By Steven Weingartner

Although Hannibal Barca has rightly been hailed as one of history’s greatest military commanders, his reputation for greatness is based largely on his performance in the first three years (218-202 bc) of the 16-year conflict known as the Second Punic War. But his achievements in that period, while nothing short of astounding, did not produce decisive results. His superior gifts as a practitioner of military art and his brilliance as a tactician enabled Hannibal to outmarch, outmaneuver, and outfight the Romans wherever he met them. But all his achievements ultimately were to no avail. He could defeat the Roman armies; he could not defeat Rome itself. Nor did he achieve any significant success in the years that followed. After Cannae in 216 he did not fight—much less win—any major battles on Italian soil, even though he remained in Italy for the better part of 14 years. His next big battle, fought in North Africa (at Zama in 202), was also his last, and he lost it as well, thereby losing the war. Ultimately, therefore, Hannibal must be judged a great military commander who was nonetheless a great failure. Why was this so?

The answer to this question can be found in his abilities—or, rather, his lack thereof—as a strategist. Hannibal was a native of Carthage, a city-state located near modern-day Tunis. Founded in the ninth century bc by Phoenician settlers from Tyre, Carthage became a military and economic power in the western Mediterranean and, eventually, the chief rival of the region’s other ascendant power, Rome. During the second and third centuries bc, Carthage and Rome engaged in three separate conflicts collectively known as the Punic Wars (after the Latin word Poeni, or Phoenicians, which is what the Romans called the people of Carthage). The First Punic War (264-241) was fought mainly at sea and ended with Carthage relinquishing Sicily to Rome. Carthage was also vanquished in the Second Punic War (218-202), but not before Hannibal brought Rome to the brink of collapse. In the Third Punic War (149-146), the Romans finally captured Carthage and destroyed it.

Hannibal was the eldest son of Hamilcar Barca, leader of Carthage’s prominent Barcid family and the commanding admiral of the Carthaginian navy. In 237 bc, nine-year-old Hannibal accompanied his father to the Temple of Melquart, the chief Carthaginian god, and placed his hand on the sacrificial altar. Hamilcar ordered his son to swear an oath that he would never be a friend to Rome. It was a promise he would always keep. For the next several years, Hannibal learned the art of war from the ground up in his father’s camps in Iberia (Spain), where Hamilcar conducted an effective guerrilla war against the Romans’ Spanish allies. With the help of local recruits, Hamilcar established new trading centers at New Carthage (Cartagena) and Barca’s Town (Barcelona) before being killed in battle against Spanish tribesmen in 228 bc.

Hamilcar was succeeded by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal the Fair, who assumed command of the Carthaginian army in Spain, a post he held until his assassination in 221. Shortly thereafter, the army elected the 26-year-old Hannibal as its commander and, true to his temple oath, he promptly began preparing for a renewal of hostilities with Rome. A dispute soon arose over control of the Greek outpost of Saguntum in Spain, where the Romans had instigated a coup d’etat and installed a government hostile to Carthage. Hannibal subsequently invested the city, which he captured after an eight-month siege, provoking a formal declaration of war from Rome in 218. It didn’t matter to the Romans that Saguntum was south of the Ebro River, the dividing line between Roman and Carthaginian territory. They considered Hannibal an untried and untested leader, and doubted that he could mount and effective challenge to the Roman Empire. They were mistaken.

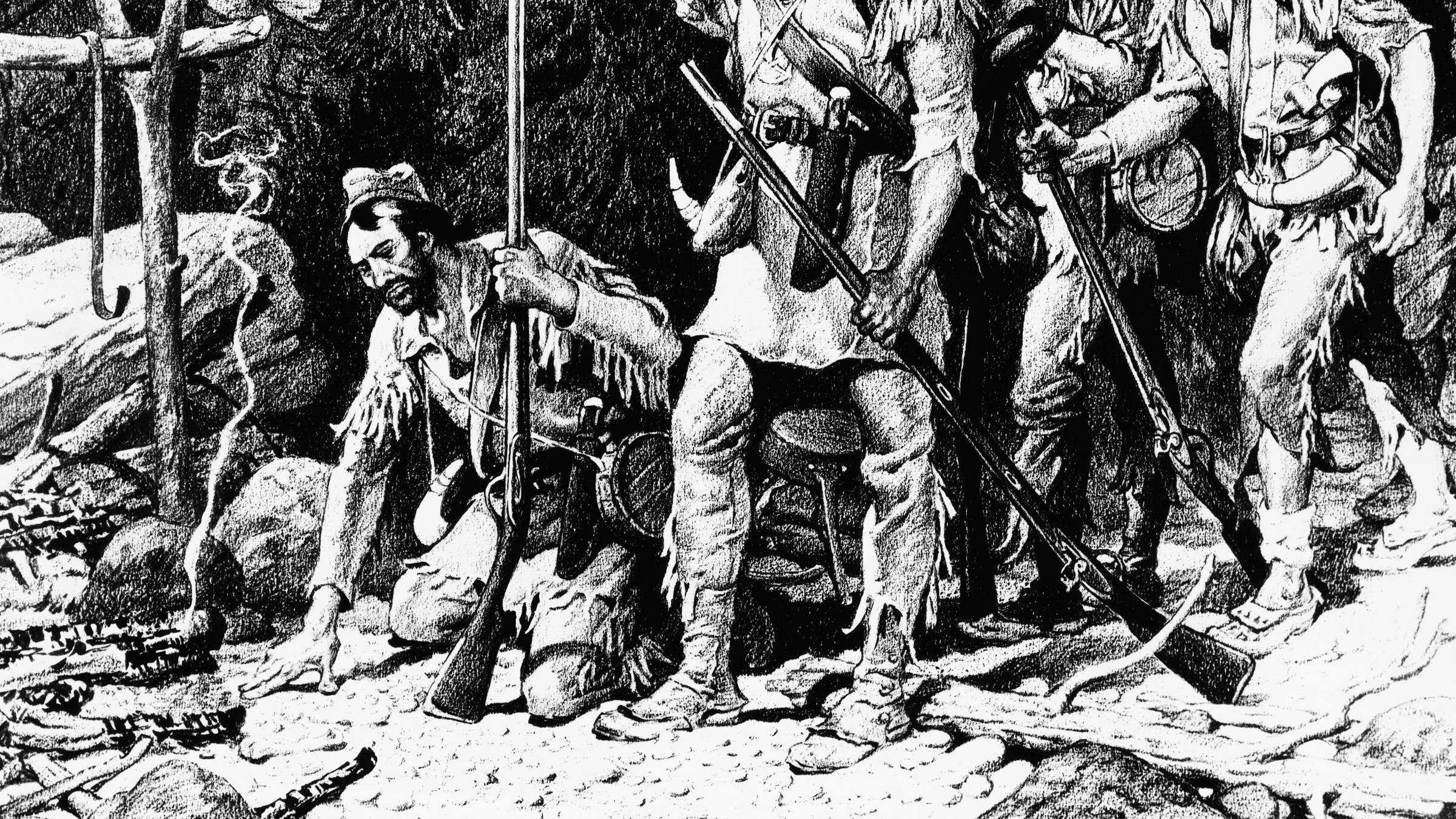

That same year, Hannibal took his army on an epic overland march across the Alps and through Gaul into northern Italy, where he hoped to exploit unrest among the Celtic tribes of the region. The Romans did not at first consider Hannibal’s invasion a serious threat, believing it was impossible for anyone to make the mountainous crossing. Hannibal proved them wrong, but not before losing nearly half his men and most of his colorful troop transports—elephants—to the wintry weather. Hannibal and his multiethnic, polyglot army, with a sizable mercenary contingent, began a 1,000-mile trek from Spain over the Pyrenees, across southern France, and finally across the Alps and down into the Po Valley. In France, at the Rhone River, he sidestepped Publius Scipio’s Roman army. Along the way, he intermittently battled local tribes. He took his army over the Alps in late autumn, after winter weather had descended on the high passes, and through it all he held his army together, which alone was a remarkable achievement.

Hannibal’s invasion of Italy was one of the great military feats of the age, at once a masterpiece of operational maneuver, a textbook case of leadership in adversity, and a triumph of mental and physical endurance. But the fact that Hannibal had to make the journey was also evidence of a profound weakness in Carthage’s war-waging capabilities—namely the lack of an effective navy to provide seaborne support for its overseas armies. The Carthaginian navy, under Hannibal’s father, had been largely destroyed in the First Punic War, and in the 23 years that followed, the city’s oligarchy had given shipbuilding priority to merchant vessels over war galleys. In the meantime, the Roman navy had grown to dominate the seas. Hannibal took the land route to Italy because Rome and Carthage’s elite left him no other choice.

Rome’s control of the western Mediterranean prevented Hannibal from receiving meaningful reinforcements from either Spain, his primary source of fighting men, or North Africa. He tried to make good his losses by recruiting among the Celtic tribes of northern Italy, and to some extent he was successful in this endeavor. However, there were never enough Celts willing to join him and always too many Italians eager to oppose him. As a result, Hannibal suffered serious manpower shortages and always fought outnumbered.

Striking at the system of alliances that Rome had built with other Italian states was the cornerstone of Hannibal’s strategic formulations. He recognized that the Italian confederation provided Rome with the vast manpower reserves and material resources it needed for a prolonged war with Carthage. It was, in modern parlance, Rome’s strategic center of gravity. If Hannibal could break the confederation, he could break Rome. It was a long shot, but the best shot he had.

Hannibal felt it was an attainable goal. He believed that many if not most of the allied states wished to be free of Roman domination and that they were only waiting for favorable circumstances to break away. He determined to create those circumstances by bringing Rome to battle early and often and by winning those battles convincingly, firm in the conviction that his own army was more than a match for any force the Romans could send against it. His victories would leave Rome too battered to retaliate against their disloyal allies, enabling them to defect to the Carthaginian cause. Eventually the defections would reach such a critical mass that Rome would be weakened beyond repair and its citizens would lose the will to continue the war. The Romans would then sue for peace, and in the negotiated settlement that would follow, the Carthaginians would impose terms that would restore Carthage to parity with Rome.

Hannibal enjoyed initial success in his war-making efforts. Once in Italy, he made good his losses suffered in the march across the Alps by persuading thousands of Celts to join his ranks. Moving south with his army, he fought a cavalry engagement at the River Ticinus. This clash was small in scale, hardly more than a skirmish, but it was important strategically as it convinced even more Celts to cast their lot with the Carthaginians.

Shortly thereafter, Hannibal smashed a Roman army at the River Trebia, killing an astonishing 30,000 of the 40,000 Roman troops deployed against him. In the spring of 217, he again exhibited his gift for operational maneuver by crossing the Apennines and passing through the Arnus marshes, interposing his army between Rome and the bulk of Roman forces that were supposed to defend it in the north. The Romans’ northern force hastened south, and Hannibal ambushed and virtually annihilated it on the shore of Lake Trasimene, killing another 30,000 legionaries.

In the aftermath of the Lake Trasimene disaster, the Roman Senate appointed Q. Fabius Maximus as temporary dictator, putting him in charge of Rome’s armies. Fabius avoided open battle with Hannibal. Instead, he implemented a strategy of mobile containment, attrition, and delay (hence his moniker, Cunctator, Latin for Delayer), whereby his forces shadowed the Carthaginian army, conducting fighting withdrawals and otherwise harrying the enemy’s rear and flanks. According to Plutarch, Fabius opposed Hannibal “not with intention to fight him, but with the purpose of wearing out and wasting the vigor of his arms by lapse of time, of meeting his want of resources by superior means, by large numbers the smallness of his forces. With this design, he always encamped on the highest grounds, where the enemy’s horse could have no access to him. Still he kept pace with them; when they marched he followed them; when they encamped he did the same, but at such a distance as not to be compelled to an engagement and always keeping upon the hills, free from the insults of their horse; by which means he gave them no rest, but kept them in a continual alarm.”

The so-called Fabian strategy prevented Hannibal from inflicting further crushing defeats on Roman armies, but it did not stop him from ravaging the countryside, and thus he was unpopular with the Romans being ravaged. In the spring of 216, after Hannibal’s army marched from its winter quarters at Gerunium, the Romans sacked Fabius, replaced him with two generals, Lucius Aemilius Paulus and Gaius Terentius Varro, who were more eager to fight,. The senate gave them a mighty army numbering around 86,000 men and a clear mandate to destroy the invaders. Instead, at the Battle of Cannae, near the Adriatic Coast, Hannibal maneuvered his outnumbered forces to execute a double envelopment of the Roman army. The result was a catastrophe for the Romans. In several hours of ferocious combat, the force caught in the envelopment, numbering about 45,000 legionaries, was virtually annihilated.

Hannibal did not follow up on his victory by marching on Rome. According to the Roman historian Livy, he paused for a day and a night to allow his troops, exhausted by the effort required to slaughter so many Romans, to rest. Marhabal, the Carthaginian cavalry commander, had urged Hannibal to seize the moment and attack the capital. When Hannibal refused, Marhabal reproached his commander: “You know how to win victory, Hannibal, you do not know how to use it.” It was a complaint repeated many centuries later by Confederate cavalry leader Nathan Bedford Forrest, who wondered why General Braxton Bragg had not followed up his stunning victory at Chickamauga by immediately capturing Chattanooga. “What does he fight battles for?” Forrest wondered.

