By Bryan Mark Rigg

On September 15, 1944, as Allied armies squeezed Germany from east and west, and the Third Reich needed all the experienced, able-bodied soldiers it could find, a strange but far from unusual letter was being written.

On that day an officer in the headquarters of SS head Heinrich Himmler had requested that Generalmajor Wilhelm Burgdorf, deputy chief of the Wehrmacht personnel office, dismiss from the Army on Himmler’s personal orders a colonel by the name of Ernst Bloch. Bloch, it seems, had been targeted for discharge from the service not because he was deficient as a soldier but simply because he was a Mischling—a half-Jew; his father was Jewish.

He also might have been discharged because Himmler may have discovered that Bloch had helped rescue some Jews, one of them the famous Rabbi Joseph Schneersohn, in 1939 from the SS, although this was done under the orders of his boss, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the German Secret Services (Abwehr).

Eleven days later, Burgdorf informed Himmler’s office that Bloch had been dismissed but added that in 1943 the colonel, who had earned an Iron Cross for bravery, had asked to be “sent to the front despite his several World War I wounds.” Burgdorf’s halfhearted protest did not succeed in easing Bloch’s plight. It also did not seem to matter that Bloch was described as a “positive National Socialist.”

Bloch left his post on October 27, 1944. On February 15, 1945, Hitler signed the official order discharging him because of his Jewish heritage and Burgdorf officially informed Bloch of his discharge: “The Führer has decided as of 31 January 1945 to discharge you from active duty. It is an honor to thank you on behalf of the Führer for your service rendered during war and peace for our people and fatherland. I wish you all the best for the future. Heil Hitler.”

Bloch was flabbergasted because he knew Hitler had once personally declared him deutschblütig (of German blood). However, Bloch probably did not know the particulars behind his discharge. He was simply ordered to leave, and he obeyed without questioning.

Walter Brockhoff, a close friend of Bloch’s, wrote to Bloch’s wife, Sabine, after the war to ask why his friend had been discharged. Brockhoff wrote, “One doesn’t dismiss a brave and battle-tested officer away from the front during the hour of greatest danger. There have been and will be few officers of his caliber.”

Walter Brockhoff, a close friend of Bloch’s, wrote to Bloch’s wife, Sabine, after the war to ask why his friend had been discharged. Brockhoff wrote, “One doesn’t dismiss a brave and battle-tested officer away from the front during the hour of greatest danger. There have been and will be few officers of his caliber.”

Yet the brave Bloch did not simply fold his tent and return home. As the Soviets closed in around Berlin, Bloch joined a Volkssturm (people’s militia) unit and prepared to defend the capital. He was killed during the Battle of Berlin shortly before war’s end.

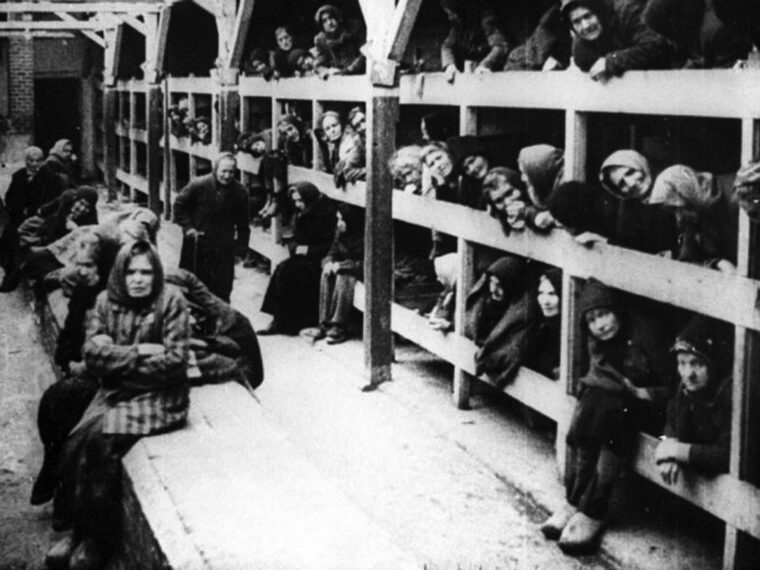

However odd the story of Ernst Bloch may seem, it is far from being an isolated case. Thousands of Mischlinge—field marshals, generals, colonels, majors, captains, lieutenants, and enlisted men—were summarily dismissed from the German military; many ended up in forced-labor camps. And many of their Jewish relatives also reached a tragic end in Nazi Germany’s slave-labor, concentration, and extermination camps.

Finding and documenting men of Jewish descent who fought in the Wehrmacht was a research project I undertook throughout most of the 1990s. The stories of the nearly 500 veterans I interviewed helped me document a largely unknown and undocumented chapter of World War II history. Many of the stories, like Ernst Bloch’s, illustrate the tragedy and complexity of German society under Hitler. And for many today, it presents several troubling issues about identity and history. This is even the case for the very subjects themselves.

