By Patrick J. Chaisson

It didn’t take long for Rear Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., to notice how exhausted the men all seemed. Newly appointed as Commander, South Pacific Area, Halsey had just arrived on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands to inspect conditions there. The date was November 8, 1942.

At the airfield, First Marine Division Commander Maj. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift enthusiastically welcomed his high-ranking guest to CACTUS (code name for Guadalcanal). Vandegrift’s 20,000 soldiers, sailors, and Leathernecks had been steadfastly holding this strategic lodgment against relentless Japanese attacks for three months now. The strain of near-constant combat was beginning to tell on them, though, as Halsey observed during a jeep tour of the front lines.

An aide described how the admiral “talked with a large number of Marines, saw their gaunt, malaria-ridden bodies, their faces lined with what seemed a nightmare of years” that day. After dark, “Bull” Halsey experienced for himself this living nightmare endured by every American on Guadalcanal.

It began when an enemy destroyer entered Ironbottom Sound and traded shellfire with Marine artillery batteries on shore, forcing the visiting admiral into an air raid shelter. Later, the sound of unsynchronized aircraft engines high overhead again sent CACTUS defenders diving back into their bunkers.

“Washing Machine Charlie,” a two-engined bomber, had announced its presence. For several hours this nocturnal pest circled around just beyond the range of American antiaircraft guns, occasionally dropping a flare or anti-personnel bomb. It was a harassment tactic designed to keep those manning the perimeter awake, scared, and miserable.

The raid robbed Halsey of any rest that night. In his postwar autobiography, he blamed this on fright, not the noise itself. He repeatedly told himself, “‘Go to sleep, you damned coward!’ but it didn’t do any good; I couldn’t obey orders.”

Admiral Halsey flew out of Guadalcanal after sunrise, but the memory of his unsettled night there remained fresh. Some weeks later, he wrote Maj. Gen. Ross E. Rowell, commander of Marine Aircraft Wings Pacific, with a proposed remedy to nocturnal irritants like Washing Machine Charlie.

“Current night nuisance raids over CACTUS are lowering combat efficiency of our troops through loss of sleep and increased exposure to malaria during hours of darkness spent in foxholes and dugouts,” Halsey claimed. “Recommend that minimum of six night fighting aircraft with homing radars … plus ground equipment be dispatched CACTUS earliest time.”

Rowell forwarded the admiral’s request to Marine Corps Commandant Lt. Gen. Thomas Holcomb in Washington for an answer. It then became Holcomb’s duty to inform Halsey of an embarrassing fact: The USMC could not send six radar-equipped interceptor aircraft to Guadalcanal. In fact, one year into the Pacific War, his Marines did not yet possess a single operational night fighter.

“In the beginning,” recounted U.S. Marine Corps historians, “there were no planes, no pilots, no American precedents, very little recognition of the need for night fighters, and extremely primitive equipment for locating enemy planes.” Clearly, the Leathernecks would need help if they ever hoped to intercept hostile aircraft during the hours of darkness.

By 1941, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) had made great strides toward perfecting an early-warning system that employed radio waves to determine the distance, direction, and speed of approaching warplanes. This so-called “radar” (an acronym for “radio detection and ranging”) played a crucial, even decisive, role in the Battle of Britain fought that previous summer.

To counter the threat from nocturnal bombers, British scientists rapidly developed an ingenious microwave radar that could be mounted inside a high-performance aircraft. Night fighters could now be precisely guided toward a target by ground control intercept (GCI) stations, then utilize their own short-range aircraft interception (AI) systems to close in for the kill. For some time, the RAF had been employing radar-fitted Boulton Paul Defiants in this role with modest success.

In November 1941, USMC Major Frank H. Schwable received orders assigning him as a Special Military Observer to the United Kingdom. Schwable, 33, was a 1929 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy who went on to earn his aviator’s wings shortly thereafter. His prewar assignments included service as a Marine pilot in Nicaragua, as well as duty with the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics.

Before leaving for England, Schwable was instructed “to get all the information you can on the organization and operations of [RAF] night fighting squadrons, paying particular attention to the operational routine, squadron training, gunnery, and tactical doctrine.” He spent three and a half months there, even attending the fighter director school at Stanmore, until a new assignment brought him home the following spring.