Marhabal’s criticism was both unfair and erroneous. Hannibal surely knew how to “use” victory. But Hannibal also knew that moving on Rome would entail a lengthy siege, and his army had no siege equipment. Nor did it have enough men to garrison its conquests in Italy while investing the Eternal City. A naval task force from Carthage or Spain might have delivered both the men and equipment Hannibal needed. But the Carthaginian navy was virtually defunct, and Rome ruled the sea. In any event, Hannibal did not attack Rome directly. Instead, he continued to pursue his previous strategic course, hoping that Cannae would induce more of Rome’s allies to come over to the Carthaginian cause. A number of allied states, notably Capua and Tarentum, did indeed defect, but overall the alliance held and Rome and its citizens remained stalwart in their prosecution of the war.

Fabius Maximus was restored to command of Roman forces in Italy and, as before, continued to avoid open battle: “Fabius adhered to his former principles,” wrote Plutarch, “still persuaded that, by following close and not fighting him, Hannibal and his army would at last be tired out and consumed, like a wrestler in too high condition, whose very excess of strength makes him the more likely suddenly to give way and lose it.”

Eventually, Hannibal and his army proved Plutarch right. They remained bogged down in southern Italy, an irritant but not a threat to Rome, for the next 14 years. Meanwhile, the Romans, content with containing Hannibal in the south, focused their efforts on the conquest of Spain. It was clear to Hannibal that his grand strategy had failed, and in 202 he returned to North Africa, there to preside over Carthage’s downfall. Later that year, he was defeated by Roman general Publius Cornelius Scipio at the Battle of Zama, and Carthage sued for peace shortly thereafter. Hannibal spent his final years living in exile in Bithynia, eventually committing suicide at age 64 upon learning that Roman agents were seeking his arrest. “It is time now to end the great anxiety of the Romans who have grown weary of waiting for the death of a hated old man,” he said, drinking poisoned wine.

If it is true, as Appian says, that Hannibal ranked Alexander the Great and Pyrrhus of Epirus as the world’s first and second greatest generals (he ranked himself third), then it is safe to say that they had a major influence on his development and performance as a general, which was only to be expected: Hannibal was a man of his times, and in his time all soldiers looked up to Alexander and Pyrrhus as military paragons. Hannibal was no different, and the imprint of their thinking is clearly discernible in his generalship and battle craft. All three men lived in an age when heavy infantry was an army’s primary combat arm, its arm of decision. Cavalry, while important, was used principally in a supporting role, as a facilitator for the main event, the clash of opposing infantry formations. To that end, mounted formations would literally shape the battlefield for the infantry by sweeping in from the wings and conducting exploitation and pursuit operations. Cavalry was not used in shock charges against infantry because the infantry of the time was too strong and was generally capable of withstanding and beating any and all cavalry attacks.

Hannibal worked within a tactical framework that had been around in some form or other since the development of cavalry in the early centuries of the first millennium bc. He was also circumscribed by the emerging technology of edged-weapon warfare. He saw no need to alter it. His brilliance, at least as a tactician, was his ability to adapt his army to the circumstances of the battlefield and to create a battlefield that was suitable to his army. He was a master of manipulating prebattle events so that when battle was finally joined, it was on ground that maximized his army’s strengths and minimized its weaknesses. Later generations of military theorists would call this talent “coup d’oeil.” Coined by Frederick the Great, the Prussian king who spoke French as his language of choice, the term translates literally as “eye to the ground.” Prussian military planner Karl von Clausewitz defined it as a quality of intellect, possessed by superior generals, which “even in the darkest hour retains some glimmerings of the inner light which leads to truth” and that enables them to identify the “relationship between warfare and terrain” and use it to their advantage. More simply put, Hannibal, like other great commanders, had “guts.” He didn’t panic in the extremely fluid conditions of battle. He could keep his head, as Rudyard Kipling would say, while others around him were losing theirs—sometimes literally.

That said, it is revealing that Hannibal should have held Pyrrhus, in particular, in such high esteem. Like Hannibal, Pyrrhus fought and won numerous battles against the Romans—and, also like Hannibal, he eventually lost his war with Rome. As Robert E. Lee would discover in the U.S. Civil War, winning battles did not always translate into winning wars. Indeed, the two endeavors were sometimes at cross purposes. While Lee was fighting and winning battles—at least until Gettysburg—his great Union counterpart, Ulysses S. Grant, was devising a different strategy. Grant proposed, with deceptive simplicity, to attack Lee simultaneously and on all fronts, keeping him off balance with unremitting pressure. President Abraham Lincoln assured Grant that he would have all the men he needed for the job, which amounted to the simple arithmetic of subtraction, one by one, of Lee’s dwindling defenders. When enough Confederates had been subtracted, the North would win. That was Grant’s plan. It worked beautifully—except for the thousands of soldiers, Union and Confederate, who were subtracted by it.

The Battle of Cannae was Hannibal’s crowning achievement. In the modern age, it has mesmerized military theorists and commanders, who regard his tactic of double envelopment as a textbook example of how to fight and win decisively on the battlefield against a numerically superior force. The Germans were particularly taken with the perceived efficacy of fighting a “battle of annihilation” (Vernichtungsschlacht) as a means of solving their perennial problem of waging war on multiple fronts. Writing in On War, Clausewitz asserted that the goal of land war was to destroy the enemy army. In the late 19th century, Count Alfred von Schlieffen, chief of the German general staff, became convinced that Cannae provided the perfect model for destruction, a conclusion he reached after reading Hans Delbrück’s account of the battle. Schlieffen himself penned a treatise on the subject, Cannae, calling it “the perfect battle,” and commissioned the historical section of the general staff to produce a series of essays known as Cannae Studies that analyzed and extolled the virtues of the annihilating encirclement battle.

Somehow it escaped Schlieffen’s notice that a strategy predicated on winning battles decisively did not necessarily produce a quick, decisive victory in war. Hannibal’s experience should have been instructive in the same way that his victory at Cannae had been inspirational, but Schlieffen and his many disciples managed to ignore it—at their own peril. The form of battle became more important than the aim. Victory and battle became one and the same, and the technique of fighting a battle became all important. The Cannae concept would have a profound influence on German operational and strategic planning in both World War I and World War II and would be directly responsible for the development of blitzkrieg style of warfare that the Wehrmacht used repeatedly and with great success in the first three years of World War II.

The battle-centric approach to warfare, with its Cannae-style battle of annihilation as its centerpiece, was not without its critics. Of these, the most prolific and articulate was Friedrich von Bernhardi, a German general and military theorist. Bernhardi was particularly critical of Schlieffen’s belief that the encirclement battle of annihilation should become every army commander’s overweening goal in every battle, to the exclusion of other methods, including penetration and breakthrough tactics.

In the opening round of World War I, Germany attempted to deliver a knockout blow against France with a vast turning movement (or single envelopment) conducted by enormous armies attacking through Belgium into northern France and then wheeling south toward Paris. The German scheme of maneuver was based on Schlieffen’s Cannae-inspired formulations and bore his name, but the “Schlieffen Plan” failed to produce the decisive victory envisioned by its creator. Defeated almost miraculously at the Battle of the Marne in September 1914, the Germans found themselves without a winning strategy, much less the means to implement it, and the long war of attrition that ensued in the freezing trenches of the Western Front led inevitably to Germany’s defeat in November 1918.

In World War II, both Germany and Japan proved adept, like Hannibal, at winning battles, only to lose the war. Especially notable are the battles that the Wehrmacht won in summer 1941 as part of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia. In the course of Barbarossa, the German army executed the greatest encirclement and annihilation battles of all time: for example, in the encirclement battles at Minsk and Smolensk (mid-July), Kiev (August 21-September 26), and Vyazma (September 30-October 7) the Germans bagged over 1.7 million prisoners, to say nothing of the millions of Soviet soldiers killed in those battles. Nonetheless, the Wehrmacht failed to capture Moscow and Leningrad, its key strategic goals, and by early December the Red Army launched a massive counteroffensive that came within in ace of destroying the Wehrmacht outright and left it permanently weakened for the rest of the war.

Similarly, the forces of Japan quickly overran much of Asia and the Pacific, but the victories in China, Singapore, Burma, and the Philippines—most infamously at Corregidor—overstretched Japanese supply lines and enabled the United States and its allies to hold steady, then roll back Japanese advances. The Japanese sneak attack at Pearl Harbor, intended to put the U.S. Navy completely out the war, narrowly failed to do so, and the subsequent U.S. naval victories at the Coral Sea and Midway paved the way for the bloody but decisive island-hopping campaign by U.S. Marines and soldiers across the Pacific. Like Hannibal, the Japanese learned the hard way about the loss of sea power to a determined and resourceful enemy.

Perhaps the most trenchant commentary on the pitfalls of the battle-centric strategy was delivered by a North Vietnamese colonel named Tu in a conversation with U.S. Army Colonel Harry Summers during the Summer’s 1974 trip to Hanoi to discuss the status of U.S. prisoners of war. Summers told Tu, “You know, you never beat us on the battlefield.” To which Tu replied, “That may be so, but it is also irrelevant.” Less than a year later, in April 1975, North Vietnamese tanks rolled through Saigon, and the war in which U.S. forces had lost no major battles ended in total victory for North Vietnam. Hannibal would have understood.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments