By Victor Kamenir

On the evening of June 21, 1941, foreboding hung like a heavy blanket over the Soviet Union’s western border as indicators of the imminent German invasion increased every day. At night, border guards in their observation posts listened to the rumble of vehicles on the German-occupied Polish side of the frontier. Unwilling to provoke Hitler until they were ready for war, Soviet leadership strictly enforced the outward appearance of calm and peace.

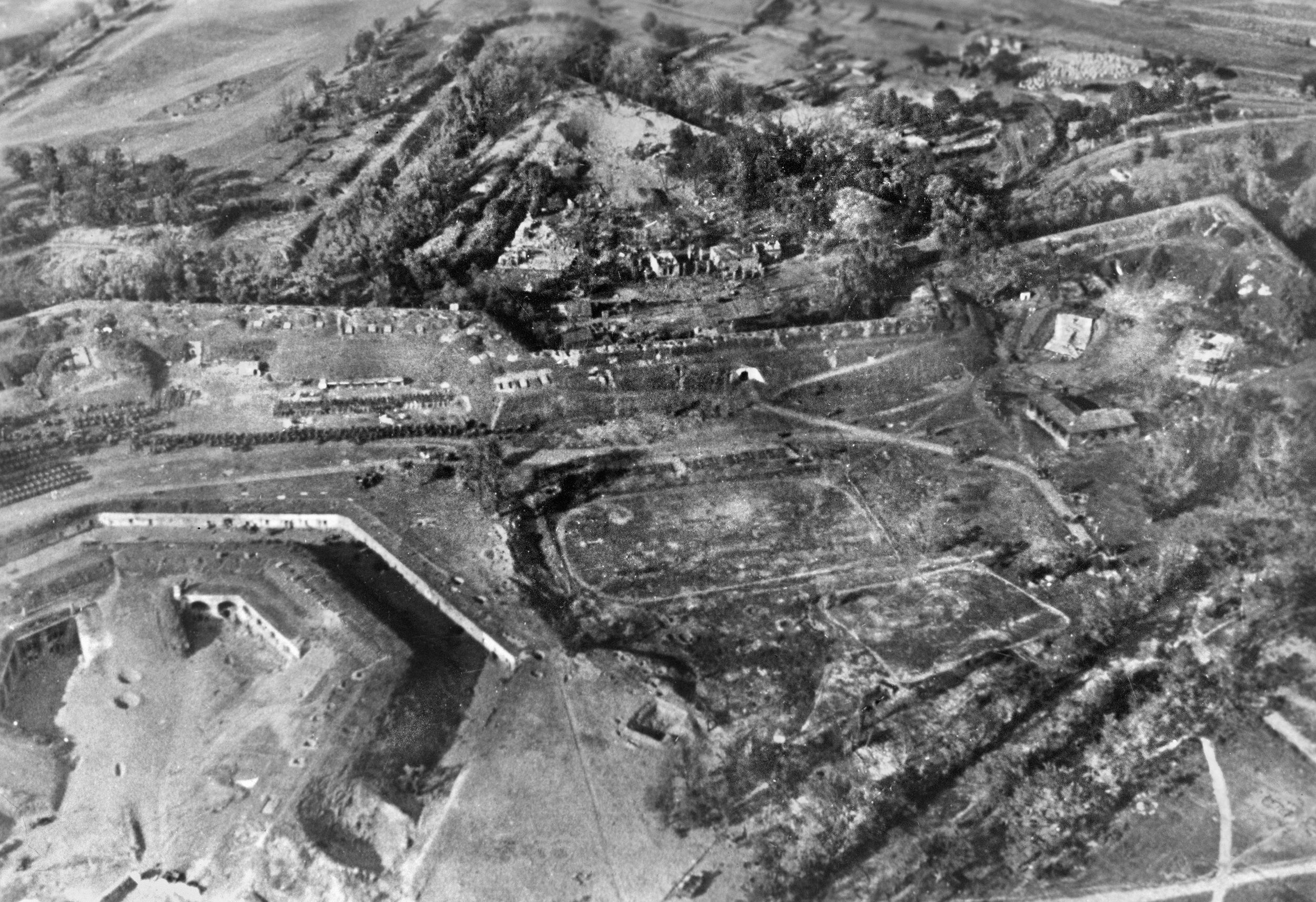

After dividing Poland with Hitler’s Germany in 1939, Stalin’s Soviet Union gained a large swath of territory, including the city of Brest with its red-brick fortress in the southwest corner of Belarus. In 1833, when eastern Poland was part of the Russian Empire, military engineers began constructing a fortress at the confluence of the Western Bug and Mukhavets Rivers on the site of a dilapidated castle built during the late Renaissance period. Although construction on the main complex concluded in 1862, additions and improvements continued until World War I, including two outer rings of small forts and fortified positions.

The Western Bug River and two branches of the Mukhavets River flowed around the naturally formed Central Island. Water diverted from the two rivers into artificial channels, creating three more islands: West, North, and South.

The Citadel was the heart of the fortress, a massive two-story oval building on the Central Island with sufficient space to accommodate up to 12,000 soldiers and their equipment. Commonly called the ring barracks, the building was more than a mile in circumference, with outer walls up to two meters thick. Many of the Citadel’s 500 self-contained fighting compartments on the first floor were configured as positions for artillery and crew-served weapons. If a compartment fell, the enemy would have to go through the inner courtyard or blow out a wall to reach a neighboring compartment.

Except for a gap in the northeast end of the Central Island, the ring barracks encircled a large courtyard with multiple stand-alone buildings. The most prominent were the White Palace, a former Basilian Monastery converted into an enlisted club; the Engineering Directorate, a former St. Nicholas Church converted into a club and administration building; and the barracks of the 333rd Infantry Regiment. Extensive basements connected the Citadel with multiple buildings in the inner courtyard.

Four tunnel-like gates ran through the lower level of the Citadel to the bridges to the other three islands. The Terespol Gate led to the West Island, and the Kholm Gate connected with the South Island. Two bridges connected the Citadel with the North Island: one via the Three-Arch (Brest) Gate on the north side of the ring barracks and another via the Bialystok Gate leading to the southeast corner of the North Island.

A 30-foot-tall earthen embankment ran along the outer perimeters of the three outer islands, with more self-contained fighting and storage compartments built into the inner side. Smaller stand-alone fieldworks reinforced the main embarkment. On the North Island, East and West forts flanked the main road leading from the fortress to the city of Brest. Each fort featured two horseshoe-shaped fortified embankments, one inside the other, with a two-story fortified blockhouse in the inner courtyard.

Modern weapons rendered the fortress obsolete as a defensive position—the Soviet Army only utilized it and its two sub-posts north and south of the city to garrison troops.

The primary resident Red Army units were: the 6th and 42nd Rifle Divisions, the 33rd Engineer Regiment from the 28th Rifle Corps of the 4th Army, two hospitals, and a detachment of NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, later Committee for State Security or KGB) Border Guards troops.

In the sub-post immediately south of the fortress, the 22nd Tank Division from the 14th Mechanized Corps of the 4th Army occupied modern barracks vacated by the Polish army in 1939. One rifle and one artillery regiment from the 42nd Rifle Division were in Zhabinka, twenty kilometers east of Brest and additional 28th Rifle Corps organic assets were in the northern subpost. More than 400 officer families lived inside the fortress and off-site housing. In the southwest corner of the North Island was the old Bridgettine monastery, converted into a prison holding Polish POWs and political prisoners alongside common criminals.

By the end of Saturday, June 21, 11 of the 18 infantry battalions from the 6th and 42nd Rifle Divisions and the majority of the 33rdEngineer Regiment were outside the fortress, constructing field fortifications along the border. Artillery units from the 28th Rifle Corps and the two rifle divisions gathered at the firing range co-located with the 22nd Tank Division in preparation for scheduled maneuvers on Sunday. Some 9,000 soldiers from various units remained in the fortress.

In a major oversight that proved fatal, the headquarters of the two rifle divisions and the 28th Rifle Corps were in the city, where the senior Soviet officers took advantage of luxurious quarters formerly occupied by Polish officers and officials.

In case of war, the mission of the regular army troops was not to defend the fortress but to occupy fieldworks along the border. Based on previous German behavior patterns, Soviet leadership expected hostilities to be preceded by a period of escalated tension. The pre-war plans anticipated the rifle divisions to have sufficient time to exit the fortress, stage at Zhabinka, and then deploy forward to predetermined positions.

The German blitzkrieg war concept called for rapid penetration of enemy territory, encirclement, and destruction of the bulk of enemy forces. The significance of the Brest Fortress was not its defensive value but its location astride a major railroad nexus and seven bridges in the immediate vicinity of the city of Brest.

General Heinz Guderian’s 2nd Panzer Army was one of the German armored fists ready to strike into Belarus. Having captured the Brest Fortress from the Poles in 1939, Guderian knew he needed additional infantry forces to open the way for his panzer and motorized divisions. The German High Command attached Gen. Walther Schroth’s XII Army Corps to Gudeiran’s command, at his request.