While Major Schwable was overseas, much preliminary work on the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps night fighter program had begun. Permission was granted to license-build AI and GCI radars in the United States; these sets were designated the SCR-540 and SCR-527A, respectively. And in March 1942, Commandant Holcomb directed that a total of eight 12-plane USMC night fighter squadrons be activated— but the first of these squadrons was not scheduled to take wing until January 1, 1945.

Evidently, the Marine Corps brass did not consider night fighter operations a high priority. That summer, however, freshly promoted Lt. Col. Schwable helped convince headquarters to push the activation of these squadrons forward by three years. Thus, on July 25, 1942, Marine Night Fighter Squadron VMF(N)-531 was authorized, with Schwable named as its first commanding officer. The unit would organize and train at Cherry Point Marine Air Station, then being constructed out of a North Carolina swamp.

“We started with nothing,” Frank Schwable would recall later. “In fact, we were the first combat squadron to move into one of the new hangars down there.” Conditions at Cherry Point were so austere that Schwable’s office, tucked into the corner of an unheated shed, was furnished solely with “three packing boxes. That was our desk and that was our chair.”

New personnel arrived steadily. Among the first men to report aboard were Majors John D. Harshberger and Robert O. Bisson. Harshberger, an early convert to night fighter operations, served as second-in-command. Bisson, although a rated aviator, took charge of VMF(N)-531’s GCI detachment. Harshberger and Bisson were soon promoted to Lt. Col., an unusual arrangement that reflected both the organization’s large size and its highly technical, specialized mission (a typical USMC fighter squadron rated one major as commanding officer). This was anything but a typical outfit, as the “Grey Ghosts” (their squadron nickname) were learning.

Frank Schwable, meanwhile, struggled to find an aircraft his squadron could take to war. Not ready yet were purpose-built night fighters like the Northrop P-61 Black Widow, a warplane that was already plagued by numerous design problems and wouldn’t become operational until late 1944. Single-seat Navy interceptors such as the Vought F4U-2 Corsair and Grumman F6F-3E/N Hellcat, fitted with AI radar, were set to reach the fleet possibly as early as mid-1943, but that still wasn’t soon enough. Someone (possibly Schwable) even suggested the British send over a dozen radar-equipped Bristol Beaufighters in a reverse Lend Lease exchange.