By way of illustration, back in 1994 I interviewed a couple in Berlin. He, Heinz Z., was a half-Jew who had false documents during the Third Reich claiming he was an Aryan. As he discussed his time in the military, his second wife Sabine sat next to him silently listening to him describe his experiences under Hitler. Heinz told me that he felt his false documents helped him protect his first Jewish wife and their infant son. His status came under the Nazi legal designation of “privilege mixed marriage.” In other words, he helped protect his wife from persecution by staying married to her.

While Heinz was on the Russian Front in 1943, he got a notice in the mail that his wife and infant son had been deported to Poland. His commander, on learning this, immediately granted him emergency leave to put “things in order.” As Heinz explained, he thought at that moment, “What moron deports a nursing mother off to a camp?”

When Heinz arrived in Berlin and started to visit the various Nazi government offices, including the Gestapo, he learned that she had indeed been deported to the East. He tried desperately to get permission to go to the camp to bring his family back home, but the Nazis denied his request.

As the war came to an end, his unit was transferred to the Western Front where he eventually ended up in an American POW camp. After several months of internment, the Allies released him and he returned home. He quickly learned from the Nuremburg Trials and other events that documented the crimes of the Nazis that his wife and baby boy had been deported to Auschwitz. They, being the most vulnerable, were immediately gassed on arrival and then burned in the crematorium. By the time Heinz had learned of their deportation, they had already gone up the chimneys of the factories of death at this extermination camp.

As he explained this story, he fell into deep sobs. This grown man of 80 years of age crumbled and cried like a small child. I turned off my camera, walked over to Heinz and gave him a hug. I told him that if he wanted, I would return the next day to finish the interview and he could have the evening to rest. I even suggested we go for a walk to allow him to calm down.

As I backed away from him and returned to my seat, I could see that his wife, Sabine, was furious. At first, I thought she was angry at me because I had brought her husband to this emotional state, or that maybe she was upset because I hugged him and had violated German social etiquette. (Germans in general are not given to public displays of affection.)

But I soon learned that she was not upset at me at all. As she suddenly verbally laid into her husband, I quickly learned that she was shocked and angry with him because this was the first time out of 50 years of marriage that she had learned she was the second wife.

As I sat there listening to her berate him, I told them, “I think I will just leave you two alone for a while. I am sure you have plenty to talk about without me here.” I would finish the interview the next morning.

To my surprise, the wife was quite thankful that I had come because many questions she had accumulated in 50 years of marriage were answered in one evening. She and I learned many things about Heinz that helped explain some of his problems in adjusting to surviving the pain and trauma of the Nazis. She now knew why he had been so adamant about the name of their first son—it had been the name of his first son who had died in Auschwitz. She also now knew of the strange woman’s name he often yelled during his nightmares.

Bloch’s and Heinz’s stories illustrate the difficulty of understanding the Third Reich’s different shades of gray. Their stories also highlight the struggle the Nazis underwent in implementing racial policy onto a society developed by hundreds of years of assimilation between Christians and Jews, Gentiles, and Semites.

With these facts in mind, most accept as common knowledge today that persons of Jewish descent were the most endangered people under Hitler, and when considering the Nazi definition of who was a “full Jew,” they would be right. Yet, what many do not know is that probably several thousand Jews—and more than 150,000 “partial” Jews—served in the Wehrmacht, Germany’s military.

These partial Jews, so-called Mischlinge, had a much more complicated history under the Nazis than one would think especially when one knows these men were actually required to serve. This fact surprises even those who consider themselves knowledgeable about World War II and the Holocaust.

Even more surprising is how these men dealt with their situations. One partially Jewish soldier, Heinz Bleicher, observed that few people today can understand the heavy emotional burden of partial Jews during the Third Reich. Every year they felt sucked deeper into an abyss with no escape.