Schroth deployed the 45th Infantry Division on a five-kilometer front centered on the fortress. The other two divisions, the 31st and 34th, would attack on its flanks, with the 31st Infantry Division on the left to assist the 45th Infantry Division in capturing Brest.

Major General Fritz Schlieper recently took command of the 45th Infantry Division, activated in 1938 based on the former Austrian 4th Division. The division was a well-trained veteran formation after two campaigns in Poland and France.

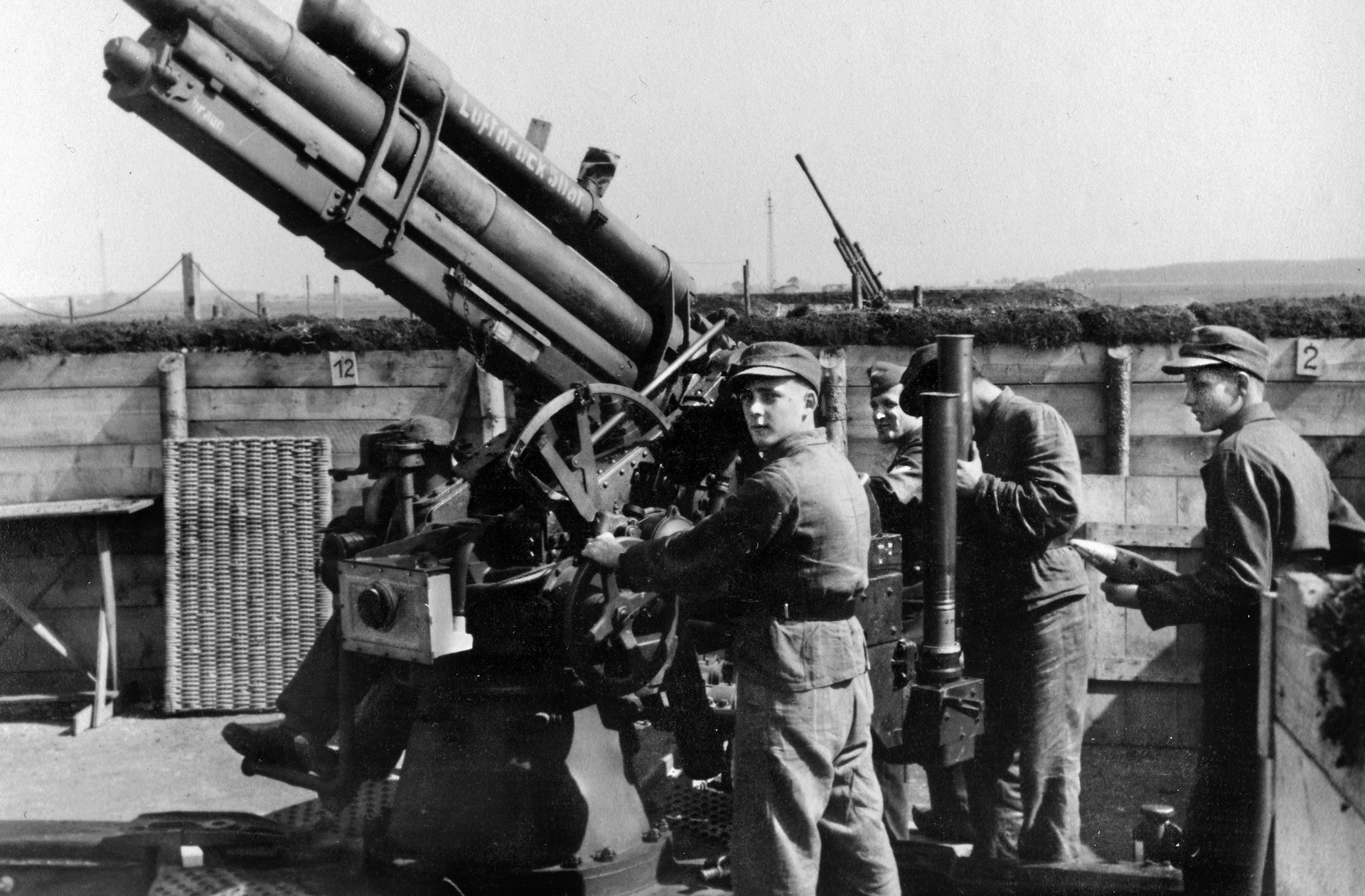

A separate artillery command to support the 45th Infantry Division unified the division’s organic artillery—three batteries of 210mm mortars, two battalions of 150mm Nebelwerfer rocket launchers, and a battery of two 600mm Karl-Gerät “Big Karl” mortars. Several aerostats provided observation and artillery correction support.

The 130th Infantry Regiment from the 45th Infantry Division would strike on the division’s right flank (south). Its 1st and 2nd battalions were to attack the South Island and attempt to reach the Citadel via the Kholm Gate. The 3rd Battalions were to skirt the fortress from the east and rush for four bridges over the Mukhavets River east of Brest.

On the left, two battalions from the 135th Infantry Regiment attacked the North and West Islands. After achieving their initial objectives, both regiments were to continue on to capture the Citadel. Third battalion remained in the division’s reserve, while the 133rd Infantry Regiment was held back in the XII Army Corps reserve.

The Germans had captured the fortress in 1939 and possessed maps and photographs of it. Based on available information, the command staff of the 45th Infantry Division created a sand table to wargame its mission, which called for the fortress to be captured in eight hours.

In the evening of Saturday 21, 1941, most Soviet officers returned to off-site housing to spend the Sunday with their families, as was the common practice. Mainly, unmarried junior lieutenants remained in the fortress with their units. Regimental Commissar Yefim Fomin, recently assigned deputy commander of the 84th Rifle Regiment, had plans to take a train to his previous duty station in Latvia to bring his family to Brest. Unable to purchase train tickets on Saturday, he returned to the fortress and slept in his office.

Shortly after 2 a.m. on Sunday, June 22, 1941, German reconnaissance groups and the Fifth Column saboteurs in Brest disrupted electricity and telephone lines and took up positions on rooftops at strategic locations throughout the city.

At 4 a.m., a German assault party rushed the Soviet guards on the main railroad bridge and quickly overwhelmed them. At the same time, another assault party in inflatable rubber boats headed across the Bug River toward the prison in the west corner of the North Island. Fifteen minutes later, a massive artillery barrage drowned the sounds of minor skirmishes.

Heavy caliber shells rained on the sleeping fortress. Walls and roofs collapsed, killing soldiers in their bunks or burying them alive under rubble. Anything that could burn caught fire. Exploding vehicle gas tanks added oily smoke to the carnage. In the ensuing chaos, partially dressed panicked soldiers and family members jumped out of windows or ran from the buildings into a vortex of explosions. Inhuman screams of wounded and dying artillery horses, tethered in the open, contributed to the cacophony of slaughter.

As the officers living at off-site housing areas rushed to the fortress, many were cut down by shell fragments as they ran through the gauntlet of fire. The few who reached their units did their best to lead their frequently undressed and unarmed men out of the fortress. With German artillery targeting gates and bridges, escaping soldiers and civilians had to traverse choke points under accurate interdiction fire. Suffering heavy casualties, roughly half of the troops eventually made it out of the fortress before the mousetrap snapped shut in the early afternoon, leaving between 4,000 and 5,000 soldiers trapped inside.

At 4:15 a.m., German infantry assault parties reinforced with combat engineers from the 81st Engineer Battalion launched their inflatable boats into the water. At the same time, additional engineer crews began assembling a two-ton pontoon bridge from the west bank of the Bug River to the North Island.

Every four minutes, artillery fire shifted forward 100 meters, closely followed by German infantry. When the shells began to fall, roughly 400 Soviet soldiers from duty companies and the border guards were under arms, and many of them became casualties in the opening minutes of the conflict. Amid panic and confusion, few Soviet soldiers fought back, and German assault parties made rapid progress. During the first half hour, German artillery fired 5,360 rounds—180 per minute—concentrating primarily on the North Island and the Citadel.

As the first soldiers from the 3rd Battalion/135th Infantry Regiment jumped ashore on the West Island, the few Soviet Border Guards still alive at their posts cut loose with machine guns. Even surrounded, border guards fought to the death, and the Germans found it easier to contain and bypass them. Leading elements of the 3rd Battalion reached the Citadel from the West Island via Terespol Gate. As the Germans entered the inner courtyard and continued east, they ran into an ambush from several directions. Under the command of Sr. Lt. Aleksandr Potapov (333rd Rifle Regiment) and Border Guard Lt. Andrei Kizhevatov, two groups of Soviet soldiers unleashed a withering fusillade. Master Sergeant Samvel Matevosian from the 84th Rifle Regiment led a counterattack to engage the Germans in hand-to-hand combat. Under a furious attack, most of the 3rd Battalion retreated to a small perimeter in the southwest corner of the ring barracks, while some 70 men from the 3rd Battalion and the 81stEngineer Battalion took shelter in the large former church building. Although cut off, the Germans in the former church occupied a key position, allowing them to fire on the inner side of the ring barracks.

The men from the 1st Battalion/135th Infantry Regiment added their weight to the fight at the prison on the North Island, where the Soviet guards fought to the death. Pressing forward, they ran into spirited defense on the north-central side of the North Island, where Maj. Pyotr Gavrilov, commander of the 44th Rifle Regiment, organized a large group of men from various units. At the East Fort, soldiers from the 393rd Air Defense Battalion manned two anti-aircraft guns and a quad machine gun, and the gunners from the 98th Anti-Tank Battalion manhandled two 45mm guns to the top of the embankment.

While the Germans were still confined to the west end of the North Island and the bank of the Mukhavets River, Soviet soldiers streamed out of the fortress through the north gates. In and around the West Fort, Battalion Commissar Sergei Derbenyov and Capt. Vladimir Shablosnki, battalion commander from the 125th Rifle Regiment, organized a rear guard, allowing most of their regiment under Maj. Aleksandr Dulkait to withdraw. However, the next day, the remnants of the 125th Regiment were surrounded and destroyed. Wounded and captured, Dulkait died in captivity of tuberculosis in April 1945.

Part of the German battalion bypassed the two strong forts and attempted to enter the Citadel via the Three-Arch (Brest) Gate in the northern sector of the ring barracks. However, they were halted by the men from the 44th Rifle Regiment under Capt. Ivan Zubachev and Lt. Anatoliy Vinogradov from the 455th Rifle Regiment.

On his own authority, Col. Friedrich-Wilhelm John, commander of the 135th Infantry Regiment, diverted a self-propelled tank destroyer battery from the 31st Panzerjager Battalion, 31st Infantry Division to reach his surrounded men from the north. Although one of the vehicles managed to cross the bridge, the open-topped superstructure made the crews vulnerable to accurate sniper fire from the second floor of the ring barracks. After suffering one man killed and six wounded, the tank destroyers pulled back.

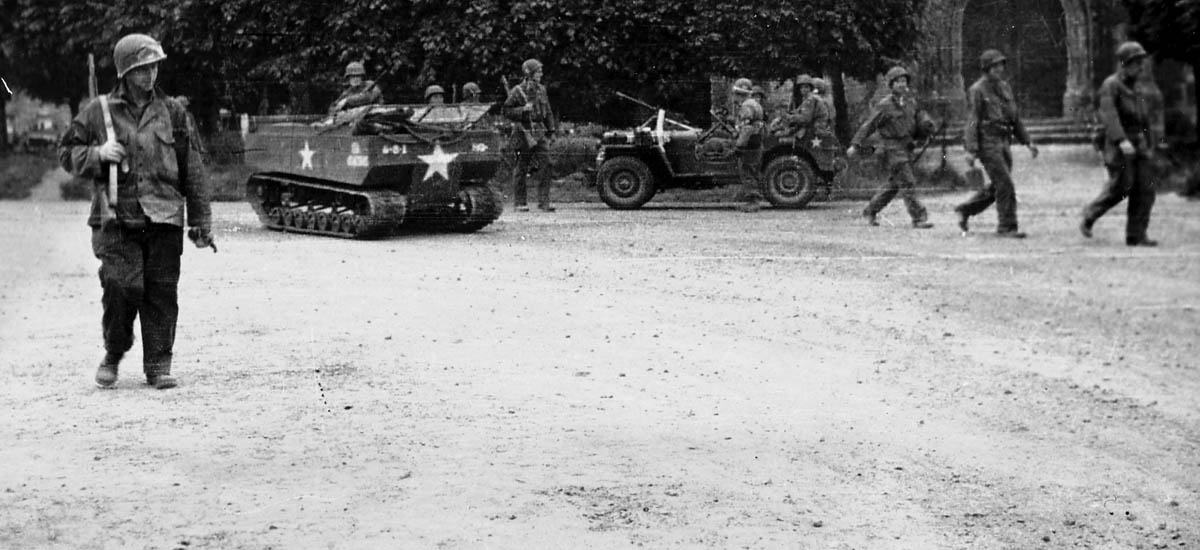

In the south, two battalions from the 130th Infantry Regiment rapidly crossed the Bug River and attacked the South Island, quickly overrunning most of it. Its third battalion skirted the fortress around the east and raced for the four bridges over the Mukhavets River. The Germans quickly captured two bridges closest to the southeast end of Brest while the reconnaissance detachments pressed forward and occupied several city blocks.

