, war, birth, death, destruction, horror, Lesbianism, insanity, hysteria, horror, smut, murder, spies, sex, horror, and even a little nobility.” She then added, “It should bring wonderful box office.”

In the early years of the war Hollywood delivered a handful of films examining the Japanese foe, but most succumbed to the temptation offered by other wartime products. Stereotype and simplicity of message overruled any serious study of the Japanese. In 1942, Little Tokyo, U.S.A. centered around the West Coast evacuation of Japanese Americans, not surprisingly crafting a pro-evacuation stance. The movie opens with another direct slap at prewar isolationism, blaming it for all the woes that then beset the country.

“For more than a decade,” the narrator states, “Japanese mass espionage was carried on in the United States and her territorial outposts while a complacent America literally slept at the switch. In the Philippines, in Hawaii, and on our own Pacific coast, there toiled a vast army of volunteer spies, steeped in the traditions of their homeland.” The narrator adds that the film “is presented as a reminder to a nation which until December 7, 1941, was lulled into a false sense of security by the mouthings of self-styled patriots whose beguiling theme was: it can’t happen here.”

The film depicts Preston Foster, fresh after foiling the Japanese in Secret Agent of Japan, as detective Mike Steele. Could a more American name have been selected? Steele investigates a series of crimes in Los Angeles. As the ever vigilant Steele digs deeper, he learns that the crimes are related. They were all committed by Japanese agents living in California who struck in coordination with the December 7 attack against Pearl Harbor. The clear message was that the nation could not trust any Japanese, even if they had long resided in the United States.

In one astounding scene, as Foster delivers a thorough thrashing to a dastardly Japanese American, he blurts, “That’s for Pearl Harbor, you slant-eyed….” The movie, hardly one of Hollywood’s most glorious efforts, concludes by justifying the removal of Japanese from the West Coast. “Unfortunately, in time of war, the loyal must suffer inconvenience with the disloyal.”

Although Edward Dmytryk’s 1943 Behind the Rising Sun featured horrendously made-up white actors portraying Japanese characters, Dmytryk was the first director to see a difference between the Japanese military and the Japanese people. He presented the Japanese government, then dominated by the military, as the evil, not the Japanese people themselves.

Co-star Tom Neal, as the Americanized son of a Japanese diplomat, returns to Japan in the 1930s, where the military gradually transforms him into a monster able to turn away as Japanese soldiers bayonet Chinese children. His father, played by J. Carrol Naish, witnesses his son’s shocking transformation and warns his friend, an American businessman named O’Hara, that he must leave Japan before it is too late.

In a symbolic scene, Robert Ryan squares off in a combination boxing-martial arts bout against a Japanese soldier, a jujitsu expert. When he and O’Hara learn that the expert has permission to kill Ryan, the American survives a savage beating to best the Japanese, thereby announcing that no matter how good the Japanese military thinks it is or what tools it applies, America will never be defeated.

As O’Hara leaves the country, Naish commits ritual suicide, explaining his reasoning for audiences around the world. “I do not die for the Emperor, a little man on a white horse. I die for the hope that the people of Japan can redeem themselves before the civilized world. But if that is not to be, then the Japan I know must die with me for one can’t build honor or dishonor. To whatever gods that are left in the world, destroy us as we have destroyed others. Destroy us before it is too late.”

After the initial flurry of movies dealing with the notions of betrayal from the Orient and epic last stands, Hollywood continued to reflect current events by turning to the “hitting back” genre. After losing the Philippines, Guam, and Wake Island, United States forces began striking back, first with the dramatic April 1942 Doolittle Raid on Tokyo, then by commencing the long drive toward Japan with the August 1942 landings on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

As always, the film industry followed in the wake of these events, producing major motion pictures on each action. The tone of this batch differed from its predecessors in that optimism seeped into the messages. No longer was a stunned country frantically holding on for dear life; it now inflicted blows on a surprised enemy, strikes that presaged eventual doom for the Japanese.

Unlike other movies mentioned in this article, films depicting the Doolittle Raid did not start production for a year after the event occurred. The War Department clamped a tight lid on information about the mission, other than stating that Doolittle had bombed Tokyo, both hoping to keep secret the news that the bombers launched from aircraft carriers and fearing that home front adulation over the event might provoke reprisals on eight captured Doolittle raiders. The War Department lifted the ban in 1943 after realizing that the enemy had quickly ascertained the origin of the bombers.

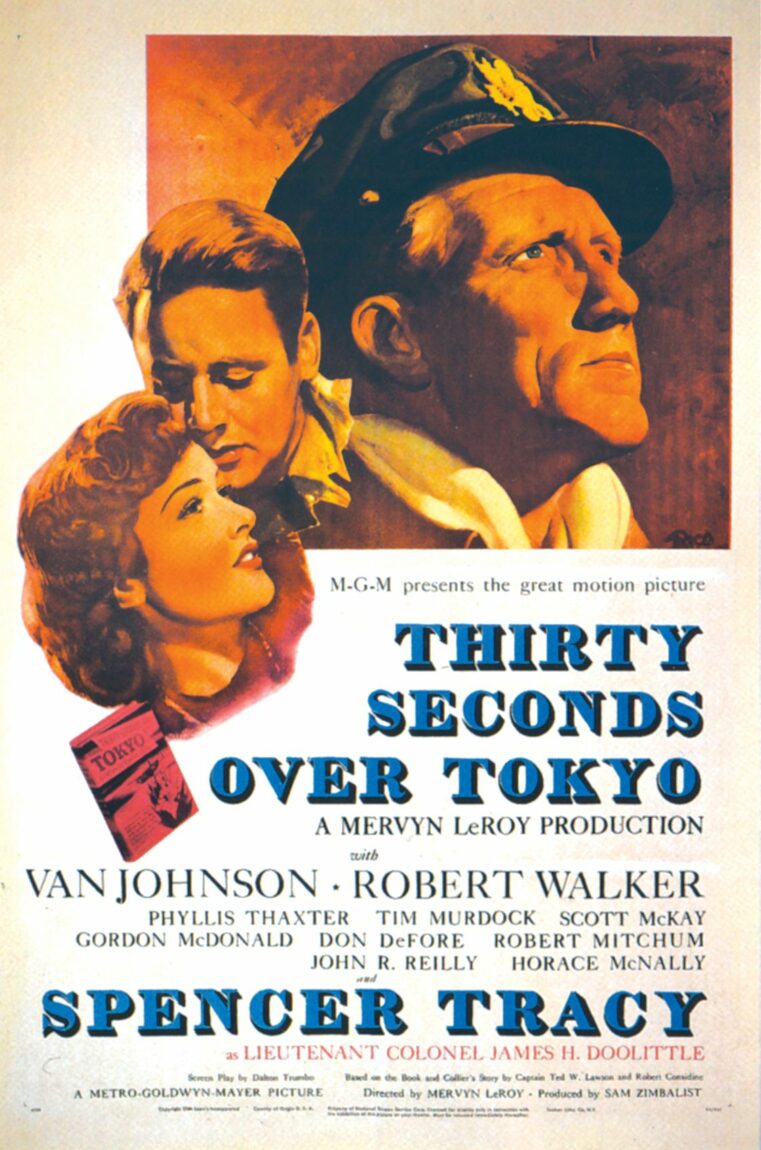

Doolittle’s bombing of Japan yielded two fine films. Newsweek called Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, released in November 1944 and starring Spencer Tracy as Colonel Doolittle, Robert Walker, Robert Mitchum, and Van Johnson “one of Hollywood’s finest war films to date.” The sentimental film, which used the American family to play on audience emotions, became one of the most popular films of its day.

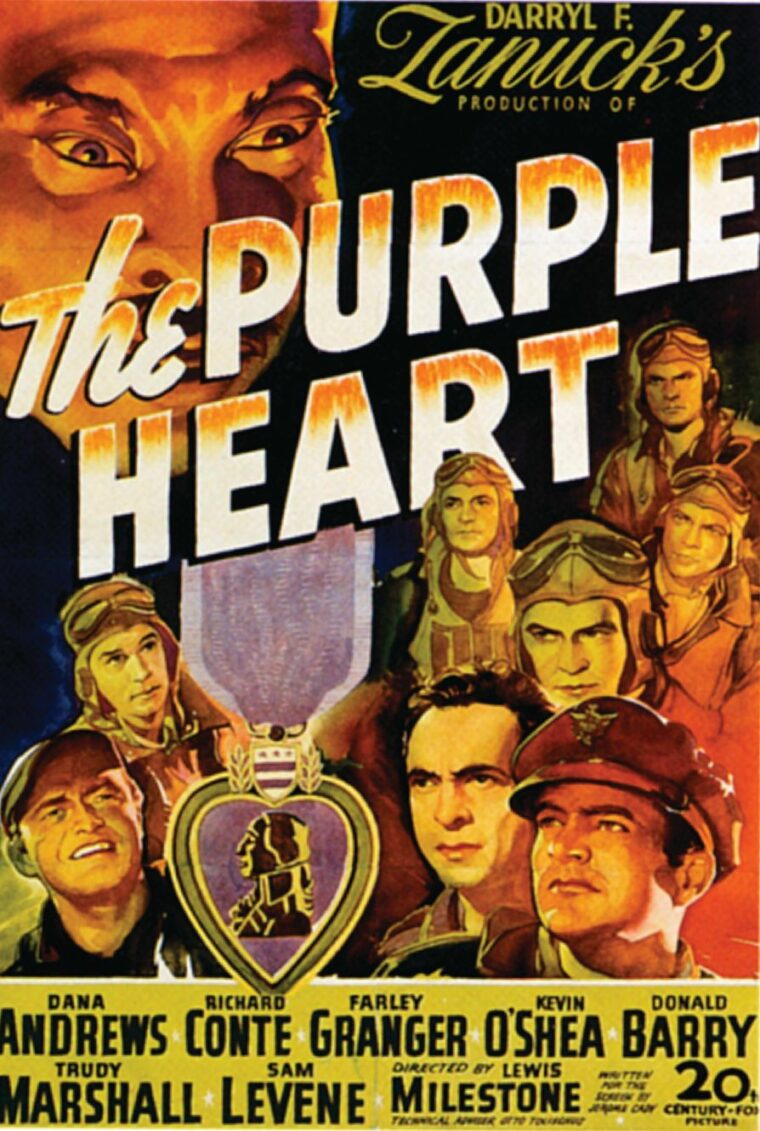

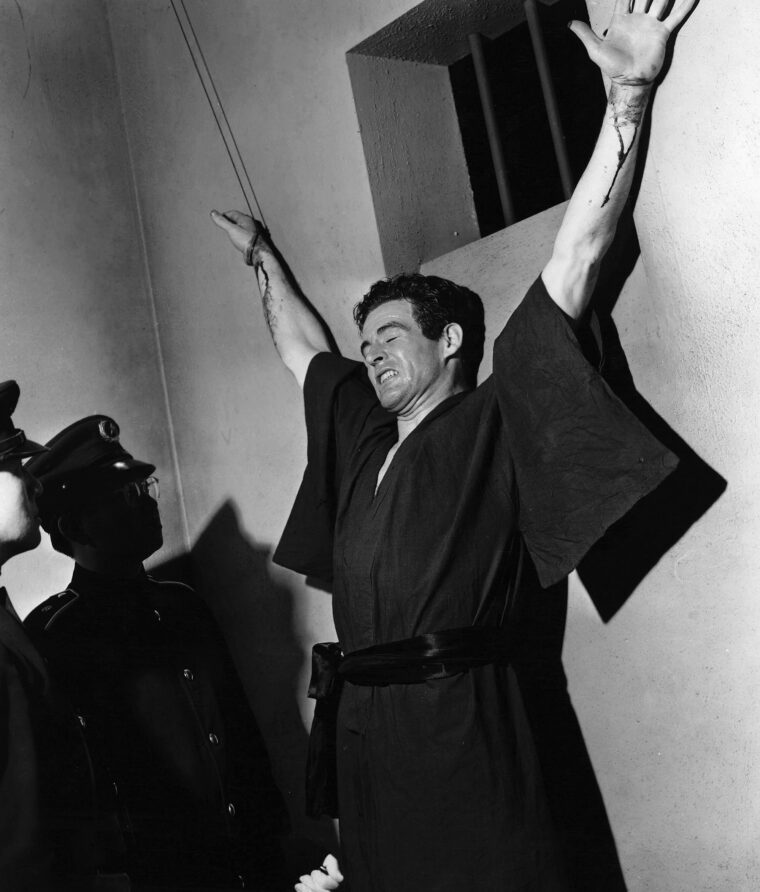

More wrenching was The Purple Heart, released in March 1944 and starring Dana Andrews and Richard Conte. While Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo focused on the raid itself, The Purple Heart concentrates on what happened to the eight captured Doolittle raiders. It begins in a Japanese courtroom, where the downed fliers are supposedly receiving a fair trial for their role in the mission. The director cleverly uses silhouettes on the wall to hint at the sadistic Japanese guards hovering about the American captives, willing to resort to torture at the slightest provocation, and employs a buck-toothed, maniacal character as the judge. Symbolizing the gallant contribution made by the Chinese, a son kills his father in court after his parent betrays the American fliers. As guards lead the son away to certain torture and death, Dana Andrews tells his captured raiders to stand up in the docket for a true American hero.

The film ends with Andrews, who knows he and the others are doomed to die, delivering a defiant warning to his captors similar to the one Clark Gable issued in Somewhere I’ll Find You. “You can kill us—all of us, or part of us,” Andrews vows. “But if you think that’s going to put the fear of God into the United States of America and stop them from sending other fliers to bomb you, you’re wrong—dead wrong. They’ll blacken your skies and burn your cities to the ground and make you get down on your knees and beg for mercy. This is your war. You wanted it. You asked for it. And now you’re going to get it, and it won’t be finished until your dirty little empire is wiped off the face of the earth!”

From the perspective of 60 plus years, one has to love the defiance of the 1940s. After receiving the expected guilty verdict, the American fliers proudly march from the courtroom, heads held high as they walk to their deaths.

Guadalcanal Diary, released in November 1943, remains one of the most gripping war movies of its day. Based on Richard Tregaskis’s best-selling book of the same name, written by a correspondent who accompanied Marine forces to the island, the film stars William Bendix and Lloyd Nolan, both resurrected after dying in Wake Island and Bataan, accompanying fellow Marines as they land on the Japanese-held jungle island. While the U.S. forces eventually triumph, the documentary-style movie does not shy from depicting the rigors these and, by implication, future American units face in wresting control of Pacific possessions from a gallant, but devious, enemy.

Bendix and others land on Guadalcanal, spouting wisecracks toward each other and challenges at the enemy. In one early scene Bendix shoots at what he assumes is a Japanese soldier perched in a tree, then explains, “I swore I could see his buck teeth.” Lloyd Nolan’s character shrugs off the island’s carnage with a simplistic notion that prevailed at the time. “It’s kill or be killed. Besides, they ain’t people.”

The film contains the usual collection of Marines. Bendix plays a character from Brooklyn who loves his baseball, a young Anthony Quinn adds the appropriate ethnic touch showing a united nation, Lloyd Nolan shines as the rough old Marine, and Richard Jaeckel symbolizes the innocence of a reluctant nation, fighting a war that was forced on it, by portraying a 17-year-old Marine who looks not a day older than 14.

The film moved audiences with its portrayal of the Goettge patrol, a small group of Marines hacked to death by the Japanese on the beaches while a terrified survivor watches 100 yards away. Viewers warmed to the cheerful frolicking of American youth, pulled from their peacetime pursuits to face a devilish foe, then sat silently while camouflaged enemy soldiers bayoneted them from behind or gunned them down from concealed positions. Bosley Crowther wrote that the audience with whom he watched the film “was visibly stirred” by the movie.

One other film falls into this category. The Fighting Sullivans, released in February 1944, presents the story of the five Sullivan brothers from Iowa who enlist in the Navy as a group, are posted to the cruiser USS Juneau, and meet their deaths in the naval Battle of Guadalcanal in November 1942. Most of the film unfolds in the United States, showing the five brothers as they grow to manhood, symbolizing the country as they battle each other at every step along the way but pulling together should an outsider intimidate any of them.

The wholesome family from middle America survives all challenges, only buckling when the dastardly Japanese kill all five brothers by sinking their ship. Stunned, but far from defeated, the family survivors manage their grief, and hope for a glorious end to the war comes with the film’s final scene, in which the spirits of the five deceased brothers join arms as they march to heaven.

Claudette Colbert accomplished much the same in 1944’s Since You Went Away, a film produced by David O. Selznick that highlighted the role of women in the war. Joined by a stellar cast that included Jennifer Jones, Shirley Temple in her first adult role, Hattie McDaniel, Joseph Cotton, Lionel Barrymore, and the ever-present Robert Walker, the movie presents one year in the life of a family anxiously awaiting news about and the return of their father and husband.

The film, appropriately set in a Midwest town to convey that the war touched America’s heartland, immediately divulges its focus by opening with the words, “This is a story of the Unconquerable Fortress: the American Home … 1943,” as the camera pans across familiar domestic items—photographs of childhood exploits adorning end tables, a pair of bronzed baby shoes, the husband’s pipe, left untouched since he departed.

In the midst of uncertainty and doubt stands Mrs. Hilton, the anchor around whom the other characters gather. Though plagued with her own doubts about how to handle affairs in the absence of her husband and how best to raise their two daughters, Colbert as Mrs. Hilton hits the right notes with each calamity. By film’s end she has gained confidence in herself, held the family together as a strong unit, and even taken a welder’s job in a local factory, where she labors alongside a Czech woman, an immigrant Mrs. Hilton says has a name “like nothing we ever heard at the country club.”

The girls chip in as well. Shirley Temple’s character, Brig, plants a victory garden and collects salvage while Jennifer Jones’s character, whose fiancé Robert Walker is killed in the fighting, becomes a nurse. While the family retains its strength, through the course of the film each character is challenged by the war and emerges a stronger, more complete individual.

“The Selznick characterizations are authentic to a degree seldom achieved in Hollywood,” asserted Time. “What makes Since You Went Away sure-fire is in part its homely subject matter, which has never before been so earnestly tackled in a film….”

This is an unofficial, unscientific selection of the most powerful films produced about the war’s early years. The collection provides fun, tugs at one’s heart, delivers some Academy Award performances, and sprinkles gross oversimplification and near absurdity among the handful of thoughtful scenes that asked the viewer to ponder the world situation. While one can debate the aptness of including a film or two, no one can deny that taken as a whole the movies contain the fears, doubts, joys, and emotions of a nation trapped in a world conflict few foresaw.

Author John Wukovits has written several well-received books on the Pacific War and is a regular contributor to WWII History.

Great article!

I’ve seen most of these movies, on TV Late Shows. My Dad was a kid during WWII (Pearl Harbor was attacked on his 11th birthday), he loved movies (me too), and he saw them in their initial release. We watched them on TV together when I was a teenager.

It took me quite a few years to realize that the early movies were made when the outcome of the war was far from certain. The bravery and jingoism weren’t mere theatrics — they were intended to encourage a very nervous populace that had legitimate concerns about their future.

All these decades later, these films hold up pretty well, though they’d no doubt be considered highly racist in their portrayal of Japanese.

Some of my personal favorites, in no particular order:

Sahara

Air Force

Destination Tokyo

Objective Burma

Mrs. Miniver

All Through the Night

Wake Island

Bataan

They Were Expendable

Lifeboat

So many others!