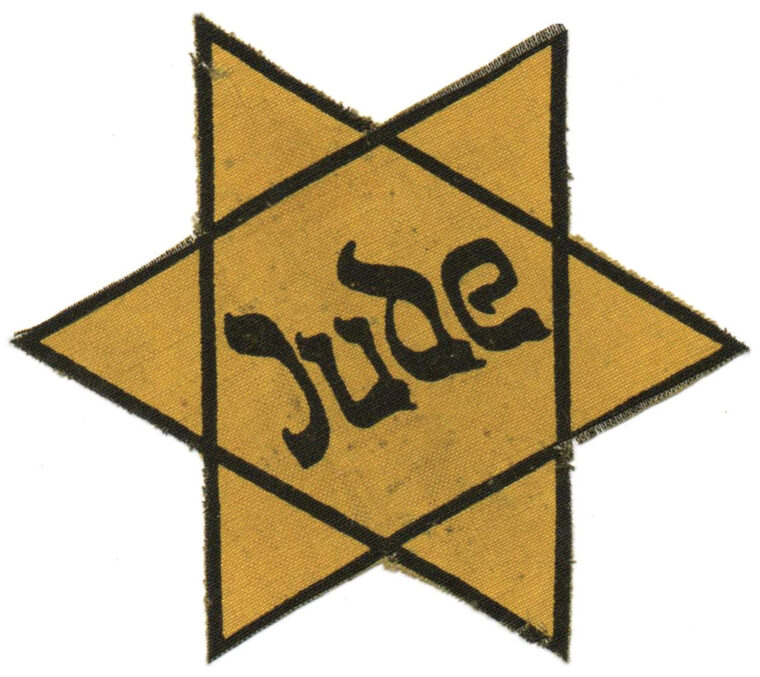

Nevertheless, until at least 1941, the Nazis drafted many into the Wehrmacht during this time of trauma and confusion. This startles most people since Hitler called Mischlinge “blood sins” and “monstrosities halfway between man and ape.” Among those were career soldiers who, because Hitler “Aryanized” them with the deutschblütig declaration, reached some of the highest ranks, though many of their relatives had to wear the yellow star and died in the Holocaust.

While lecturing from 2002 to 2013 about my books Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers, Rescued From the Reich, and Lives of Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers, I was often asked about the lives of those identified as “Hitler’s Jewish soldiers.” How could they serve? Did they consider themselves Nazis or Jews? What did Hitler know about them? What did they know about the Holocaust? Did they feel guilty about serving? Many listeners found it difficult to learn that men of Jewish descent served in Hitler’s armed forces, sometimes with great distinction.

Until recently, historians have not explored Mischling history. For some these “victims of the Holocaust” represent “embarrassing leftovers from the trauma of Hitler’s Germany.” These men often feel alone in their experience and harbor a fear that their testimony will be given “without an echo in the vast wasteland of war,” the Third Reich, and the Holocaust.

Moreover, in general, German soldiers have really “nothing to celebrate and much, including dishonor, to forget.” So it is remarkable that Jewish and Mischling soldiers have shared their experiences, which complicates an already thorny subject matter.

This “thorny subject matter” exists because Mischlinge simply do not fit into neat categories of victim or perpetrator, Jew or non-Jew. Although a few documented in this study were Jews, most were Mischlinge—a category of people that historically has no intellectual justification. Thus, it has proved challenging to explain a racial category that never existed before the Third Reich’s 1935 Nuremberg Laws.

However, what unites Mischlinge is not only the discrimination they experienced, but also their anger, frustration, fear, and sense of inferiority. Ultimately, the Nazis severely persecuted them and murdered many of their Jewish relatives, bringing them into the horrible world of the Holocaust.

The question of identity haunted many Mischlinge in general, not only those serving in the Wehrmacht. Most grew up as patriotic, Christian Germans who suddenly learned after 1933 that their nation now viewed them as inferior subhumans. The Nazis believed that being Jewish or partially Jewish made them unacceptable as full citizens. Soon after the Nazis took over power, many of these “Christian” Mischlinge soon discovered that their Christian churches, both Protestant and Catholic, had gone along with the Nazis and not only turned their backs on them but gave theological justification to persecute the Jews in the name of God and Jesus. So their identities as Germans and Christians were quickly stripped from them and they started struggling with the question: “Who am I?”

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) wrote that “government defines reality.” The Nazis violently upset the lives of millions by implementing this racial doctrine. The 19th-century political philosopher John Stuart Mill foretold what would happen to Jews and Mischlinge under the Nazis when he wrote, “Society can and does execute its own mandates: and if it issues wrong mandates instead of right … it practices a social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression.… It leaves fewer means of escape, penetrating much more deeply into details of life, and enslaving the soul itself.”

The men described in this article were persecuted by a system that issued “wrong mandates” about human value. They struggled to conform their personalities to the Nazi view of worthy Germans, yet failed to realize that their society had abandoned them. For example, Dieter Bergman wrote during the war that he represented what people wanted in a “good German.” He was tall, blond, trim, kind, good natured, and also a “warrior type.”

Yet he realized his destiny as a half-Jew hung from a pathetically slender string in an environment without refuge and legal rights. This perilous condition affected their perception of themselves and their behavior. They had to honor laws that eliminated their rights. The situation had the elements of a play in a Theater of the Absurd.

This article uses several Nazi terms to explain this history, without implying agreement with the Nazi racial theories that inspired their introduction. Nazi terms such as “half-Jew,” “quarter-Jew,” “Mischling,” “Aryan,” and “non-Aryan” come from an evil system designed to eliminate people of “inferior” ethnicity from society. The Nazis used such vocabulary to abuse and dehumanize those they deemed Untermenschen (sub-humans).

The ways the Nazis applied their racial laws did not reflect the understanding of Jewishness prevalent in German society in the 1920s. The designation “Mischling” after 1933 sounded just as foreign to Mischlinge’s ears as it does to ours.

Bergman further explained, “Half-Jewishness is a strange concept. It’s like being half-circumcised—it doesn’t exist.… However, with Hitler, we had to try to understand what being a Mischling meant. Unfortunately, we were slow learners.”

Events beyond their understanding and coping mechanisms simply beleaguered most Mischlinge. For example, Heinz Gerlach wrote Minister of Education Bernhard Rust in 1941, “I cannot help it that I’m a Mischling. Also, no one should blame my parents for my situation. They married during a time without racial laws.”

Gerlach further clarified that his mother looked and acted like an “Aryan” and that his father’s family never thought twice about accepting her. He wrote that she had proven her disapproval of Judaism by marrying a Christian, baptizing her son a Christian, and raising him to “love his Fatherland and the Führer.” Gerlach struggled with the Nazis defining him partially Jewish—a part of his background he had never accepted.

The lives of Jews and Mischlinge show how the racial laws affected them on a personal level, the extent of their persecution, and the divided loyalties many toiled with during the Nazi years and afterward. Their lives seemed ludicrous when they served in the military while the Nazis persecuted their family members.

As a full-Jew, Captain Erich Rose told his friend, General Albert Schnez, “I’m a Schwein. The Nazis murdered my family (which I have to assume), and at the same time, I fight for them.”

Yet, most did serve, and when one learns more about German society, this service does not seem so strange. Most German Jews and Mischlinge grew up in an environment where their elders conditioned them to have a strong obedience to authority. They learned to obey their parents, teachers, clergymen and, most importantly, their government. German society conditioned people to believe that the authority of superiors was based on “greater insight and more humane wisdom.”

In the military, this submission was explicit. After the war, Gustav Knickrehm said, “‘The advantage of our armed forces lay in this monstrous training.… You carried out all orders automatically.… You acted automatically as a soldier.…’”

Mischlinge learned Kadavergehorsam, or slavish obedience, even if it infringed on their personal freedom and the human rights of their family. In other words, the Nazis imposed “political and ideological conformity” on all subjects under their rule. Whatever Hitler ordered, they had to obey, and they did so almost willingly because of their culture. Those who did not obey Nazi laws wound up in concentration camps or in front of a firing squad.

Also fundamental to comprehending the bizarre situation where men wore the swastika on their uniforms while their relatives had to wear the Star of David is an understanding of their Jewishness. Most parents of Mischlinge did not raise them as religious Jews, and most Mischlinge did not consider themselves Jewish until Hitler persecuted them. But Nazi racial laws considered them all Jewish to one degree or another.

On November 14, 1935, the Nazis issued a supplement to the Nuremberg Laws of September 15, 1935, that created the “racial” categories of German, Jew, “half-Jew (Jewish Mischlinge 1st Degree),” and “quarter-Jew (Jewish Mischlinge 2nd Degree),” each with its own regulations. These laws distinguished Germans from persons of Jewish heritage both biologically and socially. Full Jews had three or four Jewish grandparents, half-Jews had two Jewish grandparents, and quarter-Jews had one Jewish grandparent. If a person not of Jewish descent practiced the Jewish religion, the Nazis also counted him or her as a Jew.

The Nazis resorted to religious records to define these “racial” categories, using birth, baptismal, and marriage and death certificates stored in churches, temples, Jewish community centers, and courthouses.

The 1935 Nuremberg Laws provided the basis for further anti-Jewish legislation to preserve the purity of the “Aryan” race. The Nazis based their racial laws on the völkisch (ethnical in a racial sense) notion of the inherent superiority of the “Aryans.” These laws provided civil rights to those belonging to the Volk and having German “blood.” This created a “new morality which, in terms of the old system of values, seemed both unscrupulous and brutal.”

The Nazis automatically denied Jews and Mischlinge citizenship privileges. However, under Article 7 of a supplementary decree of the Nuremberg Laws, Hitler could free individuals from the labels Jew or Mischlinge by aryanizing them with a stroke of his pen. In fact, Hitler allowed several high-ranking officers of Jewish descent to remain in the military by “aryanizing” them. Two of these were second in command of the Luftwaffe: Field Marshal and half-Jew Erhard Milch and General and half-Jew Helmut Wilberg, the brilliant strategist who helped develop the operational concept of Blitzkrieg.

But most Mischlinge did not receive this clemency, and the German authorities despised them as an unwelcome minority. Most Nazis considered Mischlinge as predominantly Jewish and wanted them treated as such. Both the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, and his general Reinhard Heydrich wanted Mischlinge exterminated like the full Jews. But pressure on the SS and party by “Aryan” relatives, prominent families, the military, and the government postponed the issue of how to deal with Mischlinge until after the war.

In addition to the racial laws, an essential element of this history explores Halacha (Jewish Law), which considers more of the men in this study Jewish (full-Jews) than the Nazi racial laws did. Since the Nazis considered anyone who practiced the Jewish religion a full-Jew, most Mischlinge were, by definition, Christians.

However, according to Halacha, the majority of half-Jews documented would be considered Jewish because they had Jewish mothers, since only mothers determine Jewish identity according to Halacha.

Not only do Nazi racial laws and Halacha make it difficult to understand Mischlinge, but the way many developed private connections to Judaism complicates how one judges them today. Many developed Jewish identities, but the majority of those identities were born out of persecution rather than cultural or religious upbringing. Today, some Mischlinge feel Jewish, though their Jewish identity is private and complicated.

The following story illustrates the difficulties one encounters when identifying a Jew for the purposes of this research. After World War II, Wehrmacht veteran Karl-Heinz Maier decided to do something for his Jewish family. He traveled to Israel and fought in its War of Independence. Even after becoming a major, the local authorities did not consider him Jewish because his father, rather than his mother, was Jewish.

For 12 years, Maier explained, the Nazis persecuted him because he had a Jewish father, but the Israelis called him a goy (a derogatory Yiddish term for Gentile) because of his Gentile mother. Although he could fight for the Israeli Army, the government did not consider him Jewish.

The same type of identity crisis that Maier experienced also happened to tens of thousands of Mischlinge during—and some even after—the Third Reich. So differences in religious belief, cultural background, ethnic makeup, historical experiences and self-perception often make it difficult to answer the question, “Who is a Jew?”

Before this study, documented in Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers, it was widely unknown that probably a few thousand full, and tens of thousands of half- and quarter-Jews, as classified by the Nazis, served in the German Armed Forces during World War II. After examining assimilation records, birth rates, and mixed-marriage rates with mathematicians and statisticians, this study estimates that 60,000 half-Jews and 90,000 quarter-Jews served in the Wehrmacht.

Some, as mentioned, served as high-ranking officers, including generals, admirals, and even one field marshal. Full Jews who served did so with false documents; their commanders believed them to be “Aryans.” The estimated numbers of Jews and Mischlinge in the Wehrmacht have caused controversy because the assimilation records or definitions of Jewishness have not been carefully analyzed and deserve a closer look.

If one contends that Mischlinge were not Jewish because they had been born into Christian families, had converted, had not practiced Judaism, had not felt Jewish, or had only received this label from the Nazis, then one must also reevaluate the figure of six million Jews who died in the Holocaust. Tens of thousands of those exterminated did not consider themselves Jewish, but the Nazis labeled and treated them so. For instance, the Nazis sent the philosopher Edith Stein to the Auschwitz gas chambers even though she had converted to Christianity.

Hitler had cynically described the conversion process: “If worst came to worst, a splash of baptismal water could always save the business and the Jew at the same time.” The Nazis, he said, would make sure that “the ability to camouflage ancestry by changing religions will completely disappear.”

The reader will therefore not find it surprising that the Nazis deported countless converted parents, grandparents, and relatives of the Mischlinge documented in this study to Hitler’s death camps. As Holocaust expert Martin Gilbert wrote, “Tens of thousands of German Jews were not Jews at all in their own eyes.”

Half-Jew Dieter Bergman said, “I lost over a dozen relatives in the Holocaust and most of them wouldn’t have called themselves Jews—they’d converted to Christianity for Christ’s sake.” Half-Jew Hans Günzel, who lost 57 relatives in the Holocaust, expressed his confusion about the Nazi definition of Jewishness when he claimed, “The sad thing about all of their deaths is that most had converted to Christianity and didn’t consider themselves Jews.”

Even though an estimated 50,000 Jewish converts to Christianity lived in Germany in 1933, the Nazis treated them as racial Jews. They also did so in other countries. For example, Chaim Kaplan, a distinguished principal of a Warsaw Hebrew school, took pleasure in 1939 in seeing that the Nazis treated Jewish converts to Christianity no differently than religious Jews.

He wrote “I shall, however, have revenge on our ‘converts.’ I will laugh aloud at the sight of their tragedy. These poor creatures … should have known that the ‘racial’ laws do not differentiate between Jews who become Christians and those who retain their faith. Conversion brought them but small deliverance…. This is the first time in my life that a feeling of vengeance has given me pleasure.”

Obviously, many Polish Jewish converts to Christianity had hoped their new religion would protect them, something that Kaplan described as painfully mistaken.

Furthermore, the Nazis labeled half-Jews in Poland and Russia as full Jews because they did not have “Aryan blood” and Gentile relatives to protect them. Although most of these partial-Jews had assimilated into Christian society and converted to Christianity, the Nazis marked these non-German Mischlinge in the eastern territories for extermination. They died in the Nazi camps as Jews.

The Reich Security Main Office for the Eastern Territories stated in the summer of 1941, “In view of the Final Solution … anyone who has one parent who is a Jew will also count as a Jew.”

Hans Frank, the governor-general of occupied Poland, included Mischlinge in his plan of extermination in a report on December 16, 1941: “We have in the General Government [i.e., occupied Poland] an estimated 2.5 million, maybe together with Mischlinge and all that hangs on, 3.5 million Jews. We can’t poison them, but we will be able to take some kind of action which will lead to an annihilation success…. The General Government will be just as judenfrei [free of Jews] as the Reich.”

Consequently, hundreds of thousands of converts to Christianity and non-German Mischlinge ultimately died in the Holocaust, and many of them, tragically, had relatives serving in the Wehrmacht.

With these facts in mind, if one argues that the men documented in this study are not really Jewish, then that same person must also reevaluate his definition of Jewishness when discussing “Jewish” Holocaust victims.

While it may be difficult to accept the fundamental concept of “Hitler’s Jewish soldiers,” there is one key sense in which this phrase is accurate. Hitler’s racial laws designated Mischlinge as “Jewish” or “part Jewish.” They were only “Hitler’s Jewish soldiers” and no one else’s, since the majority of the German Jewish population and many Mischlinge seemed not to share Hitler’s definition.

People often ask, “How could those affected by these laws serve?” Most Mischlinge served because they were drafted by the Wehrmacht which, until 1940, required half-Jews to serve. However, they could not become NCOs or officers without Hitler’s personal approval.

In April 1940, Hitler decided to order the discharge of half-Jews from the armed forces because their presence created problems. Many came home after the Poland campaign in 1939 to find that the authorities had severely persecuted their relatives. Hitler did not want to protect Jewish parents and grandparents because of the service of their children and grandchildren, so he ordered their dismissal.

Many, however, remained on active duty, with exemptions from Hitler or because they had hidden their Jewish ancestry. Also, several stayed with their units for months after this discharge order, because of the war with Norway in April and the invasion of France in May of 1940, which slowed the bureaucratic process of discharging them.

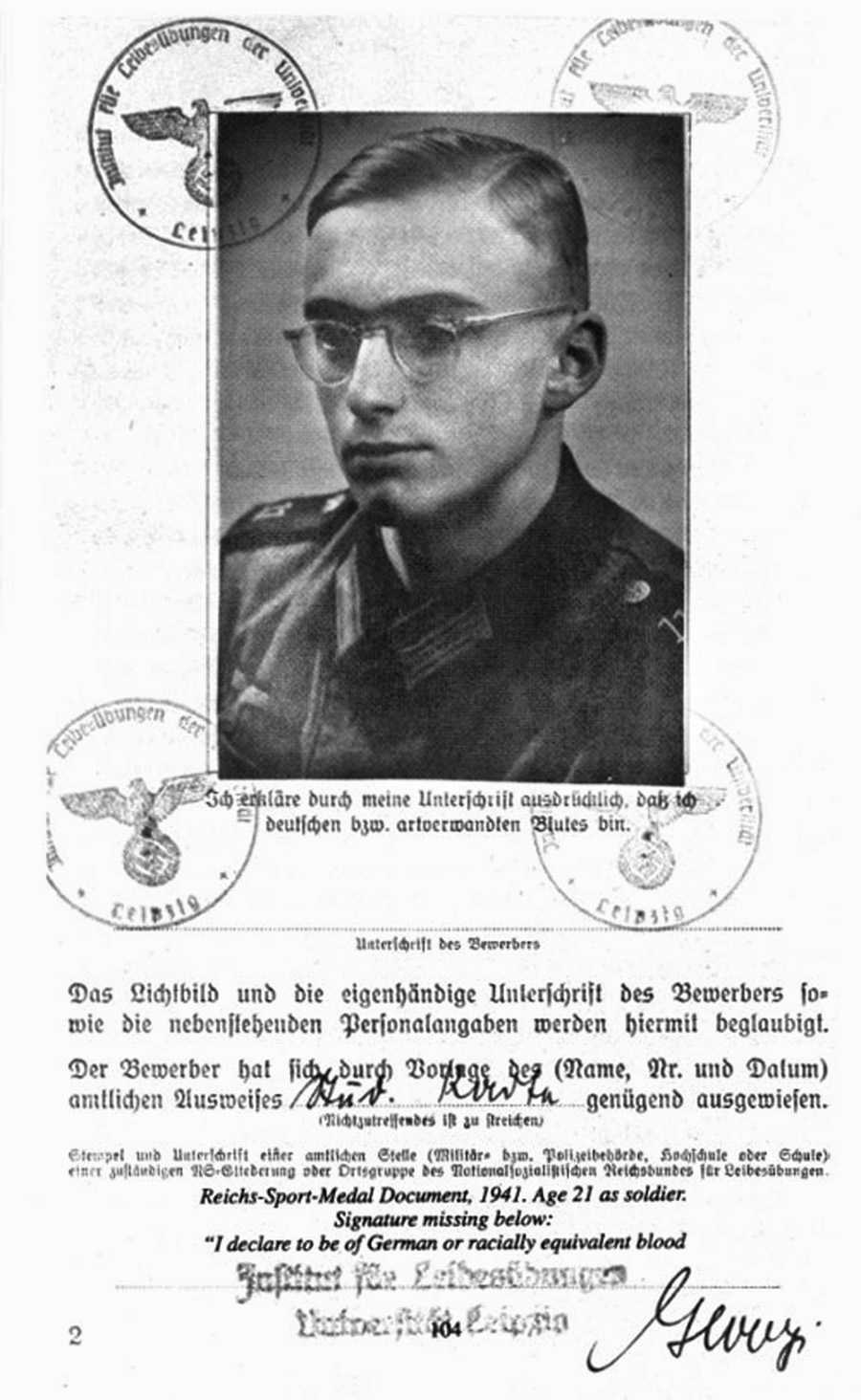

The authorities did not widely enforce this discharge order until late summer 1940, and even then, many officers ignored it. In addition, the search for half-Jews in the service often consisted solely of requiring soldiers to sign ancestry declarations stating they were not Jews. Many Mischlinge signed this statement in good faith, since they were not Jews according to their understanding. Others just lied and remained with their units.

Known half-Jews who had won combat medals or battlefield promotions could apply for an exemption from the racial laws, enabling them to remain in the Wehrmacht because of their valor; thousands submitted applications. Even before 1940, several half-Jewish officers had received exemptions from Hitler and obtained high ranks.

The military also drafted quarter-Jews. Unlike the half-Jews, they had to serve throughout the entire war. Yet they, like their half-Jewish counterparts, could not become NCOs or officers without Hitler’s approval.

The majority of half-Jews discharged after April 1940 returned home and resumed their studies if they had distinguished military records or found work until 1944. Then Hitler had them, as well as other nonveteran half-Jews, deported to forced-labor camps of the Organization Todt (OT). They were joined there by the “Aryan” husbands of Jewish wives, many of whom were their fathers. Fortunately, they were not in the camps long, and their treatment there was less severe than in the concentration camps. Thus, most survived these places of persecution.

The Nazis treated these partial Jews as objects without any self-determination. Hitler probably would have further persecuted and in many cases exterminated them had he won the war.

After the war, neither “Jewish identity” nor “Jewish loyalty” played any role in their lives. Some embraced their Jewishness and now call themselves Jews. Others acknowledge their Jewish roots, but would not call themselves Jewish in any sense of the word. Many have wrestled with questions about themselves and their role in society in light of their Jewish background throughout their lives. These men acknowledge their Jewishness but feel bewildered as to what this means in practical terms.

These men’s stories illustrate the wide range of experiences one could have under the Third Reich and how complicated it was for the Nazis to implement racial policy. The trauma that thousands of mothers, sisters, wives, and girlfriends suffered by being connected to them broadens the scope of the tragedy of this chapter of the Holocaust. The lives of many Mischlinge and some Jews in the Wehrmacht were traumatic, filled with difficult choices and painful experiences.

Some came from families with strong military traditions that encouraged them to accept service under the Third Reich as natural and honorable. Their fathers and uncles had served in World War I, and a few, like Field Marshal Milch and General Wilberg, had even distinguished themselves in the “Great War,” giving them a strong foundation of military service before Nazism. The majority of their families and most of these men had equal rights in Germany, only to have them quickly taken away once Hitler came into power.

The stories of Mischlinge show in vivid detail that these men fought for a government that took away their basic human rights and sent their relatives to extermination centers. (It also should not be forgotten that the U.S. military segregated and discriminated against its black troops and forcibly removed Japanese Americans from the West Coast and relocated them to American “concentration camps.”)

Nevertheless, most Mischlinge continued to serve, since any open resistance would have cost them their lives.

The fact that their “Aryan” superiors—including Hitler’s Army adjutant Gerhard Engel and Domestic Officer in the Wehrmacht office Commander Richard Frey—courageously helped many of them added to their belief that their service would help protect them. Their superiors often disregarded the Nazi racial laws, valuing a trained soldier and true comrade more than Nazi regulations. This helps explain why many of these men remained loyal.

The passionate patriotism felt by many Mischlinge is ironic. When drafted, most thought it their duty to obey, though the Nazis persecuted them and their families. As half-Jew Dieter Bergmann said, “I loved my Fatherland, and most half-Jews I knew all believed they were fulfilling their duty to Germany. We loved Germany and wanted to see her become great again. Unfortunately, we were lied to and were abused by the very country we held so dear.” Nazi policy toward Mischlinge gradually worsened and pushed them toward the world of the Holocaust.

Hitler refused to use these patriotic citizens to help win the war. This demonstrates how Hitler valued racial purity over military victory. From 1942 to 1944, Hitler assigned hundreds of trains to move millions of Jews across Europe to the death factories in Poland when the Army could have used those trains to move troops and war matérial.

Despite the constant labor shortage, Hitler exterminated millions of Jews who could have worked in factories. Hitler had discharged tens of thousands of half-Jews from military service by late 1942 when Germany encountered severe setbacks at Stalingrad. He could have recalled these men, who most probably would have fought bravely.

Hitler’s racial policies turned most Mischlinge against him and his government. The majority of them looked forward to the day of Hitler’s demise. Half-Jew Helmut Krüger admitted that had Hitler not discriminated against him, he probably would have become a Nazi. When asked why, he simply explained how difficult it is today for people to understand how attractive the movement was to young men. In front of “the evil goals of the Nazis stood the wonderful activities for young men of camping, war games, and community,” he said. “It all just felt so good.”

Just as shocking as Hitler’s perverse racial policies with respect to partial-Jews in the Wehrmacht is that most Mischlinge soldiers did not know Hitler was murdering millions of Jews, including their relatives; the octagenarian Heinz Z., mentioned earlier, experienced losing his wife and infant son in Auschwitz while he fought on the Russian Front.

Like most other Germans, they knew about Nazi deportations, but what happened at the deadly destinations lay beyond their knowledge or imagination, as illustrated by Heinz’s attempt to go to the very camp to which his wife and child had been deported. Some knew about executions in the East but not the systematic killing of millions in gas chambers.

The most convincing proof that these men did not know what was happening is the story of half-Jews in the OT forced-labor camps. Had half-Jews known about the Holocaust, one would expect them to have done everything they could to have avoided their own deportations. But as my research revealed, most reported when called, even though most had weeks if not a month before they were “required” to report to their train station to be shipped off to an unknown work camp.

Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer wrote, “The Jews were the products of a civilization which stood in stark contradiction to all the premises of Nazism. It was totally incomprehensible to them that people should exist who denied the sanctity of human life, or who excluded some people from humanity altogether. They were therefore outwitted at every point, easily misled, and murdered precisely because they could not accept the reality of the world in which such murder was possible.”

Hitler’s constant attention to the details of Mischling policy support the assumption that he was at least as intimately involved in their extermination as in that of the Jews. As Hitler told district party leaders when discussing the Jewish issue, “Who can give the order? Only I.”

Yet the Mischling story offers much more than exploring Nazi discrimination, persecution, and injustice. Many Mischlinge did a great deal to protect their relatives and others saved Jews to whom they had no previous connection. Ernst Bloch, mentioned at the beginning of this article, saved the famous Lubavitch Rebbe, Joseph Schneersohn, and 20 of his followers and family members. We also see courage, generosity, and self-sacrifice in the face of great danger.

Unfortunately, we also see evil in the lives of some Mischlinge. Field Marshal Milch, a Nazi, represents a Mischling who turned himself over to Hitler and his goals. In the end, he served time as a Nazi war criminal. Luckily, this disgusting person was a member of a tiny minority among the Mischlinge.

Contemporary genocide does not only happen in Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Rwanda, and Bosnia. Genocide begins with discriminatory and prejudicial thoughts long before anyone dies, as was obvious with Nazism under Hitler and, moreover, like we see today with radical Islam (Islamic Fascists) present in Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Syria, Egypt, and Libya, to name but a few that deny people religious freedom and refuse women basic human rights.

How we learn to think about others and their worth makes all the difference. The Mischlinge remind us how important it is to fight vigilantly against our tendency to denigrate others for bolstering our own faltering self-esteem. It also reminds us that we all need to fight against those who do not have the intelligence or humility to realize exclusive ideology and religion breed lethal convictions leading to persecution and murder.

A person who is raised as a Christian and considers himself to be a Christian is not a Jew, regardless of what Hitler thought. Putting non-religious Jews into this same category is completely wrong. A person may be a non practicing Jew, yet identify himself as Jewish and feel part of the Jewish community. It is wrong to equate the non religious Jews put to death in the holocaust with those that never considered themselves to be Jewish and who served in the German armed forces.