On the South Island, occupied mainly by two hospitals and multiple supply warehouses, attacking German soldiers encountered chaos amidst burning hospital buildings. Commissar Nikolai Bogateyev attempted to organize the few armed Soviet soldiers on the island, but they were quickly overwhelmed, and Bogateyev was killed in a hand-to-hand fight. After securing a foothold on the South Island, leading elements from the 130th Infantry Regiment attempted to reach the Citadel via the bridge to Kholm Gate. The Soviet 84th Rifle Regiment had its quarters in this section of the ring barracks, and Commissar Fomin organized a large group of men from various units. The Germans came under withering fire and fell back. On their heels, Fomin sent forward a detachment from his regiment, which took up positions around the South Island end of the bridge.

Rubble from collapsed buildings formed convenient fighting positions for the defenders who, moving through basements, often popped up behind advancing Germans. Early in the fighting, several light tanks and armored cars from reconnaissance battalions stationed inside the fortress bolstered the Soviet resistance before being knocked out or rendered inoperative.

The Soviet defenders maintained hopes of rescue as the sounds of a cannonade came from the east. Throughout the day, several surviving radios in the fortress broadcasted desperate calls for help that went unanswered. Group commanders sent messengers to their respective divisions’ headquarters in Brest, but they either could not reach the city or did not return. Fomin sent two armored cars, but they returned empty-handed after finding three different gates blocked by wreckage or under intense fire.

South of the fortress, German artillery swept through the lodgements of the Soviet 22nd Tank Division and artillery regiments from the 28th Rifle Corps. Especially hard hit were artillery parks, destroying not only the guns but large numbers of trucks and tractors, denying the Soviets the ability to withdraw most of the surviving pieces. Despite suffering severe losses, Col. Viktor Puganov organized an orderly retreat of his tank division, bringing almost 100 tanks to their staging areas at Zhabinka after having a brief brush with the 3rd/130th Infantry Regiment.

Northwest of Brest, German artillery and ground attack smashed through the 6th and 42nd Rifle Divisions before they had time to occupy their defensive positions. Many untrained recruits, called up in the spring of 1941 from the former Polish territories and reluctant to serve in the Red Army, used the opportunity to slip away in the confusion.

Chaos reigned in Brest as small groups of German commandos and saboteurs created an impression that the Germans entered the city in force. Soviet military and civilian authorities, rather than organizing defense, were fleeing the city in panic. Commanders of the 6th and 42nd Rifle Divisions, forgoing their men in the fortress, attempted to extricate the bulk of their divisions and withdraw to Zhabinka.

By 9 a.m., as Soviet resistance in the fortress stiffened, Maj. Gen. Schlieper realized that rapid capture of the fortress was impossible. After committing his reserve battalion, the 2nd/135th Infantry Regiment, Schlieper requested and received permission from the XII Army Corps to take back his third regiment, the 133rd Infantry. Around 11 a.m., the fresh regiment went into action but could not make headway against the Citadel. German platoons and companies became intermixed with Soviet defenders, and fighting frequently degenerated into hand-to-hand combat among burning buildings while Soviet snipers fired from every side.

In early afternoon, Schroth ordered Schlieper to pull his men back from the Citadel, where approximately 70 German soldiers from the 135th Infantry Regiment remained surrounded in the former church in the Citadel’s courtyard.

By the end of June 22, the 45th Infantry Division had suffered 313 men killed, including 10 by friendly fire. The 135th Infantry Regiment alone lost 180 killed, including two battalion commanders and one company commander. Despite the unexpected heavy losses, the day was an overall success for the 45th Infantry Division. All the bridges over the Mukhavetz and Bug rivers in its sector have been captured intact. The South Island was largely in German hands while sporadic skirmishes continued on the Western Island, and a strong position was established in the western part of the North Island. By nightfall, around 1,600 Soviet soldiers either surrendered or were taken prisoner. During the night, small groups of Soviet soldiers slipped through the still porous German encirclement.

By the end of June 22, the Commander of the 4th Army, Maj. Gen. Aleksandr Korobkov gathered and rallied his units at Zhabinka. He felt confident in holding his position until reinforcements arrived and was shocked upon receiving orders on the morning of June 23 to counterattack toward Brest. In a futile effort, Korobkov’s army was shattered by Guderian’s advancing panzers, eliminating any chance of rescuing the beleaguered defenders of Brest Fortress.

Throughout June 23, German ground attacks on the fortress alternated with heavy artillery bombardment. Between barrages, two German trucks with loudspeakers addressed the Soviet soldiers in Russian, advising them to surrender. By the end of the day, the South Island was cleared entirely. On the West Island, Soviet defenders, mainly border guards, continued hit-and-run strikes before disappearing into basements and tunnels. Determined resistance continued on the North Island, where Gavrilov organized his men into four companies around the two forts and the section of the outer embankment between them.

German artillery fire slackened during the hours of darkness, allowing Soviet defenders to comb ruined buildings for weapons, ammunition, food, and medical supplies. Lack of water was especially dire because the plumbing had been destroyed by the bombardments. Attempts to get water from the river under the watch of German machine guns and illumination flares resulted in heavy casualties. A canteen full of water could cost the lives of a dozen men. During the night, small groups of defenders attempted to escape the fortress, but the majority of them were either killed, captured, or forced to turn back.

By the end of the day, the 45th Infantry Division reported 1,900 more Soviet soldiers captured at the cost of 23 of their own men killed. During the night, Zubachev and Fomin maintained contact with separate groups in the Citadel, but defenders of the North Island remained out of touch.

Renewed fighting continued on June 24, alternating with German bombardment and surrender appeals over loudspeaker. The Germans made significant progress on the North Island, capturing the West Fort as Gavrilov’s group retreated to the East Fort. They still had weapons and ammunition, and their two anti-aircraft guns were in direct fire, and a quad machine gun kept the Germans away. With the Soviet resistance diminishing, Colonel John made another attempt with panzerjager vehicles and infantry, reaching his men trapped in the former fortress church.

German infantry attacking from the West and South Island overcame Soviet resistance near the Terespol and Kholm gates and occupied strong positions in the ring barracks. Soviet defenders under Potapov and Kizhevatov were pushed out of the Border Guard barracks and the barracks of the 333rd Rifle Regiment and joined Zubachev and Fomin in the ruins of the 33rd Engineer Regiment barracks. Fifty-two German soldiers were killed and several hundred Soviet soldiers taken prisoner.

During the night, commanders of the several groups in the Citadel met in the basement under the 33rd Engineer Regiment barracks. After the war, a frayed three-page document, titled Order #1 and dated June 24, was found under the ruins. The document, which appears to be a draft, outlined a plan to create a unified command organized into a battalion of four companies. Captain Zubachev was appointed joint force commander, with Fomin as his deputy. Although Fomin’s rank as a Regimental Commissar was equivalent to that of a lieutenant colonel, being a political officer, he formally deferred to Zubachev’s status as a line officer. However, by the strength of personality and charisma, Fomin was the group’s real leader.

Zubachev and Fomin only had direct contact with Soviet soldiers in the barracks of the 455th Rifle and 33rd Engineering Regiments. Gavrilov on the North Island and the few holdouts on the West Island remained out of contact.

Conditions in the fortress had become unbearable for the men and women taking shelter in basements and tunnels under ruined buildings. Dead bodies were everywhere and beginning to smell in the summer heat. Fires that started the first day continued to burn, with smoke and dust exacerbating the problem. Water and food were scarce, and ammunition was dwindling. Medications and bandages ran out, and wounded were dying in increasing numbers.

Knowing that the Germans maintained increased vigilance at night to prevent escapes, the council decided to break out during daylight hours the next day. For that purpose, Lieutenant Vinogradov formed a company of 120 of the most physically capable and best-armed soldiers to spearhead the breakout attempt.

On June 25, the Germans conducted minor probing attacks, preferring the artillery to reduce the pockets of resistance. Around noon, Vinogradov’s company gathered unobserved in the barracks of the 455th Rifle Regiment. Upon signal, machine gunners on the second floor opened suppressing fire on German machine gun positions across the bridge at the Three-Arch Gate. Taken by surprise, the Germans were slow to respond, allowing Vinogradov’s company to establish a small bridgehead on the North Island. Still, the attack cost Vinogradov a quarter of his men.

Once in position to cover the rest of the battalion, Vinogradov sent up a pre-arranged signal flare. A short time later, Zubachev and Fomin responded with two flares, which meant Vinogradov had to proceed alone. It is unknown why the two officers decided to remain in the fortress. It is possible they considered that the Germans were fully alerted now, and continued breakout attempts would cause too many casualties, and they wanted to wait for the night. It is also possible they did not want to abandon almost 600 wounded and civilians gathered in the basements.

On the evening of June 25, Vinogradov’s company reached the southeast corner of the North Island. Pursued by the Germans, the men broke up into several small groups. The next day, the Germans surrounded and captured a wounded Vinogradov and the last 12 men with him. He survived the POW camps and was liberated by American troops in 1945.

Between June 26 and 28, organized Soviet opposition in the Citadel largely collapsed under the relentless pounding of German artillery. German casualties dropped off as they systematically mopped up small pockets of shell-shocked and exhausted defenders. Between June 25 and June 28, 22 more German soldiers were killed, the last of them on June 27. Schlieper withdrew his 130th and 135th Infantry Regiments, which suffered the most casualties, into Brest to rest, leaving the 133rd Infantry Regiment to contain the fortress and continue mopping up operations. Matevosian, who led the bayonet charge on the first day of war, was wounded and captured, surviving the war in captivity.

On June 28, the last of Soviet women and children left the fortress. Most were taken to the Brest prison and released several weeks later. However, several families were rounded up and executed in early 1942.

A group under lieutenants Potapov and Kizhevatov held out until June 29 under the barracks of the 333rd Rifle Regiment when they made a desperate attempt to break out toward the West Island. The majority of the group was killed or captured during the attempt. Kizhevatov is believed to have been killed fighting a rear-guard action.

Groups under Zubachev and Fomin in the ruins of the 33rd Engineer Regiment barracks in the Citadel and under Gavrilov in the East Fort still refused to surrender. Every man was either wounded or sustained injuries. But more than physical pain and hunger, the men suffered from thirst. Those under the 33rd Engineer Regiment barracks dug a shallow well in the sandy soil, barely producing a canteen of water daily. The men dug a shallow well under the stables in the East Fort, but the polluted water wasn’t drinkable.

On June 29 and 30, upon request from Schlieper, Junkers Ju 88A-4s from Kampfgesch-wader 3 flew bombing sorties from a nearby Polish airfield. During the two days of air attacks, German aircraft dropped 22 500-kg bombs on the Citadel and the East Fort and one 1,800-kg bomb on the fort.

After the massive explosion at the East Fort, which shattered windows in Brest, some 380 shell-shocked Soviet defenders stumbled out of the ruins into captivity. Gavrilov and several men in ones and twos continued to evade capture.

Suffering from concussion, Zubachev and Fomin were taken prisoner on June 30. One of Fomin’s men betrayed him to the Germans for being a Commissar and a Jew, and Fomin was immediately shot near the Kholm Gate. Zubachev died in a concentration camp in 1944.

With the last pockets of resistance eliminated, the 45th Infantry Division reported the Brest Fortress taken. Between July 2 and July 6, all its units departed the vicinity of Brest to be replaced by a security battalion. While claiming to take more than 7,200 Soviet soldiers captive, the 45th Infantry Division reported 32 officers and 424 enlisted killed or dying of wounds and 31 officers and 637 enlisted wounded. It is unknown how many Soviet soldiers died in the fortress, estimates put the number over 2,000—but hundreds of corpses were buried in shell and bomb craters in the fortress courtyard.

Even after June 30, there were still diehards hiding among the fortress ruins and occasionally sniping at the German soldiers. Gavrilov, alone, emaciated and his uniform hanging in tatters, was captured on July 23.

On August 26, Adolf Hitler and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini visited the Brest Fortress on a tour of the Eastern Front. Hitler was looking forward to hosting an event at the White Palace, the former garrison church where the Peace of Brest-Litovsk was signed. To his disappointment, the building had suffered extensive damage in the fighting, rendering it unsafe and unusable for publicity photographs.

Of the thousands of Red Army POWs captured at the Brest Fortress, almost 800 survived the war. Upon returning to the Soviet Union, the former prisoners were ostracized as cowards and traitors, with many receiving prison sentences when they returned home. Gavrilov, the only surviving resistance leader, was stripped of this rank and lived in abject poverty.

Even though some of the 45th Infantry Division’s documents fell into Soviet hands during the winter of 1941/1942, the defense of the Brest Fortress remained largely unknown in the Soviet Union. Some stories circulated in the local press until, in the early 1950s, Soviet author Sergei Smirnov became passionate about telling the story of the Brest Fortress.

During several years of painstaking efforts, Smirnov located and interviewed hundreds of veterans, civilians, and family members. Through two books and multiple radio programs, the story of the heroic fortress became known to the population of the Soviet Union at large. A retired officer, Smirnov had sufficient connections and influence to rehabilitate the slighted defenders of the Brest Fortress. In 1957, Gavrilov and Kizhevatov (in his case, posthumously) received the Medal of the Hero of the Soviet Union, the country’s highest military decoration. Fomin and Zubachev posthumously received the Order of Lenin and the Order of the Patriotic War 1st Degree, respectively.

On November 8, 1956, a museum was opened on the territory of the Brest Fortress, eventually expanding to a large memorial complex complete with eternal flame and several massive statues. The imposing former St. Nicholas church has been restored, and several sections of the ring barracks remain standing. Most of the ruined buildings have been either demolished or taken apart for their bricks in reconstruction after the war. More than 26 million visitors have paid homage to the heroism of fortress defenders.

There’s an outstanding movie about this battle. Titled “The Brest Fortress”, available free on YouTube. Made in 2010 by the Russians and Belarusians. Well worth watching.