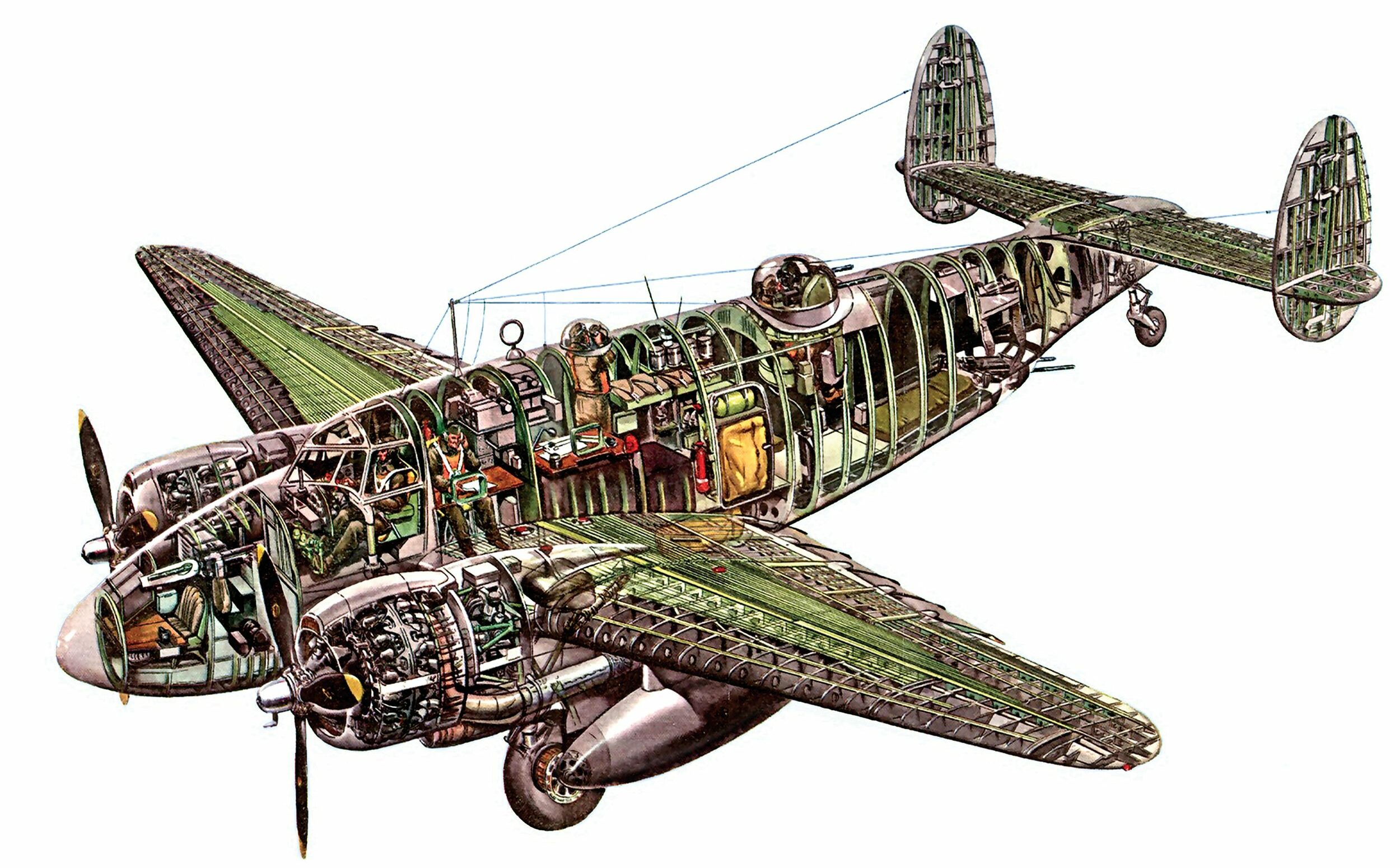

The U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics (in charge of supplying aircraft to the Marine Corps) finally settled on a highly modified version of the Lockheed-Vega PV-1 Ventura patrol bomber for this requirement. Twin-engined and with a usual crew of three (pilot, radar operator, and top turret gunner), the Ventura stood at the top of a short list of airplanes that could carry aloft the bulky SCR-540 air interception radar set. It would take months to make all the necessary conversions on VMF(N)-531’s 12 PV-1s, though, and flight crews needed immediate practice in nighttime navigation, takeoff, and landing.

In October the Grey Ghosts acquired two North American SNJ-4 and one Curtiss SNC-1 trainer aircraft, but they required additional planes to accommodate the squadron’s growing flock of newly assigned Marine aviators—most of whom had come straight from flight school at Pensacola, Florida. Several Brewster SB2A-4 Buccaneer scout-bombers, “repossessed” from a Royal Netherlands Air Force contract, came to the squadron in December. These Brewsters caused a great deal of trouble, to put it mildly.

First, the Brewsters’ instrument panel placards were all written in Dutch. Their propellers’ electrical contacts frequently burned out, and the main landing gear struts often collapsed on landing. Over the span of 14 days, one SB2A-4 experienced a hydraulic failure, another shed its tail-wheel locking pin, one more had its control stick lock up, and a fourth plane snapped both rudder cables—all while in flight. Schwable grounded the defective Brewsters until his mechanics could perform a thorough overhaul on each aircraft.

Flying “blind” (i.e., totally reliant on instruments) was a skill every night fighter pilot had to master. Marine Corps aviators did receive basic instruction in all-weather navigation at Pensacola, but more training was needed. A reservist named Major Karl S. Day ran an intensive “attitude instrument flight school” at Fort Worth, Texas, using Douglas R4D-3 Skytrain transports. The Grey Ghosts attended Day’s course, afterward gaining new confidence in their ability to aviate without being able to see anything outside the cockpit.

Meanwhile, VMF(N)-531’s ground controllers learned the intricate business of guiding (“vectoring,”as they called it) a fighter aircraft toward an interception point from which the flight crew could then take over with its short-range radar. Getting that night fighter to an ideal interception point meant putting it 600 feet astern and slightly below its prey on the same course and speed; no easy task, given the temperamental electronics then in use. It demanded constant practice; whenever weather conditions permitted, the Grey Ghosts were up in their undependable Brewsters, following GCI’s vectors to locate a target plane flying somewhere in the darkness.

Throughout the spring of 1943, VMF(N)-531 trained, organized, and received the equipment it needed to fight. Yet the squadron’s PV-1 Venturas, delayed by difficulties with the conversion process, still had not arrived at Cherry Point. Those aircraft were scattered all up and down the East Coast, traveling first to a depot

in Norfolk, Virginia, where six nose-mounted .50-caliber machine guns and a gunsight were installed in each plane. They then went to Quonset Point, Rhode Island, to be fitted with SCR-540 radar and Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) transponders. These top-secret electronic interrogators communicated with ground and ship-based stations, allowing controllers to know the location of all the planes in the chaos of combat.

But installing all this equipment took time. By June 2, the Grey Ghosts had on hand just three Lockheeds—none of which worked properly. Pilots complained of a poorly placed gunsight mount that blocked their view of the altimeter and that also vibrated loose in flight. Radar sets frequently malfunctioned, while oxygen and electrical systems also proved unreliable. Every day, it seemed, another problem arose with VMF(N)-531’s Venturas that had to be fixed before the squadron could ship out. In no way was the squadron going to make its projected overseas movement date of July 15, 1943.

Frank Schwable kept his superiors informed of these disappointing developments in a series of technical reports: “45 to 55 minutes to climb to 20,000 feet,” he wrote of the PV-1s’ inferior performance at altitude. “Very little maneuverability…above 15,000 feet. Very slow acceleration in level flight above 10,000 feet.”

In all official correspondence, Lieutenant Colonel Schwable characterized the Lockheed as a “makeshift” night fighter. Yet his personal notes, written while en route to Hawaii, reveal the squadron commander’s doubts about this deeply flawed warplane his Leathernecks would fly into battle: “It is only if the Japs are more stupid than anybody thinks they are and come down to 15,000 ft. do we even stand a chance to knock them down—if we can go fast enough to catch them! If we lack speed expert vectoring may put us in a position to do some good, but if the Japs fly thousands of feet higher than our planes can physically be pushed up to, there’s not one damned thing on God’s green earth we can do about it.”

The Grey Ghosts resigned themselves to doing what they could with what they had. Continuing troubles with the hastily modified Venturas obliged them to deploy in three groups beginning on August 1. Six PV-1s and their flight crews set sail from San Diego aboard the escort carrier USS Long Island, while other vessels carried into the South Pacific VMF(N)-531’s ground echelon and its GCI detachment. All remaining air crewmen would follow along once their fighters became operational.

Toward the end of August, Schwable and Harshberger arrived on Guadalcanal and learned their squadron now fell under the command of Marine Air Group 21 (MAG-21). The two officers also saw for themselves just how much had changed there in the nine months since Admiral Halsey sent up his request for night fighter support. A detachment of Army Air Forces Douglas P-70s now guarded this major Allied staging base against nocturnal prowlers, while six radar-equipped U.S. Navy F4U-2 Corsairs from VF(N)-75 were due in any day at a forward airstrip on Vella Lavella, 250 miles to the northwest.

American, Australian, and New Zealand forces had seized a number of strategic islands during their relentless march up the Solomons chain toward the massive Japanese base cluster at Rabaul, New Britain. Some objectives, such as Munda on the island of New Georgia, required an invasion force to clear out enemy defenders before construction engineers could build landing fields and supply depots. Other stepping stones on the way to Fortress Rabaul —Vella Lavella and the Russell Islands—had not been occupied by Japanese troops and were quickly transformed into Allied outposts.

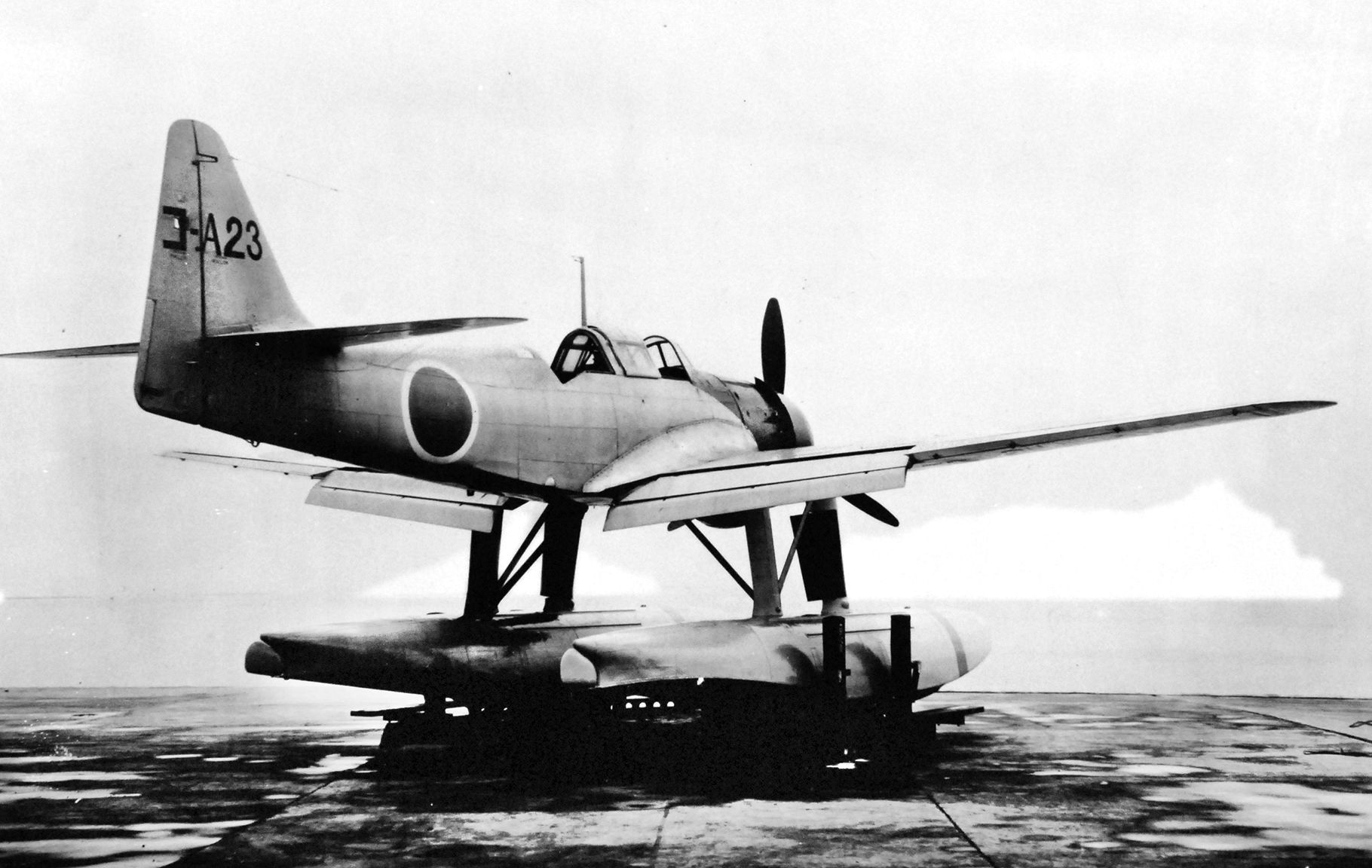

Admiral Halsey now focused his attention on the island of Bougainville in the northern Solomons. Landings at Cape Torokina were set for November 1, but the invasion fleet remained vulnerable to enemy night intruders—especially fast, well-armed Mitsubishi G4M1 “Betty” bomber aircraft flying out of Rabaul. Large numbers of Aichi E13A “Jake” floatplanes also posed a nocturnal threat to unarmored American transport ships.

To help counter this menace, the Grey Ghosts deployed to Banika airfield in the Russell Island group beginning on September 11, 1943. There, mechanics began stripping their Lockheeds of de-icing equipment, cabin heaters, and armor plate in an attempt to increase high-altitude performance. This highly irregular weight control program lightened each Ventura by as much as 1,000 pounds, resulting in noticeably improved airspeed and rate of climb.

Schwable flew VMF(N)-531’s initial night patrol on September 16. That date also marked the squadron’s first battle loss, which occurred when Lieutenant John E. Mason, S/Sgt. Ralph W. Emerson, and Corporal John J. Burkett disappeared while on a routine patrol near Guadalcanal. An extensive air search turned up no sign of the missing PV-1.

Throughout September and October, flight crews completed 47 sorties and made 17 interceptions of Japanese aircraft over Bougainville without scoring one kill. This dismal start to combat operations was due chiefly to inexperience, lack of proper ground control, and poor maintenance.

Stuck at the end of a long supply chain, VMF(N)-531 was—to make matters worse— the sole Marine Corps unit equipped with PV-1 aircraft. Often, the only way to obtain repair parts was to beg or barter for them from neighboring Ventura-equipped Royal Australian or New Zealand Air Force squadrons. Replacement radar components had to be wheedled out of U.S. Army stocks on Guadalcanal. Maintenance personnel faced an unending and largely unrecognized struggle to keep their planes flying and radars functioning.

In the meantime, Lieutenant Colonel Bisson’s ground control intercept technicians had been detached from the squadron and were operating in support of the Bougainville invasion from Pakoi Bay on the northwestern end of Vella Lavella. On October 31, Marine controllers Major Thomas E. Hicks and S/Sgt. Eugene J. Gleason directed U.S. Navy Lieutenant Hugh D. O’Neil of VF(N)-75 up against a marauding G4M1 Betty. This was the first air-to-air victory by a radar-equipped night fighter of the Pacific Fleet.

The Grey Ghosts got on the scoreboard at 0418 hours on November 14, when a Ventura named Coral Princess was coached onto an enemy plane by destroyer-based fighter directors. The PV-1’s radar operator, T/Sgt. Charles H. Stout, made initial contact with the target (a G4M1 Betty from 702 Kokutai based on Rabaul) at a range of 6,000 feet. Maneuvering in for the kill, pilot Captain Duane R. Jenkins and top-turret gunner Sergeant Thomas J. Glennon then fired three bursts that sent their prey into a fiery death dive about 50 miles southwest of Bougainville.

Tragically, Jenkins, Stout, and Glennon were lost in action three weeks later. On December 3, Coral Princess and her crew rushed in to aid a friendly convoy under attack by 15 to 25 Japanese bombers and torpedo planes. Shipboard observers saw at least one bogey (likely a Betty belonging to 751 Kokutai) fall in flames to Jenkins’ guns before all radio and radar contact with his Ventura ceased. No trace of the aviators or their Lockheed was ever found.

An all-Marine interception took place shortly after midnight on December 6, when GCI controller Captain Owen M. Hines brought Squadron Executive Officer Lt. Col. Harshberger’s PV-1 (named Gertie the Goon) behind a twin-float “Jake” from the Buka-based 938 Kokutai over Bougainville. In the Ventura with Harshberger were radio operator T/Sgt. James S. Kinne and gunner S/Sgt. Walter E. Tiedeman, as well as a co-pilot, 1st Lt. Wilbur E. Birdsall. Approaching within 800 feet of the bogey, pilot and gunner simultaneously fired a burst of .50-caliber rounds that instantly set it ablaze. Witnesses on the ground later confirmed this aerial victory.

Starting in December, the Grey Ghosts began flying frequent “night harassment” missions armed with 100- or 500-pound bombs. Targets included enemy camps beyond Allied lines at Bougainville, as well as resupply barges sailing back and forth from the nearby Shortland Islands. Harshberger, an especially pugnacious warrior, enjoyed these raids, while Schwable preferred to employ his PV-1s as night fighters. The cerebral Schwable and fiery “Iron John” Harshberger made a good team, though, together establishing a command climate dedicated in equal part to technical precision and aggressive action.

Three more Lockheeds and their flight crews arrived at Banika in mid-December, helping to take on the burden of three-to-five nightly patrols and harassment raids. Typically, the squadron commander and his executive officer each flew twice a night, in addition to their administrative responsibilities. Training newly arrived aircrewmen also took up a considerable amount of Lt. Col. Schwable’s time.

After almost four months in combat, the Grey Ghosts’ leader had flown well over 100 hours without a single kill to his credit. That all changed on the evening of January 12, 1944, when Schwable, radio operator S/Sgt. Robert I. Ward, and gunner Sergeant William T. Fletcher took their PV-1 (named Chloe) out over Bougainville’s Empress Augusta Bay.

Their first two contacts that night disappeared into a cloud bank, but at 2156 hours ground controller Captain Thompson S. Baker vectored the Ventura’s crew onto a third bogey, 12 miles away and heading northwest. Five minutes later, Ward acquired the target on his scope. It was a Nakajima B5N “Kate” torpedo bomber from the carrier Zuikaku’s air group, which Schwable and Fletcher sighted visually at a range of 3,000 feet. Closing to within 500 feet of the Kate before opening fire, their point-blank barrage ignited its fuel tank. Schwable, banking hard to avoid the explosion, remembered feeling “a scorching heat as [my] right wing cleared the flaming mass.”

This interception illustrated how well-trained ground controllers and flight crews working together could locate, approach, and destroy enemy intruders. But poorly disciplined U.S. Navy gunners often interfered with the Grey Ghosts’ missions. Marine officers could rarely convince their naval counterparts that, for all the morale-building effects of shipboard antiaircraft gunfire, these pyrotechnic displays knocked down far fewer Japanese bombers than the night fighters. Frank Schwable remembered that he “got shot at oftener by friends than by the enemy.”

On January 30, the last of VMF(N)-531’s Lockheeds arrived in theater. With the GCI detachment now set up on a new base in the Treasury Islands, the squadron’s air echelon moved forward to Barakoma airfield, on Vella Lavella. PV-1s began operations from Barakoma two days later.

Frank Schwable scored again on the night of February 5-6, when Army controllers steered Chloe into position behind a Betty bomber belonging to the 751st Kokutai flying high over Dampier Strait. Pushing the Ventura to its maximum combat ceiling of 15,000 feet, Schwable and his gunner riddled their target with three bursts of .50-caliber gunfire. The Betty then “fell off into a vertical spin,” and wreckage and an oil slick were found the next day to confirm their aerial victory.

The squadron suffered a major loss on February 9, when the PV-1 carrying 1st Lt. Clifford W. Watson, S/Sgt. Jack H. Shirk, and Sergeant George E. Brogna crashed on takeoff during heavy weather at Barakoma. There were no survivors.

Later that same night, Lieutenant Colonel Harshberger and the crew of Gertie the Goon encountered a dangerous enemy over Empress Augusta Bay. Vectored onto a bogey at 0329 hours, Harshberger urged his worn-out Lockheed up to the target’s reported altitude of 15,000 feet. At a range of two miles, radar operator T/Sgt. Kinne acquired the enemy aircraft on his scope and guided them in for an attack.

As Harshberger’s Ventura neared its quarry, Kinne saw his radar image split into two “blips.” This meant there were a pair of Japanese planes out there, something the top turret gunner quickly confirmed. Sergeant Tiedemann identified them as two Bettys in tight formation, only 2,000 feet ahead.

As Harshberger approached, both bombers opened fire on him with their 20mm tail cannon. Enemy fire disabled five of his six nose guns, as well as knocking out a radio set mounted just behind the pilot’s head. His gunner engaged the two aircraft, putting “one burst into the tail gunner of the ‘Betty’ on the right [which then peeled off right out of range],” as an aircraft action report detailed. Tiedemann “then swung back on the bogey to the left and [fired] three bursts.” The Betty (from 751 Kokutai) “started to glow internally” and took on the appearance of a brightly lit sieve before nosing into a fatal dive.

Returning to Barakoma nearly out of fuel and without radio communications, Gertie the Goon’s crew endured a friendly antiaircraft barrage before managing to land safely. Harshberger summed up the mission thusly: “Never had so much fun in my life!”

For the Grey Ghosts, February was turning out to be an especially eventful month. On the 15th, Lt. Col. Schwable and crew downed a Jake, followed two nights later by another one (both floatplanes belonged to the 938 Kokutai). This marked Frank Schwable’s fourth and final kill; after 269 combat hours and 72 missions, his time as squadron commander was over. On February 18, 1944, “Iron John” Harshberger took charge of VMF(N)-531.

The new commanding officer certainly led by example, bringing down a Jake over Bougainville on February 19. That same night, however, 1st Lt. Thaddeus M. Banks, S/Sgt. Burnell C. Bowers, and Sergeant Gilbert Jones went missing in action during a low-level barge-hunting sortie. After sunrise, search aircraft identified fragments of their Lockheed floating in the Solomon Sea.

While the Grey Ghosts kept up a busy schedule of patrols and harassment raids, the foe now seemed reluctant to send aircraft out after dark. Apart from one Jake shot down by 1st Lt. Jack M. Plunkett, S/Sgt. Floyd M. Pulham, and S/Sgt. Michael J. Cipkala on February 19, there had been no interceptions over Bougainville for nearly a month.

Harshberger, staging out of an airstrip on Torokina, scored his final victory of the war on March 14. Together with Kinne and Tiedemann in Gertie the Goon, “Iron John” made a head-on pass against a twin-float seaplane they misidentified as an Aichi E16A1 “Paul.” Postwar records indicate this was in fact another Jake from 938 Kokutai, which immediately disintegrated under their guns.

The squadron’s war diary recorded a great tragedy on March 21. “Lts. Pierce and Birdsall…flew formation towards Vella Lavella [when] about 0630 Lt. Pierce’s wing clipped Lt. Birdsall’s wing,” it read. “Pierce’s PV-1 burst into flames. Lt. Birdsall’s plane went into a spin.” Both aircraft crashed into the sea, witnesses stated, leaving eight crewmen dead.

VMF(N)-531’s time in the South Pacific was nearing its end. The squadron made no hostile contacts throughout the month of April, while newly arriving Navy and Marine outfits flying faster, more capable Hellcats or Corsairs took on an increasing number of night patrol missions. On May 6, Lt. Col. Harshberger turned over command of the Grey Ghosts to Captain James H. Wehmer and headed home.

Iron John’s record of achievement included four confirmed kills, along with an amazing 756 combat hours accrued over 100 missions. Harshberger and Schwable, pioneers of Marine Corps night fighter operations, each received the Distinguished Flying Cross for their exploits over Bougainville.

The squadron did achieve one last air-to-air victory, however. On May 11, pilot 1st Lt. Marvin E. Notestine, radar operator Sergeant Edward H. Benintende, and gunner Corporal Walter M. Kinn chased an unwary Jake into Rabaul’s Simpson Harbor, blasting their target out of the sky as it prepared to make a water landing. This, VMF(N)-531’s 12th kill, was the only one made without radar guidance.

The Grey Ghosts flew their final mission over Rabaul on July 14 and then undertook a lengthy trip Stateside. The squadron was disbanded at Cherry Point that September, but did not remain dormant for long. On October 13, 1944, VMF(N)-531 reactivated with orders moving it to Marine Corps Air Station Eagle Mountain Lake, Texas. There it would become the first USMC unit to field Grumman’s F7F Tigercat night fighter.

Japan surrendered before the Grey Ghosts could take their hot new interceptors into battle, but VMF(N)-531’s record of service in World War II remains a remarkable one. At the cost of six PV-1 Venturas and 20 crewmen lost in action, the squadron received credit for one dozen aerial victories during its 10-month tour of duty over the northern Solomons.

All this had been achieved while operating a warplane that, in Lt. Col. Schwable’s opinion, was “entirely unsatisfactory as a night fighter.” Yet his men made the best of their antiquated equipment. The Grey Ghosts of the Solomons demonstrated how Marine flight crews and ground controllers working closely together could protect amphibious forces afloat and ashore during the hours of darkness. Never again would Washing Machine Charlie fly unchallenged in South Pacific skies.

Author Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired U.S. Army officer who writes on a variety of historical topics from Scotia, New York.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments